Rethinking Fuelwood: People, Policy and the Anatomy of a Charcoal Supply Chain in a Decentralizing Peru

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Who are the actors along the supply chain and what are their roles?

- How are activities and relations distributed amongst and utilized by those actors?

- How are economic and power benefits in charcoal trade distributed amongst actors?

- What are the obstacles and opportunities for a more equitable charcoal supply chain within a multi-level governance context?

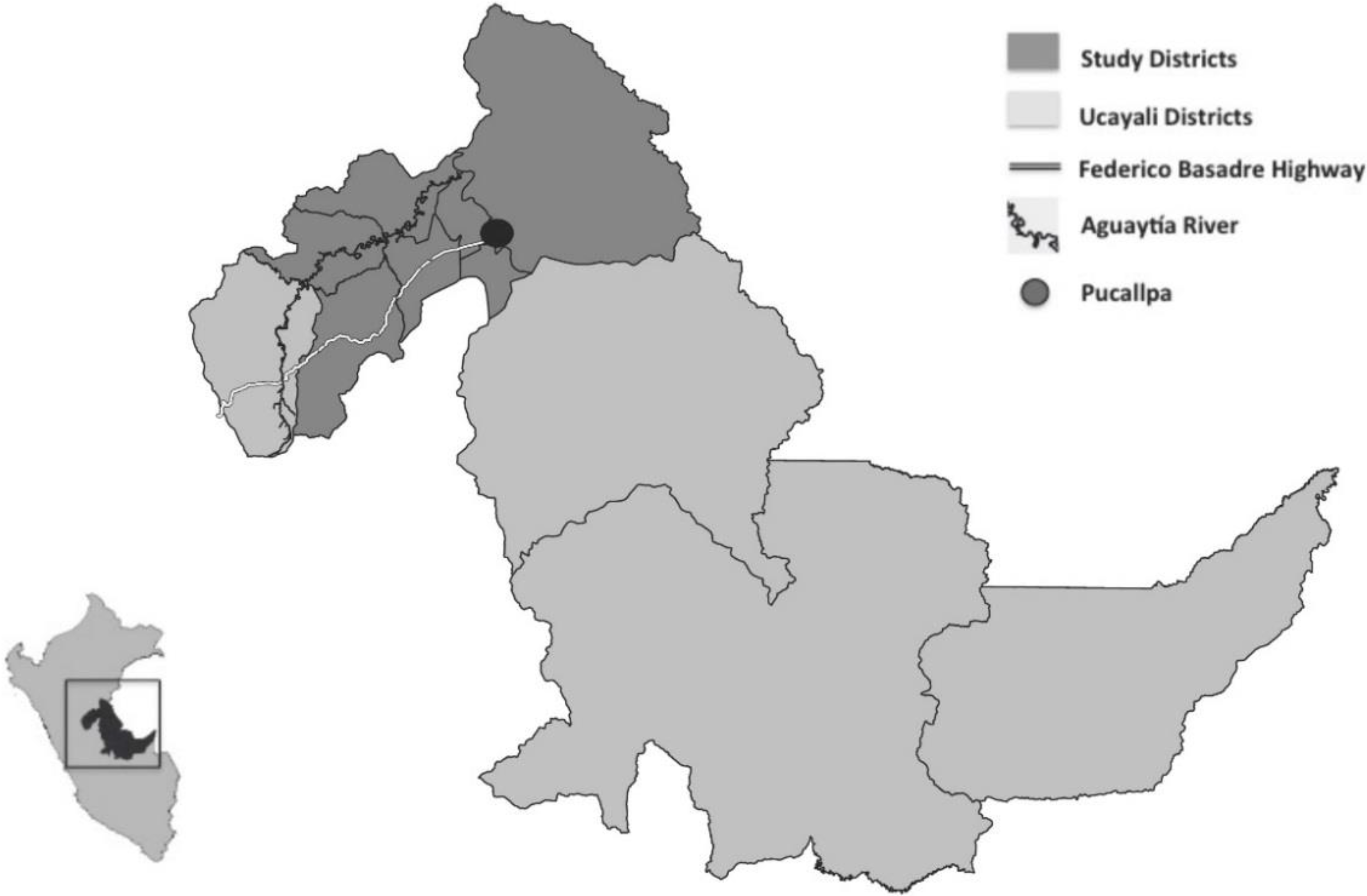

2. Study Site

3. Method

