Stakeholder Participation and Multi-Actor Collaboration in Model Forest Governance: Insights from the Bucak Model Forest, Türkiye

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

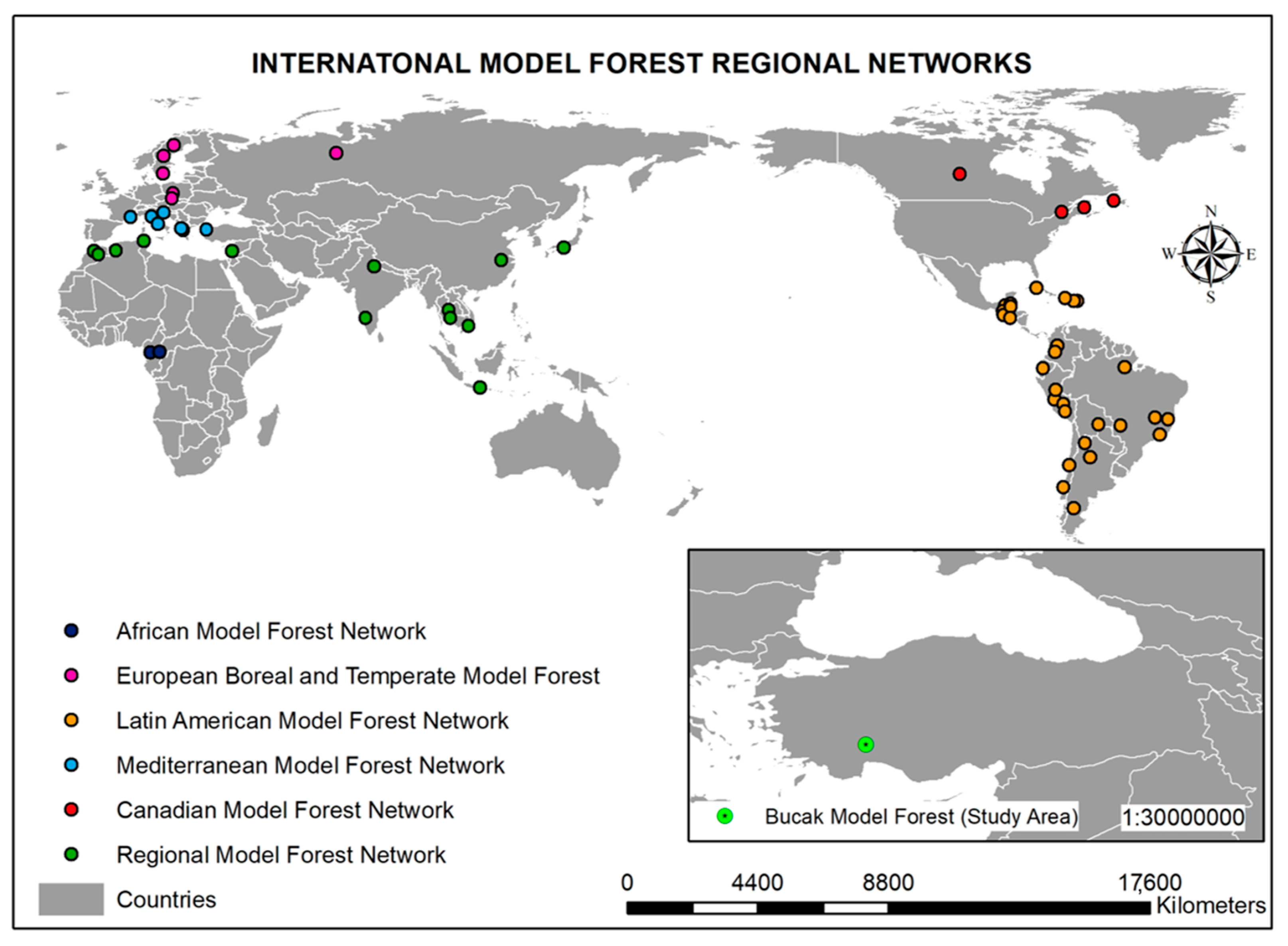

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Study Data and Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Determinants of Willingness to Contribute to the BMF Initiative

