Abstract

Solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients are at greater risk of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and have attenuated response to vaccinations. In the present meta-analysis, we aimed to evaluate the serologic response to the COVID-19 vaccine in SOT recipients. A search of electronic databases was conducted to identify SOT studies that reported the serologic response to COVID-19 vaccination. We analyzed 44 observational studies including 6158 SOT recipients. Most studies were on mRNA vaccination (mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2). After a single and two doses of vaccine, serologic response rates were 8.6% (95% CI 6.8–11.0) and 34.2% (95% CI 30.1–38.7), respectively. Compared to controls, response rates were lower after a single and two doses of vaccine (OR 0.0049 [95% CI 0.0021–0.012] and 0.0057 [95% CI 0.0030–0.011], respectively). A third dose improved the rate to 65.6% (95% CI 60.4–70.2), but in a subset of patients who had not achieved a response after two doses, it remained low at 35.7% (95% CI 21.2–53.3). In summary, only a small proportion of SOT recipients achieved serologic response to the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, and that even the third dose had an insufficient response. Alternative strategies for prophylaxis in SOT patients need to be developed. Key Contribution: In this meta-analysis that included 6158 solid organ transplant recipients, the serologic response to the COVID-19 vaccine was extremely low after one (8.6%) and two doses (34.2%). The third dose of the vaccine improved the rate only to 66%, and in the subset of patients who had not achieved a response after two doses, it remained low at 36%. The results of our study suggest that a significant proportion of solid organ transplant recipients are unable to achieve a sufficient serologic response after completing not only the two series of vaccination but also the third booster dose. There is an urgent need to develop strategies for prophylaxis including modified vaccine schedules or the use of monoclonal antibodies in this vulnerable patient population.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has led to a global health emergency [1]. It has been reported that older individuals, patients with pre-existing comorbidities, and those that are immunosuppressed are at greater risk of COVID-19 and experiencing severe pneumonia [2,3,4]. Patients who have undergone organ transplants require lifelong immunosuppressive therapy. Long-term maintenance immunosuppression including the combinatory use of calcineurin inhibitors, antimetabolites, glucocorticoids (GCs), monoclonal antibodies, and inhibitors of T cell activation remains the mainstay in improving graft survival in transplant recipients [5,6]. In the United States, 39,000 organ transplants were performed in 2020 [7]. Renal transplants were the most commonly performed, followed by liver, heart, and lung transplantation [7]. Furthermore, more than 100,000 patients are on the national transplant waiting lists. Patients with solid organ transplants (SOT) are at risk for various infections because the immunosuppressive agents dramatically reduce immunity against viruses, bacteria, and other pathogens [8,9]. During periods of a pandemic, the protection of the safety or health of SOT patients is an important priority [10].

Salto-Alejandre et al., demonstrated that old age and a shorter interval between transplant and COVID-19 diagnosis showed an association with poor COVID-19 outcomes in SOT patients with a case fatality rate greater than 20% [4]. These reports suggest that there is a need for effective prophylaxis in SOT recipients. Due to the lack of efficacious therapies for COVID-19, vaccinations that could prevent infections are of importance in lowering the mortality risk [11]. COVID-19 vaccines were developed and a large number of studies demonstrated that mRNA COVID-19 vaccinations are efficacious and safe [12]. Patients who were on immunosuppressive drugs were excluded from initial vaccination trials, so the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccinations in transplant recipients remains unclear [13]. Guideline recommendations are that transplant recipients should receive COVID-19 vaccination unless there is any contraindication. Studies of other infectious conditions have shown that SOT recipients have diminished humoral response to vaccinations [14]. Boyarsky et al., showed that kidney or liver transplant patients had decreased immunogenicity to mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 vaccinations [15]. Most studies assessing the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccinations in transplant recipients are of limited sample size [16,17].

In order to improve clinical care and protect this vulnerable patient population, it is important to understand the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccinations in transplant recipients. We aimed to integrate data from various studies to evaluate the serologic response to COVID-19 vaccines in SOT patients.

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy of Selecting Studies

We conducted the present meta-analysis according to a protocol that is in accordance with the PRISMA guideline [18]. We have submitted the protocol to the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (pending approval) [19]. PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, and medRxiv were electronically searched on 1 August 2021.

