Potential Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Therapeutics That Target the Post-Entry Stages of the Viral Life Cycle: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

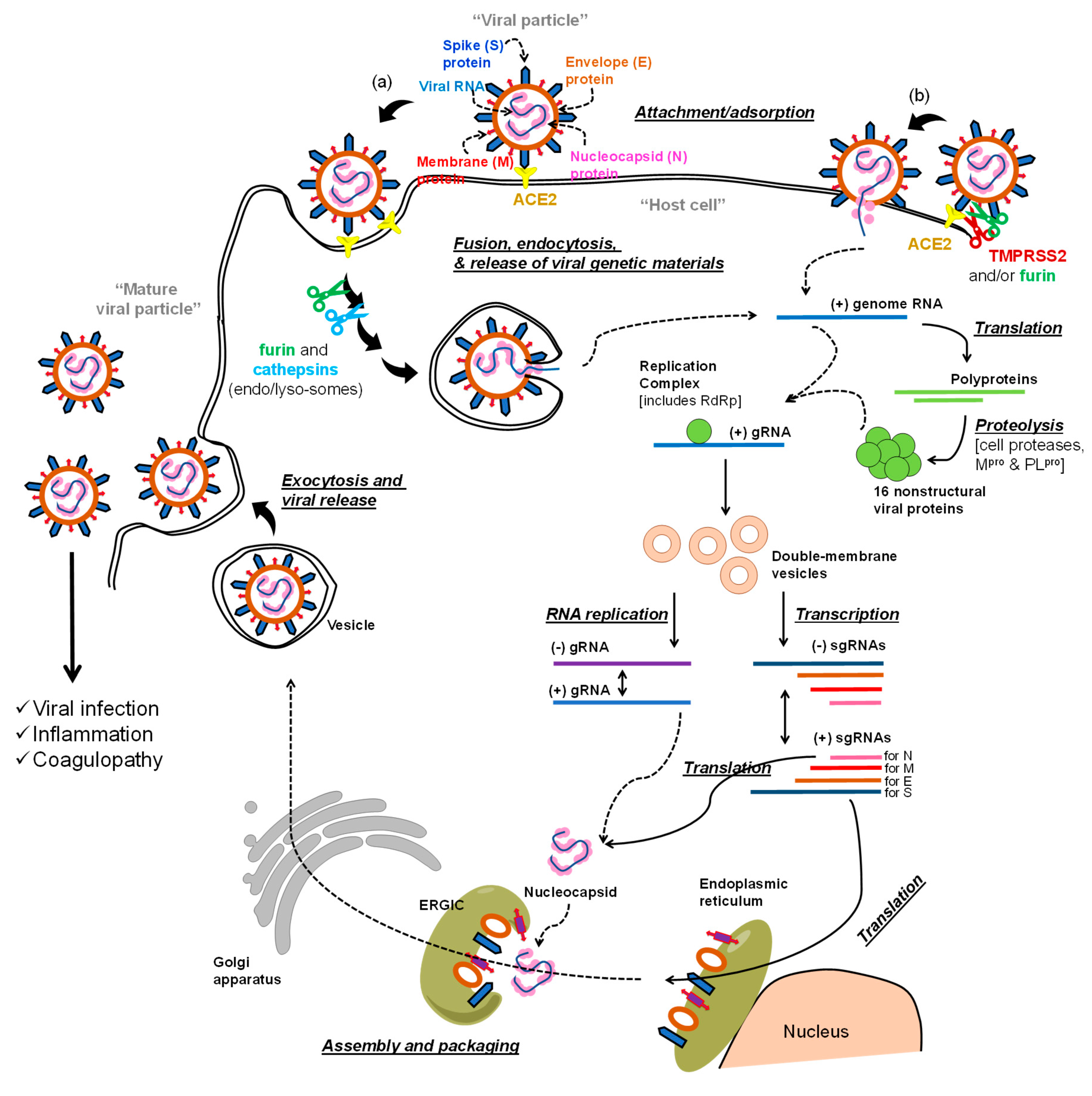

The Life Cycle of SARS-COV-2 and Potential Targets for Drug Development

2. Viral Polymerase Inhibitors

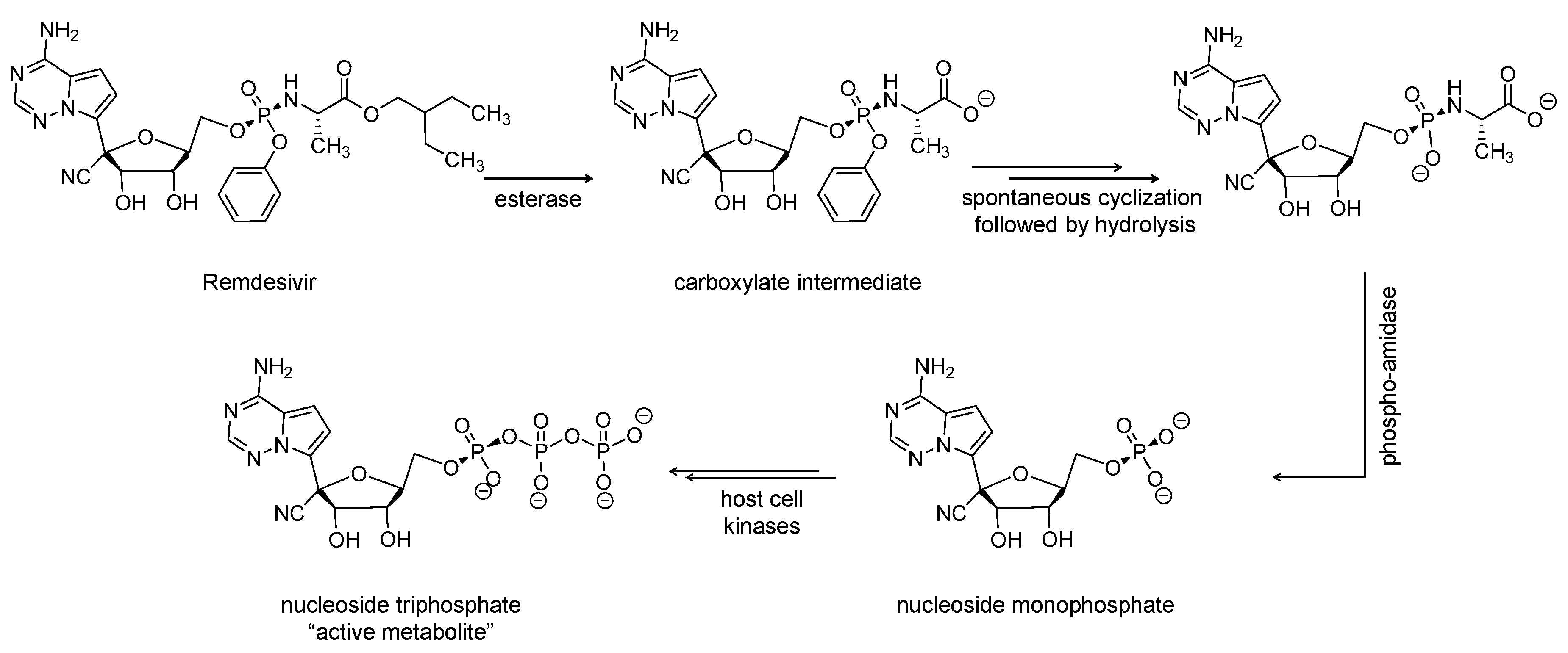

2.1. Remdesivir (Veklury, GS-5734)

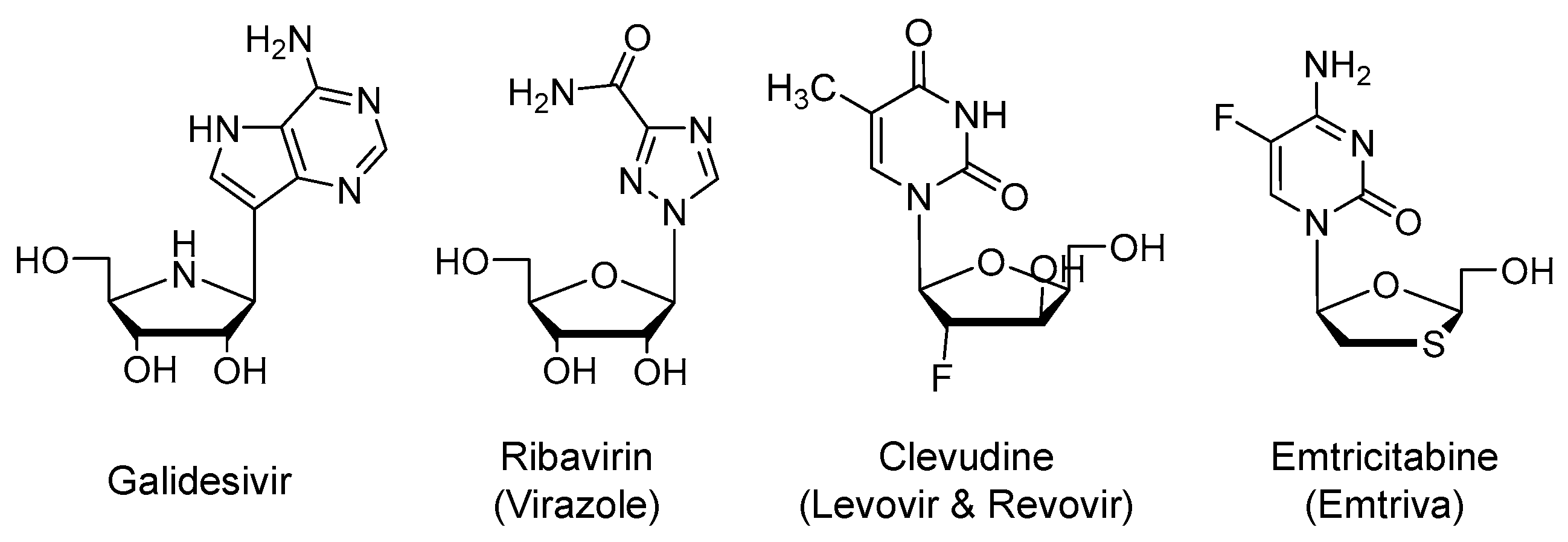

2.2. Galidesivir (Immucillin-A, BCX4430)

2.3. Ribavirin (Virazole)

2.4. Clevudine (Levovir and Revovir)

2.5. Emtricitabine (Emtriva) in Combination with Tenofovir Disoproxil or Tenofovir Alafenamide

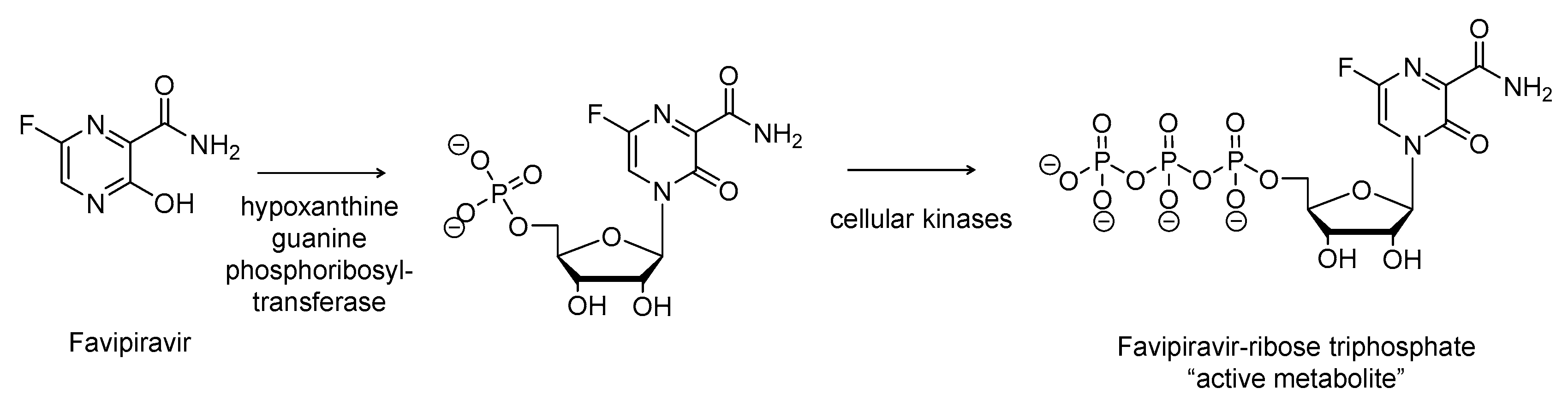

2.6. Favipiravir (Avigan, T-705)

2.7. AT-527

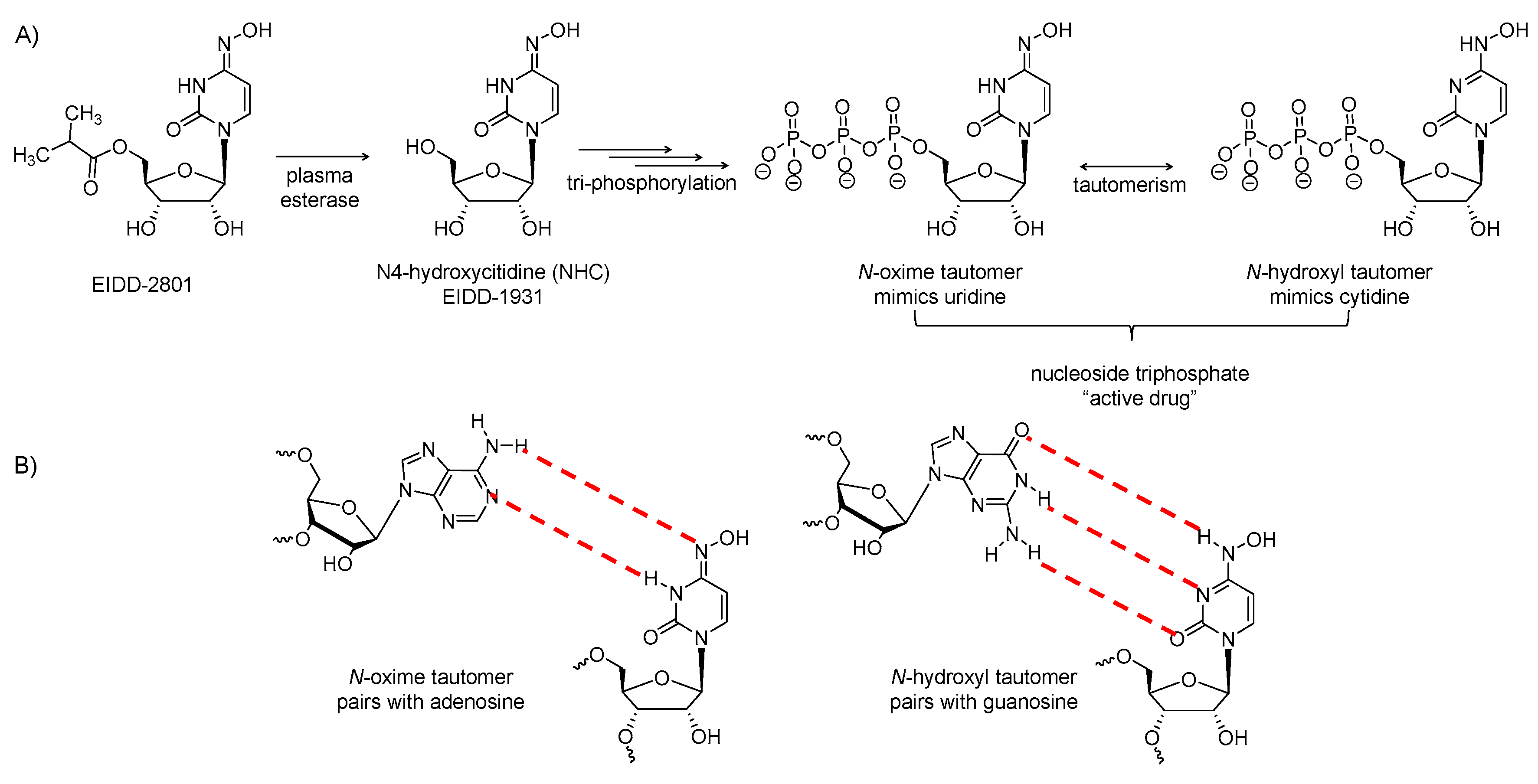

2.8. EIDD-2801

3. Viral Protease Inhibitors

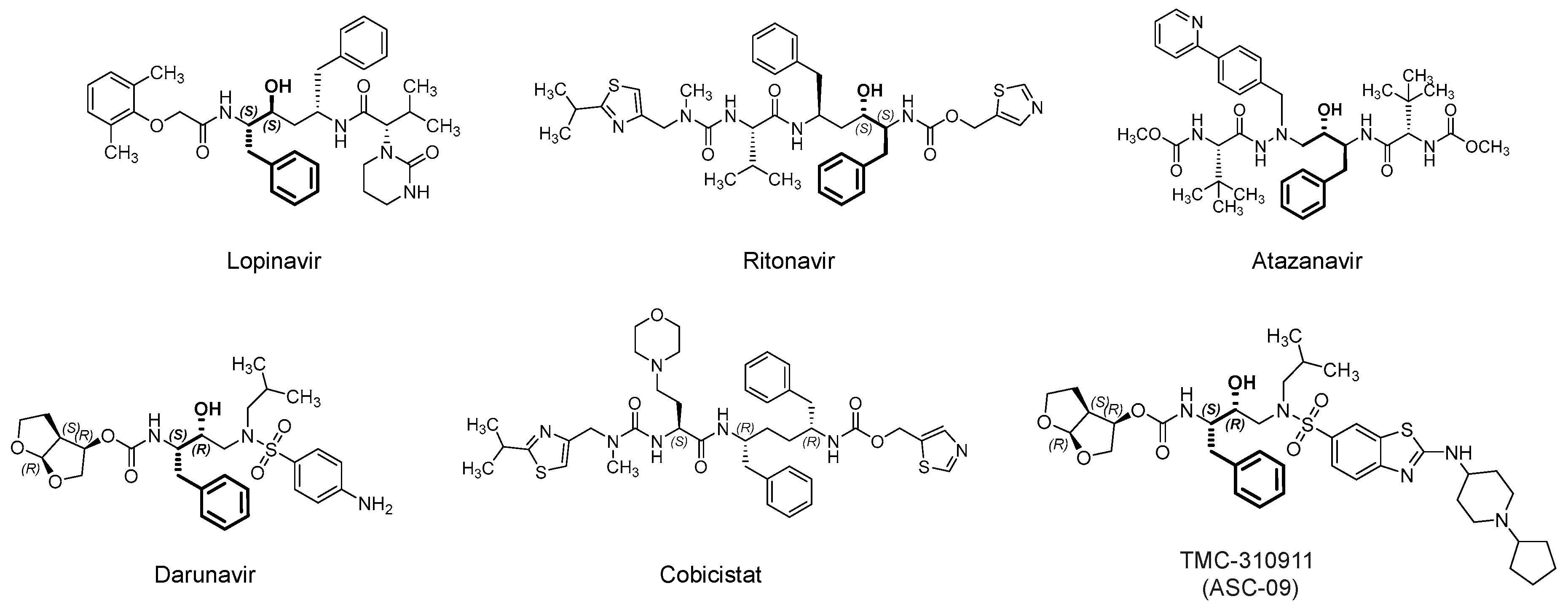

3.1. Lopinavir/Ritonavir (Kaletra)

3.2. Darunavir/Cobicistat (Prezcobix)

3.3. Atazanavir (Reyataz)

3.4. Danoprevir/Ritonavir

3.5. Maraviroc (Selzentry)

4. Miscellaneous Antiviral Agents

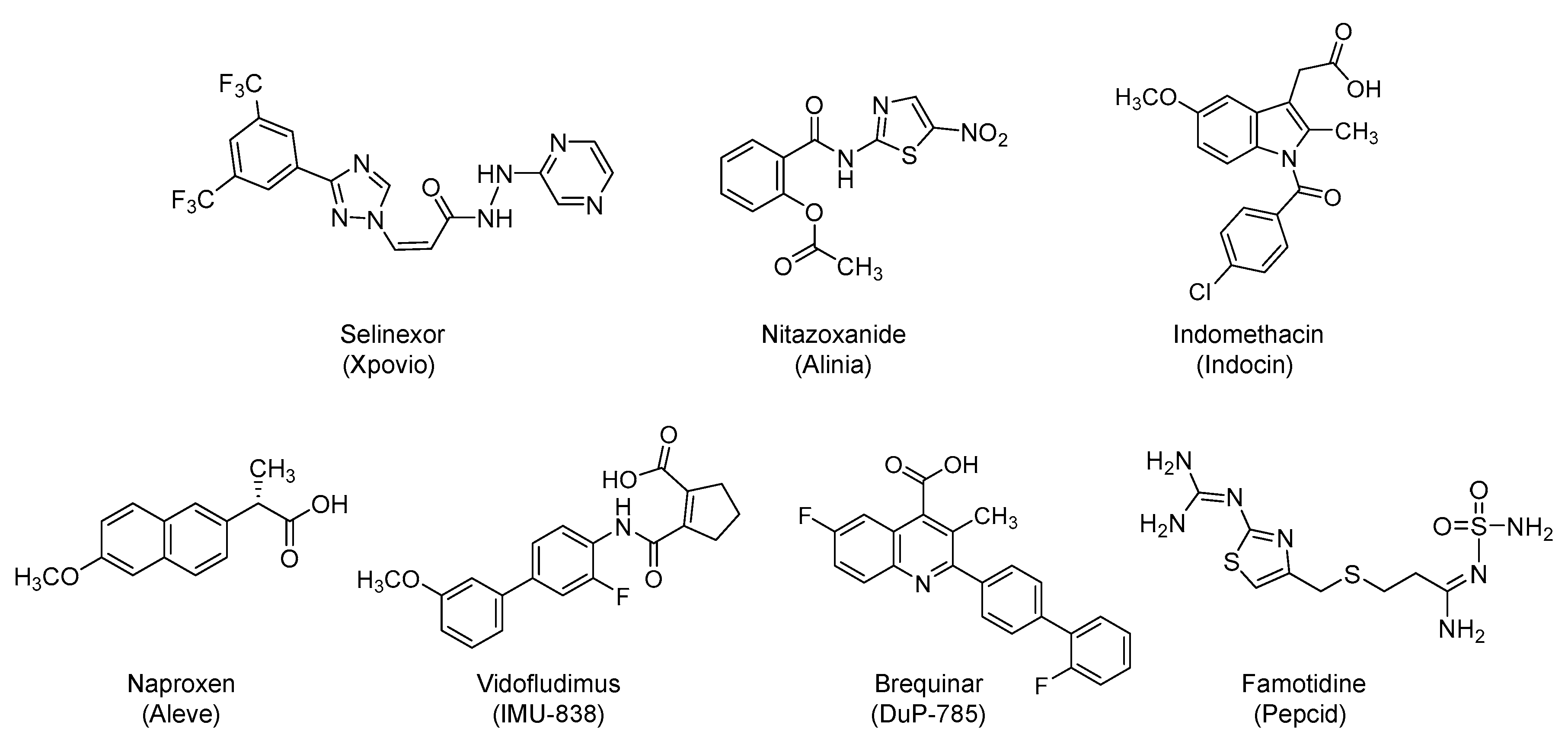

4.1. Selinexor (Xpovio, KPT330)

4.2. Nitazoxanide (Alinia)

4.3. NSAIDs: Indomethacin (Indocin) and Naproxen (Aleve)

4.4. Vidofludimus Calcium (Immunic AG, IMU-838) and Brequinar (DuP-785)

4.5. Famotidine (Pepcid)

4.6. VERU-111

4.7. Leflunomide (Arava)

4.8. Sirolimus (Rapamune)

4.9. Plitidepsin (Aplidin)

4.10. Cyclosporine A (Gengraf)

4.11. Deferoxamine (Desferal)

4.12. Atovaquone (Mepron)

4.13. Levamisole

4.14. BLD-2660

4.15. N-Acetylcysteine (Acetadote)

4.16. Artesunate

4.17. Povidone-Iodine Solution (Betadine)

4.18. Chlorhexidine (Peridex)

4.19. Methylene Blue (ProvayBlue)

4.20. Inhaled Nitric Oxide

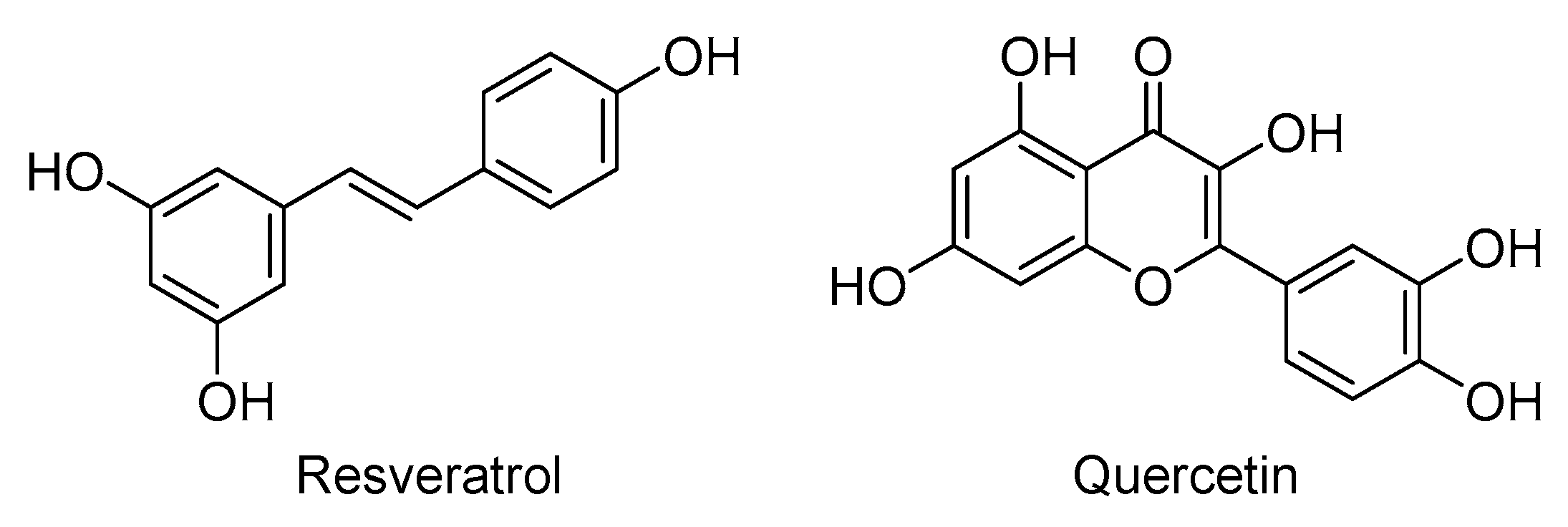

4.21. Poly-Alcohols: Resveratrol and Quercetin

4.22. Macromolecules: Thymalfasin, Lactoferrin, TY027, and XAV-19

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3CLpro | 3-Chymotrypsin-like protease |

| ACE2 | Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 |

| ADALP1 | Adenosine deaminase like protein 1 |

| CES1 | Carboxylesterase 1 |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus infectious disease of 2019 |

| CRM1 | Chromosome region maintenance 1 |

| ERGIC | Endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi intermediate compartment |

| GTP | Guanosine triphosphate |

| GUK1 | Guanylate kinase 1 |

| HINT1 | Histidine triad nucleotide-binding protein 1 |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| INF | Interferon |

| IL | Interleukin |

| MERS-CoV | Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus |

| Mpro | Main protease |

| NDPK | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| NSP | Nonstructural protein |

| NF-AT | Nuclear factor of activated T-cells |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| PLpro | Papain-like protease |

| RdRp | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase |

| SARS-CoV | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 |

| TRMPSS2 | Transmembrane protease serine 2 |

References

