Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged the rapid development and licensing of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Currently, numerous vaccines are available on a global scale and are based on different mechanisms of action, including mRNA technology, viral vectors, inactive viruses, and subunit particles. Mass vaccination conducted worldwide has highlighted the potential development of side effects, including ones with skin involvement. This review synthesizes data from 62 manuscripts, reporting a total of 142 cases of autoimmune blistering skin diseases (AIBDs) following COVID-19 vaccination, comprising 59 cases of pemphigus and 83 cases of bullous pemphigoid. Among the 83 bullous pemphigoid cases, 78 were BP, with additional cases including 2 oral mucous membrane pemphigoid, 1 pemphigoid gestationis, 1 anti-p200 BP, and 1 dyshidrosiform BP. The mean age of affected individuals was 72 ± 12.7 years, with an average symptom onset of 11 ± 10.8 days post-vaccination. Notably, 59% of cases followed vaccination with BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech), 51.8% were new diagnoses, and 45.8% occurred after the second dose. The purpose of our review is to analyze the cases of pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid associated with COVID-19 vaccination and to investigate the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying the new development or flare-up of these diseases in association with vaccination. Our results show that the association between COVID-19 vaccines and AIBDs is a possible event.

1. Introduction

Mucocutaneous adverse events have emerged as some of the most frequently reported reactions associated with COVID-19 vaccination, drawing considerable attention from the medical community. These reactions encompass a broad spectrum of clinical presentations, which can be classified into various categories depending on the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms. These mechanisms include hypersensitivity reactions, notably types I and IV, which involve immediate and delayed immune responses, respectively. Additionally, local site reactions at the injection site, autoimmune-mediated reactions, functional angiopathies, and the reactivation of latent viral conditions have been identified as potential contributors to these adverse skin manifestations following the administration of COVID-19 vaccines [1,2].

Within the broader scope of autoimmune diseases, there has been a notable increase in reports of new onset or recurrence of autoimmune bullous diseases (AIBDs) following COVID-19 vaccination. These diseases, characterized by the formation of blisters on the skin and mucous membranes, are particularly concerning due to their chronic nature and the significant impact they have on patients’ quality of life [3]. Among the various types of AIBD, pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid (BP) are the most prominent, each with distinct pathophysiological features. Pemphigus is characterized by the presence of autoantibodies directed against desmosomes, the structures that facilitate cell-to-cell adhesion within the epidermis, leading to intraepidermal blistering. In contrast, BP involves autoantibodies targeting hemidesmosomes, which anchor the epidermis to the underlying basement membrane, resulting in subepidermal blistering.

Given the increasing number of reported cases, there is a pressing need to understand the potential relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and the onset or exacerbation of these diseases. The aim of our study was to conduct a comprehensive review of the recent literature focusing on cases of new diagnoses and flare-ups of pemphigus and BP following COVID-19 vaccination. By examining these cases, we seek to elucidate any patterns or trends that may contribute to a better understanding of the potential risks associated with COVID-19 vaccines in relation to these serious autoimmune conditions [4].

2. Methods

Comprehensive literature research was conducted on MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, embase, scopus, and Google Scholar databases until May 2024. The following keywords were used to research data: “bullous pemphigoid”, “pemphigus”, “pemphigus vulgaris (PV”), “pemphigus foliaceus (PF)”, “autoimmune bullous disease”, “immune-mediated inflammatory disease”, “COVID-19”, “vaccination”, “vaccine”, “skin manifestations”, “adverse events”, “Pfizer/BioNTech”, “BNT162b2”, “Moderna”, “mRNA-1273”, “AstraZeneca”, “AZD1222”, “Covishield”, “Johnson & Johnson”, “Ad26.COV2.S”, “BBIBP-CorV”, “Sinopharm”, “CoronaVac”, “mRNA”, “viral-vector”, “cutaneous”, “side effect”. Data from the selected case reports and case series were analyzed, and a total of 62 articles were found to be relevant. The references of the selected manuscripts were evaluated to include articles that could have been missed. Our analysis included EMA-approved vaccines, and the main vaccines spread globally.

