Abstract

Although forest tenure devolution has been widely implemented, limited research has examined the carbon sequestration effects of property rights, particularly the interactions among rights within the tenure bundle. This research quantifies the structure of forest tenure at the village level over a 20-year period (2000–2019) and links it with village-year satellite observations of forest carbon sequestration. Using two-way fixed effects regression, interaction effect models, and mediation analysis, the research examines the carbon responses to devolved forest tenure, with particular attention to the interactions among tenure rights and the heterogeneity across forest types. Empirical results indicate that the logging right constitutes the core component of the tenure bundle that promotes carbon sequestration in mature forests and shrublands. When the logging right was completely absent, the impact of ownership on carbon sequestration became insignificant. Tenure rights bundles interact significantly in shaping carbon sequestration outcomes in mature forests. Specifically, longer tenure duration reinforces the effects of ownership and logging rights, whereas transferability tends to substitute for their returns. In terms of young plantations, only official certification of ownership would promote their carbon sequestration and there are no interaction impacts between rights. Further analyses combining farmer behavior find that the reduction in logging intensity, rather than frequency, is a significant channel for logging rights to promote carbon sequestration of mature stands. Ownership increases the frequency but the intensity of afforestation/reforestation, which in turn increases carbon sequestration of young plantations.

1. Introduction

About 30% of carbon emissions caused by human activities are absorbed by terrestrial ecosystems each year [1], with forests accounting for over 92% of that in recent decades [2]. Given the potential and cost-effectiveness of forest-based natural climate solutions, forests have experienced growing interest to meet carbon targets of Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement [3,4]. However, forest carbon sequestration depends not only on ecological factors [5] but also on socioeconomic status and institutional arrangements [6]. The role of forest tenure in this context has long been a focus of research.

Globally, studies have shown that unclear tenure arrangements of forests hinder the realization of the potential for forest carbon sequestration [7,8]. For instance, Chhatre and Agrawal find that greater autonomy for local communities is associated with higher forest carbon storage [9]. Similarly, Kansanga and Luginaah emphasize that devolving land rights from central authorities to local residents—and enabling community-based land governance—can contribute positively to forest carbon sequestration [10]. In China, the impact of tenure reform is particularly significant due to the country’s vast forest area and the successive waves of collective forest tenure reform (CFTR) implemented since the late 20th century [11]. The essence of CFTR lies in the devolution of forest tenure to individual households, aiming to stimulate private initiative and enhance incentives for sustainable forestry development and forest conservation [12]. During the process, rights bundles of forest tenure in rural China have undergone several rounds of changes towards completeness and exclusivity, since selected bundles of rights are progressively devolved with specific institutional design [13,14]. A typical case is the second round of CFTR initiated in 2003, which clarified farmers’ rights to contract, manage, and transfer forestland through institutional improvements and legal certification [15]. Besides the temporal changes along institutional adjustments [16], the composition of bundles of rights and the extent to which these are allocated and devolved also differed across regions with local execution variation [17].

Most empirical evaluations—either explicitly or implicitly—adopt a bundle-of-rights perspective to assess outcomes of the CFTR. For example, Qin et al. group households into four owner types based on the bundles of rights each household holds: private plot, planter owning the plantation, joint-household contract, and single-household contract [18]. A joint regression model is further applied to analyze the impact of rights on forestry investment behavior [18]. Likewise, Wang et al. examine the effects of ownership, mortgage, and transfer rights on household forestry investment, finding that mortgage and transfer rights have a stronger stimulating effect on investment compared to ownership [19]. Liu et al. instead find that households with ownership and logging rights invest more labor and capital in forestland [20]. The decomposition of forest tenure into bundles of rights enables more accurate impact evaluations of the CFTR across different periods and local contexts. Yet, as Smith critics, while the bundle-of-rights framework offers a “convenient simplification”, it may overlook the structure and interactions between individual rights within the bundle [21]. Since different combinations of rights can produce varying incentives and outcomes [13,22], a key question answered in our study is the interaction impacts of different rights in the bundle in shaping the outcome of the CFTR.

Besides, existing evaluations of the CFTR primarily focus on its effects on forest area [11,23,24], farmer behavior [12,18,19,20,25], and household income [26,27]. The impact of CFTR on forest carbon sequestration remains limited, with only two studies identified to date. Zheng et al. report that the CFTR improves forest carbon sequestration efficiency by optimizing land use and industry structure [28]. Hu et al. point out that the CFTR enhances capital productivity and then improves forest carbon capacity [27]. These studies offer valuable insights into the relationship between the CFTR and forest carbon sequestration. However, a key research gap remains: both studies treat the reform as a comprehensive policy shock, without disentangling the effects of individual rights within the tenure bundle or examining how interactions among these rights influence carbon sequestration. In addition, the use of province-level data tends to obscure the socio-economic heterogeneity at China’s most fundamental administrative unit—the village.

