1. Introduction

Forest ecosystem services (FESs) serve as a vital foundation for human well-being and are currently facing unprecedented global threats [

1]. Forests not only provide supply services such as timber but also perform critical functions such as climate regulation, soil and water conservation, and biodiversity maintenance [

2]. However, global forest cover continues to decline. Over the past 60 years, global forest area has decreased by 81.7 million hectares (approximately 10% larger than the entire island of Borneo), with forest loss (437.3 million hectares) exceeding forest restoration (355.6 million hectares) [

3]; broken down by 20-year intervals, forest loss shows different trends, with a net decrease of 129 million hectares between 1960 and 1980, 159 million hectares between 1980 and 2000, and 129 million hectares between 2000 and 2020 [

4]. This loss not only threatens the achievement of climate change mitigation targets but also poses a serious challenge to biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. To address this challenge, the international community has adopted various initiatives, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement, to mitigate forest loss and promote forest restoration.

In fact, when forest ecosystems are damaged, the multidimensional services they provide often cannot be restored in the short term, and some losses are irreversible [

5], posing a severe challenge to traditional judicial remedies. The United Nations Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) defines ecosystem services as the benefits people receive from ecosystems, categorized into four types: provisioning services, regulating services, cultural services, and supporting services [

6]. In the National Forest Management Plan (2016–2050) issued by the National Forestry Administration of China in 2016, the FESs were further categorized into four types: forest product supply, ecological protection and regulation, ecological culture, and ecosystem support [

7]. The National Forest Management Plan (2016–2050) has achieved remarkable successes during 2016–2025, including an increase in the national forest coverage rate from 21.66% to 24.02%, and the successful rehabilitation of more than 30 million hectares of degraded forest land through key projects such as ‘Returning Farmland to Forests’. In addition, the plan promotes the construction of 10 national forest city clusters, with a 15% increase in carbon sink capacity compared to the baseline period. Forest Ecosystem Service Function Assessment Specifications (GB/T 385822020) uses 18 indicators, including soil conservation, forest nutrient retention, water conservation, carbon sequestration and oxygen release, air purification, forest protection, biodiversity conservation, forest product supply, and forest health and wellness, to assess the FESs [

8]. At the international level, the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021–2030) calls for global collaboration to reverse ecosystem degradation. Typical examples include the European Union’s Natura 2000 network, which protects more than 18 percent of terrestrial habitats and strengthens biodiversity corridors, and the U.S. Forest Service’s Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP), which has restored 2.8 million hectares of degraded forests since 2010. China has made remarkable achievements through the Returning Cultivated Land to Forestry Project launched in 1999, which by 2020 will have restored 28 million hectares of fallow land, increased forest coverage by 3.3 per cent, and sequestered 2.6 billion tons of carbon. On this basis, the Master Plan for Major Projects for the Protection and Restoration of Nationally Important Ecosystems (2021–2035) aims to achieve the target of 30 per cent forest cover by 2035 through integrated watershed management and the construction of biodiversity corridors, which will provide a key reference for global forest governance. In addition, by organizing and implementing the Green Great Wall project, China has scientifically protected 538 million mu of sandy land, effectively managed 118 million mu of sandy land, significantly increased the forest coverage rate of the Green Great Wall project area, and made a major breakthrough in desertification prevention and control [

9], and through the implementation of the natural forest resource protection project, the forest stock of the northeastern forest area has increased by 40 million cubic meters, and the amount of sediment in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River has been reduced by 42% [

10]. With the help of six major ecological forestry projects, including natural forest protection, returning farmland to forests, the Three-North Protective Forests, the Yangtze River Protective Forests, the treatment of Beijing–Tianjin wind and sand sources, wildlife protection, and the construction of fast-growing and productive forest bases, China has completed the creation of forests of 4.446 million hectares, the planting of grass to improve 3.224 million hectares, and the treatment of sandy and rocky desertified land of 2.025 million hectares by 2024 [

11]. These projects are not only highly effective in ecological restoration but also provide strong support for realizing the goal of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality and building a beautiful China, and their innovative models provide an important model for global ecological restoration.

Traditional environmental damage judicial remedies primarily rely on monetary compensation and injunctions, which are relatively effective in addressing quantifiable direct economic losses [

12]. However, these mechanisms exhibit significant limitations in compensating for losses of FESs. Many important ecosystem services, such as biodiversity conservation and cultural value, are difficult to accurately monetize. Traditional compensation mechanisms often underestimate or overlook these losses, and monetary compensation cannot directly restore damaged ecological functions, while injunctions can prevent further damage but cannot repair existing harm [

13]. More critically, FESs exhibit long-term and complex characteristics, with their losses often involving disruptions to ecological processes and the breakdown of ecological relationships. These impacts may persist for decades or even longer, far exceeding the timeframe of traditional judicial procedures [

14]. In China’s judicial practice, there are three main categories: one is the neglect of indirect ecological losses; for example, in (2020) Qian 03 Min Chu 391, where commercial logging led to forest destruction, the court only calculated compensation based on the market value of timber and did not incorporate the loss of biodiversity; and in (2024) Yue 0232 Xing Chu 61, where the judgment was based on the cost of land reclamation to account for compensation but ignored the long-term impact of habitat fragmentation on gene flow, leading to a decline in the resilience of regional ecosystems. In the case of (2024) Yue 0232 Xing Chu 61, compensation was calculated on the basis of land reclamation costs, but the long-term impact of habitat fragmentation on gene flow was ignored, leading to a decline in the resilience of the regional ecosystem. Secondly, long-term cumulative losses are ignored. In (2020) Hei 75 Xing Zhong 14, the court set a three-year care period and compensated only according to the current carbon sink, ignoring the cumulative carbon losses during the period; in (2022) Qian 03 Min Chu 291, compensation was based on immediate landscape restoration costs and did not quantify the loss of cultural service flows. Thirdly, confusing service flow value with stock value, in (2024) Gan 0821 Min Chu 190, the court compensated on the basis of timber stock value but ignored annual water regulation loss and did not calculate its flow value; in (2025) Min 08 Min Zhong 193, ecological damage compensation covered only forest stock, but forest recreation service flow was not included.

