A Comparative Analysis of UAV LiDAR and Mobile Laser Scanning for Tree Height and DBH Estimation in a Structurally Complex, Mixed-Species Natural Forest

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

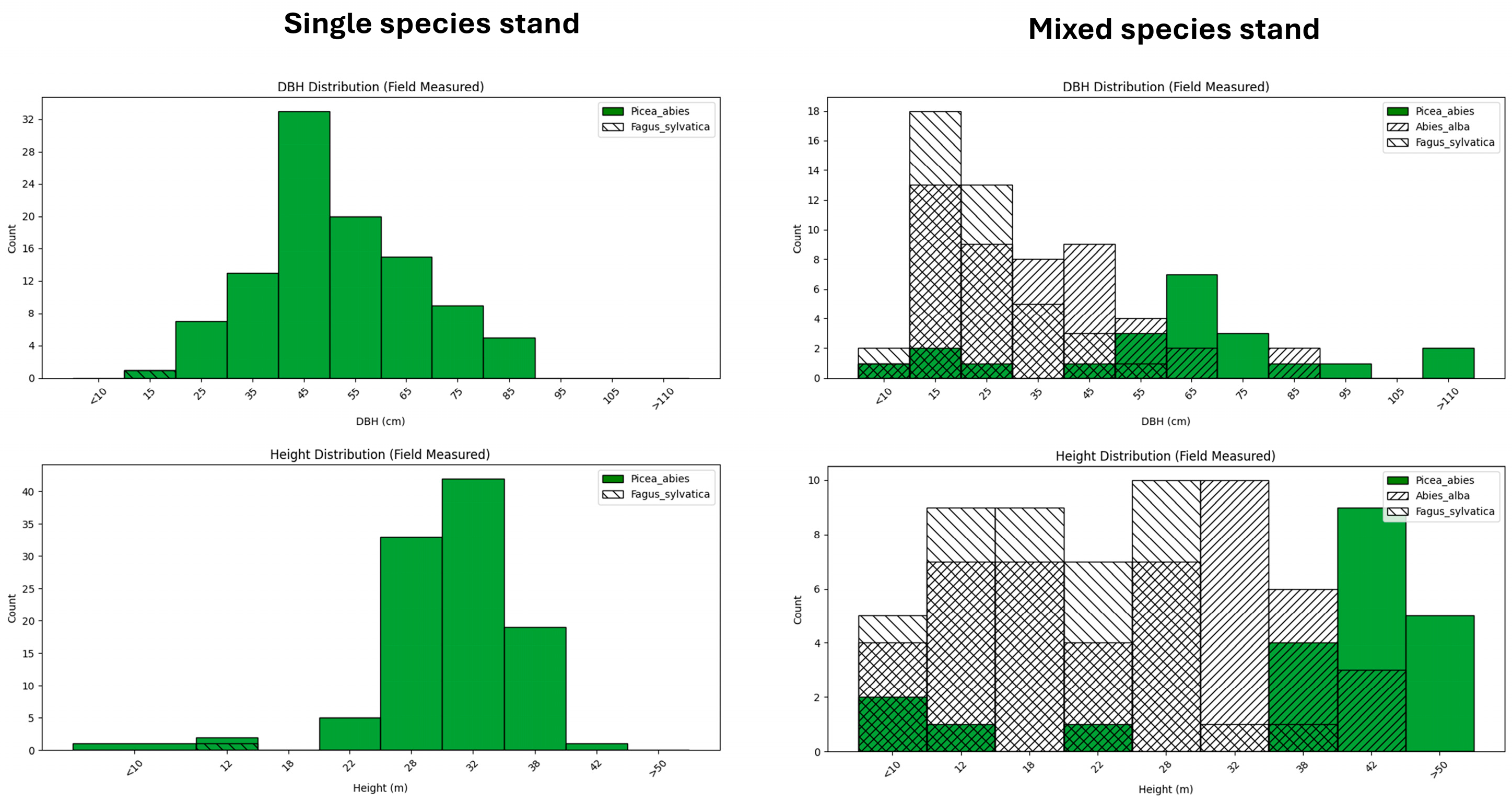

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Data Collection

