Sequential Dengue Virus Infection in Marmosets: Histopathological and Immune Responses in the Liver

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Virus Strains

2.3. Experimental Infection Protocol

2.4. Confirmation of DENV Infection in NHPs

2.5. Histopathological Processing and Microscopic Evaluation

2.6. Immunohistochemistry

2.7. Histopathology

2.8. Immunophenotyping and Cytokine Expression in Liver Tissue

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

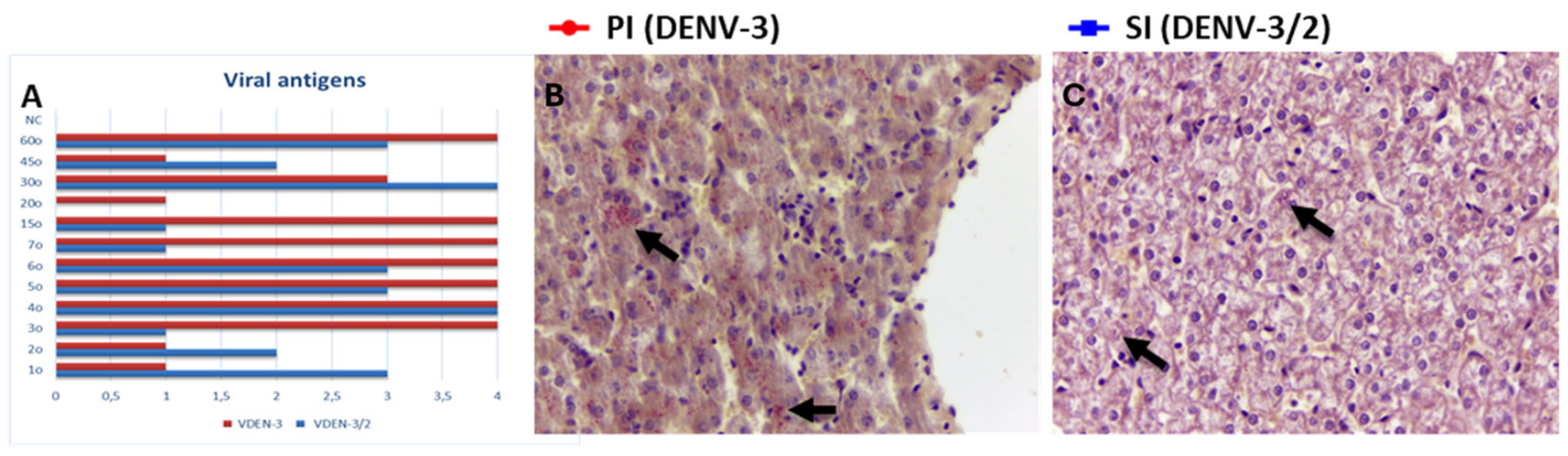

3.1. Detection of Viral Antigen in Liver Tissue

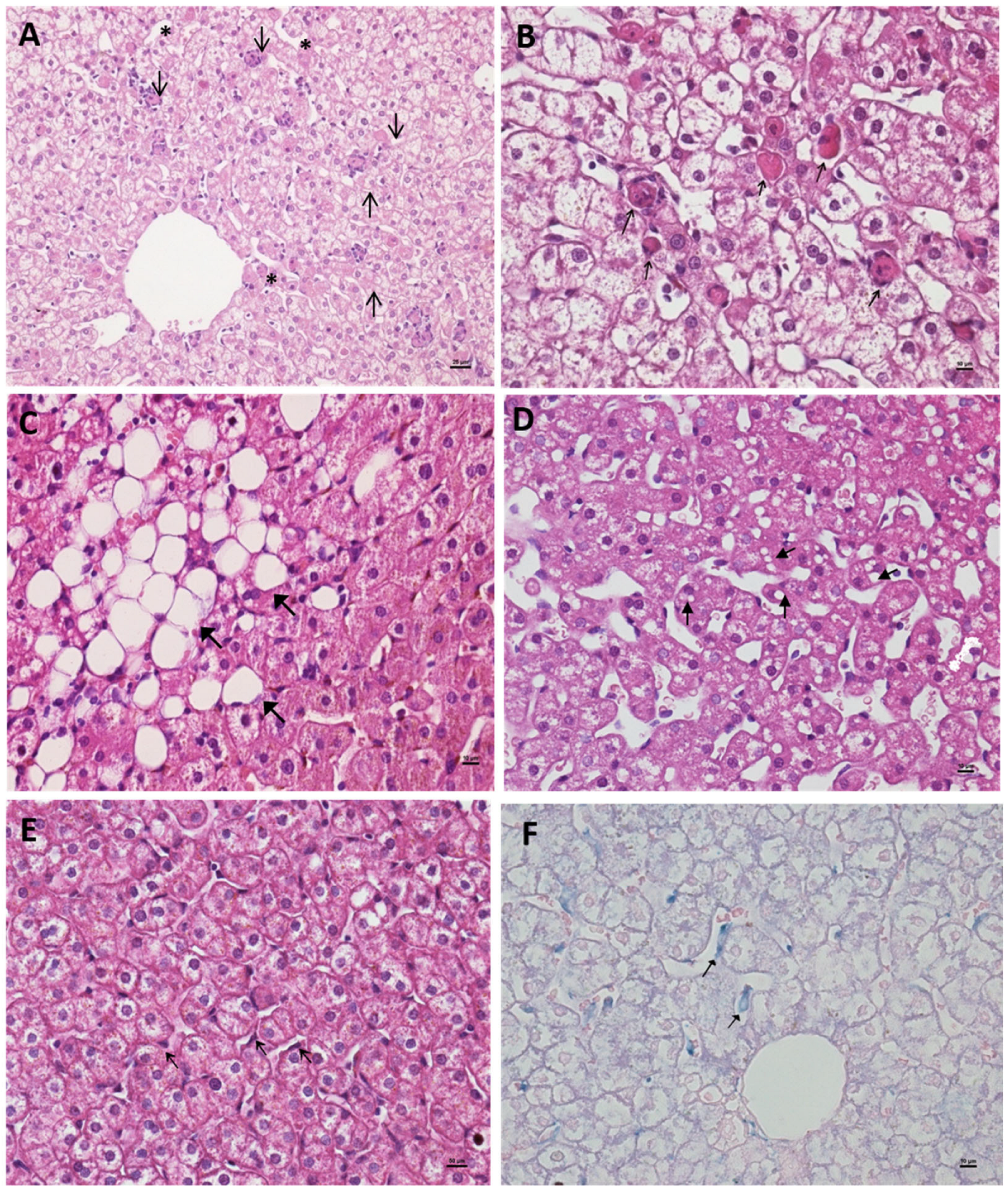

3.2. Liver Histopathological Characterization Following Primary and Sequential Dengue Virus Infections

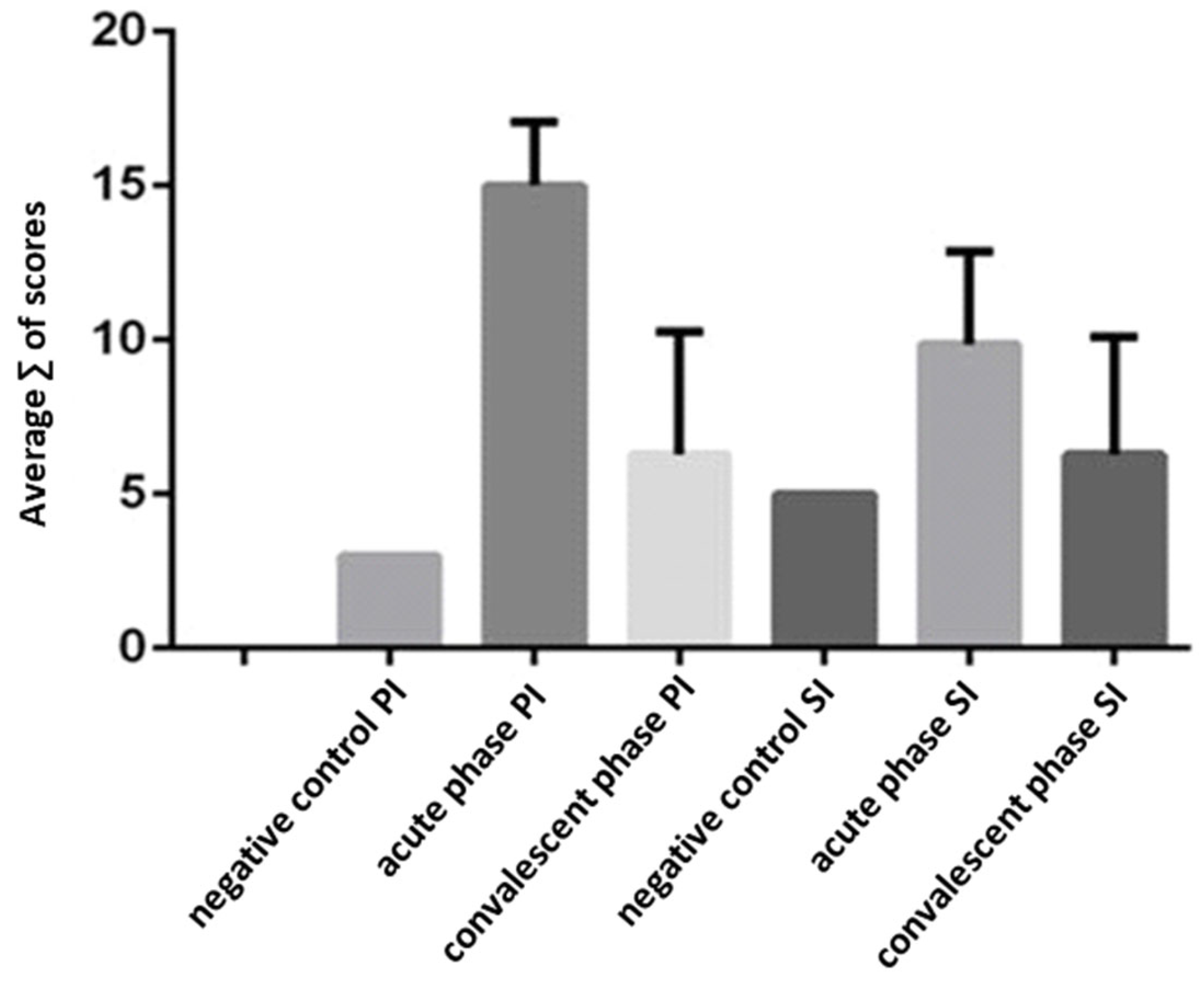

3.3. Hepatitis Characterization in Primary (DENV-3) and Secondary (DENV-3/2) Infections

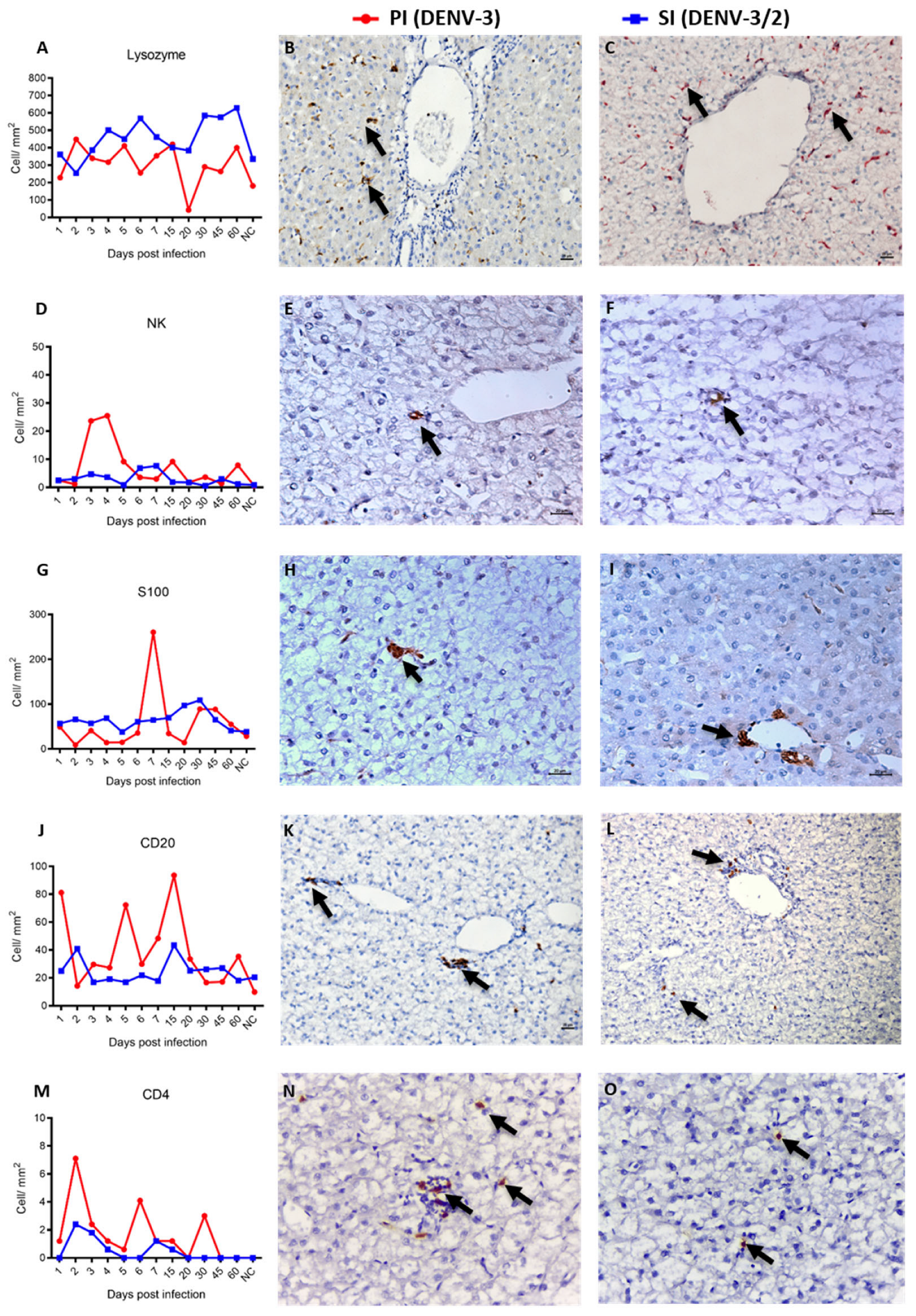

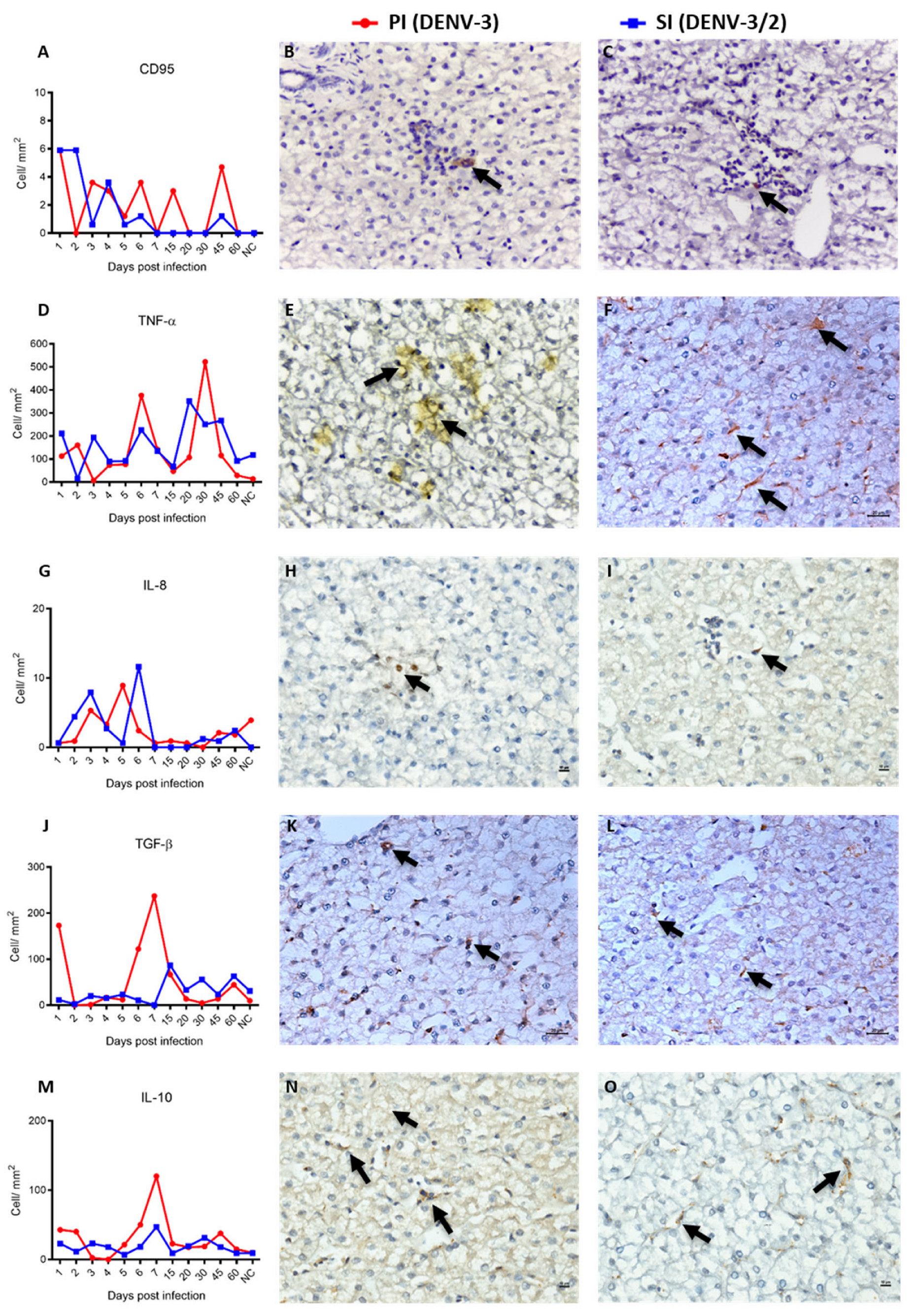

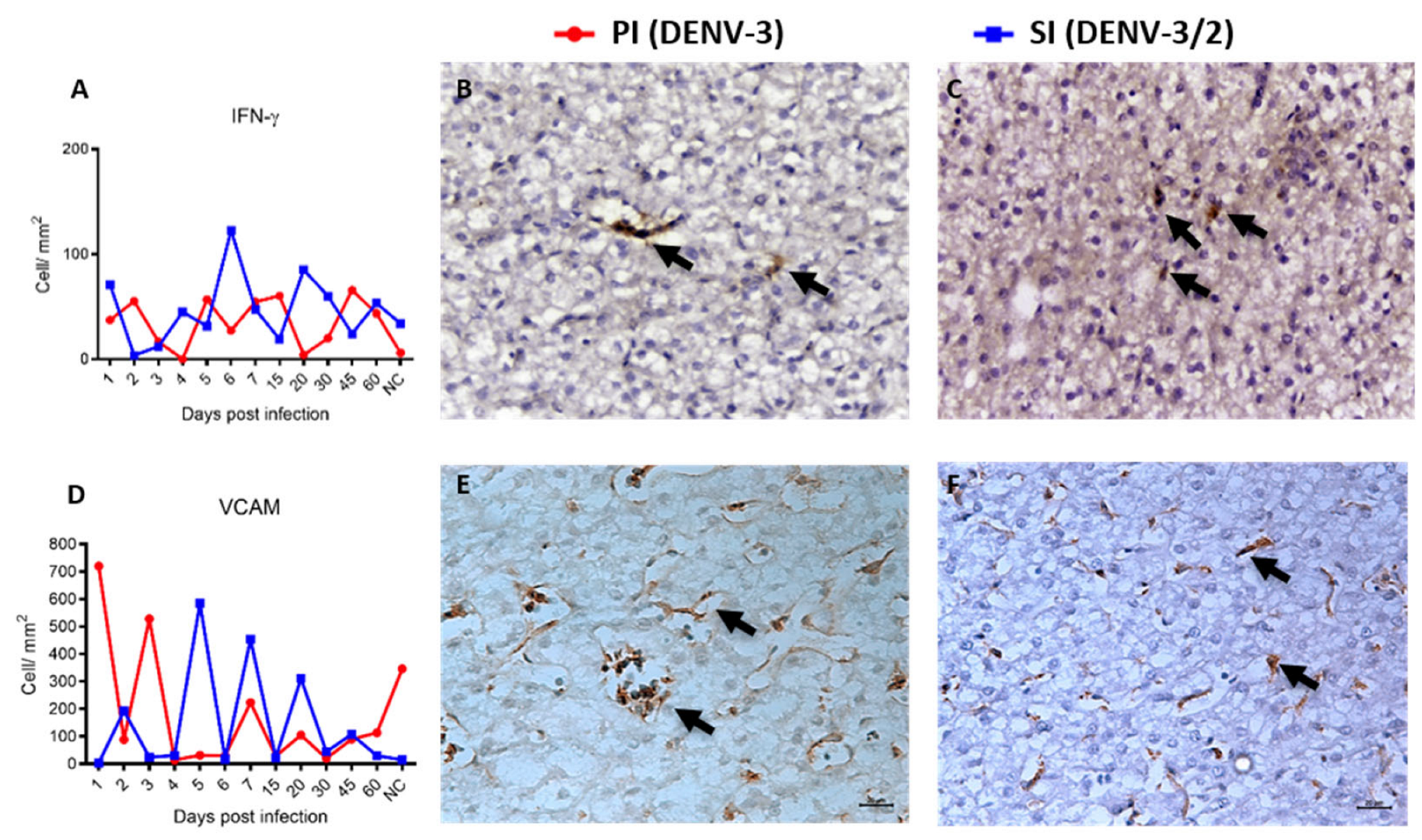

3.4. Characterization of Hepatic Immunophenotype and Cytokine Profile in Non-Human Primates Following Sequential Dengue Virus Infection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silva, E.M.d.; Oliveira, G.V.; Brito, P.H.A.d.; Consolin, E.M.; Brito, P.F.; Franco, M.C.; Melo, L.V.; Bordon, L.B.; Sena, A.L.; Lima, V.O.; et al. A ocorrência de dengue no Brasil na última década: Avanços e desafios. Braz. J. Health Rev. 2024, 7, e71302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzelnick, L.C.; Coloma, J.; Harris, E. Dengue: Knowledge gaps, unmet needs, and research priorities. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e88–e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Quam, M.B.M.; Zhang, T.; Sang, S. Global burden for dengue and the evolving pattern in the past 30 years. J. Travel Med. 2021, 28, taab146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, T.M.; Tomashek, K.M.; Read, J.S.; Margolis, H.S.; Waterman, S.H. A New Look at an Old Disease: Recent Insights into the Global Epidemiology of Dengue. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2017, 4, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, R.; Surasombatpattana, P.; Wichit, S.; Dauvé, A.; Donato, C.; Pompon, J.; Vijaykrishna, D.; Liegeois, F.; Vargas, R.M.; Luplertlop, N.; et al. Phylogenetic analysis revealed the co-circulation of four dengue virus serotypes in Southern Thailand. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aring, B.J.; Gavali, D.M.B.; Kateshiya, P.R.; Gadhvi, H.M.; Mullan, S.; Trivedi, K.K.; Nathametha, A.A.; Nakhava, A.H. Co-circulation of all the Four Serotype of Dengue Virus in Endemic Region of Saurashtra, Gujarat during 2019-2020 Season. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2021, 15, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisher, C.H.; Karabatsos, N.; Dalrymple, J.M.; Shope, R.E.; Porterfield, J.S.; Westaway, E.G.; Brandt, W.E. Antigenic Relationships between Flaviviruses as Determined by Cross-neutralization Tests with Polyclonal Antisera. J. Gen. Virol. 1989, 70, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; 147p, Available online: https://www.paho.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/2009-cde-dengue-guidelines-diagnosis-treatment-prevention-control.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Nisalak, A.; Endy, T.P.; Nimmannitya, S.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Thisayakorn, U.; Scott, R.M.; Burke, D.S.; Hoke, C.H.; Innis, B.L.; Vaughn, D.W. Serotype-specific dengue virus circulation and dengue disease in bangkok, thailand from 1973 to 1999. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 68, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, T. Dengue haemorrhagic fever: A pathological study. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1968, 62, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.; Shroyer, D.A.; Tesh, R.B.; Freier, J.E.; Lien, J.C. Transovarial Transmission of Dengue Viruses by Mosquitoes: Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1983, 32, 1108–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessie, K.; Fong, M.Y.; Devi, S.; Lam, S.K.; Wong, K.T. Localization of Dengue Virus in Naturally Infected Human Tissues, by Immunohistochemistry and In Situ Hybridization. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 189, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paes, M.V.; Lenzi, H.L.; Nogueira, A.C.M.; Nuovo, G.J.; Pinhão, T.; Mota, E.M.; Basílio-De-Oliveira, C.A.; Schatzmayr, H.; Barth, O.M.; De Barcelos Alves, A.M. Hepatic damage associated with dengue-2 virus replication in liver cells of BALB/c mice. Lab. Investig. 2009, 89, 1140–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado, D.M.; Eltit, J.M.; Mansfield, K.D.; Panqueba, C.; Castro, D.; Vega, M.R.; Xhaja, K.S.; Schmidt, D.; Martin, K.J.; Allen, P.D.; et al. Heart and Skeletal Muscle Are Targets of Dengue Virus Infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2010, 29, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Póvoa, T.F.; Alves, A.M.B.; Oliveira, C.A.B.; Nuovo, G.J.; Chagas, V.L.A.; Paes, M.V. The Pathology of Severe Dengue in Multiple Organs of Human Fatal Cases: Histopathology, Ultrastructure and Virus Replication. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e83386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Póvoa, T.F.; Oliveira, E.R.A.; Basílio-De-Oliveira, C.A.; Nuovo, G.J.; Chagas, V.L.A.; Salomão, N.G.; Mota, E.M.; Paes, M.V. Peripheral Organs of Dengue Fatal Cases Present Strong Pro-Inflammatory Response with Participation of IFN-Gamma-, TNF-Alpha- and RANTES-Producing Cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.Y.; Ho, T.; Lai, M.; Tan, S.S.; Chen, T.; Lee, M.; Chien, Y.; Chen, Y.; Perng, G.C. Identification and characterization of permissive cells to dengue virus infection in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Transfusion 2019, 59, 2938–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.V.; Fagundes, C.T.; Souza, D.G.; Teixeira, M.M. Inflammatory and innate immune responses in dengue infection: Protection versus disease induction. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 182, 1950–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guabiraba, R.; Ryffel, B. Dengue virus infection: Current concepts in immune mechanisms and lessons from murine models. Immunology 2014, 141, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliari, C.; Quaresma, J.A.S.; Fernandes, E.R.; Stegun, F.W.; Brasil, R.A.; de Andrade, H.F.; Barros, V.; Vasconcelos, P.F.C.; Duarte, M.I.S. Immunopathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever: Contribution to the study of human liver lesions. J. Med. Virol. 2013, 86, 1193–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, J.; Ahmad, S.Q.; Rafi, T. Postmortem Findings In Fatal Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2018, 28, S137–S139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, A.; Gutiérrez-Barbosa, H.; Lyke, K.E.; Chua, J.V. Immune-Mediated Pathogenesis in Dengue Virus Infection. Viruses 2022, 14, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Y.K.; Wong, W.F.; Vignesh, R.; Chattopadhyay, I.; Velu, V.; Tan, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Larsson, M.; Shankar, E.M. Dengue Infection—Recent Advances in Disease Pathogenesis in the Era of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 889196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tin, E.N.; Komarasamy, T.V.; Adnan, N.A.A.; Balasubramaniam, V.R.M.T. Dengue virus infection: Immune response and thera-peutic targets. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2025, 112, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.; Pichyangkul, S.; Vaughn, D.W.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Nimmannitya, S.; Nisalak, A.; Kurane, I.; Rothman, A.L.; Ennis, F.A. Early CD69 Expression on Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes from Children with Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 180, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weg, C.A.M.V.D.; Pannuti, C.S.; De Araújo, E.S.A.; Ham, H.-J.V.D.; Andeweg, A.C.; Boas, L.S.V.; Felix, A.C.; Carvalho, K.I.; De Matos, A.M.; Levi, J.E.; et al. Microbial Translocation Is Associated with Extensive Immune Activation in Dengue Virus Infected Patients with Severe Disease. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solórzano, V.E.F.; Faria, N.R.d.C.; dos Santos, C.F.; Corrêa, G.; Cipitelli, M.d.C.; Ribeiro, M.D.; de Souza, L.J.; Damasco, P.V.; da Cunha, R.V.; dos Santos, F.B.; et al. Different Profiles of Cytokines, Chemokines and Coagulation Mediators Associated with Severity in Brazilian Patients Infected with Dengue Virus. Viruses 2021, 13, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.; Sucila, T.G. Pathophysiologic and Prognostic Role of Proinflammatory and Regulatory Cytokines in Dengue Fever. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 4, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jusof, F.F.; Lim, C.K.; Aziz, F.N.; Soe, H.J.; Raju, C.S.; Sekaran, S.D.; Guillemin, G.J. The Cytokines CXCL10 and CCL2 and the Kynurenine Metabolite Anthranilic Acid Accurately Predict Patients at Risk of Developing Dengue With Warning Signs. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 1964–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, D.B.; Flobbe, K.; Xuan, C.; Phuong, T.; Day, N.P.J.; Phuong, P.T.; Buurman, W.A.; Cardosa, M.J.; White, N.J.; Kwiatkowski, D. Pathophysiologic and Prognostic Role of Cytokines in Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. J. Infect. Dis. 1998, 177, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozza, F.A.; Cruz, O.G.; Zagne, S.M.; Azeredo, E.L.; Nogueira, R.M.; Assis, E.F.; Bozza, P.T.; Kubelka, C.F. Multiplex cytokine profile from dengue patients: MIP-1beta and IFN-gamma as predictive factors for severity. BMC Infect. Dis. 2008, 8, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção-Miranda, I.; Amaral, F.A.; Bozza, F.A.; Fagundes, C.T.; Sousa, L.P.; Souza, D.G.; Pacheco, P.; Barbosa-Lima, G.; Gomes, R.N.; Bozza, P.T.; et al. Contribution of Macrophage Mi-gration Inhibitory Factor to the Pathogenesis of Dengue Virus Infection. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-Oliveira-Pinto, L.M.; Marinho, C.F.; Povoa, T.F.; De Azeredo, E.L.; De Souza, L.A.; Barbosa, L.D.R.; Motta-Castro, A.R.C.; Alves, A.M.B.; Ávila, C.A.L.; De Souza, L.J.; et al. Regulation of Inflammatory Chemokine Receptors on Blood T Cells Associated to the Circulating Versus Liver Chemokines in Dengue Fever. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patro, A.R.K.; Mohanty, S.; Prusty, B.K.; Singh, D.K.; Gaikwad, S.; Saswat, T.