- Peiris, J.S.; Yuen, K.Y.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Stöhr, K. The severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 2431–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, R.J.; Baker, S.C.; Baric, R.S.; Brown, C.S.; Drosten, C.; Enjuanes, L.; Fouchier, R.A.; Galiano, M.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Memish, Z.A.; et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Announcement of the Coronavirus Study Group. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 7790–7792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: Classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, E.; Du, H.; Gardner, L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 533–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhong, W.; Bian, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, K.; Liang, B.; Zhong, Y.; Hu, M.; Lin, L.; Liu, J.; et al. A comparison of mortality-related risk factors of COVID-19, SARS, and MERS: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020, 81, e18–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ruch, Y.; Kaeuffer, C.; Guffroy, A.; Lefebvre, N.; Hansmann, Y.; Danion, F. Rapid Radiological Worsening and Cytokine Storm Syndrome in COVID-19 Pneumonia. Eur. J. Case. Rep. Intern. Med. 2020, 7, 001822. [Google Scholar]

- Marietta, M.; Coluccio, V.; Luppi, M. COVID-19, coagulopathy and venous thromboembolism: More questions than answers. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Health. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Antiviral Therapy. Available online: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/antiviral-therapy/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Russian Direct Investment Fund. Available online: https://rdif.ru/Eng_fullNews/5220/ (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- National Institute of Health. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Corticosteroids. Available online: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/dexamethasone/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Al-Horani, R.A.; Kar, S.; Aliter, K.F. Potential Anti-COVID-19 Therapeutics that Block the Early Stage of the Viral Life Cycle: Structures, Mechanisms, and Clinical Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Ye, G.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11727–11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Pöhlmann, S.A. Multibasic cleavage site in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for infection of human lung cells. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 779.e5–784.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Luo, S.; Libby, P.; Shi, G.P. Cathepsin L-selective inhibitors: A potentially promising treatment for COVID-19 patients. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 213, 107587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khailany, R.A.; Safdar, M.; Ozaslan, M. Genomic characterization of a novel SARS-CoV-2. Gene Rep. 2020, 19, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astuti, I.; Ysrafil. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): An overview of viral structure and host response. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lin, D.; Sun, X.; Curth, U.; Drosten, C.; Sauerhering, L.; Becker, S.; Rox, K.; Hilgenfeld, R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science 2020, 368, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yan, L.; Huang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, L.; Wang, T.; Sun, Q.; Ming, Z.; Zhang, L.; et al. Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from COVID-19 virus. Science 2020, 368, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Hillyer, C.; Du, L. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atri, D.; Siddiqi, H.K.; Lang, J.; Nauffal, V.; Morrow, D.A.; Bohula, E.A. COVID-19 for the Cardiologist: A Current Review of the Virology, Clinical Epidemiology, Cardiac and Other Clinical Manifestations and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. JACC: Basic Transl. Sci. 2020, 5, 518–536. [Google Scholar]

