The Effects of Forest Bathing on Stress Recovery: Evidence from Middle-Aged Females of Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

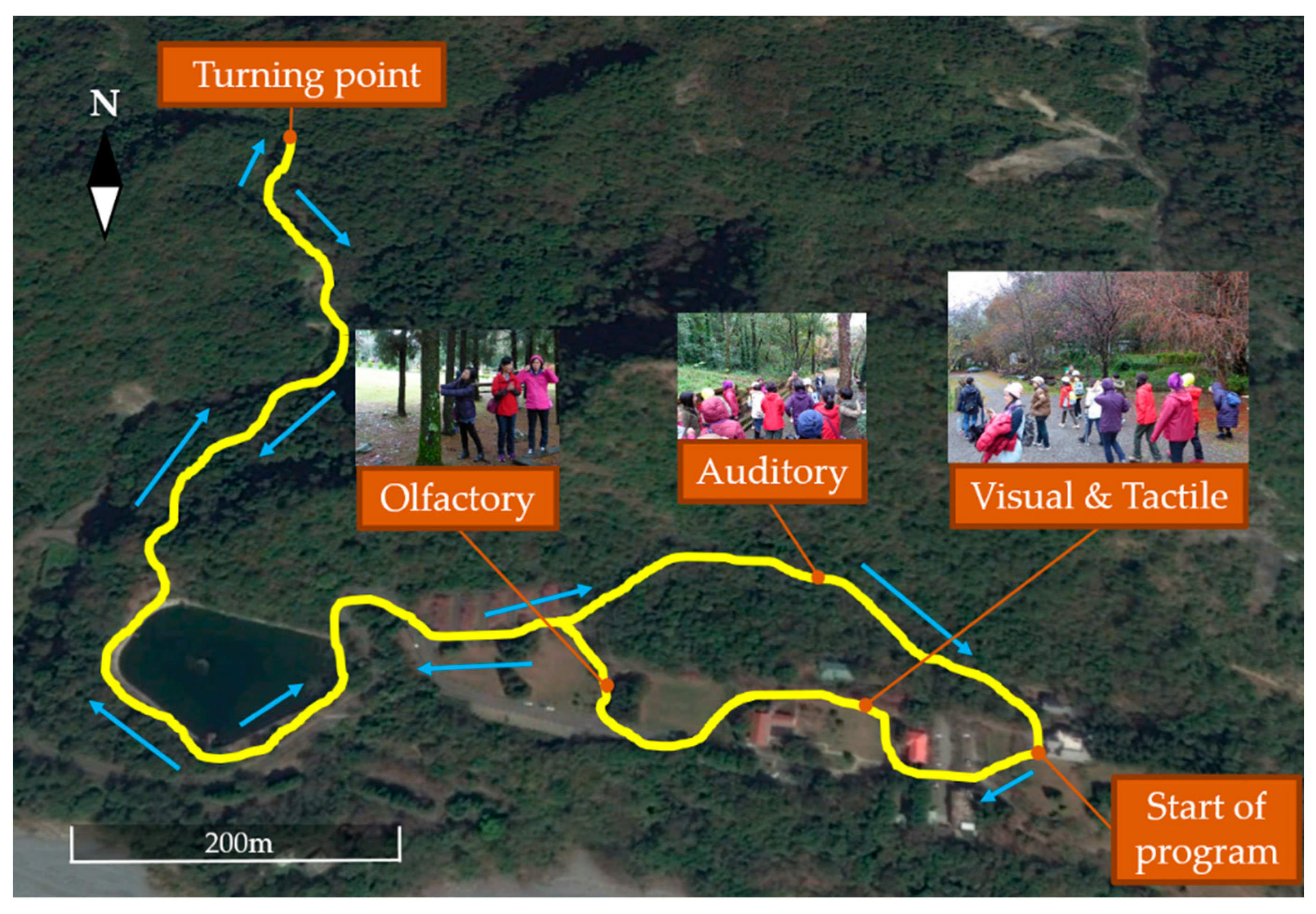

2.2. Study Sites

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Measurements

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychological Effect

4.2. Physiological Effect

4.2.1. Response of Pulse Rate

4.2.2. Response of Blood Pressure

4.2.3. Response of SAA

4.3. Experimental Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Hirano, H.; Kagawa, T.; Sato, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the atmosphere of the forest)—Using salivary cortisol and cerebral activity as indicators. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2007, 26, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.I.; Kobayashi, M.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Li, Y.; Wakayama, Y.; et al. A forest bathing trip increases human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins in female subjects. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2008, 22, 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, G.X.; Cao, Y.B.; Lan, X.G.; He, Z.H.; Chen, Z.M.; Wang, Y.Z.; Hu, X.L.; Lv, Y.D.; Wang, G.F.; Yan, J. Therapeutic effect of forest bathing on human hypertension in the elderly. J. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, E.; Fukuda, S.; Nagano, J.; Hamajima, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Iwai, Y. Psychological effects of forest environments on healthy adults: Shinrin-yoku (forest-air bathing, walking) as a possible method of stress reduction. Public Health 2007, 121, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Human Behavior and Environment; Altman, I., WohlwiIl, J.F., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 6, pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tsunetsugu, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, B.J.; Tyrväinen, L.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological effects of viewing urban forest landscapes assessed by multiple measurements. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 113, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, N.; Saito, H.; Fujiwara, A.; Horiuchi, M. The effect of slight thinning of managed coniferous forest on landscape appreciation and psychological restoration. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2017, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.K.; Kim, D.J.; Kyunghee, J.C.; Son, Y.J.; Koo, J.W.; Min, J.A.; Chae, J.H. Differences of psychological effects between meditative and athletic walking in a forest and gymnasium. Scand. J. For. Res. 2013, 28, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Igarashi, M.; Takagaki, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological effects of a walk in urban parks in fall. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14216–14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Miura, T.; Taue, M.; Kagawa, T.; Li, Q.; Kumeda, S.; Imai, Mo.; Miyazaki, Y. Effect of forest walking on autonomic nervous system activity in middle-aged hypertensive individuals: A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 2687–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.P.; Lin, C.M.; Tsai, M.J.; Tsai, Y.C.; Chen, C.Y. Effects of short forest bathing program on autonomic nervous system activity and mood states in middle-aged and elderly individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.J.; Ishii, H.; Hirano, H.; Kagawa, T.; Morikawa, T. Physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the atmosphere of the forest) in an old-growth broadleaf forest in Yamagata Prefecture, Japan. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2007, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Ohira, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Effect of forest bathing on physiological and psychological responses in young Japanese male subjects. Public Health 2011, 125, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Ishii, H.; Furuhashi, S.; Hirano, H.