The research question guiding this study is as follows: to what extent do tenure rights affect forest carbon sequestration, and can combinations of rights generate synergistic effects? This should be the first study to measure the carbon sequestration effects of forest tenure at the most fundamental unit of policy implementation in China, using a 20-year (2000–2019) village-level socio-ecological panel dataset combining policy text analysis, household survey, and satellite observations. Specifically, forest carbon sequestration is measured at the landscape level, which weakens carbon leakage issues that may occur at the household level. Meanwhile, since forests at different life stages and of different types vary significantly in both carbon sequestration capacity and management requirements [29], forest types are identified using land-use remote sensing images and overlaid with satellite observations of carbon sequestration. This approach enables distinguishing carbon sequestration differences of mature forests, young forests, and bush forests at the village-year level. Importantly, under a thorough institutional review, four core rights within China’s CFTR are clarified, and the interaction impacts of the rights on carbon outcomes are explored. Additionally, recognizing that household behavior is an important channel through which forest tenure reform affects forest conditions [30,31], this research integrates landscape-level impact evaluation with the extensive focus of micro-level household research, quantifying the marginal effects of the rights bundle on forest carbon outcomes through its influence on household forestry decisions. The empirical results confirm the importance of accounting for rights interactions and distinguishing among forest types [31].

The remainder of this research is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the institutional background of the CFTR, which supports the selection and design of the specific rights covered in this research. Section 3 introduces the data sources, variable settings, and empirical design. Section 4 presents and analyzes the empirical results, while Section 5 offers conclusions and recommendations.

2. Institutional Background

Modern property rights theory emphasizes that clearly defined rights help reduce transaction costs, thereby improving resource allocation efficiency [32,33]; however, the specific bundles of property rights that function effectively vary across different contexts and situations [13,16,17,22]. Adopting the bundle-of-rights perspective, this section reviews the most essential and substantially adjusted bundles of rights throughout the forest tenure reform process in China.

Following the founding of the People’s Republic of China, forestland was designated for collective ownership after a short period of private forestland ownership. In the 1980s, China launched the first-round tenure reform for collective forestland, i.e., the “Three Fixes” (San Ding in Chinese) [16], which contracted management rights and timber ownership to rural households [34]. However, due to unclear boundaries and the lack of supplementary policies, this round of reform did not meet social expectations [35]. Since then, the CFTR entered a phase of experimentation and adjustment [36].

After the pilot started in 2003, the central government scaled up the second round of reform nationwide in 2008 [15,35], with boundary demarcation, land use rights and timber ownership clarification, and transfer right confirmation. Supplementary policies such as harvest quota reform have also been gradually carried out [23].

Generally, from the first to the second round of reform, the security of rural households’ forest tenure has been strengthened. Most typically, forest tenure is officially certified at a higher level of authorities. While the first-round reform issued certificates by local authorities, the second round attached an additional stamp of the State Forestry Administration. Besides, the new certificate has detailed information on tree species, geographical boundaries, and tenure duration [37]. Specifically, the duration of tenure has been extended from the former 30 to 50 years to 70 years to fit with the long operating cycle of forestry.

Another important adjustment relates to the transfer of collective forestland and forest ownership. Before the second-round reform, there were no institutional norms for transfer, and many markets were dominated by local business owners and rural talents with non-transparent processes. These limitations received much attention during the second round of CFTR. Starting from the second-round reform, both central and local governments formulated official guidance on the procedures for forestland transfer and promoted the establishment of forest tenure trading platforms [38].

Policy fluctuations during the “Three Fixes” period induced widespread logging without subsequent reforestation in collective forestland [15]. In response, the central government put forward the harvest quota system [34], which increased transaction costs and hindered forestland transfer [39]. During the second round of forest tenure reform, the harvest quota system was adjusted and improved. The second-round reform promoted quota application with the land certificate and further decentralized quotas to counties or even villages, which increased rural households’ access to logging rights [37].

Overall, the changes of CFTR are mainly in ownership, tenure duration, transfer right, and logging right (Table 1). Existing studies also focus on these rights and indicate that the reform motivates afforestation/reforestation and management investments of rural households [15,19,20,25,40], thereby enhancing forest carbon sequestration [13,22]. Therefore, this study constructs indicators for each of the four rights and further measures their interaction impacts on forest carbon sequestration at the village level.

Table 1.

The key institutional changes of the CFTR.

