In Vitro Evaluation of the Antiviral Effect of Spirulina maxima (Arthrospira) Alga Against Chikungunya Virus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Spirulina maxima (Arthospira) Used in the Tests

2.2. Preparation of Spirulina maxima (Arthospira) Extracts

2.3. Chemical Composition of SP Methanol Extract (SP-M)

2.4. Cell Lines

2.5. Virus Stock

2.6. Evaluation of the Cytotoxic Activity of Spirulina maxima (Arthospira) Extracts

2.7. Anti-CHIKV Activity

2.7.1. Evaluation of the Extracts

2.7.2. Time of Addition Assay

2.7.3. Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

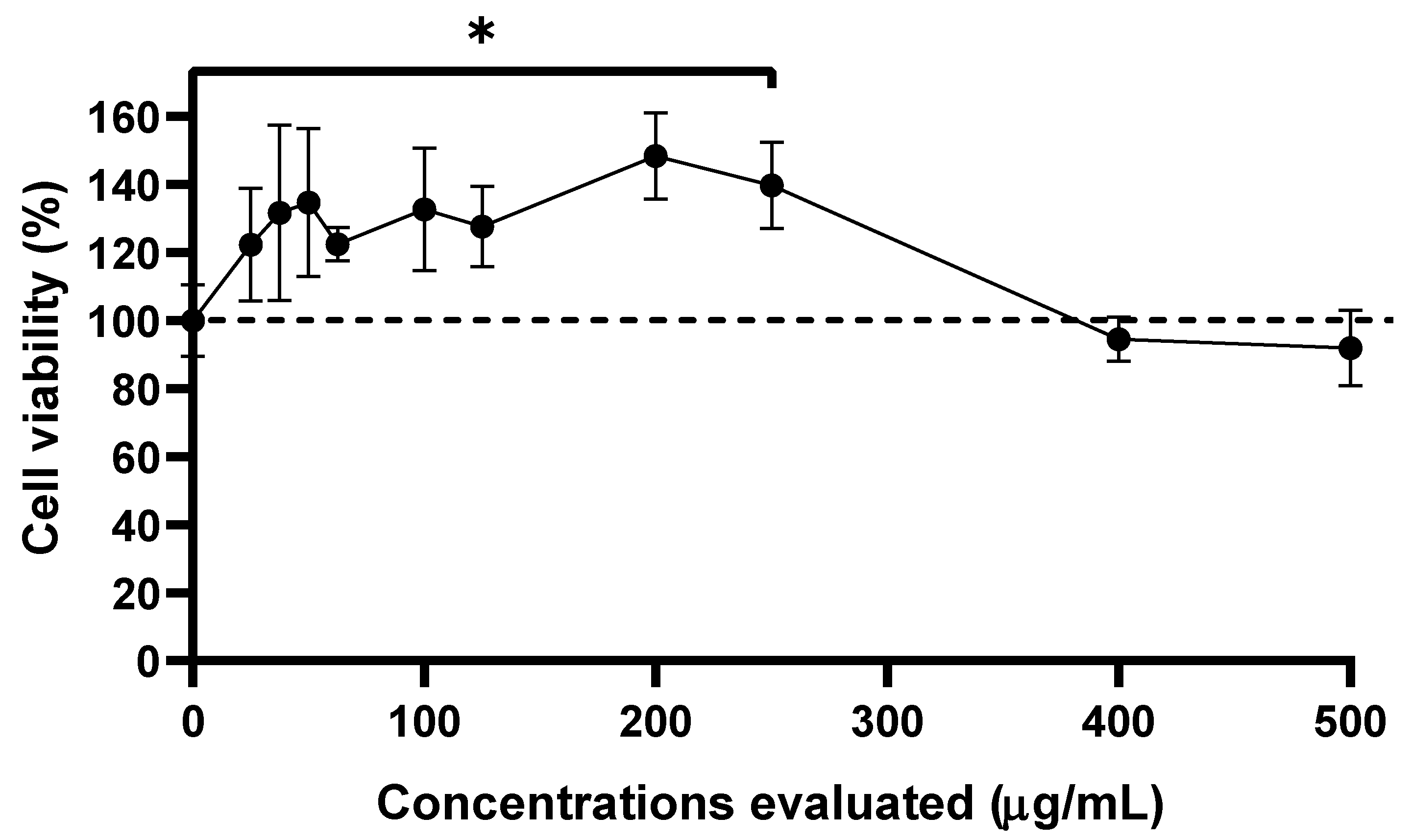

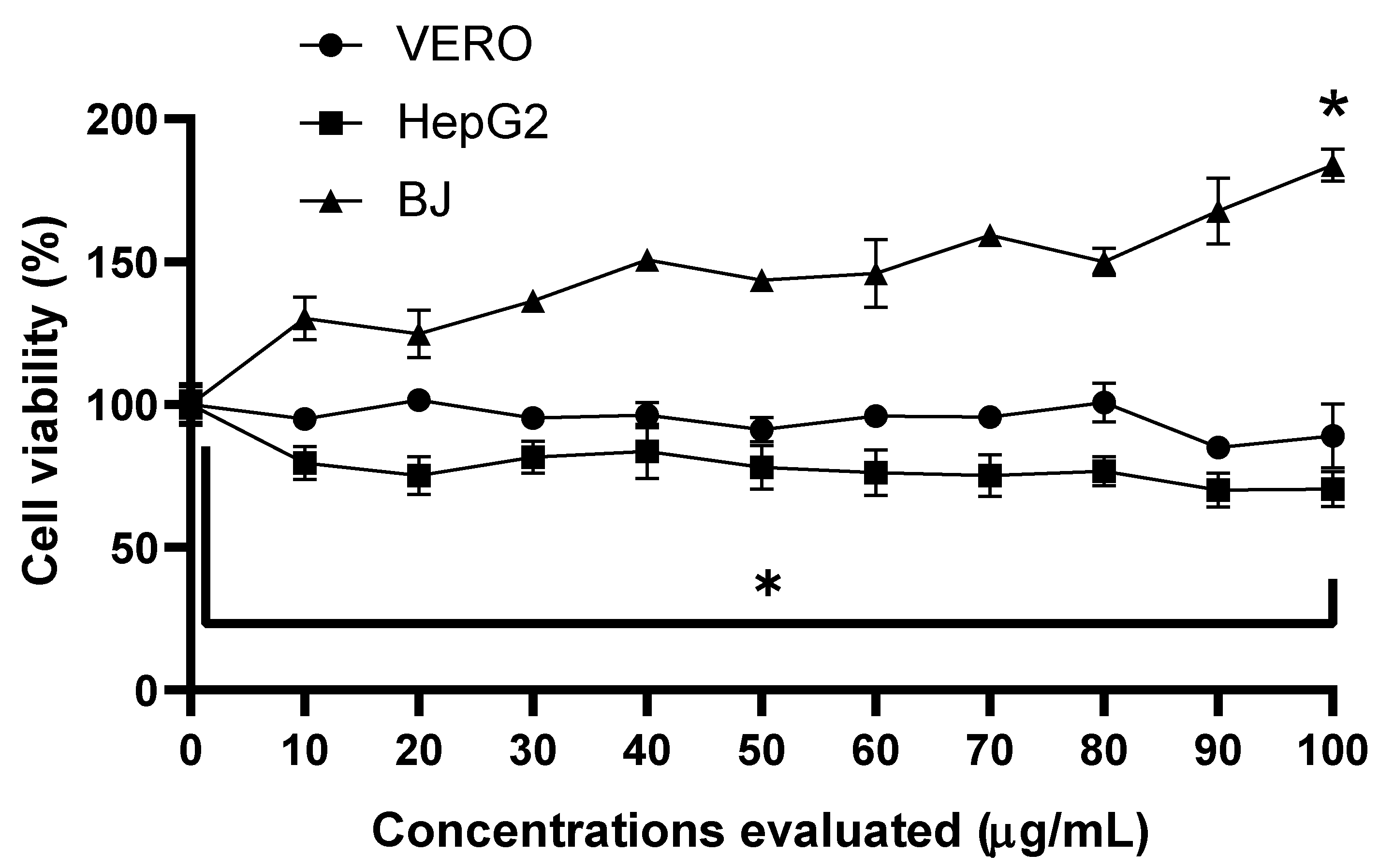

3.1. Cell Viability and Cytotoxicity Assay of Extracts

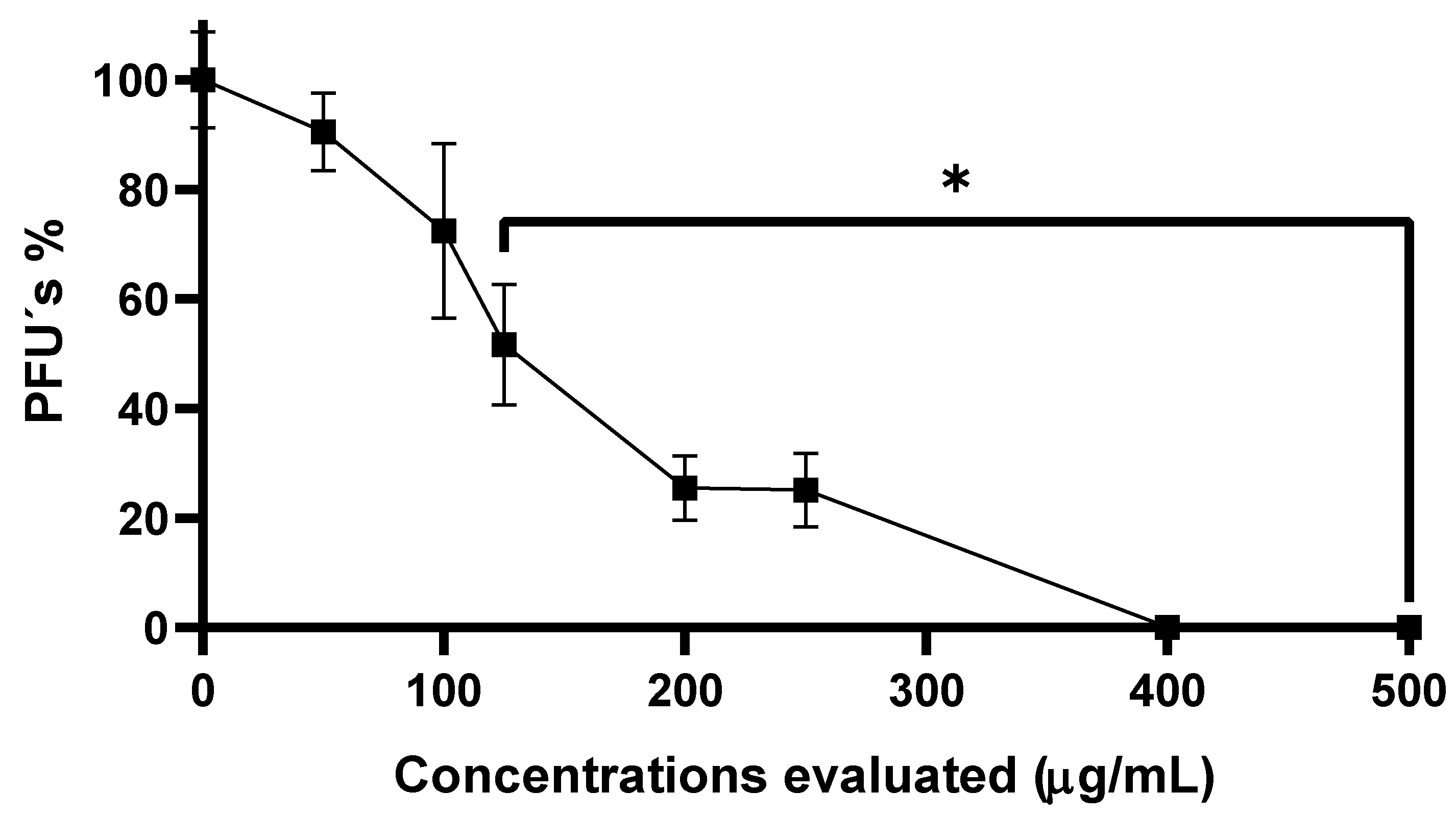

3.2. Anti-CHIKV Activity of SP-W

3.3. Evaluation of Anti-CHIKV Activity of Three Extracts Obtained from SP Powder

3.4. Anti-CHIKV Activity of Methanolic Extract from SP Powder

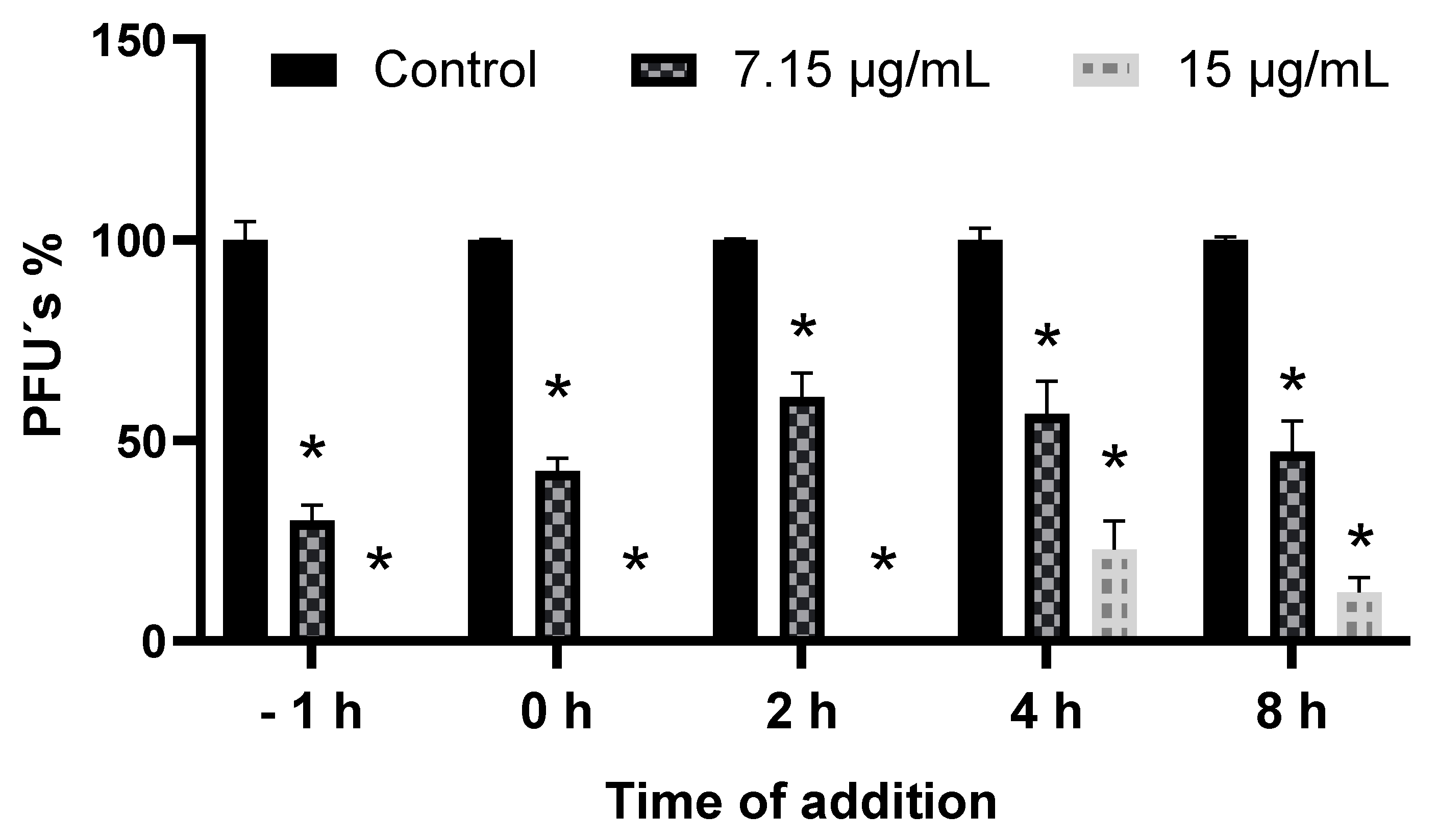

3.5. Addition Time Assay of SP-W

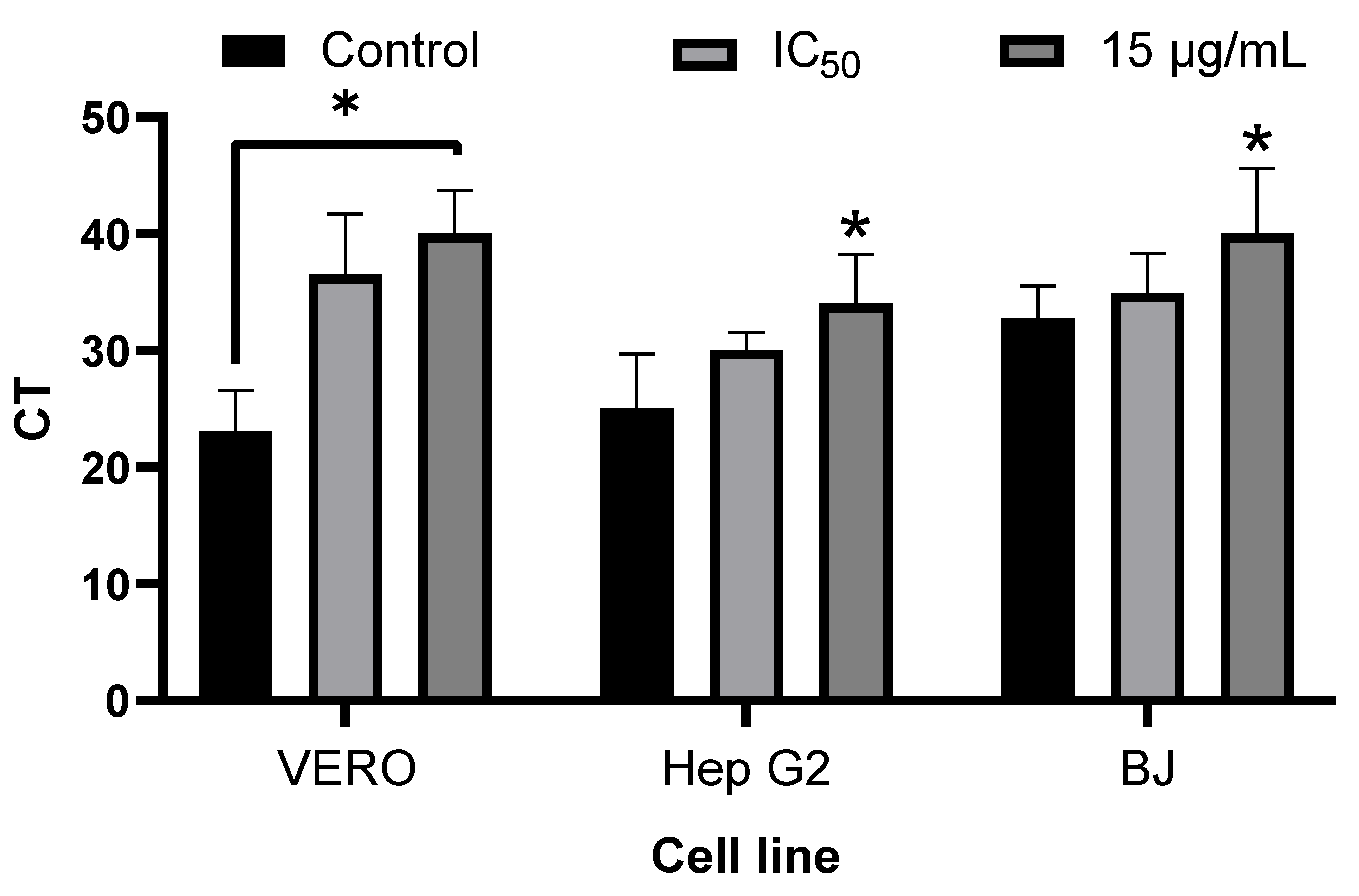

3.6. Inhibition of Viral Replication by Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

3.7. Chemical Composition of SP-M

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ganesan, V.K.; Duan, B.; Reid, S.P. Chikungunya Virus: Pathophysiology, Mechanism, and Modeling. Viruses 2017, 9, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khongwichit, S.; Chansaenroj, J.; Chirathaworn, C.; Poovorawan, Y. Chikungunya virus infection: Molecular biology, clinical characteristics, and epidemiology in Asian countries. J. Biomed. Sci. 2021, 28, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bettis, A.A.; L’Azou Jackson, M.; Yoon, I.K.; Breugelmans, J.G.; Goios, A.; Gubler, D.J.; Powers, A.M. The global epidemiology of chikungunya from 1999 to 2020: A systematic literature review to inform the development and introduction of vaccines. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pan American Health Organization. PLISA Health Information Platform for the Americas, Chikungunya Indicators Portal; PAHO/WHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/chikungunya (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Chikungunya Worldwide Overview. 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/chikungunya-virus-disease/surveillance-and-updates/seasonal-surveillance (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Borgherini, G.; Poubeau, P.; Jossaume, A.; Gouix, A.; Cotte, L.; Michault, A.; Arvin-Berod, C.; Paganin, F. Persistent arthralgia asso-ciated with chikungunya virus: A study of 88 adult patients on reunion island. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 47, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goupil, B.A.; Mores, C.N. A Review of Chikungunya Virus-induced Arthralgia: Clinical Manifestations, Therapeutics, and Pathogenesis. Open Rheumatol. J. 2016, 10, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bartholomeeusen, K.; Daniel, M.; LaBeaud, D.A.; Gasque, P.; Peeling, R.W.; Stephenson, K.E.; Ng, L.F.P.; Ariën, K.K. Chikungunya fever. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 17, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-023-00442-5Erratum in Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 26.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cerny, T.; Schwarz, M.; Schwarz, U.; Lemant, J.; Gérardin, P.; Keller, E. The Range of Neurological Complications in Chikungunya Fever. Neurocrit Care 2017, 27, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaid, A.; Gérardin, P.; Taylor, A.; Mostafavi, H.; Malvy, D.; Mahalingam, S. Chikungunya Arthritis: Implications of Acute and Chronic Inflammation Mechanisms on Disease Management. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 70, 484–495, https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40719Erratum in Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018, 70, 1596.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, A.M. Vaccine and Therapeutic Options to Control Chikungunya Virus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31, e00104-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- CEPI Priority Diseases. 2024. Available online: https://cepi.net/priority-pathogens (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Mehand, M.S.; Al-Shorbaji, F.; Millett, P.; Murgue, B. The WHO R&D Blueprint: 2018 review of emerging infectious diseases requiring urgent research and development efforts. Antivir. Res. 2018, 159, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghildiyal, R.; Gabrani, R. Antiviral therapeutics for chikungunya virus. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2020, 30, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasabe, B.; Ahire, G.; Patil, P.; Punekar, M.; Davuluri, K.S.; Kakade, M.; Alagarasu, K.; Parashar, D.; Cherian, S. Drug repurposing approach against chikungunya virus: An in vitro and in silico study. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1132538, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1226054Erratum in Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1226054.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jeengar, M.K.; Kurakula, M.; Patil, P.; More, A.; Sistla, R.; Parashar, D. Antiviral activity of stearylamine against chikungunya virus. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2021, 235, 105049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.F.; Teixeira, R.R.; Oliveira, A.S.; Souza, A.P.; Silva, M.L.; Paula, S.O. Potential Antivirals: Natural Products Targeting Rep-lication Enzymes of Dengue and Chikungunya Viruses. Molecules 2017, 22, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martins, D.O.S.; Santos, I.A.; de Oliveira, D.M.; Grosche, V.R.; Jardim, A.C.G. Antivirals against Chikungunya Virus: Is the Solution in Nature? Viruses 2020, 12, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jakubiec-Krzesniak, K.; Rajnisz-Mateusiak, A.; Guspiel, A.; Ziemska, J.; Solecka, J. Secondary Metabolites of Actinomycetes and their Antibacterial, Antifungal and Antiviral Properties. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zulkifli, N.; Khairat, J.E.; Azman, A.S.; Baharudin, N.M.; Malek, N.A.; Zainal Abidin, S.A.; AbuBakar, S.; Hassandarvish, P. Antiviral Activities of Streptomyces KSF 103 Methanolic Extracts against Dengue Virus Type-2. Viruses 2023, 15, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- da Silva, M.B.F.; Teixeira, C.M.L.L. Cyanobacterial and microalgae polymers: Antiviral activity and applications. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 3287–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vasilakis, G.; Marka, S.; Ntzouvaras, A.; Zografaki, M.E.; Kyriakopoulou, E.; Kalliampakou, K.I.; Bekiaris, G.; Korakidis, E.; Papageor-giou, N.; Christofi, S.; et al. Wound Healing, Antioxidant, and Antiviral Properties of Bioactive Polysaccharides of Microalgae Strains Isolated from Greek Coastal Lagoons. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Geetha Bai, R.; Tuvikene, R. Potential Antiviral Properties of Industrially Important Marine Algal Polysaccharides and Their Significance in Fighting a Future Viral Pandemic. Viruses 2021, 13, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Priyanka, S.; Varsha, R.; Riya Verma Ayenampudi, S.B. Spirulina: A spotlight on its nutraceutical properties and food pro-cessing applications. J. Microb. Biotech. Food Sci. 2023, 12, e4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Juárez, A.; Aguilar-Faisal, J.L.; Posadas-Mondragón, A.; Santiago-Cruz, J.A.; Barrientos-Alvarado, C.; Mojica-Villegas, M.A.; Chamorro-Cevallos, G.A.; Morales-González, J.A. Effect of Spirulina (Formerly arthrospira) maxima against Ethanol-Induced Damage in Rat Liver. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Moneim, A.E.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Shehata, A.M.; Saad, A.M.; Aldhumri, S.A.; Ouda, S.M.; Mesalam, N.M. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Spirulina platensis extracts and biogenic selenium nanoparticles against selected pathogenic bac-teria and fungi. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 29, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, R.; Foroughinia, F.; Dadbakhsh, A.H.; Afsari, F.; Zarshenas, M.M. An Overview of Pharmacological and Clinical Aspects of Spirulina. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2023, 20, e291122211363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuhu, A. Spirulina (Arthrospira): An Important Source of Nutritional and Medicinal Compounds. J. Mar. Biol. 2013, 2013, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Chang, G.K.; Kuo, S.M.; Huang, S.Y.; Hu, I.C.; Lo, Y.L.; Shih, S.R. Well-tolerated Spirulina extract inhibits influenza virus replication and reduces virus-induced mortality. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rechter, S.; König, T.; Auerochs, S.; Thulke, S.; Walter, H.; Dörnenburg, H.; Walter, C.; Marschall, M. Antiviral activity of Arthrospira-derived spirulan-like substances. Antivir. Res. 2006, 72, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghasadeghi, M.R.; Zaheri Birgani, M.A.; Jamalimoghadamsiyahkali, S.; Hosamirudsari, H.; Moradi, A.; Jafari-Sabet, M.; Sadigh, N.; Rahimi, P.; Tavakoli, R.; Hamidi-Fard, M.; et al. Effect of high-dose Spirulina supplementation on hospitalized adults with COVID-19: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1332425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santiago-Cruz, J.A.; Posadas-Mondragón, A.; Pérez-Juárez, A.; Herrera-González, N.E.; Chin-Chan, J.M.; Aguilar-González, J.E.; Aguilar-Faisal, J.L. In vitro Evaluation of the Anti-Chikungunya Virus Activity of an Active Fraction Obtained from Euphorbia grandicornis Latex. Viruses 2024, 16, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abd El-Baky, H.H.; El-Baroty, G.S. Spirulina maxima L-asparaginase: Immobilization, Antiviral and Antiproliferation Activities. Recent. Pat. Biotechnol. 