Viral Coinfections Potentially Associated with Feline Chronic Gingivostomatitis in Cats with Feline Infectious Peritonitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Signalment, History, and Assessment of Clinical Signs, Including FCGS

2.3. Sample Collection and Processing

2.4. Hematology, Serum Proteins, and Acute Phase Proteins

2.5. Total Nucleic Acid (TNA) Extraction from Blood, Effusions, and Oropharyngeal Cytobrush Samples

2.6. Molecular Detection of Feline Viruses (Viral RNA/DNA or Proviral DNA)

2.7. Detection of FeLV p27 Antigen

2.8. Detection of FIV Antibodies

2.9. Statistics

2.10. Post-Mortem Examinations

3. Results

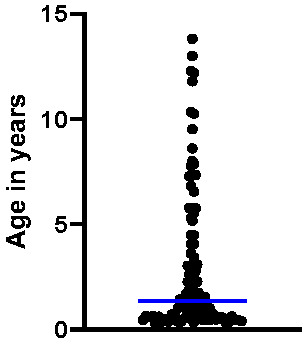

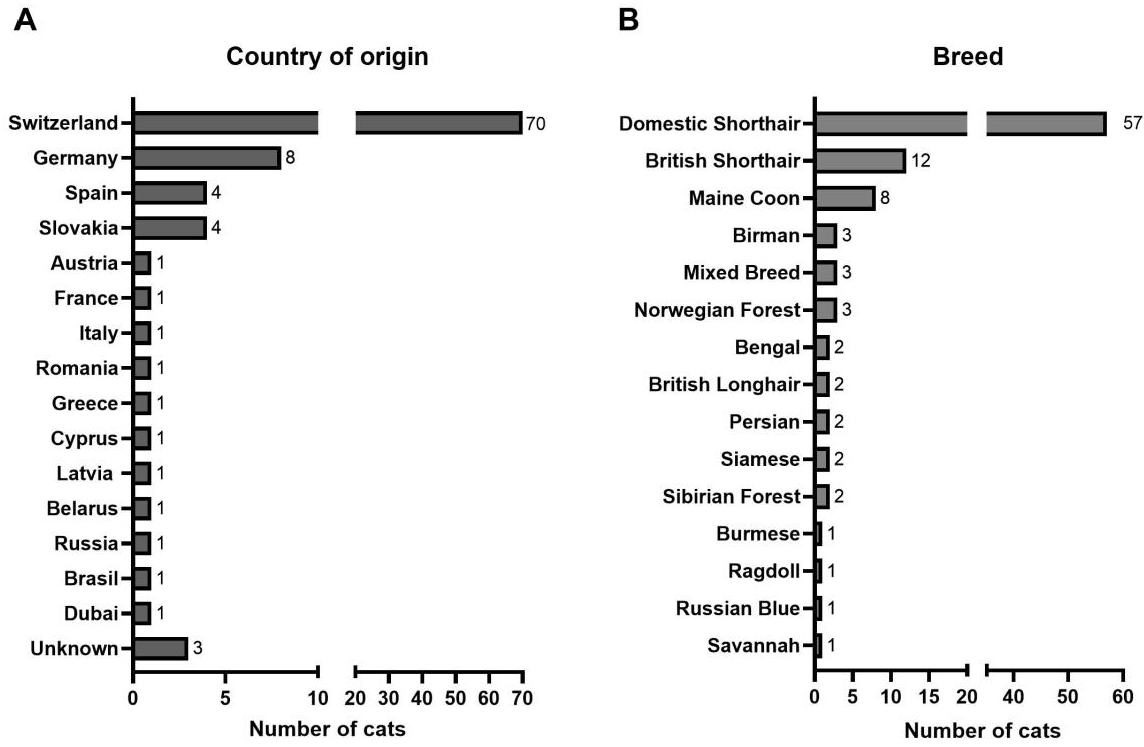

3.1. Characterization of the Study Population

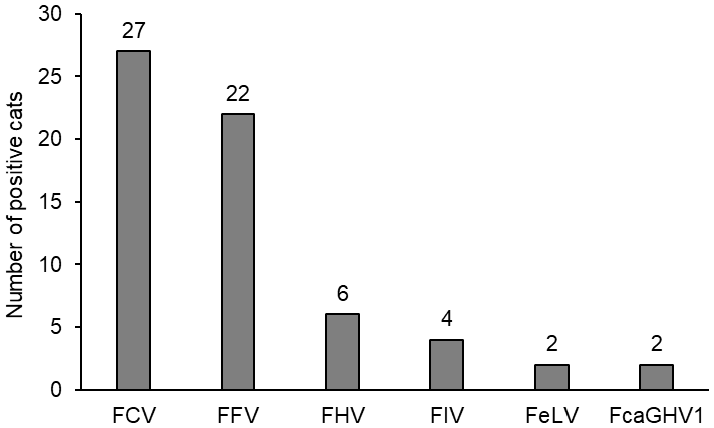

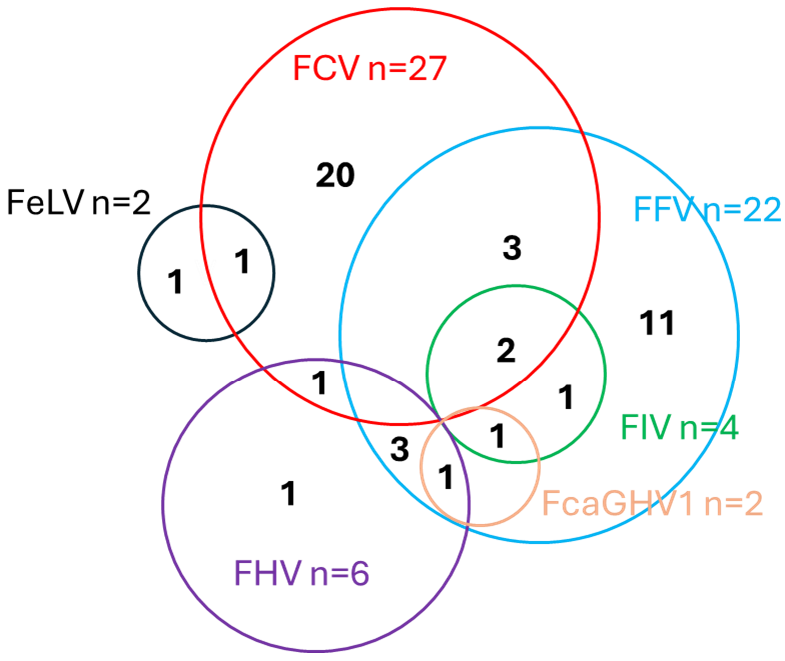

3.2. Prevalence of Viral Coinfections

3.3. Oropharyngeal Shedding of FCoV

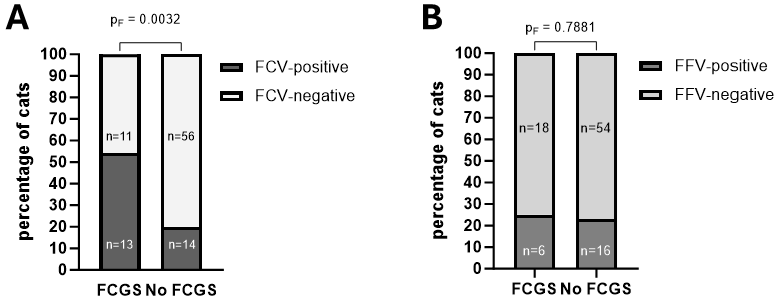

3.4. Influence of Coinfections on Prevalence and Severity of FCGS

3.5. Disease Severity and Outcome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Cat ID | Age (Years) | FCV/FHV Vaccination Up-to-Date 1 | Days Since Last Vaccination | FCV RT-qPCR | FHV qPCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #001 | 1.8 | Yes | 167 | Unavailable 2 | Unavailable 2 |