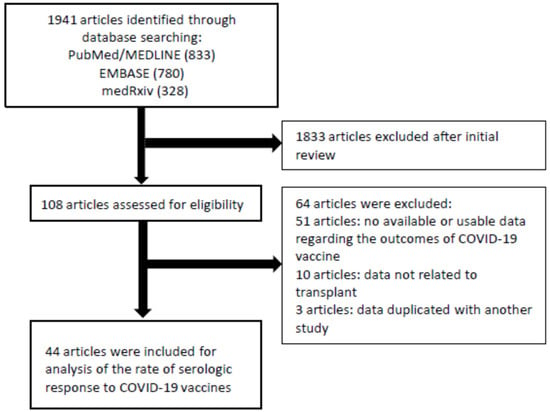

Observational studies that reported the serologic response to COVID-19 vaccines in SOT recipients were included. No restrictions for country, language, age, or type of vaccine of the study were imposed. Two members (AS and AL) screened each potential study in an independent manner to assess the eligibility. When any issues or disagreements were found, they were resolved after discussion. We used the following terms to search for eligible studies: “SARS-CoV-2”, “COVID-19”, “vaccine”, “transplant”, “transplantation”, “liver”, “kidney”, “heart”, “lung”, “pancreas”, “multi-organ”, and “immunosuppressed”. We also searched bibliographies of eligible articles for any potential references. Manuscripts that were published in non-English language were translated if necessary. We excluded single case reports and studies that only reported adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccines. We contacted the corresponding author of studies to obtain missing data when necessary. Figure 1 shows the search strategy.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the assessment of the studies identified in the meta-analysis.

2.2. Extraction of Data and Assessment of Quality

The data of each eligible study were independently extracted in duplicate by the authors (AS and AL). Extracted data included study characteristics such as name of authors, publication year, country, administered vaccine, duration, sample size, transplanted organ, treatment, characteristics of patients, and results of serologic tests. The diseases were categorized into the following groups according to the transplanted organ: (1) kidney, (2) heart/lung, and (3) liver. Studies that reported outcomes in various organ transplant recipients without distinction were classified as (4) mixed.

The risk of bias of the studies was assessed by the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist [20,21]. The quality of evidence obtained from the present meta-analysis was rated by the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [22].

2.3. Assessment of Outcomes

Serologic response rate to COVID-19 vaccine was the primary outcome of the present meta-analysis. We separately assessed the rate of response following the first, second, and third vaccination. The rate of serologic response in transplant recipients compared to control population was the secondary outcome. The number of patients achieving antibody levels above the cut-off of the test method used in each study divided by the total number of patients was defined as the rate of serologic response [23]. A majority of studies used one of the three commercially available antibody tests (Roche, DiaSorin, and Abbott), so applying a common cut-off value between studies was not possible; however, they all have excellent sensitivity (98–100%) [21,24]. When response was tested at different timing, the time point closest to 4 weeks following the vaccine was chosen [21].

Meta-regression and subgroup analyses based on transplanted organs (kidney, heart/lung, liver, mixed group), patient’s age, and proportion of patients on immunosuppressive medications were performed. Immunosuppressive medications such as calcineurin inhibitors, mycophenolate, antimetabolites, monoclonal antibodies, and inhibitors of T cell activation were included, but were not assessed separately because a majority of studies did not report outcomes separately according to treatment.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A meta-analysis of the serologic response rate to COVID-19 vaccine was undertaken by random effects model [21]. Heterogeneity across included studies was analyzed by I2 statistic. Heterogeneity was defined as low, moderate, and high when I2 value was <25%, 25–75%, and >75%, respectively [25]. Heterogeneity was also evaluated by Cochran’s Q-statistics (p < 0.10) [26]. Publication bias was analyzed with Begg’s and Egger’s tests. When more than 3 studies were included in the meta-analysis, funnel plots were created to assess asymmetry [27,28]. Subgroup analyses and random effects meta-regression models were used to evaluate the contribution of each risk factor to the response to vaccination [21]. When performing multivariate meta-regression, all variables included in the univariate meta-regression were included as they were all considered clinically important.

Preprint studies were included because they are a substantial part of the available COVID-19 literature [23]. However, we conducted sensitivity analyses by excluding preprint studies because they still lack peer-review [29]. One study included exclusively a non-mRNA vaccine (Ad26.COV2.S), so it was analyzed separately. One study removed analyses that were undertaken to assess whether the results of the meta-analyses were biased by a single study [21].

We used Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software (version 3; Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA) for all statistical analyses. We used a two-sided p-value of 0.05 for significance except for Q-statistics.

2.5. Data Sharing and Access

Data of the present study will be made available when requested from the corresponding author. All coauthors of the present study had access to the data of the study and approved final version of the manuscript.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

As shown in Figure 1, 1941 studies were identified through the literature search. We excluded 1833 studies after screening of title and abstract. We assessed 108 studies for eligibility and found 44 studies (6158 patients) that met the eligibility criteria. Twenty-two studies included only patients with kidney transplant, seven included patients with heart and/or lung transplant, and one included patients with liver transplant (Table 1). Fourteen studies included patients with various SOTs (mixed group), which included kidney, heart/lung, liver, and pancreas, but did not report outcomes separately. Twenty-six and five studies included patients vaccinated with only BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273, respectively. Eight studies included patients vaccinated with either BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273. One study only used AD26.COV2.S. One study used ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 as a third dose in patients who previously received two series of BNT162b2. Another study used AD26.COV2.S in patients who previously received two series of BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273.