Against this backdrop, China, as a country with significant forest resources, faces enormous economic development pressures, providing a unique testing ground for the practical application of restorative justice principles in environmental protection. In recent years, China has actively explored the application of restorative justice principles in environmental judicial reform. This approach emphasizes compensating for environmental damage through actual ecological restoration rather than relying solely on economic compensation [

15]. Since 2015, China has actively explored and institutionalized the application of the concept of restorative justice in its environmental justice reform, and during this decade-long period, China’s environmental public interest litigation system has developed rapidly, and the system of compensation for ecological and environmental damages was formally established in 2018. The institutional innovations that have evolved since 2015 have provided a critical time dimension and substantive support for the implementation of restorative justice. The restorative justice shift reflects a profound recognition of the limitations of traditional environmental justice and represents an institutional response to China’s ecological civilization construction. China has established over 2800 specialized environmental courts and organizations, consolidating the judicial functions for criminal, civil, and administrative environmental resource cases under environmental resource courts. China’s environmental public interest litigation system has developed rapidly, with over 400,000 environmental public interest litigation cases handled by procuratorial organs at all levels nationwide [

16], and the establishment of an ecological and environmental damage compensation system. These institutional innovations provide important support for the implementation of restorative justice. However, despite the theoretical potential of restorative justice to compensate for losses of FESs, there is currently a lack of systematic empirical research on its actual effectiveness, particularly in countries like China that are actively implementing such measures. Existing studies primarily remain at the theoretical level or focus on case analyses, lacking in-depth examinations of the degree of alignment between restorative justice measures and losses of FESs, as well as the identification and analysis of systemic issues encountered during implementation.

Based on the above background, this study aims to systematically examine the actual performance of restorative justice in compensating for the loss of FESs through a qualitative analysis of Chinese judicial practices. On this basis, it proposes directions for improvement. This study is not only of great significance for improving China’s environmental justice system, but its experience and lessons are also of great reference value for other countries facing similar challenges. Through an in-depth analysis of Chinese judicial practices, this study aims to provide valuable experience and reference for the protection of FESs through judicial means on a global scale.

2. Theoretical Framework

The concept of restorative justice originated from a series of small-scale judicial experiments in Canada and the United States in the 1970s [

17]. After decades of development, restorative justice has been increasingly adopted by countries around the world into their domestic judicial practices. In the field of ecological and environmental protection, restorative justice emerges as a new judicial philosophy, whose core principles include repairing harm, restoring relationships, active participation of the responsible parties, and community involvement [

18]. Unlike the traditional punitive judicial model, restorative justice places greater emphasis on repairing the harm caused by illegal acts through concrete actions, emphasizing the constructive and forward-looking nature of responsibility [

19]. This is manifested through measures such as ecological restoration and environmental governance to compensate for environmental harm, rather than relying solely on traditional sanctions such as fines or imprisonment. These characteristics of restorative justice give it unique advantages in handling environmental damage cases, particularly when dealing with complex ecosystem damage, enabling it to better achieve the substantive goal of compensation for harm [

20]. Restorative justice measures can be categorized into behavioral measures, monetary measures, and contractual measures. For example, land reclamation, soil remediation, afforestation, and restocking in practice belong to behavioral measures, while compensating for ecological restoration costs or paying ecological restoration guarantees involve monetary measures, and signing agreements or commitments for ecological restoration belong to contractual measures.

A classification framework for forest ecosystem services provides a reference for understanding and assessing the effectiveness of restorative justice. Based on the framework of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), FESs can be categorized into four major types: provisioning services provided by wood and non-wood forest products, regulating services such as climate regulation and hydrological regulation, supporting services such as nutrient cycling and soil formation, and cultural services including recreational and leisure activities, spiritual and cultural values, and esthetic values. This classification framework not only helps comprehensively identify the various losses that forest destruction may cause but also provides a scientific basis for designing targeted restoration measures. When forest ecosystems are damaged, different types of service functions may be affected to varying degrees, and the difficulty and time required for their restoration also vary significantly. This requires restorative justice measures to be systematic and targeted.

Restorative justice exhibits distinct characteristics in environmental resource cases and demonstrates a high degree of intrinsic compatibility with compensation for forest ecosystem services. Its theoretical advantages are primarily manifested in several aspects. First, compared to monetary compensation, restorative justice places greater emphasis on substantive ecological restoration, enabling the direct repair of damaged ecological functions [

21], which aligns more closely with the functional characteristics of FESs. Second, restorative justice possesses adaptive management characteristics, enabling adjustments to restoration strategies based on the complexity and uncertainty of ecosystems [

19], which is crucial for addressing the dynamic changes in forest ecosystems. Third, restorative justice places greater emphasis on protecting collective interests, aligning with the public good attributes of FESs and better safeguarding the overall environmental rights of society [

22]. Fourth, restorative justice emphasizes long-term effects, which aligns with the long-term nature of FESs and contributes to achieving sustainable environmental protection [

23]. Judicial practice in the EU provides an important reference for functional compensation mechanisms. For example, the German Federal Constitutional Court’s 2021 ruling on the Climate Protection Act, which compels the government to set annual emission reduction targets by sector after 2030, directly links judicial intervention to the restoration of regulating services. France’s Ecological Damage Doctrine, on the other hand, recognizes the independent juridical status of biodiversity and carbon sinks, requiring courts to appoint multidisciplinary panels of experts to design compensation schemes. These cases show that the justice system can enforce the restoration of non-marketed ecosystem services through scientific assessments and legislative accountability, which is where China’s current restorative justice framework is weak.

