Stakeholder Participation in Natura 2000 Management Program: Case Study of Slovenia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework of the Study

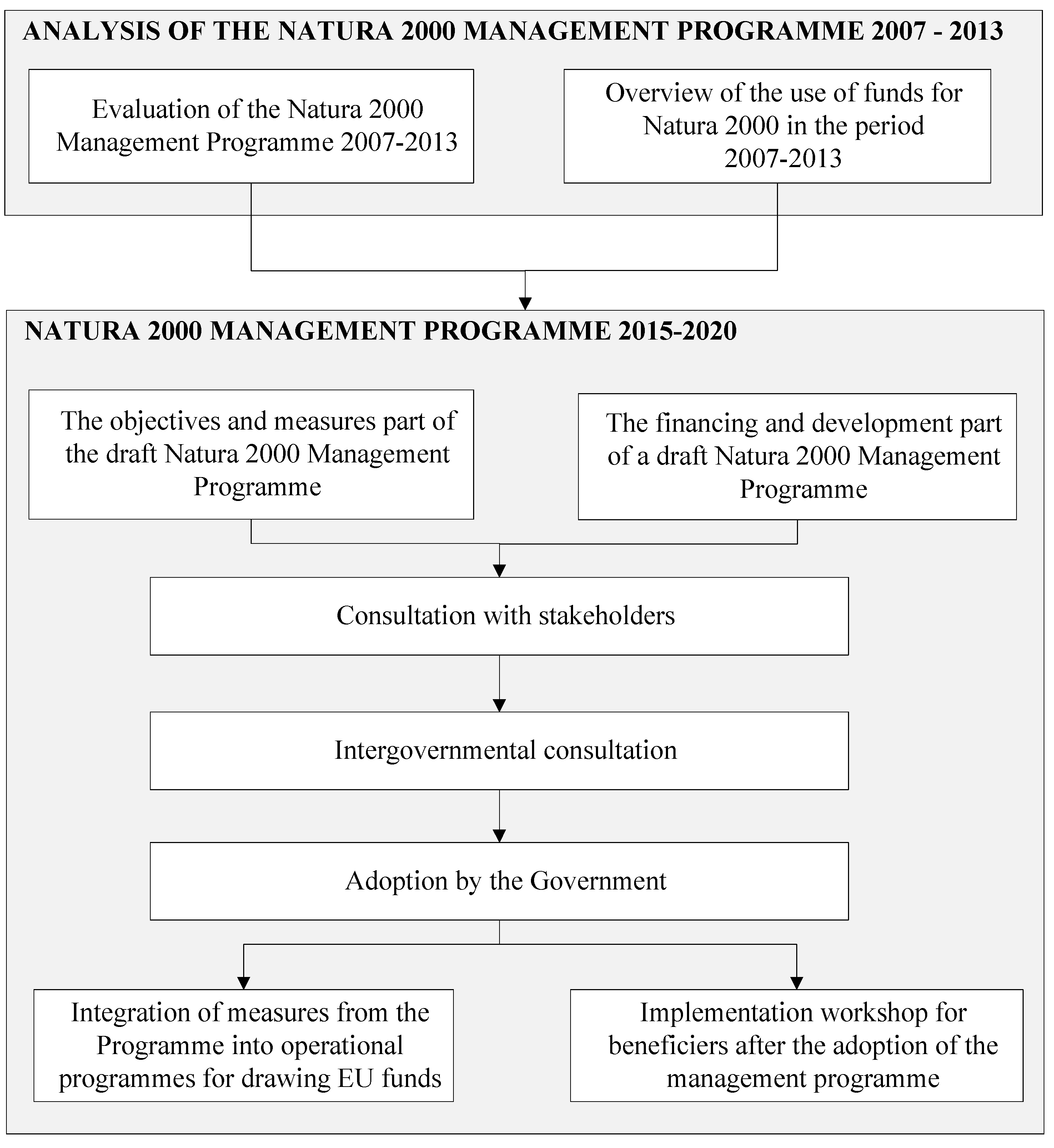

2.1. Natura 2000 Network and Participatory Process in Slovenia

2.2. Theoretical Context

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Interviews with Stakeholders