2.3. UAV LiDAR Acquisition and Processing

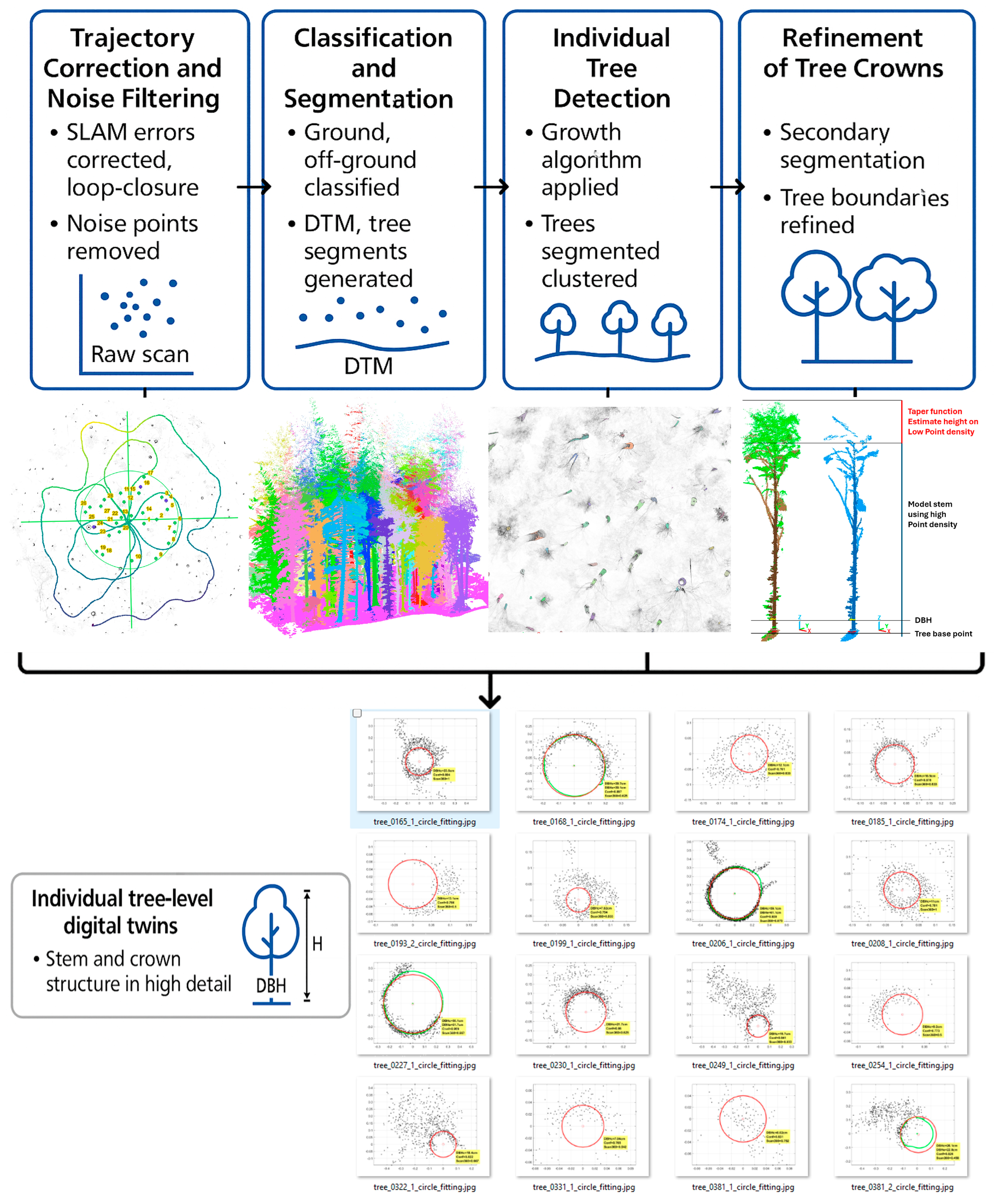

2.4. Mobile Laser Scanning (MLS) Acquisition and Processing

- Trajectory Correction and Noise Filtering: SLAM errors were corrected through loop-closure algorithms, and noise points were removed using statistical outlier filtering.