Table 1.

Characteristics and outcomes of the included studies.

Twenty-one and thirty-five studies were eligible for evaluation of serologic response after one and two doses, respectively. Four and fifteen studies compared serologic response after one or two doses of COVID-19 vaccination to controls with no history of transplant. Twelve studies reported outcomes in patients who received a third vaccine dose [16,17,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Most studies measured outcomes 3–5 weeks following the vaccine (Table 1). The summary of characteristics of the studies that were included in the meta-analysis is shown in Table 1. We evaluated the risk of bias in the studies with the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist (Supplementary Table S1). Most of the studies were of medium–high quality.

3.2. Serologic Response following a Single Dose of COVID-19 Vaccination

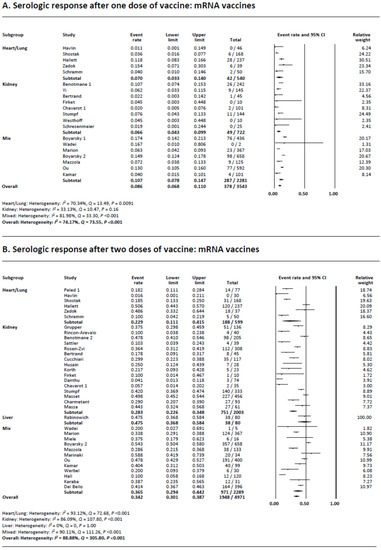

There were 21 studies that evaluated the serologic response following the first vaccination in transplant recipients (20 mRNA vaccine and one AD26.COV2.S vaccine). The serologic response following a single dose of mRNA vaccine was extremely low at 8.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 6.8–11.0) (Figure 2A). Subgroup analysis demonstrated that the rates were 7.0% (95% CI 3.3–14.0), 6.6% (95% CI 4.3–9.9), and 10.7% (95% CI 7.8–14.7) in heart or lung transplant recipients, kidney transplant recipients, and mixed transplant recipients, respectively. The one study that reported a serologic response following a single dose of AD26.COV2.S vaccination showed a rate of 16.7% (Supplementary Figure S1A).

Figure 2.

(A) Meta-analysis of serological response after one dose of vaccine: mRNA vaccines. (B) Meta-analysis of serological response after two doses of vaccine: mRNA vaccines.

Heterogeneity was present (I2 = 74.2%) in the meta-analysis of mRNA vaccines possibly due to the differences in sample size and reported rates of the studies. Multivariate meta-regression showed that the proportion of patients on GCs (regression coefficient −0.029, 95% CI −0.052–0.0061, p = 0.013) was a source of heterogeneity. Studies that used both types of mRNA vaccines showed a greater response rate compared to studies that only included BNT162b2 vaccine (coefficient 1.08, 95% CI 0.20–1.96), p = 0.016) (Supplementary Table S2).

Visual evaluation of the funnel plot of the mRNA vaccine studies showed no asymmetry; however, we found publication bias with Egger’s test (p < 0.001), but not with Begg’s test (p = 0.36) (Supplementary Figure S2A).

We performed sensitivity analyses to evaluate whether any single study influenced the outcomes (Supplementary Figure S2B). The results were unchanged when each study was removed one at a time from the meta-analyses. Specifically, the removal of the one preprint study showed similar results [37]. Subgroup analysis stratifying based on the type of the vaccination demonstrated that the serologic response rates were 5.4%, 11.8%, and 10.7% in studies that used BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, or both types of vaccines, respectively (Supplementary Figure S2C).

3.3. Serologic Response following Two Doses of COVID-19 Vaccination

Thirty-five studies were available for the assessment of the serologic response following two doses of mRNA vaccination. There were no studies that used non-mRNA vaccines. The pooled serologic response rate was 34.2% (95% CI 30.1–38.7) (Figure 2B). Subgroup analysis demonstrated that the rates were 22.9% (95% CI 11.1–45.9), 28.3% (95% CI 22.6–34.8), and 35.5% (95% CI 29.4–44.2) in heart/lung transplant recipients, kidney transplant recipients, and mixed transplant group, respectively. The one liver transplant study reported a rate of 47.5%.

Heterogeneity was present (I2 = 88.9%) which was possibly due to the differences in the sample size and the response rates of the included studies. Multivariate meta-regression demonstrated that older age (regression coefficient −0.10, 95% CI −0.19–0.020), p = 0.016) and GC use (regression coefficient −0.014, 95% CI −0.025–0.0024), p = 0.017) were significant sources of heterogeneity. (Supplementary Table S3).