Restorative justice views human society and the ecological environment as a community with a shared future, breaking free from the constraints of traditional “anthropocentrism.” It emphasizes equal protection for the public ecological environment, the environmental rights of contemporary people, and the survival and development of future generations and other biological species, striving for the unity of judicial outcomes, social outcomes, and environmental outcomes [

24]. Unlike traditional judicial systems, which are punitive in nature, restorative justice emphasizes “restitution for harm,” encouraging and guiding offenders to actively participate in damage restoration and environmental protection activities [

25]. The methods of assuming responsibility include behavioral measures such as replanting and reforestation, restocking and release, and land reclamation; monetary measures such as ecological restoration costs and ecological restoration guarantees; and contractual measures such as ecological restoration agreements and environmental protection commitments. Restorative justice advocates proactive judicial intervention throughout the entire process, from preventive measures before the fact, intervention during the incident, to post-incident supervision. This proactive approach breaks through the passivity of traditional justice and allows preventive measures to be initiated when there is a risk of significant damage to the ecological environment, rather than waiting for the damage to actually occur. Additionally, restorative justice mobilizes relevant stakeholders such as judicial authorities, administrative departments, professional technical units, and community organizations to collaborate in the environmental justice governance process [

26], achieving a “win–win” outcome—punishing violators, compensating victims, restoring damage, alleviating governance pressures on stakeholders, and transcending the traditional separation of criminal and civil, as well as civil and administrative, judicial systems. It integrates criminal, civil, and administrative liabilities to maximize ecological restoration. These characteristics make restorative justice highly compatible with forest ecosystem service compensation in multiple dimensions: the essence of forest ecosystem services is ecological function, and the goal of restorative justice—to restore damaged social relationships and enhance the overall quality of the ecological environment—aligns closely with the restoration objectives of forest ecosystem services [

27]. Restorative justice emphasizes long-term and sustainable outcomes, establishing institutional arrangements such as forest protection and long-term monitoring, which aligns with the long-term nature of FES restoration; the “principle of balance” in restorative justice requires comprehensive consideration of the complexity of ecological and environmental damage, the technical nature of restoration, and the long-term nature of recovery [

28], providing a framework for addressing the multidimensional, multi-scale, and non-linear characteristics of forest ecosystem services; based on ecological justice theory, restorative justice not only focuses on economic value losses but also places greater emphasis on the protection of ecological value, cultural value, and other diverse values, which corresponds to the multi-value system of FESs encompassing supply, regulation, support, and cultural services.

The institutionalization of restorative justice in China provides an important institutional backdrop for this study. In recent years, China has actively incorporated restorative principles into environmental resource adjudication, promoting the practice of restorative justice through a series of judicial interpretations and institutional innovations. Relevant judicial interpretations issued by the Supreme People’s Court have clarified the principles and methods of ecological and environmental damage compensation, providing a legal basis for restorative justice. The establishment of specialized adjudication bodies, such as the widespread establishment of environmental resource courts, has provided organizational guarantees for the professional implementation of restorative justice. Explorations of alternative restorative practices, such as off-site restoration and labor compensation, have enriched the implementation methods of restorative justice. These institutional efforts not only reflect China’s emphasis on environmental protection but also create favorable conditions for the application of restorative justice in forest protection.