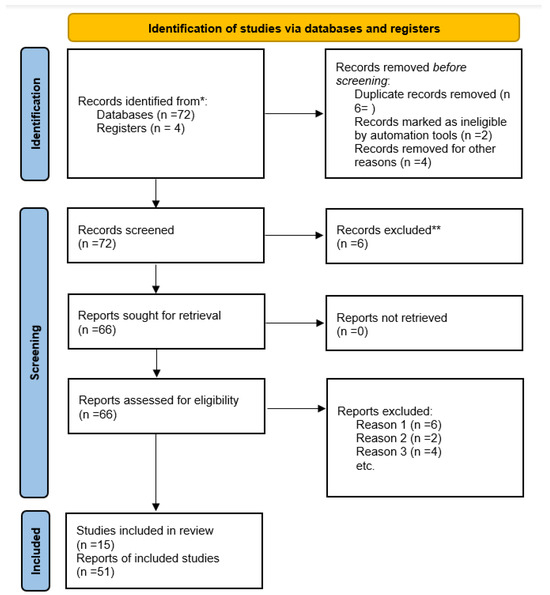

The selection and extraction of relevant data followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews that include searches of databases and registers only. * Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). ** If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [5]. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

2.1. Study Selection

In the first step, two researchers (M.D. and F.M.) reviewed the retrieved articles and removed the duplicates. In other steps, the researchers screened the title and abstract of the records, and the ineligible studies were removed. Then, the authors surveyed the full text of the remaining studies based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the eligible studies were identified.

We decided to exclude certain articles based on the following criteria: articles that were not original research, such as reviews or editorials; articles for which the full text was unavailable; papers that were only available as abstracts, including conference abstracts; clinical trials that were still ongoing and had not yet published results; articles written in languages other than English.

2.2. Risk of Bias Selection

The quality of enrolled studies was appraised by two investigators (F.M. and T.B) using the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for letter to editor, case report, case series, and reviews. Through evaluating the methodology, the overall risk of bias was judged as low, high, or of some concern. If differing opinions existed, the third author (M.M.) was consulted for arbitration.

3. Result

Data resulting from the 62 reviewed manuscripts are synthesized in Table 1. A total of 59 cases of pemphigus and 83 of BP following COVID-19 vaccination were collected, amounting to a total of 142 cases of autoimmune blistering skin diseases (AIBDs). Data on the vaccination dose and the time to onset the symptoms refer to the last dose of vaccine administered before the onset of clinical manifestations.

Table 1.

Pemphigus and BP following COVID-19 vaccination. BP: bullous pemphigoid; PV: pemphigus vulgaris (PV); PF: pemphigus foliaceus.

Data on registered cases of BP are reported in Table 2. A total of 83 cases of pemphigoid were registered, including 78 BP cases, 2 oral mucous membrane pemphigoid cases, 1 case of pemphigoid gestationis, 1 case of anti-p200 BP, and 1 case of dyshidrosiform BP. Among these, 46 cases involved the male population (55.42%). The mean age was 72 ± 12.7, while the average time of onset of symptoms was 11 ± 10.8 days. Most cases occurred following vaccination with BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) [49, (59%)]. The new diagnoses were 43 (51.8%), and pemphigoid cases occurred mainly after the administration of the second dose [38 (45.8%)].

Table 2.

Patient characteristics, clinical manifestations, timing to onset of symptoms, type and dose of COVID-19 vaccination received in patients with pemphigoid after vaccination. BP: bullous pemphigoid.

Data on registered cases of pemphigus are reported in Table 3. A total of 59 cases of pemphigus were registered, including 33 cases of PV, 19 cases of PF, 1 case of pemphigus vegetans, 1 case of pemphigus erythematosus, 1 case of oral pemphigus, 1 case of IgA pemphigus, and 3 cases of an unspecified subtype of pemphigus. The mean age was 55 ± 16.6, while the average time of onset of symptoms was 14 ± 11.7 days from the last vaccination. The female population was involved in a higher percentage [34, (57.6%)]. Most cases developed as a result of vaccinations with BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) [29, (49.2%)] and mainly after the administration of the second dose [24, (40.7%)].

Table 3.