3.3. Relationships Between Demographic Characteristics and Model Forest Participation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMF | Bucak Model Forest |

| FSC | Forest Stewardship Council |

| OGM | General Directorate of Forestry |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SFM | Sustainable Forest Management |

| IMFN | International Model Forest Network |

| YMF | Yalova Model Forest |

References

- Klenk, N.L.; Reed, M.G.; Lidestav, G.; Carlsson, J. Models of representation and participation in Model Forests: Dilemmas and implications for networked forms of environmental governance involving indigenous people. Environ. Policy Gov. 2013, 23, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarino, I.D.M.; Fernandes, M.E.D.S.T. A bibliometric review of stakeholders’ participation in sustainable forest management. Can. J. For. Res. 2023, 54, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbakidze, M.; Angelstam, P.; Sandström, C.; Axelsson, R. Multi-stakeholder collaboration in Russian and Swedish Model Forest initiatives: Adaptive governance toward sustainable forest management? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, H.; Droste, N.; Brady, M. Modelling forests as social-ecological systems: A systematic comparison of agent-based approaches. Environ. Model. Softw. 2024, 175, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenholm, E. The İnfluence of Stakeholder Participation on the Legitimacy of Municipal Environmental Governance: A Qualitative Case Study of Stakeholder Participation in Kristianstad Vattenrike Biosphere Reserve. Master’s Thesis, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, 2024; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Wel, K.; van de Mortel, M.; van de Grift, L.; Akerboom, S. How to make stakeholder participation work? Constructing legitimacy in environmental policymaking. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2025, 27, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolunay, A.; Türkoglu, T.; Elbakidze, M.; Angelstam, P. Determination of the Support Level of Local Organizations in a Model Forest Initiative: Do Local Stakeholders Have Willingness to Be Involved in the Model Forest Development? Sustainability 2014, 6, 7181–7196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelstam, P.; Elbakidze, M.; Axelsson, R.; Khoroshev, A.; Pedroli, B.; Tysiachniouk, M.; Zabubenin, E. Model forests in Russia as landscape approach: Demonstration projects or initiatives for learning towards sustainable forest management? For. Policy Econ. 2019, 101, 96–110. [Google Scholar]

- Luyet, V.; Schlaepfer, R.; Parlange, M.B.; Buttler, A. A framework to implement stakeholder participation in environmental projects. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 111, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Barreira, A.P.; Loures, L.; Antunes, D.; Panagopoulos, T. Stakeholders’ engagement on nature-based solutions: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelyukh, O.; Lavnyy, V.; Paletto, A.; Troxler, D. Stakeholder analysis in sustainable forest management: An application in the Yavoriv region (Ukraine). For. Policy Econ. 2021, 131, 102561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, B.D.; Larson, A.M.; Barletti, J.P.S.; ElDidi, H.; Catacutan, D.; Flintan, F.; Suhardiman, D.; Falk, T.; Meinzen-Dick, R. Multistakeholder platforms for natural resource governance: Lessons from eight landscape-level cases. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnell, B.; de Camino, R.; Diaw, C.; Johnston, M.; Majewski, P.; Montejo, I.; Segur, M.; Svensson, J. From Rio to Rwanda: Impacts of the IMFN over the past 20 years. For. Chron. 2012, 88, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvenegaard, G.T.; Carr, S.; Clark, K.; Dunn, P.; Olexson, T. Promoting sustainable forest management among stakeholders in the prince albert model forest, Canada. Conserv. Soc. 2015, 13, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Sjölander-Lindqvist, A.; Dressel, S.; Ericsson, G.; Sandström, C. Expectations about voluntary efforts in collaborative governance and the fit with perceived prerequisites of intrinsic motivation in Sweden’s ecosystem-based moose management system. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, 20. [Google Scholar]