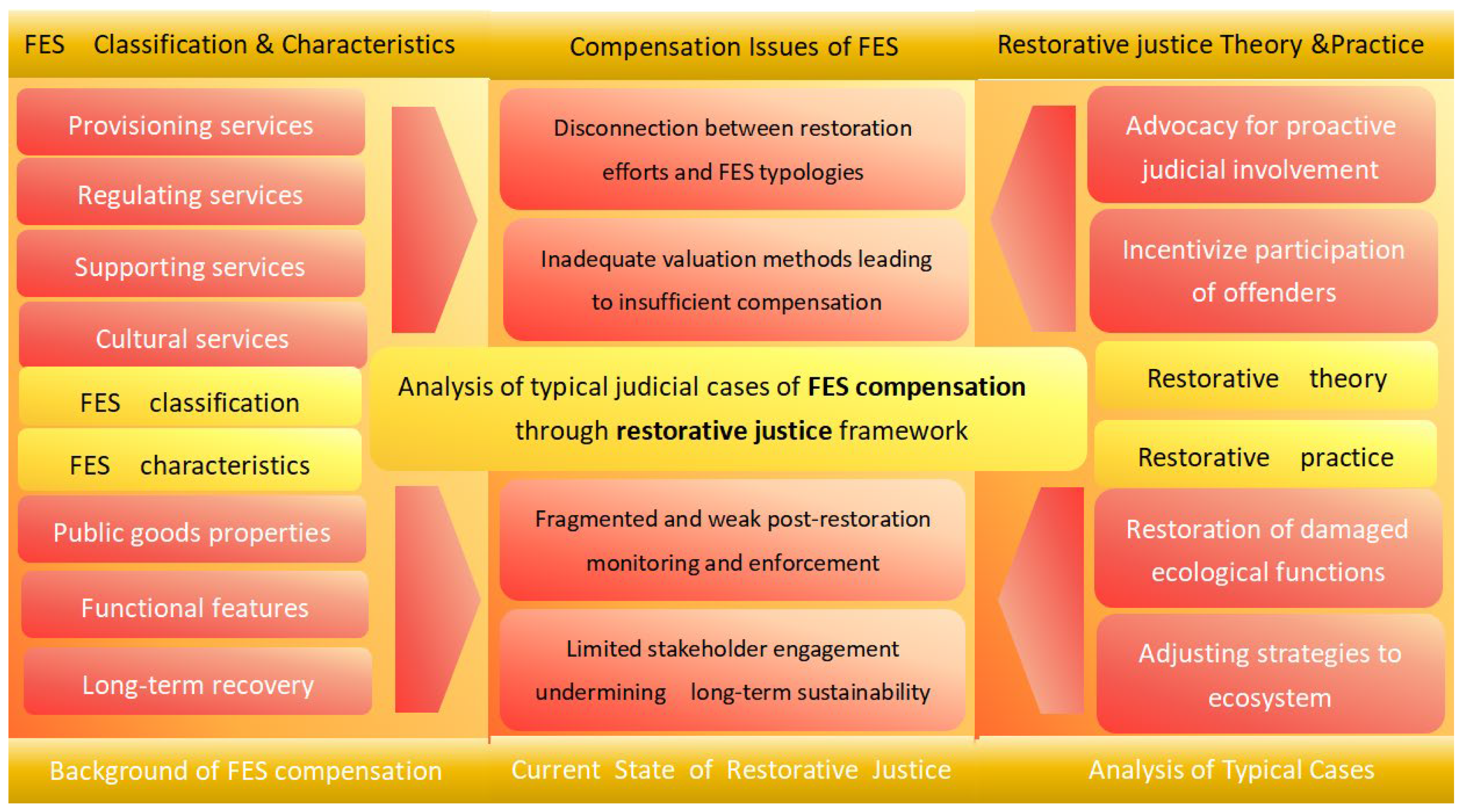

The core focus of this study is to examine the actual effectiveness and challenges of restorative justice in compensating for losses of FESs through an analysis of judicial rulings and practices. This study will revolve around the following core questions: To what extent do restorative measures in Chinese judicial practice cover various types of damaged FESs? Are existing mechanisms capable of effectively compensating for losses of FESs? How can a more scientific forest ecosystem service-oriented restorative justice pathway be constructed? Through in-depth exploration of these questions, this study aims to provide a scientific basis and policy recommendations for improving the restorative justice system and enhancing the effectiveness of forest ecosystem protection (

Figure 1).

3. Methods and Data Sources

This paper adopts a qualitative research methodology, including textual analysis of judicial cases and summarization of their constituent elements, focusing on understanding the logic, value trade-offs, institutional inertia, and potential contradictions embodied in the text of the court’s judgment. The textual analysis of the judicial cases includes the following aspects: in terms of FES loss determination, a careful analysis of how the text of the judgment describes and defines the damage caused by forest destruction, whether the text of the judgment explicitly mentions or implicitly deals with specific types of FESs, and how the judgment argues for the scope, extent, and nature of the loss. In terms of restorative measures, the text of the judgment was carefully read to analyze the restoration objectives, specific measures, and expected results proposed by the court and to analyze whether and to what extent the design of these measures responded to the FES damages identified by the court, and whether the selection of these measures was mainly based on legal provisions, expert opinions, or administrative practices. In terms of the enforcement and monitoring mechanism, analyze the provisions in the text of the judgment regarding the responsible parties, the supervisory parties, the acceptance criteria, the monitoring cycle, and the consequences of non-compliance, and pay attention to the scientific, operational, and institutional articulation of the judgment. In terms of the chain of argumentative reasoning, examine the reasonableness of the judgment’s argumentative restoration scheme, for example, analyze whether the judgment simply cites legal provisions, relies on appraisal reports, or elaborates on the principles of ecological restoration, as well as identifying potential value preferences reflected in the text.

In response to the generalization of case components, cross-case comparisons are made based on in-depth readings of individual cases. The focus is on identifying the following: patterns of differences in the scope of FES loss determination across cases, associations between types of restoration measures and types of losses, patterns of common flaws in the design of monitoring mechanisms, and patterns of typical logical limitations in judicial reasoning. On this basis, the results obtained are interpreted in the context of the theoretical framework of restorative justice and the institutional context of China’s environmental justice reform. Based on the problems exposed in the text and the dilemmas faced by the courts, the institutional root causes are explored.

The judicial cases selected for this paper were obtained from the Judicial Instruments Website (

https://wenshu.court.gov.cn/, accessed on 3 May 2025), the Beida Legal Information Network (

https://www.pkulaw.com/, accessed on 3 June 2025), and the People’s Court Case Bank Website (