Patient characteristics, clinical manifestations, timing to onset of symptoms, type and dose of COVID-19 vaccination received in patients with pemphigus after vaccination. PV: pemphigus vulgaris (PV); PF: pemphigus foliaceus.

4. Discussion

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune blistering disease involving autoantibodies against BP180 and BP230 proteins in the basement membrane. Triggers include UV radiation, trauma, drugs, malignancies, and vaccinations. Cases have been associated with vaccines for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, polio, pertussis, meningococcal disease, pneumococcal disease, hepatitis B, and rabies. Pemphigus, another autoimmune disorder affecting the skin and mucous membranes, can also be triggered by infections, radiation, drugs, vaccines, pregnancy, or stress, particularly in genetically predisposed individuals. Vaccines such as those for influenza, hepatitis B, rabies, and tetanus have been reported to trigger or exacerbate the disease [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

It is well-established that vaccinations and infections can exacerbate autoimmune diseases, including after COVID-19 vaccines [73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85]. Numerous new-onset autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Guillain-Barré syndrome, autoimmune liver diseases, and rheumatoid arthritis, have been reported post-COVID-19 vaccination. Among autoimmune skin conditions, cases of vitiligo, alopecia areata, lupus, pityriasis rosea, herpes zoster, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and autoimmune blistering diseases (AIBD) have also been noted in a systematic review by Ghanaatpisheh et al. [86].

BP and pemphigus can be triggered by environmental factors stimulating autoimmunity in susceptible individuals. COVID-19 vaccines may contribute through mechanisms such as epitope spreading, molecular mimicry, and bystander activation. A systematic review suggests that molecular mimicry between the spike protein and basement membrane components, like BP230 and BP180, could lead to autoantibody production. Vaccination also strongly activates T-helper lymphocytes, cytokine production, autoantibody generation, and complement pathway activation, causing basement membrane damage.

Pemphigus cases post-vaccination are similarly linked to mechanisms like molecular mimicry and bystander activation, with a potential role for CD8+ lymphocytes and the Fas/FasL pathway [33]. Our findings show an increased number of BP and pemphigus cases following mRNA vaccines, particularly BNT162b2, consistent with other studies [78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87].

There are cases in the literature to report regarding the occurrence or exacerbation of pemphigus following other vaccines. Regarding PV, Cozzani et al. reported a case of pemphigus vulgaris (PV) that developed following tetanus and diphtheria vaccination in an 11-year-old girl. Additionally, Berkun et al. and Mignogna et al. documented two separate instances of PV occurring after vaccination, with one emerging 3 months post-hepatitis B vaccination and the other 1 month after receiving the influenza vaccine [88,89,90].

Other cases are reported as exacerbation of pre-existing PV after influenza vaccination [91].

A different discussion exists for BP because there are no definite and reported data of association in the literature but only reports mostly in pediatric age following the combination of various vaccines. Therefore, with respect to PV, it is not possible to correlate it with one type of vaccine [92,93,94,95].

The mechanisms that cause relapse after vaccination remain uncertain. Two main hypotheses have been proposed: (i) an overactive immune response in individuals with a genetic predisposition, possibly leading to the development of anti-desmoglein antibodies, and (ii) cross-reactivity between vaccine antigens and pemphigus antigens. While there is no definitive evidence supporting these theories in pemphigus or other immune-mediated blistering conditions, such mechanisms have been suggested in the vaccine-induced worsening of other autoimmune diseases [96].

Influenza vaccination is generally recommended for patients on immunosuppressive therapy; however, it may trigger a flare-up of the underlying disease in individuals receiving treatment for autoimmune disorders [96,97,98,99,100].

As reported for COVID-19 vaccination, we can certainly say that although the association may also be present with other vaccines, the benefit of the vaccine itself far outweighs the risk of both occurrence and exacerbation.

