Does Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Represent a Poly-Herpesvirus Post-Virus Infectious Disease?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Are the Symptoms of a Subset of Patients with ME/CSF the Result of a Post-Virus Infection?

3. If ME/CFS Is Triggered by a Virus in Some Cases, Why Has It Not Been Identified? Factors to Consider

3.1. Lack of Standardized Criteria to Designate Individuals as Healthy Controls

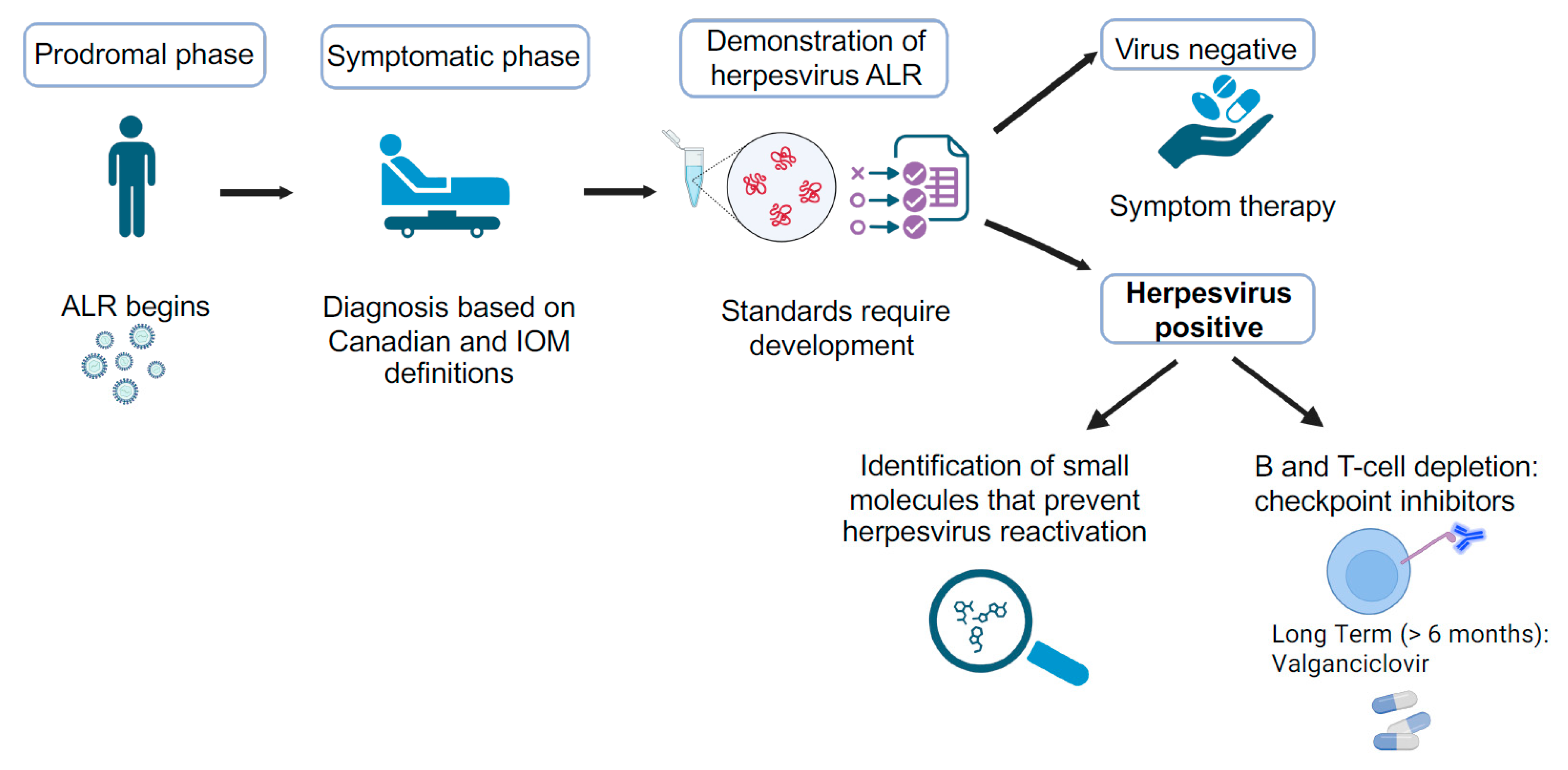

3.2. Serological Studies

3.3. Use of Viral Load as a Requirement to Demonstrate a Viral Infection

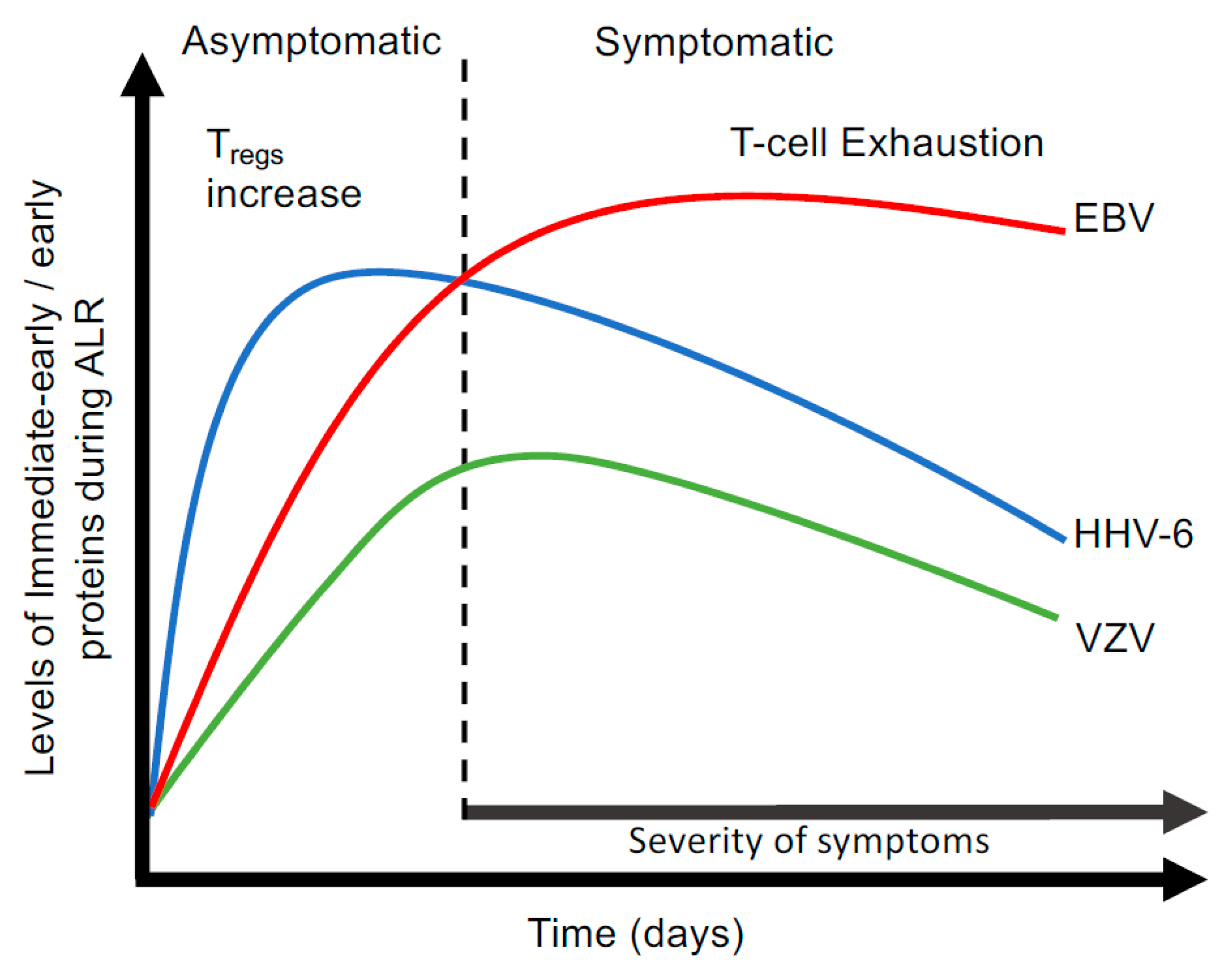

3.4. Abortive Lytic Replication (ALR)

4. Is ME/CFS the Outcome of Synergistic Interactions Between Multiple Herpesviruses?

5. Could Other Multisystem Illnesses Such as Gulf War Illness (GWI) and Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) Be Poly-Herpesvirus Infections?

5.1. Gulf War Illness (GWI)

5.2. Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC)

6. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Missailidis, D.; Annesley, S.J.; Fisher, P.R. Pathological Mechanisms Underlying Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Diagnostics 2019, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.; Maes, M. Mitochondria and immunity in chronic fatigue syndrome. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 103, 109976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatomi, Y.; Mizuno, K.; Ishii, A.; Wada, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Tazawa, S.; Onoe, K.; Fukuda, S.; Kawabe, J.; Takahashi, M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: An 11C-(R)-PK11195 PET Study. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, K.J.; Scheibenbogen, C. Pathophysiology of skeletal muscle disturbances in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, K.J.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Paul, F. An attempt to explain the neurological symptoms of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.J.; Ahn, Y.C.; Jang, E.S.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, S.H.; Son, C.G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME). J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-309-31689-7. [Google Scholar]

- Brimmer, D.J.; Jones, J.F.; Boneva, R.; Campbell, C.; Lin, J.S.; Unger, E.R. Assessment of ME/CFS (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome): A Case study for health care providers. MedEdPORTAL 2016, 12, 10527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedberg, F.; Sunnquist, M.; Nacul, L. Rethinking the standard of care for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 906–909. [Google Scholar]

- Araja, D.; Berkis, U.; Lunga, A.; Murovska, M. Shadow burden of undiagnosed Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) on society: Retrospective and prospective-in light of COVID-19. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirin, A.A.; Dimmock, M.E.; Jason, L.A. Updated ME/CFS prevalence estimates reflecting post-COVID increases and associated economic costs and funding implications. Fatigue Biomed. Health Behav. 2022, 10, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pheby, D.F.H.; Araja, D.; Berkis, U.; Brenna, E.; Cullinan, J.; de Korwin, J.D.; Gitto, L.; Hughes, D.A.; Hunter, R.M.; Trepel, D.; et al. The Role of prevention in reducing the economic impact of ME/CFS in Europe: A report from the socioeconomics working group of the European Network on ME/CFS (EUROMENE). Medicina 2021, 57, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, L.; Reeves, W.C. Factors influencing the diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 2241–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardaman, M.; Gilmour, S. Letter: Time to correct the record on the global burden of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 25, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, A.M. Myalgic encephalomyelitis, or what. Lancet 1988, 2, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, B.M. The Nightingale, Mylagic Encephalomyelitis (ME) Definition; Nightingale Research Foundation: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, B.M.; Jain, A.K.; DeMeirleir, K.L.; Peterson, D.