| #002 | 1.7 | Unknown | Unknown | Unavailable 2 | Unavailable 2 |

| #003 | 3.4 | No | 1049 | Unavailable 2 | Unavailable 2 |

| #004 | 0.8 | No | 66 | Positive | Negative |

| #006 | 5.2 | No | 295 | Positive | Negative |

| #007 | 1.3 | No | 406 | Positive | Negative |

| #008 | 0.8 | Yes | 23 | Positive | Negative |

| #009 | 1.1 | Yes | 246 | Negative | Negative |

| #010 | 4.1 | Yes | 111 | Negative | Negative |

| #011 | 0.6 | Yes | 434 | Negative | Negative |

| #012 | 0.7 | No | - | Negative | Negative |

| #013 | 0.9 | Yes | 110 | Negative | Negative |

| #015 | 1.1 | Yes | 129 | Negative | Positive |

| #017 | 10.3 | No | 1495 | Negative | Negative |

| #018 | 1.8 | Unknown | Unknown | Negative | Negative |

| #022 | 0.3 | Yes | 18 | Negative | Negative |

| #023 | 7.8 | Yes | 155 | Negative | Negative |

| #024 | 1.3 | Yes | 20 | Negative | Negative |

| #025 | 1.4 | No | 123 | Positive | Negative |

| #027 | 1.1 | Yes | 290 | Negative | Negative |

| #028 | 0.7 | Yes | 106 | Positive | Negative |

| #029 | 1.2 | Yes | 30 | Negative | Negative |

| #031 | 5.8 | Yes | 344 | Negative | Negative |

| #033 | 0.5 | Yes | 58 | Positive | Negative |

| #034 | 7.3 | No | 218 | Negative | Positive |

| #035 | 7.3 | Ja | 834 | Positive | Negative |

| #036 | 2.6 | Yes | 343 | Negative | Negative |

| #037 | 0.6 | Yes | 102 | Positive | Positive |

| #038 | 7.3 | Yes | 505 | Negative | Negative |

| #039 | 12.3 | No | 3271 | Negative | Negative |

| #040 | 0.4 | Yes | 48 | Negative | Negative |

| #041 | 4.5 | Unknown | Unknown | Negative | Negative |

| #042 | 0.4 | Yes | 22 | Positive | Negative |

| #043 | 0.5 | Yes | 63 | Negative | Negative |

| #044 | 0.4 | Yes | 210 | Negative | Negative |

| #045 | 0.5 | Yes | 70 | Positive | Negative |

| #046 | 3.1 | Yes | 285 | Negative | Negative |

| #047 | 3.0 | Yes | 269 | Negative | Negative |

| #048 | 13.0 | No | 3018 | Negative | Negative |

| #049 | 8.0 | No | Unknown | Positive | Negative |

| #050 | 1.2 | Yes | 318 | Negative | Negative |

| #051 | 4.1 | Yes | 118 | Negative | Positive |

| #052 | 0.4 | Yes | 46 | Negative | Negative |

| #053 | 0.4 | Yes | 68 | Positive | Negative |

| #054 | 1.3 | Yes | 257 | Positive | Negative |

| #055 | 2.5 | Yes | 93 | Negative | Negative |

| #056 | 1.1 | Yes | Unknown | Negative | Negative |

| #057 | 3.3 | Yes | 10 | Negative | Negative |

| #059 | 2.8 | Yes | 25 | Negative | Negative |

| #060 | 0.5 | Yes | 64 | Negative | Negative |

| #061 | 1.4 | Yes | 370 | Negative | Negative |

| #062 | 0.6 | No | 107 | Positive | Negative |

| #064 | 1.4 | No | 323 | Negative | Negative |

| #065 | 0.4 | Yes | 14 | Positive | Negative |

| #066 | 2.3 | Yes | 186 | Positive | Negative |

| #067 | 7.2 | Yes | 946 | Negative | Negative |

| #069 | 0.5 | Yes | 30 | Positive | Negative |

| #070 | 5.6 | Yes | 76 | Negative | Negative |

| #071 | 1.9 | Yes | 81 | Negative | Negative |

| #073 | 0.6 | Yes | 50 | Positive | Negative |

| #074 | 0.5 | No | 65 | Negative | Negative |

| #075 | 6.6 | No | 2311 | Negative | Negative |

| #076 | 0.6 | No | 55 | Negative | Negative |

| #077 | 0.6 | Yes | 83 | Negative | Negative |

| #078 | 3.6 | Yes | 94 | Negative | Negative |

| #079 | 0.6 | Yes | 51 | Negative | Negative |

| #080 | 1.5 | Yes | 321 | Negative | Negative |

| #081 | 1.0 | Yes | 259 | Positive | Negative |

| #082 | 8.6 | Yes | 410 | Negative | Negative |

| #083 | 0.4 | No | 30 | Positive | Negative |

| #084 | 10.3 | Unknown | Unknown | Negative | Negative |

| #085 | 0.7 | Yes | 164 | Negative | Negative |

| #086 | 2.7 | Yes | 125 | Positive | Negative |

| #087 | 0.5 | No | 68 | Negative | Negative |

| #090 | 1.0 | Yes | 191 | Negative | Negative |

| #091 | 5.7 | Unknown | Unknown | Negative | Negative |

| #093 | 12.2 | Yes | 53 | Negative | Negative |

| #094 | 1.6 | Yes | 138 | Negative | Negative |

| #095 | 2.7 | Yes | 532 | Negative | Negative |

| #096 | 0.7 | No | - | Positive | Negative |

| #097 | 3.0 | No | 112 | Negative | Negative |

| #098 | 0.5 | No | 69 | Positive | Negative |

| #099 | 5.3 | Yes | 251 | Negative | Negative |

| #100 | 0.3 | No | 380 | Negative | Negative |

| #101 | 11.8 | Yes | 316 | Negative | Positive |

| #103 | 0.7 | Yes | 153 | Negative | Negative |

| #104 | 0.4 | Yes | 35 | Negative | Negative |

| #106 | 6.8 | Yes | 68 | Negative | Negative |

| #107 | 1.7 | No | 555 | Negative | Negative |

| #108 | 13.8 | Yes | 214 | Negative | Negative |

| #109 | 0.5 | Yes | 16 | negative | Negative |

| #110 | 0.5 | Yes | 488 | Negative | Positive |

| #111 | 0.9 | Yes | 133 | Positive | Negative |

| #112 | 0.6 | Yes | 95 | Positive | Negative |

| #113 | 9.5 | Yes | 492 | Negative | Negative |

| #114 | 2.3 | Yes | 60 | Negative | Negative |

| #115 | 0.5 | Yes | 75 | Negative | Negative |

| #117 | 0.6 | Yes | 102 | Negative | Negative |

| #118 | 5.8 | Yes | 275 | Negative | Negative |

| #119 | 0.5 | No | 76 | Positive | Negative |

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Dead |

| 10 | Severely diseased |

| 20 | Major changes in the general condition |

| 30 | Medium changes in the general condition |

| 40 | Minor changes in the general condition |

| 50 | Completely normal general condition |

References

- Pedersen, N.C. Virologic and immunologic aspects of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1987, 218, 529–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paltrinieri, S.; Giordano, A.; Stranieri, A.; Lauzi, S. Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) and coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19): Are they similar? Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 1786–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.Y.; Wang, Q.; Liang, X.Y.; Zhang, S.; Bao, D.; Zhao, H.; Li, S.B.; Wang, K.; Hu, G.X.; Gao, F.S. An updated review of feline coronavirus: Mind the two biotypes. Virus Res. 2023, 326, 199059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M.A. Feline Infectious Peritonitis: Update on Pathogenesis, Diagnostics, and Treatment. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2020, 50, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solikhah, T.I.; Agustin, Q.A.D.; Damaratri, R.A.; Siwi, D.A.F.; Rafi’uttaqi, G.N.; Hartadi, V.A.; Solikhah, G.P. A review of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection. Vet. World 2024, 17, 2417–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.G.; Perron, M.; Murakami, E.; Bauer, K.; Park, Y.; Eckstrand, C.; Liepnieks, M.; Pedersen, N.C. The nucleoside analog GS-441524 strongly inhibits feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) virus in tissue culture and experimental cat infection studies. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 219, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, N.C.; Perron, M.; Bannasch, M.; Montgomery, E.; Murakami, E.; Liepnieks, M.; Liu, H. Efficacy and safety of the nucleoside analog GS-441524 for treatment of cats with naturally occurring feline infectious peritonitis. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2019, 21, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addie, D.D.; Covell-Ritchie, J.; Jarrett, O.; Fosbery, M. Rapid Resolution of Non-Effusive Feline Infectious Peritonitis Uveitis with an Oral Adenosine Nucleoside Analogue and Feline Interferon Omega. Viruses 2020, 12, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, P.J.; Bannasch, M.; Thomasy, S.M.; Murthy, V.D.; Vernau, K.M.; Liepnieks, M.; Montgomery, E.; Knickelbein, K.E.; Murphy, B.; Pedersen, N.C. Antiviral treatment using the adenosine nucleoside analogue GS-441524 in cats with clinically diagnosed neurological feline infectious peritonitis. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2020, 34, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Novicoff, W.; Nadeau, J.; Evans, S. Unlicensed GS-441524-Like Antiviral Therapy Can Be Effective for at-Home Treatment of Feline Infectious Peritonitis. Animals 2021, 11, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, M.; Uemura, Y. Therapeutic Effects of Mutian(R) Xraphconn on 141 Client-Owned Cats with Feline Infectious Peritonitis Predicted by Total Bilirubin Levels. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krentz, D.; Zenger, K.; Alberer, M.; Felten, S.; Bergmann, M.; Dorsch, R.; Matiasek, K.; Kolberg, L.