- IMFN (International Model Forest Network). Research Shows Model Forest Effectively Connects Stakeholders. Available online: https://imfn.net (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Axelsson, R.; Ljung, M.; Blicharska, M.; Frisk, M.; Henningsson, M.; Mikusiński, G.; Folkeson, L.; Göransson, G.; Jönsson-Ekström, S.; Sjölund, A.; et al. The challenge of transdisciplinary research: A case study of learning by evaluation for sustainable transport infrastructures. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekiroğlu, S.; Özdemir, M.; Özyürek, E.; Arslan, A. Opportunities to enhance contribution of model forests in the sustainable forest resources management (example from Yalova Model Forest). J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 181, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbakidze, M.; Angelstam, P.; Axelsson, R. Sustainable forest management as an approach to regional development in the Russian Federation: State and trends in Kovdozersky Model Forest in the Barents region. Scand. J. For. Res. 2007, 22, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichiforel, L.; Buliga, B.; Palaghianu, C. Two decades of stakeholder voices: Exploring engagement in Romania’s FSC forest management certification. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 475, 143718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başak, E.; Cetin, N.I.; Vatandaşlar, C.; Pamukcu-Albers, P.; Karabulut, A.A.; Çağlayan, S.D.; Besen, T.; Erpul, G.; Balkız, Ö.; Avcıoğlu Çokçalışkan, B.; et al. Ecosystem services studies in Turkey: A national-scale review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 844, 157068. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Youn, Y.C. Relevance of cultural ecosystem services in nurturing ecological identity values that support restoration and conservation efforts. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 505, 119920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaro, S.; Delabre, I.; Marshall, F. Cultural ecosystem services and opportunities for inclusive and effective nature-based solutions. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 230, 108525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andong, S.; Dupuits, E.; Enriquez, D.; Melchiade, L.; Ongolo, S.; Robles, Á.S. Unshaping Model Forests in the Global South: Trans-Local Politics and Community Forestry Knowledge Circulation in Ecuador and Cameroon. Int. J. Commons 2025, 19, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ginkel, J.R. Significance Tests and Estimates for R2 for Multiple Regression in Multiply Imputed Datasets: A Cautionary Note on Earlier Findings, and Alternative Solutions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2019, 54, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, W. Social Statistics Using Microcase; Nelson Hall Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992; ISBN 10 0922914273. [Google Scholar]

- BMF. Bucak Model Forest Strategic Plan 2018–2022; BMF: Bucak, Türkiye, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wallin, I.; Carlsson, J.; Hansen, H.P. Envisioning future forested landscapes in Sweden–Revealing local-national discrepancies through participatory action research. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 73, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, T.; Murtinho, F.; Wolff, H. The impact of payments for environmental services on communal lands: An analysis of the factors driving household land-use behavior in Ecuador. World Dev. 2017, 93, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogoi, J.; Obonyo, E.; Ongugo, P.; Oeba, V.; Mwangi, E. Communities, property rights and forest decentralisation in Kenya: Early lessons from participatory forestry management. Conserv. Soc. 2012, 10, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, J.; Alavalapati, J.; Kerr, J.; Mercer, E. Agency perspectives on transition to participatory forest management: A case study from Tamil Nadu, India. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekiroğlu, S.; Özdemir, M.; Özyürek, E.; Çakır, G. Significance of model forest stakeholders in the management of sustainable forest resources: The case of Yalova model forest, Turkey. Forestist 2024, 74, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.P.; Maraseni, T.N.; Apan, A.; Pokhrel, S.; Zhang, H. Lessons from a participatory forest restoration program on socio-ecological and environmental aspects in Nepal. Trees For. People 2025, 20, 100854. [Google Scholar]