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the atmosphere of the forest) in a mixed forest in Shinano Town, Japan. Scand. J. For. Res. 2008, 23, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Takayama, N.; Park, B.J.; Li, Q.; Song, C.; Komatsu, M.; Ikei, H.; Tyrväinen, L.; Kagawa, T.; et al. Influence of forest therapy on cardiovascular relaxation in young adults. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 834360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komori, T.; Mitsui, M.; Togashi, K.; Matsui, J.; Kato, T.; Uei, D.; Shibayama, A.; Yamato, K.; Okumura, H.; Kinoshita, F. Relaxation effect of a 2-Hour walk in Kumano-Kodo Forest. J. Neurol. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Deguchi, M.; Miyazaki, Y. The effects of exercise in forest and urban environments on sympathetic nervous activity of normal young adults. J. Int. Med. Res. 2006, 34, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.I.; Kobayashi, M.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Li, Y.J.; Wakayama, Y.; et al. Visiting a forest, but not a city, increases human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2008, 21, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forestry Bureau, Council of Agriculture, Execute Yuan. Available online: https://www.forest.gov.tw/File.aspx?fno=66702 (accessed on 12 May 2018).

- Medlineplus. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/menopause.html#cat_77 (accessed on 12 May 2018).

- Yu, Y.M.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Yoon, S.B.; Shin, C.S. Effects of forest therapy camp on quality of life and stress in postmenopausal women. For. Sci. Technol. 2016, 12, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, H.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Miura, T.; Kagawa, T.; Li, Q.; Kumeda, S.; Imai, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological effects of a forest therapy program on middle-aged females. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 15222–15232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochiai, H.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Miura, T.; Kagawa, T.; Li, Q.; Kumeda, S.; Imai, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological effects of forest therapy on middle-aged males with high-normal blood pressure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 2532–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, H.J.; Shen, I.L. Impact of tourism development and ecotourism to the residents-a case study of Aowanda National Forest Recreation Area. J. Isl. Tour. Res. 2015, 8, 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.C.; Lu, J.H. The revision of profile of mood state questionnaire. Sport Exerc. Res. 2001, 3, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D. Manual for the State-Trait. Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S.K.; Long, C.F. A study of the revised State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Psychol. Test. 1984, 31, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nater, U.M.; Rohleder, N.; Gaab, J.; Berger, S.; Jud, A.; Kirschbaum, C.; Ehlert, U. Human salivary alpha-amylase reactivity in a psychosocial stress paradigm. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2005, 55, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nater, U.M.; Rohleder, N. Salivary alpha-amylase as a non-invasive biomarker for the sympathetic nervous system: Current state of research. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, J.A.; Geus, E.J.; Veerman, E.C.; Hoogstraten, J.; Nieuw Amerongen, A.V. Innate secretory immunity in response to laboratory stressors that evoke distinct patterns of cardiac autonomic activity. Psychosom. Med. 2003, 65, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, G.X.; Lan, X.G.; Cao, Y.B.; Chen, Z.M.; He, Z.H.; Lv, Y.D.; Wang, Y.Z.; Hu, X.L.; Wang, G.F.; Yan, J. Effects of short-term forest bathing on human health in a broad-leaved evergreen forest in Zhejiang Province, China. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2012, 25, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, K.; Anoosheh, M.; Foroughan, M.; Kazemnejad, A. Barriers to middle-aged women’s mental health: A qualitative study. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2014, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/depression/seasonal-affective-disorder (accessed on 15 June 2018).