https://rmfyalk.court.gov.cn/, accessed on 10 June 2025). In order to guarantee the representativeness of the samples and the validity of the analysis, the selection was based on the following criteria: the core dispute of the cases must involve the destruction of forest resources, including, but not limited to, logging, deforestation, reclamation, and forest fires, and the main text of the decisions explicitly adopts restorative judicial measures, such as in situ or out of situ restoration, alternative restoration, and compensation in lieu of labor, instead of purely financial compensation. It needs to be ensured that the cases can cover the major forest types and typical destruction situations in China and geographically cover different ecological regions such as the old-growth forest, secondary forest, plantation forest, and protected area. In terms of the type of damage, it includes different triggers such as commercial development, infrastructure encroachment, agricultural expansion, subsistence logging, etc. In terms of the scope of trial, it includes typical cases of environmental resources issued by the Supreme People’s Court, reference cases of provincial high courts, and judgments of grassroots courts, reflecting the whole picture of judicial practice. Finally, the data integrity quality rules; that is, the judgment documents need to be public and contain key information that can be analyzed: the factual determination of damage includes clear destruction, damaged area, FES loss description; the restoration program includes goals and specific measures. The implementation subject includes the implementation and supervision mechanism: acceptance criteria, supervision subject, and accountability provisions. Effectiveness tracking information includes acceptance report, third-party assessment data, and follow-up inspection records. In order to ensure the reliability and representativeness of the findings, we adopted multiple validation strategies: Hierarchical validation of case selection: we not only analyzed the judgments of the grassroots courts but also included the typical cases of the intermediate courts and the high courts, as well as the guiding cases issued by the Supreme People’s Court, to ensure the hierarchical completeness of the sample. Validation of balanced geographical distribution: The sample cases cover seven major geographical regions in China, including different climate zones, vegetation types, and levels of economic development, ensuring the universality of the study’s conclusions. Validation of continuity in a time span: The sample cases span from 2020 to 2025, covering an important period in the rapid development of China’s environmental justice system and reflecting the dynamic characteristics of the system’s evolution.

In the screening process, we screened judicial cases through core behavioral words, judicial procedure words, measure words, and loss words. The core behavioral words include forest destruction, forest theft, deforestation, deforestation, illegal occupation of forest land, and forest fire. The words of judicial process include environmental civil public welfare litigation, ecological and environmental damage compensation litigation, and restorative justice. Measures include ecological restoration, replanting and re-greening, off-site restoration, labor compensation, and stock enhancement. Loss words include ecological service function loss, ecological environment damage, etc. In total, 343 adjudication documents were obtained through screening, and the distribution characteristics of the adjudication documents are shown in

Table 1, and the index numbers of specific cases cited in the text are shown in

Table A1; all sample index numbers are shown in the

Supplementary Files.

