Early Post-Germination Physiological Traits of Oak Species Under Various Environmental Conditions in Oak Forests

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seed Collecting

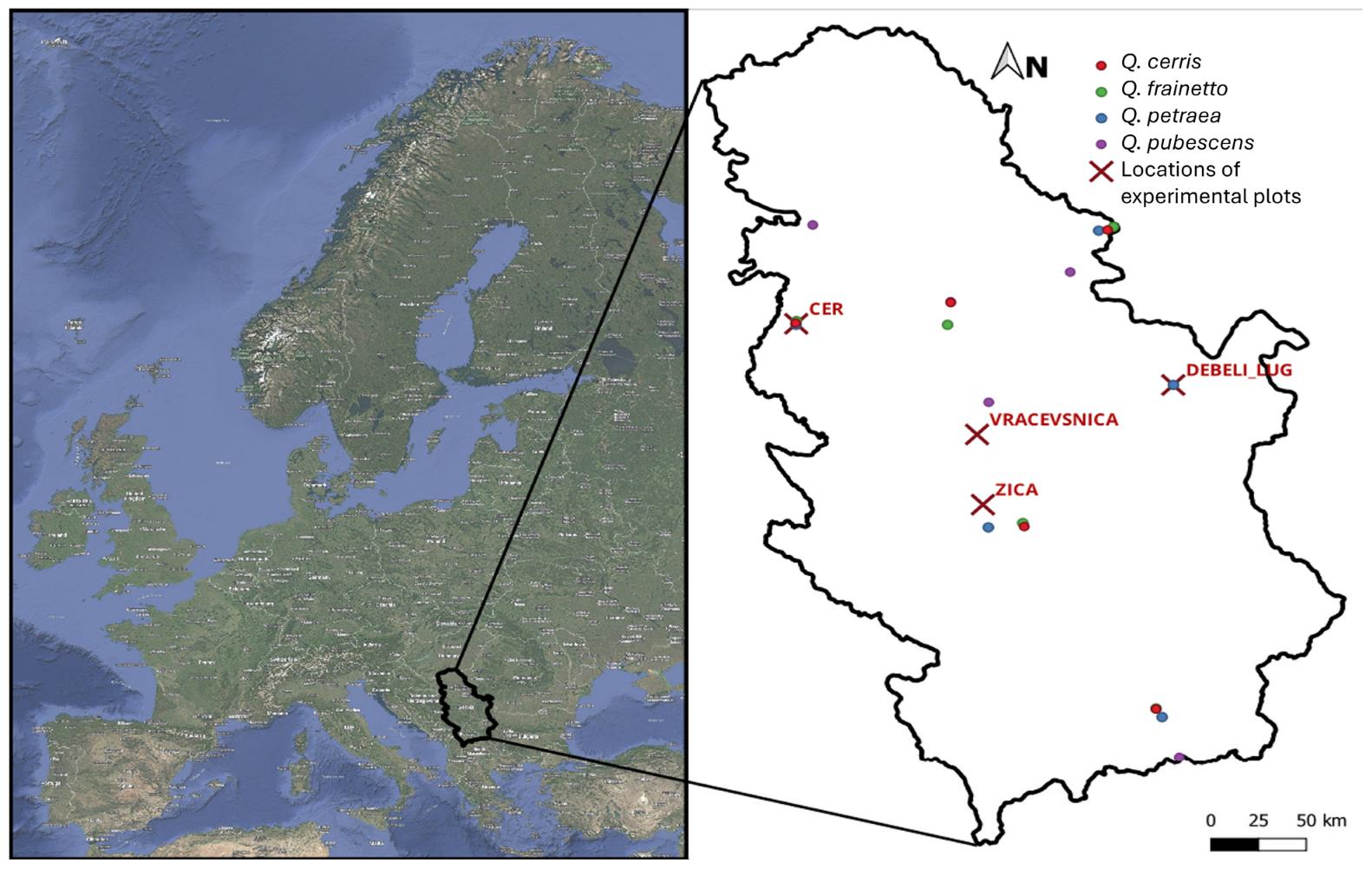

2.2. Experiment Plots

2.3. Applied Method—Direct Seeding

2.4. Morphological and Physiological Measurements

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Conditions

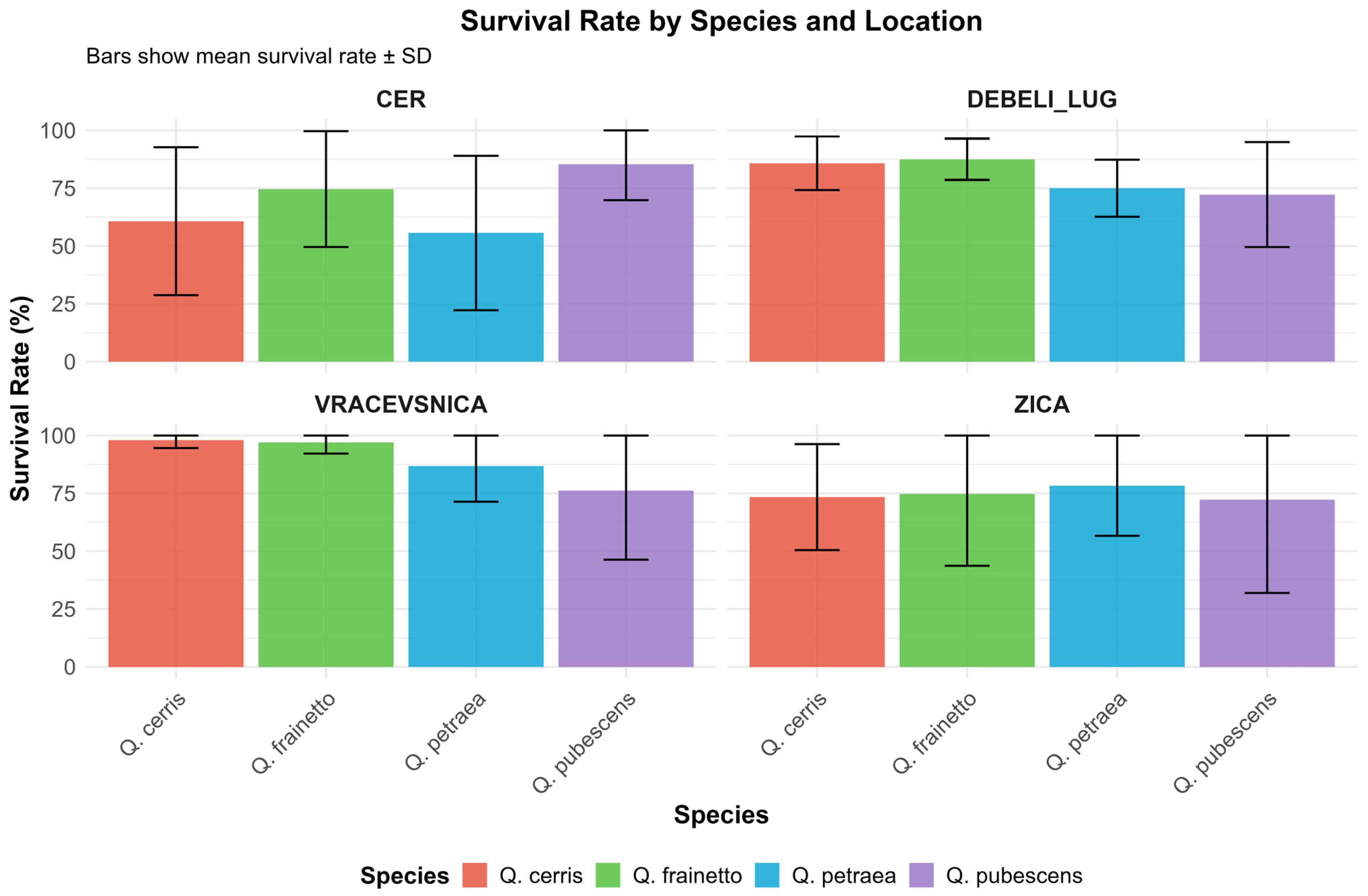

3.2. Survival

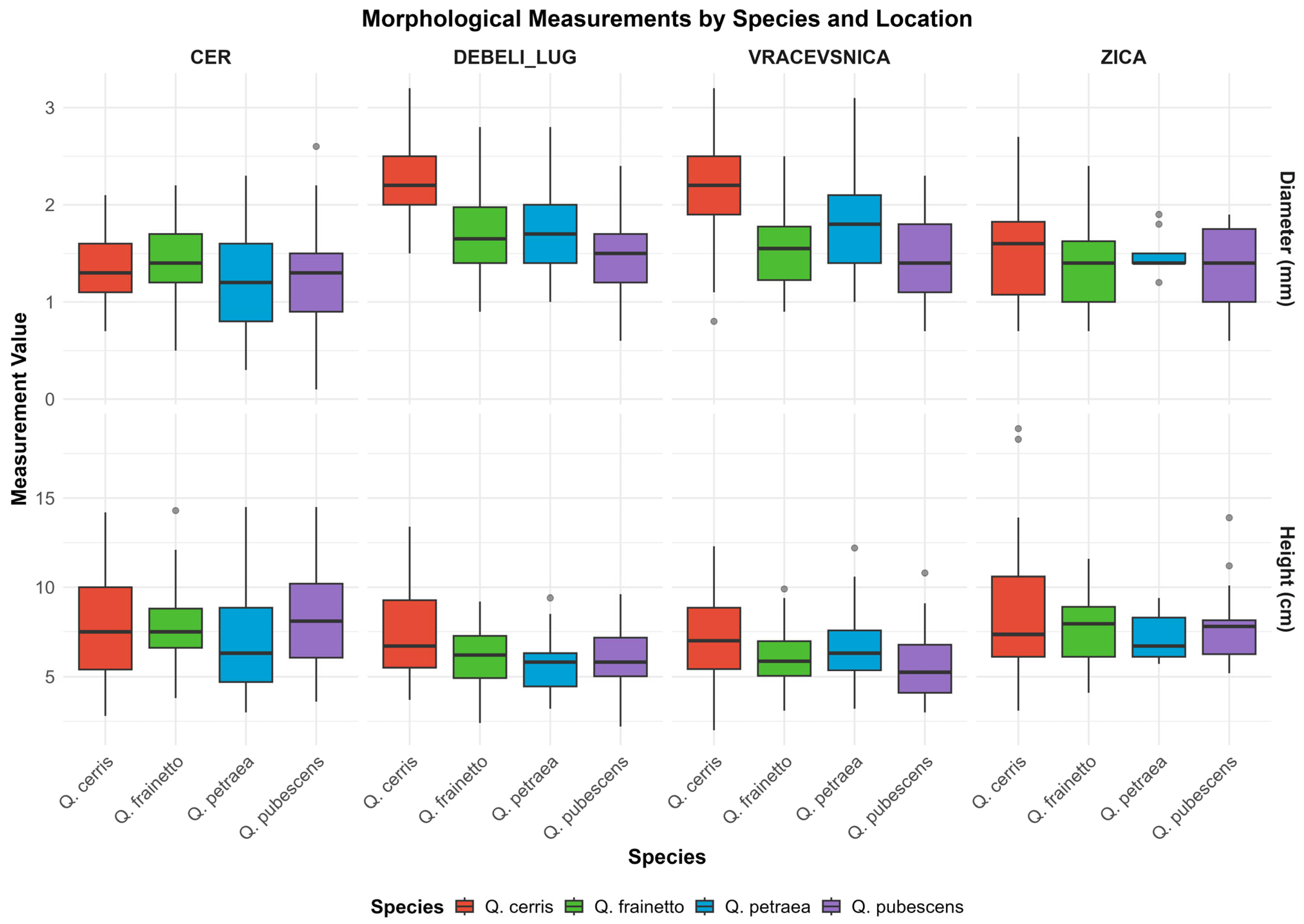

3.3. Morphology

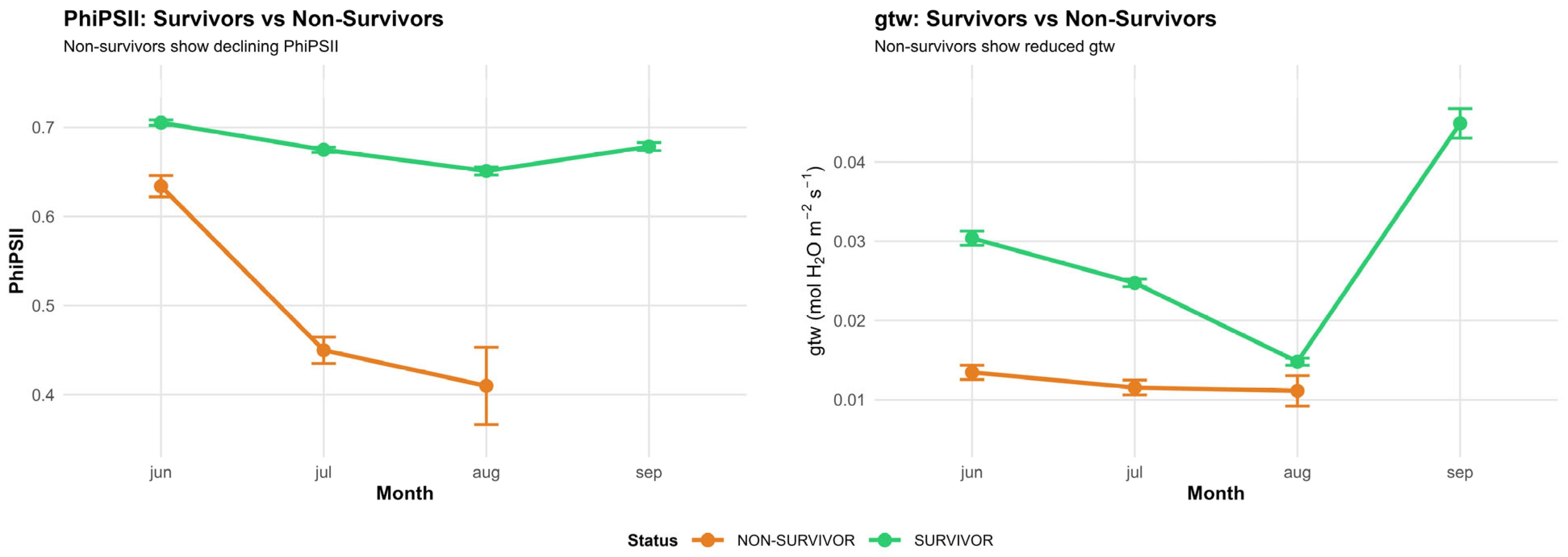

3.4. Physiology

4. Discussion

4.1. Habitat Effects on Seedling Physiology (H1)

4.2. Differences in Physiological Responses Among Oak Species (H2)

4.3. Morphological Parameters

4.4. Physiological Predictors of Survival (H3)

4.5. Practical Implications for Oak Restoration

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kremer, A. Microevolution of European Temperate Oaks in Response to Environmental Changes. C. R. Biol. 2016, 339, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratu, I.; Dinca, L.; Constandache, C.; Murariu, G. Resilience and Decline: The Impact of Climatic Variability on Temperate Oak Forests. Climate 2025, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, L.; Nola, P.; Serre-Bachet, F. Deciduous Quercus in the Mediterranean Region: Tree-Ring/Climate Relationships. New Phytol. 