3.2. Survey of the Stakeholders

4. Results

4.1. Stakeholders’ Evaluation of the Acceptance Criteria

4.1.1. Representativeness of the Participatory Process

4.1.2. Independence of the Participatory Process

4.1.3. Influence in the Participatory Process

4.1.4. Transparency of the Participatory Process

4.2. Stakeholders Evaluation of the Process Criteria

4.2.1. Accessibility of the Participatory Process

4.2.2. Cost-Effectiveness

4.2.3. Task Definition

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sub-Criteria | Agreed | Undefined | Disagreed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness | SFS 1 MESP 1, MESP 2, MESP 3, CAFS 1, FRIS 1, IRSNC 1, IWRS 1, TNP 1, AIS 1, BF 1, FFFRS 1 | CCFF 1, SFS 3, TNP 2 | CAFS 2 SFS 2 |

| Independence | MESP 1, MESP 2, MESP 3, IRSNC 1, SFS 1, SFS 3, SFS 2, IWRS 1, AIS 1, BF 1, CCFF 1, CAFS 1, FRIS 1, FFFRS 1 | TNP 2, CAFS 2 | TNP 1 |

| Influence | MESP 1, MESP 2, MESP 3, IRSNC 1, SFS 1, SFS 2, AIS 1, BF 1, CCFF 1, CAFS 1, FRIS 1, FFFRS 1 | SFS 3, IWRS 1, TNP 1, TNP 2, CAFS 2 | |

| Transparency | MESP 1, MESP 2, MESP 3, IRSNC 1, SFS 1, SFS 2, IWRS 1, TNP 1, TNP 2, AIS 1, CAFS 1, FRIS 1, FFFRS 1 | CCFF 1, CAFS 2 | SFS 3, BF 1 |

| Accessibility | MESP 1, MESP 2, MESP 3, IRSNC 1, SFS 1, SFS 2, IWRS 1, TNP 2, AIS 1, BF 1, CAFS 1, CAFS 2, FRIS 1, FFFRS 1 | CCFF 1 | SFS 3, TNP 1 |

| Cost-effectiveness | MESP 1, MESP 2, MESP 3, IRSNC 1, SFS 1, IWRS 1, CAFS 1, FRIS 1 | SFS 3, SFS 2, TNP 1, CCFF 1, TNP 2, AIS 1, BF 1, CAFS 2, FFFRS 1 | |

| Task definition | MESP 1, MESP 2, MESP 3, IRSNC 1, SFS 1, IWRS 1, CAFS 1, FRIS 1 | SFS 3, SFS 2, TNP 1, TNP 2, AIS 1, BF 1, CCFF 1, CAFS 2, FFFRS 1 |

| Indicators | Mann-Whitney U | Z | p | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management and facilitation of the process | 1926.500 | −0.586 | 0.558 | 3.71 | 0.831 |

| Workshop organization | 2036.00 | −0.165 | 0.869 | 3.80 | 0.848 |

| A broad range of stakeholder involved | 1728.500 | −0.638 | 0.524 | 3.24 | 0.983 |

| Relevance of the involved stakeholders | 1889.000 | −0.383 | 0.701 | 3.18 | 0.937 |

| Access to information | 1887.500 | −0.869 | 0.385 | 3.41 | 0.881 |

| Intelligibility of the material and information | 2122.000 | −0.299 | 0.765 | 3.47 | 0.861 |

| Notifications of certain activities | 1931.500 | −0.904 | 0.366 | 3.11 | 0.951 |

| Stakeholders views are heard and respected | 1851.500 | −0.819 | 0.413 | 3.43 | 1.016 |

| Stakeholders responses and proposals are respected | 1732.000 | −1.043 | 0.297 | 2.99 | 0.976 |

| Power of stakeholders to influence process and its outcomes | 1641.000 | −1.465 | 0.143 | 2.82 | 0.996 |