- Du, L.; He, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Zheng, B.-J.; Jiang, S. The spike protein of SARS-CoV--a target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/137564/download (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Scavone, C.; Brusco, S.; Bertini, M.; Sportiello, L.; Rafaniello, C.; Zoccoli, A.; Berrino, L.; Racagni, G.; Rossi, F.; Capuano, A. Current pharmacological treatments for COVID-19: What’s next? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, T.K.; Jordan, R.; Lo, M.K.; Ray, A.S.; Mackman, R.L.; Soloveva, V.; Siegel, D.; Perron, M.; Bannister, R.; Hui, H.C.; et al. Therapeutic efficacy of the small molecule GS-5734 against Ebola virus in rhesus monkeys. Nature 2016, 531, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheahan, T.P.; Sims, A.C.; Graham, R.L.; Menachery, V.D.; Gralinski, L.E.; Case, J.B.; Leist, S.R.; Pyrc, K.; Feng, J.Y.; Trantcheva, I.; et al. Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaal3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, R.T.; Roth, J.S.; Brimacombe, K.R.; Simeonov, A.; Shen, M.; Patnaik, S.; Hall, M.D. Remdesivir: A Review of Its Discovery and Development Leading to Emergency Use Authorization for Treatment of COVID-19. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.J.; Tchesnokov, E.P.; Feng, J.Y.; Porter, D.P.; Götte, M. The antiviral compound remdesivir potently inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 4773–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.J.; Tchesnokov, E.P.; Woolner, E.; Perry, J.K.; Feng, J.Y.; Porter, D.P.; Götte, M. Remdesivir is a direct-acting antiviral that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with high potency. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 6785–6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferner., R.E.; Aronson, J.K. Remdesivir in covid-19. BMJ 2020, 369, m1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cao, R.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, M.; Shi, Z.; Hu, Z.; Zhong, W.; Xiao, G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheahan, T.P.; Sims, A.C.; Leist, S.R.; Schäfer, A.; Won, J.; Brown, A.J.; Montgomery, S.A.; Hogg, A.; Babusis, D.; Clarke, M.O.; et al. Comparative therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir and combination lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon beta against MERS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, E.; Feldmann, F.; Cronin, J.; Jordan, R.; Okumura, A.; Thomas, T.; Scott, D.; Cihlar, T.; Feldmann, H. Prophylactic and therapeutic remdesivir (GS-5734) treatment in the rhesus macaque model of MERS-CoV infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 6771–6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruijssers, A.J.; George, A.S.; Schäfer, A.; Leist, S.R.; Gralinksi, L.E.; Dinnon, K.H.; Yount, B.L.; Agostini, M.L.; Stevens, L.J.; Chappell, J.D.; et al. Remdesivir Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 in Human Lung Cells and Chimeric SARS-CoV Expressing the SARS-CoV-2 RNA Polymerase in Mice. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 107940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Du, G.; Du, R.; Zhao, J.; Jin, Y.; Fu, S.; Gao, L.; Cheng, Z.; Lu, Q.; et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, J.D.; Lye, D.; Hui, D.S.; Marks, K.M.; Bruno, R.; Montejano, R.; Spinner, C.D.; Galli, M.; Ahn, M.-Y.; Nahass, R.G.; et al. Remdesivir for 5 or 10 Days in Patients with Severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grein, J.; Ohmagari, N.; Shin, D.; Diaz, G.; Asperges, E.; Castagna, A.; Feldt, T.; Green, G.; Green, M.L.; Lescure, F.X.; et al. Compassionate Use of Remdesivir for Patients with Severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2327–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Institutes of Health. NIH clinical trial shows remdesivir accelerates recovery from advanced COVID-19. Press release; 2020. Available online: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-clinical-trial-shows-remdesivir-accelerates-recovery-advanced-covid-19 (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- The U.S. National Institutes of Health. Remdesivir. Available online: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/antiviral-therapy/remdesivir/ (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of Veklury® (remdesivir). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/137566/download (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Gilead Sciences. Press Release: Gilead Presents Additional Data on Investigational Antiviral Remdesivir for the Treatment of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.gilead.com/news-and-press/press-room/press-releases/2020/7/gilead-presents-additional-data-on-investigational-antiviral-remdesivir-for-the-treatment-of-covid-19 (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Warren, T.K.; Wells, J.; Panchal, R.G.; Stuthman, K.S.; Garza, N.L.; Van Tongeren, S.A.; Dong, L.; Retterer, C.J.; Eaton, B.P.; Pegoraro, G.; et al. Protection against filovirus diseases by a novel broad-spectrum nucleoside analogue BCX4430. Nature 2014, 508, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westover, J.B.; Mathis, A.; Taylor, R.; Wandersee, L.; Bailey, K.W.; Sefing, E.J.; Hickerson, B.T.; Jung, K.-H.; Sheridan, W.P.; Gowen, B.B. Galidesivir limits Rift Valley fever virus infection and disease in Syrian golden hamsters. Antivir. Res. 2018, 156, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biocryst. Glidesivir. Available online: https://www.biocryst.com/our-program/galidesivir/ (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Julander, J.G.; Siddharthan, V.; Evans, J.; Taylor, R.; Tolbert, K.; Apuli, C.; Stewart, J.; Collins, P.; Gebre, M.; Neilson, S.; et al. Efficacy of the broad-spectrum antiviral compound BCX4430 against Zika virus in cell culture and in a mouse model. Antivir. Res. 2017, 137, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, T.P.; Whalen, M.; Hilts-Horeczko, A.; Doernberg, S.B.; Liu, C. Comparative effectiveness of aerosolized versus oral ribavirin for the treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infections: A single-center retrospective cohort study and review of the literature. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2018, 20, e12844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienstag, J.L.; McHutchison, J.G. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergönül, Ö.; Keske, Ş.; Çeldir, M.G.; Kara, I.A.; Pshenichnaya, N.; Abuova, G.; Blumberg, L.; Gönen, M. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Postexposure Prophylaxis for Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus among Healthcare Workers. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 1642–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, C.E.; Castro, C. The mechanism of action of ribavirin: Lethal mutagenesis of RNA virus genomes mediated by the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 14, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Te, H.S.; Randall, G.; Jensen, D.M. Mechanism of action of ribavirin in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 3, 218–225. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P.; Jensen, D.M. Ribavirin in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 23, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Chang, M.; Saab, S. Management of hepatitis C antiviral therapy adverse effects. Curr. Hepat. Rep. 2011, 10, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfiky, A.A. Ribavirin, Remdesivir, Sofosbuvir, Galidesivir, and Tenofovir against SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp): A molecular docking study. Life Sci. 2020, 253, 117592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzarano, D.; De Wit, E.; Rasmussen, A.L.; Feldmann, F.; Okumura, A.; Scott, D.P.; Brining, D.; Bushmaker, T.; Martellaro, C.; Baseler, L.; et al. Treatment with interferon-α2b and ribavirin improves outcome in MERS-CoV-infected rhesus macaques. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1313–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabi, Y.M.; Mandourah, Y.; Al-Hameed, F.; Sindi, A.A.; Almekhlafi, G.A.; Hussein, M.A.; Jose, J.; Pinto, R.; Al-Omari, A.; Kharaba, A.; et al. Corticosteroid Therapy for Critically Ill Patients with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.L.; Ooi, E.E.; Lin, C.-Y.; Tan, H.C.; Ling, A.E.; Lim, B.; Stanton, L.W. Inhibition of SARS coronavirus infection in vitro with clinically approved antiviral drugs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, I.F.; Lung, K.C.; Tso, E.Y.; Liu, R.; Chung, T.W.; Chu, M.Y.; Ng, Y.Y.; Lo, J.; Chan, J.; Tam, A.R.; et al. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir-ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: An open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.-H.; Kim, J.-W.; Jeong, S.H.; Myung, H.-J.; Kim, H.S.; Park, Y.S.; Lee, S.H.; Hwang, J.-H.; Kim, N.; Lee, D.H. Clevudine for chronic hepatitis B: Antiviral response, predictors of response, and development of myopathy. J. Viral. Hepat. 2011, 18, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.A.; Murakami, E.; Delaney, W.; Furman, P.; Hu, J. Noncompetitive inhibition of hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase protein priming and DNA synthesis by the nucleoside analog clevudine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 4181–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information for Emtriva. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/021500s019lbl.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Frampton, J.E.; Perry, C.M. Emtricitabine: A review of its use in the management of HIV infection. Drugs 2005, 65, 1427–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, R.A.; Valentovic, M.A. Factors Contributing to the Antiviral Effectiveness of Tenofovir. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2017, 363, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buti, M.; Tsai, N.; Petersen, J.; Flisiak, R.; Gurel, S.; Krastev, Z.; Aguilar Schall, R.; Flaherty, J.F.; Martins, E.B.; Charuworn, P.; et al. Seven-year efficacy and safety of treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copertino, D.C., Jr.; Lima, B.; Duarte, R.; Wilkin, T.; Gulick, R.; De Mulder Rougvie, M.; Nixon, D. Antiretroviral Drug Activity and Potential for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Against COVID-19 and HIV Infection. ChemRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkus, G.; Bam, R.A.; Willkom, M.; Frey, C.R.; Tsai, L.; Stray, K.M.; Yant, S.R.; Cihlar, T. Intracellular Activation of Tenofovir Alafenamide and the Effect of Viral and Host Protease Inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 60, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, S.; Kurosaki, M.; Tamaki, N.; Itakura, J.; Hayashi, T.; Kirino, S.; Osawa, L.; Watakabe, K.; Okada, M.; Wang, W.; et al. Tenofovir alafenamide for hepatitis B virus infection including switching therapy from tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 34, 2004–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, Y.; Komeno, T.; Nakamura, T. Favipiravir (T-705), a broad-spectrum inhibitor of viral RNA polymerase. Proc. Jpn. Acad. B. 2017, 93, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naesens, L.; Guddat, L.W.; Keough, D.T.; Van Kuilenburg, A.B.P.; Meijer, J.; Voorde, J.V.; Balzarini, J. Role of human hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase in activation of the antiviral agent T-705 (favipiravir). Mol. Pharmacol. 2013, 84, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Shiraki, K.; Sakamoto, K.; Smee, D.F.; Barnard, D.L.; Gowen, B.B.; Julander, J.G.; Morrey, J.D. T-705 (favipiravir) and related compounds: Novel broad-spectrum inhibitors of RNA viral infections. Antiviral Res. 2009, 82, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sissoko, D.; Laouenan, C.; Folkesson, E.; M’Lebing, A.B.; Beavogui, A.H.; Baize, S.; Camara, A.-M.; Maes, P.; Shepherd, S.; Danel, C.; et al. Experimental treatment with favipiravir for Ebola virus disease (the JIKI Trial): A historically controlled, single-arm proof-of-concept trial in Guinea. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Q.; Yang, M.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.; Shu, D.; Xia, J.; Liao, X.; Gu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Yang, Y.; et al. Experimental Treatment with Favipiravir for COVID-19: An Open-Label Control Study. Engineering 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Huang, J.; Yin, P.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Z.-S.; Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, B.; Lu, M.; et al. Favipiravir versus arbidol for COVID-19: A randomized clinical trial. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naksuk, N.; Lazar, S.; Peeraphatdit, T.B. Cardiac safety of off-label COVID-19 drug therapy: A review and proposed monitoring protocol. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2020, 9, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescribing information for Avigan tablet 200 mg. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/File/Get/ht8jUiB_MI-aKnlwstwzvw (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- ATEA Pharmaceuticals. AT-527. Available online: https://ateapharma.com/at-527/ (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Good, S.S.; Moussa, A.; Zhou, X.J.; Pietropaolo, K.; Sommadossi, J.P. Preclinical evaluation of AT-527, a novel guanosine nucleotide prodrug with potent, pan-genotypic activity against hepatitis C virus. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berliba, E.; Bogus, M.; Vanhoutte, F.; Berghmans, P.J.; Good, S.S.; Moussa, A.; Pietropaolo, K.; Murphy, R.L.; Zhou, X.J.; Sommadossi, J.P. Safety, pharmacokinetics and antiviral activity of AT-527, a novel purine nucleotide prodrug, in HCV-infected subjects with and without cirrhosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01201-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheahan, T.P.; Sims, A.C.; Zhou, S.; Graham, R.L.; Pruijssers, A.J.; Agostini, M.L.; Leist, S.R.; Schäfer, A.; Dinnon, K.H.; Stevens, L.J.; et al. An orally bioavailable broad-spectrum antiviral inhibits SARS-CoV-2 in human airway epithelial cell cultures and multiple coronaviruses in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eabb5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toots, M.; Yoon, J.J.; Cox, R.M.; Hart, M.; Sticher, Z.M.; Makhsous, N.; Plesker, R.; Barrena, A.H.; Reddy, P.G.; Mitchell, D.G.; et al. Characterization of orally efficacious influenza drug with high resistance barrier in ferrets and human airway epithelia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaax5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, T. New Flu Antiviral Candidate May Thwart Drug Resistance. JAMA 2020, 323, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Chu, Y.; Wang, Y. HIV protease inhibitors: A review of molecular selectivity and toxicity. HIV/AIDS 2015, 7, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- AbbVie. Kaletra Prescribing Information 2020. Available online: www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/kaletratabpi.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Choy, K.-T.; Wong, A.Y.-L.; Kaewpreedee, P.; Sia, S.-F.; Chen, D.; Hui, K.P.Y.; Chu, D.K.W.; Chan, M.C.W.; Cheung, P.P.-H.; Huang, X.; et al. Remdesivir, lopinavir, emetine, and homoharringtonine inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2020, 178, 104786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Hong, A. Virtual Screening of Approved Clinic Drugs with Main Protease (3CLpro) Reveals Potential Inhibitory Effects on SARS-CoV-2. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.-J. Potential inhibitors against 2019-nCoV coronavirus M protease from clinically approved medicines. J. Genet. Genom. 2020, 47, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.M.; Cheng, V.C.; Hung, I.F.; Wong, M.M.; Chan, K.H.; Chan, K.S.; Kao, R.Y.; Poon, L.L.; Wong, C.L.; Guan, Y.; et al. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: Initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax 2004, 59, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chan, K.H.; Jiang, Y.; Kao, R.Y.; Lu, H.T.; Fan, K.W.; Cheng, V.C.; Tsui, W.H.; Hung, I.F.; Lee, T.S.; et al. In vitro susceptibility of 10 clinical isolates of SARS coronavirus to selected antiviral compounds. J. Clin. Virol. 2004, 31, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.T.; Qian, J.D.; Zhu, W.Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G.Q. A systematic review of lopinavir therapy for SARS coronavirus and MERS coronavirus-A possible reference for coronavirus disease-19 treatment option. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.F.; Yao, Y.; Yeung, M.L.; Deng, W.; Bao, L.; Jia, L.; Li, F.; Xiao, C.; Gao, H.; Yu, P.; et al. Treatment with Lopinavir/Ritonavir or Interferon-β1b Improves Outcome of MERS-CoV Infection in a Nonhuman Primate Model of Common Marmoset. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 212, 1904–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.A. Compounds with therapeutic potential against novel respiratory 2019 coronavirus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00399-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, U.J.; Won, E.J.; Kee, S.J.; Jung, S.I.; Jang, H.C. Combination therapy with lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin and interferon-α for Middle East respiratory syndrome. Antivir Ther. 2016, 21, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Jeon, S.; Shin, H.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Seong, Y.M.; Lee, W.J.; Choe, K.W.; Kang, Y.M.; Lee, B.; Park, S.J. Case of the index patient who caused tertiary transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 in Korea: The application of lopinavir/ritonavir for the treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia monitored by quantitative RT-PCR. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, B.; Wang, Y.; Wen, D.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Fan, G.; Ruan, L.; Song, B.; Cai, Y.; Wei, M.; et al. A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Li, C.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Hong, Z.; Xia, J. Arbidol combined with LPV/r versus LPV/r alone against Corona Virus Disease 2019: A retrospective cohort study. J. Infect. 2020, 81, e1–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Xu, A.; Zhang, Y.; Xuan, W.; Yan, T.; Pan, K.; Yu, W.; Zhang, J. Patients of COVID-19 may benefit from sustained Lopinavir-combined regimen and the increase of Eosinophil may predict the outcome of COVID-19 progression. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 95, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, B.E.; Ong, S.W.X.; Kalimuddin, S.; Low, J.G.; Tan, S.Y.; Loh, J.; Ng, O.-T.; Marimuthu, K.; Ang, L.W.; Mak, T.M.; et al. Epidemiologic Features and Clinical Course of Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. JAMA 2020, 323, 1488–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Tang, T.; Pang, P.; Li, M.; Ma, R.; Lu, J.; Shu, J.; You, Y.; Chen, B.; Liang, J.; et al. Treating COVID-19 with Chloroquine. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 12, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, S.; Azijn, H.; Surleraux, D.; Jochmans, D.; Tahri, A.; Pauwels, R.; Wigerinck, P.; De Béthune, M.P. TMC114, a novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor active against protease inhibitor-resistant viruses, including a broad range of clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2314–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.A.; Soule, E.E.; Davidoff, K.S.; Daniels, S.I.; Naiman, N.E.; Yarchoan, R. Activity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors against the initial autocleavage in Gag-Pol polyprotein processing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3620–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, R.; Sethumadhavan, R. Structural basis for the resilience of Darunavir (TMC114) resistance major flap mutations of HIV-1 protease. Interdiscip. Sci. 2009, 1, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Yang, R.; Yoshinaka, Y.; Amari, S.; Nakano, T.; Cinatl, J.; Rabenau, H.; Doerr, H.W.; Hunsmann, G.; Otaka, A.; et al. HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir inhibits replication of SARS-associated coronavirus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 318, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Meyer, S.; Bojkova, D.; Cinatl, J.; Van Damme, E.; Buyck, C.; Van Loock, M.; Woodfall, B.; Ciesek, S. Lack of antiviral activity of darunavir against SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 97, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Institutes of Health. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. Available online: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Dierynck, I.; Van Marck, H.; Van Ginderen, M.; Jonckers, T.H.; Nalam, M.N.; Schiffer, C.A.; Raoof, A.; Kraus, G.; Picchio, G. TMC310911, a novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor, shows in vitro an improved resistance profile and higher genetic barrier to resistance compared with current protease inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 5723–5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stellbrink, H.J.; Arastéh, K.; Schürmann, D.; Stephan, C.; Dierynck, I.; Smyej, I.; Hoetelmans, R.M.; Truyers, C.; Meyvisch, P.; Jacquemyn, B.; et al. Antiviral activity, pharmacokinetics, and safety of the HIV-1 protease inhibitor TMC310911, coadministered with ritonavir, in treatment-naive HIV-1-infected patients. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2014, 65, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Lima, C.R.; Da Silva, F.S.; Ferreira, A.C.; Mattos, M.; De Freitas, C.S.; Soares, V.C.; Dias, S.D.S.G.; Temerozo, J.R.; et al. Atazanavir, alone or in combination with ritonavir, inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication and pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, N.; Matsuyama, S.; Hoshino, T.; Yamamoto, N. Nelfinavir inhibits replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in vitro. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgio, J.F.; Alsuwat, H.S.; Al Otaibi, W.M.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Almandil, N.B.; Al Asoom, L.I.; Salahuddin, M.; Kamaraj, B.; AbdulAzeez, S. State-of-the-art tools unveil potent drug targets amongst clinically approved drugs to inhibit helicase in SARS-CoV-2. Arch. Med. Sci. 2020, 16, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Andrews, S.W.; Condroski, K.R.; Buckman, B.; Serebryany, V.; Wenglowsky, S.; Kennedy, A.L.; Madduru, M.R.; Wang, B.; Lyon, M.; et al. Discovery of danoprevir (ITMN-191/R7227), a highly selective and potent inhibitor of hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3/4A protease. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1753–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.D.; Gao, K.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Wei, G. Potentially highly potent drugs for 2019-nCoV. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.J.; Won, J.J.; Graham, R.L.; Dinnon, K.H.; Sims, A.C.; Feng, J.Y.; Cihlar, T.; Denison, M.R.; Baric, R.S.; Sheahan, T.P. Broad spectrum antiviral remdesivir inhibits human endemic and zoonotic deltacoronaviruses with a highly divergent RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Antiviral Res. 2019, 169, 104541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Huang, Z.; Gong, F.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, J.J. First Clinical Study Using HCV Protease Inhibitor Danoprevir to Treat Naive and Experienced COVID-19 Patients. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, R.D.; Novak, R.M. Reviews of anti-infective agents: Maraviroc: The first of a new class of antiretroviral agents. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 47, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsi, A.; Mohammad, T.; Anwar, S.; Alajmi, M.F.; Hussain, A.; Rehman, M.T.; Islam, A.; Hassan, M.I. Glecaprevir and Maraviroc are high-affinity inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease: Possible implication in COVID-19 therapy. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20201256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, A.O.; Severson, W.; Jonsson, C.; Singh, K.; Weiss, S.R.; Sarafianos, S.G. Novel inhibitors of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry that act by three distinct mechanisms. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 8017–8028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, Y.Y. Selinexor: First Global Approval. Drugs 2019, 79, 1485–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podar, K.; Shah, J.; Chari, A.; Richardson, P.G.; Jagannath, S. Selinexor for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2020, 21, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, A.; Vogl, D.T.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Nooka, A.K.; Yee, A.J.; Huff, C.A.; Moreau, P.; Dingli, D.; Cole, C.; Lonial, S.; et al. Oral selinexor-dexamethasone for triple-class refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widman, D.G.; Gornisiewicz, S.; Shacham, S.; Tamir, S. In vitro toxicity and efficacy of verdinexor, an exportin 1 inhibitor, on opportunistic viruses affecting immunocompromised individuals. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, C.; Ghildyal, R. CRM1 inhibitors for antiviral therapy. Front Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.E.; Jang, G.M.; Bouhaddou, M.; Xu, J.; Obernier, K.; O’Meara, M.J.; Guo, J.Z.; Swaney, D.L.; Tummino, T.A.; Hüttenhain, R.; et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundt, E.C.; Yu, L.; Park, E.; Lenardo, M.J.; Xu, X.N. Molecular determinants for subcellular localization of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus open reading frame 3b protein. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 6631–6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.; Åkerström, S.; Sharma, A.K.; Chow, V.T.; Teow, S.; Abrenica, B.; Booth, S.A.; Booth, T.F.; Mirazimi, A.; Lal, S.K. SARS-CoV 9b protein diffuses into nucleus, undergoes active Crm1 mediated nucleocytoplasmic export and triggers apoptosis when retained in the nucleus. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, R.; Van Zyl, M.; Fielding, B.C. The coronavirus nucleocapsid is a multifunctional protein. Viruses 2014, 6, 2991–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ujike, M.; Huang, C.; Shirato, K.; Matsuyama, S.; Makino, S.; Taguchi, F. Two palmitylated cysteine residues of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike (S) protein are critical for S incorporation into virus-like particles, but not for M-S co-localization. J. Gen. Virol. 2012, 93, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, A.C.; Tilton, S.C.; Menachery, V.D.; Gralinski, L.E.; Schäfer, A.; Matzke, M.M.; Webb-Robertson, B.J.; Chang, J.; Luna, M.L.; Long, C.E.; et al. Release of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nuclear import block enhances host transcription in human lung cells. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 3885–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajiri, N.; De La Peña, I.; Acosta, S.A.; Kaneko, Y.; Tamir, S.; Landesman, Y.; Carlson, R.; Shacham, S.; Borlongan, C.V. A Nuclear Attack on Traumatic Brain Injury: Sequestration of Cell Death in the Nucleus. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016, 22, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perwitasari, O.; Johnson, S.; Yan, X.; Howerth, E.; Shacham, S.; Landesman, Y.; Baloglu, E.; McCauley, D.; Tamir, S.; Tompkins, S.M.; et al. Verdinexor, a novel selective inhibitor of nuclear export, reduces influenza a virus replication in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 10228–10243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Gui, H.; Feng, Z.; Xu, H.; Li, G.; Li, M.; Chen, T.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Bai, Z.; et al. KPT-330, a potent and selective CRM1 inhibitor, exhibits anti-inflammation effects and protection against sepsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, V.R.; Curran, M.P. Nitazoxanide: A review of its use in the treatment of gastrointestinal infections. Drugs 2007, 67, 1947–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, A.; Bhat, H.R.; Ghosh, S.K. Update on Nitazoxanide: A Multifunctional Chemotherapeutic Agent. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2018, 15, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, J.F. Nitazoxanide: A first-in-class broad-spectrum antiviral agent. Antiviral Res. 2014, 110, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossignol, J.F. Nitazoxanide, a new drug candidate for the treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Infect. Public Health 2016, 9, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisson, G.; Goodwin, A.; Raudonikiene, A.; Hughes, N.J.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K.; Berg, D.E.; Hoffman, P.S. Enzymes associated with reductive activation and action of nitazoxanide, nitrofurans, and metronidazole in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossignol, J.F.; La Frazia, S.; Chiappa, L.; Ciucci, A.; Santoro, M.G. Thiazolides, a new class of anti-influenza molecules targeting viral hemagglutinin at post-translational level. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 29798–29808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Forrest, J.C.; Zhang, X. A screen of the NIH collection small molecule library identifies potential coronavirus. Antiviral Res. 2015, 114, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacentini, S.; La Frazia, S.; Riccio, A.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Topai, A.; Nicolotti, O.; Rossignol, J.-F.; Santoro, M.G. Nitazoxanide inhibits paramyxovirus replication by targeting the Fusion protein folding: Role of glycoprotein-specific thiol oxidoreductase ERp57. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, K.; Labitzke, K.; Liu, B.; Wang, P.; Henckels, K.; Gaida, K.; Elliott, R.; Chen, J.J.; Liu, L.; Leith, A.; et al. Drug repurposing: The anthelmintics niclosamide and nitazoxanide are potent TMEM16A antagonists that fully bronchodilate airways. Front Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, S. The Pharmacology of Indomethacin. Headache 2016, 56, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amici, C.; Di Caro, A.; Ciucci, A.; Chiappa, L.; Castilletti, C.; Martella, V.; Decaro, N.; Buonavoglia, C.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Santoro, M.G. Indomethacin has a potent antiviral activity against SARS coronavirus. Antivir. Ther. 2006, 11, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Gao, X.; Wu, Z.; Selinger, D.W.; Zhou, Z. Indomethacin has a potent antiviral activity against SARS CoV-2 in vitro and canine coronavirus in vivo. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amici, C.; La Frazia, S.; Brunelli, C.; Balsamo, M.; Angelini, M.; Santoro, M.G. Inhibition of viral protein translation by indomethacin in vesicular stomatitis virus infection: Role of eIF2α kinase PKR. Cell Microbiol. 2015, 17, 1391–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossen, J.W.; Bouma, J.; Raatgeep, R.H.; Büller, H.A.; Einerhand, A.W. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase activity reduces rotavirus infection at a postbinding step. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 9721–9730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.Y.; Liu, B.H.; Zhao, D.Y.; Cheng, G.F. Effect of indomethacin on expression of interleukin-6 caused by lipopolysaccharide in rheumatoid arthritic patients’ synoviocyte. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2003, 38, 809–812. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, P.A.; Clissold, S.P. Naproxen. A reappraisal of its pharmacology, and therapeutic use in rheumatic diseases and pain states. Drugs 1990, 40, 91–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearney, P.M.; Baigent, C.; Godwin, J.; Halls, H.; Emberson, J.R.; Patrono, C. Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2006, 332, 1302–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Fan, W.; Zhang, S.; Jiao, P.; Shang, Y.; Cui, L.; Mahesutihan, M.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Gao, G.F.; et al. Naproxen Exhibits Broad Anti-influenza Virus Activity in Mice by Impeding Viral Nucleoprotein Nuclear Export. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebell, M.H. In Hospitalized Patients with Influenza and an Infiltrate, Adding Clarithromycin and Naproxen to Oseltamivir Improves Outcomes. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 96. Online. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pan, T.; Peng, Z.; Tan, L.; Zou, F.; Zhou, N.; Liu, B.; Liang, L.; Chen, C.; Liu, J.; Wu, L.; et al. Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs Potently Inhibit the Replication of Zika Viruses by Inducing the Degradation of AXL. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01018-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrier, O.; Dilly, S.; Pizzorno, A.; Henri, J.; Berenbaum, F.; Lina, B.; Fève, B.; Adnet, F.; Sabbah, M.; Rosa-Calatrava, M.; et al. Broad-spectrum antiviral activity of naproxen: From Influenza A to SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immunic Therapeutics. IMU-838. Available online: https://www.immunic-therapeutics.com/imu838/ (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Muehler, A.; Peelen, E.; Kohlhof, H.; Gröppel, M.; Vitt, D. Vidofludimus calcium, a next generation DHODH inhibitor for the Treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 43, 102129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehler, A.; Kohlhof, H.; Groeppel, M.; Vitt, D. Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of Vidofludimus calcium (IMU-838) After Single and Multiple Ascending Oral Doses in Healthy Male Subjects. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2020, 45, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Immunic Therapeutics. Immunic, Inc. Reports that IMU-838, a Selective Oral DHODH Inhibitor, Has Demonstrated Preclinical Activity Against SARS-CoV-2 and Explores Plans for a Phase 2 Clinical Trial in COVID-19 Patients. Available online: https://www.immunic-therapeutics.com/2020/04/21/immunic-inc-reports-that-imu-838-a-selective-oral-dhodh-inhibitor-has-demonstrated-preclinical-activity-against-sars-cov-2-and-explores-plans-for-a-phase-2-clinical-trial-in-covid-19-patients/ (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Peters, G.J. Re-evaluation of Brequinar sodium, a dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2018, 37, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, V.K.; Ghate, M. Recent developments in the medicinal chemistry and therapeutic potential of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) inhibitors. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 1039–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madak, J.T.; Bankhead, A.; Cuthbertson, C.R.; Showalter, H.D.; Neamati, N. Revisiting the role of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase as a therapeutic target for cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 195, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boschi, D.; Pippione, A.C.; Sainas, S.; Lolli, M.L. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors in anti-infective drug research. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 183, 111681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.G.; Ávila-Pérez, G.; Nogales, A.; Blanco-Lobo, P.; De La Torre, J.C.; Martínez-Sobrido, L. Identification and Characterization of Novel Compounds with Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Activity against Influenza A and B Viruses. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e02149-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.I.; Krpina, K.; Ianevski, A.; Shtaida, N.; Jo, E.; Yang, J.; Koit, S.; Tenson, T.; Hukkanen, V.; Anthonsen, M.W.; et al. Novel Antiviral Activities of Obatoclax, Emetine, Niclosamide, Brequinar, and Homoharringtonine. Viruses 2019, 11, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.F.; Gong, M.J.; Sun, Y.F.; Shao, J.J.; Zhang, Y.G.; Chang, H.Y. Antiviral activity of brequinar against foot-and-mouth disease virus infection in vitro and in vivo. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 116, 108982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Ding, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Shang, W.; Jiang, X.; et al. Novel and potent inhibitors targeting DHODH, a rate-limiting enzyme in de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis, are broad-spectrum antiviral against RNA viruses including newly emerged coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langtry, H.D.; Grant, S.M.; Goa, K.L. Famotidine. An updated review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in peptic ulcer disease and other allied diseases. Drugs 1989, 38, 551–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedberg, D.E.; Conigliaro, J.; Wang, T.C.; Tracey, K.J.; Callahan, M.V.; Abrams, J.A.; Sobieszczyk, M.E.; Markowitz, D.D.; Gupta, A.; O’Donnell, M.R.; et al. Famotidine Use is Associated with Improved Clinical Outcomes in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: A Propensity Score Matched Retrospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1129–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janowitz, T.; Gablenz, E.; Pattinson, D.; Wang, T.C.; Conigliaro, J.; Tracey, K.; Tuveson, D. Famotidine use and quantitative symptom tracking for COVID-19 in non-hospitalised patients: A case series. Gut 2020, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhong, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, M.; Li, X.; et al. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 766–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Arnst, K.E.; Wang, Y.; Kumar, G.; Ma, D.; Chen, H.; Wu, Z.; Yang, J.; White, S.W.; Miller, D.D.; et al. Structural modification of the 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl moiety in the tubulin inhibitor VERU-111 leads to improved antiproliferative activities. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 7877–7891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veru Inc. VERU-111. Available online: https://verupharma.com/pipeline/veru-111/ (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Deftereos, S.G.; Giannopoulos, G.; Vrachatis, D.A.; Siasos, G.D.; Giotaki, S.G.; Gargalianos, P.; Metallidis, S.; Sianos, G.; Baltagiannis, S.; Panagopoulos, P.; et al. Effect of Colchicine vs Standard Care on Cardiac and Inflammatory Biomarkers and Clinical Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized With Coronavirus Disease 2019: The GRECCO-19 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 3, e2013136. [Google Scholar]

