Defining and Predicting HIV Immunological Non-Response: A Multi-Definition Analysis from an Indonesian Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Definitions and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Immunological Response and Non-Response Characteristics Among Indonesian HIV Patients

3.2. Clinical and Demographic Predictors of Immunological Non-Response

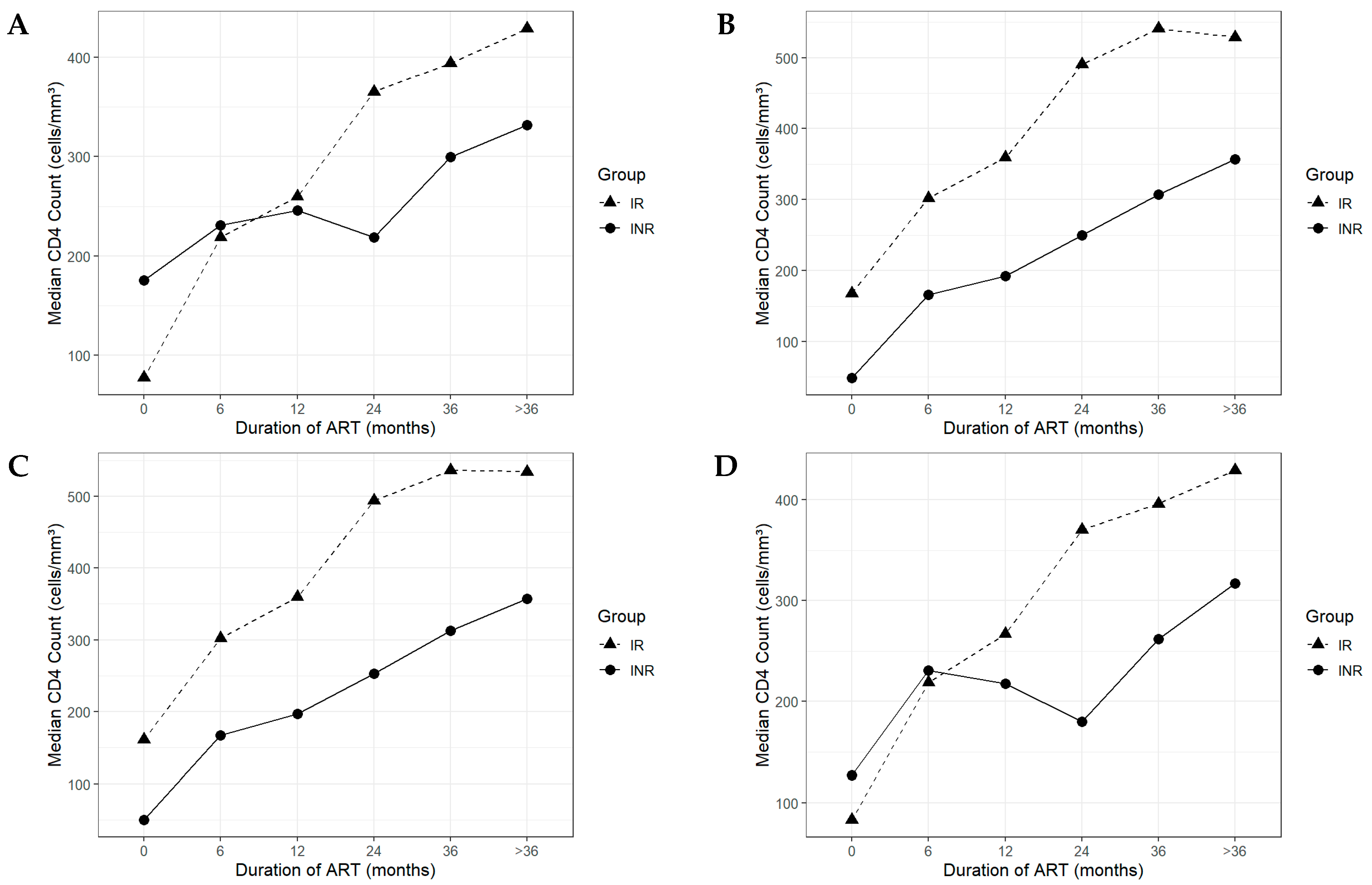

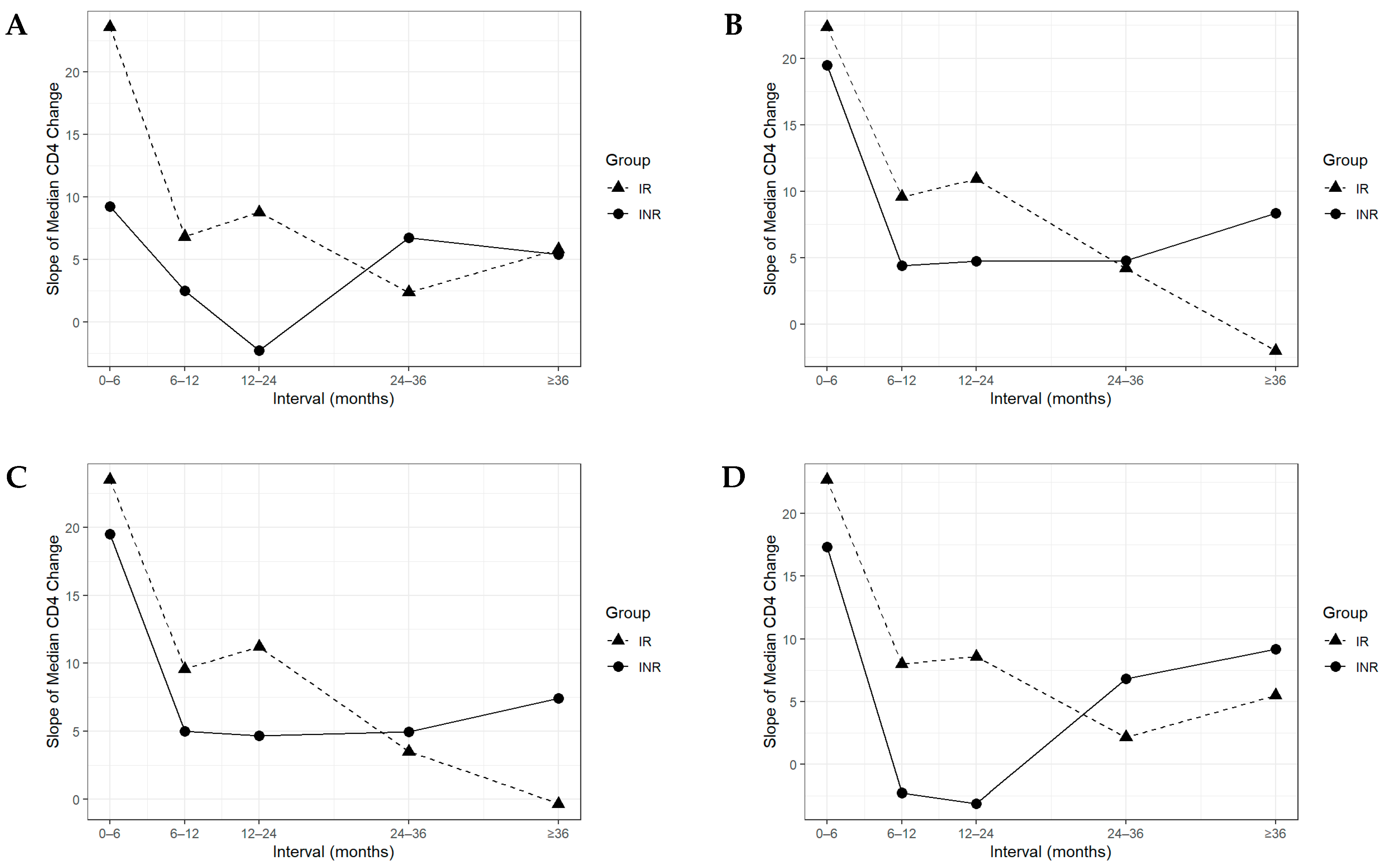

3.3. Longitudinal CD4+ Recovery Patterns in Immunological Responders and Non-Responders

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIDS | Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome |

| ART | Antiretroviral therapy |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CD4+ | Cluster of differentiation 4 |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| INR | Immunological nonresponder |

| IR | Immunological responder |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LMICs | Low- and middle-income countries |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PLHIV | People living with HIV |

