Diagnostic Accuracy of Next-Generation Sequencing: Prevalence of HIV-1 Drug Resistance and Associated Factors Among Adults on Integrase Inhibitors with Virologic Failure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

Data Collection

2.2. Laboratory Methods

2.2.1. RNA Extraction, Amplification, and Visualization

2.2.2. Sanger Sequencing

2.2.3. Next-Generation Sequencing

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Study Demographics, Medical History, and Clinical Characteristics

3.1.1. Socio Demographic Characteristics of Participants

3.1.2. Clinical and Medical History Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Diagnostic Accuracy of NGS

3.2.1. INSTI Major DRMs

3.2.2. INSTI Accessory Mutations

3.3. Prevalence of Drug Resistance Detected by NGS Among Adults Living with HIV on INSTIs with Virological Failure

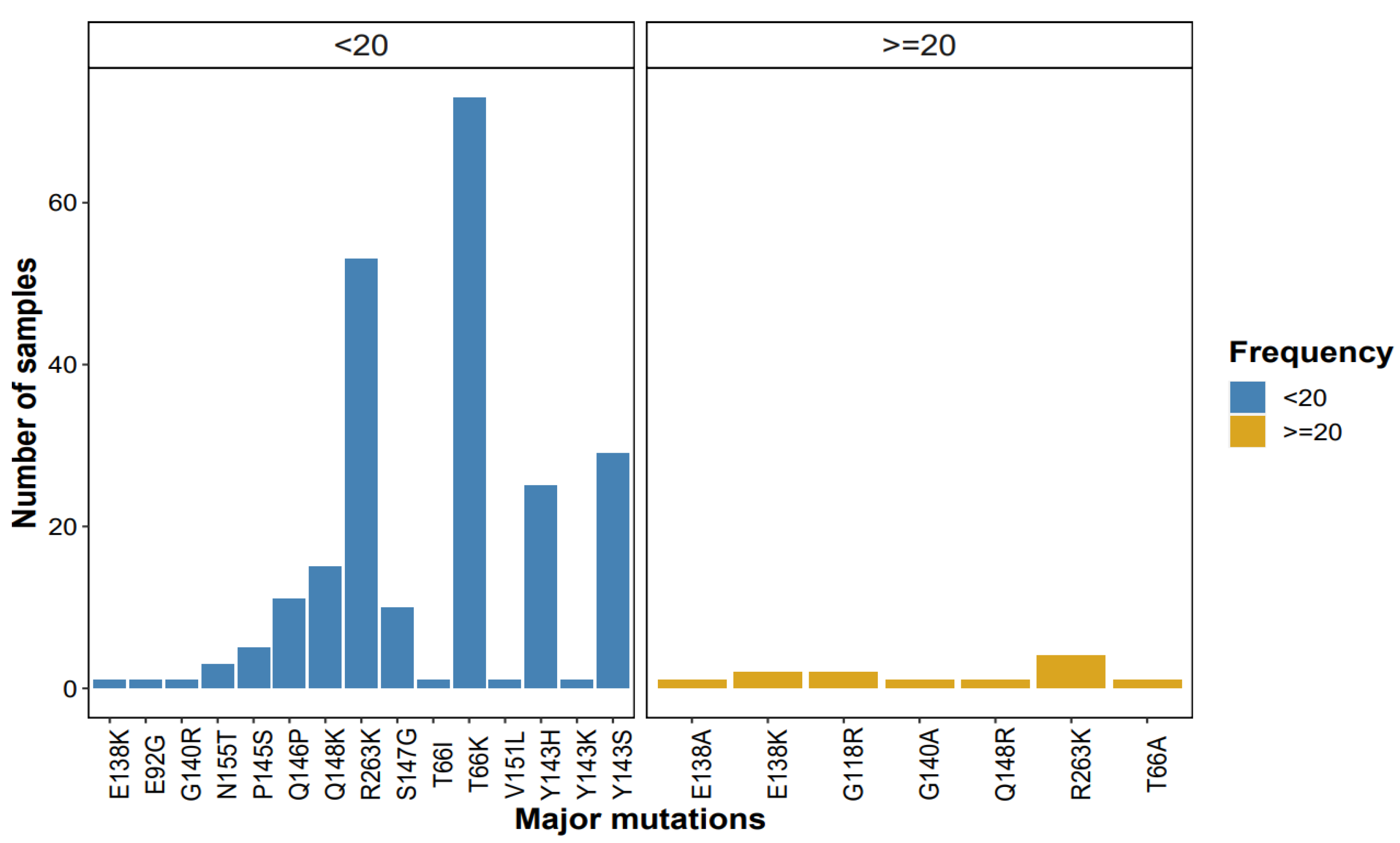

3.3.1. Patterns of Major Mutations Detected by NGS at ≥1% Threshold

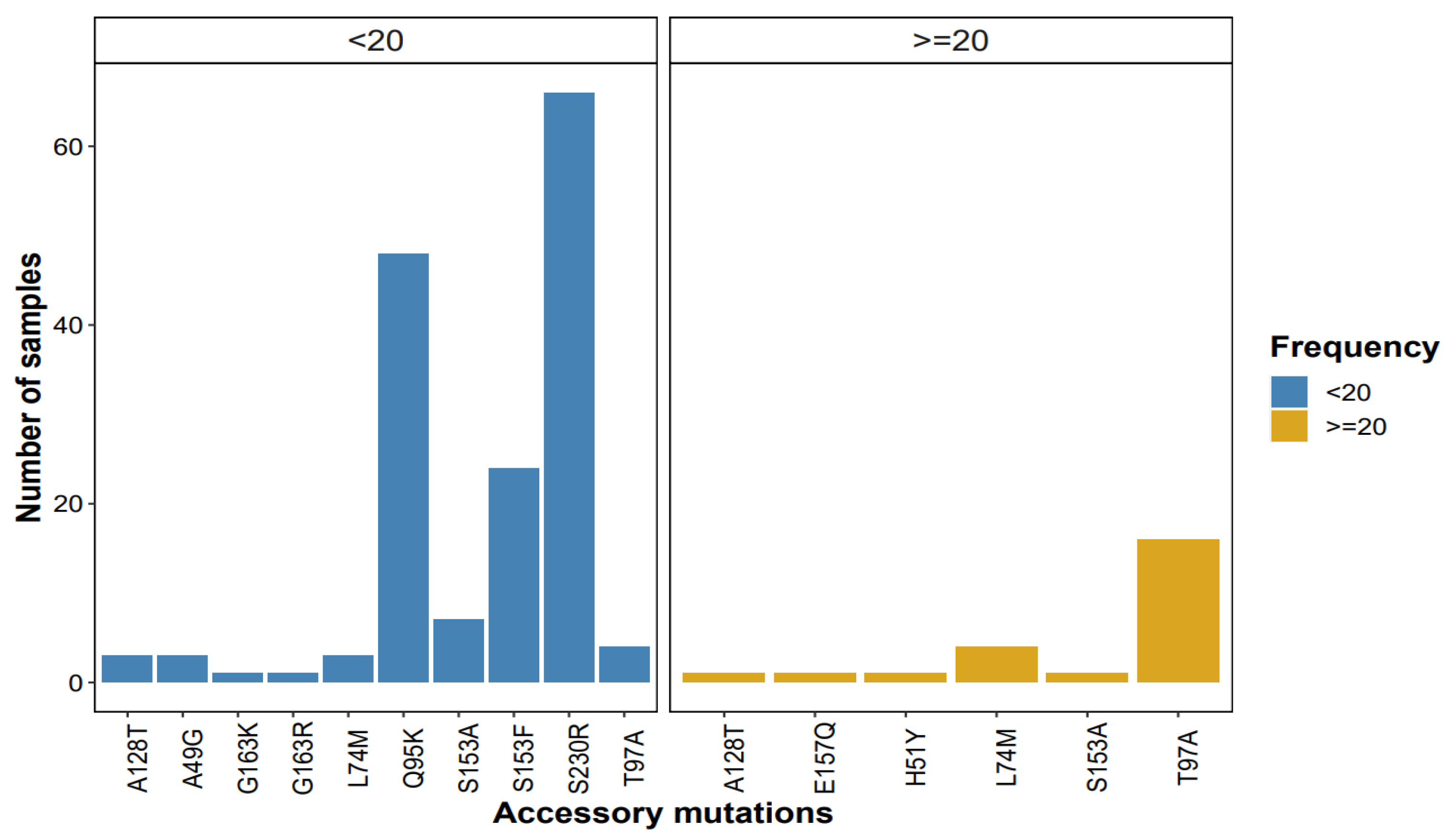

3.3.2. Patterns of Accessory Mutations Detected by NGS at ≥1% Threshold

3.4. Factors Associated with HIVDR Among Adults on INSTIs with Virologic Failure at UVRI

Bivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Presence of DRMs Among 175 Virologic Failures on INSTIs

4. Discussion

4.1. Diagnostic Accuracy of NGS Compared to Sanger Sequencing

4.2. Prevalence of DRMs Detected by NGS (≥20%) Among Adults on INSTIs with VF