Visual evaluation of the funnel plot showed no asymmetry; however, we found publication bias with Egger’s and Begg’s tests (p < 0.001 and p = 0.0038, respectively) (Supplementary Figure S3A).

We performed sensitivity analyses to evaluate whether any single study influenced the outcomes (Supplementary Figure S3B). The results were unchanged when each study was removed one at a time from the meta-analyses. Removal of the three preprint studies showed similar results (Supplementary Figure S3C). Subgroup analysis stratifying based on the type of vaccine showed that the rates were 28.9%, 26.6%, and 40.6% in studies that used BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, or both types of vaccines, respectively (Supplementary Figure S3D).

A few studies that reported antibody titers or concentrations showed greater than ten-fold lower values in transplant recipients (Table 1).

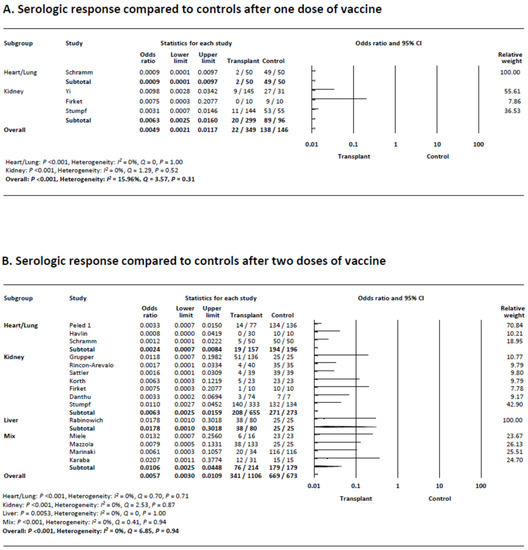

3.4. Serologic Response following a Single Dose of COVID-19 Vaccination Compared to Controls

There were four studies that included control patients after one dose of the vaccine. Meta-analysis demonstrated that transplant recipients were less likely to achieve a serologic response compared to controls (6.3% 94.5%; odds ratio [OR] 0.0049, 95% CI 0.0021–0.012, p < 0.001) (Figure 3A). Subgroup analysis demonstrated that both heart and/or lung and kidney transplant recipients achieved statistically significantly lower rates of response compared to control patients (4.0% vs. 98.0%; OR 0.0009, 95% CI 0.0001–0.0097, p < 0.001 and 6.7% vs. 92.8%; OR 0.0049, 95% CI 0.0021–0.012, p < 0.001, respectively).

Figure 3.

(A) Meta-analysis of serological response compared to controls after one dose of vaccine. (B) Meta-analysis of serological response compared to controls after two doses of vaccine.

Heterogeneity was absent (I2 = 16.0%). Visual evaluation of the funnel plot showed no asymmetry, and no publication bias was found (Begg’s p = 0.73, Egger’s p = 0.51) (Supplementary Figure S4A).

3.5. Serologic Response following Two Doses of COVID-19 Vaccination Compared to Controls

There were 15 studies that included control patients after two doses of vaccine. Meta-analysis demonstrated that transplant recipients were less likely to achieve a serologic response compared to controls (30.8% vs. 99.4%; OR 0.0057 (95% CI 0.0030–0.011), p < 0.001) (Figure 3B). Subgroup analysis demonstrated that heart and/or lung and kidney transplant recipients as well as the mixed transplant group achieved statistically significantly lower response rates compared to controls (12.1% vs. 99.0%; OR 0.0024 [95% CI 0.0007–0.0084], 31.8% vs. 99.3%; OR 0.0063 [95% CI 0.0025–0.016], 35.5% vs. 100%; OR 0.011 [95% CI 0.0025–0.045], respectively, and all p < 0.001).

There was no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). Visual evaluation of the funnel plot showed no asymmetry, and no publication bias was found with Begg’s and Egger’s tests (p = 0.20, p = 0.47) (Supplementary Figure S4B).