| p-value | Probability value |

| Ref. | Reference |

| RS | Rumah Sakit (hospital) |

| SD | Standard deviations |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| TDF | Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Noiman, A.; Esber, A.; Wang, X.; Bahemana, E.; Adamu, Y.; Iroezindu, M.; Kiweewa, F.; Maswai, J.; Owuoth, J.; Maganga, L.; et al. Clinical Factors and Outcomes Associated with Immune Non-Response among Virally Suppressed Adults with HIV from Africa and the United States. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Feng, A.; Luo, D.; Yuan, T.; Lin, Y.F.; Ling, X.; Zhong, H.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Zou, H. Factors Associated with Immunological Non-Response after ART Initiation: A Retrospective Observational Cohort Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Su, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, T. Incomplete Immune Reconstitution in HIV/AIDS Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy: Challenges of Immunological Non-responders. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 107, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, L.; Li, P.; Yu, A.; Liu, D.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zou, M.; Ma, P. Prevalence of and Prognosis for Poor Immunological Recovery by Virally Suppressed and Aged HIV-Infected Patients. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1259871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandera, A.; Masetti, M.; Fabbiani, M.; Biasin, M.; Muscatello, A.; Squillace, N.; Clerici, M.; Gori, A.; Trabattoni, D. The NLRP3 Inflammasome Is Upregulated in HIV-Infected Antiretroviral Therapy-Treated Individuals with Defective Immune Recovery. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroeze, S.; Rossouw, T.; Steel, H.; Wit, F.; Kityo, C.; Siwale, M.; Akanmu, A.; Mandaliya, K.; Jager, M.; Ondoa, P.; et al. Plasma Inflammatory Biomarkers Predict CD4+ T-Cell Recovery and Viral Rebound in HIV-1 Infected Africans on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 224, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahemana, E.; Esber, A.; Dear, N.; Ganesan, K.; Parikh, A.; Reed, D.; Maganga, L.; Khamadi, S.; Mizinduko, M.; Lwilla, A.; et al. Impact of Age on CD4 Recovery and Viral Suppression over Time among Adults Living with HIV Who Initiated Antiretroviral Therapy in the African Cohort Study. AIDS Res. Ther. 2020, 17, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, A.; Gelaw, B.; Mekonnen, G.; Yitayaw, G. The Effect of Incident Tuberculosis on Immunological Response of HIV Patients on Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapy at the University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: A Retrospective Follow-up Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayarsaikhan, S.; Jagdagsuren, D.; Gunchin, B.; Sandag, T. Survival, CD4 T Lymphocyte Count Recovery and Immune Reconstitution Pattern during the First-Line Combination Antiretroviral Therapy in Patients with HIV-1 Infection in Mongolia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiseha, T.; Ebrahim, H.; Ebrahim, E.; Gebreweld, A. CD4+ Cell Count Recovery after Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in HIV-Infected Ethiopian Adults. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanobberghen, F.; Kilama, B.; Wringe, A.; Ramadhani, A.S.; Zaba, B.; Mmbando, D.; Todd, J. Immunological Failure of First-Line and Switch to Second-Line Antiretroviral Therapy among HIV-Infected Persons in Tanzania: Analysis of Routinely Collected National Data. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2015, 20, 880–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limmade, Y.; Fransisca, L.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, R.; Bangs, M.J.; Rothe, C. HIV Treatment Outcomes Following Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation and Monitoring: A Workplace Program in Papua, Indonesia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; França, E.; Costa, I.; Jorge, E.; Mendonça-Mattos, P.; Freire, A.; Ramos, F.; Monteiro, T.; Macedo, O.; Medeiros, R.; et al. HLA-B*13, B*35 and B*39 Alleles Are Closely Associated with the Lack of Response to ART in HIV Infection: A Cohort Study in a Population of Northern Brazil. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 829126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho-Silva, W.H.V.; Andrade-Santos, J.L.; Guedes, M.C.d.S.; Crovella, S.; Guimarães, R.L. CCR5 Genotype and Pre-Treatment CD4+ T-Cell Count Influence Immunological Recovery of HIV-Positive Patients during Antiretroviral Therapy. Gene 2020, 741, 144568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Feng, Y.; Lan, G.; Liang, S.; Liu, M.; Rashid, A.; Xing, H.; Shen, Z.; et al. Immune Reconstruction Effectiveness of Combination Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV-1 CRF01_AE Cluster 1 and 2 Infected Individuals. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairunisa, S.Q.; Megasari, N.L.A.; Ueda, S.; Budiman, W.; Kotaki, T.; Nasronudin; Kameoka, M. 2018–2019 Update on the Molecular Epidemiology of HIV-1 in Indonesia. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2020, 36, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairunisa, S.Q.; Indriati, D.W.; Megasari, N.L.A.; Ueda, S.; Kotaki, T.; Fahmi, M.; Ito, M.; Rachman, B.E.; Hidayati, A.N.; Nasronudin; et al. Spatial–Temporal Transmission Dynamics of HIV-1 CRF01_AE in Indonesia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembiring, J.; Indrati, A.; Amalia, W. Characteristics of Immunological Non-Responders in People Living with HIV at Abepura Hospital Papua. Indones. J. Clin. Pathol. Med. Lab. 2024, 30, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rb-Silva, R.; Goios, A.; Kelly, C.; Teixeira, P.; João, C.; Horta, A.; Correia-Neves, M. Definition of Immunological Nonresponse to Antiretroviral Therapy: A Systematic Review. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2019, 82, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, M.C.S.; Lopes-Araujo, H.F.; dos Santos, K.F.; Simões, E.; Carvalho-Silva, W.H.V.; Guimarães, R.L. How to Properly Define Immunological Nonresponse to Antiretroviral Therapy in People Living with HIV? An Integrative Review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1535565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; He, Q.; Huang, J.; Tang, K.; Fang, N.; Xie, H.; Ma, J.; Zhu, Q.; Lan, G.; Liang, S. Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Immunological Non-Responders in HIV-1-Infected Patients Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy: A Cross-Sectional Study in Guangxi. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negash, H.; Legese, H.; Tefera, M.; Mardu, F.; Tesfay, K.; Gebresilasie, S.; Fseha, B.; Kahsay, T.; Gebrewahd, A.; Berhe, B. The Effect of Tuberculosis on Immune Reconstitution among HIV Patients on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy in Adigrat General Hospital, Eastern Tigrai, Ethiopia; 2019: A Retrospective Follow up Study. BMC Immunol. 2019, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouamou, V.; Gundidza, P.; Ndhlovu, C.E.; Makadzange, A.T. Factors Associated with CD4+ Cell Count Recovery among Males and Females with Advanced HIV Disease. AIDS 2023, 37, 2311–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazis, N.; Paparizos, V.; Papastamopoulos, V.; Metallidis, S.; Antoniadou, A.; Adamis, G.; Psichgiou, M.; Chini, M.; Sambatakou, H.; Chrysos, G.; et al. Low Pre-ART CD4 Count Is Associated with Increased Risk of Clinical Progression or Death Even after Reaching 500 CD4 Cells/ΜL on ART. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lembas, A.; Załęski, A.; Mikuła, T.; Dyda, T.; Stańczak, W.; Wiercińska-Drapało, A. Evaluation of Clinical Biomarkers Related to CD4 Recovery in HIV-Infected Patients—5-Year Observation. Viruses 2022, 14, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hailu, G.G.; Wasihun, A.G. Immunological and Virological Discordance among People Living with HIV on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, A.A.; Woldearegay, T.W.; Berhe, A.A.; Futwi, N.; Gebru, G.G.; Godefay, H. Immunological Recovery, Failure and Factors Associated with CD-4 T-Cells Progression over Time, among Adolescents and Adults Living with HIV on Antiretroviral Therapy in Northern Ethiopia: A Retrospective Cross Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e226293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resop, R.S.; Salvatore, B.; Kim, S.J.; Gordon, B.R.; Blom, B.; Vatakis, D.N.; Uittenbogaart, C.H. HIV-1 Infection Results in Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor 1 Dysregulation in the Human Thymus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, T. HIV Impacts CD34+ Progenitors Involved in T-Cell Differentiation During Coculture with Mouse Stromal OP9-DL1 Cells. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Schank, M.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Nguyen, L.N.; Dang, X.; Cao, D.; Khanal, S.; Nguyen, L.N.T.; Thakuri, B.K.C.; et al. Mitochondrial Functions Are Compromised in CD4 T Cells From ART-Controlled PLHIV. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 658420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Andreu-Sánchez, S.; Vadaq, N.; Wang, D.; Matzaraki, V.; van der Heijden, W.A.; Gacesa, R.; Weersma, R.K.; Zhernakova, A.; Vandekerckhove, L.; et al. Gut Dysbiosis Associates with Cytokine Production Capacity in Viral-Suppressed People Living with HIV. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1202035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aya, I.; Michiko, K.; Taketoshi, M.; Kofi, P.P.; Diki, P.; Nozomi, Y.; Ayako, S.; Tadashi, K.; Kazuhiko, I.; Eisuke, A.; et al. Unique Gut Microbiome in HIV Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Suggests Association with Chronic Inflammation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0070821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidayat, J.; Chen, M.-Y.; Maulina, R.; Nurbaya, S. Factors Associated with HIV-Related Stigma Among Indonesian Healthcare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. J. Nurs. Res. 2023, 31, e295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauk, N.K.; Ward, P.R.; Hawke, K.; Mwanri, L. HIV Stigma and Discrimination: Perspectives and Personal Experiences of Healthcare Providers in Yogyakarta and Belu, Indonesia. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 625787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; Arifin, H.; Fitri, S.U.R.; Herliani, Y.K.; Harun, H.; Setiawan, A.; Lee, B.