- Molin, J.; Mellerup, E.; Bolwig, T.; Scheike, T.; Dam, H. The influence of climate on development of winter depression. J. Affect. Disord. 1996, 37, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyall, L.M.; Wyse, C.A.; Morales, C.A.C.; Lyall, D.M.; Cullen, B.; Mackay, D.; Ward, J.; Graham, N.; Strawbridge, R.J.; Gill, J.M.R.; et al. Seasonality of depressive symptoms in women but not in men: A cross-sectional study in the UK Biobank cohort. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 229, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J.; Pretty, J. What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3947–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Restorative effects of viewing real forest landscapes, based on a comparison with urban landscapes. Scand. J. For. Res. 2009, 24, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Miyazaki, Y. Evaluating the relaxation effects of emerging forest-therapy tourism: A multidisciplinary approach. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard Health Publishing. Available online: https://www.health.harvard.edu/press_releases/women-especially-older-women-need-to-pay-more-attention-to-blood-pressure (accessed on 12 May 2018).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/about.htm (accessed on 12 May 2018).

- Horiuchi, M.; Endo, J.; Akatsuka, S.; Uno, T.; Hasegawa, T. Influence of forest walking on blood pessure, Profile of Mood States and stress markers from the viewpoint of aging. J. Aging Gerontol. 2013, 1, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hohashi, K.; Kobayashi, N. The effectiveness of a forest therapy (Shinrin-yoku) program for girls aged 12 to 14 years: A crossover study. Stress Sci. Res. 2013, 28, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakane, H.; Asami, O.; Yamada, Y.; Ohira, H. Effect of negative air ions on computer operation, anxiety and salivary chromogranin A-like immunoreactivity. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2002, 46, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Time | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| 14/January/2017 (Sat.) | 13:00~14:00 | Orientation |

| 14:00~15:00 | Psychological and physiological responses pretest | |

| 15:00~17:30 | Guided forest walk in ANFRA | |

| 17:30~19:30 | Dinner | |

| 19:30~20:30 | Forest walking | |

| 15/January/2017 (Sun.) | 7:00~8:00 | Breakfast |

| 8:00~11:00 | DIY Handcrafts (essential oil body wash) | |

| 11:00~12:00 | Physiological and psychological responses posttest |

| Variables | Pretest | Posttest | t | p | Rate of Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Emotional State (POMS) | |||||

| Confusion | 1.75 ± 0.72 | 1.21 ± 0.31 | −3.514 | 0.003 ** | −31.12 |

| Fatigue | 2.46 ± 1.05 | 1.23 ± 0.36 | −6.127 | 0.000 ** | −50.00 |

| Anger-hostility | 1.29 ± 0.32 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | −3.656 | 0.002 ** | −22.58 |

| Tension | 1.59 ± 0.74 | 1.30 ± 0.48 | −2.162 | 0.047 * | −18.63 |

| Depression | 1.38 ± 0.53 | 1.19 ± 0.40 | −1.126 | 0.278 | −13.64 |

| Vigor | 3.46 ± 0.87 | 4.32 ± 0.53 | 5.014 | 0.000 ** | 25.06 |

| Self-esteem | 4.08 ± 0.64 | 4.30 ± 0.65 | 1.725 | 0.105 | 5.36 |

| Anxiety (STAI-S) | 30.19 ± 8.26 | 25.44 ± 5.15 | −3.341 | 0.004 ** | −15.73 |

| Physiological Indices | Pretest | Posttest | t | p | Rate of Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Pulse rate (Bpm) | 73.44 ± 8.01 | 73.00 ± 9.12 | −0.281 | 0.782 | −0.60 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 122.81 ± 17.7 | 117.19 ± 15.20 | −2.533 | 0.023 * | −4.58 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 86.06 ± 11.89 | 82.56 ± 12.63 | −1.506 | 0.153 | −4.07 |

| Salivary α-amylase (kIU/L) | 25.75 ± 13.94 | 23.19 ± 9.64 | −0.586 | 0.471 | −9.95 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.-T.; Yu, C.-P.; Lee, H.-Y. The Effects of Forest Bathing on Stress Recovery: Evidence from Middle-Aged Females of Taiwan. Forests 2018, 9, 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9070403

Chen H-T, Yu C-P, Lee H-Y. The Effects of Forest Bathing on Stress Recovery: Evidence from Middle-Aged Females of Taiwan. Forests. 2018; 9(7):403. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9070403

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Huan-Tsun, Chia-Pin Yu, and Hsiao-Yun Lee. 2018. "The Effects of Forest Bathing on Stress Recovery: Evidence from Middle-Aged Females of Taiwan" Forests 9, no. 7: 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9070403

APA StyleChen, H.-T., Yu, C.-P., & Lee, H.-Y. (2018). The Effects of Forest Bathing on Stress Recovery: Evidence from Middle-Aged Females of Taiwan. Forests, 9(7), 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9070403