4.3. Factors Associated with Drug Resistance Among PLHIV on INSTIs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. HIV and AIDS. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- WHO. HIV. August 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/hiv-aids/hiv-aids#:~:text=Globally%2C%2040.8%20million%20%5B37.0%E2%80%9345.6%20million%5D%20people%20were%20living,continues%20to%20vary%20considerably%20between%20countries%20and%20regions (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Ministry of Health (MOH), Uganda. Uganda Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment; Ministry of Health: Kampala, Uganda, 2020.

- UNAIDS. 2025 AIDS Targets. 2020. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/topics/2025_target_setting (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- WHO. HIV Drug Resistance. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-drug-resistance (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Ministry of Health (MOH), Uganda. Consolidated Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of HIV and AIDS in Uganda; Ministry of Health: Kampala, Uganda, 2018.

- Ministry of Health (MOH), Uganda. Uganda Announces Breakthrough HIV Prevention Injection with 100% Effectiveness; Ministry of Health: Kampala, Uganda, 2024.

- WHO. Transition to Dolutegravir-Based Antiretroviral Therapy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Inzaule, S.C.; Hamers, R.L.; Noguera-Julian, M.; Casadellà, M.; Parera, M.; Rinke de Wit, T.F.; Paredes, R. Primary resistance to integrase strand transfer inhibitors in patients infected with diverse HIV-1 subtypes in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1167–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watera, C.; Ssemwanga, D.; Namayanja, G.; Asio, J.; Lutalo, T.; Namale, A.; Sanyu, G.; Ssewanyana, I.; Gonzalez-Salazar, J.F.; Nazziwa, J. HIV drug resistance among adults initiating antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 2407–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoufaly, A.; Kraft, C.; Schmidbauer, C.; Puchhammer-Stoeckl, E. Prevalence of integrase inhibitor resistance mutations in Austrian patients recently diagnosed with HIV from 2008 to 2013. Infection 2017, 45, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lepik, K.J.; Harrigan, P.R.; Yip, B.; Wang, L.; Robbins, M.A.; Zhang, W.W.; Toy, J.; Akagi, L.; Lima, V.D.; Guillemi, S. Emergent drug resistance with integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based regimens. Aids 2017, 31, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndashimye, E.; Avino, M.; Olabode, A.S.; Poon, A.F.; Gibson, R.M.; Li, Y.; Meadows, A.; Tan, C.; Reyes, P.S.; Kityo, C.M. Accumulation of integrase strand transfer inhibitor resistance mutations confers high-level resistance to dolutegravir in non-B subtype HIV-1 strains from patients failing raltegravir in Uganda. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3525–3533. [Google Scholar]