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Lerner, A.M.; Bested, A.C.; Flor-Henry, P.; Joshi, P.; Powles, A.C.P.; et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols. J. Chronic Fatigue Syndr. 2003, 11, 7–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, G.P.; Kaplan, J.E.; Gantz, N.M.; Komaroff, A.L.; Schonberger, L.B.; Straus, S.E.; Jones, J.F.; Dubois, R.E.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Pahwa, S.; et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome: A working case definition. Ann. Intern. Med. 1988, 108, 387–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, M.C. A report-chronic fatigue syndrome: Guidelines for research. J. R. Soc. Med. 1991, 84, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitani, T.; Kuratsune, H.; Yamaguchi, K. Diagnostic criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome by the CFS study group in Japan. Nippon. Rinsho Jpn. J. Clin. Med. 1992, 50, 2600–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, K.; Straus, S.E.; Hickie, I.; Sharpe, M.C.; Dobbins, J.G.; Komaroff, A.; Schluederberg, A.; Jones, J.F.; Lloyd, A.R.; Wessely, S.; et al. The chronic fatigue syndrome: A comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, W.C.; Wagner, D.; Nisenbaum, R.; Jones, J.F.; Gurbaxani, B.; Solomon, L.; Papanicolaou, D.A.; Unger, E.R.; Vernon, S.D.; Heim, C. Chronic fatigue syndrome—A clinically empirical approach to its definition and study. BMC Med. 2005, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, B.M.; van de Sande, M.I.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Broderick, G.; Staines, D.; Powles, A.C.P.; Speight, N.; Vallings, R.; Bateman, L.; et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 270, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todhunter-Brown, A.; Campbell, P.; Broderick, C.; Cowie, J.; Davis, B.; Fenton, C.; Markham, S.; Sellers, C.; Thomson, K. Recent research in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: An evidence map. Health Technol. Assess. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason, L.A.; Najar, N.; Porter, N.; Reh, C. Evaluating the centers for disease control’s empirical chronic fatigue syndrome case definition. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2009, 20, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason, L.A.; Fox, P.A.; Gleason, K.D. The importance of a research definition. Fatigue Biomed. Health Behav. 2018, 6, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Acheson, E.D. The clinical syndrome variously called beign malgic encephalomyelitis, Iceland disease and epidemic neuromyasthenia. Am. J. Med. 1959, 26, 569–595. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neal, A.J.; Hanson, M.R. The enterovirus theory of disease in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A critical review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 688486. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, M.R. The viral origin of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 18, e1011523. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, H.; Sundal, E.; Myhr, K.M.; Nyland, H.I. Postinfectious and chronic fatigue syndromes: Clinical experience from a tertiary-referral centre in Norway. In Vivo 2010, 24, 185–188. [Google Scholar]