5. Discussion

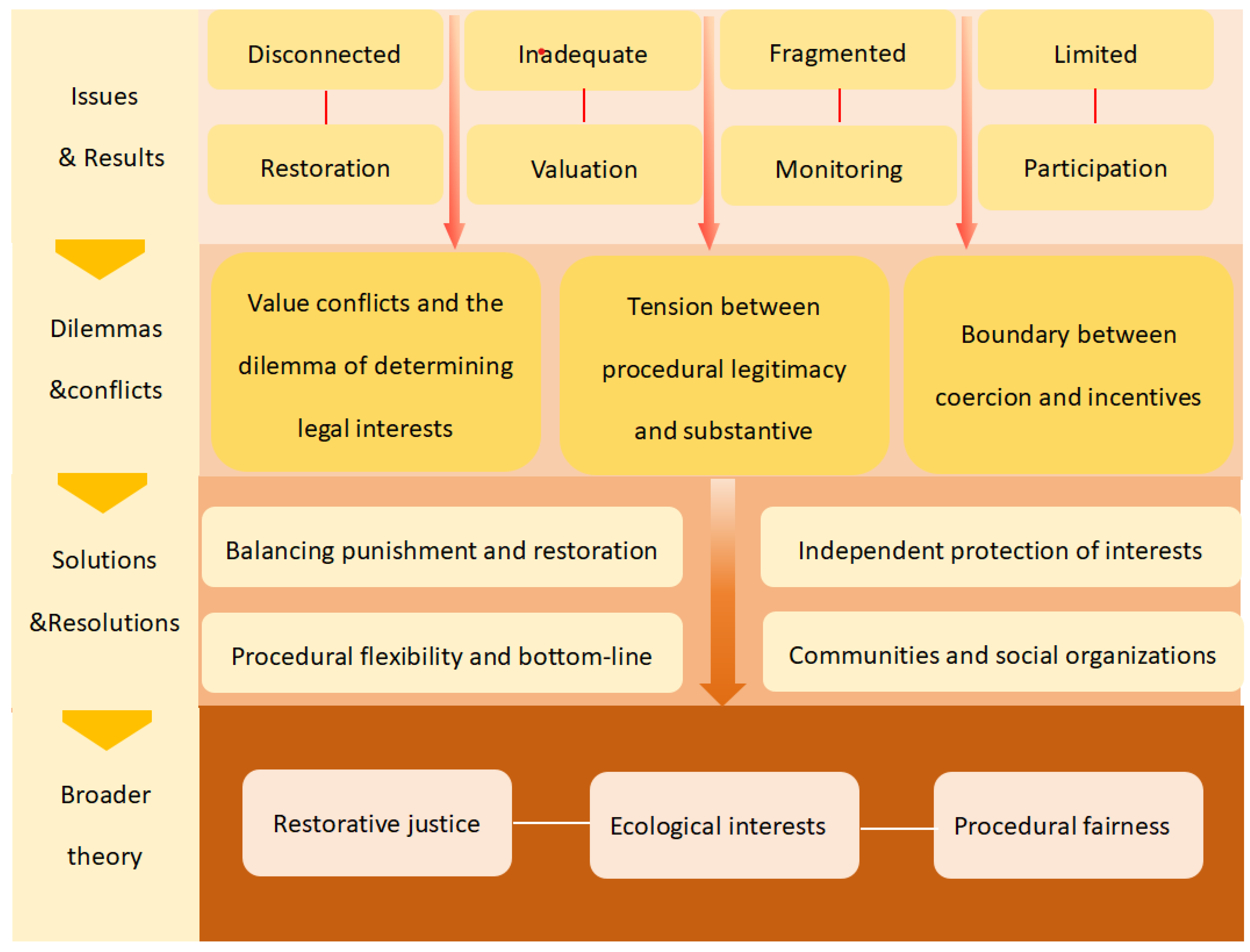

Through a qualitative analysis of 343 Chinese forest restoration judicial cases, it can be observed that while restorative justice provides a framework at the institutional level for compensating for losses of FESs, its practical effectiveness faces multiple systemic challenges. When addressing the complex subject matter of FESs, China’s restorative justice system still exhibits conflicts and mismatches in its institutional design and operational logic. These conflicts stem not only from technical operational limitations but also from the value tensions between restorative principles and traditional judicial frameworks, the challenges in recognizing the independence of ecological legal interests, and the balancing act between procedural fairness and the substantive effectiveness of restoration. It is imperative to explore potential reconciliation pathways and innovative directions to facilitate a paradigm shift in restorative justice from formal restoration to substantive functional recovery. Based on the issues related to forest ecosystem restoration cases under the restorative justice framework, we propose a comprehensive solution. The improved pathway for compensating FESs under the restorative justice framework is illustrated in

Figure 2.

5.1. The Value Conflict Between the Concept of Restorative Justice and Traditional Retributive Justice and Its Path to Reconciliation

The primary jurisprudential dilemma faced in China’s forest ecological restorative justice practice lies in the deep value conflict between restorative justice and traditional retributive justice. While traditional environmental justice emphasizes state-based punishment, restorative justice focuses on the actual restoration of damaged forest ecological legal interests. In forest cases, if punishment is overemphasized, ecological restoration may be neglected; if only restoration is talked about, the deterrent effect of the law may be weakened. The path to reconciliation lies in the construction of a judicial model that emphasizes both punishment and restoration. The core lies in the following: (1) Legislative parallelism: within the criminal framework, it is clear that ecological restoration responsibility is an independent obligation, coexisting with the penalty rather than substituting for it. (2) Dynamic convergence: establishing a mechanism for evaluating restoration effects; perpetrators who actively and effectively fulfill their restoration responsibilities may receive a reduction or exemption of their penalties within the range of statutory penalties and vice versa may receive an aggravation. This not only maintains the deterrent effect of justice through the retention of penalties but also guides the perpetrators to take the initiative to assume responsibility through the incentive restoration mechanism, substantially restoring the damaged ecological service functions of forests, and realizing the balance and unity of the two concepts of justice at the value level. Traditional environmental justice is centered on state-based justice, emphasizing retribution for environmental violations through administrative penalties, while restorative justice is oriented towards the restoration of harmed legal interests [

43]. This conflict is particularly evident in forest ecology cases: traditional justice focuses on the punishment of forest-destroying actors but neglects the actual restoration of forest ecosystem services. This difference in value orientation is rooted in different understandings of the concept of “justice”—the former equates justice with the reciprocity of punishment, while the latter understands justice as the substantive restoration of damage [

44].

In fact, in the case of forest restoration, the two views of justice are not diametrically opposed; on the one hand, the judge needs to be based on the specific circumstances of the parties and the relevant legal basis for its punitive measures to urge the perpetrator passive acceptance of the corresponding restoration of the type of punishment; on the other hand, the judge in the judgment should also encourage the perpetrator to take the initiative to make the restoration of forests or guide the criminal behavior of the stakeholders to determine the negotiation of forest restoration of these two types, the judge, according to the perpetrator of the forest restoration commitment, or the results of the final determination of punitive damages for the perpetrator. Therefore, it is necessary to build a dual-track judicial model that emphasizes both punishment and restoration. Specifically, the mechanism of parallel application of restorative and punitive measures should be clarified at the legislative level, and the responsibility for ecological restoration should be incorporated into the criminal liability system, but not as a substitute for due criminal punishment. At the same time, the establishment of the “restoration effect evaluation—penalty adjustment” dynamic convergence mechanism, according to the perpetrator, is carried out to fulfill the actual effect of ecological restoration responsibility in the statutory range of punishment for its corresponding adjustment to achieve retributive justice and restorative justice organic unity. In terms of procedure, restorative justice allows parties with an interest in the case to negotiate on a voluntary basis, and in the case of forest restoration, the content of the negotiation should include how to compensate for the loss of forest ecosystem functions, with the fundamental aim of restoring the supply service, regulation service, support service and cultural service functions provided by forests. This model not only maintains the deterrent function of justice but also incentivizes perpetrators to actively participate in ecological restoration, thus reconciling the two concepts of justice at the value level.

5.2. The Dilemma of Recognizing the Independence of Forest Ecological Legal Interests and the Innovation of Judicial Protection Paths

Another deeper jurisprudential issue in the current application of restorative justice in forest cases is the dilemma of recognizing the independence of ecological legal interests in forests. Traditional legal theory treats forests mainly as a carrier of property or public safety legal interests, while ignoring their attributes as independent ecological legal interests. Forest ecosystem service functions include multiple values such as climate regulation, soil and water conservation, and biodiversity maintenance, and the loss of these functions is often difficult to measure by traditional property damage or personal injury standards [

45]. This ambiguity in the identification of legal interests has directly led to problems such as inconsistent standards for assessing forest ecological damage and difficulties in selecting restoration measures in judicial practice. From the viewpoint of the object of forest ecological legal interests, the object of ecological protection interests, in general terms, refers to the ecosystem of the forest, specifically expressed as the functional benefits of the ecosystem of the subject and the ecosystem of the function of the form being carried out [