- Northrop, A.J.; Pomeroy, L.W. Forecasting prevalence of HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) drug resistance: A modeling study. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2020, 83, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidjinou, E.K.; Deldalle, J.; Hallaert, C.; Robineau, O.; Ajana, F.; Choisy, P.; Hober, D.; Bocket, L. RNA and DNA Sanger sequencing versus next-generation sequencing for HIV-1 drug resistance testing in treatment-naive patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2823–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.R.; Gao, F.; Sandstrom, P.; Ji, H. External quality assessment for next-generation sequencing-based HIV drug resistance testing: Unique requirements and challenges. Viruses 2020, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, C.K.; Brumme, C.J.; Liu, T.F.; Chui, C.K.; Chu, A.L.; Wynhoven, B.; Hall, T.A.; Trevino, C.; Shafer, R.W.; Harrigan, P.R. Automating HIV drug resistance genotyping with RECall, a freely accessible sequence analysis tool. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 1936–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illumina. Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit Reference Guide; Illumina Proprietary Part# 15031942v03; Illumina: Cambridgeshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Parkin, N.; Avila-Rios, S.; Bibby, D.; Brumme, C.; Eshleman, S.; Harrigan, P.; Howison, M.; Hunt, G.; Ji, H.; Kantor, R. Multi-Laboratory Comparison of Next-Generation to Sanger-Based Sequencing for HIV-1 Drug Resistance Genotyping. Viruses 2020, 12, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.R.; Parkin, N.; Jennings, C.; Brumme, C.J.; Enns, E.; Casadellà, M.; Howison, M.; Coetzer, M.; Avila-Rios, S.; Capina, R. Performance comparison of next generation sequencing analysis pipelines for HIV-1 drug resistance testing. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.; López, P.; Sánchez, R.; Yamamura, Y.; Rivera-Amill, V. Sanger and next generation sequencing approaches to evaluate HIV-1 virus in blood compartments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 1697. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Cai, Y.; Shi, T.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Yang, B.; Zhang, W.; Guan, Z. Detecting the presence of bacteria in low-volume preoperative aspirated synovial fluid by metagenomic next-generation sequencing. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 99, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanfack, A.J.; Redd, A.D.; Bimela, J.S.; Ncham, G.; Achem, E.; Banin, A.N.; Kirkpatrick, A.R.; Porcella, S.F.; Agyingi, L.A.; Meli, J. Multimethod longitudinal HIV drug resistance analysis in antiretroviral-therapy-naive patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 2785–2800. [Google Scholar]

