Recreation in Different Forest Settings: A Scene Preference Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Forest Preference and Recreation Activities

2.1. Human Intervention

2.2. Biodiversity

2.3. Forest Experience

2.4. The Present Study

3. Method

3.1. Participants

| Social science students (n = 75) | Forestry students (n = 31) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 48% | 52% | |

| Mean age | 24 years (3.1) | 22 years (2.4) | |

| Childhood place of residence *** | |||

| 200 or fewer residents | 10 | 42 | |

| 201–10,000 residents | 30 | 45 | |

| 10,001–100,000 residents | 38 | 13 | |

| 100,001 or more residents | 22 | 0 | |

| Distance to closest forest | 1.3 km (1.8) | 0.8 km (0.8) | |

| Frequency of forest recreation activities a | |||

| Walking | 3.04 (0.83) | 3.71 (0.69) *** | |

| Going on outings | 2.19 (0.51) | 2.52 (0.77) * | |

| Picking berries or mushrooms | 2.08 (0.59) | 2.68 (0.87) *** | |

| Exercising | 3.21 (0.98) | 3.80 (0.71) ** | |

| Studying plants and animals | 1.72 (0.48) | 2.26 (0.77) *** | |

| Production values b | 3.93 (1.21) | 5.29 (0.94) *** | |

| Recreation values b | 4.66 (1.31) | 4.10 (1.56) | |

| Ecological values b | 6.05 (1.13) | 6.29 (0.74) | |

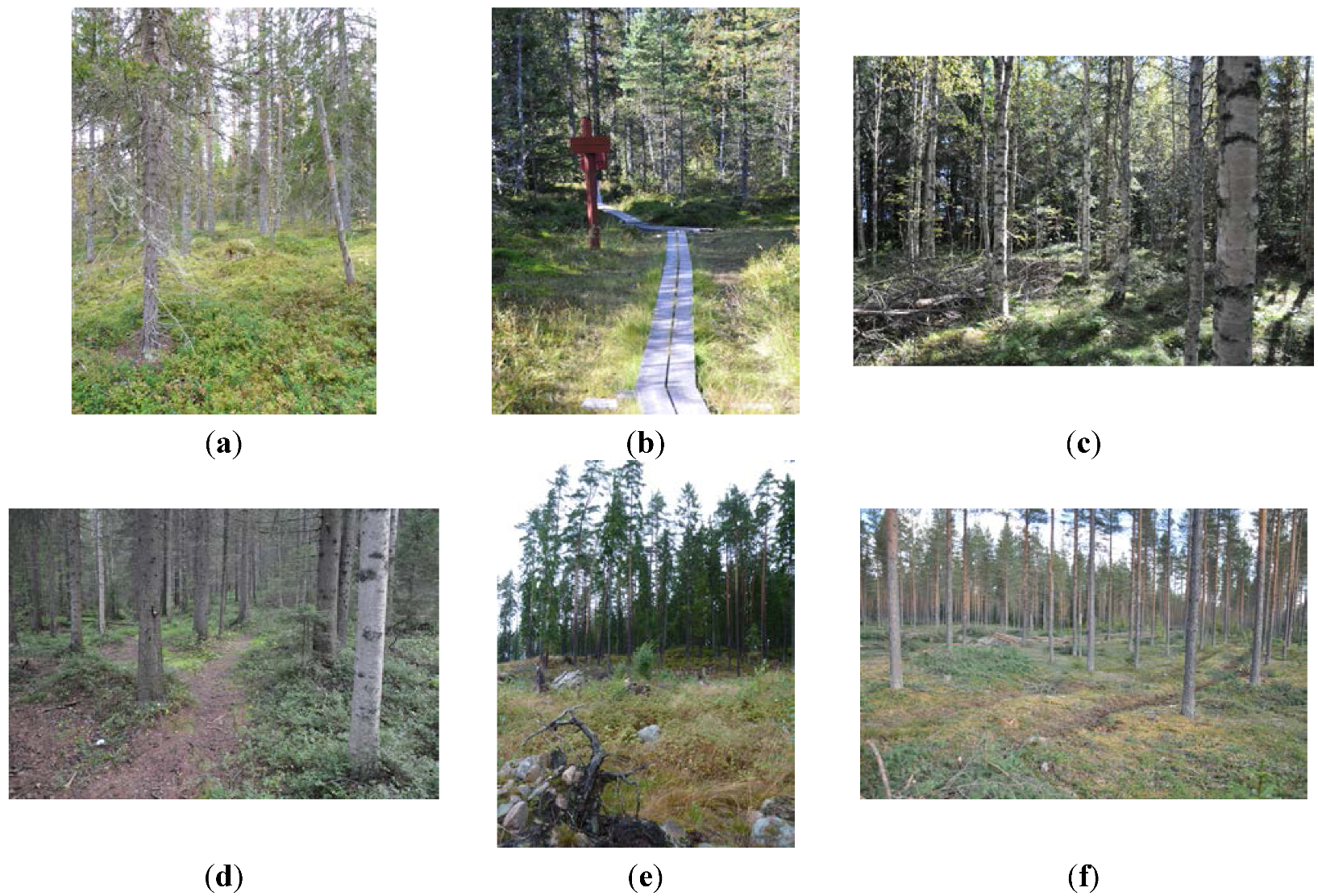

3.2. Environmental Stimuli

| Type of human intervention | Level of biodiversity | Type of forest | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coniferous | Mixed | |||