| Capacity building | 1391.000 | −0.375 | 0.708 | 3.04 | 0.842 |

| Transparency | 1260.500 | −3.018 | 0.003 | 3.26 | 0.917 |

References

- Keulartz, J. European nature conservation and restoration policy—Problems and perspectives. Restor. Ecol. 2009, 17, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Walters, L.; Çil, A. Biodiversity and stakeholder participation. J. Nat. Conserv. 2011, 19, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, N.; Christophersen, T. The influence of non-governmental organisations on the creation of Natura 2000 during the European Policy process. For. Policy Econ. 2002, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kati, V.; Hovardas, T.; Dieterich, M.; Ibisch, P.L.; Mihok, B.; Selva, N. The challenge of implementing the European network of protected areas Natura 2000. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauschmayer, F.; Van den Hove, S.; Koetz, T. Participation in EU biodiversity governance: How far beyond rhetoric? Environ. Plan. Gov. Policy 2009, 27, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beunen, R.; De Vries, J.R. The Governance of Natura 2000 Sites: The Importance of Initial Choices in the Organisation of Planning Processes. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2011, 54, 1041–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šobot, A.; Lukšič, A. The Impact of Europeanisation on the Nature Protection System of Croatia: Example of the Establishment of Multi-Level Governance System of Protected Areas NATURA 2000. Socijalna Ekologija Časopis za Ekološku Misao i Sociologijska Istraživanja Okoline 2017, 25, 235–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferranti, F.; Beunen, R.; Speranza, M. Natura 2000 network: A comparison of the Italian and Dutch implementation experiences. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2010, 12, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cent, J.; Mertens, C.; Niedziałkowski, K. Roles and Impacts of Non Governmental Organizations in Natura 2000 Implementation in Hungary and Poland. Environ. Conserv. 2013, 40, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, L.C.; Paavola, J. Participation in environmental conservation and protected area management in Romania: A review of three case studies. Environ. Conserv. 2013, 40, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrass, L.; Sotirov, M.; Winkel, G. Policy change and Europeanization: Implementing the European Union’s Habitats Directive in Germany and the United Kingdom. Environ. Politics 2015, 24, 788–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel, G.; Blondet, M.; Borrass, L.; Frei, T.; Geitzenauer, M.; Gruppe, A.; Winter, S. The implementation of Natura 2000 in Forests: A trans-and interdisciplinary assessment of challenges and choices. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 52, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Apeldoorn, R.C.; Kruk, R.W.; Bouwma, I.M.; Ferranti, F.; De Blust, G.; Sier, A.R.J. Information and Communication on the Designation and Management of Natura 2000 Sites; The Designation in 27 EU Member States; Main Report 1; EC Publications: Brussel, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sarvašová, Z.; Šálka, J.; Dobšinská, Z. Mechanism of cross-sectoral coordination between nature protection and forestry in the Natura 2000 formulation process in Slovakia. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 127, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, A.; Calado, H.; Cost, L.T.; Bentz, J.; Fonseca, C.; Lobos, A.; Vergilio, M.; Benedicto, J. A Methodological Proposal for the Development of Natura 2000 Sites Management Plans. J. Coast. Res. 2011, 64, 1326–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Margules, C.; Sarkar, S. Systematic Conservation Planning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, G.; Sotirov, M.; Sarvašova, Z. Implementation of Natura 2000 in forests. In European Forest Institute—What Scienec Can Tell Us; Sotirov, M., Ed.; European Forst Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2017; pp. 39–58. Available online: http://www2.efi.int/files/attachments/publications/wsctu7_2017.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2018).

- Blicharska, M.; Orlikowska, E.H.; Roberge, J.M.; Grodzinska-Jurczak, M. Contribution of social science to large scale biodiversity conservation: A review of research about the Natura 2000 network. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 199, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphandéry, P.; Fortier, A. Can a territorial policy be based on science alone? The system for creating the Natura 2000 Network in France. Sociol. Rurals 2001, 41, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiedanpää, J. European-wide conservation versus local well-being: The reception of the Natura 2000 Reserve Network in Karvia, SW—Finland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 61, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, J.; O’Riordan, T.; Nicholson-Cole, S.A.; Watkinson, A.R. Nature conservation for future sustainable shorelines: Lessons from seeking to involve the public. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondet, M.; Koning, J.; Borrass, L.; Ferranti, F.; Geitzenauer, M.; Weiss, G.; Turnhout, E.; Winkel, G. Participation in the implementation of Natura 2000: A comparative study of six EU member states. Land Use Policy 2017, 66, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarikoski, H.; Tikkanen, J.; Leskinen, L.A. Public participation in practice—Assessing public participation in the preparation of regional forest programs in Northern Finland. For. Policy Econ. 2010, 12, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlin, F.; Golob, A.; Habič, Š. Some principles for successful forest conservation management and forestry experiences in establishing the Natura 2000 network. In Legal Aspects of European Forest Sustainable Development, Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium, Zlatibor Mountain, Serbia, 11–15 May 2005; Schmithüsen, F., Herbst, P., Nonic, D., Jovic, D., Stanisic, M., Eds.; ETH Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2005; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Staff Working Document. The EU Environmental Implementation Review Country Report—SLOVENIA. 2017. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/eir/pdf/report_si_en.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2018).