- Classification and Segmentation: Points were classified into ground and off-ground returns. Ground points were used to construct a Digital Terrain Model (DTM), while off-ground points were used for tree segmentation.

- Individual Tree Detection: Off-ground points were segmented into individual trees using an accretion-based growth algorithm. Starting from seed points representing local apexes, points were progressively clustered based on vertical connectivity and spatial coherence. The algorithm takes three steps to estimate each tree’s footprint simultaneously. It begins at a large nucleus of points with high density and then grows by accretion until it meets neighboring trees.

- Refinement of Tree Crowns: In dense stands or regeneration patches where trees overlapped or were double-stemmed, a secondary segmentation step was applied. This used local neighborhood rules (crown diameter, minimum tree distance) and manual correction to refine tree boundaries and reduce merging errors.

2.5. Occlusion Mapping

2.6. Data Integration and Accuracy Assessment

3. Results

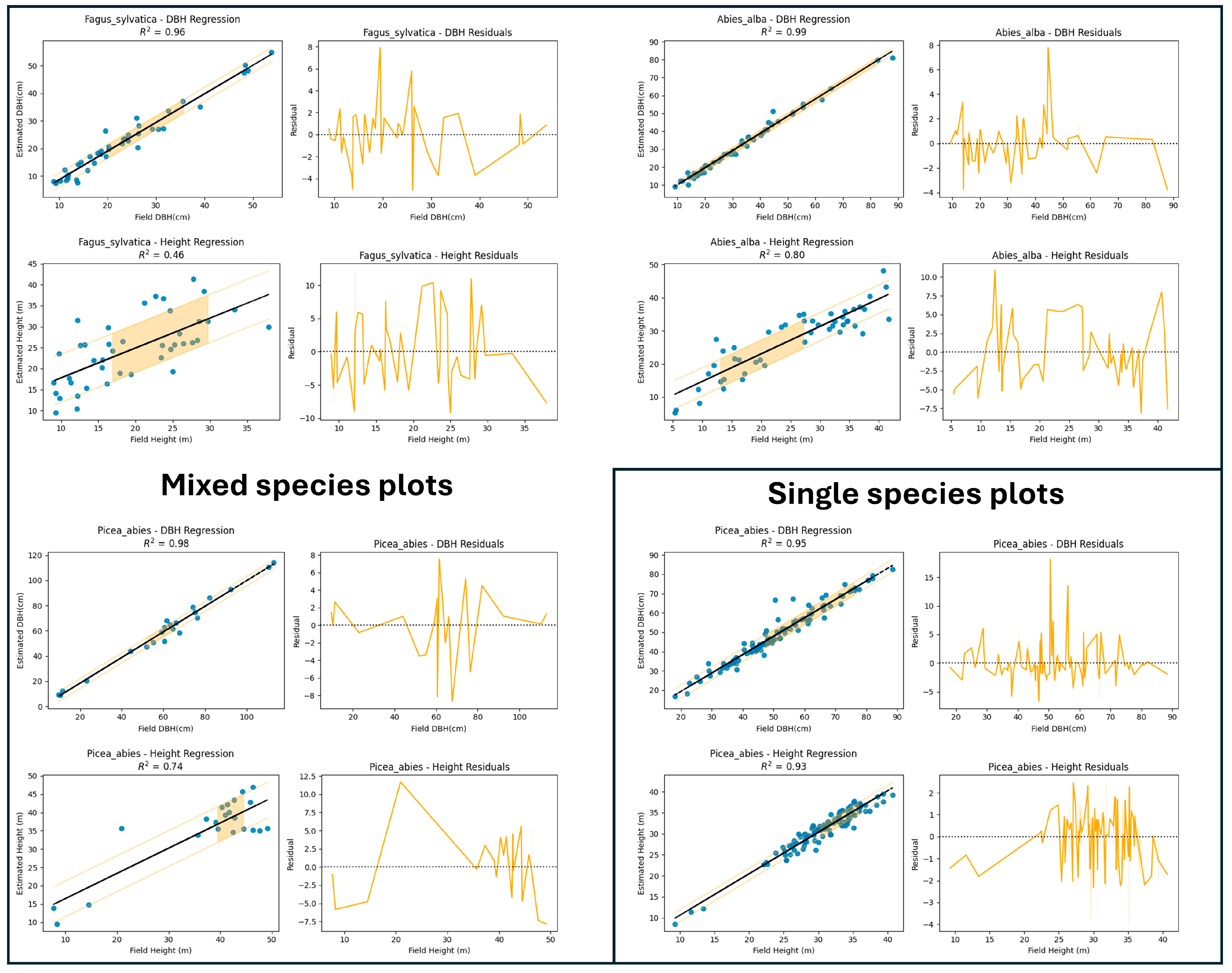

3.1. Accuracy of MLS in Estimating Tree Height and DBH

3.2. Influence of Plot Structure on Estimation Accuracy

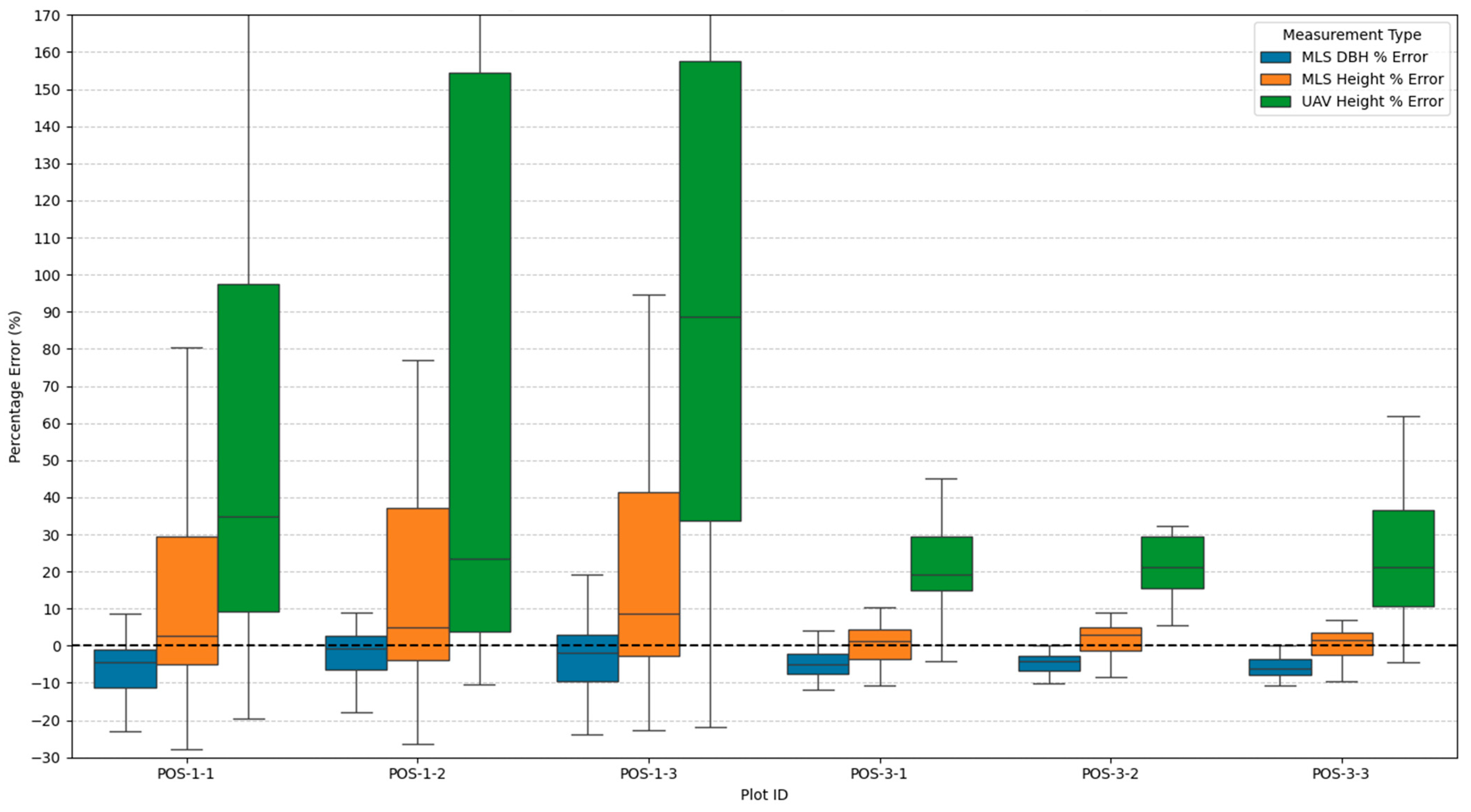

3.3. Accuracy of UAV-Derived Tree Heights

3.4. Visual Analysis and Point Density Considerations

3.5. Analysis of Occlusion and Canopy Layering Limitations

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of UAV and MLS Performance in Height and DBH Estimation