- Choutka, J.; Jansari, V.; Hornig, M.; Iwasaki, A. Unexplained post-acute infection syndromes. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jason, L.A.; Yoo, S.; Bhatia, S. Patient preceptions of infectious illness preceeding Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Chronic Illn. 2022, 18, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Melchers, W.; Zoll, J.; van Kuppeveld, F.; Swanink, C.; Galama, J. There is no evidence for persistent enterovirus infections in chronic medical conditions in humans. Rev. Med. Virol. 1994, 4, 235–243. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, P.; Archard, L.C. There is evidence for persistent enterovirus infections in chronic medical conditions in humans. Rev. Med. Virol. 1994, 4, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Tracy, S.; Tapprich, W.; Bailey, J.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, K.; Barry, W.H.; Chapman, N.M. 5′-Terminal deletions occur in coxsackievirus B3 during replication in murine hearts and cardic myocyte cultures and correlate with encapsidation of negative-stranded viral RNA. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 7024–7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, C.T.; Kimura, T.; Frimpong-Boateng, K.; Whitton, J.L. Immunological and pathological consequences of coxsackievirus RNA persistence in the heart. Virology 2017, 512, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, N.M. Persistent enterovirus infection: Little deletions, long infections. Vaccines 2022, 10, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasa, S.; Nora-Krukle, Z.; Henning, N.; Eliassen, E.; Shikova, E.; Harrer, T.; Schelibenbogen, C.; Murovska, M.; Prusty, B.K. Chronic viral infections in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, J.; Chia, A.; Voeller, M.; Lee, T.; Chang, R. Acute enterovirus infection followed by myalgic encephalomeyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Clin. Pathol. 2010, 63, 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.H.; Lee, J.S.; Oh, H.M.; Lee, E.J.; Lim, E.J.; Son, C.G. Evaluation of viral infection as an etiology of ME/CFS: A systemic review and meta-analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 763. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, N.E.; Straus, S.E. Chronic fatigue syndrome and herpesviruses: The fading evidence. Herpes 2000, 7, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Howley, P.M.; Knipe, D.M.; Cohen, J.L.; Damania, B.A. Fields Virology: DNA Viruses, 7th ed.; Wolters Kluwer Publishers: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 979-1-9751-1257-8. [Google Scholar]