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Meli, M.L.; et al. Curing Cats with Feline Infectious Peritonitis with an Oral Multi-Component Drug Containing GS-441524. Viruses 2021, 13, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addie, D.D.; Silveira, C.; Aston, C.; Brauckmann, P.; Covell-Ritchie, J.; Felstead, C.; Fosbery, M.; Gibbins, C.; Macaulay, K.; McMurrough, J.; et al. Alpha-1 Acid Glycoprotein Reduction Differentiated Recovery from Remission in a Small Cohort of Cats Treated for Feline Infectious Peritonitis. Viruses 2022, 14, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.S.; Coggins, S.; Barker, E.N.; Gunn-Moore, D.; Jeevaratnam, K.; Norris, J.M.; Hughes, D.; Stacey, E.; MacFarlane, L.; O’Brien, C.; et al. Retrospective study and outcome of 307 cats with feline infectious peritonitis treated with legally sourced veterinary compounded preparations of remdesivir and GS-441524 (2020–2022). J. Feline Med. Surg. 2023, 25, 1098612X231194460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renner, K.A.; Cattin, R.; Kimble, B.; Munday, J.; White, A.; Coggins, S. Efficacy of oral remdesivir in treating feline infectious peritonitis: A prospective observational study of 29 cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2025, 27, 1098612X251335189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosaro, E.; Pires, J.; Castillo, D.; Murphy, B.G.; Reagan, K.L. Efficacy of Oral Remdesivir Compared to GS-441524 for Treatment of Cats with Naturally Occurring Effusive Feline Infectious Peritonitis: A Blinded, Non-Inferiority Study. Viruses 2023, 15, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coggins, S.J.; Norris, J.M.; Malik, R.; Govendir, M.; Hall, E.J.; Kimble, B.; Thompson, M.F. Outcomes of treatment of cats with feline infectious peritonitis using parenterally administered remdesivir, with or without transition to orally administered GS-441524. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2023, 37, 1772–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokalsing, E.; Ferrolho, J.; Gibson, M.S.; Vilhena, H.; Anastacio, S. Efficacy of GS-441524 for Feline Infectious Peritonitis: A Systematic Review (2018–2024). Pathogens 2025, 14, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černá, P.; Ayoob, A.; Baylor, C.; Champagne, E.; Hazanow, S.; Heidel, R.E.; Wirth, K.; Legendre, A.M.; Gunn-Moore, D.A. Retrospective Survival Analysis of Cats with Feline Infectious Peritonitis Treated with Polyprenyl Immunostimulant That Survived over 365 Days. Pathogens 2022, 11, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hök, K. Morbidity, mortality and coronavirus antigen in previously coronavirus free kittens placed in two catteries with feline infectious peritonitis. Acta Vet. Scand. 1993, 34, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, N.M.; Miller, A.D.; Whittaker, G.R. Feline infectious peritonitis virus-associated rhinitis in a cat. JFMS Open Rep. 2020, 6, 2055116920930582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchta, K.; Zuzzi-Krebitz, A.-M.; Bergmann, M.; Dorsch, R.; Zwicklbauer, K.; Matiasek, K.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Meli, M.L.; Spiri, A.M.; Zablotski, Y.; et al. Unexpected Clinical and Laboratory Observations During and After 42-Day Versus 84-Day Treatment with Oral GS-441524 in Cats with Feline Infectious Peritonitis with Effusion. Viruses 2025, 17, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Hosie, M.J.; Hartmann, K.; Egberink, H.; Truyen, U.; Tasker, S.; Belák, S.; Boucraut-Baralon, C.; Frymus, T.; Lloret, A.; et al. Calicivirus Infection in Cats. Viruses 2022, 14, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, A.; Willi, B.; Meli, M.L.; Boretti, F.S.; Hartnack, S.; Dreyfus, A.; Lutz, H.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. Feline calicivirus and other respiratory pathogens in cats with Feline calicivirus-related symptoms and in clinically healthy cats in Switzerland. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, W.A.; Soltero-Rivera, M.; Ramesh, A.; Lommer, M.J.; Arzi, B.; DeRisi, J.L.; Horst, J.A. Use of unbiased metagenomic and transcriptomic analyses to investigate the association between feline calicivirus and feline chronic gingivostomatitis in domestic cats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2021, 82, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgard, S.; Truyen, U.; Thibault, J.C.; Sauter-Louis, C.; Hartmann, K. Relevance of feline calicivirus, feline immunodeficiency virus, feline leukemia virus, feline herpesvirus and Bartonella henselae in cats with chronic gingivostomatitis. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2010, 123, 369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, J.O.; McArdle, F.; Dawson, S.; Carter, S.D.; Gaskell, C.J.; Gaskell, R.M. Studies on the role of feline calicivirus in chronic stomatitis in cats. Vet. Microbiol. 1991, 27, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehl, T.; Bleiholder, A.; Rossmann, F.; Rupp, S.; Lei, J.; Lee, J.; Boyce, W.; Vickers, W.; Crooks, K.; Vandewoude, S.; et al. Complete Genome Sequences of Two Novel Puma concolor Foamy Viruses from California. Genome Announc. 2013, 1, e0020112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraberger, S.; Fountain-Jones, N.M.; Gagne, R.B.; Malmberg, J.; Dannemiller, N.G.; Logan, K.; Alldredge, M.; Varsani, A.; Crooks, K.R.; Craft, M.; et al. Frequent cross-species transmissions of foamy virus between domestic and wild felids. Virus Evol. 2020, 6, vez058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleiholder, A.; Mühle, M.; Hechler, T.; Bevins, S.; vandeWoude, S.; Denner, J.; Löchelt, M. Pattern of seroreactivity against feline foamy virus proteins in domestic cats from Germany. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2011, 143, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linial, M. Why aren’t foamy viruses pathogenic? Trends Microbiol. 2000, 8, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.; Rudolph, W.; Juretzek, T.; Gärtner, K.; Bock, M.; Herchenröder, O.; Lindemann, D.; Heinkelein, M.; Rethwilm, A. Feline foamy virus genome and replication strategy. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 11324–11331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechejian, S.; Dannemiller, N.; Kraberger, S.; Ledesma Feliciano, C.; Lochelt, M.; Carver, S.; VandeWoude, S. Feline foamy virus seroprevalence and demographic risk factors in stray domestic cat populations in Colorado, Southern California and Florida, USA. JFMS Open Rep. 2019, 5, 2055116919873736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcante, L.T.F.; Muniz, C.P.; Jia, H.; Augusto, A.M.; Troccoli, F.; Medeiros, S.O.; Dias, C.G.A.; Switzer, W.M.; Soares, M.A.; Santos, A.F. Clinical and Molecular Features of Feline Foamy Virus and Feline Leukemia Virus Co-Infection in Naturally-Infected Cats. Viruses 2018, 10, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German, A.C.; Harbour, D.A.; Helps, C.R.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.J. Is feline foamy virus really apathogenic? Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008, 123, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenger, E.; Brown, W.C.; Song, W.; Wolf, A.M.; Pedersen, N.C.; Longnecker, M.; Li, J.; Collisson, E.W. Evaluation of cofactor effect of feline syncytium-forming virus on feline immunodeficiency virus infection. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1993, 54, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, T.; Ikeda, Y.; Maeda, K.; Horimoto, T.; Tohya, Y.; Mochizuki, M.; Vu, D.; Vu, G.D.; Cu, D.X.; Ono, K.; et al. Seroepidemiological survey of feline retrovirus infections in domestic and leopard cats in northern Vietnam in 1997. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1998, 60, 1273–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, I.G.; Löchelt, M.; Flower, R.L. Epidemiology of feline foamy virus and feline immunodeficiency virus infections in domestic and feral cats: A seroepidemiological study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999, 37, 2848–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Miyazawa, T.; Ikeda, Y.; Sato, E.; Nishimura, Y.; Nguyen, N.T.; Takahashi, E.; Mochizuki, M.; Mikami, T. Contrastive prevalence of feline retrovirus infections between northern and southern Vietnam. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2000, 62, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romen, F.; Pawlita, M.; Sehr, P.; Bachmann, S.; Schröder, J.; Lutz, H.; Löchelt, M. Antibodies against Gag are diagnostic markers for feline foamy virus infections while Env and Bet reactivity is undetectable in a substantial fraction of infected cats. Virology 2006, 345, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedal, G.; Toresson, L.; Nehring, M.; Hawley, J.; Vande Woude, S.; Lappin, M. Prevalence of selected infectious agents in Swedish cats with fever and/or anemia compared to cats without fever and/or anemia and to stable/stray cats. Acta Vet. Scand. 2025, 67, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, B.T.; Oğuzoğlu, T. First report on the prevalence and genetic relatedness of Feline Foamy Virus (FFV) from Turkish domestic cats. Virus Res. 2019, 274, 197768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Hartmann, K. Feline leukaemia virus infection: A practical approach to diagnosis. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2020, 22, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, N.; Lutz, H.; Saegerman, C.; Gönczi, E.; Meli, M.L.; Boo, G.; Hartmann, K.; Hosie, M.J.; Moestl, K.; Tasker, S.; et al. Pan-European Study on the Prevalence of the Feline Leukaemia Virus Infection—Reported by the European Advisory Board on Cat Diseases (ABCD Europe). Viruses 2019, 11, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorio, A.P.; Franti, C.E.; Madewell, B.R.; Pedersen, N.C. Chronic oral infections of cats and their relationship to persistent oral carriage of feline calici-, immunodeficiency, or leukemia viruses. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1991, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Berger, M.; Sigrist, B.; Schawalder, P.; Lutz, H. Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) infection leads to increased incidence of feline odontoclastic resorptive lesions (FORL). Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1998, 65, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macieira, D.B.; de Menezes Rde, C.; Damico, C.B.; Almosny, N.R.; McLane, H.L.; Daggy, J.K.; Messick, J.B. Prevalence and risk factors for hemoplasmas in domestic cats naturally infected with feline immunodeficiency virus and/or feline leukemia virus in Rio de Janeiro-Brazil. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2008, 10, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poland, A.M.; Vennema, H.; Foley, J.E.; Pedersen, N.C. Two related strains of feline infectious peritonitis virus isolated from immunocompromised cats infected with a feline enteric coronavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996, 34, 3180–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasker, S. Diagnosis of feline infectious peritonitis: Update on evidence supporting available tests. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2018, 20, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyadee, W.; Chiteafea, N.; Tuanthap, S.; Choowongkomon, K.; Roytrakul, S.; Rungsuriyawiboon, O.; Boonkaewwan, C.; Tansakul, N.; Rattanasrisomporn, A.; Rattanasrisomporn, J. The first study on clinicopathological changes in cats with feline infectious peritonitis with and without retrovirus coinfection. Vet. World 2023, 16, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasker, S.; Addie, D.D.; Egberink, H.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Hosie, M.J.; Truyen, U.; Belák, S.; Boucraut-Baralon, C.; Frymus, T.; Lloret, A.; et al. Feline Infectious Peritonitis: European Advisory Board on Cat Diseases Guidelines. Viruses 2023, 15, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.; Barrs, V.R.; Kelman, M.; Ward, M.P. Feline upper respiratory tract infection and disease in Australia. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2019, 21, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, E.C.; Tse, T.Y.; Oates, A.W.; Jackson, K.; Pfeiffer, S.; Donahoe, S.L.; Setyo, L.; Barrs, V.R.; Beatty, J.A.; Pesavento, P.A. Oropharyngeal Shedding of Gammaherpesvirus DNA by Cats, and Natural Infection of Salivary Epithelium. Viruses 2022, 14, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennington, M.R.; Fort, M.W.; Ledbetter, E.C.; Van de Walle, G.R. A novel corneal explant model system to evaluate antiviral drugs against feline herpesvirus type 1 (FHV-1). J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Z.; Han, X.H.; Yao, L.Q.; Zhang, W.K.; Liu, B.S.; Chen, Z.L. Development and application of a simple recombinase polymerase amplification assay for rapid point-of-care detection of feline herpesvirus type 1. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monne Rodriguez, J.M.; Leeming, G.; Kohler, K.; Kipar, A. Feline Herpesvirus Pneumonia: Investigations Into the Pathogenesis. Vet. Pathol. 2017, 54, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Chen, Q.; Ye, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Jin, J.; Cao, S.; et al. Epidemiological survey of feline viral infectious diseases in China from 2018 to 2020. Anim. Res. One Health 2023, 1, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zicola, A.; Saegerman, C.; Quatpers, D.; Viandier, J.; Thiry, E. Feline herpesvirus 1 and feline calicivirus infections in a heterogeneous cat population of a rescue shelter. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11, 1023–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurissio, J.K.; Rodrigues, M.V.; Taniwaki, S.A.; Zanutto, M.D.S.; Filoni, C.; Galdino, M.V.; Araújo Júnior, J.P. Felis catus gammaherpesvirus 1 (FcaGHV1) and coinfections with feline viral pathogens in domestic cats in Brazil. Ciência Rural 2018, 48, e20170480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLuckie, A.J.; Barrs, V.R.; Wilson, B.; Westman, M.E.; Beatty, J.A. Felis Catus Gammaherpesvirus 1 DNAemia in Whole Blood from Therapeutically Immunosuppressed or Retrovirus-Infected Cats. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novacco, M.; Kohan, N.R.; Stirn, M.; Meli, M.L.; Diaz-Sanchez, A.A.; Boretti, F.S.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. Prevalence, Geographic Distribution, Risk Factors and Co-Infections of Feline Gammaherpesvirus Infections in Domestic Cats in Switzerland. Viruses 2019, 11, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, R.; Korb, M.; Langbein-Detsch, I.; Klein, D. Prevalence and risk factors of gammaherpesvirus infection in domestic cats in Central Europe. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, J.A.; Troyer, R.M.; Carver, S.; Barrs, V.R.; Espinasse, F.; Conradi, O.; Stutzman-Rodriguez, K.; Chan, C.C.; Tasker, S.; Lappin, M.R.; et al. Felis catus gammaherpesvirus 1; a widely endemic potential pathogen of domestic cats. Virology 2014, 460–461, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasco, M.C.; Iacomino, N.; Mantegazza, R.; Cavalcante, P. COVID-19, Epstein-Barr virus reactivation and autoimmunity: Casual or causal liaisons? J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2025, 58, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberer, M.; von Both, U. Cats and kids: How a feline disease may help us unravel COVID-19 associated paediatric hyperinflammatory syndrome? Infection 2021, 49, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetzke, C.C.; Massoud, M.; Frischbutter, S.; Guerra, G.M.; Ferreira-Gomes, M.; Heinrich, F.; von Stuckrad, A.S.L.; Wisniewski, S.; Licha, J.R.; Bondareva, M.; et al. TGFbeta links EBV to multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Nature 2025, 640, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fear Free Leaders in Animal Wellbeing. Available online: https://fearfreepets.com/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Spiri, A.M.; Zwicklbauer, K.; Meunier, S.M.; Felten, S.; Unterer, S.; Meli, M.L.; Wenk, J.; de Witt Curtius, C.C.; Stachowski, J.M.; Crespo Bouzon, A.; et al. Confirmation: 42 Days of GS-441524 Sufficient to Efficaciously Treat All Forms of Feline Infectious Peritonitis in Cats. In Manuscript in preparation.