- Angelstam, P.; Andersson, K.; Axelsson, R.; Elbakidze, M.; Jonsson, B.G.; Roberge, J.M. Protecting forest areas for biodiversity in Sweden 1991–2010: The policy implementation process and outcomes on the ground. Silva Fenn. 2011, 45, 1111–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbakidze, M.; Angelstam, P.; Axelsson, R. Stakeholder identification and analysis for adaptive governance in the Kovdozersky Model Forest, Russian Federation. For. Chron. 2012, 88, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, C.; Carrera, E.; Imbach, A.; Villalobos, R.; Durán, L. Impacts and Lessons Learned from Participatory Landscape Management Platforms: The Case of Latin American Model Forests. 2021. Available online: https://imfn.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/RLABM-Impact-report-2020-FINAL-ENG.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Calder, I.R. Forests and water—Ensuring forest benefits outweigh water costs. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 251, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ombogoh, D.B.; Mwangi, E.; Larson, A.M. Community participation in forest and water management planning in Kenya: Challenges and opportunities. For. Trees Livelihoods 2022, 31, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Herr, A. Hunting and fishing tourism. In Wildlife Tourism: Impacts, Management and Planning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; Chapter 4; pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lhoest, S.; Vermeulen, C.; Fayolle, A.; Jamar, P.; Hette, S.; Nkodo, A.; Maréchal, K.; Dufrêne, M.; Meyfroidt, P. Quantifying the Use of Forest Ecosystem Services by Local Populations in Southeastern Cameroon. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, M. Evaluation of Yalova’s Participation in the International Model Forest Network in terms of Turkish Forestry. In National Mediterranean Forest and Environment Symposium Proceedings Book; KSÜ Faculty of Forestry: Kahramanmaraş, Türkiye, 2011; pp. 1367–1376. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, P.; Elbakidze, M.; Angelstam, P. Stakeholders’ perceptions on ecosystem services in Östergötland’s (Sweden) threatened oak wood-pasture landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 158, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, D. Mining conflicts and transformative politics: A comparison of Intag (Ecuador) and Mount Ida (Turkey) environmental struggles. Geoforum 2017, 84, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, Ç.; Özdemir, S.; Perkumienė, D.; Aleinikovas, M.; Šilinskas, B.; Škėma, M. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Avian Species Richness Across Climatic Regions. Diversity 2025, 17, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, C.; Huang, J.; Li, T.; Lei, J. Forests and Forestry in Support of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Bibliometric Analysis. Forests 2022, 13, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelstam, P.; Andersson, K.; Annerstedt, M.; Axelsson, R.; Elbakidze, M.; Garrido, P.; Grahn, P.; Johnsson, K.I.; Pedersen, S.; Schlyter, P.; et al. Solving problems in social–ecological systems: Definition, practice and barriers of transdisciplinary research. Ambio 2013, 42, 254–265. [Google Scholar]

- Secco, L.; Pettenella, D. Participatory processes in forest management: The Italian experience in defining and implementing forest certification schemes. Schweiz. Z. Forstwes. 2006, 157, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 649 | 57 |

| Female | 485 | 43 | |

| Age | 19–30 | 513 | 45 |

| 31 and above | 621 | 55 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 475 | 42 |

| Married | 659 | 58 | |

| Education Level | Literate | 33 | 3 |

| Primary School | 142 | 13 | |

| Middle School | 287 | 25 | |

| High School | 412 | 36 | |

| Associate Degree | 172 | 15 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 88 | 8 | |

| Occupation | Unemployed | 111 | 10 |

| Daily Worker | 53 | 5 | |

| Farmer | 153 | 13 | |

| Retired | 59 | 5 | |

| Student | 175 | 15 | |

| Housewife | 200 | 18 | |

| Worker | 184 | 16 | |

| Public Official | 61 | 5 | |

| Trader | 75 | 7 | |

| Other | 63 | 6 | |

| Place of Residence | Village | 352 | 31 |

| Town | 131 | 12 | |

| District Center | 651 | 57 | |

| Duration of Residence | Native-born | 719 | 64 |

| 1–5 years | 184 | 16 | |

| 6–10 years | 231 | 20 |

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMF Awareness | Yes | 511 | 45 |

| No | 623 | 55 | |

| Willingness to Contribute to BMF | Yes | 674 | 60 |

| No | 230 | 20 | |

| Undecided | 230 | 20 |

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trust in the Forestry Organization | Yes | 756 | 67 |

| No | 137 | 12 | |

| Undecided | 241 | 21 | |

| Perceiving the Organization as Political | Yes | 397 | 35 |

| No | 286 | 25 | |

| Undecided | 451 | 40 | |

| Comfort in Visiting the Organization | Always can | 633 | 56 |

| Can | 344 | 30 | |

| Undecided | 85 | 8 | |

| Cannot easily | 48 | 4 | |

| Cannot | 24 | 2 | |

| Comfort Expressing Opinions to Forest Officers | Always can | 515 | 45 |

| Can | 415 | 37 | |

| Undecided | 102 | 9 | |

| Cannot easily | 57 | 5 | |

| Cannot | 45 | 4 |

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Support for Mining Operations in Forest Areas | Yes | 446 | 39 |