- Maple, P.A.C.; Hosseini, A.A. Human alpha herpesviruses infections (HSV1, HSV2, and VZV), Alzheimer’s disease, and the potential benefits of targeted treatment or vaccination—A virological perspective. Vaccines 2025, 13, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Li, X. Human cytomegalovirus: Pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Mol. Biomed. 2024, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agut, H.; Bonnafous, P.; Gautheret-Dejean, A. Laboratory and clinical aspects of human herpesvirus 6 infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, R.; Vandekerckhove, L.; Van Cleemput, J. Update on human herpesvirus 7 pathogenesis and clinical aspects as a roadmap for future research. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0043724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Robertson, E.S. Epstein–Barr virus history and pathogenesis. Viruses 2023, 15, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigney, J.; Zhang, K.; Greas, M.; Liu, Y. A review of KSHV/HHV8-associated neoplasms and related lymphoproliferative lesions. Lymphatics 2025, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.H.; Lin, S.C.; Hsu, Y.H.; Chen, S.Y. The human virome: Viral metagenomics, relations with human diseases and therapeutic applications. Viruses 2022, 14, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholamzad, A.; Khakpour, N.; Hashemi, S.M.A.; Goudarzi, Y.; Ahmadi, P.; Gholamazad, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Hashemi, M. Exploring the virome: An integral part of human health and disease. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2024, 260, 155466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.R.; Uyaguari-Diaz, M.; McCabe, M.N.; Montoya, V.; Gardy, J.L.; Parker, S.; Steiner, T.; Hsiao, W.; Nesbitt, M.J.; Tang, P.; et al. Metagenomic investigation of plasma in individuals with ME/CFS highlights the importance of technical controls to elucidate contamination and batch effects. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giloteaux, L.; Hanson, M.R.; Keller, B.A. A pair of identical twins discordant for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome differ in physiological parameters and gut microbiome composition. Am. J. Case Rep. 2016, 10, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouquet, J.; Gardy, J.L.; Brown, S.; Pfeil, J.; Miller, R.R.; Morshed, M.; Avina-Zubieta, A.; Shojania, K.; McCabe, M.; Parker, S.; et al. RNA-seq analysis of gene expression, viral pathogen and B-cell/T-cell receptor signatures in complex chronic disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 64, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouquet, J.; Li, T.; Gardy, J.L.; Kang, X.; Stevens, S.; Stevens, J.; VanNess, M.; Snell, C.; Potts, J.; Miller, R.R.; et al. Whole blood human transcriptome and virome analysis of ME/CFS patients experiencing post-exertional malaise following cardiopulmonary exercise testing. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.Y.; Savva, G.M.; Telatin, A.; Tiwari, S.K.; Tariq, M.A.; Newberry, F.; Seton, K.A.; Booth, C.; Bansal, A.S.; Wileman, T.; et al. Investigating the human intestinal DNA virome and predicting disease-associated virus-host interactions in severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briese, T.; Tokarz, R.; Bateman, L.; Che, X.; Guo, C.; Jain, K.; Kapoor, V.; Levine, S.; Hornig, M.; Oleynik, A.; et al. A multicenter virome analysis of blood, feces and saliva in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obraitis, D.; Li, D. Blood virome research in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): Challenges and opportunities. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2024, 68–69, 101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walitt, B.; Singh, K.; LaMunion, S.R.; Hallett, M.; Jacobson, S.; Chen, K.; Yoshimi Enose-Akahata, Y.; Apps, R.; Barb, J.J.; Bedard, P.; et al. Deep phenotyping of post-infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, V.C.; Greene, K.A.; Tabachnikova, A.; Bhattacharjee, B.; Sjogren, P.; Bertilson, B.; Reifert, J.; Zhang, M.; Kamath, K.; Shon, J.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid immune phenotyping reveals distinct immunotypes of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Immunol. 2025, 15, vkaf087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vider-Shalit, T.; Fishbain, V.; Raffaeli, S.; Louzoun, Y. Phase-dependent immune evasion of herpesviruses. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 9536–9545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loebel, M.; Eckey, M.; Sotzny, F.; Hahn, E.; Bauer, S.; Grabowski, P.; Zerweck, J.; Holenya, P.; Hanitsch, L.G.; Wittke, K.; et al. Serological profiling of EBV immune response in chronic fatigue syndrome using a peptide microarray. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomberg, J.; Rizwan, M.; Bohlin-Wiener, A.; Elfaitouri, A.; Julin, P.; Zachrisson, O.; Rosen, A.; Gottfries, C.G. Antibodies to human herpesviruses in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paschale, M.; Clerici, P. Serological diagnosis of Epstein-Barr virus infection: Problems and solutions. World J. Virol. 2012, 12, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, N.V.V.; Lehtonen, J.; Veijola, R.; Lempainen, J.; Knip, M.; Hyoty, H.; Laitin, O.H.; Hytonen, V.P. Multiplex high-throughput serological assay for human enteroviruses. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertens, T.; Pika, U.; Eggers, H.J. Cross antigenicity among enteroviruses as revealed by immunoblot technique. Virology 1983, 129, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuelson, A.; Forsgren, M.; Johansson, B.; Wahren, B.; Sallberg, M. Molecular basis for serological cross-reactivity between enteroviruses. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 1994, 1, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, J.; Smith, W.A.; Stone, S.R.; Thomas, W.R.; Hales, B.J. Species-specific and cross-reactive IgG1 antibody binding to viral capsid protein 1 (VP1) antigens of human rhinovirus species A, B and C. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70552. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.J.; Kula, T.; Xu, Q.; Li, M.Z.; Vernon, S.D.; Ndung’u, T.; Ruxrungtham, K.; Sanchez, J.; Brander, C.; Chung, R.T.; et al. Comprehensive serological profiling of human populations using a synthetic human virome. Science 2015, 348, aaa0698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopegamage, S. Enterovirus infections: Pivoting role of the adaptive immune response. Virulence 2016, 7, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, N.V.V.; Stone, V.M.; Hankaniemi, M.M.; Mazur, M.A.; Vuorinen, T.; Flodström-Tullberg, M.; Hyöty, H.; Hytönen, V.P.; Laitinen, O.H. Antibody responses against enterovirus proteases are potential markers for an acute infection. Viruses 2020, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouppila, N.V.V.; Lehtonen, J.; Seppälä, E.; Puustinen, L.; Oikarinen, S.; Laitinen, O.H.; Knip, M.; Hyöty, H.; Hytönen, V.P. Assessment of enterovirus antibodies during early childhood using a multiplex immunoassay. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0535222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, B.; Flamand, L.; Juwana, H.; Middeldrop, J.; Naing, Z.; Rawlinson, W.; Ablashi, D.; Lloyd, A. Serological and virological investigation of the role of the herpesviruses EBV, CMV and HHV-6 in post-infective fatigue syndrome. J. Med. Virol. 2010, 82, 1684–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Swanink, C.M.; van der Meer, J.W.; Vancoulen, J.H.; Bleijenberg, G.; Fennis, J.F.; Galama, J.M. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and the chronic fatigue syndrome: Normal virus load in blood and normal immunological reactivity in the EBV regression assay. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 20, 1390–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebel, M.; Strohschein, K.; Giannini, C.; Koelsch, U.; Bauer, S.; Doebis, C.; Thomas, S.; Unterwalder, N.; von Baehr, V.; Reinke, P.; et al. Deficient EBV-specific B-and T-cell response in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristianse, M.S.; Stabursvik, J.; O’Leary, E.C.; Pedersen, M.; Asprusten, T.T.; Leegaard, T.; Osnes, L.T.; Tjade, T.; Skovlund, E.; Godang, K.; et al. Clinical symptoms and markers of disease mechanisms in adolescent chronic fatigue following Epstein-Barr virus infections: An exploratory cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 80, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laichalk, L.L.; Thorley-Lawson, D.A. Terminal differentiation into plasma cells initiates the replicative cycle of Epstein-Barr virus in vivo. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 1296–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Tabaa, Y.; Tuaillon, E.; Bollore, K.; Foulongne, V.; Petitjean, G.; Seigneurin, J.M.; Duperray, C.; Desgranges, C.; Vendrell, J.P. Functional Epstein-Barr virus reservoir in plasma cells derived from infected blood memory B cells. Blood 2009, 113, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Tabaa, Y.; Tuaillon, E.; Jeziorski, E.; Ouedraogo, D.E.; Bollore, K.; Rubbo, P.A.; Foulongne, V.; Rodiere, M.; Vendrell, J.P. B-cell polyclonal activation and Epstein-Barr viral abortive lytic cycle are two key features in acute infectious mononucleosis. J. Clin. Virol. 2011, 52, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altmann, M.; Hammerschmidt, W. Epstein-Barr virus provides a new paradigm: A requirement for the immediate inhibition of apoptosis. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Iwakiri, D.; Yamamoto, K.; Maruo, S.; Kanda, T.; Takada, K. Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 gene, a switch from latency to lytic replication, is expressed as an immediate-early gene after primary infection of B lymphocytes. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon-Lowe, C.; Adland, E.; Bell, A.I.; Delecluse, H.J.; Rickman, A.B.; Rowe, M. Features distinguishing Epstein-Barr virus infections of epithelial cells and B cells: Viral genome expression, genome maintenance, and genome amplification. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 7749–7760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalla, M.; Hammerschmidt, W. Human B cells on their route to latent infection-early but transient expression of lytic genes of Epstein-Barr virus. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 91, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, L. Characterizing cytomegalovirus infection one cell at a time. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 1477–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, M.Y.; Weissman, J.S. Functional single-cell genomics of human cytomegalovirus infection. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prusty, B.K.; Gulve, N.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Schuster, M.; Strempel, S.; Descamps, V.; Rudel, T. HHV-6 encoded small non-coding RNAs define an immediate and early stage in viral replication. Genom. Med. 2018, 3, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, B.A.; Harth-Hertle, M.L.; Malterer, G.; Haas, J.; Ellwart, J.; Schulz, T.F.; Kempkes, B. Abortive lytic reactivation of KSHV in CBF1/CSL deficient human cell lines. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003336. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.M.; Rappocciolo, G.; Jenkins, F.J.; Rinaldo, C.R. Dendritic cells: Key players in human herpesvirus 8 infection and pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneja, K.K.; Yuan, Y. Reactivation and lytic replication of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: An update. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.Z.; Russell, T.A.; Spelman, T.; Carbone, F.R.; Tscharke, D.C. Lytic replication is frequent in HSV-1 latent infection and correlates with the engagement of a cell-intrinsic transcriptional response. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drayman, N.; Patel, P.; Vistain, L.; Tay, S. HSV-1 single cell analysis reveals the activtion of anti-viral and developmental programs in distinct sub-populations. eLife 2019, 8, e46339. [Google Scholar]

- Kobiler, O.; Afriat, A. The fate of incoming HSV-1 genomes entering the nucleus. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 41, 221–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrikson, J.P.; Domanico, L.F.; Pratt, S.L.; Loveday, E.K.; Taylor, M.P.; Chang, C.B. Single-cell herpes simplex virus type 1 infection of neyrons usingdrop-based microfluidics reveals heterogeneous replication kinetics. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk9185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laemmie, L.; Goldstein, R.S.; Kinchington, P.R. Modeling Varicella zoster virus persistence and reactivation-closer to resolving a perplexing persistent state. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1634. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, B.E.; Yee, M.B.; Zhang, M.; Hornung, R.S.; Kaufer, B.B.; Visalli, R.J.; Kramer, P.R.; Goins, W.F.; Kinchington, P.R. Varicella-zoster virus early infection but not complete replication is required for the induction of chronic hypersensitivity in rat models of postherpatic neuralgia. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009689. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Bruckner, N.; Weissmann, S.; Gunther, T.; Zhu, S.; Vogt, C.; Sun, G.; Guo, R.; Bruno, R.; Ritter, B.; et al. Repression of varicella zoster gene express during quiescent infection in the absence of detectable histone deposition. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1012367. [Google Scholar]