- Swiss Association for Small Animal Medicine, Vaccination Guidelines of SVK-ASMPA 2022. Available online: https://svk-asmpa.ch/wp-content/uploads/impfempfehlungen-svk-asmpa.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- ABCD Vaccine Recommendations. Available online: https://www.abcdcatsvets.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Vaccine-recommendations_2025_EN.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Williams, J.L.; Roberts, C.; Harley, R.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.J.; Murray, J.K. Prevalence and risk factors for gingivitis in a cohort of UK companion cats aged up to 6 years. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2024, 65, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, K.; Kuffer, M. Karnofsky’s score modified for cats. Eur. J. Med. Res. 1998, 3, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ginders, J.; Stirn, M.; Novacco, M.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Riond, B. Validation of the Sysmex XN-V Automated Nucleated Red Blood Cell Enumeration for Canine and Feline EDTA-Anticoagulated Blood. Animals 2024, 14, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfer-Hungerbuehler, A.K.; Spiri, A.M.; Meili, T.; Riond, B.; Krentz, D.; Zwicklbauer, K.; Buchta, K.; Zuzzi-Krebitz, A.M.; Hartmann, K.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; et al. Alpha-1-Acid Glycoprotein Quantification via Spatial Proximity Analyte Reagent Capture Luminescence Assay: Application as Diagnostic and Prognostic Marker in Serum and Effusions of Cats with Feline Infectious Peritonitis Undergoing GS-441524 Therapy. Viruses 2024, 16, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meli, M.L.; Berger, A.; Willi, B.; Spiri, A.M.; Riond, B.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. Molecular detection of feline calicivirus in clinical samples: A study comparing its detection by RT-qPCR directly from swabs and after virus isolation. J. Virol. Methods 2018, 251, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gut, M.; Leutenegger, C.M.; Huder, J.B.; Pedersen, N.C.; Lutz, H. One-tube fluorogenic reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for the quantitation of feline coronaviruses. J. Virol. Methods 1999, 77, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meli, M.L.; Spiri, A.M.; Zwicklbauer, K.; Krentz, D.; Felten, S.; Bergmann, M.; Dorsch, R.; Matiasek, K.; Alberer, M.; Kolberg, L.; et al. Fecal Feline Coronavirus RNA Shedding and Spike Gene Mutations in Cats with Feline Infectious Peritonitis Treated with GS-441524. Viruses 2022, 14, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, R.; Cattori, V.; Gomes-Keller, M.A.; Meli, M.L.; Golder, M.C.; Lutz, H.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. Quantitation of feline leukaemia virus viral and proviral loads by TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction. J. Virol. Methods 2005, 130, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helps, C.; Lait, P.; Tasker, S.; Harbour, D. Melting curve analysis of feline calicivirus isolates detected by real-time reverse transcription PCR. J. Virol. Methods 2002, 106, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Eldaim, M.M.; Wilkes, R.P.; Thomas, K.V.; Kennedy, M.A. Development and validation of a TaqMan real-time reverse transcription-PCR for rapid detection of feline calicivirus. Arch. Virol. 2009, 154, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogtlin, A.; Fraefel, C.; Albini, S.; Leutenegger, C.M.; Schraner, E.; Spiess, B.; Lutz, H.; Ackermann, M. Quantification of feline herpesvirus 1 DNA in ocular fluid samples of clinically diseased cats by real-time TaqMan PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willi, B.; Spiri, A.M.; Meli, M.L.; Samman, A.; Hoffmann, K.; Sydler, T.; Cattori, V.; Graf, F.; Diserens, K.A.; Padrutt, I.; et al. Molecular characterization and virus neutralization patterns of severe, non-epizootic forms of feline calicivirus infections resembling virulent systemic disease in cats in Switzerland and in Liechtenstein. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 182, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, R.M.; Beatty, J.A.; Stutzman-Rodriguez, K.R.; Carver, S.; Lozano, C.C.; Lee, J.S.; Lappin, M.R.; Riley, S.P.; Serieys, L.E.; Logan, K.A.; et al. Novel gammaherpesviruses in North American domestic cats, bobcats, and pumas: Identification, prevalence, and risk factors. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 3914–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thermofisher Essentials of Real Time PCR. Available online: https://commerce.thermofisher.com/content/dam/LifeTech/migration/en/filelibrary/nucleic-acid-amplification-expression-profiling/pdfs.par.65119.file.dat/essentials%20of%20real%20time%20pcr.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Zhao, F.; Maren, N.A.; Kosentka, P.Z.; Liao, Y.Y.; Lu, H.; Duduit, J.R.; Huang, D.; Ashrafi, H.; Zhao, T.; Huerta, A.I.; et al. An optimized protocol for stepwise optimization of real-time RT-PCR analysis. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, H.; Pedersen, N.C.; Theilen, G.H. Course of feline leukemia virus infection and its detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and monoclonal antibodies. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1983, 44, 2054–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Tandon, R.; Boretti, F.S.; Meli, M.L.; Willi, B.; Cattori, V.; Gomes-Keller, M.A.; Ossent, P.; Golder, M.C.; Flynn, J.N.; et al. Reassessment of feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) vaccines with novel sensitive molecular assays. Vaccine 2006, 24, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzolari, M.; Young, E.; Cox, D.; Davis, D.; Lutz, H. Serological diagnosis of feline immunodeficiency virus infection using recombinant transmembrane glycoprotein. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1995, 46, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egberink, H.F.; Lutz, H.; Horzinek, M.C. Use of western blot and radioimmunoprecipitation for diagnosis of feline leukemia and feline immunodeficiency virus infections. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1991, 199, 1339–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, H.; Arnold, P.; Hübscher, U.; Egberink, H.; Pedersen, N.; Horzinek, M.C. Specificity assessment of feline T-lymphotropic lentivirus serology. Zentralbl Vet. B 1988, 35, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenfeld, J.; Meili, T.; Meli, M.L.; Riond, B.; Helfer-Hungerbuehler, A.K.; Bönzli, E.; Pineroli, B.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. Decreased Sensitivity of the Serological Detection of Feline Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Potentially Due to Imported Genetic Variants. Viruses 2019, 11, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Witt Curtius, C.C.; Rodary, M.