1994, 126, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea-Izquierdo, G.; Fonti, P.; Cherubini, P.; Martín-Benito, D.; Chaar, H.; Cañellas, I. Xylem Hydraulic Adjustment and Growth Response of Quercus canariensis Willd. to Climatic Variability. Tree Physiol. 2012, 32, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossner, M.; Schall, P.; Ammer, C.; Ammer, U.; Engel, K.; Schubert, H.; Simo, U.; Utschick, H.; Weisser, W.W. Forest-management intensity measures as alternative to stand properties for quantifying effects on biodiversity. Ecosphere 2014, 5, art113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tăut, I.; Bora, F.D.; Rebrean, F.A.; Moldovan, C.M.; Varga, M.I.; Șimonca, V.; Colișar, A.; Bartha, S.; Timofte, C.S.; Sestraș, P. Climate-Driven Decline of Oak Forests: Integrating Ecological Indicators and Sustainable Management Strategies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjevac, B.; Krstić, M.; Babić, V.; Govedar, Z. Regeneration Dynamics and Development of Seedlings in Sessile Oak Forests in Relation to Light Availability and Competing Vegetation. Forests 2021, 12, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.K.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Ueno, S.; de Lafontaine, G. Contrasted Patterns of Local Adaptation to Climate Change Across the Range of an Evergreen Oak, Quercus aquifolioides. Evol. Appl. 2020, 13, 2377–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, J.R.; Jouzel, J.; Raynaud, D.; Barkov, N.I.; Barnola, J.