-O. The Optimization of HIV Testing in Eastern Indonesia: Findings from the 2017 Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey. Healthcare 2022, 10, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhabokritsky, A.; Szadkowski, L.; Burchell, A.N.; Cooper, C.; Hogg, R.S.; Hull, M.; Kelly, D.V.; Klein, M.; Loutfy, M.; McClean, A.; et al. Immunological and Virological Response to Initial Antiretroviral Therapy among Older People Living with HIV in the Canadian Observational Cohort (CANOC). HIV Med. 2021, 22, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, M.C.S.; Carvalho-Silva, W.H.V.; Andrade-Santos, J.L.; Brelaz-de-Castro, M.C.A.; Souto, F.O.; Montenegro, L.M.L.; Guimarães, R.L. HIV-Induced Thymic Insufficiency and Aging-Related Immunosenescence on Immune Reconstitution in ART-Treated Patients. Vaccines 2024, 12, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Wang, W.; Su, D.M. Contributions of Age-Related Thymic Involution to Immunosenescence and Inflammaging. Immun. Ageing 2020, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.-Y.; Wang, X.-W.; Li, S.; Li, N.; Li, W.; Hu, Y.; Guo, N.; Zheng, Y.-T.; Zheng, H.-Y.; Su, B. Immunosenescence and Its Related Comorbidities in Older People Living with HIV. Infect. Dis. Immun. 2025, 5, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Guedes, M.C.; Carvalho-Silva, W.H.V.; Andrade-Santos, J.L.; Brelaz-de-Castro, M.C.A.; Souto, F.O.; Guimarães, R.L. Thymic Exhaustion and Increased Immune Activation Are the Main Mechanisms Involved in Impaired Immunological Recovery of HIV-Positive Patients under ART. Viruses 2023, 15, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Xu, L.; Qian, Z.; Sun, X. Infection-Associated Thymic Atrophy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 652538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phu, T.; Nhung, H. The Relationship Between Baseline CD4 T Cells’ Level And Recovery Rate After Initiation Of Art In HIV/AIDS Infected At Hospital For Tropical Diseases, Vietnam. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2020, 13, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massanella, M.; Bender Ignacio, R.A.; Lama, J.R.; Pagliuzza, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Alfaro, R.; Rios, J.; Ganoza, C.; Pinto-Santini, D.; Gilada, T.; et al. Long-Term Effects of Early Antiretroviral Initiation on HIV Reservoir Markers: A Longitudinal Analysis of the MERLIN Clinical Study. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e198–e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wang, Q.; Ghneim, K.; Wang, L.; Rampanelli, E.; Holley-Guthrie, E.; Cheng, L.; Garrido, C.; Margolis, D.M.; Eller, L.A.; et al. Multi-Omics Analyses Reveal That HIV-1 Alters CD4+ T Cell Immunometabolism to Fuel Virus Replication. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischhaber, N.; Schmiedeberg, M.; Kübel, S.; Harrer, E.G.; Harrer, T.; Nganou-Makamdop, K. Ex Vivo Blockade of the PD-1 Pathway Improves Recall IFNγ Responses of HIV-Infected Persons on Antiretroviral Therapy. Vaccines 2023, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchus-Souffan, C.; Fitch, M.; Symons, J.; Abdel-Mohsen, M.; Reeves, D.B.; Hoh, R.; Stone, M.; Hiatt, J.; Kim, P.; Chopra, A.; et al. Relationship between CD4 T Cell Turnover, Cellular Differentiation and HIV Persistence during ART. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasna, Z.R.A.; Sunggoro, A.J.; Marwanta, S.; Harioputro, D.R.; Misganie, Y.G.; Khairunisa, S.Q. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as Predictors of CD4 Count among People Living with HIV. Indones. J. Trop. Infect. Dis. 2024, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saefudin, S.; Satuti, N. The Role of Host Genetics Regulating Proteins in HIV-1 Susceptibility: Epidemiological and Demographic Insights on HIV-1 in Indonesia (2022). Indones. J. Trop. Infect. Dis. 2024, 12, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beckhoven, D.; Florence, E.; De Wit, S.; Wyndham-Thomas, C.; Sasse, A.; Van Oyen, H.; Macq, J.; the Belgian Research on AIDS, H.I.V.C. (BREACH). Incidence Rate, Predictors and Outcomes of Interruption of HIV Care: Nationwide Results from the Belgian HIV Cohort. HIV Med. 2020, 21, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, B.; Byemerwa, J.; Krebs, T.; Lim, F.; Chang, C.-Y.; McDonnell, D.P. Estrogen Receptor Signaling in the Immune System. Endocr. Rev. 2023, 44, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, B.A.; Hanna, D.B.; Xue, X.; Weber, K.; Appleton, A.A.; Kassaye, S.G.; Topper, E.; Tracy, R.P.; Guillemette, C.; Caron, P.; et al. Menopause and Estrogen Associations with Gut Barrier, Microbial Translocation, and Immune Activation Biomarkers in Women with and without HIV. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2024, 96, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abelman, R.; Tien, P.C. The Reproductive Transition: Effects on Viral Replication, Immune Activation, and Metabolism in Women with HIV Infection. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2022, 19, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizzell, S.; Nazli, A.; Reid, G.; Kaushic, C. Protective Effect of Probiotic Bacteria and Estrogen in Preventing HIV-1-Mediated Impairment of Epithelial Barrier Integrity in Female Genital Tract. Cells 2019, 8, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Ba’are, G.R.; Shamrock, O.W.; Zigah, E.Y.; Ogunbajo, A.; Dakpui, H.D.; Agbemedu, G.R.K.; Boyd, D.T.; Ezechi, O.C.; Nelson, L.E.; Torpey, K. Qualitative Description of Interpersonal HIV Stigma and Motivations for HIV Testing among Gays, Bisexuals, and Men Who Have Sex with Men in Ghana’s Slums—BSGH-005. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0289905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boatman, J.A.; Baker, J.V.; Emery, S.; Furrer, H.; Mushatt, D.M.; Sedláček, D.; Lundgren, J.D.; Neaton, J.D.; the INSIGHT START Study Group. Risk Factors for Low CD4+ Count Recovery Despite Viral Suppression Among Participants Initiating Antiretroviral Treatment with CD4+ Counts > 500 Cells/Mm3: Findings From the Strategic Timing of AntiRetroviral Therapy (START) Trial. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2019, 81, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalichman, S.; Katner, H.; El-Krab, R.; Hill, M.; Ewing, W.; Kalichman, M. HIV Stigma Experiences and Alcohol Use Among Patients Receiving Medical Care in the Rural South. J. Rural. Ment. Health 2021, 45, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camlin, C.S.; Charlebois, E.D.; Getahun, M.; Akatukwasa, C.; Atwine, F.; Itiakorit, H.; Bakanoma, R.; Maeri, I.; Owino, L.; Onyango, A.; et al. Pathways for Reduction of HIV-Related Stigma: A Model Derived from Longitudinal Qualitative Research in Kenya and Uganda. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020, 23, e25647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akatukwasa, C.; Getahun, M.; El Ayadi, A.M.; Namanya, J.; Maeri, I.; Itiakorit, H.; Owino, L.; Sanyu, N.; Kabami, J.; Ssemmondo, E.; et al. Dimensions of HIV-Related Stigma in Rural Communities in Kenya and Uganda at the Start of a Large HIV ‘Test and Treat’ Trial. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alckmin-Carvalho, F.; Pereira, H.; Oliveira, A.; Nichiata, L. Associations between Stigma, Depression, and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Brazilian Men Who Have Sex with Men Living with HIV. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 1489–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessie, Z.G.; Zewotir, T.; Mwambi, H.; North, D. Modelling Immune Deterioration, Immune Recovery and State-Specific Duration of HIV-Infected Women with Viral Load Adjustment: Using Parametric Multistate Model. BMC Public. Health 2020, 20, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado-Sánchez, I.; Rodríguez-Gallego, E.; Peraire, J.; Viladés, C.; Herrero, P.; Fanjul, F.; Gutiérrez, F.; Bernal, E.; Pelazas, R.; Leal, M.; et al. Glutaminolysis and Lipoproteins Are Key Factors in Late Immune Recovery in Successfully Treated HIV-Infected Patients. Clin. Sci. 2019, 133, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnovia, A. Comparing the Impact of Nutritional Supplementation Versus Standard Care on Immune Recovery in HIV-Positive Adults Initiating ART. Res. Invent. J. Sci. Exp. Sci. 2025, 5, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rismayanti, T.; Latipah, I.; Jawahir, I.; Kartini; Sari, I.N.; Komala, I. Biological Perspective Analysis on Education Level and Motivation in the Implementation of Premarital HIV Screening Tests: A Quantitative Study with a Cross-Sectional Design. J. Penelit. Pendidik. IPA 2024, 10, 3949–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canziani, A.; Sinnott, S. The Effect of Stress on the Progression and Development of HIV/AIDS. J. Stud. Res. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Xie, Z.; Huang, Y.; Luo, D. HIV-Related Stress Predicts Depression over Five Years among People Living with HIV. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1163604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Walias, F.; Ruiz-de-León, M.J.; Rosado-Sánchez, I.; Vázquez, E.; Leal, M.; Moreno, S.; Vidal, F.; Blanco, J.; Pacheco, Y.M.; Vallejo, A. New Signatures of Poor CD4 Cell Recovery after Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy in HIV-1-Infected Individuals: Involvement of MiR-192, IL-6, SCD14 and MiR-144. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikrishnan, A.K.; Ganesan, K.; Mehta, S.H.; Tomori, C.; Vasudevan, C.K.; Celentano, D.D.; Solomon, S.S. Prevalence and Correlates of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection among Spouses of Married Men Who Have Sex with Men in India. Int. J. STD AIDS 2022, 33, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Septarini, N.W.; Burns, S.; Maycock, B. THE CABE PROJECT: Developing a Model to Conceptualise the Sexual Attitudes, Behaviours, and Experiences of Men Who Have Sex with Men and Waria in Bali, Indonesia: Protocol for a Mixed-Methods Design within a Community-Engaged Research Study. Res. Methods Med. Health Sci. 2021, 3, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazuardi, E.; Newman, C.E.; Anintya, I.; Rowe, E.; Wirawan, D.N.; Wisaksana, R.; Subronto, Y.W.; Kusmayanti, N.A.; Iskandar, S.; Kaldor, J.; et al. Increasing HIV Treatment Access, Uptake and Use among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Urban Indonesia: Evidence from a Qualitative Study in Three Cities. Health Policy Plan. 2020, 35, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Zhao, Y.; Long, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y. The Effect of Perceived Social Support on the Mental Health of Homosexuals: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunman, S.; Wannapaschaiyong, P.; Saiyasalee, S.; Pornma, K. Health Literacy Among Individuals Living with HIV. Bangk. Med. J. 2022, 18, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | INR1 n = 50 (13%) | IR1 n = 332 (87%) | p-Value | INR2 n = 200 (52%) | IR2 n = 182 (48%) | p-Value | INR3 n = 207 (54%) | IR3 n = 175 (46%) | p-Value | INR4 n = 43 (11%) | IR4 n = 339 (89%) | p-Value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | 0.477 | 0.161 | 0.071 | 0.896 | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 32 | (64%) | 191 | (58%) | 124 | (62%) | 99 | (54%) | 130 | (63%) | 93 | (53%) | 26 | (60%) | 197 | (58%) | ||||