- Halpin, P.; Williams, M.V.; Klimas, N.G.; Fletcher, M.A.; Barnes, Z.; Ariza, M.E. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and gulf war illness patients exhibit increase humoral responses to the herpesviruses-encoded dUTPase: Implications in disease pathophysiology. J. Med. Virol. 2017, 89, 1637–1645. [Google Scholar]

- Mena Paloma, I.; Cox, B.; Williams, M.V.; Ariza, M.E. Chronic reactivation of persistent human herpesviruses and hightened anti-dUTPase IgG antibodies is a recurrent hallmark in infectious ME/CFS and is associated with fatigue. J. Med. Virol. 2025. accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Kasimir, F.; Toomey, D.; Liu, Z.; Kaiping, A.C.; Ariza, M.E.; Prusty, B.P. Tissue specific signature of HHV-6 infection in ME/CFS. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1044964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.M.; Zervos, M.; Dworkin, H.J.; Chang, C.H.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Goldstein, J.; Lawrie-Hoppen, C.; Franklin, B.; Krotkin, S.M.; Brodsky, M.; et al. New cardiomyopathy: Pilot study of intravenous ganciclovir in a subset of the chronic fatigue syndrome. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 1997, 6, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, A.M.; Zervos, M.; Dworkin, H.J.; Chang, C.H.; O’Neill, W. A unified theory of the cause of chronic fatigue syndrome. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 1997, 6, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manian, F.A. Simultaneous measurement of antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 ad 14 enteroviruses in chronic fatigue syndrome: Is there evidence of activation of a nonspecific polyclonal immune response? Clin. Infect. Dis. 1994, 19, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapenko, S.; Krumina, A.; Logina, I.; Rasa, S.; Chistjakovs, M.; Sultanova, A.; Viksna, L.; Murovska, M. Association of active human herpesvirus-6,-7 and parvovirus B19 infection with clinical outcomes in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Adv. Virol. 2012, 2012, 205085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasa-Dzelzkaleja, S.; Krumina, A.; Capenko, S.; Nora-Krukle, Z.; Gravelsina, S.; Vilmane, A.; Ievina, L.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Murovska, M.; on behalf of the VirA project. The persistent viral infections in the development and severity of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliff, J.M.; King, E.C.; Lee, J.S.; Sepulveda, N.; Wolf, A.S.; Kingdon, C.; Bowman, E.; Dockrell, H.M.; Nacul, L.; Lacerda, E.; et al. Cellular immune function in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, T.D.; Grabowska, A.D.; Lee, J.S.; Ameijerias-Alonso, J.; Westermeier, F.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Cliff, J.M.; Nacul, L.; Lacerda, E.M.; Mourino, H.; et al. Herpesvirus serology distinguishes different subgroups of patients from the United Kingdom myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome biobank. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 686736. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, A.M.; Beqaj, S.H.; Deeter, R.G.; Dworkin, H.J.; Zervos, M.; Chang, C.H.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Goldstein, J.; O’Neill, W. A six-month trial of valacyclovir in the Epstein-Barr virus subset of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Improvement in left ventricular function. Drugs Today 2002, 38, 549–561. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, A.M.; Beqaj, S.H.; Deeter, R.G.; Fitzgerald, J.T. Valacyclovir treatment in Epstein-Barr virus subset chronic fatigue syndrome; thirty-six months follow-up. In Vivo 2007, 21, 707–714. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, A.M.; Beqaj, S.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Gill, K.; Gill, C.; Edington, J. Subset-directed antiviral treatment of 142 herpesvirus patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Virus Adapt. Treat. 2010, 2, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kogelnik, A.M.; Loomis, K.; Hoegh-Petersen, M.; Rosso, F.; Hischier, C.; Montoya, J.G. Use of valganciclovir in patients with elevated antibody titers against human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) who were experiencing central nervous system dysfunction including long-standing fatigue. J. Clin. Virol. 2006, 73, S33–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt, T.; Oberfoell, S.; Balise, R.; Lunn, M.R.; Kar, A.K.; Merrihew, L.; Bhangoo, M.S.; Montoya, J.G. Response to valganciclovir in chronic fatigue syndrome patients with human herpesvirus 6 and Epstein-Barr virus IgG antibody titers. J. Med. Virol. 2012, 84, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Montoya, J.G.; Kogelnik, A.M.; Bhangoo, M.; Lunn, M.R.; Flamand, L.; Merrihew, L.E.; Watt, T.; Kubo, J.T.; Paik, J.; Desai, M. Randomized clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of valganciclovir in a subset of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Med. Virol. 2013, 85, 2101–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, J.M.; Edwards, J.M.; Fletcher, W.; McSwiggan, D.A.; Pereira, M.S. Measurement of heterophile antibody and antibodies to EB viral capsid antigen IgG and IgM in suspected cases of infectious mononucleosis. J. Clin. Pathol. 1976, 29, 841–847. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, B.Z.; Shiraishi, Y.; Mears, C.J.; Binns, H.J.; Taylor, R. Chronic fatigue syndrome after infectious mononucleosis in adolescents. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, B.Z.; Jason, L.A. Chronic fatigue syndrome following infections in adolescents. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2013, 25, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason, L.A.; Katz, B.; Gleason, K.; McManimen, S.; Sunnquist, M.; Thrope, T. A prospective study of infectious mononucleosis in college students. Int. J. Psychiatry 2017, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central]

- Katz, B.Z.; Reuter, C.; Lupovitch, Y.; Gleason, K.; McClellan, D.; Cotler, J.; Jason, L.A. A validated scale for assessing the severity of acute infectious mononucleosis. J. Pediatr. 2019, 209, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason, L.A.; Cotler, J.; Islam, M.F.; Sunnquist, M.; Katz, B.Z. Risk for developing Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome in college students following infectious mononucleosis: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e3740–e3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason, L.A.; Katz, B.Z. Predisposing and precipitating factors in Epstein-Barr. Virus-caused Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemon, S.M.; Hutt, L.M.; Blum, J.; Pagano, J.S. Simultaneous infection with multiple herpesviruses. Am. J. Med. 1979, 66, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, G.; Dreiner, N.; Krueger, G.R.; Ramon, A.; Ablashi, D.V.; Salahuddin, S.Z.; Balachandram, N. Frequent double infection with Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus-6 in patients with acute infectious mononucleosis. In Vivo 1991, 5, 271–279. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.; Huntington, M.K. Co-infection with cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus in mononucleosis: Case report and review of literature. S. D. Med. 2009, 62, 351–353. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yang, K.; Wei, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, D. Coinfection with EBV/CMV and other respiratory agents in children with suspected infectious mononucleosis. Virol. J. 2010, 7, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ameen, O.; Mohammed, A.; Faisal, M.; Kohla, S.; Abdulhadi, A. Co-infection of cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus in an immunocompetent patient: A case series and literature review. Cureus 2023, 15, e47599. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle, A.J.; Turkova, A.; Cunnington, A.J. When do co-infections matter? Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 31, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.; Khan, A.; Chattopathy, P.; Mehta, P.; Sahni, S.; Sharma, S.; Pandey, R. Co-infections as modulators of disease outcome: Minor players or major players? Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 664386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y. Viral coinfections. Viruses 2022, 14, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhou, H.Y.; Zheng, H.; Wu, A. Towards understanding and identification of human viral co-infections. Viruses 2024, 16, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamand, L.; Stefanescu, I.; Ablashi, D.V.; Menezes, J. Activation of the Epstein-Barr Virus replicative cycle by human herpesvirus 6. J Virol. 1993, 67, 6768–6777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karner, W.; Bauer, G. Activation of a Varicella-zoster virus specific IgA response during acute Epstein-Barr virus infection. J. Med. Virol. 1994, 44, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitksrsnts, A.; Piiparinen, H.; Mannonen, L.; Vesaluoma, M.; Vaheri, A. Detection of human herpesvirus 6 and varicella-zoster virus in tear fluid of patients with Bell’s palsy by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 2753–2755. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Li, T.; Zeng, M.; Peng, T. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection activates the Epstein-Barr virus replication cycle via a CREB-dependent mechanism. Cell. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 546–559. [Google Scholar]