3. Model and Data

3.1. Empirical Model

The empirical estimations start with measuring the effect of each property right on forest carbon sequestration. The following two-way fixed effects model is adopted,

where is carbon sequestration of the ’s forest type ( = mature, young, and bush, respectively, with definitions in Table 1) of the village in year . is a vector of variables describing the rights bundle of forest tenure of the village in year . Coefficients capture the carbon sequestration effects of property rights. Village fixed effects () account for time-invariant, village-specific characteristics that may influence forest carbon sequestration, such as local cultural traditions. Year fixed effects () capture macro-level shocks that vary over time but are common across villages, including events such as the launch of Phase II of the Natural Forest Protection Project in 2011. Standard errors are clustered at the village level to account for potential dependence between periods. is a vector of village-level controls, and is the error term. Each type of property rights is first introduced separately into , followed by simultaneous inclusion of all four property rights to capture the possibility that the government may make trade-offs between different rights in the process of decentralization.

To further detect the interaction impacts of different rights on carbon sequestration, model (1) is extended by incorporating the interaction term of each two types of rights as follows:

where and are the ’s and ’s type of property rights ( and ), respectively, and the other variables are defined the same as model (1). The interaction term is created by multiplying two property rights variables together, representing the combined effect of two property rights on forest carbon sequestration, which is not simply the sum of their individual effects. Coefficient of the interaction term captures the effect of one property right that depends on the level of the other property right. A significant and positive indicates that the two types of property rights enhance each other in promoting forest carbon sequestration, whereas a significant but negative indicates a substitution relationship between the two.

The assessment of carbon sequestration results at the landscape level is further integrated with extensive research on forestry management practices, aiming to explain the carbon sequestration outcomes of tenure bundles through changes in forestry actions. To this end, model (1) is extended by incorporating additional indicators related to forestry management practices, which is

where denotes the forestry actions at the village level in year , and the others are defined the same as in model (1). For mature forest stands and shrublands, harvesting behavior plays a significant role, whereas planting behavior is more critical for young plantations.

3.2. Variables and Data

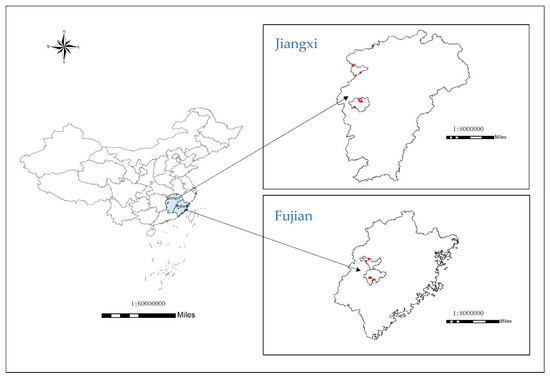

Since Fujian and Jiangxi led the pilot of the second-round reform, field visits were conducted in these two provinces during July–August of 2013, 2016, and 2019 to collect documents and carry out interviews aimed at assessing the impacts of forest tenure reform. Forest management and carbon sequestration have been sensitive to changes in forest tenure over the past two decades. Two counties were randomly selected from each province, followed by the random selection of three villages from each county and 15 rural households for each village, resulting in an initial sample of 12 villages and 180 rural households (Figure 1). Due to missing documents and the absence of respondents during revisits, the final empirical analyses included 193 village-level observations and 3243 household-level observations from 2000 to 2019, representing 80.4% and 90.1% of the originally sampled units, respectively.

Figure 1.

Research area (with boundaries in red).

Forest carbon sequestration is measured by the average annual net primary productivity (NPP) of forests at the village level. NPP is available at the MOD17A3HGF database of the Terra Net Primary Production on the NASA MODIS website (https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/search/, accessed on 12 July 2023) [41]. Land use classification imagery provided by the Data Center for Resources and Environmental Sciences of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (http://www.resdc.cn, accessed on 12 July 2023) categorizes forestland into mature forest stands with a canopy density greater than 30%, shrublands with a canopy density greater than 40%, and young forest stands with a canopy density of 30% or less. Maps of the NPP, land use classification, and village boundaries were overlaid using the Zonal Statistics tool in ArcGIS 10.7 to interpret village-level NPP across different forest types. Spatial resolution of the land use classification images is 30 m and the accuracy is 94.3% with field verification and error correction [42,43]. It should be noted that land use classification images are available from 2000 to 2015 among every 5 years. So annual NPP from 2000 to 2004 is extracted with land images of 2000, and the other periods are processed accordingly.