| Natural-looking | Low | 2 | 2 | |

| High | 2 | 2 | ||

| Recreation | Low | 2 | 2 | |

| High | 2 | 2 | ||

| Forest management | - | - | - | 6 |

3.3. Measures of Subjects’ Attributes

3.4. Procedure

4. Results

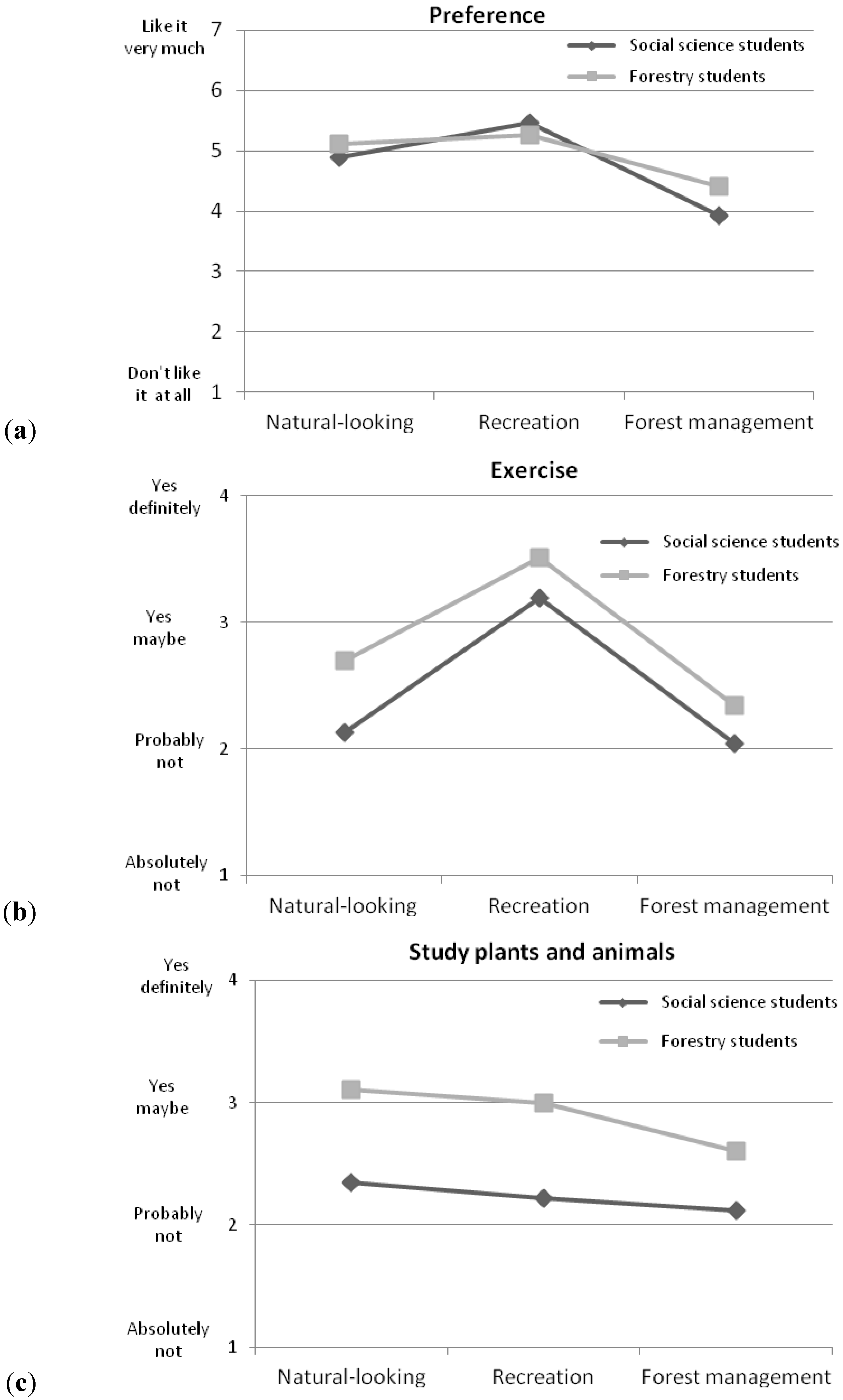

4.1. Type of Human Intervention

| Internal reliability (α), means and standard deviations | Repeated measures ANOVAs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural-looking (n = 8) | Recreation (n = 8) | Forest management (n = 6) | Main effect: Scene | Main effect: Group | Interaction: Scene and Group | ||

| Preference | α = 0.77 | α = 0.71 | α = 0.74 | ||||

| Social science students | 4.90 (0.85) | 5.47 (0.71) | 3.92 (0.94) | F = 67.55 p = 0.001 partial η2 = 0.39 | n.s. | F = 5.302 p = 0.01 partial η2 = 0.05 | |

| Forestry students | 5.11 (0.66) | 5.27 (0.69) | 4.41 (0.87) | ||||

| Total | 4.96 (0.80) | 5.41 (0.71) | 4.07 (0.95) | ||||

| Walk | α = 0.83 | α = 0.75 | α = 0.75 | F = 189.41 p = 0.001 partial η2 = 0.65 | F = 5.81 p = 0.02 partial η2 = 0.05 | n.s. | |

| Social science students | 2.95 (0.56) | 3.67 (0.35) | 2.51 (0.55) | ||||

| Forestry students | 3.25 (0.44) | 3.77 (0.26) | 2.68 (0.63) | ||||

| Total | 3.04 (0.54) | 3.70 (0.33) | 2.56 (0.58) | ||||