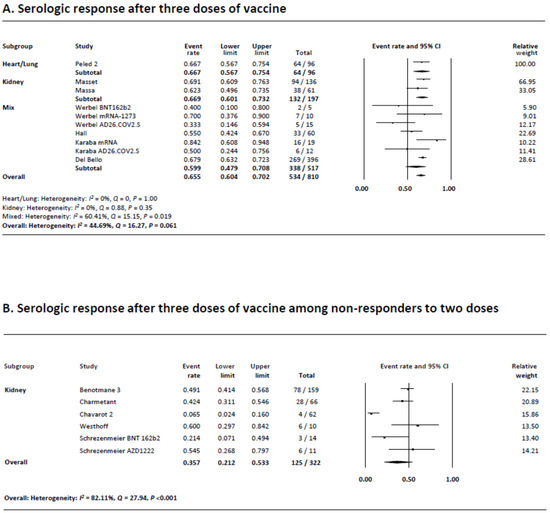

3.6. Serologic Response following Three Doses of COVID-19 Vaccination

Ten studies reported the serologic response following a third dose of COVID-19 vaccination. Five studies used the same mRNA vaccine for all three doses (BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273) whereas three studies used a different mRNA vaccine for the third dose. Two studies used mRNA vaccines as the first two series followed by Ad26.COV2.S as the third dose. As can be seen in Figure 4A, the rate of serologic response was 65.5% (95% CI 60.4–70.2), which was nearly two-fold greater than the rate after two doses. Subgroup analysis demonstrated that the rates were 66.7% (95% CI 56.7–75.4), 66.9% (95% CI 60.1–73.2), and 59.9% (95% CI 47.9–70.8) in heart and/or lung transplant recipients, kidney transplant recipients, and mixed group, respectively. The rate was lower with Ad26.COV2.S as the third dose compared to using the same or different combination of mRNA vaccines (41.0% (95% CI 24.2–60.2%) vs. 66.1% (95% CI 62–69.9%)–70.1% (95% CI 43.7–87.6%), respectively) (Supplementary Figure S5B). The results were unchanged when each study was removed one at a time from the meta-analyses (Supplementary Figure S5C).

Figure 4.

(A) Meta-analysis of serological response after three doses of vaccine. (B) Meta-analysis of serological response after three doses of vaccine among non-responders to two doses.

Heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 44.7%) possibly due to the differences in the sample size and reported rates of the studies. Visual evaluation of the funnel plot showed no asymmetry, and no publication bias was found with Begg’s and Egger’s tests (p = 0.37, p = 0.19) (Supplementary Figure S5A).

3.7. Serologic Response following Three Doses of COVID-19 Vaccination in Non-Responders after Two Doses

There were six studies that reported the serologic response after a third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients who did not show a response following two vaccination. All studies only included kidney transplant recipients. Four studies used the same mRNA vaccine for all three doses (BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273) whereas one study each used BNT162b2 as the first two series followed by AZD1222 or mRNA-1273 as the third dose. As can be seen in Figure 4B, the serologic response rate was 35.7% (95% CI 21.2–53.3), which was half of that seen among studies not restricted to two-dose non-responders (Figure 4A). Subgroup analysis demonstrated that the serologic response rates were 54.5% (95% CI 26.8–79.7) and 60.0% (95% CI 29.7–84.2) when AZD122 or mRNA-1273 were administered as the third dose following two doses of BNT162b2, but 27.9% (95% CI 13.3–49.4) when the same mRNA vaccines were used for all three doses (Supplementary Figure S6B). It should be noted that the number of studies that used a different type of the third vaccine was one each. The results were unchanged when each study was removed one at a time from the meta-analyses (Supplementary Figure S6C).

Heterogeneity was present (I2 = 82.1%) possibly due to the differences in the sample size and reported rates of the studies. Visual evaluation of the funnel plot showed no asymmetry, and no publication bias was found with Begg’s and Egger’s tests (p = 0.71, p = 0.36) (Supplementary Figure S6A).

3.8. Quality of Evidence Assessed by GRADE

The quality of evidence of this analysis was considered low because the data were derived mostly from observational or cohort studies (Supplementary Table S4).

4. Discussion

Our meta-analysis of the serologic response to the COVID-19 vaccine in SOT recipients showed that less than 10% of transplant recipients seroconverted following one dose of COVID-19 vaccination. The rate improved to 34% following the second dose. In comparison to controls, the seroconversion rates were lower following both doses. A third booster shot, which has recently been approved, improved the rate to 66%, but in a subset of patients who had not achieved a response after two doses, it remained low at 36%. The results of our study suggest that there is a need for a more effective prophylaxis strategy in SOT patients.

Patients with a history of SOT are at higher risk for COVID-19 and its mortality [38]. Transplant recipients are immunocompromised due to the long-term use of immunosuppressive medications. Immunosuppressive drugs may influence the functions of B and T cells that lower the response to vaccinations [21,23,39]. Furthermore, transplant recipients are generally older and may carry comorbidities that increase the risk of COVID-19.

The study by Shroti et al., reported that 96–99% of patients in the general community seroconverted following a single or two series of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 or BNT162b2 vaccines. In their study, elderly individuals and those with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or cancer were less likely to achieve antibody response [40]. In our study, the serologic response rates of SOT patients following one or two doses of COVID-19 vaccination was 9% and 34%, respectively, which were lower than those reported in a meta-analysis of immune mediated inflammatory disease patients receiving biologics [23]. When compared to controls, the odds of seroconversion among transplant recipients were lower after both doses. The proportion of patients on GC therapy was associated with lower response following one dose whereas advanced age was associated with lower response in addition to GC use following two doses. This suggests that additional patient and treatment factors may be associated with a weakened vaccine response in transplant recipients, which warrants further investigation.