| No | 447 | 40 | |

| Undecided | 241 | 21 | |

| Support for Ecotourism Investments | Yes | 798 | 70 |

| No | 158 | 14 | |

| Undecided | 178 | 16 | |

| Approving Forests as Waste Disposal Areas | Yes | 288 | 25 |

| No | 846 | 75 | |

| Preferences Regarding the Utilization of Forest Resources | Waged forest work | 169 | 5 |

| Collecting plants/mushrooms for sale | 137 | 4 | |

| Collecting plants/mushrooms for food | 337 | 11 | |

| Recreation | 953 | 30 | |

| Fishing | 220 | 7 | |

| Drinking water supply | 517 | 16 | |

| Firewood collection | 421 | 13 | |

| Use of forest soil | 175 | 6 | |

| Hunting | 196 | 6 | |

| Beekeeping | 68 | 2 |

| Activity | Always Can (%) | Can (%) | Undecided (%) | Cannot Easily (%) | Cannot (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporting illegal logging | 46 | 36 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| Volunteering to fight forest fires | 63 | 23 | 4 | 7 | 3 |

| Removing harmful animals from forests | 32 | 27 | 16 | 16 | 9 |

| Warning people who may harm forests | 48 | 33 | 5 | 10 | 4 |

| Educating children about forests | 67 | 20 | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| Planting tree saplings | 59 | 28 | 6 | 5 | 2 |

| Joining forestry trainings | 31 | 32 | 18 | 14 | 5 |

| Following forestry developments | 22 | 25 | 16 | 24 | 13 |

| Volunteering for forests without remuneration | 31 | 33 | 13 | 6 | 17 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefts | t | Sig. | Collinearity Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 1.120 | 0.049 | 22.667 | 0.000 | |||

| Finding ecotourism positive | 0.336 | 0.030 | 0.314 | 11.133 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 2 | (Constant) | 0.528 | 0.080 | 6.631 | 0.000 | |||

| Finding ecotourism positive | 0.307 | 0.029 | 0.287 | 10.476 | 0.000 | 0.988 | 1.012 | |

| Awareness of the BMF project | 0.409 | 0.044 | 0.254 | 9.273 | 0.000 | 0.988 | 1.012 | |

| 3 | (Constant) | 0.334 | 0.082 | 4.094 | 0.000 | |||

| Finding ecotourism positive | 0.261 | 0.029 | 0.244 | 8.925 | 0.000 | 0.946 | 1.057 | |

| Awareness of the BMF project | 0.391 | 0.043 | 0.242 | 9.060 | 0.000 | 0.985 | 1.015 | |

| Willingness to work in forestry without financial compensation | 0.118 | 0.015 | 0.208 | 7.649 | 0.000 | 0.951 | 1.051 | |

| 4 | (Constant) | 0.170 | 0.092 | 1.859 | 0.063 | |||

| Positive perception of ecotourism investments | 0.258 | 0.029 | 0.241 | 8.899 | 0.000 | 0.946 | 1.057 | |

| Awareness of the BMF project | 0.379 | 0.043 | 0.235 | 8.807 | 0.000 | 0.980 | 1.021 | |

| Willingness to work in forestry without financial compensation | 0.114 | 0.015 | 0.202 | 7.460 | 0.000 | 0.948 | 1.055 | |

| Seeing the forestry institution as a political structure | 0.095 | 0.025 | 0.102 | 3.856 | 0.000 | 0.989 | 1.011 | |

| 5 | (Constant) | 0.301 | 0.102 | 2.961 | 0.003 | |||

| Finding ecotourism positive | 0.269 | 0.029 | 0.251 | 9.217 | 0.000 | 0.932 | 1.073 | |

| Awareness of the BMF project | 0.407 | 0.044 | 0.252 | 9.264 | 0.000 | 0.933 | 1.071 | |

| Willingness to work in forestry without financial compensation | 0.111 | 0.015 | 0.197 | 7.283 | 0.000 | 0.944 | 1.059 | |

| Seeing the forestry institution as a political structure | 0.097 | 0.025 | 0.104 | 3.937 | 0.000 | 0.989 | 1.012 | |