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Das, B.K.; Tripathy, R.; Ravindran, B. Cytokine Signature Associated with Disease Severity in Dengue. Viruses 2019, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puc, I.; Ho, T.-C.; Yen, K.-L.; Vats, A.; Tsai, J.-J.; Chen, P.-L.; Chien, Y.-W.; Lo, Y.-C.; Perng, G.C. Cytokine Signature of Dengue Patients at Different Severity of the Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Varma, M.; Sood, V.; Ambikan, A.; Jayaram, A.; Babu, N.; Gupta, S.; Mukhopadhyay, C.; Neogi, U. Temporal cytokine storm dynamics in dengue infection predicts severity. Virus Res. 2024, 341, 199306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamarapravati, N. Pathology of Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever. In Monograph on Dengue/Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever; World Health Organization: New Delhi, India, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Zompi, S.; Harris, E. Animal Models of Dengue Virus Infection. Viruses 2012, 4, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayesh, M.E.H.; Tsukiyama-Kohara, K. Mammalian animal models for dengue virus infection: A recent overview. Arch. Virol. 2021, 167, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronel-Ruiz, C.; Gutiérrez-Barbosa, H.; Medina-Moreno, S.; Velandia-Romero, M.L.; Chua, J.V.; Castellanos, J.E.; Zapata, J.C. Humanized Mice in Dengue Research: A Comparison with Other Mouse Models. Vaccines 2020, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubler, D.J. Epidemic dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever as a public health, social and economic problem in the 21st century. Trends Microbiol. 2002, 10, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami, N.A.M.; Takasaki, T.; Kurane, I.; Moi, M.L. Non-Human Primate Models of Dengue Virus Infection: A Comparison of Viremia Levels and Antibody Responses during Primary and Secondary Infection among Old World and New World Monkeys. Pathogens 2020, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilakis, N.; Cardosa, J.; Hanley, K.A.; Holmes, E.C.; Weaver, S.C. Fever from the forest: Prospects for the continued emergence of sylvatic dengue virus and its impact on public health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onlamoon, N.; Noisakran, S.; Hsiao, H.-M.; Duncan, A.; Villinger, F.; Ansari, A.A.; Perng, G.C. Dengue virus–induced hemorrhage in a nonhuman primate model. Blood 2010, 115, 1823–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omatsu, T.; Moi, M.L.; Hirayama, T.; Takasaki, T.; Nakamura, S.; Tajima, S.; Ito, M.; Yoshida, T.; Saito, A.; Katakai, Y.; et al. Common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) as a primate model of dengue virus infection: Development of high levels of viraemia and demonstration of protective immunity. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 2272–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omatsu, T.; Moi, M.L.; Takasaki, T.; Nakamura, S.; Katakai, Y.; Tajima, S.; Ito, M.; Yoshida, T.; Saito, A.; Akari, H.; et al. Changes in hematological and serum biochemical parameters in common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) after inoculation with dengue virus. J. Med. Primatol. 2012, 41, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, V.L.; de Souza, J.T.; Costa, Z.G.A.; de Araujo, M.T.F.; Braga, R.R. Diagnóstico de Febre Hemorrágica em Primata Não Humano Causado pelo Vírus Dengue: Relato de Caso. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2009, 42, 484. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M.S.; de Castro, P.H.G.; Silva, G.A.; Casseb, S.M.M.; Júnior, A.G.D.; Rodrigues, S.G.; Azevedo, R.D.S.d.S.; e Silva, M.F.C.; Zauli, D.A.G.; Araújo, M.S.S.; et al. Callithrix penicillata: A feasible experimental model for dengue virus infection. Immunol. Lett. 2014, 158, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.W.; Russell, B.J.; Lanciotti, R.S. Serotype-Specific Detection of Dengue Viruses in a Fourplex Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase PCR Assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 4977–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, A. Isolation of a Singh’s Aedes albopictus Cell Clone Sensitive to Dengue and Chikungunya Viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 1978, 40, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubler, D.J.; Kuno, G.; Sather, G.E.; Velez, M.; Oliver, A. Mosquito Cell Cultures and Specific Monoclonal Antibodies in Surveillance for Dengue Viruses. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1984, 33, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.S. Estudo Experimental sobre a Resposta Imunológica em Infecções Sequenciais pelo Vírus Dengue 3 e pelo Vírus Dengue 2 em Primatas Não Humanos da Espécie Callithrix Penicillata; Universidade Federal do Pará: Belém, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Travassos da Rosa, A.P.A.; Travassos da Rosa, E.S.; Travassos da Rosa, J.F.S.; Dégallier, N.; Vasconcelos, P.F.C.; Rodrigues, S.G.; Cruz, A.C.R. Os Arbovírus no Brasil: Generalidades, Métodos e Técnicas de Estudo; Documento Técnico nº 2; Instituto Evandro Chagas/Fundação Nacional de Saúde: Belém, Brazil, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, W.C.; Crowell, T.P.; Watts, D.M.; Barros, V.L.R.; Kruger, H.; Pinheiro, F.; Peters, C.J. Demonstration of Yellow Fever and Dengue Antigens in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Human Liver by Immunohistochemical Analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1991, 45, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, J.A.S.; Barros, V.L.R.S.; Fernandes, E.R.; Pagliari, C.; Takakura, C.; Vasconcelos, P.F.d.C.; de Andrade, H.F.; Duarte, M.I.S. Reconsideration of histopathology and ultrastructural aspects of the human liver in yellow fever. Acta Trop. 2005, 94, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishak, K.; Baptista, A.; Bianchi, L.; Callea, F.; De Groote, J.; Gudat, F.; Denk, H.; Desmet, V.; Korb, G.; MacSween, R.N.; et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 1995, 22, 696–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, P.P.; Ishak, K.G.; Nayak, N.C.; Poulsen, H.E.; Scheuer, P.J.; Sobin, L.H. The Morphology of Acute Hepatitis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- MacSween, R.N.M.; Burt, A.D.; Portmann, B.; Hübscher, S.; Ferrell, L.; Schmid, M. MacSween’s Pathology of the Liver, 6th ed.; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, A.D.; Ferrell, L.D.; Hübscher, S.G. Morphology of the Liver, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitch, J.H. Anatomic Pathology of the Liver, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dancey, C.; Reidy, J. Statistics Without Mathematics for Psychology: Using SPSS for Windows; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, P.M.; Rocha, T.C.D.; Andreotti, R.; Gomes, E.C.; Silva, M.A.N.; Svoboda, W.K.; Nunes, J.; Guerreiro, S.R.; Chiang, J.O.; Vasconcelos, P.F.C. Serosurvey of Arbovirus in Free-Living Non-Human Primates (Sapajus spp.) in Brazil. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2015, 2, 2380–2391.1000155. [Google Scholar]