5. Conclusions

COVID-19 vaccines were developed to overcome the pandemic period, and the mass administration of such vaccines has led to adverse reactions not often detected in clinical trials. The association between COVID-19 vaccines and AIBD is a possible event. However, the exact correlation between the development of bullous diseases and vaccine administration requires clarification and needs further investigation. The identification of a potential causal relationship between vaccination and the occurrence or recurrence of these diseases is important for assessing the risk and counseling patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M. and T.B.; methodology, M.M.; software, M.N.; validation, M.D., L.P. and C.P.; formal analysis, M.D.; investigation, F.M.; resources, T.B.; data curation, L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P.; writing—review and editing, F.M.; visualization, C.P.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, C.P.; funding acquisition, M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are reported in the current study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Martora, F.; Fabbrocini, G.; Nappa, P.; Megna, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions of patients with rare diseases: An experience of a Southern Italy referral center. Int. J. Dermatol. 2022, 61, e237–e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seirafianpour, F.; Pourriyahi, H.; Gholizadeh Mesgarha, M.; Pour Mohammad, A.; Shaka, Z.; Goodarzi, A. A systematic review on mucocutaneous presentations after COVID-19 vaccination and expert recommendations about vaccination of important immune-mediated dermatologic disorders. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shakoei, S.; Kalantari, Y.; Nasimi, M.; Tootoonchi, N.; Ansari, M.S.; Razavi, Z.; Etesami, I. Cutaneous manifestations following COVID-19 vaccination: A report of 25 cases. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rasner, C.J.; Schultz, B.; Bohjanen, K.; Pearson, D.R. Autoimmune bullous disorder flares following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination: A case series. J. Med. Case Rep. 2023, 17, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffa, M.E.; Maglie, R.; Montefusco, F.; Pipitò, C.; Senatore, S.; Antiga, E. Severe bullous pemphigoid following COVID-19 vaccination resistant to rituximab and successfully treated with dupilumab. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, e135–e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabria, E.; Antonelli, A.; Lavecchia, A.; Giudice, A. Oral mucous membrane pemphigoid after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Oral. Dis. 2024, 30, 782–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yamamoto, S.; Koga, H.; Tsutsumi, M.; Ishii, N.; Nakama, T. Bullous pemphigoid associated with prodromal-phase by repeated COVID-19 vaccinations. J. Dermatol. 2024, 51, e6–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Brazão, C.; Mancha, D.; Soares-de-Almeida, L.; Filipe, P. Reply to: ‘Severe bullous pemphigoid following COVID-19 vaccination resistant to rituximab and successfully treated with dupilumab’ by Baffa et al. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, e578–e580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Antonia, M.; Anedda, S.; Usai, F.; Atzori, L.; Ferreli, C. Bullous pemphigoid triggered by COVID-19 vaccine: Rapid resolution with corticosteroid therapy. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martora, F.; Ruggiero, A.; Battista, T.; Fabbrocini, G.; Megna, M. Bullous pemphigoid and COVID-19 vaccination: Management and treatment reply to ‘Bullous pemphigoid in a young male after COVID-19 mRNA vaccine: A report and brief literature review’ by Pauluzzi et al. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, e35–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Corrá, A.; Barei, F.; Genovese, G.; Zussino, M.; Spigariolo, C.B.; Mariotti, E.B.; Quintarelli, L.; Verdelli, A.; Caproni, M.; Marzano, A.V. Five cases of new-onset pemphigus following vaccinations against coronavirus disease 2019. J. Dermatol. 2023, 50, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cowan, T.L.; Huang, C.; Murrell, D.F. Autoimmune blistering skin diseases triggered by COVID-19 vaccinations: An Australian case series. Front. Med. 2023, 9, 1117176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Diab, R.; Rakhshan, A.; Salarinejad, S.; Pourani, M.R.; Ansar, P.; Abdollahimajd, F. Clinicopathological characteristics of cutaneous complications following COVID-19 vaccination: A case series. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maronese, C.A.; Caproni, M.; Moltrasio, C.; Genovese, G.; Vezzoli, P.; Sena, P.; Previtali, G.; Cozzani, E.; Gasparini, G.; Parodi, A.; et al. Bullous Pemphigoid Associated With COVID-19 Vaccines: An Italian Multicentre Study. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 841506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rouatbi, J.; Aounallah, A.; Lahouel, M.; Sriha, B.; Belajouza, C.; Denguezli, M. Two cases with new onset of pemphigus foliaceus after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Young, J.; Mercieca, L.; Ceci, M.; Pisani, D.; Betts, A.; Boffa, M.J. A case of bullous pemphigoid after the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e13–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bailly-Caillé, B.; Jouen, F.; Dompmartin, A.; Morice, C. A case report of anti-P200 pemphigoid following COVID-19 vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. 2022, 23, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Knechtl, G.V.; Seyed Jafari, S.M.; Berger, T.; Rammlmair, A.; Feldmeyer, L.; Borradori, L. Development of pemphigus vulgaris following mRNA SARS-CoV-19 BNT162b2 vaccination in an 89-year-old patient. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e251–e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauluzzi, M.; Stinco, G.; Errichetti, E. Bullous pemphigoid in a young male after COVID-19 mRNA vaccine: A report and brief literature review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e257–e259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avallone, G.; Giordano, S.; Astrua, C.; Merli, M.; Senetta, R.; Conforti, C.; Ribero, S.; Marzano, A.V.; Quaglino, P. Reply to ‘The first dose of COVID-19 vaccine may trigger pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid flares: Is the second dose therefore contraindicated?’ by Damiani G et al. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e433–e435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damiani, G.; Pacifico, A.; Pelloni, F.; Iorizzo, M. The first dose of COVID-19 vaccine may trigger pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid flares: Is the second dose therefore contraindicated? J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, e645–e647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hung, W.K.; Chi, C.C. Incident bullous pemphigoid in a psoriatic patient following mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e407–e409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligrone, L.; Lembo, S.; Cillo, F.; Spennato, S.; Fabbrocini, G.; Raimondo, A. A severe relapse of pemphigus vulgaris after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, e1369–e1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lua, A.C.Y.; Ong, F.L.L.; Choo, K.J.L.; Yeo, Y.W.; Oh, C.C. An unusual presentation of pemphigus foliaceus following COVID-19 vaccination. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2022, 63, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hali, F., Sr.; Araqi, L., Jr.; Marnissi, F.; Meftah, A.; Chiheb, S. Autoimmune Bullous Dermatosis Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Series of Five Cases. Cureus 2022, 14, e23127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hinterseher, J.; Hertl, M.; Didona, D. Autoimmune skin disorders and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination—A meta-analysis. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2023, 21, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, V.; Blum, R.; Möhrenschlager, M. Biphasic bullous pemphigoid starting after first dose and boosted by second dose of mRNA-1273 vaccine in an 84-year-old female with polymorbidity and polypharmacy. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e88–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-López, I.; Moyano-Bueno, D.; Ruiz-Villaverde, R. Bullous pemphigoid and COVID-19 vaccine. Med. Clin. 2021, 157, e333–e334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alshammari, F.; Abuzied, Y.; Korairi, A.; Alajlan, M.; Alzomia, M.; AlSheef, M. Bullous pemphigoid after second dose of mRNA-(Pfizer-BioNTech) COVID-19 vaccine: A case report. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 75, 103420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Desai, A.D.; Shah, R.; Haroon, A.; Wassef, C. Bullous Pemphigoid Following the Moderna mRNA-1273 Vaccine. Cureus 2022, 14, e24126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Agharbi, F.Z.; Eljazouly, M.; Basri, G.; Faik, M.; Benkirane, A.; Albouzidi, A.; Chiheb, S. Bullous pemphigoid induced by the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 149, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aryanian, Z.; Balighi, K.; Azizpour, A.; Kamyab Hesari, K.; Hatami, P. Coexistence of Pemphigus Vulgaris and Lichen Planus following COVID-19 Vaccination. Case Rep. Dermatol. Med. 2022, 2022, 2324212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hatami, P.; Balighi, K.; Nicknam Asl, H.; Aryanian, Z. COVID vaccination in patients under treatment with rituximab: A presentation of two cases from Iran and a review of the current knowledge with a specific focus on pemphigus. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pham, N.N.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Vu, T.T.P.; Nguyen, H.T. Pemphigus Foliaceus after COVID-19 Vaccination: A Report of Two Cases. Case Rep. Dermatol. Med. 2023, 2023, 1218388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bostan, E.; Yel, B.; Akdogan, N.; Gokoz, O. New-onset bullous pemphigoid after inactivated COVID-19 vaccine: Synergistic effect of the COVID-19 vaccine and vildagliptin. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maronese, C.A.; Di Zenzo, G.; Genovese, G.; Barei, F.; Monestier, A.; Pira, A.; Moltrasio, C.; Marzano, A.V. Reply to “New-onset bullous pemphigoid after inactivated COVID-19 vaccine: Synergistic effect of the COVID-19 vaccine and vildagliptin”. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Solimani, F.; Mansour, Y.; Didona, D.; Dilling, A.; Ghoreschi, K.; Meier, K. Development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BNT162b2. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, e649–e651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Singh, A.; Bharadwaj, S.J.; Chirayath, A.G.; Ganguly, S. Development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination and review of literature. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 2311–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutlas, I.G.; Camara, R.; Argyris, P.P.; Davis, M.D.P.; Miller, D.D. Development of pemphigus vulgaris after the second dose of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Oral. Dis. 2021, 28, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongprasom, K.; Pengpis, N.; Phattarataratip, E.; Samaranayake, L. Oral pemphigus after COVID-19 vaccination. Oral. Dis. 2021, 28, 2597–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanshal, M. Dyshidrosiform Bullous Pemphigoid Triggered by COVID-19 Vaccination. Cureus 2022, 14, e26383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alami, S.; Benzekri, L.; Senouci, K.; Meziane, M. Pemphigus foliaceus triggered after inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: Coincidence or causal link? Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lansang, R.P.; Amdemichael, E.; Sajic, D. IgA pemphigus following COVID-19 vaccination: A case report. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2023, 11, 2050313X231181022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wan, V.; Chen, D.; Shiau, C.J.; Jung, G.W. Association between COVID-19 vaccination and bullous pemphigoid—A case series and literature review. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2022, 10, 2050313X221131868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afacan, E.; Edek, Y.C.; İlter, N.; Gülekon, A. Can COVID-19 vaccines cause or exacerbate bullous pemphigoid? A report of seven cases from one center. Int. J. Dermatol. 2022, 61, 626–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, C.; Terada, N.; Harada, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Niiyama, S.; Fukuda, H. Intractable pemphigus foliaceus after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. J. Dermatol. 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rungraungrayabkul, D.; Rattanasiriphan, N.; Juengsomjit, R. Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid Following the Administration of COVID-19 Vaccine. Head Neck Pathol. 2023, 17, 587–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourani, M.; Bidari-Zerehpoosh, F.; Ayatollahi, A.; Robati, R.M. New onset of pemphigus foliaceus following BBIBP COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yıldırıcı, Ş.; Yaylı, S.; Demirkesen, C.; Vural, S. New onset of pemphigus foliaceus following BNT162b2 vaccine. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bardazzi, F.; Carpanese, M.A.; Abbenante, D.; Filippi, F.; Sacchelli, L.; Loi, C. New-onset bullous pemphigoid and flare of pre-existing bullous pemphigoid after the third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mustin, D.E.; Huffaker, T.B.; Feldman, R.J. New-Onset Pemphigoid Gestationis Following COVID-19 Vaccination. Cutis 2023, 111, E2–E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, H.; Young, P.A.; So, J.Y.; Pol-Rodriguez, M.; Rieger, K.E.; Lewis, M.A.; Winge, M.C.G.; Bae, G.H. New-onset pemphigus vegetans and pemphigus foliaceus after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: A report of 2 cases. JAAD Case Rep. 2022, 27, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zou, H.; Daveluy, S. Pemphigus vulgaris after COVID-19 infection and vaccination. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 87, 709–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reis, J.; Nogueira, M.; Figueiras, O.; Coelho, A.; Cunha Velho, G.; Raposo, I. Pemphigus foliaceous after mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2022, 32, 428–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akoglu, G. Pemphigus vulgaris after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: A case with new-onset and two cases with severe aggravation. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalayli, N.; Omar, A.; Kudsi, M. Pemphigus vulgaris after the second dose of COVID-19 vaccination: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2023, 17, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norimatsu, Y.; Yoshizaki, A.; Yamada, T.; Akiyama, Y.; Toyama, S.; Sato, S. Pemphigus vulgaris with advanced hypopharyngeal and gastric cancer following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J. Dermatol. 