- Li, E.K.; Tam, L.S.; Tomlinson, B. Leflunomide in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Ther. 2004, 26, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breedveld, F.C.; Dayer, J.M. Leflunomide: Mode of action in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2000, 59, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, M.L.; Schleyerbach, R.; Kirschbaum, B.J. Leflunomide: An immunomodulatory drug for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. Immunopharmacology 2000, 47, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhoff, E.; Tylden, G.D.; Kjerpeseth, L.J.; Gutteberg, T.J.; Hirsch, H.H.; Rinaldo, C.H. Leflunomide inhibition of BK virus replication in renal tubular epithelial cells. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 2150–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, R.K.; Mossad, S.B.; Poggio, E.; Lard, M.; Budev, M.; Bolwell, B.; Waldman, W.J.; Braun, W.; Mawhorter, S.D.; Fatica, R.; et al. Utility of leflunomide in the treatment of complex cytomegalovirus syndromes. Transplantation 2010, 90, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschner, S.; Burst, V. Leflunomide: A drug with a potential beyond rheumatology. Immunotherapy 2010, 2, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, R.I.; Herrmann, M.L.; Frangou, C.G.; Wahl, G.M.; Morris, R.E.; Strand, V.; Kirschbaum, B.J. Mechanism of action for leflunomide in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Immunol. 1999, 93, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehgal, S.N. Sirolimus: Its discovery, biological properties, and mechanism of action. Transplant Proc. 2003, 35, 7S–14S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirken, R.A.; Wang, Y.L. Molecular actions of sirolimus: Sirolimus and mTor. Transplant Proc. 2003, 35, 227S–230S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohr, S.; Costa, R.; Sandmann, L.; Westhaus, S.; Pfaender, S.; Anggakusuma; Dazert, E.; Meuleman, P.; Vondran, F.W.R.; Manns, M.P.; et al. Host cell mTORC1 is required for HCV RNA replication. Gut 2016, 65, 2017–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindrachuk, J.; Ork, B.; Hart, B.J.; Mazur, S.; Holbrook, M.R.; Frieman, M.B.; Traynor, D.; Johnson, R.F.; Dyall, J.; Kuhn, J.H.; et al. Antiviral potential of ERK/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling modulation for middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection as identified by tem-poral kinome analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 1088–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hou, Y.; Shen, J.; Huang, Y.; Martin, W.; Cheng, F. Network-based drug repurposing for novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Chung, F.T.; Lin, S.M.; Huang, S.Y.; Chou, C.L.; Lee, K.Y.; Lin, T.Y.; Kuo, H.P. Adjuvant treatment with a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, sirolimus, and steroids improves outcomes in patients with severe H1N1 pneumonia and acute respiratory failure. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, G.M.; Newman, D.J. Marine natural products and related compounds in clinical and advanced preclinical trials. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 1216–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, N.G.M.; Valentão, P.; Andrade, P.B.; Pereira, R.B. Plitidepsin to treat multiple myeloma. Drugs Today (Barc.) 2020, 56, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PharmMar. PharmaMar Reports Positive Results for Aplidin® against Coronavirus HCoV-229E. Available online: http://pharmamar.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/PR_Results_Aplidin_coronavirus.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Sasikumar, A.N.; Perez, W.B.; Kinzy, T.G. The many roles of the eukaryotic elongation factor 1 complex. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. 2012, 3, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wei, T.; Abbott, C.M.; Harrich, D. The unexpected roles of eukaryotic translation elongation factors in RNA virus replication and pathogenesis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013, 77, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsythe, P.; Paterson, S. Ciclosporin 10 years on: Indications and efficacy. Vet. Rec. 2014, 174, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapturczak, M.H.; Meier-Kriesche, H.U.; Kaplan, B. Pharmacology of calcineurin antagonists. Transplant Proc. 2004, 36, 25S–32S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, G.; Graveley, R.; Seid, J.; Al-Humidan, A.K.; Skjodt, H. Mechanisms of action of cyclosporine and effects on connective tissues. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1992, 21, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulds, D.; Goa, K.L.; Benfield, P. Cyclosporin. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in immunoregulatory disorders. Drugs 1993, 45, 953–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information for Neoral®. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/050715s027,050716s028lbl.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- De Wilde, A.H.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; Van der Meer, Y.; Thiel, V.; Narayanan, K.; Makino, S.; Snijder, E.J.; Van Hemert, M.J. Cyclosporin A inhibits the replication of diverse coronaviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 2542–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Serradilla, M.; Risco, C.; Pacheco, B. Drug repurposing for new, efficient, broad spectrum antivirals. Virus Res. 2019, 264, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianevski, A.; Zusinaite, E.; Kuivanen, S.; Strand, M.; Lysvand, H.; Teppor, M.; Kakkola, L.; Paavilainen, H.; Laajala, M.; Kallio-Kokko, H.; et al. Novel activities of safe-in-human broad-spectrum antiviral agents. Antiviral Res. 2018, 154, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cour, M.; Ovize, M.; Argaud, L. Cyclosporine A: A valid candidate to treat COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory failure? Crit. Care 2020, 24, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lernia, V. Antipsoriatic treatments during COVID-19 outbreak. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobarra, N.; Shanaki, M.; Ehteram, H.; Nasiri, H.; Sahmani, M.; Saeidi, M.; Goudarzi, M.; Pourkarim, H.; Azad, M. A Review on Iron Chelators in Treatment of Iron Overload Syndromes. Int. J. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Res. 2016, 10, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allain, P.; Mauras, Y.; Chaleil, D.; Simon, P.; Ang, K.S.; Cam, G.; Le Mignon, L.; Simon, M. Pharmacokinetics and renal elimination of desferrioxamine and ferrioxamine in healthy subjects and patients with haemochromatosis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1987, 24, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bataille, S.; Pedinielli, N.; Bergounioux, J.P. Could ferritin help the screening for COVID-19 in hemodialysis patients? Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 235–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drakesmith, H.; Prentice, A. Viral infection and iron metabolism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moalem, S.; Weinberg, E.D.; Percy, M.E. Hemochromatosis and the enigma of misplaced iron: Implications for infectious disease and survival. Biometals 2004, 17, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessling-Resnick, M. Iron homeostasis and the inflammatory response. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2010, 30, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Kim, R.Y.; Brown, A.C.; Donovan, C.; Vanka, K.S.; Mayall, J.R.; Liu, G.; Pillar, A.L.; Jones-Freeman, B.; Xenaki, D.; et al. Critical role for iron accumulation in the pathogenesis of fibrotic lung disease. J. Pathol. 2020, 251, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalamaga, M.; Karampela, I.; Mantzoros, C.S. Commentary: Could Iron Chelators Prove to Be Useful as an Adjunct to COVID-19 Treatment Regimens? Metabolism 2020, 108, 154260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Meyer, D. Desferrioxamine as immunomodulatory agent during microorganism infection. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, N.A.; Van Der Bruggen, T.; Oudshoorn, M.; Nottet, H.S.; Marx, J.J.; Van Asbeck, B.S. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in human mononuclear blood cells by the iron chelators deferoxamine, deferiprone, and bleomycin. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 181, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolomei, G.; Cevik, R.E.; Marcello, A. Modulation of hepatitis C virus replication by iron and hepcidin in Huh7 hepatocytes. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 2072–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theurl, I.; Zoller, H.; Obrist, P.; Datz, C.; Bachmann, F.; Elliott, R.M.; Weiss, G. Iron regulates hepatitis C virus translation via stimulation of expression of translation initiation factor 3. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 190, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchemin, J.; Paradkar, P.N. Iron availability affects West Nile virus infection in its mosquito vector. J. Virol. 2017, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren, F.; Verkerk, M.S.; Van Der Bruggen, T.; Marx, J.J.; Van Asbeck, B.S.; Diepersloot, R.J. Iron chelation and hydroxyl radical scavenging reduce the inflammatory response of endothelial cells after infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae or influenza A. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 32, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artymowicz, R.J.; James, V.E. Atovaquone: A new antipneumocystis agent. Clin. Pharm. 1993, 12, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, L.G.; Flaherty, J.F. Atovaquone: A review. Ann. Pharmacother. 1993, 27, 1488–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behbahani, R.; Moshfeghi, M.; Baxter, J.D. Therapeutic approaches for AIDS-related Toxoplasmosis. Ann. Pharmacother. 1995, 29, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, M.; Salazar, J.C.; Leopold, H.; Krause, P.J. Atovaquone and azithromycin for the treatment of babesiosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 1454–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C.M.; Goa, K.L. Atovaquone. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in opportunistic infections. Drugs 1995, 50, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggish, A.L.; Hill, D.R. Antiparasitic agent atovaquone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farag, A.; Wang, P.; Ahmed, M.; Sadek, H. Identification of FDA approved drugs targeting COVID-19 virus by structure-based drug repositioning. ChemRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, M.; Stefanovic, D.; Pejnovic, N. Comparative study of the clinical efficacy of four DMARDs (leflunomide, methotrexate, cyclosporine, and levamisole) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Transplant Proc. 1998, 30, 4135–4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sany, J. Immunological treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 1990, 8, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olsen, N.; Halberg, P.; Halskov, O.; Bentzon, M.W. Scintimetric assessment of synovitis activity during treatment with disease modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann. Rheumatol. Dis. 1988, 47, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, J.A.; Lavonas, E.J. Agranulocytosis and other consequences due to use of illicit cocaine contaminated with levamisole. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2012, 19, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.J.; Verma, S.; Levandoski, M. Drug resistance and neurotransmitter receptors of nematodes: Recent studies on the mode of action of levamisole. Parasitology 2005, 131, S71–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, O.; Moulder, J.K.; Grandin, L.; Somers, M.J. Short- and long-term efficacy of levamisole as adjunctive therapy in childhood nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2008, 23, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, R.; Amit, D.; Prashar, V.; Mukesh, K. Potential inhibitors against papain-like protease of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) from FDA approved drugs. ChemRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.; Ladizinski, B.; Federman, D.G. Complications associated with use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine: An emerging public health challenge. Mayo. Clin. Proc. 2012, 87, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renoux, G. The general immunopharmacology of levamisole. Drugs 1980, 20, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunbiyi, P.O.; Conlon, P.D.; Black, W.D.; Eyre, P. Levamisole-induced attenuation of alveolar macrophage dysfunction in respiratory virus-infected calves. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1988, 10, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, D.L.; Hubbard, V.D.; Burton, J.; Smee, D.F.; Morrey, J.D.; Otto, M.J.; Sidwell, R.W. Inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARSCoV) by calpain inhibitors and beta-D-N4-hydroxycytidine. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2004, 15, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; Ackermann, K.; Stuart, M.; Wex, C.; Protzer, U.; Schätzl, H.M.; Gilch, S. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Replication Is Severely Impaired by MG132 due to Proteasome-Independent Inhibition of M-Calpain. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 10112–10122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blade Therapeutics. Available online: https://www.blademed.com/science/ (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Heard, K. Acetylcysteine for Acetaminophen Poisoning. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiler, J.; Michaelis, M.; Naczk, P.; Leutz, A.; Langer, K.; Doerr, H.-W.; Cinatl, J., Jr. N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) inhibits virus replication and expression of pro-inflammatory molecules in A549 cells infected with highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza A virus. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 79, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezzi, P.; Ungheri, D. Synergistic Combination of N-Acetylcysteine and Ribavirin to Protect from Lethal Influenza Viral Infection in a Mouse Model. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2004, 17, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Flora, S.; Grassi, C.; Carati, L. Attenuation of influenza-like symptomatology and improvement of cell-mediated immunity with long-term N-acetylcysteine treatment. Eur. Respir. J. 1997, 10, 1535–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitkreutz, R.; Pittack, N.; Nebe, C.T.; Schuster, D.; Brust, J.; Beichert, M.; Hack, V.; Daniel, V.; Edler, L.; Droge, W. Improvement of immune functions in HIV infection by sulfur supplementation: Two randomized trials. J. Mol. Med. 2000, 78, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska, A.; Verbraecken, J.; Darquennes, K.; De Backer, W.A. Role of N-acetylcysteine in the management of COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2006, 1, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska, A.; Manuel-Y-Keenoy, B.; De Backer, W. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory efficacy of NAC in the treatment of COPD: Discordant in vitro and in vivo dose-effects: A review. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 20, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medici, T.C.; Radielovic, P. Effects of Drugs on Mucus Glycoproteins and Water in Bronchial Secretion. J. Int. Med. Res. 1979, 7, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- eskey, G.; Abrahem, R.; Cao, R.; Gyurjian, K.; Islamoglu, H.; Lucero, M.; Martinez, A.; Paredes, E.; Salaiz, O.; Robinson, B.; et al. Glutathione as a Marker for Human Disease. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 87, 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.H.; Kang, S.-S.; Kim, J.Y.; Tchah, H. The Antioxidant N-Acetylcysteine Inhibits Inflammatory and Apoptotic Processes in Human Conjunctival Epithelial Cells in a High-Glucose Environment. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Ju, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, T. N-acetylcysteine improves oxidative stress and inflammatory response in patients with community acquired pneumonia. Medicine 2018, 97, e13087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, H.-Q.; Guo, H.-Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Hua, S.-N.; Yu, J.; Xiao, P.-G.; et al. Identification of natural compounds with antiviral activities against SARS-associated coronavirus. Antivir. Res. 2005, 67, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.-Y.; Lee, G.E.; Park, H.; Cho, J.; Kim, Y.-E.; Lee, J.-Y.; Ju, C.; Kim, W.-K.; Kim, J.I.; Park, M.-S. Pyronaridine and artesunate are potential antiviral drugs against COVID-19 and influenza. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendrot, M.; Duflot, I.; Boxberger, M.; Delandre, O.; Jardot, P.; Le Bideau, M.; Andreani, J.; Fonta, I.; Mosnier, J.; Rolland, C.; et al. Antimalarial artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACT) and COVID-19 in Africa: In vitro inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication by mefloquine-artesunate. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, S1201-9712, 30661–30665. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, R.; Hu, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, W.; et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Potential of Artemisinins In Vitro. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 2524–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluck, U.; Martin, U.; Bosse, B.; Reimer, K.; Mueller, S. A Clinical Study on the Tolerability of a Liposomal Povidone-Iodine Nasal Spray: Implications for Further Development. ORL 2006, 69, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ggers, M.; Koburger-Janssen, T.; Eickmann, M.; Zorn, J. In Vitro Bactericidal and Virucidal Efficacy of Povidone-Iodine Gargle/Mouthwash against Respiratory and Oral Tract Pathogens. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2018, 7, 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- The FDA Approved Drug Products: Peridex (Chlorhexidine Gluconate) Oral Rinse. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/019028s020lbl.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Lim, K.S.; Kam, P.C. Chlorhexidine-pharmacology and clinical applications. Anaesth Intensive Care 2008, 36, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, Z.; Abbott, P.V. The properties and applications of chlorhexidine in endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2009, 42, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karpiński, T.M.; Szkaradkiewicz, A.K. Chlorhexidine-pharmaco-biological activity and application. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Oz, M.; Lorke, D.E.; Hasan, M.; Petroianu, G.A. ChemInform Abstract: Cellular and Molecular Actions of Methylene Blue in the Nervous System. Chemin 2011, 42, 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.; Yan, Y.; Wang, L. Coronavirus Disease 2019: Coronaviruses and Blood Safety. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2020, 34, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd, R.A.; Schneider, J.; Dittmer, D.P. Methylene blue photoinactivation of RNA viruses. Antivir. Res. 2004, 61, 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, C.; Yu, B.; Zhang, J.; Wu, H.; Zhou, X.; Yao, H.; Liu, F.; Lu, X.; Cheng, L.; Jiang, M.; et al. Methylene blue photochemical treatment as a reliable SARS-CoV-2 plasma virus inactivation method for blood safety and convalescent plasma therapy for the COVID-19 outbreak. Res. Square 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickmann, M.; Gravemann, U.; Handke, W.; Tolksdorf, F.; Reichenberg, S.; Müller, T.H.; Seltsam, A. Inactivation of three emerging viruses—Severe acute respiratory syndrome corona- virus, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus and Nipah virus—In platelet concentrates by ultraviolet C light and in plasma by methylene blue plus visible light. Vox Sang 2020, 115, 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Eickmann, M.; Gravemann, U.; Handke, W.; Tolksdorf, F.; Reichenberg, S.; Müller, T.H.; Seltsam, A. Inactivation of Ebola virus and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in platelet concentrates and plasma by ultraviolet C light and methylene blue plus visible light, respectively. Transfusion 2018, 58, 2202–2207. [Google Scholar]