-M.; Basile, I.; Bender, M.; Chappellaz, J.; Davis, M.; Delaygue, G.; et al. Climate and Atmospheric History of the Past 420,000 Years from the Vostok Ice Core, Antarctica. Nature 1999, 399, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstić, M.; Kanjevac, B.; Babić, V. Effects of Extremely High Temperatures on Some Growth Parameters of Sessile Oak (Quercus petraea) Seedlings in Northeastern Serbia. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2018, 70, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mölder, A.; Sennhenn-Reulen, H.; Fischer, C.; Rumpf, H.; Schönfelder, E.; Stockmann, J.; Nagel, R.-V. Success Factors for High-quality Oak Forest Regeneration (Quercus robur, Q. petraea). For. Ecosyst. 2019, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinya, F.; Kovács, B.; Aszalós, R.; Tóth, B.; Csépányi, P.; Németh, C.; Ódor, P. Initial Regeneration Success of Tree Species After Different Forestry Treatments in a Sessile Oak–Hornbeam Forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 459, 117810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjevac, B.; Ljubičić, J.; Kerkez Janković, I.; Mijatović, L.; Devetaković, J. Regeneration of Hilly-mountainous Oak Forests in Serbia—Past Experiences and Future Perspectives. Reforesta 2024, 18, 34–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, A.; Enescu, C.M.; Houston Durrant, T.; de Rigo, D.; Caudullo, G. Quercus frainetto in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-92-79-52833-0. [Google Scholar]