The low serologic response rates to the two-dose mRNA vaccination strategy in transplant recipients led us to investigate the response to the booster (third) vaccination. The response rate after the third dose rose to 65%, but was still suboptimal. Furthermore, among a subset of patients who failed to seroconvert after two doses, merely a third seroconverted after the third dose. AD26.COV2.S mounted a weaker serologic response, but AZD1222 or mRNA-1273 induced a stronger response in subgroup analyses, so studies of different hybrid regimens or doses are warranted [41,42]. Future studies will need to assess strategies for prophylaxis including the use of monoclonal Antibody (mAb)-based immune prophylaxis as a substitute or as a complement to vaccines in SOT recipients.

5. Limitations

Although it has been more than a year since the first vaccine was approved against COVID-19, available reports on transplant recipients were rather limited and mostly consisted of studies of a small sample size. There are currently nine COVID-19 vaccinations available for use globally, but a majority of the studies included in our meta-analysis were of either mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2, and a small number of studies were of AD26.COV2.S or AZD-1222/ChAdOx1 nCoV-19. Our primary outcome was a humoral response to vaccines; however, we could not evaluate the difference in T cell-mediated immune response due to the of data. Recent studies have reported that levels of antibodies can be predictive of the risk of infections in healthy individuals and that those who are immunocompromised were at greater risk of post-vaccination infections, so we consider that our meta-analysis focusing on serologic response provides meaningful information [43,44]. Further studies assessing whether the incomplete serologic response to vaccination would prevent symptomatic or severe COVID-19 in SOT patients are also warranted [45,46]. Due to the limited data, we were unable to undertake subgroup analyses according to different immunosuppressive therapies. Furthermore, the studies included in our meta-analysis were somewhat heterogeneous regarding transplanted organ(s), size of the sample, treatment, timing, and type of test used to measure antibody levels. A majority of studies included in our analysis used either the antibody test marketed by Abbott, DiaSorin, or Roche. They are all known to have a sensitivity of 98 to 100% [24]. Consequently, the results of antibody testing have an excellent correlation in regard to seroprevalence. Recent reports have shown declining antibody levels after 3–8 weeks of second vaccination in patients receiving ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 or BNT162b2 [47], so further research assessing the waning of antibodies in immunocompromised and transplant patients is warranted.

6. Conclusions

We have demonstrated that the rate of seroconversion to vaccinations against COVID-19 in SOT recipients was only 9% and 34% following the first and second dose. The rate improved to 66% following the third booster injection. However, in a subset of patients who had not achieved a response after two doses only a third achieved a response with the third dose. The results of our study suggest the urgent need for an improved prophylaxis strategy including the use of mAb-based immune prophylaxis as a substitute or as a complement to vaccines in this vulnerable patient population and that they need to continue following safety measures.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/v14081822/s1, Figure S1: A. Serologic response after one dose of vaccine: Ad26.COV2.S vaccine, Figure S2: A. Funnel plot of studies included in meta-analysis of serologic response after one dose of vaccine, Figure S3: A. Funnel plot of studies included in meta-analysis of serologic response after two doses of vaccine, Figure S4: A. Funnel plot of studies included in meta-analysis of comparison of serologic response after one dose of vaccine compared to controls, Figure S5: A. Funnel plot of studies included in meta-analysis of serologic response after three doses of vaccine, Figure S6: Funnel plot of studies included in meta-analysis of serologic response after three doses of vaccine among non-responders to two doses, Table S1: Risk of bias assessment by Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist, Table S2: Univariate and multivariate meta-regression models of variables associated with serologic response after one dose of mRNA vaccine, Table S3: Univariate and multivariate meta-regression models of variables associated with serologic response after two doses of mRNA vaccine, Table S4: Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria for studies included in the meta-analysis.