| Outings | α = 0.75 | α = 0.75 | α = 0.64 | F = 78.77 p = 0.001 partial η2 = 0.43 | F = 5.97 p = 0.02 partial η2 = 0.05 | n.s. | |

| Social science students | 2.51 (0.52) | 2.84 (0.53) | 2.10 (0.48) | ||||

| Forestry students | 2.85 (0.47 ) | 2.98 (0.53) | 2.20 (0.46) | ||||

| Total | 2.61 (0.53) | 2.88 (0.54) | 2.13 (0.47) | ||||

| Pick berries or mushrooms | α = 0.87 | α = 0.82 | α = 0.82 | F = 71.52 p = 0.001 partial η2 = .41 | F = 7.53 p = 0.01 partial η2 = 0.07 | n.s. | |

| Social science students | 3.00 (0.61) | 2.58 (0.57) | 2.46 (0.63) | ||||

| Forestry students | 3.36 (0.31) | 2.76 (0.45) | 2.78 (0.57) | ||||

| Total | 3.10 (0.56) | 2.63 (0.54) | 2.56 (0.63) | ||||

| Exercise | α = 0.91 | α = 0.84 | α = 0.84 | F = 220.11 p = 0.001 partial η2 = 0.68 | F = 12.51 p = 0.001 partial η2 = 0.11 | F = 3.31 p = 0.05 partial η2 = 0.03 | |

| Social science students | 2.13 (0.71) | 3.19 (0.58) | 2.04 (0.65) | ||||

| Forestry students | 2.70 (0.58) | 3.51 (0.30) | 2.34 (0.61) | ||||

| Total | 2.29 (0.72) | 3.28 (0.54) | 2.12 (0.65) | ||||

| Study plants and animals | α = 0.94 | α = 0.92 | α = 0.89 | F = 32.58 p = 0.001 partial η2 = 0.24 | F = 25.33 p = 0.001 partial η2 = 0.20 | F = 6.35 p = 0.01 partial η2 = 0.06 | |