Data on property rights are derived from policy text analysis, supplemented by interviews with officers in county forestry bureaus and village leaders. Four indicators—ownership (own), tenure duration (dur), transfer rights (tran), and logging rights (log)—are used to characterize the core components of forest tenure in China, as outlined in Table 1. The first two are typically regarded as proxy indicators for security of forest tenure. An official certification reduces the risk of land redistribution and potential conflicts among stakeholders, and a longer contract period ensures that planters recoup their investments over the long growth period of forests. The variable own takes a value of 1 if rural households in the village hold an official certification assigned by both the central and local governments; otherwise, it is equal to 0. Given that the duration of tenure observed in the field survey ranged from less than 10 years to over 70 years, a five-point scale with an arithmetic sequence ranging from 0 to 1 was adopted, where higher values represent longer tenure durations (see Table 2). The variable tran takes a value of 1 when rural households can transfer forestland without any official and/or unofficial limitations and 0 otherwise. Rural households are required to apply for a harvesting quota for logging, while the application process is complicated, especially before the second round of the CFTR. Field survey finds that county administrations allocate quotas to different levels, i.e., towns, villages, or directly to households. Values of 0.2, 0.6, and 1 are assigned to the variable log when logging quotas are allocated to towns, villages, and households, respectively, with higher values indicating lower application costs.

Table 2.

Description of variables.

Besides topography of forestland, socioeconomic and climatic characteristics significantly affect rural households’ forestry decisions [40]. Village-level statistical documents are consulted, and the panel data are matched with two sets of socioeconomic variables. One relates to human capital endowments, including the average age, education, and health status of the village labor force. Another is the livelihood preference and economic development of the village represented by the percentage of off-farm employment and per capita income. In addition, the impact of climate on forest carbon sequestration is controlled by precipitation and temperature. The original dataset is available at the National Tibetan Plateau, which provides monthly precipitation and temperature at a spatial resolution of 1 km. The dataset is overlaid with the village boundaries map to calculate the average grid-level annual precipitation (by summing the monthly values) and temperature (by averaging the monthly values).

Due to the lack of detailed forestry data in village-level statistical documents, indicators for harvesting and planting are constructed based on face-to-face interviews with rural households. It should be noted that the face-to-face interviews conducted during the three waves of field surveys required respondents to retrospectively report forestry activities dating back to the year 2000. Although forestry management practices occur less frequently than crop cultivation, the extended recall period may still introduce recall bias. Nevertheless, this bias is unlikely to affect the estimation of Equation (3), as China’s forest tenure reform is a top-down policy initiative, with detailed regulations formulated at the provincial level. Consequently, the independent variables are only weakly correlated with household-level characteristics.

The definitions of the variables, along with their descriptive statistics, are presented in Table 2.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Tenure Rights and Carbon Sequestration

Table 3 reports the effects of tenure rights on forest carbon sequestration. Columns (1) to (4) present the regression results of each right separately. The results show that the logging right has a significantly positive effect on forest carbon sequestration, with statistical significance at the 1% level. Specifically, the coefficient of logging right is 501.7 in column (4), indicating a much higher marginal impact of harvesting quotas on carbon sequestration when devolved from higher-level authorities (i.e., the township in this case) to individual rural households. The specification of column (5) takes into consideration the possible correlation between rights and examines whether each right continues to exert influence after controlling for the effects of the others. Though the carbon sequestration impacts of ownership, tenure duration, and transfer rights are still statistically insignificant, the coefficient of own change slightly to 545.7, indicating that there is a sizable correlation between rights within the bundle.

Table 3.

Tenure rights and average carbon sequestration.

Besides, the regression results from columns (1) to (5) consistently indicate that, in addition to tenure-related factors, increases in labor age, education level, the share of off-farm employment, and household income are all significantly associated with higher levels of forest carbon sequestration. In contrast, the coefficients on climatic variables, i.e., average annual precipitation and temperature, are significantly negative across all model specifications, suggesting that the progressively warming climate conditions in southern China may already be exerting a suppressive effect on forest carbon sinks.

Table 4 further presents the effects of forest tenure on carbon sequestration by forest type. For mature forests, ownership and logging rights significantly enhance carbon sequestration, and the joint regression in column (5) confirms that the results hold after controlling for rights correlation. In contrast, the regression results for bush forests and young forests show considerable differences compared to mature forests. Columns (4) and (5) confirm a significant and positive effect of the logging right on the carbon sequestration of bush forests. Specifically, when decentralizing the logging right from the town to individual rural households, carbon consequence of the bush forest would increase by 710.2 gC/m2/year (column (5) of Table 4). In comparison, ownership can significantly improve carbon sequestration of young forests even after controlling for the correlation between rights.

Table 4.

Tenure rights and average carbon sequestration by forest types.

In general, official confirmation of ownership and issuance of certificates promote carbon sinks in newly planted forests, whereas clearer logging rights for operators would stimulate carbon sinks in both mature stands and shrubs. The reason may be that the clearer logging rights indeed encourage long-term management decisions of rural households, which will be explored in Section 4.3.