| Gender | −0.130 | 0.044 | −0.080 | −2.937 | 0.003 | 0.932 | 1.072 | |

| 6 | (Constant) | 0.277 | 0.101 | 2.734 | 0.006 | |||

| Finding ecotourism positive | 0.263 | 0.029 | 0.246 | 9.030 | 0.000 | 0.928 | 1.078 | |

| Awareness of the BMF project | 0.381 | 0.045 | 0.236 | 8.567 | 0.000 | 0.901 | 1.109 | |

| Willingness to work in forestry without financial compensation | 0.109 | 0.015 | 0.193 | 7.149 | 0.000 | 0.942 | 1.061 | |

| Seeing the forestry institution as a political structure | 0.081 | 0.025 | 0.087 | 3.220 | 0.001 | 0.945 | 1.058 | |

| Gender | −0.144 | 0.044 | −0.089 | −3.246 | 0.001 | 0.923 | 1.084 | |

| Trust in the forestry organization | 0.084 | 0.027 | 0.086 | 3.080 | 0.002 | 0.884 | 1.131 | |

| 7 | (Constant) | 0.189 | 0.109 | 1.727 | 0.084 | |||

| Finding ecotourism positive | 0.261 | 0.029 | 0.243 | 8.960 | 0.000 | 0.927 | 1.079 | |

| Awareness of the BMF project | 0.382 | 0.044 | 0.237 | 8.595 | 0.000 | 0.901 | 1.110 | |

| Willingness to work in forestry without financial compensation | 0.111 | 0.015 | 0.197 | 7.297 | 0.000 | 0.937 | 1.067 | |

| Seeing the forestry institution as a political structure | 0.074 | 0.025 | 0.080 | 2.959 | 0.003 | 0.933 | 1.072 | |

| Gender | −0.150 | 0.044 | −0.092 | −3.385 | 0.001 | 0.919 | 1.088 | |

| Trust in the forestry organization | 0.081 | 0.027 | 0.083 | 2.983 | 0.003 | 0.882 | 1.134 | |

| Positive perception of mining operations | 0.061 | 0.028 | 0.058 | 2.169 | 0.030 | 0.971 | 1.030 | |

| Demographic Variables | Gender | Age | Marital Status | Educational Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables Related to Forestry and the BMF | Pearson Chi-Square Value | Asymp. Sig. (2-Sided) | Pearson Chi-Square Value | Asymp. Sig. (2-Sided) | Pearson Chi-Square Value | Asymp. Sig. (2-Sided) | Pearson Chi-Square Value | Asymp. Sig. (2-Sided) | |

| Awareness of the BMF | 58.771 a | 0.000 ** | 59.682 a | 0.000 ** | 57.629 a | 0.000 ** | 35.655 a | 0.000 ** | |

| Willingness to Contribute to the BMF | 2.990 a | 0.224 | 14.473 a | 0.025 ** | 18.534 a | 0.001 ** | 6.003 a | 0.815 | |

| Trust in the Forestry Organization | 28.384 a | 0.000 ** | 10.341 a | 0.111 | 22.670 a | 0.000 ** | 10.294 a | 0.415 | |

| Perception of the Forestry Organization as a Political Institution | 12.928 a | 0.002 ** | 6.088 a | 0.413 | 2.560 a | 0.634 | 22.174 a | 0.014 ** | |

| Positive Perception of Mining Activities | 11.346 a | 0.003 | 12.359 a | 0.054 | 5.258 a | 0.262 | 33.730 a | 0.000 ** | |

| Finding ecotourism positive | 20.724 a | 0.000 ** | 8.673 a | 0.193 | 5.307 a | 0.257 | 20.424 a | 0.025 | |

| Occasionally Disposing of Waste in Forest Areas | 4.378 a | 0.036 ** | 15.991 a | 0.001 ** | 3.486 a | 0.175 | 27.134 a | 0.000 ** | |

| Willingness to Visit the Forestry Organization Without Hesitation | 93.213 a | 0.000 ** | 19.689 a | 0.073 | 12.276 a | 0.139 | 36.764 a | 0.012 ** | |

| Willingness to Express Opinions Freely to Forestry Officials | 66.006 a | 0.000 ** | 13.027 a | 0.367 | 5.807 a | 0.669 | 29.890 a | 0.072 | |