- Mahase, E. HIV: WHO reports “worrying” increase in resistance to key antiretroviral treatment. BMJ 2024, 384, q573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayitewala, A.; Ssewanyana, I.; Kiyaga, C. Next generation sequencing based in-house HIV genotyping method: Validation report. AIDS Res. Ther. 2021, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.M.; Schmotzer, C.L.; Quiñones-Mateu, M.E. Next-generation sequencing to help monitor patients infected with HIV: Ready for clinical use? Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2014, 16, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.-Y.; Lin, P.-H.; Cheng, C.-L.; Chen, M.-Y.; Sun, H.-Y.; Hsieh, S.-M.; Sheng, W.-H.; Su, Y.-C.; Su, L.-H.; Chang, S.-F. Prevalence of integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTI) resistance mutations in Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJesus, E.; Rockstroh, J.K.; Henry, K.; Molina, J.-M.; Gathe, J.; Ramanathan, S.; Wei, X.; Yale, K.; Szwarcberg, J.; White, K. Co-formulated elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus co-formulated emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: A randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2012, 379, 2429–2438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hurt, C.B.; Sebastian, J.; Hicks, C.B.; Eron, J.J. Resistance to HIV integrase strand transfer inhibitors among clinical specimens in the United States, 2009–2012. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyeyune, F.; Gibson, R.M.; Nankya, I.; Venner, C.; Metha, S.; Akao, J.; Ndashimye, E.; Kityo, C.M.; Salata, R.A.; Mugyenyi, P. Low-frequency drug resistance in HIV-infected Ugandans on antiretroviral treatment is associated with regimen failure. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 3380–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Tao, K.; Kouamou, V.; Avalos, A.; Scott, J.; Grant, P.M.; Rhee, S.-Y.; McCluskey, S.M.; Jordan, M.R.; Morgan, R.L.; et al. Prevalence of Emergent Dolutegravir Resistance Mutations in People Living with HIV: A Rapid Scoping Review. Viruses 2024, 16, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiang, M.; Jones, G.S.; Goldsmith, J.; Mulato, A.; Hansen, D.; Kan, E.; Tsai, L.; Bam, R.A.; Stepan, G.; Stray, K.M. Antiviral activity of bictegravir (GS-9883), a novel potent HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitor with an improved resistance profile. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 7086–7097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S.-Y.; Grant, P.M.; Tzou, P.L.; Barrow, G.; Harrigan, P.R.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Shafer, R.W. A systematic review of the genetic mechanisms of dolutegravir resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 3135–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavro, C.; Ruel, T.; Wiznia, A.; Montañez, N.; Nangle, K.; Horton, J.; Buchanan, A.M.; Stewart, E.L.; Palumbo, P. Emergence of resistance in HIV-1 integrase with dolutegravir treatment in a pediatric population from the IMPAACT P1093 study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e01645-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Yoshinaga, T.; Seki, T.; Wakasa-Morimoto, C.; Brown, K.W.; Ferris, R.; Foster, S.A.; Hazen, R.J.; Miki, S.; Suyama-Kagitani, A. In vitro antiretroviral properties of S/GSK1349572, a next-generation HIV integrase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.-Y.; Parkin, N.; Harrigan, P.R.; Holmes, S.; Shafer, R.W. Genotypic correlates of resistance to the HIV-1 strand transfer integrase inhibitor cabotegravir. Antivir. Res. 2022, 208, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.W.; Cheung, P.K.; Oliveira, N.; Robbins, M.A.; Harrigan, P.R.; Shahid, A. Accumulation of multiple mutations in vivo confers cross-resistance to new and existing integrase inhibitors. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 1773–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladini, F.; Giannini, A.; Boccuto, A.; Tiezzi, D.; Vicenti, I.; Zazzi, M. The HIV-1 integrase E157Q polymorphism per se does not alter susceptibility to raltegravir and dolutegravir in vitro. AIDS 2017, 31, 2307–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Z.; Kuritzkes, D.R. Clinical implications of HIV-1 minority variants. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Stella-Ascariz, N.; Arribas, J.R.; Paredes, R.; Li, J.Z. The role of HIV-1 drug-resistant minority variants in treatment failure. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, S847–S850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F.; Yuan, D.; Zhai, W.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, H. HIV-1 Drug Resistance Detected by Next-Generation Sequencing among ART-Naïve Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Viruses 2024, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Ríos, S.; Parkin, N.; Swanstrom, R.; Paredes, R.; Shafer, R.; Ji, H.; Kantor, R. Next-generation sequencing for HIV drug resistance testing: Laboratory, clinical, and implementation considerations. Viruses 2020, 12, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Target Product Profile for HIV Drug Resistance Tests in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Africa; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Women and Girls Carry the Heaviest HIV Burden in Sub-Saharan Africa; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tsikhutsu, I.; Bii, M.; Dear, N.; Ganesan, K.; Kasembeli, A.; Sing’oei, V.; Rombosia, K.; Ochieng, C.; Desai, P.; Wolfman, V. Prevalence and correlates of viral load suppression and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) drug resistance among children and adolescents in south rift valley and Kisumu, Kenya. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Shang, M.; Yang, W.; Wang, Z.; Shang, H. Research on the treatment effects and drug resistances of long-term second-line antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patients from Henan Province in China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scriven, Y.A.; Mulinge, M.M.; Saleri, N.; Luvai, E.A.; Nyachieo, A.; Maina, E.N.; Mwau, M. Prevalence and factors associated with HIV-1 drug resistance mutations in treatment-experienced patients in Nairobi, Kenya: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 2021, 100, e27460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayitewala, A.; Kyeyune, F.; Ainembabazi, P.; Nabulime, E.; Kato, C.D.; Nankya, I. Comparison of HIV drug resistance profiles across HIV-1 subtypes A and D for patients receiving a tenofovir-based and zidovudine-based first line regimens in Uganda. AIDS Res. Ther. 2020, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wainberg, M.A. HIV-1 subtype distribution and the problem of drug resistance. Aids 2004, 18, S63–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Median (Q1, Q3) | All n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 105 (60.0) | |