3.1. Non-Probability Sampling and Choosing Informants

3.2. Questionnaires

4. Results

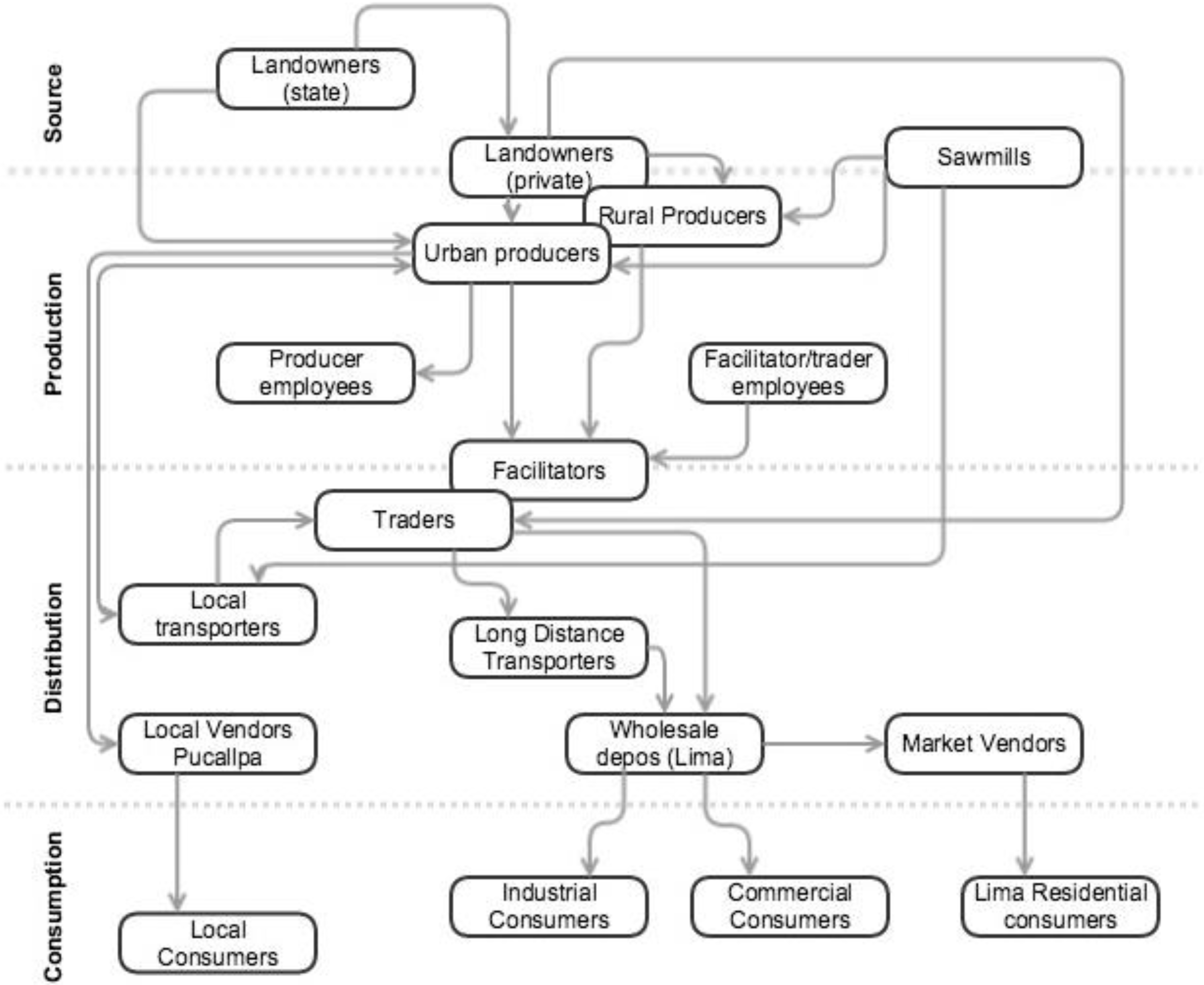

4.1. Who Are the Actors Along the Supply Chain and What Are Their Roles?

4.1.1. Actors

4.1.2. How Are Activities and Relations Distributed Amongst and Utilized by Those Actors?

4.1.3. The Importance of Kin

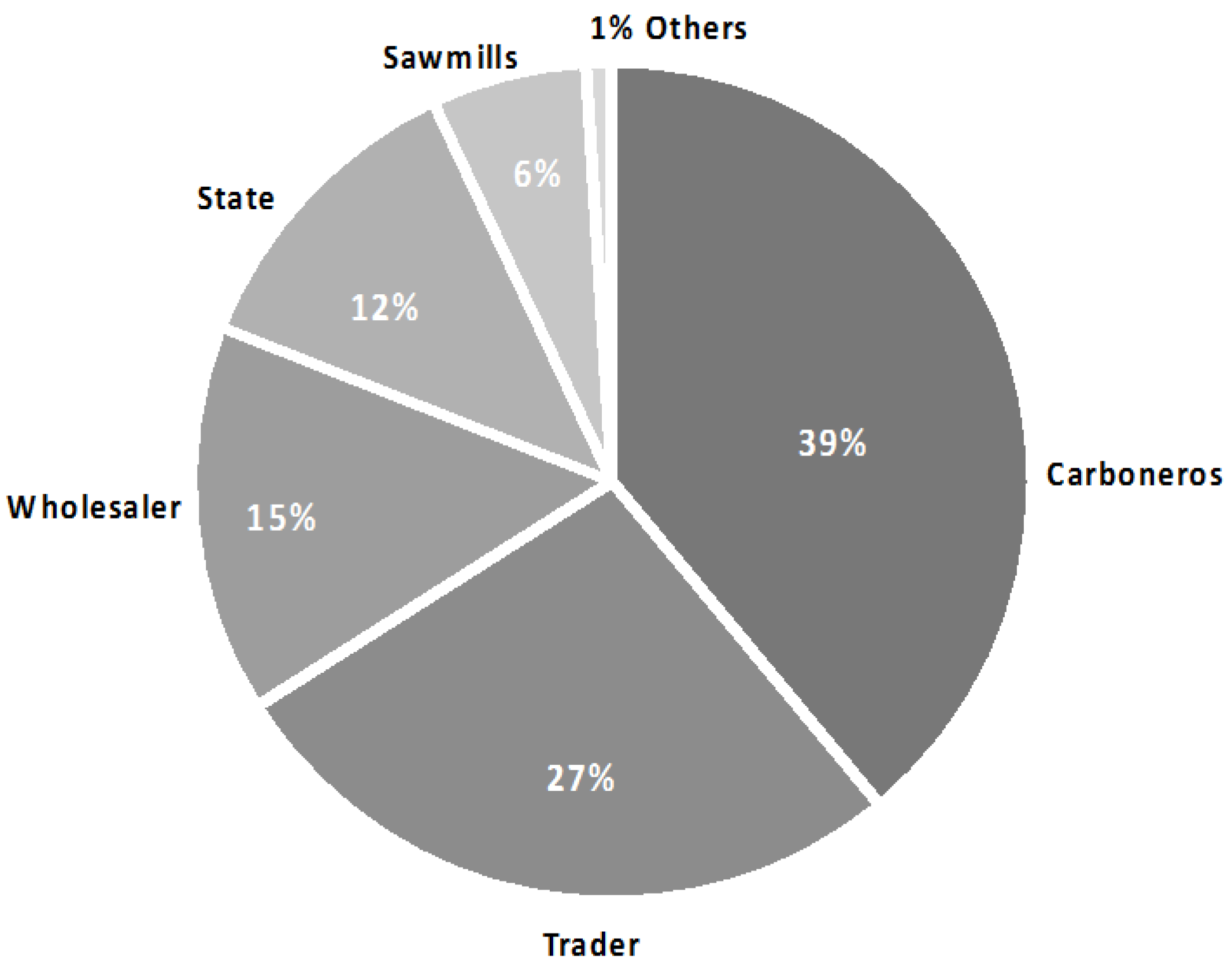

4.2. How Are Economic Benefits in Charcoal Trade Distributed Amongst Actors?

4.3. What Are the Obstacles to and Opportunities for a More Equitable Charcoal Supply Chain in a Governance Context?

Case Studies

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coomes, O.T.; Burt, G.J. Peasant Charcoal Production in the Peruvian Amazon: Rainforest use and economic reliance. For. Ecol. Manag. 2001, 140, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett-Curry, A.; Malhi, Y.; Menton, M. Leakage effects in natural resource supply chains: A case study from the Peruvian commercial charcoal market. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2013, 20, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINAG. Peru Forestal en Números; MINAG: Lima, Peru, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- MINAGRI. Peru Forestal en Números; MINAGRI: Lima, Peru, 2015.