2020, 14, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Castro, A.J.; Villarreal, M.L.; Salazar-Olivo, L.A.; Gomez-Sanchez, M.; Dominguez, F.; Garcia-Carranca, A. Mexican medicinal plants used for cancer treatment: Pharmacological, phytochemical and ethnobotanical studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 945–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.H.; Ahn, J.; Kang, D.H.; Lee, H.Y. The effect of ultrasonificated extracts of Spirulina maxima on the anticancer activity. Mar. Biotechnol. 2011, 13, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wai, T.; Langer, T. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Metabolic Regulation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 27, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Dial, S.; Shi, L.; Branham, W.; Liu, J.; Fang, J.L.; Green, B.; Deng, H.; Kaput, J.; Ning, B. Similarities and differences in the ex-pression of drug-metabolizing enzymes between human hepatic cell lines and primary human hepatocytes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011, 39, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Talbott, H.E.; Mascharak, S.; Griffin, M.; Wan, D.C.; Longaker, M.T. Wound healing, fibroblast heterogeneity, and fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 1161–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Salama, N.N.; Fasano, A.; Thakar, M.; Eddington, N.D. The impact of DeltaG on the oral bioavailability of low bioavailable ther-apeutic agents. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 312, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufek, M.B.; Bridges, A.S.; Thakker, D.R. Intestinal first-pass metabolism by cytochrome p450 and not p-glycoprotein is the major barrier to amprenavir absorption. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2013, 41, 1695–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, P.; Vale, N.; Moreira, R. Cyclization-activated prodrugs. Molecules 2007, 12, 2484–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Merten, O.W.; Kierulff, J.V.; Castignolles, N.; Perrin, P. Evaluation of the new serum-free medium (MDSS2) for the production of different biologicals: Use of various cell lines. Cytotechnology 1994, 14, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emeny, J.M.; Morgan, M.J. Regulation of the interferon system: Evidence that Vero cells have a genetic defect in interferon production. J. Gen. Virol. 