| Female | 18 | (36%) | 141 | (42%) | 76 | (38%) | 83 | (46%) | 77 | (37%) | 82 | (47%) | 17 | (40%) | 142 | (42%) | ||||

| Age, n (%) | 0.112 | 0.530 | 0.379 | 0.193 | ||||||||||||||||

| ≥50 years | 6 | (12%) | 17 | (5%) | 14 | (7%) | 9 | (5%) | 15 | (7%) | 8 | (5%) | 5 | (12%) | 18 | (5%) | ||||

| <50 years | 44 | (88%) | 315 | (95%) | 186 | (93%) | 173 | (95%) | 192 | (93%) | 167 | (95%) | 38 | (88%) | 321 | (95%) | ||||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 31 | (27, 41.5) | 34 | (29, 40) | 0.32 | 34 | (29, 40) | 33 | (28, 40) | 0.273 | 34 | (29, 40) | 33 | (28, 39.5) | 0.274 | 31 | (27, 41) | 34 | (29, 40) | 0.292 |

| Mode of HIV Transmission, n (%) | 0.479 | 0.048 | 0.062 | 0.268 | ||||||||||||||||

| Vaginal sexual transmission | 41 | (82%) | 269 | (81%) | 165 | (83%) | 145 | (80%) | 171 | (83%) | 139 | (79%) | 35 | (81%) | 275 | (81%) | ||||

| Anal sexual transmission | 3 | (6%) | 38 | (11%) | 16 | (8%) | 25 | (14%) | 17 | (8%) | 24 | (14%) | 2 | (5%) | 39 | (12%) | ||||

| Injection drug use | 1 | (2%) | 6 | (2%) | 2 | (1%) | 5 | (3%) | 2 | (1%) | 5 | (3%) | 1 | (2%) | 6 | (2%) | ||||

| Other routes | 5 | (10%) | 19 | (6%) | 17 | (9%) | 7 | (4%) | 17 | (8%) | 7 | (4%) | 5 | (12%) | 19 | (6%) | ||||

| Body Mass Index (BMI) Category, n (%) | 0.77 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.457 | ||||||||||||||||

| Underweight | 17 | (34%) | 106 | (32%) | 80 | (40%) | 43 | (24%) | 81 | (39%) | 42 | (24%) | 16 | (37%) | 107 | (32%) | ||||

| Non-underweight | 33 | (66%) | 226 | (68%) | 120 | (60%) | 139 | (76%) | 126 | (61%) | 133 | (76%) | 27 | (63%) | 232 | (68%) | ||||