- Ribot, J.C. Waiting for Democracy: The Politics of Choice in Natural Resource Decentralization; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, S.; Cowishaw, G.; Rowcliffe, M.J. Anatomy of a Bushmeat Commodity Chain in Takoradi, Ghana. J. Peasant. Stud. 2003, 31, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, J. Unpredictable outcomes in forestry—Governance institutions in practice. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2014, 27, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newing, J.; Fritch, O. Environmental governance: Participatory, multi-level—And effective? Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendra, H.; Ostrom, E. Polycentric governance of multifunctional forested landscapes. Int. J. Commons. 2012, 6, 104–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelsen, A.; Jagger, P.; Babigumira, R.; Belcher, B.; Hogarth, N.J.; Bauch, S.; Börner, J.; Smith-Hall, C.; Wunder, S. Environmental income and rural livelihoods: A global-comparative analysis. World Dev. 2014, 64, S12–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Persha, L.; Andersson, K. Elite capture risk and mitigation in decentralized forest governance regimes. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 24, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, P.K.; Mookherjee, D. Capture and governance at local and national levels. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J. Access: Forest Profits along Senegal’s Charcoal Commodity Chain. Dev. Chang. 1998, 29, 307–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre Cuadros, M.A.; Menton, M. Descifrando Datos Oficiales Sobre el Consumo de Leña y Carbón Vegetal en el PERÚ; CIFOR: Lima, Peru, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. Peru: Análisis Etnosociodemográfico de las Comunidades Nativas de la Amazonía; INEI: Lima, Peru, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara Salas, S. Ucayali: Análisis de Situación en Población; El Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas, UNFPA: Lima, Peru, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Padoch, C.; Brondizio, E.; Costa, S.; Pinedo-Vasquez, M.; Sears, R.; Siqueira, A. Urban Forest and Rural Cities: Multi-sited Households, Consumption Patterns, and Forest Resources in Amazonia. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.; Ravikumar, A.; Cronkleton, P. The effects of rural development policy on land rights distribution and land use scenarios: The case of oil palm in Peru. Land Use Policy 2017, 70, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schure, J.; Ingram, V.; Sakho-Jimbira, M.S.; Levang, P.; Wiersum, K.F. Formalisation of charcoal value chains and livelihood outcomes in Central- and West Africa. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2012, 17, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordieu, P. Outline of a Theory of Practise; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Labarta-Chávarri, R.A.; White, D.S.; Swinton, S.M. Does Charcoal Production Slow Agricultural Expansion into the Peruvian Amazon Rainforest? World Dev. 2008, 34, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putzel, L.; Peters, C.M.; Romo, M. Post-logging regeneration and recruitment of shihuahuaco (Dipteryx spp.) in Peruvian Amazonia: Implications for management. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.M.; Ribot, J.C. The poverty of forestry policy: Double standards on an uneven playing field. Sustain. Sci. 2007, 2, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, J.C. Improved and more environmentally friendly charcoal production system using a low-cost retort–kiln (Eco-charcoal). Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 1923–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjølie, H.K. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions from households and industry by the use of charcoal from sawmill residues in Tanzania. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 27, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, W. Decentralization Peruvian style: Issues of will and resources. J. Inter-Am. Stud. 2008, 29, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, K. Subnational Economic Nationalism? The contradictory effects of decentralization in Peru. Third World Q. 2010, 31, 1205–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.M.; Vaillancourt, F. Fiscal Decentralization in Developing Countries; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, P.; Mansoor, A. Macroeconomic Development and the Devolution of Fiscal Powers; International Monetary Fund (IMF): Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi, E.; Wardell, A. Multi-level governance of forest resources (Editorial to the special feature). Int. J. Commons 2012, 6, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, S. Voice and Vote: Decentralization and Participation in Post-Fujimori Peru; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, A.; Ravikumar, A.; Paltán, H. The Political Ecology of Oil Palm Company-Community partnerships in the Peruvian Amazon: Deforestation consequences of the privatization of rural development. World Dev. 2018, 109, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollerías Que Usen Carbón Ilegal Pagarán Multa de 1 UIT. Available online: http://eltiempo.pe/pollerias-usen-carbon-ilegal-pagaran-multa-1-uit/ (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- Sears, R.R.; Pinedo-Vasquez, M. Forest policy reform and the organization of logging in Peruvian Amazonia. Dev. Chang. 2011, 42, 609–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.; Martin, A. Who Owns the World’s Forests; Forest Trends: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Banuri, T.; Marglin, F.A. Who Will Save the forests? Knowledge, Power and Environmental Destruction; Zed Books: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- WWF. Sky Rainforest Rescue: Piloting Approaches for Benefit Sharing and Strengthening Local Level Forest Governance, as an Example of How REDD+ Can Deliver Benefits to Local Communities; WWF: Swiss, Grand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| 1. Landowners | Landowners provide space to build charcoal kilns. In rural areas, kilns are frequently built in farm fields, either by the farmer or by itinerate carboneros, to produce charcoal in situ using remnant wood from forest clearance. On public lands itinerate carboneros build kilns in inactive forest concessions using logging waste wood. In urban areas, Timber companies build kilns on property around their sawmills to use mill waste. Carboneros also build kilns on private and public urban lots to transform mill wastes into charcoal. Many producers buy or rent kiln sites, but the government also allow the poor to build on marginal public lands. |