- Bhamarapravati, N.; Tuchinda, P.; Boonyapaknavik, V. Pathology of Thailand haemorrhagic fever: A study of 100 autopsy cases. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1967, 61, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerre, M.R.; Lan, N.T.; Marianneau, P.; Hue, N.B.; Khun, H.; Hung, N.T.; Khen, N.T.; Drouet, M.T.; Huong, V.T.; Ha, D.Q.; et al. Liver Histopathology and Biological Correlates in Five Cases of Fatal Dengue Fever in Vietnamese Children. Virchows Arch. 2001, 438, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aye, K.S.; Charngkaew, K.; Win, N.; Wai, K.Z.; Moe, K.; Punyadee, N.; Thiemmeca, S.; Suttitheptumrong, A.; Sukpanichnant, S.; Prida, M.; et al. Pathologic highlights of dengue hemorrhagic fever in 13 autopsy cases from Myanmar. Hum. Pathol. 2014, 45, 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moragas, L.J.; Alves, F.d.A.V.; Oliveira, L.d.L.S.; Salomão, N.G.; Azevedo, C.G.; da Silva, J.F.R.; Basílio-De-Oliveira, C.A.; Basílio-De-Oliveira, R.; Mohana-Borges, R.; de Carvalho, J.J.; et al. Liver immunopathogenesis in fatal cases of dengue in children: Detection of viral antigen, cytokine profile and inflammatory mediators. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1215730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Y.P.; Falcão, L.F.M.; Smith, V.C.; de Sousa, J.R.; Pagliari, C.; Franco, E.C.S.; Cruz, A.C.R.; Chiang, J.O.; Martins, L.C.; Nunes, J.A.L.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Human Hepatic Lesions in Dengue, Yellow Fever, and Chikungunya: Revisiting Histopathological Changes in the Light of Modern Knowledge of Cell Pathology. Pathogens 2023, 12, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.S.; Moita, L.A.; Alves, E.H.P.; Sales, A.C.S.; Rodrigues, R.R.L.; Galeno, J.G.; Gomes, T.N.; Ferreira, G.P.; Vasconcelos, D.F.P. Dengue Virus and Yellow Fever Virus Damage the Liver: A Systematic Review About the Histopathological Profiles. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Res. 2019, 8, 2864–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvelard, A.; Marianneau, P.; Bedel, C.; Drouet, M.T.; Vachon, F.; Hénin, D.; Deubel, V. Report of a fatal case of dengue infection with hepatitis: Demonstration of dengue antigens in hepatocytes and liver apoptosis. Hum. Pathol. 1999, 30, 1106–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, E.M. Dengue; Fiocruz: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2005; pp. 1–344. Available online: https://fiocruz.br/livro/dengue (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Bradham, C.A.; Qian, T.; Streetz, K.; Trautwein, C.; Brenner, D.A.; Lemasters, J.J. The Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Is Required for Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha-Mediated Apoptosis and Cytochrome c Release. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998, 18, 6353–6364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attisano, L.; Wrana, J.L. Signal Transduction by the TGF-β Superfamily. Science 2002, 296, 1646–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrana, J.L. Phosphoserine-Dependent Regulation of Protein-Protein Interactions in the Smad Pathway. Structure 2002, 10, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaresma, J.A.; Barros, V.L.; Pagliari, C.; Fernandes, E.R.; Guedes, F.; Takakura, C.F.; Andrade, H.F., Jr.; Vasconcelos, P.F.; Duarte, M.I. Revisiting the liver in human yellow fever: Virus-induced apoptosis in hepatocytes associated with TGF-β, TNF-α and NK cells activity. Virology 2006, 345, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.B.; Sierra, B.; Garcia, G.; Aguirre, E.; Babel, N.; Alvarez, M.; Sanchez, L.; Valdes, L.; Volk, H.D.; Guzman, M.G. Tumor necrosis factor–alpha, transforming growth factor–β1, and interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms: Implication in protection or susceptibility to dengue hemorrhagic fever. Hum. Immunol. 2010, 71, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.K.; Lichtman, A.H.; Pillai, S. Imunologia Celular e Molecular, 10th ed.; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2023; p. 672. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, N.S.O.; Romanos, M.T.V.; Wigg, M.D. Introdução à Virologia Humana, 2nd ed.; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2008; pp. 1–546. [Google Scholar]