| Reporting Illegal Logging in Forests | 19.669 a | 0.001 ** | 12.814 a | 0.383 | 16.213 a | 0.039 ** | 49.154 a | 0.000 ** | |

| Volunteering to Extinguish Forest Fires | 16.174 a | 0.003 ** | 36.315 a | 0.000 ** | 6.298 a | 0.614 | 36.086 a | 0.015 ** | |

| Driving Away Animals That Damage Forests | 93.472 a | 0.000 ** | 41.944 a | 0.000 ** | 26.787 a | 0.001 ** | 59.325 a | 0.000 ** | |

| Warning People Who May Harm Forests | 31.669 a | 0.000 ** | 36.217 a | 0.000 ** | 34.816 a | 0.000 ** | 73.183 a | 0.000 ** | |

| Educating Children About Forests | 9.720 a | 0.045 ** | 8.205 a | 0.769 | 7.939 a | 0.439 | 39.626 a | 0.006 ** | |

| Planting Tree Saplings Found or Received | 13.744 a | 0.008 ** | 22.140 a | 0.036 ** | 20.233 a | 0.009 ** | 57.956 a | 0.000 ** | |

| Volunteering to Attend Forestry-Related Training | 7.286 a | 0.122 | 30.878 a | 0.002 ** | 40.938 a | 0.000 ** | 68.334 a | 0.000 ** | |

| Following Developments in Forestry | 33.158 a | 0.000 ** | 55.656 a | 0.000 ** | 73.185 a | 0.000 ** | 74.871 a | 0.000 ** | |

| Following Developments in Forestry | 16.211 a | 0.003 ** | 31.280 a | 0.002 ** | 14.734 a | 0.065 | 26.235 a | 0.158 | |

| Age | Total | Marital Status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–30 | >31 | Single | Married | Total | ||||

| Willingness to Contribute to the BMF | Yes | Count | 283 | 391 | 674 | 255 | 419 | 674 |

| % within Age and Marial Status | 55.2% | 63% | 59.4% | 53.7% | 63.6% | 59.4% | ||

| No | Count | 105 | 125 | 230 | 98 | 132 | 230 | |

| % within Age and Marial Status | 20.5% | 20.1% | 20.3% | 20.6% | 20% | 20.3% | ||

| Undecided | Count | 125 | 105 | 230 | 122 | 108 | 230 | |

| % within Age and Marial Status | 24.4% | 16.9% | 20.3% | 25.7% | 16.4% | 20.3% | ||

| Total | Count | 513 | 621 | 1134 | 475 | 659 | 1134 | |

| % within Age and Marial Status | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Turkoglu, T.; Škėma, M.; Buyuksakalli, H.; Tolunay, A.; Uyar, Ç.; Bekiroğlu, S.; Perkumienė, D.; Aleinikovas, M.; Beriozovas, O. Stakeholder Participation and Multi-Actor Collaboration in Model Forest Governance: Insights from the Bucak Model Forest, Türkiye. Forests 2026, 17, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010004

Turkoglu T, Škėma M, Buyuksakalli H, Tolunay A, Uyar Ç, Bekiroğlu S, Perkumienė D, Aleinikovas M, Beriozovas O. Stakeholder Participation and Multi-Actor Collaboration in Model Forest Governance: Insights from the Bucak Model Forest, Türkiye. Forests. 2026; 17(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleTurkoglu, Turkay, Mindaugas Škėma, Halit Buyuksakalli, Ahmet Tolunay, Çağdan Uyar, Sultan Bekiroğlu, Dalia Perkumienė, Marius Aleinikovas, and Olegas Beriozovas. 2026. "Stakeholder Participation and Multi-Actor Collaboration in Model Forest Governance: Insights from the Bucak Model Forest, Türkiye" Forests 17, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010004

APA StyleTurkoglu, T., Škėma, M., Buyuksakalli, H., Tolunay, A., Uyar, Ç., Bekiroğlu, S., Perkumienė, D., Aleinikovas, M., & Beriozovas, O. (2026). Stakeholder Participation and Multi-Actor Collaboration in Model Forest Governance: Insights from the Bucak Model Forest, Türkiye. Forests, 17(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010004