1979, 43, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiesslich, S.; Kamen, A.A. Vero cell upstream bioprocess development for the production of viral vectors and vaccines. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 44, 107608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hayati, R.F.; Better, C.D.; Denis, D.; Komarudin, A.G.; Bowolaksono, A.; Yohan, B.; Sasmono, R.T. [6]-Gingerol Inhibits Chikungunya Virus Infection by Suppressing Viral Replication. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6623400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khongwichit, S.; Wikan, N.; Abere, B.; Thepparit, C.; Kuadkitkan, A.; Ubol, S.; Smith, D.R. Cell-type specific variation in the induction of ER stress and downstream events in chikungunya virus infection. Microb. Pathog. 2016, 101, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matusali, G.; Colavita, F.; Bordi, L.; Lalle, E.; Ippolito, G.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Castilletti, C. Tropism of the Chikungunya Virus. Viruses 2019, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ekchariyawat, P.; Hamel, R.; Bernard, E.; Wichit, S.; Surasombatpattana, P.; Talignani, L.; Thomas, F.; Choumet, V.; Yssel, H.; Desprès, P.; et al. Inflammasome signaling pathways exert antiviral effect against Chikungunya virus in human dermal fi-broblasts. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 32, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestle, F.O.; Di Meglio, P.; Qin, J.Z.; Nickoloff, B.J. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reis, E.V.S.; Damas, B.M.; Mendonça, D.C.; Abrahão, J.S.; Bonjardim, C.A. In-Depth Characterization of the Chikungunya Virus Replication Cycle. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0173221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Edwards, T.; Del Carmen Castillo Signor, L.; Williams, C.; Larcher, C.; Espinel, M.; Theaker, J.; Donis, E.; Cuevas, L.E.; Adams, E.R. Analytical and clinical performance of a Chikungunya qRT-PCR for Central and South America. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 89, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lani, R.; Hassandarvish, P.; Shu, M.H.; Phoon, W.H.; Chu, J.J.; Higgs, S.; Vanlandingham, D.; Abu Bakar, S.; Zandi, K. Antiviral activity of selected flavonoids against Chikungunya virus. Antivir. Res. 2016, 133, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.Z.; Larson, G.; Walker, H.; Shim, J.H.; Hong, Z. Phosphorylation of ribavirin and viramidine by adenosine kinase and cyto-solic 5′-nucleotidase II: Implications for ribavirin metabolism in erythrocytes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2164–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rojas-Luna, L.; Posadas-Modragón, A.; Avila-Trejo, A.M.; Alcántara-Farfán, V.; Rodríguez-Páez, L.I.; Santiago-Cruz, J.A.; Pas-tor-Alonso, M.O.; Aguilar-Faisal, J.L. Inhibition of chikungunya virus replication by N-ω-Chloroacetyl-L-Ornithine in C6/36, Vero cells and human fibroblast BJ. Antivir. Ther. 2023, 28, 13596535231155263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Dai, J.; An, Z.; Hu, R.; Duan, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Chu, Z.; Liu, H.; et al. 1-Formyl-β-carboline Derivatives Block Newcastle Disease Virus Proliferation through Suppressing Viral Adsorption and Entry Processes. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu, Y.H.; Wang, M.; Lin, J.Q.; Wang, M.Y.; Zhou, L.Y.; He, S.H.; Yi, Y.T.; Wei, X.; Huang, Q.J.; Su, Z.H.; et al. Fufang Luohanguo Qingfei granules reduces influenza virus susceptibility via MAVS-dependent type I interferon antiviral signaling. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 324, 117780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- More, G.K.; Vervoort, J.; Steenkamp, P.A.; Prinsloo, G. Metabolomic profile of medicinal plants with anti-RVFV activity. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Malakar, S.; Sreelatha, L.; Dechtawewat, T.; Noisakran, S.; Yenchitsomanus, P.T.; Chu, J.J.H.; Limjindaporn, T. Drug repurposing of quinine as antiviral against dengue virus infection. Virus Res. 2018, 255, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, X.; Lai, F.; Zhang, X.; Wu, H.; Min, T. Betaine Inhibits Hepatitis B Virus with an Advantage of Decreasing Re-sistance to Lamivudine and Interferon α. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 4068–4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mufti, I.U.; Ain, Q.U.; Malik, A.; Shahid, I.; Alzahrani, A.R.; Ijaz, B.; Rehman, S. Exploring antiviral activity of Betanin and Glycine Betaine against dengue virus type-2 in transfected Hela cells. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 195, 106894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Concentration (µg/mL) | Cell Viability (%) ± SEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SP-H | SP-D | SP-M | |