| Social science students | 2.35 (0.79) | 2.22 (0.69) | 2.12 (0.72) | ||||

| Forestry students | 3.11 (0.44) | 3.00 (0.48) | 2.60 (0.55) | ||||

| Total | 2.57 (0.79) | 2.45 (0.72) | 2.26 (0.71) | ||||

4.2. Level of Biodiversity

4.3. Summary of Findings

| Internal reliability (α), means and standard deviations | Repeated measures ANOVAs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low biodiversity (n = 8) | High biodiversity (n = 8) | Main effect: Scene | Main effect: Group | Interaction: Scene and Group | ||

| Preference | α = 0.64 | α = 0.66 | ||||

| Social science students | 5.09 (0.71) | 5.28 (0.71) | F = 11.41 p = 0.001 partial η2 = 0.10 | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Forestry students | 5.07 (0.57) | 5.31 (0.65) | ||||

| Total | 5.09 (0.67) | 5.29 (0.69) | ||||

| Walk | α = 0.71 | α = 0.73 | ||||

| Social science students | 3.29 (0.38) | 3.32 (0.43) | n.s. | F = 7.26 p = 0.01 partial η2 = 0.07 | n.s. | |

| Forestry students | 3.48 (0.34) | 3.54 (0.34) | ||||

| Total | 3.35 (0.38) | 3.39 (0.42) | ||||

| Outings | α = 0.72 | α = 0.69 | ||||

| Social science students | 2.61 (0.49) | 2.73 (0.50) | n.s. | F = 6.40 p = 0.01 partial η2 = 0.06 | n.s. | |

| Forestry students | 2.91 (0.44) | 2.92 (0.50) | ||||

| Total | 2.70 (0.49) | 2.79 (0.51) | ||||

| Pick berries or mushrooms | α = 0.81 | α = 0.82 | ||||

| Social science students | 2.78 (0.53) | 2.79 (0.60) | n.s. | F = 6.66 p = 0.01 partial η2 = 0.06 | n.s. | |

| Forestry students | 3.06 (0.35) | 3.05 (0.34) | ||||

| Total | 2.86 (0.50) | 2.87 (0.55) | ||||

| Exercise | α = 0.81 | α = 0.85 | ||||

| Social science students | 2.71 (0.54) | 2.61 (0.61) | F = 4.28 p = 0.04 partial η2 = 0.04 | F = 16.13 p = 0.001 partial η2 = 0.13 | n.s. | |

| Forestry students | 3.12 (0.34) | 3.08 (0.49) | ||||

| Total | 2.83 (0.53) | 2.75 (0.62) | ||||

| Study plants and animals | α = 0.93 | α = 0.93 | ||||

| Social science students | 2.23 (0.69) | 2.34 (0.78) | F = 23.84 p = 0.001 partial η2 = 0.19 | F = 30.98 p = 0.001 partial η2 = 0.23 | n.s. | |

| Forestry students | 2.95 (0.45) | 3.15 (0.44) | ||||

| Total | 2.44 (0.71) | 2.58 (0.79) | ||||

5. Discussion

5.1. Activity Preferences in Forest Settings

5.2. Forest Recreation and Setting Experience

5.3. Forest Recreation and Biodiversity

5.4. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Pouta, E.; Sievänen, T.; Neuvonen, M. Recreational wild berry picking in Finland—Reflection of a rural life style. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roovers, P.; Hermy, M.; Gulinck, H. Visitor profile, perceptions and expectations in forests from a gradient of increasing urbanization in central Belgium. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 59, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribe, R.G. Scenic beauty perceptions along the ROS. J. Environ. Manag. 1994, 42, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainen, E.; Sarjala, T.; Raitio, H. Promoting human health through forests: Overview and major challenges. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, B.; Frick, J.; Buchecker, M.; Gutscher, H. Influences of personal, social, and environmental factors on workday use frequency of the nearby outdoor recreation areas by working people. Leis. Sci. 2011, 33, 420–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, K.; Markkanen, P. Factors affecting participating in wild berry picking by rural and urban dwellers. Silva Fenn. 2001, 35, 487–495. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, F.S.; Koch, N.E. Twenty-five years of forest recreation research in Denmark and its influence on forest policy. Scand. J. For.Res. 2004, 19, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, L.; Twynam, G.D.; Haider, W.; Robinson, D. Examining the desirability for recreating in logged settings. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2000, 13, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rieper, C.J.; Manning, R.E.; Monz, C.A.; Goonan, K.A. Tradeoffs among resource, social, and managerial conditions on mountain summits of the northern forest. Leis. Sci. 2011, 33, 228–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.C.; Daniel, T.C. Predicting scenic beauty of timber stands. For. Sci. 1986, 32, 471–487. [Google Scholar]