| Male | 70 (40.0) | ||

| Age | 36 (27, 46) | ||

| Health facility | HCII | 3 (1.7) | |

| HCIII | 49 (28.0) | ||

| HCIV | 33 (18.9) | ||

| General hospital | 30 (17.1) | ||

| Regional referral | 29 (16.6) | ||

| Other | 31 (17.7) | ||

| Region | Central | 54 (30.9) | |

| Northern | 59 (33.7) | ||

| Eastern | 26 (14.9) | ||

| Western | 36 (20.6) |

| Variable | Category | Median (IQR) | All n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration on ART in year(s) | 1–2 | 68 (38.9) | |

| 2–5 | 45 (25.7) | ||

| >5 | 62 (35.4) | ||

| Duration on INSTIs in year(s) | 1 | 41 (23.4) | |

| 2 | 82 (46.9) | ||

| 3 | 36 (20.6) | ||

| 4 | 16 (9.1) | ||

| Current ART regimen | TDF/3TC/DTG | 170 (97.1) | |

| ABC/3TC/DTG | 4 (2.3) | ||

| AZT/3TC/DTG | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Log10Viral load copies/mL | 4.248 (3.568, 4.959) | ||

| HIV subtype | A1 | 121 (69.1) | |

| D | 46 (26.3) | ||

| C | 6 (3.4) | ||

| B | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Unique recombinant | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Adherence | Good >95% | 116 (66.3) | |

| unknown | 59 (33.7) |

| Sanger Sequencing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGS (≥20%) | Positive | Negative | ||

| positive | 7 | 0 | 7 | |

| negative | 0 | 168 | 168 | |

| total | 7 | 168 | 175 | |

| Proportion (%) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | 4% | 1.6–8.1 |

| Sensitivity | 100% | 59.0–100 |

| Specificity | 100% | 97.8–100 |

| Positive Predictive Value | 100% | 59.0–100 |

| Negative Predictive Value | 100% | 97.8–100 |

| Overall Accuracy | 100% | |

| Positive Likelihood Ratio | N.S | |

| Negative Likelihood Ratio | 0 |

| Sanger Sequencing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGS (≥20%) | Positive | Negative | ||

| positive | 24 | 6 | 30 | |

| negative | 0 | 145 | 145 | |

| total | 24 | 151 | 175 | |

| Proportion (%) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | 17.10% | 11.9–23.6% |

| Sensitivity | 80.00% | 61.4–92.3% |

| Specificity | 100.00% | 97.5–100.0% |

| Positive Predictive Value | 100.00% | 85.8–100.0% |

| Negative Predictive Value | 96.00% | 91.6–98.5% |

| Overall Accuracy | 96.60% | |

| Positive Likelihood Ratio | N.S | |

| Negative Likelihood Ratio | 0.2 | 0.10–0.41 |

| NGS Threshold | N (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| ≥20% | 7 (4.0) | 1.6–8.0 |

| ≥10% | 14 (8.0) | 4.4–13.1 |

| ≥5% | 32 (18.3) | 12.9–24.8 |

| ≥2% | 94 (53.7) | 46.0–61.3 |

| ≥1% | 105 (60.0) | 53.1–67.6 |

| Variable | DRMs | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 3 (2.9) | 102 (97.1) | Reference | ||