| 2. Sawmill wood transporters (local) | Small-scale entrepreneurs buy sawmill waste-wood to transport and resell at urban kiln sites. Prices vary by distance. |

| 3. Charcoal Producers (carboneros) | All carboneros urban and rural alike utilize artisanal kiln methods. |

| 3.1 Artisanal (rural & urban) | Rural carboneros tend to make charcoal opportunistically as they clear farmland, or else harvest scraps left behind in abandoned concessions and farmlands. |

| 3.2 Super Carbonero | Super carboneros increase the scale of their operations by hiring labour on large plots to manage multiple kilns. They have appeared with the recent increase in value of Amazonian charcoal and are beginning to dominate the market by buying up all the by-product of the quality hardwood shihuahuaco (Dipteryx spp.). |

| 3.3 Carbonero Employees | Super carboneros as well as urban carbonero communities sometimes employ people to tend the kilns, especially at night. |

| 4. Creditors/Facilitators | Creditors lend money and/or goods to carboneros in return for varying degrees of commitment and returns such as reduced charcoal prices or contractual sale agreements. |

| 5. Traders | Traders are the crux of the commodity chain and bear the most fiscal and administrative responsibility for the transport and trade of commercial charcoal. Traders are often also creditors. They buy the charcoal from carboneros, organise charcoal transport to and distribute to wholesalers in Lima. |

| 6. Local Vendors | Local vendors in Pucallpa mainly distribute from the main central markets. They sell sacks half the weight of commercial sacks. This charcoal is inferior in quality because of the wood species used and the small size of the pieces of wood. |

| 7. Transporters (long haul) | Traders hire drivers to transport charcoal in 30,000 kilo loads to Lima. Drivers are often family members or well-known associates of the trader. |

| 8. Wholesale Depository owners | Wholesalers buy vast quantities of charcoal on a weekly basis and distribute in bulk to large urban businesses. Wholesalers are almost always kin of traders. |

| 9. Lima Market Vendors | Market Vendors in Lima distribute to street food sellers, small informal restaurant businesses and domestic clients. |

| 10. Urban Consumers | Commercial and Industrial consumers buy charcoal in bulk from wholesalers. Residential consumers buy from markets. |

| Principal actors involved in the commercial charcoal supply chain between Ucayali and Lima, their roles and relations. | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bennett, A.; Cronkleton, P.; Menton, M.; Malhi, Y. Rethinking Fuelwood: People, Policy and the Anatomy of a Charcoal Supply Chain in a Decentralizing Peru. Forests 2018, 9, 533. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9090533

Bennett A, Cronkleton P, Menton M, Malhi Y. Rethinking Fuelwood: People, Policy and the Anatomy of a Charcoal Supply Chain in a Decentralizing Peru. Forests. 2018; 9(9):533. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9090533

Chicago/Turabian StyleBennett, Aoife, Peter Cronkleton, Mary Menton, and Yadvinder Malhi. 2018. "Rethinking Fuelwood: People, Policy and the Anatomy of a Charcoal Supply Chain in a Decentralizing Peru" Forests 9, no. 9: 533. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9090533

APA StyleBennett, A., Cronkleton, P., Menton, M., & Malhi, Y. (2018). Rethinking Fuelwood: People, Policy and the Anatomy of a Charcoal Supply Chain in a Decentralizing Peru. Forests, 9(9), 533. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9090533