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Spiri, A.M.; Meli, M.L.; Crespo Bouzon, A.; Wenk, J.; Cerchiaro, I.; Pineroli, B.; Pot, S.A.; et al. Navigating Neurological Re-emergence in Feline Infectious Peritonitis: Challenges and Insights from GS-441524 and Remdesivir Treatment. J. Feline Med. Surg. Open Rep. 2025, 11, 20551169251360625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, N.; Servet, E.; Biourge, V.; Hennet, P. Periodontal health status in a colony of 109 cats. J. Vet. Dent. 2009, 26, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.; Manzanilla, E.G.; Lloret, A.; Leon, M.; Thibault, J.C. Prevalence of feline herpesvirus-1, feline calicivirus, Chlamydophila felis and Mycoplasma felis DNA and associated risk factors in cats in Spain with upper respiratory tract disease, conjunctivitis and/or gingivostomatitis. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2017, 19, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Yang, M.; Du, J.; Wang, K.; Chen, R.; Feng, X.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X. Epidemiological investigation of feline chronic gingivostomatitis and its relationship with oral microbiota in Xi’an, China. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1418101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, N.C. Inflammatory oral cavity diseases of the cat. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 1992, 22, 1323–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, R.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.J.; Day, M.J. Salivary and serum immunoglobulin levels in cats with chronic gingivostomatitis. Vet. Rec. 2003, 152, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arzi, B.; Mills-Ko, E.; Verstraete, F.J.; Kol, A.; Walker, N.J.; Badgley, M.R.; Fazel, N.; Murphy, W.J.; Vapniarsky, N.; Borjesson, D.L. Therapeutic Efficacy of Fresh, Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Severe Refractory Gingivostomatitis in Cats. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2016, 5, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lommer, M.J. Oral inflammation in small animals. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2013, 43, 555–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phongroop, K.; Rattanasrisomporn, J.; Piewbang, C.; Tangtrongsup, S.; Rungsipipat, A.; Techangamsuwan, S. Molecular epidemiology and strain diversity of circulating feline Calicivirus in Thai cats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1377327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskell, R.M.; Povey, R.C. Experimental induction of feline viral rhinotracheitis virus re-excretion in FVR-recovered cats. Vet. Rec. 1977, 100, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskell, R.M.; Povey, R.C. Transmission of feline viral rhinotracheitis. Vet. Rec. 1982, 111, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, N.C.; Sato, R.; Foley, J.E.; Poland, A.M. Common virus infections in cats, before and after being placed in shelters, with emphasis on feline enteric coronavirus. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2004, 6, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, T.M. Feline respiratory virus carriers in clinically healthy cats. Aust. Vet. J. 1981, 57, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABCD ABCD Guideline for Feline Herpesvirus Infection. Available online: https://www.abcdcatsvets.org/guideline-for-feline-herpesvirus-infection/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Schulz, C.; Hartmann, K.; Mueller, R.S.; Helps, C.; Schulz, B.S. Sampling sites for detection of feline herpesvirus-1, feline calicivirus and Chlamydia felis in cats with feline upper respiratory tract disease. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2015, 17, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABCD Guideline for Feline Leukaemia Virus Infection. Available online: https://www.abcdcatsvets.org/guideline-for-feline-leukaemia-virus-infection/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- ABCD Guideline for Feline Immunodeficiency Virus. Available online: https://www.abcdcatsvets.org/guideline-for-feline-immunodeficiency-virus/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Gönczi, E.; Riond, B.; Meli, M.; Willi, B.; Howard, J.; Schaarschmidt-Kiener, D.; Regli, W.; Gilli, U.; Boretti, F. Feline leukemia virus infection: Importance and current situation in Switzerland. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2018, 160, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, H.; Lehmann, R.; Winkler, G.; Kottwitz, B.; Dittmer, A.; Wolfensberger, C.; Arnold, P. Feline immunodeficiency virus in Switzerland: Clinical aspects and epidemiology in comparison with feline leukemia virus and coronaviruses. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 1990, 132, 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Moyadee, W.; Sunpongsri, S.; Choowongkomon, K.; Roytrakul, S.; Rattanasrisomporn, A.; Tansakul, N.; Rattanasrisomporn, J. Feline infectious peritonitis: A comprehensive evaluation of clinical manifestations, laboratory diagnosis, and therapeutic approaches. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2024, 11, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Hong, X.; Zhang, T. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) in Mainland China between 2008 and 2023: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Animals 2024, 14, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenchenkova, A.P.; Makarov, V.V. Prevalence, haematological, biochemical abnormalities and clinical syndromes of FeLV and FeLV/FIV co-infected among cat population in Moscow and the Moscow region, Russia. Bulg. J. Vet. Med. 2023, 26, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma-Feliciano, C.; Troyer, R.M.; Zheng, X.; Miller, C.; Cianciolo, R.; Bordicchia, M.; Dannemiller, N.; Gagne, R.; Beatty, J.; Quimby, J.; et al. Feline Foamy Virus Infection: Characterization of Experimental Infection and Prevalence of Natural Infection in Domestic Cats with and without Chronic Kidney Disease. Viruses 2019, 11, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alke, A.; Schwantes, A.; Zemba, M.; Flugel, R.M.; Lochelt, M. Characterization of the humoral immune response and virus replication in cats experimentally infected with feline foamy virus. Virology 2000, 275, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissl, K.; Benetka, V.; Schachner, E.; Tichy, A.; Latif, M.; Mayrohofer, E.; Möstl, K. Osteoarthritis in cats and the possible involvement of feline Calicivirus and feline Retroviruses. Wien. Tierärztliche Wochenschr. 2012, 99, 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, N.C. Feline syncytium-forming virus infection. In Diseases of the Cat; Holzworth, J., Ed.; The W. B. Saunder Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1986; pp. 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, H.; Madadgar, O.; Jamshidi, S.; Ghalyanchi Langeroudi, A.; Darzi Lemraski, M. Molecular and clinical study on prevalence of feline herpesvirus type 1 and calicivirus in correlation with feline leukemia and immunodeficiency viruses. Vet. Res. Forum 2014, 5, 255–261. [Google Scholar]