46]. The former forest is the ecosystem service value, indicating the utility of ecosystem function, and the latter is the ecological and physical carrier of forest ecosystem service utility. In terms of the subject of forest ecological legal interests, in the context of restorative justice, it should include two categories, the first category is the forest ecosystem itself, including living and non-living objects, the second category is human beings, in the traditional judicial context. Forest ecological interests of the “beneficiary subject” are only human beings, as a “service” ecosystem is entirely “service”. In the traditional judicial context, the “beneficiary subject” of forest ecological benefits is only human beings, and the ecosystem as the “service object” is completely in the position of the “service object” and is treated as an object. The theory of restorative justice encourages a greater “vitalization” of the “beneficiary subject” and a weakening of the artificial servitude of traditional social law, which treats the ecosystem itself as an “object”.

Traditional law has primarily viewed forests as property or resources, with damage measured in terms of economic value or administrative violations, ignoring their inherent value as independent ecosystems that provide regulatory, supportive, cultural, and other services. This cognitive ambiguity has led to confusing assessment standards and a disconnect between restoration measures and functional loss in judicial practice. The solution lies in the following: Firstly, establishing the principle of independent protection of ecological legal interests in legislation and making it clear that the FES function of forests itself is an independent type of legal interest protected by law. Secondly, to formulate specialized standards and assessment systems for the identification of functional damage, beyond the value of timber, to scientifically quantify the loss of carbon sinks, the damage to biodiversity, and the decline in water source regulation function. Third, to establish a function-oriented judicial protection mechanism: judges order targeted restoration measures based on the specific type of FESs damaged, rather than uniform tree planting. Finally, strengthening the judicial appraisal support, which requires that professional organizations must carry out scientific assessments of the loss of FES function. Through these innovations, justice can truly shift from protecting forest resources to protecting the service functions of forest ecosystems.

Meanwhile, to solve this dilemma, it is necessary to establish the principle of independent protection of ecological legal interests from legal theory. Forest ecosystem service function should be explicitly regarded as an independent type of legal interest in the legislation, and a special ecological damage identification standard and assessment system should be formulated. A function-oriented judicial protection mechanism should be established, i.e., with the restoration of forest ecosystem service functions as the core objective, and diversified measures such as replanting and re-greening, alternative restoration, and ecological compensation should be comprehensively applied. In addition, a judicial appraisal system for damage to ecosystem services should be introduced, so that professional organizations can scientifically assess the loss of forest ecosystem services and provide an objective basis for the selection of restorative measures. Through these institutional innovations, independent and adequate protection of forest ecological legal interests can be realized at the judicial level.

5.3. Construction of a Mechanism for Balancing the Tension Between Procedural Due Process and Substantive Justice

The applicability of the concept of restorative justice in dealing with cases involving forest resources has always been accompanied by a contradiction, namely, the irreconcilable tension between the guarantee of procedural due process and substantive restoration outcomes. This tension is manifested in a structural dilemma: the core operational mechanism of restorative justice, i.e., the path of relying on non-confrontational methods such as negotiation and mediation to seek consensus and restorative solutions for all parties to a conflict, while enhancing the efficiency of resolution and situational adaptability, inevitably impacts on procedural norms and the predictability of outcomes maintained by the traditional justice model. Forest ecological restoration is highly specialized, long-term and territorial, requiring the incorporation of local knowledge, expert opinions, and dynamic adjustments, but this may conflict with the rigidity of traditional litigation procedures, resulting in the best restoration solutions not being able to be put in place or delayed due to procedural constraints. To address this tension, an institutional framework combining procedural flexibility and bottom-line control should be constructed: (1) Graded and categorized procedures: different procedural paths should be set according to the complexity of the damage, and the process of non-complex cases should be simplified. (2) Establishment of procedural bottom-line principles: the core includes voluntariness, expert participation, public knowledge, and supervision to ensure basic justice. (3) Compound safeguard mechanism: adopt the model of judicial confirmation, administrative supervision, and social supervision. (4) Giving judges moderate procedural discretion: allowing judges to make necessary adjustments to procedures in individual cases in order to safeguard the scientific nature of restoration. This framework aims to strike a balance between the effectiveness of restoration and the basic standardization and acceptability of the procedure. While traditional procedural rules aim to guarantee the rights of participants and the fairness and transparency of adjudication through standardized processes, the flexibility of restorative processes may lead to the dilution of such guarantees, especially in cases with asymmetric information or imbalanced power relations [

47]. This tension is particularly tangible in the forest ecosystem restoration cases in this study. Forest ecosystems have a highly complex inner structure, dynamic succession laws, and close dependence on specific geographical environments, and any program development aimed at restoring their ecological functions is essentially a professional process that requires in-depth integration of local ecological knowledge [

48], consideration of long-term restoration trajectories, and repeated dynamic adjustments, implying the exclusion of rigid, uniformly applicable procedural rule bindings, and a judicial process that excessively adheres to the strict formal requirements of the traditional judicial process, such as fixed deadlines for lawsuits, restrictions on the types of evidence, or complicated court hearings is likely to delay the timing of restoration, limit the full involvement of experts and local communities in program design, and ultimately make it difficult for the most ecologically sound and targeted restoration measures to take root.