- Petkovšek, M. Slovenian Natura 2000 Network in Numbers; Varstvo Narave: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2017; Volume 30, pp. 99–126. [Google Scholar]

- Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š.; Leban, V.; Krč, J.; Zadnik Stirn, L. Slovenia: Country Report; COOL—Competing Uses of Forest Land: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Medved, M.; Matijašić, D.; Pisek, R. Private property conditions of Slovenian forests in 2010. In Small scale forestry in a Changing World. Opportunities and challenges and the Role of extension and technology transfer. In Proceedings of the IUFRO Conference, Bled, Slovenia, 22–23 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. Influence of Institutions and Forms of Cooperation of Private Forest Owners on Private Forest Management. Ph.D. Thesis, Biotechnical Faculty, Department of Forestry and Renewable Forest Resources, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Balest, J.; Hrib, M.; Dobšinská, Z.; Paletto, A. The formulation of the National Forest Programme in the Czech Republic: A qualitative survey. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 89, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, E.; Kelemen, E.; Kiss, G.; Kaloczkai, A.; Fabok, V.; Mihok, B.; Bela, G. Evaluation of participatory planning: Lessons from Hungarian Natura 2000 management planning processes. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 204, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Primmer, E.; Kyllönen, S. Goals for public participation implied by sustainable development, and the preparatory process of the Finnish National Forest Programme. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 838–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brescancin, F.; Dobšinská, Z.; De Meo, I.; Šálka, J.; Paletto, A. Analysis of stakeholders’ involvement in the implementation of the Natura 2000 network in Slovakia. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 89, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. Public participation methods: A framework for evaluation. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2000, 25, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boh, T. Shielding Implementation from Politicisation? Implementation of the Habitats Directive in Slovenia; OEUE Phase II, Occasional Paper; Dublin European Institute: Dublin, Ireland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, M.; Malovrh, Š.P.; Laktić, T.; De Meo, I.; Paletto, A. Collaboration and conflicts between stakeholders in drafting the Natura 2000 Management Programme (2015–2020) in Slovenia. J. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 42, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlad, B.; Kline, M. Natura 2000. Končno Poročilo o Izvajanju Komunikacijske Strategije. Priloga 10: Priporočila za Upravljanje in Komuniciranje Natura 2000; Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2004.

- Nastran, M.; Pirnat, J. Stakeholder participation in planning of the protected natural areas: Slovenia. Sociologija i Prostor Časopis za Istraživanje Prostornoga i Sociokulturnog Razvoja 2012, 50, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibič, A.; Ogorelec, B.; Podobnik, J.; Mikuletič, J.; Vaupotič, M.; Bedjanič, M.; Midžić, Z.; Trebar, B. Natura 2000 Site Management Programme: 2007–2013 Operational Programme; Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2007; Volume 61.

- Management of State Forests Act. In Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia; No. 9/16 of 12 February 2016; Ljubljana City Library: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2016.

- Dryzek, J.S. Deliberative Democracy and Beyond. Liberals, Critics, Contestations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; p. 195. ISBN 0198295073, 9780198295075. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.G. Impact Assessment and Sustainable Resource Management; Longman: Harlow, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan: London, UK, 1997; ISBN 1403949204, 9781403949202. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, J. Consensus building: Clarification for the critics. Plan. Theory 2004, 3, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webler, T.; Tuler, S.; Krueger, R. What is good participation process? Five perspectives from the public. Environ. Manag. 2001, 27, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, M.; Scarce, R. The Intention Was Good: Legitimacy, Consensus Based Decision Making, and the Case of Forest Planning in British Columbia, Canada. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2004, 17, 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- McGurk, B.; Sinclair, A.; Diduck, A. An assessment of stakeholder advisory committees in forest management: Case studies from Manitoba, Canada. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 809–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyet, V.; Schlaepfer, R.; Parlange, M.B.; Buttler, A. A framework to implement Stakeholder participation in environmental projects. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 111, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J. (Eds.) Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 0 7619 7109 2. [Google Scholar]

- Creative Research Systems: Sample Size Calculator. Available online: https://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm (accessed on 11 September 2018).

- Dillman, D.A. Mail and Internet Survey: The Tailored Design Method, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0471323549. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009; p. 857. [Google Scholar]

- PUN 2000. Life + Management. Available online: http://www.natura2000.si/en/life-management/ (accessed on 18 August 2018).