4.2. Rights Interaction and Carbon Sequestration

4.2.1. Rights Interaction and Average Carbon Sequestration

In Table 5, six pairwise interaction terms are introduced along with the four rights indicators to further explore the compound effects of different rights combinations on forest carbon sequestration. The results show that all interaction terms are statistically significant at the 1% confidence level, though the directions vary. Specifically, three combinations—logging right and ownership, logging right and duration, and ownership and duration—exhibit positive reinforcing effects. Specifically, in column (1), the interaction effect between logging rights and ownership is positive and significant. After controlling for their interaction effect, the effect of logging right on carbon sequestration still remains significantly positive, with a coefficient of 384.6 at the 1% level. However, the effect of ownership becomes insignificant once the moderating effect of logging rights is controlled. The results suggest that the positive effect of ownership on carbon sequestration works only when logging right can be guaranteed. Column (2) indicates a significantly positive interaction between logging rights and duration, which is theoretically sound as a longer tenure period amplifies the incentive effect of logging rights. However, in the absence of logging rights, extending the duration alone may negatively impact carbon outcomes—possibly due to distorted incentives caused by carbon emissions of overmature forests. The results in column (4) similarly reveal a positive reinforcing effect between ownership and duration. The interaction term is positive and significant, indicating that the combination of ownership and duration effectively enhances each other in promoting carbon sequestration. However, without a certain long-term tenure duration, official ownership would indeed decrease forest carbon sequestration, probably through incentives for deforestation.

Table 5.

Rights interaction and average carbon sequestration.

The interaction terms of transfer right with logging right, ownership, and tenure duration are all statistically significant but negative in columns (3), (5), and (6). Specifically, column (3) presents the interaction impacts between the logging right and the transfer right. Coefficients of logging right and transfer right are 405.9 and 110.5, respectively, at the 1% significance level. However, the interaction term (log × tran) has a significant coefficient of −164.6, indicating an effect of substitution when these two rights are combined. In scenarios where transferability is restricted, the marginal incentive effect of logging rights on forest carbon sequestration is 405.9 gC/m2/year, which is strongly positive and statistically significant. In contrast, when transfer right is unrestricted, the marginal effect of logging right decreases to 241.3 gC/m2/year—still positive, but much smaller. This suggests that the incentive effect of logging rights is stronger when transferability is limited. Column (5) reports a similar substitution relationship between ownership and transfer right. As the right to transfer increases, the marginal effect of ownership on forest carbon sequestration decreases from 81.4 to 6.5 gC/m2/year. Likewise, column (6) of Table 5 reports a significant and negative coefficient of the interaction between tenure duration and transfer right. As the right to transfer increases, the marginal effect of tenure duration on forest carbon sequestration decreases from 105.0 to −19.94 gC/m2/year. A possible explanation for the negative moderating effects of transfer right on each of the other three types of rights is that when transfer right is available, rural households may choose to transfer for rents instead of self-management. This, on average, decreases carbon sequestration as the large-scale operation of the lessee values more to the economic rotation period, where forests still have potential for carbon sinks.

Besides, after accounting for the interaction effects among tenure rights, the direction and magnitude of the estimated impacts of the control variables remain largely unchanged. The coefficients of socio-economic variables, such as age, education, off-farm, and income, remain significantly positive, whereas precipitation and temperature continue to exhibit a suppressive effect on forest carbon sequestration.

4.2.2. Rights Interaction and Average Carbon Sequestration by Forest Types

Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 report the interaction impacts of rights combinations on carbon sequestration by forest types. The results in Table 6 again show that the impacts of rights interactions on average carbon sequestration are mainly driven by the responses of mature forests. This is reflected in the fact that the influence directions of all interaction terms in Table 6 are not only consistent with those in Table 5, but also have comparable magnitudes. After controlling the interaction effects, the marginal impact of logging right exhibits a robust and positive impact in most specifications. In five out of the six columns of Table 6, the coefficient of logging right is significantly positive at the 1% level, ranging from 338.0 to 401.2, suggesting its fundamental role in promoting carbon sequestration. The positive but insignificant effect of logging right in column (2) (the specification with term log × dur) indicates that the premise for it to promote carbon deposition is a meaningful tenure duration. Once interaction impacts are controlled, ownership generally exhibits weak significance, appearing significant only in the specifications of its interaction with the tenure duration and transfer right, implying that its effect on carbon sinks of mature forests is completely conditional on logging right, whereas partially on the tenure duration and transfer right.

Table 6.

Rights interaction and carbon sequestration of mature forest stands.

Table 7.

Rights interaction and carbon sequestration of mature shrubs.

Table 8.

Rights interaction and carbon sequestration of young plantations.