- Castera, L.; Pawlotsky, J.-M. Noninvasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Medscape Gen. Med. 2005, 7, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Dev, A.; Patel, K.; McHutchison, J.G. Hepatitis C and steatosis. Clin. Liver Dis. 2004, 8, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, B.; Johnson, A.; Lewis, J.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walter, P. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th ed.; Garland Science: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 1–1616. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, O.M.; Barreto, D.F.; Paes, M.V.; Takiya, C.M.; Pinhão, A.T.; Schatzmayr, H.G. Morphological studies in a model for dengue-2 virus infection in mice. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2006, 101, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, T.; Tieu, N. The impact of dengue haemorrhagic fever on liver function. Res. Virol. 1997, 148, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, L.J.; Nogueira, R.M.R.; Soares, L.C.; Soares, C.E.C.; Ribas, B.F.; Alves, F.P.; Vieira, F.R.; Pessanha, F.E.B. The impact of dengue on liver function as evaluated by aminotransferase levels. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 11, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, D.D.; de Castro, A.R.C.M.; Froes, Í.B.; Bigaton, G.; de Oliveira, É.C.L.; Fabbro, M.F.J.D.; da Cunha, R.V.; da Costa, I.P. Clinical and laboratory findings in patients with dengue associated with hepatopathy. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2011, 44, 674–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.-H.; Tai, D.-I.; Chang-Chien, C.-S.; Lan, C.-K.; Chiou, S.-S.; Liaw, Y.-F. Liver Biochemical Tests and Dengue Fever. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1992, 47, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.K.; Gan, V.C.; Lee, V.J.; Tan, A.S.; Leo, Y.S.; Lye, D.C. Clinical relevance and discriminatory value of elevated liver ami-notransferase levels for dengue severity. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-J.; Wei, H.-X.; Jiang, S.-C.; He, C.; Xu, X.-J.; Peng, H.-J. Evaluation of aminotransferase abnormality in dengue patients: A meta analysis. Acta Trop. 2016, 156, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, R.A. Caracterização do Fenótipo da Resposta Inflamatória, da Expressão de Citocinas e do Mecanismo de Morte Celular no Fígado de Pacientes com Febre Hemorrágica da Dengue; Universidade de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jungermann, K.; Katz, N. Functional specialization of different hepatocyte populations. Physiol. Rev. 1989, 69, 708–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.R.; Thomsen, A.R.; Frevert, C.W.; Pham, U.; Skerrett, S.J.; Kiener, P.A.; Liles, W.C.; Park, D.R. Fas (CD95) Induces Proinflammatory Cytokine Responses by Human Monocytes and Monocyte-Derived Macrophages. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 6209–6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, R.J.; Barbet, G.; Bongers, G.; Hartmann, B.M.; Gettler, K.; Muniz, L.; Furtado, G.C.; Cho, J.; Lira, S.A.; Blander, J.M. Different tissue phagocytes sample apoptotic cells to direct distinct homeostasis programs. Nature 2016, 539, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, J.A.; Barros, V.L.; Pagliari, C.; Fernandes, E.R.; Andrade, H.F.; Vasconcelos, P.F.; Duarte, M.I. Hepatocyte lesions and cellular immune response in yellow fever infection. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007, 101, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, J.A.S.; Pagliari, C.; Medeiros, D.B.A.; Duarte, M.I.S.; Vasconcelos, P.F.C. Immunity and immune response, pathology and pathologic changes: Progress and challenges in the immunopathology of yellow fever. Rev. Med Virol. 2013, 23, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurane, I.; Kontny, U.; Janus, J.; Ennis, F.A. Dengue-2 virus infection of human mononuclear cell lines and establishment of persistent infections. Arch. Virol. 1990, 110, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-X.; Govindarajan, S.; Okamoto, S.; Dennert, G. NK Cells Cause Liver Injury and Facilitate the Induction of T Cell-Mediated Immunity to a Viral Liver Infection. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 6480–6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scroferneker, M.L.; Pohlmann, P.R. Imunologia: Básica e Aplicada; Sagra Luzzatto: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1998; pp. 1–571. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.-H.; Liu, C.-C.; Wang, S.-T.; Lei, H.-Y.; Liu, H.-S.; Lin, Y.-S.; Wu, H.-L.; Yeh, T.-M. Activation of coagulation and fibrinolysis during dengue virus infection. J. Med. Virol. 2001, 63, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Tang, Y.; Hu, F.; Zhou, W.; Yao, X.; Hong, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Tang, X.; Zhang, F. Serum levels of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecules may correlate with the severity of dengue virus-1 infection in adults. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2015, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blissard, G.W.; Wenz, J.R. Baculovirus gp64 Envelope Glycoprotein Is Sufficient To Mediate pH-Dependent Membrane Fusion. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 6829–6835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyoo, S.; Suttitheptumrong, A.; Pattanakitsakul, S.-N. Synergistic Effect of TNF-α and Dengue Virus Infection on Adhesion Molecule Reorganization in Human Endothelial Cells. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 70, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.D.; Yeh, W.T.; Yang, M.Y.; Chen, R.F.; Shaio, M.F. Antibody-dependent enhancement of heterotypic dengue infections involved in suppression of IFN-γ production. J. Med. Virol. 2001, 63, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Henriques, D.F.; Casseb, L.M.N.; Ferreira, M.S.; Freitas, L.S.; Fuzii, H.T.; Pagliari, C.; Kanashiro, L.; Castro, P.H.G.; Siva, G.A.; Amador Neto, O.P.; et al. Sequential Dengue Virus Infection in Marmosets: Histopathological and Immune Responses in the Liver. Viruses 2025, 17, 1619. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121619