- Hama, N.; Abe, R.; Gibson, A.; Phillips, E.J. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS)/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): Clinical features and pathogenesis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizukawa, Y.; Shiohara, T. Recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of DIHS/DRESS in 2025. Allergol. Int. 2025, 74, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kano, Y.; Hiraharas, K.; Sakuma, K.; Shiohara, T. Several herpesviruses can reactivate in severe drug-induced multiorgan reaction in the same sequential order as in graft-versus-host disease. Br. J. Dermatol. 2006, 155, 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Seishima, M.; Yamanaka, S.; Fuijsawa, T.; Tohyama, M.; Hashimoto, K. Reactivation of human herpesvirus (HHV) family members other than HHV-6 in drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Br. J. Dermatol. 2006, 155, 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, G.A.; Ripa, M.; Burastero, S.; Benanti, G.; Bagnasco, D.; Nannipieri, S.; Monardo, R.; Ponta, G.; Asperti, C.; Cilona, M.B.; et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): Focus on the pathophysiological and diagnostic role of viruses. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukawa, Y.; Aoyama, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Takahashi, R.; Shiohara, T. Risk of progression to autoimmune disease in severe drug eruption: Risk factors and the factor-guided stratification. J. Investig. Dermatol 2022, 142, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Usherwood, E.J. Immune escape of γ-herpesviruses from adaptive immunity. Rev. Med. Virol. 2014, 24, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Geng, S.; Suo, Y.; Wei, X.; Cal, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhou, X.; Shi, Y. Critical role of regulatory T cells in the latency and stress-induced reactivation of HSV-1. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 2379–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Q.; Cuo, X.; Luo, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhong, L.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y.; Zeng, X.; Feng, Z. Dynamic immune landscape and VZV-specific T cell responses in patients with herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 887892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakh, M.K.; Doroudchi, M.; Talepoor, V.A. Induction of regulatory T cells after virus infection and vaccination. Immunology 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.; Brenu, E.; Broadley, S.; Kwiatek, R.; Ng, J.; Nguyen, T.; Freeman, S.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Regulatory T, natural killer T and γδ T cells in multiple sclerosis and chronic fatigue syndrome/Myalgic encephalomyelitis: A comparison. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 34, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, J.L.; Palencia, T.; Fernandez, G.; Garcia, M. Association of T and NK cell phenotype with the diagnosis of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, H.; Sato, W.; Yamamura, T. Dysregulation of T and B cells in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 381, 899–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.; Hoag, G.E.; Salerno, J.P.; Horning, M.; Klimas, N.; Selin, L.K. Identification of CD8 T-cell dysfunction associated with symptoms in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and Long COVID and treatment with a nebulized antioxidant/anti-pathogen agent in a retrospective case series. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 36, 100720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton-Fitch, N.; Rudd, P.; Er, T.; Hool, L.; Herrero, L.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Immune ehaustion in ME/CFS and Long COVID. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e183810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iu, D.S.; Maya, J.; Vu, L.T.; Fogarty, E.A.; McNairn, A.J.; Ahmed, F.; Franconi, C.J.; Munn, P.R.; Grenier, J.K.; Hanson, M.R.; et al. Transcriptional reprogramming primes CD8+ T cells toward exhaustion in Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e241511912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.V.; Cox, B.; Ariza, M.E. Herpesviruses-encoded dUTPases: A new family of Pathogen-Associated Molecular Pattern (PAMP) proteins with Implications in human disease. Pathogens 2016, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariza, M.E.; Williams, M.V. EBV-dUTPase modulates host immune responses potentially altering the tumor microenvironment in EBV-associated maligancies. J. Curr. Res. HIV/AIDS 2016, 2016, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Young, N.A.; Williams, M.V.; Jarjour, W.N.; Bruss, M.S.; Bolon, B.; Parikh, S.; Satoskar, A.; Ariza, M.E. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) encoded dUTPase exacerbates the immune pathology of lupus nephritis in vivo. Int. J. Immunol. Immunother. 2016, 3, 023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.; McCausland, M.; Sidney, J.; Duh, F.M.; Rouphael, N.; Mehta, A.; Mulligan, M.; Carrington, M.; Wieland, A.; Sullivan, N.L.; et al. Broadly reactive human CD8 T cells that recognize an epitope conserved between VZV, HSV and EBV. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004008. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, L.; Laing, K.J.; Dong, L.; Russel, R.M.; Barlow, R.S.; Haas, J.G.; Ramchandani, M.S.; Johnston, C.; Buus, S.; Redwood, A.J.; et al. Extensive CD4 and CD8 T-cell cross-reactivity between alphaherpesviruses. J. Immunol. 2016, 195, 2205–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulla, A.F.; Normatov, M.G.; Supasitthumrong, T.; Maes, M. Molecular mimicry between Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus-6 proteins and central nervous system proteins: Implications for T and B cell immunogenicity in an in silico study. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K.; Nisenbaum, R.; Stewart, G.; Thompson, W.W.; Robin, L.; Washko, R.M.; Noah, D.L.; Barrett, D.H.; Randall, B.; Herwaldt, B.L.; et al. Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War. J. Am. Med. Soc. 1998, 280, 981–998. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, L. Prevalence and patterns of Gulf War Illness in Kansas veterans: Association of symptoms with characteristics of person, place and time of military service. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 152, 992–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Vojdani, A.; Thrasher, J.D. Cellular and humoral immune antibodies in Gulf War veterans. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maloney, S.R.; Jensen, S.; Gil-Rivas, V.; Goolkasian, P. Latent viral immune inflammatory response model for chronic multisystem illness. Med. Hypothesis 2013, 80, 220–229. [Google Scholar]