- LaVigne, E.K.; Levy, N.E.; Bardzinski, A.R.; Scaletti, F.; Horecka, K.; Cuccinello, M.K.; Moore, D.M.; Levy, J.K. Spectrum of care approach to animal shelter management of feline infectious peritonitis complicated by feline leukemia virus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1570267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABCD FIP Diagnostic Tool. Available online: https://www.abcdcatsvets.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/TOOL_FIP_Feline_infectious_peritonitis_December_2021_EN.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

| Virus | Target | Material | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPC | Blood | ||

| Feline coronavirus (FCoV) | Viral RNA | x | x |

| Feline calicivirus (FCV) | Viral RNA | x | |

| Feline foamy virus (FFV) | Viral RNA | x | |

| Proviral DNA | x | ||

| Feline leukemia virus (FeLV) | Viral RNA | x | x |

| Proviral DNA | x | ||

| Feline herpesvirus (FHV) | Viral DNA | x | |

| Feline gammaherpesvirus (FcaGHV1) | Viral DNA | x | |

| Virus | Method | Target Gene | Amplicon Size (bp) | Forward Primer, Reverse Primer, Probe IDs | Concentration (nM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCoV | RT-qPCR | Orf 7b | 103 | FCoV1 (1147), FCoV2 (1072), FCoVp | 900/300/300 | [76,77] |

| FeLV | RT-qPCR, qPCR | FeLV LTR U3 | 131 | exoFeLV-U3F2, exoFeLV-U3R2, exoFeLVU3p | 900/300/200 | [44,78] |

| FCV S1 | RT-qPCR | Orf1 (polymerase) | 95 | FCV.forw, FCV.rev, FCV.p | 300/900/250 | [24,75,79] |

| FCV S2 | RT-qPCR | Orf1 (polymerase) | 120 | FCV.1f, FCV.120r, FCV.26p | 300/900/250 | [75,80] |

| FHV | qPCR | Glyco- protein B | 81 | FHV.351f, FHV.431r, FHV.376p | 400/400/80 | [81,82] |

| FcaGHV1 | qPCR | Glyco- protein B | 113 | FGHVF3, FGHVR3, FGHVP3 | 900/900/250 | [61,83] |

| FFV | RT-qPCR, qPCR | gag | 91 | PFFV.2584f, PFFV.2674r, PFFV.2617p | 300/900/250, 900/900/250 | Newly established |

| Virus | Prevalence (95% CI) [%] | Median Load OPC (Range) [Copies/OPC Sample] | Median Load Blood (Range) [Copies/mL Blood] |

|---|---|---|---|

| FCoV | 36 (26.5–45.6) | 5.4 × 102 (1.7 × 101–2.0 × 106) | n.a. |

| FCV | 28 (19.2–37.9) | 2.1 × 105 (1.1 × 100–9.8 × 106) | n.a. |

| FFV | 23 (14.8–32.3) | Provirus OPC: 6.2 × 101 (1.0 × 100–6.1 × 103) RNA OPC: 3.6 × 105 (2.0 × 100–1.5 × 107) | n.a. |

| FHV | 6 (2.3–13.0) | 2.5 × 101 (1.1 × 101–1.4 × 104) | n.a. |

| FIV | 4 (1.1–9.9) | n.a | n.a |

| FeLV | 2 (0.2–7.0) | RNA OPC: 6.8 × 107 and 1.4 × 108 | Provirus blood: 3.6 × 108 and 8.7 × 107 RNA blood 1.4 × 109 and 2.2 × 109 |

| FcaGHV1 | 2 (0.2–7.0) | n.a. | 1.6 × 102 and 1.2 × 103 |

| Cat ID | Age (Years) | Clinician Score | FCGS (Grade) | FCoV Oral | FCV | FFV | FeLV | FIV | FHV | FcaGHV1 | Number of Coinfections * | Origin of Cat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #001 | 1.8 | 20 | 0 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | (0) | CH | |||

| #002 | 1.7 | 40 | 3 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | (0) | ES | |||

| #003 | 3.4 | 30 | 0 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | (0) | CH | |||

| #004 | 0.8 | 40 | 1 | 2 | BY | |||||||

| #006 | 5.2 | 30 | 1 | 1 | DE | |||||||

| #007 | 1.3 | 10 | 4 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #008 | 0.8 | 40 | 0 | 1 | AE | |||||||