- De Rigo, D.; Enescu, C.M.; Houston Durrant, T.; Caudullo, G. Quercus cerris in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-92-79-52833-0. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, E.; Caudullo, G.; Oliveira, S.; de Rigo, D. Quercus robur and Quercus petraea in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 160–163. ISBN 978-92-79-52833-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pasta, S.; de Rigo, D.; Caudullo, G. Quercus pubescens in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-92-79-52833-0. [Google Scholar]

- Quero, J.L.; Villar, R.; Marañón, T.; Zamora, R. Interactions of drought and shade effects on seedlings of four Quercus species: Physiological and structural leaf responses. New Phytol. 2006, 170, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemán, J.; Chirino, E.; Espelta, J.M.; Jacobs, D.F.; Martín-Gómez, P.; Navarro-Cerrillo, R.; Oilet, J.A.; Vilagrosa, A.; Villar-Salvador, P.; Gil-Pelegrín, E. Physiological Keys for Natural and Artificial Regeneration of Oaks. In Oaks Physiological Ecology. Exploring the Functional Diversity of Genus Quercus L.; Gil-Pelegrín, E., Peguero-Pina, J., Sancho-Knapik, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 7, ISBN 978-3-319-69099-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.; Baskin, J. Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Villar-Salvador, P.; Heredia, N.; Millard, P. Remobilization of acorn nitrogen for seedling growth in holm oak (Quercus ilex) cultivated with contrasting nutrient availability. Tree Physiol. 2009, 30, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverkus, A.B.; Medina, M.; Lázaro-González, A.; Levy, L.; Lorente-Casalini, O.; Reyes Martín, M.P. Drivers of seedling emergence and early growth of 12 European oak species: Results from a cross-continental experiment. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 599, 123223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, A.S.; Duwyn, A.; Jones, N.T. Consumer-based limitations drive oak recruitment failure. Ecology 2010, 91, 2092–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Bartlow, A.W.; Curtis, R.; Agosta, S.J.; Steele, M.A. Responses of seedling growth and survival to post-germination cotyledon removal: An investigation among seven oak species. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 1817–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrosavljevic, J.; Devetaković, J.; Kanjevac, B. The bigger the tree the better the seed—Effect of Sessile oak tree diameter on acorn size, insect predation, and germination. Reforesta 2022, 14, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.M.; Gausling, T. Morphological and physiological responses of oak seedlings (Quercus petraea and Q. robur) to moderate drought. Ann. For. Sci. 2000, 57, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, E.; Cochard, H.; Deluigi, J.; Didion-Gency, M.; Martin-StPaul, N.; Morcillo, L.; Valladares, F.; Vilagrosa, A.; Grossiord, C. Interactions between beech and oak seedlings can modify the effects of hotter droughts and the onset of hydraulic failure. New Phytol. 2024, 241, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rellstab, C.; Zoller, S.; Walthert, L.; Lesur, I.; Pluess, A.R.; Graf, R.; Bodénès, C.; Sperisen, C.; Kremer, A.; Gugerli, F. Signatures of local adaptation in candidate genes of oaks (Quercus spp.) with respect to present and future climatic conditions. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 5907–5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, F.; Jalali, S.G.; Sohrabi, H.; Shirvany, A. Physiological responses of seedlings of different Quercus castaneifolia C.A. Mey. provenances to heterogeneous light environments. J. For. Sci. 2016, 62, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-R.; Ning, X.; Zheng, S.-S.; Li, Y.; Lu, Z.-J.; Meng, H.-H.; Ge, B.-J.; Kozlowski, G.; Yan, M.-X.; Song, Y.-G. Genomic insights into ecological adaptation of oaks revealed by phylogenomic analysis of multiple species. Plant Divers. 2025, 47, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosenko, T.; Schroeder, H.; Zimmer, I.; Buegger, F.; Orgel, F.; Burau, I.; Padmanaban, P.B.S.; Ghirardo, A.; Bracker, R.; Kersten, B.; et al. Patterns of adaptation to drought in Quercus robur populations in Central European temperate forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Provost, G.; Gerardin, T.; Plomion, C.; Brendel, O. Molecular plasticity to soil water deficit differs between sessile oak (Quercus petraea) high- and low-water-use-efficiency genotypes. Tree Physiol. 2022, 42, 2546–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebert, M.; Vuksanović, V.; Stefels, J.; Bojović, M.; Horák, R.; Kostić, S.; Kovačević, B.; Orlović, S.; Neri, L.; Magli, M.; et al. Species-level differences in osmoprotectants and antioxidants contribute to stress tolerance of Quercus robur and Quercus cerris seedlings under water deficit and high temperatures. Plants 2022, 11, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabarijaona, A.; Ponton, S.; Bert, D.; Ducousso, A.; Richard, B.; Levillain, J.; Brendel, O. Provenance differences in water-use efficiency among sessile oak populations grown in a mesic common garden. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 914199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintó-Marijuan, M.; Joffre, R.; Casals, I.; De Agazio, M.; Zacchini, M.; García-Plazaola, J.I.; Esteban, R.; Aranda, X.; Guàrdia, M.; Fleck, I. Antioxidant and photoprotective responses to elevated CO2 and heat stress during holm oak regeneration by resprouting, evaluated with NIRS. Plant Biol. 2013, 15, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, P. Evaluation of antioxidant activity in oak leaves from the Republic of Moldova exposed to heat stress. J. Plant Dev. 2024, 31, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renninger, H.J.; Carlo, N.J.; Clark, K.L.; Schäfer, K.V.R. Resource use and efficiency and stomatal responses to environmental drivers of oak and pine species in an Atlantic Coastal Plain forest. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, R.J.; Bodénès, C.; Ducousso, A.; Roussel, G.; Kremer, A. Hybridization as a mechanism of invasion in oaks. New Phytol. 2004, 161, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussotti, F.; Pollastrini, M.; Holland, V.; Brüggemann, W. Functional traits and adaptive capacity of European forests to climate change. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2015, 111, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjevac, B. Regeneration of Sessile Oak Forests with the Undergrowth of Accompanying Tree Species in Northeastern Serbia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Belgrade–Faculty of Forestry, Belgrade, Serbia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Anić, I. History of Pedunculate Oak Forest Regeneration in Croatia. Šumarski List 2025, 149, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, G.W.; Canham, C.D.; Lertzman, K.P. Gap Light Analyzer (GLA), Version 2.0: Imaging Software to Extract Canopy Structure and Gap Light Transmission Indices from True-Colour Fisheye Photographs; Simon Fraser University: Burnaby, BC, Canada; Institute of Ecosystem Studies: Millbrook, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Gross, J.; Ligges, U. Nortest: Tests for Normality, R package version 1.0-4; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2015. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nortest (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.john-fox.ca/Companion (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Hothorn, T.; Bretz, F.; Westfall, P. Simultaneous Inference in General Parametric Models. Biom. J. 2008, 50, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Christensen, R.H.B. lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 82, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, T. Patchwork: The Composer of Plots, R package version 1.2.0; Thomas Lin Pedersen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation, R package version 1.1.4; Posit Software, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=dplyr (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Grolemund, G.; Wickham, H. Dates and Times Made Easy with lubridate. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 40, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonito, A.; Varone, L.; Gratani, L. Relationship between acorn size and seedling morphological and physiological traits of Quercus ilex L. from different climates. Photosynthetica 2011, 49, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siam, A.M.J.; Radoglou, K.M.; Noitsakis, B.; Smiris, P. Physiological and growth responses of three Mediterranean oak species to different water availability regimes. J. Arid Environ. 2008, 72, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peguero-Pina, J.J.; Sancho-Knapik, D.; Morales, F.; Flexas, J.; Gil-Pelegrín, E. Differential photosynthetic performance and photoprotection mechanisms of three Mediterranean evergreen oaks under severe drought stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 2009, 36, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojnić, S.; Pekeč, S.; Kebert, M.; Pilipović, A.; Stojanović, D.; Stojanović, M.; Orlović, S. Drought Effects on Physiology and Biochemistry of Pedunculate Oak (Quercus robur L.) and Hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.) Saplings Grown in Urban Area of Novi Sad, Serbia. S.-East Eur. For. 2016, 7, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Kang, J.W.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, W.Y. Growth and Physiological Responses of Quercus acutissima Seedling Under Drought Stress. Plant Breed. Biotech. 2017, 5, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granier, A.; Bréda, N. Modelling canopy conductance and stand transpiration of an oak forest from sap flow measurements. Ann. For. Sci. 1996, 53, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes, F.; Vitale, M.; Donato, E.; Giannini, M.; Puppi, G. Different ability of three Mediterranean oak species to tolerate progressive water stress. Photosynthetica 2006, 44, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftoyannis, Y.; Radoglou, K.; Halivopoulos, G. Ecophysiology and Survival of Acer pseudoplatanus L., Castanea sativa Miller. and Quercus frainetto Ten. Seedlings on a Reforestation Site in Northern Greece. New For. 2006, 31, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, L. Effects of Drought Stress and Rehydration on Physiological and Biochemical Properties of Four Oak Species in China. Plants 2022, 11, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limousin, J.; Roussel, A.; Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Torres-Ruiz, J.M.; Moreno, M.; Garcia De Jalon, L.; Ourcival, J.; Simioni, G.; Cochard, H.; Martin-StPaul, N. Drought acclimation of Quercus ilex leaves improves tolerance to moderate drought but not resistance to severe water stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 1967–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahall, B.E.; Tyler, C.M.; Cole, E.S.; Mata, C. A comparative study of oak (Quercus, Fagaceae) seedling physiology during summer drought in southern California. Am. J. Bot. 2009, 96, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, Q.S. Comparing the Physiological Drought Responses of Red Oak (Quercus rubra) and Red Maple (Acer rubrum). Master’s Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vitale, M.; Anselmi, S.; Salvatori, E.; Manes, F. New approaches to study the relationship between stomatal conductance and environmental factors under Mediterranean climatic conditions. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 5385–5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blujdea, V.; Paucă, M.C.; Ionescu, M. Mechanisms of drought tolerance in mesoxerophytic oaks. Analele ICAS 2003, 46, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bréda, N.; Huc, R.; Granier, A.; Dreyer, E. Temperate forest trees and stands under severe drought: A review of ecophysiological responses, adaptation processes and long-term consequences. Ann. For. Sci. 2006, 63, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcsán, A.; Steppe, K.; Sárközi, E.; Erdélyi, É.; Missoorten, M.; Mees, G.; Mijnsbrugge, K.V. Early Summer Drought Stress During the First Growing Year Stimulates Extra Shoot Growth in Oak Seedlings (Quercus petraea). Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, M.A.; Donahue, R.A.; Poulson, M.E. Physiological Response of Garry Oak (Quercus garryana) Seedlings to Drought. Northwest Sci. 2017, 91, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urli, M.; Lamy, J.B.; Sin, F.; Burlett, R.; Delzon, S.; Porte, A.J. The high vulnerability of Quercus robur to drought at its southern margin paves the way for Quercus ilex. Plant Ecol. 2015, 216, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamjav, B. Adaptability responses to drought stress in the oak species Quercus petraea growing on dry sites. J. For. Sci. 2022, 68, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mészáros, I.; Láposi, R.; Veres, S.; Bai, E.; Lakatos, G.; Gáspár, A.; Mile, O. Effects of Supplemental UV-B and Drought Stress on Photosynthetic Activity of Sessile Oak (Quercus petraea L.). In Proceedings of the 12th International Congress on Photosynthesis, Sydney, Australia, 18–23 August 2001; CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia; pp. S3–036. [Google Scholar]