4.2. Influence of Tree Species and Forest Structure

4.3. Sources of Uncertainty and Limitations

4.4. Practical Implications and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niță, M.D. Testing Forestry Digital Twinning Workflow Based on Mobile LiDAR Scanner and AI Platform. Forests 2021, 12, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutcă, I.; Cernat, A.; Stăncioiu, P.T.; Ioraș, F.; Niță, M.D. Does Slope Aspect Affect the Aboveground Tree Shape and Volume Allometry of European Beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) Trees? Forests 2022, 13, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; Defries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chapin, F.S.; Coe, M.T.; Daily, G.C.; Gibbs, H.K.; et al. Global Consequences of Land Use. Science 2005, 309, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianidis, E.; Akca, D.; Poli, D.; Hofer, M.; Gruen, A.; Sanchez Martin, V.; Smagas, K.; Walli, A.; Altan, O.; Jimeno, E.; et al. FORSAT: A 3D Forest Monitoring System for Cover Mapping and Volumetric 3D Change Detection. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2020, 13, 854–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Sun, Y.; Jia, W.; Li, D.; Zou, M.; Zhang, M. Study on the Estimation of Forest Volume Based on Multi-Source Data. Sensors 2021, 21, 7796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, S.C.; Wynne, R.H.; Nelson, R.F. Measuring Individual Tree Crown Diameter with Lidar and Assessing Its Influence on Estimating Forest Volume and Biomass. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 29, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baban, G.; Daniel Niţă, M. Measuring Forest Height from Space. Opportunities and Limitations Observed in Natural Forests. Measurement 2023, 211, 112593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, P.; Li, X.; Hernandez-Serna, A.; Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M.C.; Kommareddy, A.; Pickens, A.; Turubanova, S.; Tang, H.; Silva, C.E.; et al. Mapping Global Forest Canopy Height through Integration of GEDI and Landsat Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 253, 112165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holopainen, M.; Vastaranta, M.; Kankare, V.; Räty, M.; Vaaja, M.; Liang, X.; Yu, X.; Hyyppä, J.; Hyyppä, H.; Viitala, R.; et al. Biomass Estimation of Individual Trees Using Stem and Crown Diameter TLS Measurements. ISPRS—Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2012, XXXVIII-5/W12, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubayah, R.; Blair, J.B.; Goetz, S.; Fatoyinbo, L.; Hansen, M.; Healey, S.; Hofton, M.; Hurtt, G.; Kellner, J.; Luthcke, S.; et al. The Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation: High-Resolution Laser Ranging of the Earth’s Forests and Topography. Sci. Remote Sens. 2020, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassot, M.; Constant, T.; Fournier, M. The Use of Terrestrial LiDAR Technology in Forest Science: Application Fields, Benefits and Challenges. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, S.C.; Dutca, I.; Nita, M.D. Tradeoffs and Limitations in Determining Tree Characteristics Using 3D Pointclouds from Terrestrial Laser Scanning: A Comparison of Reconstruction Algorithms on European Bech (Fagus sylvatica L.) Trees. Ann. For. Res. 2024, 67, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, J.J.; Pedersen, P.B.M.; Moeslund, J.E.; Senf, C.; Treier, U.A.; Corcoran, D.; Koma, Z.; Nord-Larsen, T.; Normand, S. Temperate Forests of High Conservation Value Are Successfully Identified by Satellite and LiDAR Data Fusion. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2025, 7, e13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascu, I.S.; Dobre, A.C.; Badea, O.; Tănase, M.A. Estimating Forest Stand Structure Attributes from Terrestrial Laser Scans. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 691, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostol, B.; Chivulescu, S.; Ciceu, A.; Petrila, M.; Pascu, I.S.; Apostol, E.N.; Leca, S.; Lorent, A.; Tanase, M.; Badea, O. Data Collection Methods for Forest Inventory: A Comparison between an Integrated Conventional Equipment and Terrestrial Laser Scanning. Ann. For. Res. 2018, 61, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, P.; Jones, S.; Suarez, L.; Mellor, A.; Woodgate, W.; Soto-Berelov, M.; Haywood, A.; Skidmore, A. Mapping Forest Canopy Height Across Large Areas by Upscaling ALS Estimates with Freely Available Satellite Data. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 12563–12587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhao, A.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, H. Comparison of Modeling Algorithms for Forest Canopy Structures Based on UAV-LiDAR: A Case Study in Tropical China. Forests 2020, 11, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windrim, L.; Bryson, M.; McLean, M.; Randle, J.; Stone, C. Automated Mapping of Woody Debris over Harvested Forest Plantations Using UAVs, High-Resolution Imagery, and Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöps, T.; Sattler, T.; Häne, C.; Pollefeys, M. 3D Modeling on the Go: Interactive 3D Reconstruction of Large-Scale Scenes on Mobile Devices. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on 3D Vision, Lyon, France, 19–22 October 2015; pp. 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Pearse, G.D.; Dash, J.P.; Persson, H.J.; Watt, M.S. Comparison of High-Density LiDAR and Satellite Photogrammetry for Forest Inventory. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 142, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.C.; Wulder, M.A.; Vastaranta, M.; Coops, N.C.; Pitt, D.; Woods, M. The Utility of Image-Based Point Clouds for Forest Inventory: A Comparison with Airborne Laser Scanning. Forests 2013, 4, 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroti, G.; Martínez-Espejo Zaragoza, I.; Piemonte, A. Accuracy Assessment in Structure from Motion 3D Reconstruction from UAV-Born Images: The Influence of the Data Processing Methods. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci.—ISPRS Arch. 2015, 40, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, A.; Gobakken, T.; Puliti, S.; Hauglin, M.; Naesset, E. Value of Airborne Laser Scanning and Digital Aerial Photogrammetry Data in Forest Decision Making. Silva Fenn. 2018, 52, 9923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglhaut, J.; Cabo, C.; Puliti, S.; Piermattei, L.; O’Connor, J.; Rosette, J. Structure from Motion Photogrammetry in Forestry: A Review. Curr. For. Rep. 2019, 5, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRue, E.A.; Fahey, R.; Fuson, T.L.; Foster, J.R.; Matthes, J.H.; Krause, K.; Hardiman, B.S. Evaluating the Sensitivity of Forest Structural Diversity Characterization to LiDAR Point Density. Ecosphere 2022, 13, e4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Hyyppä, J.; Kaartinen, H.; Lehtomäki, M.; Pyörälä, J.; Pfeifer, N.; Holopainen, M.; Brolly, G.; Francesco, P.; Hackenberg, J.; et al. International Benchmarking of Terrestrial Laser Scanning Approaches for Forest Inventories. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 144, 137–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochta, J.; Kruček, M.; Vrška, T.; Kraâl, K. 3D Forest: An Application for Descriptions of Three-Dimensional Forest Structures Using Terrestrial LiDAR. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puliti, S.; Dash, J.P.; Watt, M.S.; Breidenbach, J.; Pearse, G.D. A Comparison of UAV Laser Scanning, Photogrammetry and Airborne Laser Scanning for Precision Inventory of Small-Forest Properties. For. Int. J. For. Res. 2020, 93, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Shen, X.; Cao, L.; Wang, G.; Cao, F. Estimating Forest Structural Attributes Using UAV-LiDAR Data in Ginkgo Plantations. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 146, 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terryn, L.; Calders, K.; Bartholomeus, H.; Bartolo, R.E.; Brede, B.; D’hont, B.; Disney, M.; Herold, M.; Lau, A.; Shenkin, A.; et al. Quantifying Tropical Forest Structure through Terrestrial and UAV Laser Scanning Fusion in Australian Rainforests. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 271, 112912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, F.; Puletti, N.; Quatrini, V.; Travaglini, D.; Bottalico, F.; Corona, P.; Chirici, G. Integrating Terrestrial and Airborne Laser Scanning for the Assessment of Single-Tree Attributes in Mediterranean Forest Stands. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 51, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudose, N.C.; Ungurean, C.; Davidescu, Ș.; Clinciu, I.; Marin, M.; Nita, M.D.; Adorjani, A.; Davidescu, A. Torrential Flood Risk Assessment and Environmentally Friendly Solutions for Small Catchments Located in the Romania Natura 2000 Sites Ciucas, Postavaru and Piatra Mare. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INCDS “Marin Dracea” National Forest Inventory: Forest Resources Assessment in Romania, Cycle II. Available online: https://roifn.ro/site/rezultate-ifn-2/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Pretzsch, H.; Biber, P.; Schütze, G.; Uhl, E.; Rötzer, T. Forest Stand Growth Dynamics in Central Europe Have Accelerated since 1870. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calders, K.; Adams, J.; Armston, J.; Bartholomeus, H.; Bauwens, S.; Bentley, L.P.; Chave, J.; Danson, F.M.; Demol, M.; Disney, M.; et al. Terrestrial Laser Scanning in Forest Ecology: Expanding the Horizon. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 251, 112102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuville, R.; Bates, J.S.; Jonard, F. Estimating Forest Structure from UAV-Mounted LiDAR Point Cloud Using Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch, J.; Keren, S.; Govedar, Z. The Dinaric Mountains versus the Western Carpathians: Is Structural Heterogeneity Similar in Close-to-Primeval Abies–Picea–Fagus Forests? Eur. J. For. Res. 2021, 140, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.; Mason, E.; Xu, C.; Morgenroth, J. Estimating Individual Tree DBH and Biomass of Durable Eucalyptus Using UAV LiDAR. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 89, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, B.M.; Goyanes, G.; Pina, P.; Vassilev, O.; Heleno, S. Assessment of the Influence of Survey Design and Processing Choices on the Accuracy of Tree Diameter at Breast Height (DBH) Measurements Using UAV-Based Photogrammetry. Drones 2021, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor Stăncioiu, P.; Dutcă, I.; Constantin Florea, S.; Paraschiv, M. Measuring Distances and Areas under Forest Canopy Conditions—A Comparison of Handheld Mobile Laser Scanner and Handheld Global Navigation Satellite System. Forests 2022, 13, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, R.; Yan, F.; Guan, T.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; et al. Advancing Forest Plot Surveys: A Comparative Study of Visual vs. LiDAR SLAM Technologies. Forests 2024, 15, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollob, C.; Ritter, T.; Nothdurft, A. Forest Inventory with Long Range and High-Speed Personal Laser Scanning (PLS) and Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) Technology. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Gao, Z.; Sun, B.; Qin, P.; Li, Y.; Yan, Z. An Integrated Method for Estimating Forest-Canopy Closure Based on UAV LiDAR Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Kankare, V.; Hyyppä, J.; Wang, Y.; Kukko, A.; Haggrén, H.; Yu, X.; Kaartinen, H.; Jaakkola, A.; Guan, F.; et al. Terrestrial Laser Scanning in Forest Inventories. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 115, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, H.-G.; Bienert, A.; Scheller, S.; Keane, E. Automatic Forest Inventory Parameter Determination from Terrestrial Laser Scanner Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2008, 29, 1579–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Milioto, A.; Palazzolo, E.; Giguère, P.; Behley, J.; Stachniss, C. SuMa++: Efficient LiDAR-Based Semantic SLAM. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Macau, China, 3–8 November 2021; pp. 4530–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, M.E.; Jensen, J.; Raber, G.; Tullis, J.; Davis, B.A.; Thompson, G.; Schuckman, K. An Evaluation of Lidar-Derived Elevation and Terrain Slope in Leaf-off Conditions. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2005, 71, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Quackenbush, L.; Zhang, L. Trends in Automatic Individual Tree Crown Detection and Delineation—Evolution of LiDAR Data. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, M.; Andersen, H.E.; Morton, D.C.; Cook, B.D. Quantifying Boreal Forest Structure and Composition Using UAV Structure from Motion. Forests 2018, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupinambá-Simões, F.; Pascual, A.; Guerra-Hernández, J.; Ordóñez, C.; de Conto, T.; Bravo, F. Assessing the Performance of a Handheld Laser Scanning System for Individual Tree Mapping—A Mixed Forests Showcase in Spain. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plot ID | Trees/ha | Basal Area m2/ha | Quadratic Mean Diameter (cm) | SD (cm) | Lorey Mean Height (m) | SD (m) | Tree Species Richness | Shannon Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POS-1-1 | 385 | 61.21 | 45.0 | 25.1 | 38.1 | 12.0 | 3 | 1.06 |