- Bast, E.; Jester, D.J.; Palacio, A.; Krengel, M.; Reinhard, M.; Ashford, J.W. Gulf War illness: A historical review and considerations of a post-viral syndrome. Mil. Med. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, B.; Goolkasian, P.; Mena-Palomo, I.; Williams, M.V.; Maloney, S.R.; Ariza, M.E. Reactivation of latent herpesviruses and a faulty antiviral response may contribute to chronic multi-system and multi-system illnesses in U.S. military veterans. J. Med. Virol. 2025, 97, e70400. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett, D.A.; Hotchkiss, A.K.; Pyter, L.M.; Nelson, R.J.; Yang, E.; Yeh, P.E.; Litsky, M.; Williams, M.; Glaser, R. Epstein-Barr Virus-Encoded dUTPase Modulates Immune Function and Induces Sickness Behavior in Mice. J. Med. Virol. 2004, 74, 442–448. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, R.; Litsky, M.L.; Padgett, D.A.; Baiocchi, R.A.; Yang, E.V.; Chen, M.; Yeh, P.E.; Green-Church, K.B.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Williams, M. EBV-encoded dUTPase induces immune dysregulation: Implications for the pathophysiology of EBV-associated malignant disease. Virology 2006, 346, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, W.J.; Williams, M.V.; Lemeshow, S.A.; Binkley, P.; Guttridge, D.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Knight, D.A.; Guttridge, K.; Glaser, R. Epstein-Barr virus encoded dUTPase enhances proinflammatory cytokine production by macrophages in contact with endothelial cells: Evidence for depression-induced atherosclerotic risk. Brain Behav. Immun. 2008, 22, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, M.E.; Glaser, R.; Kaumaya, P.T.P.; Jones, C.; Williams, M. The Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)-Encoded dUTPase Activates NF-kappa B through the TLR2 and MyD88-dependent Signaling Pathway. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.M.; Ariza, M.E.; Williams, M.; Jason, L.; Beqaj, S.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Lemeshow, S.; Glaser, R. Antibody to Epstein-Barr Virus deoxyuridine triphosphate nucleotidohydrolase and deoxyribonucleotide polymerase in a Chronic Fatigue Syndrome subset. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47891. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, M.E.; Glaser, R.; Williams, M.V. Human herpesviruses encoded dUTPases: A family of proteins that modulate dendritic cells function and innate immunity. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrecht, T.G.; Salloum, B.A.; Ariza, M.E.; Williams, M.; Reader, B.; Glaser, R.; Sheridan, J.; Nelson, R.J. Restraint induces sickness responses independent of injection with Epstein-Barr virus-encoded dUTPase. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2014, 4, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrecht, T.G.; Weil, Z.M.; Salloum, B.A.; Ariza, M.E.; Williams, M.; Reader, B.; Glaser, R.; Sheridan, J.; Nelson, R.J. Chronic physical stress does not interact with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) encoded dUTPase to alter the sickness response. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2015, 5, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.V.; Cox, B.; Alharshawi, K.; Lafuse, W.P.; Ariza, M.E. Epstein-Barr virus dUTPase contributes to neuroinflammation in a cohort of patients with Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Clin. Ther. 2019, 41, 848–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza, M.E. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: The human herpesviruses are back! Biomolecules 2021, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza, M.E.; Cox, B.; Martinez, B.; Mena-Palomo, I.; Zarate, G.J.; Williams, M.V. Viral dUTPases: Modulators of Innate Immunity. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharshawi, K.; Cox, B.; Ariza, M.E. Examination of control asymptomatic cohorts reveals heightened anti-EBV and HHV-6A/B dUTPase antibodies in the aging population. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 3464–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hollmann, C.; Kalanidhi, S.; Grothey, A.; Keating, S.; Mena-Palomo, I.; Schlosser, L.S.; Kaiping, A.; Scheller, C.; Sotzny FHorn, A.; et al. Increased circulating fibronectin, depletion of natural IgM and heightened EBV, HSV-1 reactivation in ME/CFS and long COVID. MedRxiv 2023. preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Gentilotti, E.; Gorska, A.; Tami, A.; Gusinow, R.; Miramdola, M.; Bario, J.R.; Baena, Z.R.P.; Rossi, E.; Hasenauer, J.; Lopes-Rafegas, I.; et al. Clinical phenotypes and quality of life to define post-COVID-19 syndrome: A cluster analysis of the multinational, prospective ORCHESTRA cohort. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 62, 102107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komaroff, A.L.; Lipkin, W.I. ME/CFS and Long COVID share similar symptoms and biological abnormalities: Road map to the literature. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1187163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; Janowski, A.J.; Lesnak, J.B.; Hayashi, K.; Dailey, D.L.; Chimenti, R.; Frey-Law, L.A.; Sluka, K.A.; Berardi, G. A comparison of pain, fatigue, and function between post–COVID-19 condition, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome: A survey study. Pain 2023, 164, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppercorn, K.; Edgar, C.D.; Kleffmann, T.; Tate, W.O. A pilot study on the immune cell proteome of long COVID patients shows changes to physiological pathways similar to those in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2023, 12, 22068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleman, B.; Charlton, B.T.; Goulding, R.P.; Kerkhoff, T.J.; Breedveld, E.A.; Noort, W.; Offringa, C.; Bloemers, F.W.; van Weeghel, M.; Schomakers, B.V.; et al. Muscle abnormalities worsen after post-exertional malaise in long COVID. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, T.L.; Weitzer, D.J. Long COVID and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)—A systemic review and comparison of clinical presentation and symptomatology. Medicina 2021, 57, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jason, L.A.; Dorri, J.A. ME/CFS and post-exertional malaise among patients with Long COVID. Neurol. Int. 2022, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, H.; Quach, T.C.; Tiwari, A.; Bonilla, A.E.; Miglis, M.; Yang, P.C.; Eggert, L.E.; Sharifi, H.; Horomanski, A.; Subramanian, A.; et al. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is common in post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC): Results from a post-COVID-19 multidisciplinary clinic. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1090747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, J.E.; Okyay, R.A.; Licht, W.E.; Hurley, D.J. Investigation of long COVID prevalence and its relationship to Epstein-Barr virus reactivation. Pathogens 2021, 10, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Cao, S.; Dong, H.; Lv, H.; Teng, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Qin, Y.; Chai, Y.; et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of critically ill patients with acute COVID-19 with Epstein-Barr virus reactivation. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolucci, S.; Cassaniti, I.; Novazzi, F.; Fiorina, L.; Piralla, A.; Comolli, G.; Bruno, R.; Maserati, R.; Gulminetti, R.; Novati, S.; et al. COVID-19 Task Force. EBV DNA increase in COVID-19 patients with impaired lymphocyte subpopulation count. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 104, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, K.D.E.; Whitehurst, C.B. Incidence of Epstein-Barr virus reactivation is elevated in COVID-19 patients. Virus Res. 2023, 334, 199157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.H.; Ragusa, M.; Tortosa, F.; Torres, A.; Gresh, L.; Mendez-Rico, J.A.; Alvarez-Moreno, C.A.; Lisboa, T.C.; Valderrama-Beltran, S.L.; Aldighieri, S.; et al. Viral reactivations and co-infections in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Yuan, D.; Chen, D.G.; Ng, R.H.; Wang, K.; Choi, J.; Li, S.; Hong, S.; Zhang, R.; Xie, J.; et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post- acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell 2022, 185, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peluso, M.J.; Deveau, T.M.; Munter, S.E.; Ryder, D.; Buck, A.; Beck-Engeser, G.; Chan, F.; Lu, S.; Goldberg, S.A.; Hoh, R.; et al. Chronic viral coinfections differentially affect the likelihood of developing long COVID. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e163669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, D.; Church, T.M.; Swaminathan, S. Epstein-Barr virus lytic replication induces ACE2 expression and enhances SARS-CoV-2 pseudotyped virus entry in epithelial cells. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e0019221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Wood, J.; Jaycox, J.R.; Dhodapkar, R.M.; Lu, P.; Gehlhausen, J.R.; Tabachnikova, A.; Greene, K.; Tabacof, L.; Malik, A.A.; et al. Distinguishing features of long COVID identified through immune profiling. Nature 2023, 623, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karachaliou, M.; Ranzani, O.; Espinosa, A.; Iraola-Guzman, S.; Castano-Vinyals, G.; Vidal, M.; Jimenez, A.; Banus, M.; Nogues, E.A.; Aguilar, R.; et al. Antibody responses to common viruses according to COVID-19 severity and postacute sequelae of COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, F.; Efstahiou, C.; Fontanella, S.; Richardson, M.; Saunders, R.; Swieboda, D.; Sidhu, J.K.; Ascough, S.; Moore, S.C.; Mohamed, N.; et al. Large-scale phenotyping of patients with long COVID post-hospitalization reveals mechanistic subtypes of disease. Nat. Immunol. 2024, 25, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, A.; Athar, M.M.T.; Amini, M.J.; Hajishah, H.; Siahvoshi, S.; Jalali, M.; Jahanbakhshi, B.; Mozhagani, S.H. Reactivation of herpesviruses during COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Med. Virol. 2023, 33, e2437. [Google Scholar]