- Epron, D.; Dreyer, E.; Aussenac, G. A comparison of photosynthetic responses to water stress in seedlings from 3 oak species: Quercus petraea (Matt) Liebl, Q rubra L. and Q cerris L. Ann. For. Sci. 1993, 50, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolev, K.; Anev, S. Physiological aspects of natural regeneration in coppiced forest dominated by Quercus frainetto Ten. and Quercus cerris L. For. Ideas 2022, 28, 446–454. [Google Scholar]

- Hashoum, H.; Gavinet, J.; Gauquelin, T.; Baldy, V.; Dupouyet, S.; Fernandez, C.; Bousquet-Mélou, A. Chemical interaction between Quercus pubescens and its companion species is not emphasized under drought stress. Eur. J. For. Res. 2021, 140, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardini, A.; Pitt, F. Drought resistance of Quercus pubescens as a function of root hydraulic conductance, xylem embolism and hydraulic architecture. New Phytol. 1999, 143, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilnitsky, O.A.; Plugatar, Y.V.; Pashtetsky, A.V.; Gil, A.T. Features of Photosynthesis and Water Regime of Quercus Pubescens Willd. Under The Conditions of Autumn Drought of The Southern Coast of The Crimea. BIO Web Conf. 2021, 39, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batziou, M.; Milios, E.; Kitikidou, K. Is diameter at the base of the root collar a key characteristic of seedling sprouts in a Quercus pubescens—Quercus frainetto grazed forest in north-eastern Greece? A morphological analysis. New For. 2017, 48, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hees, A.F.M. Growth and morphology of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L) and beech (Fagus sylvatica L) seedlings in relation to shading and drought. Ann. For. Sci. 1997, 54, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Díez, P.; Navarro, J.; Pintado, A.; Sancho, L.G.; Maestro, M. Interactive effects of shade and irrigation on the performance of seedlings of three Mediterranean Quercus species. Tree Physiol. 2006, 26, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farque, L.; Sinoquet, H.; Colin, F. Canopy structure and light interception in Quercus petraea seedlings in relation to light regime and plant density. Tree Physiol. 2001, 21, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunzweig, J.M.; Carmel, Y.; Riov, J.; Sever, N.; McCreary, D.D.; Flather, C.H. Growth, resource storage, and adaptation to drought in California and eastern Mediterranean oak seedlings. Can. J. For. Res. 2008, 38, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löf, M.; Welander, N.T. Influence of herbaceous competitors on early growth in direct seeded Fagus sylvatica L. and Quercus robur L. Ann. For. Sci. 2004, 61, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, K.H.; Wood, V. Drought susceptibility and xylem dysfunction in seedlings of 4 European oak species. Ann. For. Sci. 1995, 52, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Ai, W.; Zhan, H.; Ma, S.; Lu, X. Non-Structural Carbohydrates and Growth Adaptation Strategies of Quercus mongolica Fisch. ex Ledeb. Seedlings under Drought Stress. Forests 2023, 14, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.E.; Tomlinson, P.T. Oak growth, development and carbon metabolism in response to water stress. Ann. For. Sci. 1996, 53, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.C.; Jacobs, D.; McNabb, K.; Miller, G.; Baldwin, V.; Foster, G. Artificial Regeneration of Major Oak (Quercus) Species in the Eastern United States—A Review of the Literature. For. Sci. 2008, 54, 77–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossnickle, S.C.; Ivetić, V. Direct Seeding in Reforestation—A Field Performance Review. Reforesta 2017, 4, 94–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löf, M.; Birkedal, M. Direct seeding of Quercus robur L. for reforestation: The influence of mechanical site preparation and sowing date on early growth of seedlings. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, F.B.; Jiménez, M.N.; Ripoll, M.Á.; Fernández-Ondoño, E.; Gallego, E.; De Simón, E. Direct sowing of holm oak acorns: Effects of acorn size and soil treatment. Ann. For. Sci. 2006, 63, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | Coordinates | Plant Community | Altitude (m) | Parent Material | Soil Type | Organic Layer (cm) | Canopy Closure (%) | Overstory Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cer | 44.64881453° N, 19.42372202° E | Quercetum frainetto-cerridis Rudski (1940) 1949 | 217 | Sandstones, argillophyllites and phyllites | Luvisol | 5 | 70 | Quercus frainetto, Tilia cordata, Carpinus betulus |

| Debeli Lug | 44.32694° N, 21.88722° E | Festuco drymeiae-Quercetum petraeae Janković 1968 | 537 | Schists | Cambisol | 4/5 | 70 | Quercus petraea, Carpinus betulus, Fraxinus excelsior, Fagus sylvatica |

| Vraćevšnica | 44.06519794° N, 20.60490133° E | Quercetum frainetto-cerridis Rudski (1940) 1949 | 430 | Sandstones | Cambisol | 7 | 70 | Quercus frainetto, Quercus cerris, Fagus sylvatica |

| Žiča | 43.6925° N, 20.64333° E | Quercetum frainetto-cerridis Rudski (1940) 1949 | 241 | Clay | Planosol | 4 | 80 | Quercus frainetto, Quercus cerris, Carpinus betulus |

| Morphological Parameter | Source of Variation | df | F-Value | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height (cm) | Species | 3 | 10.38 | 1.14 × 10−6 | *** |

| Location | 3 | 21.80 | 1.95 × 10−13 | *** | |

| Species × Location | 9 | 1.88 | 0.052 | ns | |

| Diameter (mm) | Species | 3 | 37.47 | 2.90 × 10−22 | *** |

| Location | 3 | 47.53 | 1.16 × 10−27 | *** | |

| Species × Location | 9 | 5.96 | 5.00 × 10−8 | *** |

| Physiological Parameter | Term | AM | PM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | t-Value | p-Value | df | t-Value | p-Value | ||

| PhiPSII | (Intercept) | 3499.9 | 17.78 | 9.5 × 10−68 *** | 2959.3 | 15.61 | 7.99 × 10−53 *** |