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 20.2 | (17.9, 23.4) | 20.3 | (17.7, 23.5) | 0.905 | 19.8 | (17.6, 21.8) | 21.8 | (18.6, 24.8) | <0.001 | 19.8 | (17.6, 21.8) | 21.8 | (18.6, 24.8) | <0.001 | 20.1 | (17.8, 23.4) | 20.3 | (17.8, 23.4) | 0.935 |

| Tuberculosis (TB) Status, n (%) | 0.951 | 0.749 | 0.948 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||

| Active TB at ART initiation | 5 | (10%) | 38 | (11%) | 24 | (12%) | 19 | (10%) | 24 | (12%) | 19 | (11%) | 5 | (12%) | 38 | (11%) | ||||

| No active TB at ART initiation | 45 | (90%) | 294 | (89%) | 176 | (88%) | 163 | (90%) | 183 | (88%) | 156 | (89%) | 38 | (88%) | 301 | (89%) | ||||

| HIV Clinical Stage, n (%) | 0.067 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.873 | ||||||||||||||||

| Non-Advanced HIV Disease | 7 | (14%) | 22 | (7%) | 3 | (2%) | 26 | (14%) | 7 | (3%) | 22 | (13%) | 3 | (7%) | 26 | (8%) | ||||

| Advanced HIV Disease | 43 | (86%) | 310 | (93%) | 197 | (99%) | 156 | (86%) | 200 | (97%) | 153 | (87%) | 40 | (93%) | 313 | (92%) | ||||

| ART Regimen, n (%) | 0.383 | 0.031 | 0.05 | 0.216 | ||||||||||||||||

| TDF-based Regimen | 19 | (38%) | 148 | (45%) | 77 | (38.5%) | 90 | (49%) | 126 | (61%) | 89 | (51%) | 15 | (35%) | 152 | (45%) | ||||

| Non-TDF-based Regimen | 31 | (62%) | 184 | (55%) | 123 | (61.5%) | 92 | (51%) | 81 | (39%) | 86 | (49%) | 28 | (65%) | 187 | (55%) | ||||

| Educational Attainment, n (%) | 0.586 | 0.081 | 0.012 | 0.542 | ||||||||||||||||

| Less than a Bachelor’s degree | 40 | (80%) | 276 | (83%) | 159 | (80%) | 157 | (86%) | 162 | (78%) | 154 | (88%) | 37 | (86%) | 279 | (82%) | ||||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 10 | (20%) | 56 | (17%) | 41 | (21%) | 25 | (14%) | 45 | (22%) | 21 | (12%) | 6 | (14%) | 60 | (18%) | ||||

| Baseline CD4+ count, n (%) | 0.008 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.360 | ||||||||||||||||

| <200 cells/mm3 | 29 | (58%) | 254 | (77%) | 182 | (91%) | 101 | (55%) | 182 | (88%) | 101 | (58%) | 29 | (67%) | 254 | (75%) | ||||

| ≥200 cells/mm3 | 21 | (42%) | 78 | (23%) | 18 | (9%) | 81 | (45%) | 25 | (12%) | 74 | (42%) | 14 | (33%) | 85 | (25%) | ||||

| Baseline CD4+ count (cells/mm3), median (IQR) | 176 | (45.5, 258) | 77.5 | (24, 190) | 0.005 | 49 | (19, 121) | 168 | (53.3, 277) | <0.001 | 49 | (19, 129) | 168 | (50.5, 263) | <0.001 | 127 | (43, 226) | 83 | (26, 198) | 0.181 |

| Variable | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.388 | |||

| Female | Ref. | |||

| Male | 1.31 (0.7–2.43) | |||

| Mode of HIV Transmission | ||||

| Vaginal sexual transmission | Ref. | |||

| Anal sexual transmission | 0.5 (0.15–1.75) | 0.29 | ||

| Injection drug use | 1.09 (0.12–9.31) | 0.93 | ||

| Other routes | 1.72 (0.61–4.87) | 0.30 | ||

| BMI Category | 0.77 | |||

| Non-underweight | Ref. | |||

| Underweight | 1.09 (0.58–2.06) | |||

| HIV Clinical Stage | 0.07 | 0.64 | ||

| Non-Advanced HIV Disease | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Advanced HIV Disease | 0.43 (0.17–1.08) | 0.78 (0.28–2.2) | ||

| ART Regimen | 0.38 | |||

| TDF-based Regimen | Ref. | |||

| Non-TDF-based Regimen | 1.31 (0.71–2.41) | |||

| Baseline CD4+ count | 0.006 | 0.028 | ||

| >200 cells/mm3 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| <200 cells/mm3 | 0.42 (0.22–0.78) | 0.45 (0.22–0.92) | ||

| Educational Attainment | 0.58 | |||

| Less than a Bachelor’s Degree | Ref. | |||

| Bachelor’s Degree or higher | 1.23 (0.58–2.6) |

| Variable | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.13 | |||

| Female | Ref. | Ref. | 0.06 | |

| Male | 1.36 (0.909–2.06) | 1.62 (0.97–2.69) | ||

| Mode of HIV Transmission | ||||

| Vaginal sexual transmission | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Anal sexual transmission | 0.56 (0.28–1.09) | 0.09 | 0.42 (0.19–0.92) | 0.03 |

| Injection drug use | 0.35 (0.06–1.84) | 0.21 | 0.19 (0.03–1.11) | 0.06 |

| Other routes | 2.13 (0.86–5.29) | 0.102 | 1.07 (0.38–3) | 0.89 |

| BMI Category | 0.001 | 0.083 | ||

| Non-underweight | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Underweight | 2.15 (1.38–3.36) | 1.54 (0.94–2.53) | ||

| HIV Clinical Stage | 0.001 | 0.13 | ||

| Non-Advanced HIV Disease | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Advanced HIV Disease | 10.94 (3.25–36.82) | 2.8 (0.72–10.79) | ||