Table 7 presents the impact of rights interaction on carbon sequestration of the bush forest. Based on the influencing direction of the interaction terms, the impacts of all rights combinations on shrub carbon sequestration are highly consistent with those of mature forests. The difference is that the promotion effects of rights interactions are much stronger on shrub carbon sequestration. This may be related to the relatively lower economic value and such looser rotation period of shrubs compared to forest stands.

Table 8 presents the effects of rights interactions on carbon sequestration of young stands. Quite different from both mature stands and shrubs, each of the six rights combinations shows an insignificant impact on the carbon sequestration of young forests, which are typically in their first three to four years of growing. After controlling for the interaction terms, the impact of ownership on carbon sequestration of young stands is still significant and positive except in columns (4) and (5), controlling for possible moderating effects of tenure duration and the transfer right. That is, ownership is the core force in stimulating carbon sinks in young plantations, and the other types of rights can hardly substitute ownership at the early stage of forest growth. This may relate to the possibility that rights mattering for the later stage, such as logging, occupy less consideration for afforestation/reforestation, at least in the beginning.

4.3. The Role of Forestry on the Tenure–Carbon Relationship

Table 9 displays regression results quantifying how different forestry management practices mediate the relationship between forest tenure and carbon sequestration outcomes. The first three columns are for mature forests, where column (1) presents the benchmark regression without forestry behavior and column (2) with an additional indicator measuring harvesting frequency and column (3) harvesting intensity. The regression coefficients of ownership and the logging right remain significantly positive at the 10% and 1% level, respectively, in each column, indicating that these two rights consistently exert robust positive effects on carbon sequestration of mature stands. The coefficient of harvesting frequency in column (2) is statistically insignificant, whereas that of harvesting intensity in column (3) is significant at the 1% level, with a coefficient of −2.5. This suggests that harvesting intensity rather than frequency is the channel through which forest tenure shapes carbon sequestration of mature stands. Specifically, the coefficient of logging right declines from 517.9 in column (1) to 457.7 in column (3), a decrease of approximately 11.6% whereas the marginal impact of ownership remains almost unchanged in magnitude. That is, a more devolved logging right decreases harvesting intensity, which in turn increases carbon sequestration of mature stands. Besides, consistent with the previous findings, logging rights exert a greater incentive for harvesting intensity reduction than ownership throughout this process. A possible explanation is that more accessible logging rights reduce harvesting uncertainty and institutional transaction costs, which in turn mitigate farmers’ incentives to engage in one-off, high-intensity harvesting. This encourages a longer-term management perspective and more carbon-friendly harvesting strategies.

Table 9.

The role of farmers’ actions on the tenure–carbon relationship.

The regression results of bush forests (the middle panel of Table 9) mirror those of the mature forest stands. The benchmark regression in column (1) shows that both logging right and transfer right have significantly positive carbon-sinking effects. Though the coefficients of harvesting frequency and intensity are insignificant in columns (2) and (3), the coefficient of logging right decreases from 710.2 to 675.9 and 569.9, respectively, with a reduction of approximately 4.8% and 19.7%. This suggests that harvesting intensity serves as a sizable channel through which logging rights affect carbon sequestration of bush forests. Given their shorter growth cycles and stronger regeneration capabilities, bush forests are more sensitive to harvesting behavior. The ease of access to harvesting may reduce rural households’ tendency toward high-intensity harvesting, allowing for more systematically planned harvesting practices that promote carbon sequestration.

The regression results for young forests are reported in the right panel of Table 9. Columns (2) and (3) introduce planting frequency and planting intensity, respectively, in addition to the benchmark regression in column (1). The coefficient of ownership remains significantly positive at the 1% level in all columns, reaffirming the dominant role of ownership within the tenure bundle in promoting carbon sequestration of new plantations. The coefficient for planting frequency is 14.8 at a significance level of 5%, while the coefficient for planting intensity is positive but insignificant, indicating that planting frequency rather than intensity contributes significantly to carbon sequestration of young forests. The coefficient of ownership decreases from 35.4 in column (1) to 32.8 in column (2), with a reduction of approximately 7.3%. It reveals that the frequency of afforestation/reforestation behaviors can partly explain the carbon-promoting impact of ownership on young stands.