| Q. frainetto | 632.2 | −0.59 | 0.554 | 569.2 | 0.99 | 0.324 | |

| Q. petraea | 654.4 | −2.01 | 0.045 * | 592.0 | 0.12 | 0.903 | |

| Q. pubescens | 634.3 | 1.13 | 0.258 | 570.9 | 1.11 | 0.268 | |

| Debeli Lug | 750.1 | 1.87 | 0.062 | 706.7 | 2.26 | 0.024 * | |

| Vraćevšnica | 643.8 | −6.93 | 1.0 × 10−11 *** | 554.5 | 0.03 | 0.974 | |

| Žiča | 600.5 | 2.42 | 0.016 * | 558.8 | 4.19 | 3.18 × 10−5 *** | |

| Soil moisture content | 3099.4 | −2.29 | 0.022 * | 2508.4 | −5.31 | 1.21 × 10−7 *** | |

| Soil temperature | 3030.8 | −7.30 | 3.5 × 10−13 *** | 2479.8 | 1.68 | 0.094 | |

| Air temperature | 3015.6 | 9.01 | 3.7 × 10−19 *** | 2491.2 | −1.49 | 0.137 | |

| Air humidity | 3013.2 | 8.22 | 3.1 × 10−16 *** | 2463.1 | 5.02 | 5.67 × 10−7 *** | |

| Q. frainetto × Debeli Lug | 585.0 | 0.34 | 0.732 | 536.3 | −0.23 | 0.815 | |

| Q. petraea × Debeli Lug | 603.0 | 2.16 | 0.031 * | 554.3 | −1.02 | 0.308 | |

| Q. pubescens × Debeli Lug | 579.3 | −0.61 | 0.544 | 532.5 | −0.53 | 0.600 | |

| Q. frainetto × Vraćevšnica | 582.0 | 1.36 | 0.173 | 534.3 | −0.74 | 0.461 | |

| Q. petraea × Vraćevšnica | 600.3 | 1.05 | 0.295 | 552.0 | −0.93 | 0.353 | |

| Q. pubescens × Vraćevšnica | 575.0 | −1.54 | 0.125 | 529.5 | −0.80 | 0.424 | |

| Q. frainetto × Žiča | 564.3 | 0.74 | 0.457 | 522.0 | −0.62 | 0.539 | |

| Q. petraea × Žiča | 548.6 | 1.83 | 0.067 | 513.0 | −0.01 | 0.989 | |

| Q. pubescens × Žiča | 523.9 | −0.21 | 0.834 | 493.0 | −0.72 | 0.469 | |

| gtw | (Intercept) | 3410.2 | 6.65 | 3.48 × 10−11 *** | 2945.2 | −1.94 | 0.052 |

| Q. frainetto | 574.9 | −1.30 | 0.193 | 611.7 | 0.72 | 0.469 | |

| Q. petraea | 593.8 | −1.29 | 0.197 | 636.6 | 0.88 | 0.381 | |

| Q. pubescens | 576.3 | 0.57 | 0.568 | 613.6 | 1.37 | 0.171 | |

| Debeli Lug | 649.1 | 2.73 | 0.006 ** | 769.6 | 4.50 | 7.71 × 10−6 *** | |

| Vraćevšnica | 582.2 | −0.32 | 0.752 | 594.7 | 5.52 | 5.09 × 10−8 *** | |

| Žiča | 555.6 | −4.03 | 6.5 × 10−5 *** | 599.6 | 0.03 | 0.974 | |

| Soil moisture content | 3061.3 | −6.03 | 1.87 × 10−9 *** | 2539.5 | 5.61 | 2.26 × 10−8 *** | |

| Soil temperature | 3012.7 | −0.30 | 0.762 | 2510.0 | −3.78 | 1.63 × 10−4 *** | |

| Air temperature | 3001.7 | −7.06 | 2.05 × 10−12 *** | 2521.5 | 3.70 | 2.21 × 10−4 *** | |

| Air humidity | 3000.4 | 10.92 | 2.91 × 10−27 *** | 2492.6 | 12.22 | 2.08 × 10−33 *** | |

| Q. frainetto × Debeli Lug | 545.3 | 1.75 | 0.081 | 573.8 | 0.05 | 0.960 | |

| Q. petraea × Debeli Lug | 560.1 | 0.58 | 0.564 | 593.5 | −1.23 | 0.221 | |

| Q. pubescens × Debeli Lug | 541.9 | −0.60 | 0.548 | 569.4 | −1.30 | 0.194 | |

| Q. frainetto × Vraćevšnica | 543.5 | 0.85 | 0.394 | 571.4 | −1.91 | 0.057 | |

| Q. petraea × Vraćevšnica | 558.3 | 0.38 | 0.703 | 590.9 | −2.50 | 0.013 * | |

| Q. pubescens × Vraćevšnica | 539.1 | −1.07 | 0.286 | 565.9 | −2.64 | 0.008 ** | |

| Q. frainetto × Žiča | 533.3 | 1.13 | 0.258 | 557.0 | −0.83 | 0.410 | |

| Q. petraea × Žiča | 524.3 | 0.89 | 0.373 | 546.5 | −0.90 | 0.368 | |

| Q. pubescens × Žiča | 506.8 | −0.51 | 0.610 | 523.9 | −1.55 | 0.123 | |

| Physio- Logical Parameter | Term | AM | PM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | t-Value | p-Value | df | t-Value | p-Value | ||

| PhiPSII | (Intercept) | 439.6 | 0.22 | 0.825 | 292.0 | 0.52 | 0.603 |

| Q. frainetto | 114.2 | 0.87 | 0.385 | 105.6 | 1.45 | 0.150 | |

| Q. petraea | 121.4 | 0.17 | 0.867 | 109.8 | 0.06 | 0.956 | |

| Q. pubescens | 101.6 | 0.42 | 0.679 | 88.9 | 1.27 | 0.206 | |

| Debeli Lug | 115.2 | 2.06 | 0.042 * | 105.8 | −0.55 | 0.585 | |

| Vraćevšnica | 102.7 | 0.20 | 0.840 | 94.6 | 0.88 | 0.383 | |

| Žiča | 119.6 | 4.21 | 4.940 × 10−5 *** | 100.7 | 2.70 | 0.008 ** | |

| Soil moisture content | 385.4 | −6.36 | 5.668 × 10−10 *** | 252.6 | −0.48 | 0.629 | |