- Papin, J.F.; Floyd, R.A.; Dittmer, D.P. Methylene blue photoinactivation abolishes West Nile virus infectivity in vivo. Antivir. Res. 2005, 68, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginimuge, P.R.; Jyothi, S.D. Methylene blue: Revisited. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 26, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Preiser, J.-C.; Lejeune, P.; Roman, A.; Carlier, E.; De Backer, D.; Leeman, M.; Kahn, R.; Vincent, J.-L. Methylene blue administration in septic shock: A clinical trial. Crit. Care Med. 1995, 23, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, E.S.H.; Howes, D. Use of Methylene Blue in Sepsis: A Systematic Review. J. Intensiv. Care Med. 2006, 21, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.-H.; Wang, S.-Y.; Chen, L.-L.; Zhuang, J.-Y.; Ke, Q.-F.; Xiao, D.-R.; Lin, W.-P. Methylene Blue Mitigates Acute Neuroinflammation after Spinal Cord Injury through Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Microglia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, H.; Beland, J.L.; Del-Pan, N.C.; Kobzik, L.; Brewer, J.P.; Martin, T.R.; Rimm, I.J. Suppression of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 (HSV-1)–induced Pneumonia in Mice by Inhibition of Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS, NOS2). J. Exp. Med. 1997, 185, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, T.E.; Paoletti, A.D.; Buchmeier, M.J. Disassociation between the in vitro and in vivo effects of nitric oxide on a neurotropic murine coronavirus. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 2202–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, M.; Marsden, P.A.; Cole, E.; Sloan, S.; Fung, L.S.; Ning, Q.; Ding, J.W.; Leibowitz, J.L.; Phillips, M.J.; Levy, G.A. Resistance to Murine Hepatitis Virus Strain 3 Is Dependent on Production of Nitric Oxide. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 7084–7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerström, S.; Mousavi-Jazi, M.; Klingström, J.; Leijon, M.; Lundkvist, A.; Mirazimi, A. Nitric Oxide Inhibits the Replication Cycle of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 1966–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Åkerström, S.; Gunalan, V.; Keng, C.T.; Tan, Y.-J.; Mirazimi, A. Dual effect of nitric oxide on SARS-CoV replication: Viral RNA production and palmitoylation of the S protein are affected. Virology 2009, 395, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colasanti, M.; Persichini, T.; Venturini, G.; Ascenzi, P. S-nitrosylation of viral proteins: Molecular bases for antiviral effect of nitric oxide. IUBMB Life 1999, 48, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, J.; Murata, I. Nitric oxide inhalation as an interventional rescue therapy for COVID-19-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2020, 10, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Liu, P.; Gao, H.; Sun, B.; Chao, D.; Wang, F.; Zhu, Y.; Hedenstierna, G.; Wang, C.G. Inhalation of Nitric Oxide in the Treatment of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome: A Rescue Trial in Beijing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 39, 1531–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamanian, R.T.; Pollack, C.V., Jr.; Gentile, M.A.; Rashid, M.; Fox, J.C.; Mahaffey, K.W.; de Jesus Perez, V. Outpatient Inhaled Nitric Oxide in a Patient with Vasoreactive Idiopathic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and COVID-19 Infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinella, M.A. Indomethacin and resveratrol as potential treatment adjuncts for SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 74, e13535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The National Library of Medicine. Pubchem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/445154 (accessed on 9 July 2020).