| Male | 4 (5.7) | 66 (94.3) | 2.061 | 0.447–9.503 | 0.354 |

| Age | |||||

| 18–26 | 1 (2.9) | 33 (97.1) | Reference | ||

| 27–44 | 3 (3.2) | 92 (96.8) | 1.076 | 0.108–10.710 | 0.950 |

| ≥45 | 3 (6.5) | 43 (93.5) | 2.302 | 0.228–23.152 | 0.479 |

| Health facility | |||||

| Health center * | 5 (5.9) | 80 (94.1) | Reference | ||

| Hospital * | 1 (1.7) | 58 (98.3) | 0.276 | 0.031–2.424 | 0.246 |

| TASO | 1 (3.2) | 30 (96.8) | 0.533 | 0.059–4.754 | 0.573 |

| Region | |||||

| Central | 1 (1.9) | 53 (98.1) | 0.259 | 0.028–2.397 | 0.234 |

| Northern | 4 (6.8) | 55 (93.2) | Reference | ||

| Eastern | 1 (3.8) | 25 (96.2) | 0.550 | 0.058–5.175 | 0.601 |

| Western | 1 (2.8) | 35 (97.2) | 0.393 | 0.042–3.660 | 0.412 |

| Duration on ART in year(s) | |||||

| 1–2 | 1 (1.5) | 67 (98.5) | Reference | ||

| 2–5 | 3 (6.7) | 42 (93.3) | 4.785 | 0.481–47.534 | 0.181 |

| >5 | 3 (4.8) | 59 (95.2) | 3.406 | 0.345–33.644 | 0.294 |

| Duration on INSTIs in year(s) | |||||

| 1–2 | 4 (3.4) | 133 (96.6) | Reference | ||

| >2 | 3 (5.17) | 55 (94.8) | 1.541 | 0.333–7.125 | 0.580 |

| Viral load | 0.643 | 0.233–1.774 | 0.394 | ||

| HIV subtype | |||||

| A1 | 5 (4.1) | 116 (95.9) | Reference | ||

| Others * | 2 (3.7) | 52 (96.3) | 0.892 | 0.168–4.750 | 0.894 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lunkuse, S.; Kiiza, R.; Ssekagiri, A.; Nannyonjo, M.; Ntenkaire, N.; Nassolo, F.; Namagembe, H.S.; Kiberu, F.; Kabuuka, D.; Andia, I.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Next-Generation Sequencing: Prevalence of HIV-1 Drug Resistance and Associated Factors Among Adults on Integrase Inhibitors with Virologic Failure. Viruses 2025, 17, 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121596

Lunkuse S, Kiiza R, Ssekagiri A, Nannyonjo M, Ntenkaire N, Nassolo F, Namagembe HS, Kiberu F, Kabuuka D, Andia I, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Next-Generation Sequencing: Prevalence of HIV-1 Drug Resistance and Associated Factors Among Adults on Integrase Inhibitors with Virologic Failure. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121596

Chicago/Turabian StyleLunkuse, Sandra, Ronald Kiiza, Alfred Ssekagiri, Maria Nannyonjo, Nathan Ntenkaire, Faridah Nassolo, Hamida Suubi Namagembe, Faizo Kiberu, Danstan Kabuuka, Irene Andia, and et al. 2025. "Diagnostic Accuracy of Next-Generation Sequencing: Prevalence of HIV-1 Drug Resistance and Associated Factors Among Adults on Integrase Inhibitors with Virologic Failure" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121596

APA StyleLunkuse, S., Kiiza, R., Ssekagiri, A., Nannyonjo, M., Ntenkaire, N., Nassolo, F., Namagembe, H. S., Kiberu, F., Kabuuka, D., Andia, I., Kalyango, J. N., Kibwika, P. B., Bbosa, N., Kaleebu, P., & Ssemwanga, D. (2025). Diagnostic Accuracy of Next-Generation Sequencing: Prevalence of HIV-1 Drug Resistance and Associated Factors Among Adults on Integrase Inhibitors with Virologic Failure. Viruses, 17(12), 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121596