| 50 | 96.4 ± 5.37 | 98.6 ± 7.84 | 106.7 ± 11.4 |

| 100 | 99.8 ± 6.72 | 97.3 ± 8.34 | 96.49 ± 8.9 |

| Concentration (µg/mL) | % PFU’s ± SEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SP-H | SP-D | SP-M | |

| 50 | 99.78 ± 7.61 | 89.91 ± 7.91 | 0 |

| 100 | 104.2 ± 5.77 | 55.04 ± 14.47 * | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santiago-Cruz, J.A.; Posadas-Mondragón, A.; Aguilar-Faisal, J.L.; Ortiz-García, C.I.; Montalvan-Sorrosa, D.; Herrera-González, N.E.; Pérez-Juárez, A. In Vitro Evaluation of the Antiviral Effect of Spirulina maxima (Arthrospira) Alga Against Chikungunya Virus. Viruses 2025, 17, 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121583

Santiago-Cruz JA, Posadas-Mondragón A, Aguilar-Faisal JL, Ortiz-García CI, Montalvan-Sorrosa D, Herrera-González NE, Pérez-Juárez A. In Vitro Evaluation of the Antiviral Effect of Spirulina maxima (Arthrospira) Alga Against Chikungunya Virus. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121583

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantiago-Cruz, José Angel, Araceli Posadas-Mondragón, José Leopoldo Aguilar-Faisal, Cesar Ismael Ortiz-García, Danai Montalvan-Sorrosa, Norma Estela Herrera-González, and Angélica Pérez-Juárez. 2025. "In Vitro Evaluation of the Antiviral Effect of Spirulina maxima (Arthrospira) Alga Against Chikungunya Virus" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121583

APA StyleSantiago-Cruz, J. A., Posadas-Mondragón, A., Aguilar-Faisal, J. L., Ortiz-García, C. I., Montalvan-Sorrosa, D., Herrera-González, N. E., & Pérez-Juárez, A. (2025). In Vitro Evaluation of the Antiviral Effect of Spirulina maxima (Arthrospira) Alga Against Chikungunya Virus. Viruses, 17(12), 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121583