2023, 50, e74–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Almasi-Nasrabadi, M.; Ayyalaraju, R.S.; Sharma, A.; Elsheikh, S.; Ayob, S. New onset pemphigus foliaceus following AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Falcinelli, F.; Lamberti, A.; Cota, C.; Rubegni, P.; Cinotti, E. Reply to ‘development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BNT162b2′ by Solimani F et al. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e976–e978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ong, S.K.; Darji, K.; Chaudhry, S.B. Severe flare of pemphigus vulgaris after first dose of COVID-19 vaccine. JAAD Case Rep. 2022, 22, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Saffarian, Z.; Samii, R.; Ghanadan, A.; Vahidnezhad, H. De novo severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BBIBP-CorV. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gambichler, T.; Hamdani, N.; Budde, H.; Sieme, M.; Skrygan, M.; Scholl, L.; Dickel, H.; Behle, B.; Ganjuur, N.; Scheel, C.; et al. Bullous pemphigoid after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: Spike-protein-directed immunofluorescence confocal microscopy and T-cell-receptor studies. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 186, 728–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Agharbi, F.Z.; Basri, G.; Chiheb, S. Pemphigus vulgaris following second dose of mRNA-(Pfizer-BioNTech) COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Walmsley, N.; Hampton, P. Bullous pemphigoid triggered by swine flu vaccination: Case report and review of vaccine triggered pemphigoid. J. Dermatol. Case Rep. 2011, 5, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Potestio, L.; Genco, L.; Villani, A.; Marasca, C.; Fabbrocini, G.; Fornaro, L.; Ruggiero, A.; Martora, F. Reply to ‘Cutaneous adverse effects of the available COVID-19 vaccines in India: A questionnaire-based study’ by Bawane J et al. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2022, 36, e863–e864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkun, Y.; Mimouni, D.; Shoenfeld, Y. Pemphigus following hepatitis B vaccination coincidence or causality? Autoimmunity 2005, 38, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykal, C.; Okan, G.; Sarica, R. Childhood bullous pemphigoid developed after the first vaccination. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2001, 44 Pt 2, 348–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, B.; Descamps, V.; Bouscarat, F.; Crickx, B.; Belaich, S. Bullous pemphigoid induced by vaccination. Br. J. Dermatol. 1996, 135, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, A.; Nayak, S.U.K.; Shenoi, S.D.; Rao, R.; Monappa, V. Bullous pemphigoid triggered by rabies vaccine. Indian. J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2020, 86, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lear, J.T.; Tan, B.B.; English, J.S.C. Bullous Pemphigoid Following Influenza Vaccination. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1996, 21, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdivielso-Ramos, M.; Velázquez, D.; Tortoledo, A.; Hernanz, J.M. Penfigoide ampolloso infantil en relación con la vacunación hexavalente, meningococo y pneumococo. An. Pediatr. 2011, 75, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, F.; Sinagra, J.L.M.; Salemme, A.; Fania, L.; Mariotti, F.; Pira, A.; Didona, B.; Di Zenzo, G. Pemphigus: Trigger and predisposing factors. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1326359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guimarães, L.E.; Baker, B.; Perricone, C.; Shoenfeld, Y. Vaccines, adjuvants and autoimmunity. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 100, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, P.; Li, X.M.; Shuai, Z.W.; Ye, D.Q.; Pan, H.F. New-onset autoimmune phenomena post-COVID-19 vaccination. Immunology 2022, 165, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genco, L.; Cantelli, M.; Noto, M.; Battista, T.; Patrì, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Vastarella, M. Alopecia Areata after COVID-19 Vaccines. Skin. Appendage Disord. 2023, 9, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kasmikha, L.C.; Mansour, M.; Goodenow, S.; Kessler, S.; Appel, J. Vitiligo Following COVID-19 Vaccination and Primary Infection: A Case Report and Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e45546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pathak, G.N.; Pathak, A.N.; Rao, B. The role of COVID-19 vaccines in the development and recurrence of pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martora, F.; Villani, A.; Battista, T.; Fabbrocini, G.; Potestio, L. COVID-19 vaccination and inflammatory skin diseases. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, V.; Fabbrocini, G.; Martora, L.; Martora, F. A Case of New-Onset Lichen Planus after COVID-19 Vaccination. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 801–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martora, F.; Fabbrocini, G.; Marasca, C. Pityriasis rosea after Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccine: A case series. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martora, F.; Villani, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Battista, T. COVID-19 and cutaneous manifestations: A review of the published literature. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martora, F.; Picone, V.; Fornaro, L.; Fabbrocini, G.; Marasca, C. Can COVID-19 cause atypical forms of pityriasis rosea refractory to conventional therapies? J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1292–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martora, F.; Fabbrocini, G.; Nappa, P.; Megna, M. Reply to ‘Development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BNT162b2′ by Solimani et al. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2022, 36, e750–e751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Liang, X.; Zhang, J.; Su, H.; Chen, Y. Pemphigus during the COVID-19 Epidemic: Infection Risk, Vaccine Responses and Management Strategies. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghanaatpisheh, A.; Safari, M.; Haghshenas, H.; Motamed-Sanaye, A.; Atefi, A.H.; Kamangarpour, K.; Bagherzadeh, M.A.; Kamran-Jahromi, A.; Darayesh, M.; Kouhro, N.; et al. New-onset or flare-up of bullous pemphigoid associated with COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review of case report and case series studies. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1293920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vastarella, M.; Picone, V.; Martora, F.; Fabbrocini, G. Herpes zoster after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine: A case series. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2021, 35, e845–e846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzani, E.; Cacciapuoti, M.; Parodi, A.; Rebora, A. Pemphigus following tetanus and diphtheria vaccination. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002, 147, 188–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martora, F.; Battista, T.; Marasca, C.; Genco, L.; Fabbrocini, G.; Potestio, L. Cutaneous Reactions Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Review of the Current Literature. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 2369–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignogna, M.; Lo Muzio, L. Pemphigus induction by influenza vaccination. Int. J. Dermatol. 2000, 39, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, C.; Caldarola, G.; D’agostino, M.; Zampetti, A.; Amerio, P.; Feliciani, C. Exacerbation of pemphigus after influenza vaccination. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2008, 33, 718–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baroero, L.; Coppo, P.; Bertolino, L.; Maccario, S.; Savino, F. Three case reports of post immunization and post viral Bullous Pemphigoid: Looking for the right trigger. BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potestio, L.; Villani, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Martora, F. Cutaneous reactions following booster dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccination: What we should know? J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 5339–5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Fuente, S.; Hernández-Martín, Á.; de Lucas, R.; González-Enseñat, M.A.; Vicente, A.; Colmenero, I.; González-Beato, M.; Suñol, M.; Torrelo, A. Postvaccination bullous pemphigoid in infancy: Report of three new cases and literature review. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2013, 30, 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, L.; Pedicelli, C.; Fania, L.; De Luca, N.; Condorelli, A.G.; Mazzanti, C.; Di Zenzo, G. Infantile bullous pemphigoid following vaccination. Eur. J. Dermatol. EJD 2018, 28, 708–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoenfeld, Y.; Aron-Maor, A. Vaccination and autoimmunity-‘vaccinosis’: A dangerous liaison? J. Autoimmun. 2000, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, E. Vaccination and autoimmune diseases: The argument against. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. IMAJ 2004, 6, 433–435. [Google Scholar]

- Salemi, S.; D’Amelio, R. Could autoimmunity be induced by vaccination? Int. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 29, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, T.; Descotes, J. Autoimmune diseases and vaccinations. Eur. J. Dermatol. EJD 2004, 14, 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Martora, F.; Marasca, C.; Battista, T.; Fabbrocini, G.; Ruggiero, A. Management of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa during COVID-19 vaccination: An experience from southern Italy. Comment on: ‘Evaluating the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa’. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 2026–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).