- Banko, A.; Miljanovic, D.; Cirkovic, A. Systematic review with meta-analysis of active herpesvirus infections in patients with COVID-19: Old players on the new field. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 130, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, S.; Deb, P.; Parveen, M.; Zannat, K.E.; Bhuiyan, A.H.; Yeasmin, M.; Molla, M.M.A.; Saif-Ur-Rahman, K.M. Clinical features and outcomes of COVID-19 patients with concomitant herpesvirus co-infection or reactivation: A systematic review. New Microbes New Infect. 2024, 58, 101223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderova, P.; Mizera, J.; Gharibian, A.; Manukyan, G.; Raska, M.; Gajdos, P.; Kosztyu, P.; Genzor, S.; Kudelka, M.; Sova, M.; et al. The SARS-Co-V-2 trigger highlights host interleukin 1 genetics in Epstein-Barr virus reactivation. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115859. [Google Scholar]

- Manoharan, S.; Ying, L.Y. Epstein Barr virus reactivation during COVID-19 hospitalization significantly increased mortality/death in SARS-CoV-2(+)/ EBV(+) than SARS-CoV-2(+)/EBV (−) patients: A comparative meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2023, 2023, 1068000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattei, A.; Schiavoni, L.; Riva, E.; Ciccozzi, M.; Veralli, R.; Urselli, A.; Citriniti, V.; Nenna, A.; Pascarella, G.; Costa, F.; et al. Epstein–Barr virus, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes Simplex-1/2 reactivations in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2024, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, C.; Chen, J.; Rouphael, N.; Pickering, H.; Hoang Van Phan, H.; Glascock, A.; Chu, V.; Dandekar, R.; Corry, D.; Kheradmand, F.; et al. Chronic Viral Reactivation and Associated Host Immune Response and Clinical Outcomes in Acute COVID-19 and Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeggerl, A.D.; Nunhofer, V.; Lauth, W.; Badstuber, N.; Held, N.; Zimmermann, G.; Grabmer, C.; Weidner, L.; Jungbauer, C.; Lindbauer, N.; et al. Epstein-Barr virus reactivation is not causative for post-COVID-19-syndrome in individuals with asymptomatic or mild SARS-CoV-2 disease course. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, R.S.; Nieters, A.; Göpel, S.; Merle, U.; Steinacker, J.M.; Deibrert, P.; Friedmann-Bette, B.; Nieß, A.; Müller, B.; Schilling, C.; et al. Persistent symptoms and clinical findings in adults with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19/post-COVID-19 syndrome in the second year after acute infection: A population-based, nested case-control study. PLoS Med. 2025, 22, e100451. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, B.S.; Alharshawi, K.; Mena-Palomo, I.; Lafuse, W.P.; Ariza, M.E. EBV/HHV-6A dUTPases contribute to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome pathophysiology by enhancing TFH cell differentiation and extrafollicular activities. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e158193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Virus | Prevalence (%) | Age of Primary Infection | Site of Productive Infection | Site of Latency | Common Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-1 [42,43] | 70 | 0.5–5 yrs | Epithelial cells | Trigeminal Ganglia | Oral herpes |

| HSV-2 [42,43] | 20–25 | 15–49 years | Epithelial cells | Sacral Ganglia | Genital herpes |

| VZV [42,43] | >95 | 5–9 years | Epithelial cells | Dorsal Root Ganglia | Chickenpox and zoster |

| HCMV [42,44] | 50–>90 | 5–40 years | Epithelial and Endothelial cells | Myeloid Cell Linage | Immunosuppressed Transplant |

| HHV-6A [42,45] | >95 | 0.5–2 years | CD4+ T cells | Monocyte/Macrophage Cell Linage | Immunosuppressed Transplant |

| HHV-6B [42,45] | >95 | 0.5–2 years | CD4+ T cells | Monocyte/Macrophage Cell Linage | Infantum roseola (sixth disease) |

| HHV-7 [42,46] | >95 | 1.5–3 years | CD4+ T cells | Monocyte/Macrophage Cell Linage | Neurological ? |

| EBV [42,47] | >95 | 3–4 years 10–30 years | Epithelial and Plasma cells | Memory B cell | Infectious mononucleosis, various lymphomas, and gastric carcinoma |

| HHV-8 [42,48] | 5–50 | 4 years in endemic areas | Epithelial, Epithelial, and Plasma cells | Epithelial, Endothelial, and B cells | Kaposi lymphoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman’s Disease |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ariza, M.E.; Mena Palomo, I.; Williams, M.V. Does Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Represent a Poly-Herpesvirus Post-Virus Infectious Disease? Viruses 2025, 17, 1624. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121624

Ariza ME, Mena Palomo I, Williams MV. Does Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Represent a Poly-Herpesvirus Post-Virus Infectious Disease? Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1624. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121624

Chicago/Turabian StyleAriza, Maria Eugenia, Irene Mena Palomo, and Marshall V. Williams. 2025. "Does Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Represent a Poly-Herpesvirus Post-Virus Infectious Disease?" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1624. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121624

APA StyleAriza, M. E., Mena Palomo, I., & Williams, M. V. (2025). Does Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Represent a Poly-Herpesvirus Post-Virus Infectious Disease? Viruses, 17(12), 1624. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121624