Henriques DF, Casseb LMN, Ferreira MS, Freitas LS, Fuzii HT, Pagliari C, Kanashiro L, Castro PHG, Siva GA, Amador Neto OP, et al. Sequential Dengue Virus Infection in Marmosets: Histopathological and Immune Responses in the Liver. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1619. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121619

Chicago/Turabian StyleHenriques, Daniele Freitas, Livia M. N. Casseb, Milene S. Ferreira, Larissa S. Freitas, Hellen T. Fuzii, Carla Pagliari, Luciane Kanashiro, Paulo H. G. Castro, Gilmara A. Siva, Orlando Pereira Amador Neto, and et al. 2025. "Sequential Dengue Virus Infection in Marmosets: Histopathological and Immune Responses in the Liver" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1619. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121619

APA StyleHenriques, D. F., Casseb, L. M. N., Ferreira, M. S., Freitas, L. S., Fuzii, H. T., Pagliari, C., Kanashiro, L., Castro, P. H. G., Siva, G. A., Amador Neto, O. P., Campos, V. M., Belvis, B. C., dos Santos, F. B., de Sá, L. R. M., & Vasconcelos, P. F. d. C. (2025). Sequential Dengue Virus Infection in Marmosets: Histopathological and Immune Responses in the Liver. Viruses, 17(12), 1619. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121619