Author Contributions

A.S.; design of project, collection and analysis of data, drafting of manuscript, full responsibility of the published article, A.L.; collection and analysis of data, D.M.; interpretation of data and drafting of manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, N.; Zhou, M.; Dong, X.; Qu, J.; Gong, F.; Han, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet 2020, 395, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sato, T.; Sakuraba, A. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Meets Obesity: Strong Association between the Global Overweight Population and COVID-19 Mortality. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salto-Alejandre, S.; Jimenez-Jorge, S.; Sabe, N.; Ramos-Martinez, A.; Linares, L.; Valerio, M.; Martin-Davila, P.; Fernandez-Ruiz, M.; Farinas, M.C.; Blanes-Julia, M.; et al. Risk factors for unfavorable outcome and impact of early post-transplant infection in solid organ recipients with COVID-19: A prospective multicenter cohort study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojciechowski, D.; Wiseman, A. Long-Term Immunosuppression Management: Opportunities and Uncertainties. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 16, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilch, N.A.; Bowman, L.J.; Taber, D.J. Immunosuppression trends in solid organ transplantation: The future of individualization, monitoring, and management. Pharmacotherapy 2021, 41, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ Donation Statistics. Available online: https://www.organdonor.gov/learn/organ-donation-statistics (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Roberts, M.B.; Fishman, J.A. Immunosuppressive Agents and Infectious Risk in Transplantation: Managing the “Net State of Immunosuppression”. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e1302–e1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, J.A. Infection in Organ Transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 856–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronbichler, A.; Gauckler, P.; Windpessl, M.; Il Shin, J.; Jha, V.; Rovin, B.H.; Oberbauer, R. COVID-19: Implications for immunosuppression in kidney disease and transplantation. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Perez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, H. Six months of COVID vaccines: What 1.7 billion doses have taught scientists. Nature 2021, 594, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, L.A.; Anderson, E.J.; Rouphael, N.G.; Roberts, P.C.; Makhene, M.; Coler, R.N.; McCullough, M.P.; Chappell, J.D.; Denison, M.R.; Stevens, L.J.; et al. An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2-Preliminary Report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1920–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stucchi, R.S.B.; Lopes, M.H.; Kumar, D.; Manuel, O. Vaccine Recommendations for Solid-Organ Transplant Recipients and Donors. Transplantation 2018, 102, S72–S80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyarsky, B.J.; Werbel, W.A.; Avery, R.K.; Tobian, A.A.R.; Massie, A.B.; Segev, D.L.; Garonzik-Wang, J.M. Immunogenicity of a Single Dose of SARS-CoV-2 Messenger RNA Vaccine in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. JAMA 2021, 325, 1784–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massa, F.; Cremoni, M.; Gerard, A.; Grabsi, H.; Rogier, L.; Blois, M.; Couzin, C.; Hassen, N.B.; Rouleau, M.; Barbosa, S.; et al. Safety and cross-variant immunogenicity of a three-dose COVID-19 mRNA vaccine regimen in kidney transplant recipients. EBioMedicine 2021, 73, 103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masset, C.; Kerleau, C.; Garandeau, C.; Ville, S.; Cantarovich, D.; Hourmant, M.; Kervella, D.; Houzet, A.; Guillot-Gueguen, C.; Guihard, I.; et al. A third injection of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients improves the humoral immune response. Kidney Int. 2021, 100, 1132–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A. PROSPERO’s progress and activities 2012/13. Syst. Rev. 2013, 2, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.M.Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. 2020. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Sakuraba, A.; Luna, A.; Micic, D. Serologic response following SARS-COV2 vaccination in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Montori, V.; Akl, E.A.; Djulbegovic, B.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence--study limitations (risk of bias). J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuraba, A.; Luna, A.; Micic, D. Serologic Response to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccination in Patients With Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 88–108.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Meo, A.; Miller, J.J.; Fabros, A.; Brinc, D.; Hall, V.; Pinzon, N.; Ierullo, M.; Ku, T.; Ferreira, V.H.; Kumar, D.; et al. Evaluation of Three Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Serologic Immunoassays for Post-Vaccine Response. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2022, 7, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 5.1.0.; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Begg, C.B.; Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994, 50, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clyne, B.; Walsh, K.A.; O’Murchu, E.; Sharp, M.K.; Comber, L.; KK, O.B.; Smith, S.M.; Harrington, P.; O’Neill, M.; Teljeur, C.; et al. Using preprints in evidence synthesis: Commentary on experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 138, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarot, N.; Morel, A.; Leruez-Ville, M.; Vilain, E.; Divard, G.; Burger, C.; Serris, A.; Sberro-Soussan, R.; Martinez, F.; Amrouche, L.; et al. Weak antibody response to three doses of mRNA vaccine in kidney transplant recipients treated with belatacept. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 4043–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, V.G.; Ferreira, V.H.; Ku, T.; Ierullo, M.; Majchrzak-Kita, B.; Chaparro, C.; Selzner, N.; Schiff, J.; McDonald, M.; Tomlinson, G.; et al. Randomized Trial of a Third Dose of mRNA-1273 Vaccine in Transplant Recipients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1244–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, Y.; Ram, E.; Lavee, J.; Segev, A.; Matezki, S.; Wieder-Finesod, A.; Halperin, R.; Mandelboim, M.; Indenbaum, V.; Levy, I.; et al. Third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine in heart transplant recipients: Immunogenicity and clinical experience. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2022, 41, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benotmane, I.; Gautier, G.; Perrin, P.; Olagne, J.; Cognard, N.; Fafi-Kremer, S.; Caillard, S. Antibody Response After a Third Dose of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Kidney Transplant Recipients With Minimal Serologic Response to 2 Doses. JAMA 2021, 326, 1063–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bello, A.; Abravanel, F.; Marion, O.; Couat, C.; Esposito, L.; Lavayssiere, L.; Izopet, J.; Kamar, N. Efficiency of a boost with a third dose of anti-SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA-based vaccines in solid organ transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2022, 22, 322–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmetant, X.; Espi, M.; Barba, T.; Ovize, A.; Morelon, E.; Thaunat, O. Predictive factors of response to 3rd dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine in kidney transplant recipients. medRxiv 10.1101/2021.08.23.21262293, 2021.2008.2023.21262293. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhoff, T.H.; Seibert, F.S.; Anft, M.; Blazquez-Navarro, A.; Skrzypczyk, S.; Zgoura, P.; Meister, T.L.; Pfaender, S.; Stumpf, J.; Hugo, C.; et al. A third vaccine dose substantially improves humoral and cellular SARS-CoV-2 immunity in renal transplant recipients with primary humoral nonresponse. Kidney Int. 2021, 100, 1135–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrezenmeier, E.; Rincon-Arevalo, H.; Stefanski, A.L.; Potekhin, A.; Straub-Hohenbleicher, H.; Choi, M.; Bachmann, F.; Pross, V.; Hammett, C.; Schrezenmeier, H.; et al. B and T Cell Responses after a Third Dose of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Kidney Transplant Recipients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 32, 3027–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamode, N.; Ahmed, Z.; Jones, G.; Banga, N.; Motallebzadeh, R.; Tolley, H.; Marks, S.; Stojanovic, J.; Khurram, M.A.; Thuraisingham, R.; et al. Mortality Rates in Transplant Recipients and Transplantation Candidates in a High-prevalence COVID-19 Environment. Transplantation 2021, 105, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsit, J.F.; Sonneville, R.; Kalil, A.C.; Bassetti, M.; Ferrer, R.; Jaber, S.; Lanternier, F.; Luyt, C.E.; Machado, F.; Mikulska, M.; et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to infectious diseases in solid organ transplant recipients. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrotri, M.; Fragaszy, E.; Geismar, C.; Nguyen, V.; Beale, S.; Braithwaite, I.; Byrne, T.E.; Erica Fong, W.L.; Kovar, J.; Navaratnam, A.M.D.; et al. Spike-antibody responses to ChAdOx1 and BNT162b2 vaccines by demographic and clinical factors (Virus Watch study). medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natori, Y.; Shiotsuka, M.; Slomovic, J.; Hoschler, K.; Ferreira, V.; Ashton, P.; Rotstein, C.; Lilly, L.; Schiff, J.; Singer, L.; et al. A Double-Blind, Randomized Trial of High-Dose vs. Standard-Dose Influenza Vaccine in Adult Solid-Organ Transplant Recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 1698–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, D.; Purcell, L.A.; Snell, G.; Veesler, D. Tackling COVID-19 with neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Cell 2021, 184, 3086–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, D.S.; Cromer, D.; Reynaldi, A.; Schlub, T.E.; Wheatley, A.K.; Juno, J.A.; Subbarao, K.; Kent, S.J.; Triccas, J.A.; Davenport, M.P. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergwerk, M.; Gonen, T.; Lustig, Y.; Amit, S.; Lipsitch, M.; Cohen, C.; Mandelboim, M.; Levin, E.G.; Rubin, C.; Indenbaum, V.; et al. Covid-19 Breakthrough Infections in Vaccinated Health Care Workers. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1474–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemaitelly, H.; AlMukdad, S.; Joy, J.P.; Ayoub, H.H.; Yassine, H.M.; Benslimane, F.M.; Al Khatib, H.A.; Tang, P.; Hasan, M.R.; Coyle, P.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine effectiveness in immunosuppressed kidney transplant recipients. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A.R.; Kobayashi, T.; Suzuki, H.; Alsuhaibani, M.; Tofaneto, B.M.; Bariani, L.M.; Auler, M.A.; Salinas, J.L.; Edmond, M.B.; Doll, M.; et al. Short-term effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in immunocompromised patients: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2022, 84, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrotri, M.; Navaratnam, A.M.D.; Nguyen, V.; Byrne, T.; Geismar, C.; Fragaszy, E.; Beale, S.; Fong, W.L.E.; Patel, P.; Kovar, J.; et al. Spike-antibody waning after second dose of BNT162b2 or ChAdOx1. Lancet 2021, 398, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).