| Soil temperature | 378.6 | −1.87 | 0.063 | 257.5 | −1.29 | 0.199 | |

| Air temperature | 370.6 | 3.47 | 6.0 × 10−4 *** | 251.6 | 3.80 | 2.0 × 10−4 *** | |

| Air humidity | 367.3 | 5.33 | 1.68 × 10−7 *** | 246.9 | −0.17 | 0.868 | |

| Q. frainetto × Debeli Lug | 87.1 | −1.00 | 0.321 | 79.0 | −0.65 | 0.517 | |

| Q. petraea × Debeli Lug | 99.3 | 0.44 | 0.661 | 89.4 | 0.78 | 0.436 | |

| Q. frainetto × Vraćevšnica | 74.7 | 0.03 | 0.973 | 70.1 | −0.58 | 0.566 | |

| Q. petraea × Vraćevšnica | 90.3 | 0.12 | 0.906 | 82.3 | −0.41 | 0.683 | |

| Q. pubescens × Vraćevšnica | 91.3 | −0.29 | 0.769 | 81.1 | −1.28 | 0.206 | |

| Q. frainetto × Žiča | 105.3 | −2.28 | 0.025 | 97.4 | −2.37 | 0.020 ** | |

| Q. petraea × Žiča | 102.5 | −0.80 | 0.428 | 92.9 | −0.71 | 0.481 | |

| Q. pubescens × Žiča | 94.9 | −1.27 | 0.207 | 84.5 | −1.76 | 0.082 | |

| gtw | (Intercept) | 435.2 | 5.35 | 1.40 × 10−7 *** | 311.7 | 3.21 | 0.001 ** |

| Q. frainetto | 154.4 | 0.80 | 0.426 | 171.4 | 1.21 | 0.228 | |

| Q. petraea | 165.2 | 1.20 | 0.230 | 172.5 | −0.37 | 0.709 | |

| Q. pubescens | 136.4 | 0.09 | 0.925 | 141.2 | −0.66 | 0.508 | |

| Debeli Lug | 156.7 | 2.80 | 0.006 ** | 172.8 | 1.88 | 0.062 | |

| Vraćevšnica | 136.3 | 1.68 | 0.096 | 149.2 | −0.82 | 0.414 | |

| Žiča | 163.6 | 0.46 | 0.645 | 164.4 | −0.93 | 0.352 | |

| Soil moisture content | 411.4 | −1.56 | 0.119 | 292.9 | −2.06 | 0.040 * | |

| Soil temperature | 405.2 | −2.31 | 0.022 * | 303.0 | −3.74 | 2.19 × 10−4 *** | |

| Air temperature | 395.8 | −1.56 | 0.120 | 292.6 | 0.18 | 0.859 | |

| Air humidity | 392.7 | −1.84 | 0.066 | 290.4 | 3.26 | 0.001 ** | |

| Q. frainetto × Debeli Lug | 111.2 | −1.89 | 0.061 | 113.6 | −1.18 | 0.239 | |

| Q. petraea × Debeli Lug | 129.9 | −1.39 | 0.167 | 133.0 | 0.44 | 0.660 | |

| Q. frainetto × Vraćevšnica | 90.2 | 0.65 | 0.515 | 91.2 | −1.01 | 0.317 | |

| Q. petraea × Vraćevšnica | 115.5 | −0.02 | 0.987 | 117.5 | −1.02 | 0.312 | |

| Q. pubescens × Vraćevšnica | 117.9 | 0.29 | 0.774 | 119.1 | −0.49 | 0.622 | |

| Q. frainetto × Žiča | 139.8 | −0.95 | 0.345 | 151.9 | −0.89 | 0.373 | |

| Q. petraea × Žiča | 133.3 | −1.24 | 0.217 | 135.4 | −0.35 | 0.728 | |

| Q. pubescens × Žiča | 123.0 | −0.24 | 0.814 | 124.2 | 0.60 | 0.548 | |

| Parameter | Coefficient | SE | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% CI (OR) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −9.858 | 1.316 | 0.000052 | 0.0000033–0.00059 | <0.001 *** |

| Mean PhiPSII (per 0.05 unit) | 0.7056 | 0.100 | 2.03 | 1.68–2.49 | <0.001 *** |

| Mean gtw (per mmol m−2 s−1) | 0.0981 | 0.021 | 1.1 | 1.06–1.15 | <0.001 *** |

| Species (ref. Q. cerris) | |||||

| Q. frainetto | 0.5464 | 0.438 | 1.73 | 0.74–4.18 | 0.212 |

| Q. petraea | −0.2927 | 0.404 | 0.75 | 0.34–1.65 | 0.469 |

| Q. pubescens | −0.4125 | 0.416 | 0.66 | 0.29–1.50 | 0.322 |

| Location (ref. Cer) | |||||

| Debeli Lug | 0.9734 | 0.465 | 2.65 | 1.08–6.77 | 0.036 * |

| Vraćevšnica | 1.9044 | 0.452 | 6.72 | 2.83–16.77 | <0.001 *** |

| Žiča | −0.7081 | 0.437 | 0.49 | 0.21–1.15 | 0.106 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mijatović, L.; Kanjevac, B.; Ljubičić, J.; Kerkez Janković, I.; Devetaković, J. Early Post-Germination Physiological Traits of Oak Species Under Various Environmental Conditions in Oak Forests. Forests 2026, 17, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010003

Mijatović L, Kanjevac B, Ljubičić J, Kerkez Janković I, Devetaković J. Early Post-Germination Physiological Traits of Oak Species Under Various Environmental Conditions in Oak Forests. Forests. 2026; 17(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleMijatović, Ljubica, Branko Kanjevac, Janko Ljubičić, Ivona Kerkez Janković, and Jovana Devetaković. 2026. "Early Post-Germination Physiological Traits of Oak Species Under Various Environmental Conditions in Oak Forests" Forests 17, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010003

APA StyleMijatović, L., Kanjevac, B., Ljubičić, J., Kerkez Janković, I., & Devetaković, J. (2026). Early Post-Germination Physiological Traits of Oak Species Under Various Environmental Conditions in Oak Forests. Forests, 17(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010003