- Campagna, M.; Rivas, C. Antiviral activity of resveratrol. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010, 38, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-C.; Ho, C.-T.; Chuo, W.-H.; Li, S.; Wang, T.T.; Lin, C.-C. Effective inhibition of MERS-CoV infection by resveratrol. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xu, J.; Song, X.; Jia, R.; Yin, Z.-Q.; Cheng, A.; Jia, R.; Zou, Y.; Li, L.; Yin, L.; et al. Antiviral effect of resveratrol in ducklings infected with virulent duck enteritis virus. Antivir. Res. 2016, 130, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cui, Q.; Fu, Q.; Song, X.; Jia, R.; Yang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Li, L.; He, C.; Liang, X.; et al. Antiviral properties of resveratrol against pseudorabies virus are associated with the inhibition of IkB kinase activation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8772. [Google Scholar]

- Debiaggi, M.; Tateo, F.; Pagani, L.; Luini, M.; Romero, E. Effects of propolis flavonoids on virus infectivity and replication. Microbiologica 1990, 13, 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- De Palma, A.M.; Vliegen, I.; De Clercq, E.; Neyts, J. Selective inhibitors of picornavirus replication. Med. Res. Rev. 2008, 28, 823–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishitsuka, H.; Ohsawa, C.; Ohiwa, T.; Umeda, I.; Suhara, Y. Antipicornavirus flavone Ro 09-0179. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1982, 22, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaul, T.N.; Middleton, E.; Ogra, P.L. Antiviral effect of flavonoids on human viruses. J. Med. Virol. 1985, 15, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, D.L.; Chao, C.-F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huong, S.-M.; Huang, E.-S. Human cytomegalovirus-inhibitory flavonoids: Studies on antiviral activity and mechanism of action. Antivir. Res. 2005, 68, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandi, K.; Teoh, B.-T.; Sam, S.-S.; Wong, P.F.; Mustafa, M.R.; Abubakar, S. Antiviral activity of four types of bioflavonoid against dengue virus type-2. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biancatelli, R.M.L.C.; Berrill, M.; Catravas, J.D.; Marik, P.E. Quercetin and Vitamin C: An Experimental, Synergistic Therapy for the Prevention and Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 Related Disease (COVID-19). Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, M.-S.; Shin, D.H. Flavonoids with inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020, 35, 1539–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garaci, E. Thymosin 1: A Historical Overview. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1112, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerini, R.; Garaci, E. Historical review of thymosin ? 1 in infectious diseases. Expert Opin. Boil. Ther. 2015, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramenzi, A.; Cursaro, C.; Andreone, P.; Bernardi, M. Thymalfasin: Clinical pharmacology and antiviral applications. BioDrugs 1998, 9, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SciClone Pharmaceuticals. Available online: http://www.shijiebiaopin.net/upload/product/2011121219115812.PDF (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Actor, J.K.; Hwang, S.-A.; Kruzel, M.L. Lactoferrin as a natural immune modulator. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 1956–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutone, A.; Rosa, L.; Ianiro, G.; Lepanto, M.S.; Di Patti, M.C.B.; Valenti, P.; Musci, G. Lactoferrin’s Anti-Cancer Properties: Safety, Selectivity, and Wide Range of Action. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutone, A.; Lepanto, M.S.; Rosa, L.; Scotti, M.J.; Rossi, A.; Ranucci, S.; De Fino, I.; Bragonzi, A.; Valenti, P.; Musci, G.; et al. Aerosolized Bovine Lactoferrin Counteracts Infection, Inflammation and Iron Dysbalance in A Cystic Fibrosis Mouse Model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Chronic Lung Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoni, P.; Meyer, M.; Stolfi, I.; Rinaldi, M.; Cattani, S.; Pugni, L.; Romeo, M.G.; Messner, H.; Decembrino, L.; Laforgia, N.; et al. Bovine lactoferrin supplementation for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in very-low-birth-weight neonates: A randomized clinical trial. Early Hum. Dev. 2014, 90, S60–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlutti, F.; Pantanella, F.; Natalizi, T.; Frioni, A.; Paesano, R.; Polimeni, A.; Valenti, P. Antiviral Properties of Lactoferrin—A Natural Immunity Molecule. Molecules 2011, 16, 6992–7018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Strate, B.; Beljaars, L.; Molema, G.; Harmsen, M.; Meijer, D. Antiviral activities of lactoferrin. Antivir. Res. 2001, 52, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Yang, N.; Deng, J.; Liu, K.; Yang, P.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, C. Inhibition of SARS Pseudovirus Cell Entry by Lactoferrin Binding to Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peroni, D.G.; Fanos, V. Lactoferrin is an important factor when breastfeeding and COVID-19 are considered. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Fu, D.; Ren, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, D.; Zhang, F.; Xia, X.; Lv, T. Treatment with convalescent plasma for COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallard, E.; Lescure, F.-X.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Mentre, F.; Peiffer-Smadja, N.; Ader, F.; Bouadma, L.; Poissy, J.; Timsit, J.-F.; Lina, B.; et al. Type 1 interferons as a potential treatment against COVID-19. Antivir. Res. 2020, 178, 104791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi-Monfared, E.; Rahmani, H.; Khalili, H.; Hajiabdolbaghi, M.; Salehi, M.; Abbasian, L.; Kazemzadeh, H.; Yekaninejad, M.S. A Randomized Clinical Trial of the Efficacy and Safety of Interferon β-1a in Treatment of Severe COVID-19. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01061-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldanha-Araujo, F.; Garcez, E.M.; Silva-Carvalho, A.E.; Carvalho, J.L. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A New Piece in the Puzzle of COVID-19 Treatment. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Viral Polymerase Inhibitors | |

| Remdesivir | Emtricitabine & tenofovir alafenamide |

| Galidesivir | Favipiravir |

| Ribavirin | AT-527 |

| Clevudine | EIDD-2801 |

| Emtricitabine & tenofovir disoproxil | |

| Viral protease inhibitors | |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | Atazanavir |

| Darunavir/cobicistat | Danoprevir/ritonavir |

| ASC-09 | Maraviroc |

| Miscellaneous antiviral agents | |

| Selinexor | Levamisole |

| Nitazoxanide | BLD-2660 |

| NSAIDs (Indomethacin and naproxen) b | N-Acetylcysteine |

| Vidofludimus | Artesunate |

| Brequinar | Povidone-iodine solution |

| Famotidine | Chlorhexidine |

| VERU-111 | Methylene blue |

| Leflunomide | Inhaled nitric oxide |

| Sirolimus | Poly-alcohols (Resveratrol & quercetin) |

| Plitidepsin | Thymalfasin |

| Cyclosporine | Lactoferrin |

| Deferoxamine | TY027 |

| Atovaquone | XAV-19 |

| Therapy | Type | Mechanism | No. of Interventional Clinical Trials b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tocilizumab (Actemra) | Humanized monoclonal antibody | IL-6 receptor blocker | ~41 |

| Ruxolitinib (Jakafi) | Small molecule | JAK 1 and 2 inhibitor | ~15 |

| Colchicine (Colcrys) | Small molecule | Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome and of microtubule polymerization | ~15 |

| Anakinra (Kineret) | Recombinant non-glycosylated human polypeptide | IL-1 receptor antagonist | ~13 |

| Methylprednisolone (DEPOMedrol) | Small molecule | Intracellular receptor-mediated gene expression & suppression of migration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, among others | ~13 |

| Baricitinib (Olumiant) | Small molecule | JAK 1 and 2 inhibitor | ~12 |

| Sarilumab (Kevzara) | Human monoclonal antibody | IL-6 receptor blocker | ~10 |

| Dexamethasone (Decadron, Active Injection D) | Small molecule | Stimulation of glucocorticoid receptors, suppression of neutrophil migration, suppression of inflammatory mediators production, and reversal of increased capillary permeability | ~10 |

| Sirolimus (Rapamune) | Small molecule | mTOR pathway inhibitor | ~4 |

| Mavrilimumab | Human monoclonal antibody | GM-CSF receptor blocker | ~4 |

| Siltuximab (Sylvant) | Chimeric monoclonal antibody | Anti-IL-6 | ~2 |

| Canakinumab (Ilaris) | Human monoclonal antibody | Anti-IL-1β | ~2 |

| Therapy | Type | Mechanism | No. of Interventional Clinical Trials b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unfractionated heparin or Low molecular weight heparins (Enoxaparin, Dalteparin, Tinzaparin, and others) | Sulfated glycosaminoglycans | Activation of antithrombin to inhibit thrombin and factor Xa | ~23 |