| POS-1-2 | 407 | 66.45 | 45.6 | 23.9 | 38.7 | 11.9 | 3 | 1.04 |

| POS-1-3 | 462 | 40.89 | 33.6 | 18.4 | 32.4 | 10.2 | 5 | 1.11 |

| Mixed species stand | 418 | 56.18 | 41.4 | 22.4 | 37.0 | 11.4 | 5 | 1.13 |

| POS-3-1 | 495 | 101.80 | 51.2 | 14.4 | 32.2 | 4.6 | 1 | 0.00 |

| POS-3-2 | 297 | 86.34 | 60.9 | 15.2 | 34.2 | 5.7 | 1 | 0.00 |

| POS-3-3 | 352 | 67.61 | 49.5 | 14.4 | 30.4 | 5.7 | 2 | 0.14 |

| Single species stands | 381 | 85.25 | 53.4 | 14.8 | 32.4 | 5.2 | 2 | 0.05 |

| Plot Type | Metric | R2 | RMSE (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed-species | Mean Height | −0.149 | 12.51 |

| Mixed-species | Median Height | −0.21 | 12.83 |

| Mixed-species | Max Height | −1.21 | 17.35 |

| Single-species | Mean Height | 0.619 | 3.4 |

| Single-species | Median Height | 0.629 | 3.36 |

| Single-species | Max Height | −1.219 | 8.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mîzgaciu, L.; Tudoran, G.M.; Ciocan, A.E.; Stăncioiu, P.T.; Niță, M.D. A Comparative Analysis of UAV LiDAR and Mobile Laser Scanning for Tree Height and DBH Estimation in a Structurally Complex, Mixed-Species Natural Forest. Forests 2025, 16, 1481. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16091481

Mîzgaciu L, Tudoran GM, Ciocan AE, Stăncioiu PT, Niță MD. A Comparative Analysis of UAV LiDAR and Mobile Laser Scanning for Tree Height and DBH Estimation in a Structurally Complex, Mixed-Species Natural Forest. Forests. 2025; 16(9):1481. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16091481

Chicago/Turabian StyleMîzgaciu, Lucian, Gheorghe Marian Tudoran, Andrei Eugen Ciocan, Petru Tudor Stăncioiu, and Mihai Daniel Niță. 2025. "A Comparative Analysis of UAV LiDAR and Mobile Laser Scanning for Tree Height and DBH Estimation in a Structurally Complex, Mixed-Species Natural Forest" Forests 16, no. 9: 1481. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16091481

APA StyleMîzgaciu, L., Tudoran, G. M., Ciocan, A. E., Stăncioiu, P. T., & Niță, M. D. (2025). A Comparative Analysis of UAV LiDAR and Mobile Laser Scanning for Tree Height and DBH Estimation in a Structurally Complex, Mixed-Species Natural Forest. Forests, 16(9), 1481. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16091481