- Ribe, R.G. In-stand scenic beauty of variable retention harvests and mature forests in the U.S. Pacific Northwest: The effects of basal area, density, retention pattern and down wood. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tönnes, S.; Karjalainen, E.; Löfström, I.; Neuvonen, M. Scenic impacts of retention trees in clear-cutting areas. Scand. J. For. Res. 2004, 19, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Kolison, S.H.; Miller, J.H. Public preferences for nontimber benefits of loblolly pine (Pinus taede) stands regenerated by different site preparation methods. South. J. Appl. For. 2000, 24, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Shelby, B.; Thompson, J.R.; Brunson, M.; Johnson, R. A decade of recreation ratings for six silviculture treatments in Western Oregon. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 75, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahvanainen, L.; Tyrväinen, L.; Ihalainen, M.; Vuorela, N.; Kolehmainen, O. Forest management and public perceptions—Visual versus verbal information. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 53, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.N.; Donavan, D.T.; Mishra, S.; Little, T.D. The latent structure of landscape perception: A mean and covariance structure modeling approach. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Right of Public Access, 2011. Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. Available online: http://www.naturvardsverket.se/en/In-English/Start/Enjoying-nature/The-right-of-public-access/ (accessed on 11 June 2012).

- Vilka är ute i naturen? Delresultat från en nationell enkät om friluftsliv och naturturism i Sverige (Who Visits Nature? Results from a Nationwide Questionnaire Study of Outdoor Life and Nature Tourism in Sweden); Report No. 1; Fredman, P.; Karlsson, S.-E.; Romild, U.; Sandell, K. (Eds.) Forskningsprogrammet friluftsliv i förändring: Östersund, Sweden, 2008.

- Kellomäki, S.; Savolainen, R. The scenic value of the forest landscape assessed in field and laboratory. Landsc. Plan. 1984, 11, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, E.H.; Simcox, D.E.; Law, C.S. Perceptual landscape simulations: History and prospect. Landsc. J. 1987, 6, 62–80. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, R.E.; Freimund, W.A. Use of visual research methods to measure standards of quality for parks and outdoor recreation. J. Leis. Res. 2004, 36, 557–579. [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen, V.S.; Frivold, L.H. Public preferences for forest structures: A review of quantitative surveys from Finland, Norway, and Sweden. Urban For. Urban Green. 2008, 7, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribe, R.G. The aesthetics of forestry: What has empirical preference research taught us? Environ. Manag. 1989, 13, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.L. Social Science to Improve Fuels Management: A Synthesis of Research on Aesthetics and Fuels Management; General Technical Report NC-261; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Research Station: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, T.R.; Kutzli, G.E. Preference and perceived danger in field/forest settings. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 819–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Herbert, E.J.; Kaplan, R.; Crooks, C.L. Cultural and developmental comparisons of landscape perceptions and preferences. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Evans, G.W. Psychological Foundations of Nature Experience. In Behavior and Environment: Psychological and Geographical Approaches; Gärling, T., Golledge, R.G., Eds.; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 1993; pp. 427–457. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, A.R.; Bradley, G.A. The effects of viewer attributes on preference for forest scenes: Contributions of attitudes, knowledge, demographic factors, and stakeholder group membership. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 147–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Koole, S.L. New wilderness in the Netherlands: An investigation of visual preferences for nature development landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, E.; Arce, C.; Sabucedo, J.M. Classification of landscapes using quantitative and categorical data, and prediction of their scenic beauty in north-western Spain. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, F.S. The effects of information on Danish forest visitors’ acceptance of various management actions. Forestry 2000, 73, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, S.R.J. Beyond Visual Resource Management: Emerging Theories of an Ecological Aesthetic and Visible Stewardship. In Forests and Landscapes. Linking Ecology, Sustainability, and Aesthetics; IUFRO Research Series 6; Sheppard, S.R.J., Harshaw, H.W., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2001; pp. 149–172. [Google Scholar]

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Sustaining Life on Earth.How the Convention on Biological Diversity Promotes Nature and Human Well-Being; United Nations Environment Programme: Montreal, Canada, 2000.

- Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Sweden’s Environmental Objectives in an Interdependent World—de Facto 2007; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2007.

- Swedish Forest Agency, Quantitative Targets of Swedish Forest Policy; Swedish Forest Agency: Jönköping, Sweden, 2005.

- Nassauer, J.I. Messy ecosystems, orderly frames. Landsc. J. 1995, 14, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, R. Conflict between ecological sustainability and environmental aesthetics: Conundrum, canärd or curiosity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 32, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H. An ecological aesthetic for forest landscape management. Landsc. J. 1999, 18, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen, V.S.; Frivold, L.H. Naturally dead and downed wood in Norwegian boreal forests: Public preferences and the effect of information. Scand. J. For. Res. 2011, 26, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.J.H.; Cary, J. Landscape preferences, ecological quality, and biodiversity protection. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, B.; Buchecker, M. Aesthetic preferences versus ecological objectives in river restorations. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 85, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, T.; Baudains, C. Biodiversity in the front yard: An investigation of landscape preference in a domestic urban context. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 166–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortezza, R.; Corry, R.C.; Sanesi, G.; Brown, R.D. Visual preference and ecological assessments for designed alternative brownfield rehabilitations. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 89, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamps, A.E. Psychology and the Aesthetics of the Built Environment; Kluwer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ribe, R.G. Is scenic beauty a proxy for acceptable management? The influence of environmental attitudes on landscape perceptions. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 757–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, A.R.; Tilt, J.R.; Bradley, G.A. The effects of forest regeneration on preferences for forest treatments among foresters, environmentalists, and the general public. J. For. 2010, 108, 215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk, G.; Möser, G. Intention and behavior: A Bayesian meta-analysis with focus on the Ajzen-Fishbein Model in the field of environmental behavior. Qual. Quant. 2009, 43, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. Meditation, restoration, and the management of mental fatigue. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 480–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Hayes, L.J.; Applin, R.C.; Weatherly, A.M. Compatibility: An experimental demonstration. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Smith, A.; Humphryes, K.; Pahl, S.; Snelling, D.; Depledge, M. Blue space: The importance of water for preference, affect, and restorativeness ratings of natural and built scenes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnström, B.; Gustafsson, L.; Hallingbäck, T.; Jonsell, M.; Weslien, J. Threatened forest plants, animals and fungus species in Swedish forests—Distribution and habitat associations. Conserv. Biol. 1994, 8, 718–731. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canter, D. The purposive evaluation of places. A facet approach. Environ. Behav. 1983, 15, 659–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, G.A.; Kearney, A.R. Public and professional responses to the visual effects of timber harvesting: Different ways of seeing. West.J. Appl. For. 2007, 22, 42–54. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Eriksson, L.; Nordlund, A.M.; Olsson, O.; Westin, K. Recreation in Different Forest Settings: A Scene Preference Study. Forests 2012, 3, 923-943. https://doi.org/10.3390/f3040923

Eriksson L, Nordlund AM, Olsson O, Westin K. Recreation in Different Forest Settings: A Scene Preference Study. Forests. 2012; 3(4):923-943. https://doi.org/10.3390/f3040923

Chicago/Turabian StyleEriksson, Louise, Annika M. Nordlund, Olof Olsson, and Kerstin Westin. 2012. "Recreation in Different Forest Settings: A Scene Preference Study" Forests 3, no. 4: 923-943. https://doi.org/10.3390/f3040923

APA StyleEriksson, L., Nordlund, A. M., Olsson, O., & Westin, K. (2012). Recreation in Different Forest Settings: A Scene Preference Study. Forests, 3(4), 923-943. https://doi.org/10.3390/f3040923