| #009 | 1.1 | 40 | 0 | 0 | DE | |||||||

| #010 | 4.1 | 50 | 2 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #011 | 0.6 | 40 | 0 | 0 | SV | |||||||

| #012 | 0.7 | 40 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #013 | 0.9 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #015 | 1.1 | 50 | 1 | 2 | CY | |||||||

| #017 | 10.3 | 10 | 2 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #018 | 1.8 | 50 | 1 | 1 | ES | |||||||

| #022 | 0.3 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #023 | 7.8 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #024 | 1.3 | 40 | 1 | 0 | ES | |||||||

| #025 | 1.4 | 40 | 1 | 2 | RU | |||||||

| #027 | 1.1 | 30 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #028 | 0.7 | 50 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #029 | 1.2 | 30 | 0 | 0 | SK | |||||||

| #031 | 5.8 | 30 | 4 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #033 | 0.5 | 40 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #034 | 7.3 | 40 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #035 | 7.3 | 20 | 2 | 2 | AT | |||||||

| #036 | 2.6 | 20 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #037 | 0.6 | 10 | 0 | 2 | CH | |||||||

| #038 | 7.3 | 40 | 1 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #039 | 12.3 | 40 | 3 | 3 | CH | |||||||

| #040 | 0.4 | 30 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #041 | 4.5 | 10 | n.k. | 0 | n.k. | |||||||

| #042 | 0.4 | 30 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #043 | 0.5 | 40 | 0 | 0 | DE | |||||||

| #044 | 0.9 | 40 | 0 | 0 | DE | |||||||

| #045 | 0.5 | 30 | 1 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #046 | 3.1 | 40 | 1 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #047 | 3.0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #048 | 13.0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | BR | |||||||

| #049 | 8.0 | 20 | 0 | 3 | CH | |||||||

| #050 | 1.2 | 30 | 0 | 0 | FR | |||||||

| #051 | 4.1 | 40 | 0 | 3 | CH | |||||||

| #052 | 0.4 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #053 | 0.4 | 40 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #054 | 1.3 | 40 | 0 | 2 | ES | |||||||

| #055 | 2.5 | 10 | n.k. | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #056 | 1.1 | 40 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #057 | 3.3 | 40 | 0 | 0 | IT | |||||||

| #059 | 2.8 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #060 | 0.5 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #061 | 1.4 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #062 | 0.6 | 20 | 3 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #064 | 1.4 | 10 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #065 | 0.4 | 30 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #066 | 2.3 | 30 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #067 | 7.2 | 40 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #069 | 0.5 | 20 | 0 | 1 | GR | |||||||

| #070 | 5.6 | 30 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #071 | 1.9 | 30 | 0 | 0 | LV | |||||||

| #073 | 0.6 | 50 | 1 | 1 | DE | |||||||

| #074 | 0.5 | 30 | 0 | 1 | DE | |||||||

| #075 | 6.6 | 40 | 3 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #076 | 0.6 | 30 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #077 | 0.6 | 30 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #078 | 3.6 | 30 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #079 | 0.6 | 30 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #080 | 1.5 | 40 | 3 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #081 | 1.0 | 10 | 4 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #082 | 8.6 | 20 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #083 | 0.4 | 20 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #084 | 10.3 | 10 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #085 | 0.7 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #086 | 2.7 | 30 | 0 | 3 | SK | |||||||

| #087 | 0.5 | 30 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #090 | 1.0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #091 | 5.7 | 10 | n.k. | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #093 | 12.2 | 20 | 0 | 0 | n.k. | |||||||

| #094 | 1.6 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #095 | 2.7 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #096 | 0.7 | 30 | 1 | 1 | n.k. | |||||||

| #097 | 3.0 | 40 | 0 | 2 | CH | |||||||

| #098 | 0.5 | 30 | 1 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #099 | 5.3 | 50 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #100 | 0.3 | 30 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #101 | 11.8 | 40 | 0 | 2 | CH | |||||||

| #103 | 0.7 | 40 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #104 | 0.4 | 40 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #106 | 6.8 | 30 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #107 | 1.7 | 30 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #108 | 13.8 | 40 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #109 | 0.5 | 20 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #110 | 0.5 | 30 | 0 | 2 | CH | |||||||

| #111 | 0.9 | 40 | 0 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #112 | 0.6 | 40 | 1 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| #113 | 9.5 | 30 | 0 | 0 | RO | |||||||

| #114 | 2.3 | 40 | 0 | 0 | SK | |||||||

| #115 | 0.5 | 40 | 0 | 0 | DE | |||||||

| #117 | 0.6 | 30 | 0 | 0 | DE | |||||||

| #118 | 5.8 | 50 | 0 | 0 | CH | |||||||

| #119 | 0.5 | 40 | 1 | 1 | CH | |||||||

| <2 years old | FCGS grade 0 (absent) | |||||||||||

| ≥2 years old | FCGS grade 1 | |||||||||||

| Clinician Score 10 | FCGS grade 2 | |||||||||||

| Clinician Score 20 | FCGS grade 3 | |||||||||||

| Clinician Score 30 | FCGS grade 4 | |||||||||||

| Clinician Score 40 | No coinfection | |||||||||||

| Clinician Score 50 | 1 coinfection | |||||||||||

| (RT)-qPCR positive | 2 coinfections | |||||||||||

| (RT)-qPCR negative | 3 coinfections | |||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wenk, J.; Meli, M.L.; Meunier, S.M.; Felten, S.; de Witt Curtius, C.C.; Crespo Bouzon, A.; Cerchiaro, I.; Pineroli, B.; Kipar, A.; Unterer, S.; et al. Viral Coinfections Potentially Associated with Feline Chronic Gingivostomatitis in Cats with Feline Infectious Peritonitis. Viruses 2025, 17, 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111505

Wenk J, Meli ML, Meunier SM, Felten S, de Witt Curtius CC, Crespo Bouzon A, Cerchiaro I, Pineroli B, Kipar A, Unterer S, et al. Viral Coinfections Potentially Associated with Feline Chronic Gingivostomatitis in Cats with Feline Infectious Peritonitis. Viruses. 2025; 17(11):1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111505

Chicago/Turabian StyleWenk, Jennifer, Marina L. Meli, Solène M. Meunier, Sandra Felten, Celia C. de Witt Curtius, Aline Crespo Bouzon, Ilaria Cerchiaro, Benita Pineroli, Anja Kipar, Stefan Unterer, and et al. 2025. "Viral Coinfections Potentially Associated with Feline Chronic Gingivostomatitis in Cats with Feline Infectious Peritonitis" Viruses 17, no. 11: 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111505

APA StyleWenk, J., Meli, M. L., Meunier, S. M., Felten, S., de Witt Curtius, C. C., Crespo Bouzon, A., Cerchiaro, I., Pineroli, B., Kipar, A., Unterer, S., Zwicklbauer, K., Hartmann, K., Hofmann-Lehmann, R., & Spiri, A. M. (2025). Viral Coinfections Potentially Associated with Feline Chronic Gingivostomatitis in Cats with Feline Infectious Peritonitis. Viruses, 17(11), 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111505