| ART Regimen | 0.032 | 0.13 | ||

| TDF-based Regimen | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Non-TDF-based Regimen | 1.56 (1.04–2.35) | 1.44 (0.89–2.34) | ||

| Baseline CD4+ count | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| >200 cells/mm3 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| <200 cells/mm3 | 8.1 (4.6–14.27) | 5.6 (2.95–10.62) | ||

| Educational Attainment | 0.082 | 0.021 | ||

| Less than a Bachelor’s Degree | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Bachelor’s Degree or higher | 1.62 (0.94–2.79) | 2.08 (1.11–3.9) |

| Variable | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.057 | 0.02 | ||

| Female | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Male | 1.48 (0.98–2.24) | 1.78 (1.08–2.94) | ||

| Mode of HIV Transmission | ||||

| Vaginal sexual transmission | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Anal sexual transmission | 0.57 (0.29–1.11) | 0.1 | 0.41 (0.19–0.89) | 0.02 |

| Injection drug use | 0.32 (0.06–1.7) | 0.18 | 0.18 (0.03–1.05) | 0.05 |

| Other routes | 1.97 (0.79–4.9) | 0.14 | 0.96 (0.35–2.69) | 0.93 |

| BMI Category | 0.002 | 0.07 | ||

| Non-underweight | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Underweight | 2.03 (1.3–3.18) | 1.56 (0.95–2.54) | ||

| HIV Clinical Stage | 0.002 | 0.65 | ||

| Non-Advanced HIV Disease | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Advanced HIV Disease | 4.1 (1.71–9.86) | 1.26 (0.44–3.59) | ||

| ART Regimen | 0.05 | 0.09 | ||

| TDF-based Regimen | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Non-TDF-based Regimen | 1.5 (1.00–2.26) | 1.49 (0.92–2.39) | ||

| Baseline CD4+ count | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| >200 cells/mm3 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| <200 cells/mm3 | 5.33 (3.18–8.92) | 4.46 (2.39–8.29) | ||

| Educational Attainment | 0.003 | |||

| Less than a Bachelor’s Degree | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Bachelor’s Degree or higher | 2.04 (1.16–3.58) | 0.013 | 2.62 (1.4–4.91) |

| Variable | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.76 | |||

| Female | Ref. | |||

| Male | 1.1 (0.57–2.1) | |||

| Mode of HIV Transmission | ||||

| Vaginal sexual transmission | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Anal sexual transmission | 0.4 (0.09–1.74) | 0.22 | 0.41 (0.09–1.79) | 0.23 |

| Injection drug use | 1.31 (0.15–11.19) | 0.8 | 1.15 (0.13–10.01) | 0.89 |

| Other routes | 2.06 (0.72–5.88) | 0.17 | 1.83 (0.62–5.39) | 0.26 |

| BMI Category | 0.45 | |||

| Non-underweight | Ref. | |||

| Underweight | 1.28 (0.66–2.48) | |||

| HIV Clinical Stage | 0.27 | |||

| Non-Advanced HIV Disease | Ref. | |||

| Advanced HIV Disease | 0.68 (0.34–1.35) | |||

| ART Regimen | 0.218 | 0.39 | ||

| TDF-based Regimen | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Non-TDF-based Regimen | 1.51 (0.78–2.94) | 1.35 (0.67–2.69) | ||

| Baseline CD4+ count | 0.293 | |||

| >200 cells/mm3 | Ref. | |||

| <200 cells/mm3 | 0.69 (0.35–1.37) | |||

| Educational Attainment | 0.54 | |||

| Less than a Bachelor’s Degree | Ref. | |||

| Bachelor’s Degree or higher | 0.75 (0.3–1.86) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rachman, B.E.; Supranoto, Y.T.N.; Iskandar, S.I.; Asmarawati, T.P.; Khairunisa, S.Q.; Arfijanto, M.V.; Hadi, U.; Miftahussurur, M.; Nasronudin, N.; Kameoka, M.; et al. Defining and Predicting HIV Immunological Non-Response: A Multi-Definition Analysis from an Indonesian Cohort. Viruses 2025, 17, 1581. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121581

Rachman BE, Supranoto YTN, Iskandar SI, Asmarawati TP, Khairunisa SQ, Arfijanto MV, Hadi U, Miftahussurur M, Nasronudin N, Kameoka M, et al. Defining and Predicting HIV Immunological Non-Response: A Multi-Definition Analysis from an Indonesian Cohort. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1581. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121581

Chicago/Turabian StyleRachman, Brian Eka, Yehuda Tri Nugroho Supranoto, Soraya Isfandiary Iskandar, Tri Pudy Asmarawati, Siti Qamariyah Khairunisa, Muhammad Vitanata Arfijanto, Usman Hadi, Muhammad Miftahussurur, Nasronudin Nasronudin, Masanori Kameoka, and et al. 2025. "Defining and Predicting HIV Immunological Non-Response: A Multi-Definition Analysis from an Indonesian Cohort" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1581. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121581

APA StyleRachman, B. E., Supranoto, Y. T. N., Iskandar, S. I., Asmarawati, T. P., Khairunisa, S. Q., Arfijanto, M. V., Hadi, U., Miftahussurur, M., Nasronudin, N., Kameoka, M., Rahayu, R. P., & Hidayati, A. N. (2025). Defining and Predicting HIV Immunological Non-Response: A Multi-Definition Analysis from an Indonesian Cohort. Viruses, 17(12), 1581. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121581