5. Conclusions

This study constructs a panel dataset covering the period from 2000 to 2019 by integrating satellite observations, policy and statistical documents, and household surveys. Using two-way fixed effects models, interaction effect models, and mediation effect models, the study systematically evaluates the mechanisms through which forest tenure rights influence forest carbon sequestration in China. The empirical results can be summarized in three key aspects. (1) Logging right is consistently associated with higher levels of carbon sequestration, particularly in mature and bush forests. This finding aligns with previous studies suggesting that secure tenure and reliable revenue expectations incentivize greater forest investment [20,25]. (2) The interaction effects indicate that bundles of rights can either reinforce or undermine carbon outcomes. This provides empirical support for the view that disentangled assessment of individual rights, as is common in applications of the property rights bundle theory, may overlook the cross-effects among rights [2]. (3) Mediation analyses reveal that devolved tenure rights significantly reduce logging intensity and promote afforestation/reforestation frequency, thereby contributing to carbon sinks. These findings are consistent with broader literature indicating that tenure security fosters more sustainable land use practices [40]. (4) In addition, socioeconomic and climatic variables also have significant impacts on forest carbon sinks.

With the ongoing trends of population aging and non-agricultural transformation in China, long-term growth in forest carbon sinks can be anticipated; however, the suppressing effect of global warming on forest carbon sinks still warrants close attention. From a policy perspective, the empirical results suggest that streamlining administrative procedures—particularly through simplifying the application process for logging rights—can encourage sustainable investment and thereby enhance carbon sequestration. Tenure policies should also be tailored to different forest types: for mature and shrub forests, optimizing the synergy among tenure rights (e.g., aligning harvesting rights with conservation goals) is essential, while for young plantations, ensuring ownership integrity is crucial to support management during the early growth phase. Although this study is grounded in the Chinese context, the findings have broader implications. For countries undergoing forest tenure reforms—such as Brazil and Ghana [7,10]—it is essential to identify, within their own local contexts, the specific bundles of rights that contribute to carbon sequestration and to quantify the potential trade-offs among them, with particular attention to the heterogeneity across forest types.