- Sotirov, M.; Lovric, M.; Winkel, G. Symbolic transformation of environmental governance: Implementation of EU biodiversity policy in Bulgaria and Croatia between Europeanization and domestic politics. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2015, 33, 986–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferranti, F.; Turnhout, E.; Beunen, R.; Behagel, J.H. Shifting nature conservation approaches in Natura 2000 and the implications for the roles of stakeholders. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 57, 1642–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, A.; Heikkilä, J.; Malmivaara-Lämsä, M.; Löfström, I.; Case, P. Evaluation of a participatory urban forest planning process. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 45, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, G.; Tena, J. Monitoring and evaluating participation in national forest programmes. The Catalan case. Schweizerische Zeitschrift fur Forstwesen 2006, 157, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnhout, E.; Behagel, J.; Ferranti, F.; Beunen, R. The construction of legitimacy in European nature policy: Expertise and participation in the service of cost-effectiveness. Environ. Politics 2015, 24, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eben, M. Public participation during site selections for Natura 2000 in Germany: The Bavarian case. In Stakeholder Dialogues in Natural Resources Management; Stollkleemann, S., Welp, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 261–278. ISBN 978-3-540-36916-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kluvánková-Oravská, T.; Chobotová, V.; Banaszak, I.; Slavikova, L.; Trifunovova, S. From government to governance for biodiversity: The perspective of central and Eastern European transition countries. Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecomte, N.; Martineau-Delisle, C.; Nadeau, S. Participatory requirements in forest management planning in Eastern Canada: A temporal and interprovincial perspective. For. Chron. 2005, 81, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gane, M. Forest Strategy: Strategic Management and Sustainable Development for the Forest Sector; Springer: Godalming, UK, 2007; ISBN 9781402059643. [Google Scholar]

- Geitzenauer, M.; Hogl, K.; Weiss, G. The implementation of Natura 2000 in Austria—A European policy in a federal system. Land Use Policy 2016, 52, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, N. Participation or involvement? Development of forest strategies on national and sub-national level in Germany. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 89, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogl, K.; Kvarda, E. The Austrian Forest Dialogue: Introducing a New Mode of Governance Process to a Well Entrenched Sectoral Domain; InFER, University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences: Vienna, Austria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Criteria | Sub-Criteria | Related Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptance criteria | Representativeness | Early involvement |

| Relevance of the involved stakeholders | ||

| A broad range of stakeholders involved | ||

| No stakeholder who is willing to participate is deliberately excluded | ||

| Exclusion of stakeholders from the process | ||

| Independence | Management and facilitation of the process | |

| Equality of stakeholders in the process | ||

| Stakeholders views and opinions are heard | ||

| Influence | Stakeholders responses and proposals are respected | |

| Stakeholders have the power to influence the process and its outcomes | ||

| Capacity building | ||

| Transparency | Transparency of the process | |

| Process criteria | Accessibility | Information resources |

| Material resources | ||

| Time resources | ||

| Cost-effectiveness | Financial resources | |

| Task definition | Nature and scope of a participation process |

| Name of Institution/Organization/Association | N° Respondents |

|---|---|

| Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning | 3 |

| Institute of the Republic of Slovenia for Nature Conservation | 1 |

| Slovenia Forest Service | 3 |

| Institute for Water of the Republic of Slovenia | 1 |

| Triglav National Park | 2 |

| Farmland and Forest Fund of the Republic of Slovenia | 1 |

| University of Ljubljana—Biotechnical Faculty | 1 |

| Agricultural Institute of Slovenia | 1 |

| Centre for Cartography of Fauna and Flora | 1 |

| Chamber of Agriculture and Forestry of Slovenia | 2 |

| Fisheries Research Institute of Slovenia | 1 |

| Total | 17 |

| Group of Stakeholders | N° Sample | N° Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Governmental Organizations | 98 (12.8%) | 26 (9.7%) |

| Public Administrations | 244 (31.9%) | 114 (42.9%) |

| Local Communities | 25 (3.2%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| Environmental NGOs | 19 (2.5%) | 6 (2.3%) |

| Chambers and Associations | 298 (38.9%) | 56 (21.1%) |

| Universities and Research Institutes | 42 (5.4%) | 13 (4.9%) |

| Others | 41 (5.3%) | 11 (4.1%) |

| Total | 767 | 266 (Because the survey was anonymous, 38 (14.3%) respondents choose not to reveal their institution.) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laktić, T.; Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. Stakeholder Participation in Natura 2000 Management Program: Case Study of Slovenia. Forests 2018, 9, 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9100599

Laktić T, Pezdevšek Malovrh Š. Stakeholder Participation in Natura 2000 Management Program: Case Study of Slovenia. Forests. 2018; 9(10):599. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9100599

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaktić, Tomislav, and Špela Pezdevšek Malovrh. 2018. "Stakeholder Participation in Natura 2000 Management Program: Case Study of Slovenia" Forests 9, no. 10: 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9100599

APA StyleLaktić, T., & Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. (2018). Stakeholder Participation in Natura 2000 Management Program: Case Study of Slovenia. Forests, 9(10), 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9100599