Last but not least, it should be acknowledged that the empirical analyses are constrained by data limitations. Due to the substantial labor and resource requirements for interpreting land use classification imagery, forest types can only be distinguished as mature forests, young plantations, and shrublands. In addition, because of the temporal limitations of the NPP satellite, observations are available from the year 2000 onward. These constraints make it difficult for the empirical analysis to fully capture the long-term impacts of tenure reform, particularly for tree species with long rotation periods. However, short-term carbon sink responses to tenure reform—especially those driven by changes in logging and/or reforestation activities—can still be observed, as demonstrated in Section 4.3. Future research incorporating plot-level surveys may allow for more precise identification of tree species and stand ages, thereby enabling a more accurate evaluation of the long-term carbon sequestration effects of different tenure bundle arrangements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and W.H.; methodology, Y.L.; software, L.L. and Y.Z.; validation, Y.L. and L.L.; formal analysis, L.L. and Y.Z.; investigation, L.L. and Y.Z.; resources, Y.L. and W.H.; data curation, L.L. and Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L. and Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education of China, grant number 19YJC790075, the National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 20CGL030, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number SK2025087.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Ying Lin is a Tang Scholar at Xi’an Jiaotong University. She acknowledges the financial support from the Cyrus Tang Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Friedlingstein, P.; Jones, M.W.; O’sullivan, M.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Peters, G.P.; Peters, W.; Pongratz, J.; Sitch, S.; Le Quéré, C.; et al. Global carbon budget 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1783–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, T.A.; Lindeskog, M.; Smith, B.; Poulter, B.; Arneth, A.; Haverd, V.; Calle, L. Role of forest regrowth in global carbon sink dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4382–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, S.; Streck, C.; Obersteiner, M.; Frank, S.; Griscom, B.; Drouet, L.; Fricko, O.; Gusti, M.; Harris, N.; Hasegawa, T.; et al. Contribution of the land sector to a 1.5 °C world. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Yin, R. A primer on forest carbon policy and economics under the Paris Agreement: Part I. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 132, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Cao, R.; Malhi, S.S. Changes of vegetation carbon sequestration in the tableland of Loess Plateau and its influencing factors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 22160–22172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, S.; Gong, Z.; Gu, L.; Deng, Y.; Niu, Y. Driving forces of the efficiency of forest carbon sequestration production: Spatial panel data from the national forest inventory in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchelle, A.E.; Cromberg, M.; Gebara, M.F.; Guerra, R.; Melo, T.; Larson, A.; Cronkleton, P.; Börner, J.; Sills, E.; Wunder, S.; et al. Linking forest tenure reform, environmental compliance, and incentives: Lessons from REDD+ initiatives in the Brazilian Amazon. World Dev. 2014, 55, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, J.D. Carbon sequestration in Africa: The land tenure problem. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhatre, A.; Agrawal, A. Trade-offs and synergies between carbon storage and livelihood benefits from forest commons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 17667–17670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansanga, M.M.; Luginaah, I. Agrarian livelihoods under siege: Carbon forestry, tenure constraints and the rise of capitalist forest enclosures in Ghana. World Dev. 2019, 113, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Ma, G.; Tong, L. How policy instruments affect forest cover: Evidence from China. For. Policy Econ. 2025, 172, 103455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y. Devolution of tenure rights in forestland in China: Impact on investment and forest growth. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 154, 103025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E.; Holland, M.B.; Naughton-Treves, L. Does secure land tenure save forests? A meta-analysis of the relationship between land tenure and tropical deforestation. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 29, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, S. Has China’s new round of collective forest reforms caused an increase in the use of productive forest inputs? Land. Use Policy 2017, 64, 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.T.; Yi, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xu, J. Tenure security and investment effects of forest tenure reform in China. In Land Tenure Reform in Asia and Africa: Assessing Impacts on Poverty and Natural Resource Management; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 256–282. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Xu, J.; Xu, X.; Yi, Y.; Hyde, W.F. Collective forest tenure reform and household energy consumption: A case study in Yunnan Province, China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 60, 101134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Hyde, W.F. China’s second round of forest reforms: Observations for China and implications globally. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 98, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Xu, J. Forest land rights, tenure types, and farmers’ investment incentives in China: An empirical study of Fujian Province. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2013, 5, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sarkar, A.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Hasan, A.K.; Meng, Q.; Hossain, M.S.; Rahman, M.A. Evaluating the impact of forest tenure reform on farmers’ investment in public welfare forest areas: A case study of Gansu Province, China. Land 2022, 11, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.B.; Liu, C. The effect of forestland fragmentation and tenure incentive on the allocation of forest production input. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 1771–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.E. Property Is Not Just a Bundle of Rights. Econ J. Watch. 2011, 8, 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- Schlager, E.; Ostrom, E. Property-rights regimes and natural resources: A conceptual analysis. Land Econ. 1992, 68, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Berck, P.; Xu, J. The effect on forestation of the collective forest tenure reform in China. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 38, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Uusivuori, J.; Kuuluvainen, J. Impacts of economic reforms on rural forestry in China. For. Policy Econ. 2000, 1, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Impact of property rights reform on household forest management investment: An empirical study of southern China. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 34, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Innes, J.L. The implications of new forest tenure reforms and forestry property markets for sustainable forest management and forest certification in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 129, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, H. The Impact of Collective Forest Tenure Reform on Forest Carbon Sequestration Capacity—An Analysis Based on the Social–Ecological System Framework. Land 2023, 12, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Peng, R.; Liao, W. Does Collective Forest Tenure Reform Improve Forest Carbon Sequestration Efficiency and Rural Household Income in China? Forests 2025, 16, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Hatab, A.A.; Ha, J. Effect of forestland tenure security on rural household forest management and protection in southern China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickler, M.M.; Huntington, H.; Haflett, A.; Petrova, S.; Bouvier, I. Does de facto forest tenure affect forest condition? Community perceptions from Zambia. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 85, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.L. Effect of land tenure on forest cover and the paradox of private titling in Panama. Land. Use Policy 2021, 109, 105632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R.H. The problem of social cost. J. Law Econ. 1960, 3, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demsetz, H. Towards a Theory of Property Rights. Am. Econ. Rev. 1967, 57, 347–359. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Kebede, B.; Martin, A.; Gross-Camp, N. Privatization or communalization: A multi-level analysis of changes in forest property regimes in China. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 174, 106629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayer, J.; Sun, Z.; Müller, D.; Munroe, D.K.; Xu, J. Analyzing the drivers of tree planting in Yunnan, China, with Bayesian networks. Land. Use Policy 2014, 36, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wen, T. Macroeconomic fluctuations and collective forest rights reform of China: Systematic transitional analysis on “Divide or Cooperate” path of three collective forest rights reforms of China after 1980’s. China Soft Sci. 2009, 24, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Zhu, J. The evolution of legal texts of the “forest tenure certificate” and the scope of rights it certifies. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2014, 34, 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y. Institutional Reform of Collective Forest Property Rights and Forest Transfer in Jiangxi Province. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.J.; Xu, J.W.; Zhang, H.X. Can the forest logging quota management system protect forest resources? Chin. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 26, 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Qu, M.; Liu, C.; Yao, S. Land tenure, logging rights, and tree planting: Empirical evidence from smallholders in China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 60, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Running, S.W.; Zhao, M. Daily GPP and annual NPP (MOD17A2/A3) products NASA Earth Observing System MODIS land algorithm. In MOD17 User’s Guide; MODIS Land Team: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2015; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Zhuang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, X. Study on spatial pattern of land-use change in China during 1995–2000. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2003, 46, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Kuang, W.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, R.D.; Yan, C.Z.; Yu, D.S.; Wu, S.X.; et al. Spatial patterns and driving forces of land use change in China during the early 21st century. J. Geogr. Sci. 2010, 20, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).