Restorative justice takes repairing damage and restoring balance as its fundamental purpose, presenting the characteristics of “result-oriented” or “repair-oriented”, and its core lies in achieving concrete and effective ecological restoration results [

49]. On the contrary, traditional justice emphasizes the universality of formal justice, and its operation revolves around the practical implementation of the established procedural rules, which has the attribute of “procedure-oriented” or “rule-oriented”. When these two models with different philosophical foundations and legal values converge in complex forest ecological restoration scenarios, the conflict between procedural legitimacy and substantive restoration effectiveness becomes a central issue that is difficult to avoid in practice.

To resolve this tension, it is necessary to build an institutional framework that combines procedural flexibility and bottom-line control. Specifically, it includes the following: establishing a hierarchical and classified procedural application mechanism, setting up different procedural paths according to the severity and complexity of the damage to forest ecosystem functions, establishing the bottom-line principles of restorative justice, such as the principle of party voluntariness, the principle of expert participation, and the principle of public supervision, etc., so as to ensure the basic fairness of the procedure. A composite safeguard mechanism of judicial confirmation, administrative supervision, and social supervision has been created to not only guarantee the scientific nature and feasibility of restoration programs but also to maintain the transparency and credibility of the process. At the same time, judges are given procedural discretion in forest restoration cases, allowing them to make appropriate adjustments to procedures in accordance with the actual needs of forest ecosystem restoration, so as to achieve a dynamic balance between procedural legitimacy and substantive justice.

5.4. The Mandatory Boundaries of Restorative Measures and the Jurisprudential Reconstruction of Incentives

The fourth jurisprudential dilemma faced by restorative justice in responding to forest ecology cases is the difficulty of defining the mandatory boundaries of restorative measures themselves. The theoretical framework of restorative justice usually places voluntary participation as the cornerstone of the legitimacy of restorative processes, emphasizing that the intrinsic motivation and sincere repentance of the parties, especially the responsible parties, are the key driving forces for repairing relationships and achieving substantial ecological restoration [

50]. However, the limitations of relying purely on voluntariness are revealed when the central concern of the case turns to the damaged forest ecosystem, an environmental good with high public good properties and ecological value that is difficult to quantify instantaneously, but which is critical to long-term overall well-being. In practice, a purely voluntary framework may lead to the restoration of areas of specific ecological significance or urgent restoration needs, whose restoration responsibilities fall into a substantive state of failure due to the lack of motivation or lack of economic and technical capacity of the responsible parties, thus reducing the ecological justice pursued by restorative justice to a castle in the air [

51]. If coercion is overemphasized or imposed in order to ensure that the goal of ecological restoration is achieved, such as setting harsh and non-negotiable restoration obligations with the help of the strong intervention of public power, it will easily slip into another risk of eroding the essence of restorative justice. Such coercion, if unchecked, may not only ignore the specific context and capacity of the perpetrator and inhibit the generation of his or her intrinsic sense of responsibility but may also alienate the restorative process, which is originally aimed at repairing social relations and the environment and focuses on education and transformation, into a kind of hidden retributive punishment under the guise of “restoration” [

52]. Instead of contributing to the long-term stability of reconciliation and environmental restoration, the result may be a departure from the core values of participatory, dialogical, and future-oriented restorative justice.

The essence of this dilemma is far more than a simple procedural issue and reflects the legal conflict between the concept of restorative justice in dealing with the protection of the integrity and function of forest ecosystems and the rights of the individual parties, especially their free will to act. How to establish legal concepts and institutional design that do not sacrifice the public interest requirements of ecological restoration effectiveness but also do not fall into the individual freedom and dignity of the coercive trap, really needs to break through the simple dichotomy. To solve this problem, we need to build a “bottom line mandatory + full incentives” system. First of all, clear ecological restoration of the mandatory bottom line; that is, to cause ecological damage to forests, the perpetrator has a non-exempt restoration obligation, and such obligations have legal and mandatory status. Secondly, in the choice of restoration methods, to give the actors full autonomy, allowing them to choose among a variety of restoration programs will stimulate their initiative to restore their enthusiasm. Once again, a perfect incentive mechanism should be established, including the reduction or exemption of criminal liability, the reduction in administrative punishment, and credit repair, so that the perpetrators can obtain substantial benefits from the fulfillment of their ecological restoration responsibilities. Finally, the creation of the “ecological restoration fund” system, the perpetrators who really cannot afford to bear the responsibility of restoration can pay the restoration fund to fulfill their obligations, ensuring that the forest ecological restoration goal is achieved. This system design not only maintains the rigid requirements of ecological restoration but also retains the flexible character of restorative justice.

To summarize, purely voluntary measures may result in key ecological restoration due to the unwillingness or inability of the responsible person; excessive coercion may alienate the essence of restorative justice and degenerate into punishment in disguise. There is a need to build the bottom line of mandatory and full incentives for the reconstruction of the system of jurisprudence: (1) Clear mandatory bottom line: the legislation provides that the perpetrators of ecological damage to forests have a non-exempt legal obligation to repair to ensure the bottom line of public interest. (2) The right to choose the mode of restoration: the actor is given the right to choose the mode of fulfillment of the obligation to stimulate its initiative. (3) Establishment of adequate incentive mechanism: link the effect of the perpetrator’s fulfillment of the restoration responsibility with substantive benefits such as reduction in criminal liability, reduction in administrative punishment, and credit repair, to create a strong incentive. (4) Create an ecological restoration fund: for those responsible, who really cannot afford restoration, they are allowed to pay into the fund to be fulfilled by a professional organization on their behalf to ensure that the restoration goal is not defeated. This system is designed to rigidly guarantee the objectives of forest ecological restoration while retaining the core value of restorative justice of encouraging responsibility and transformation through a flexible mechanism and to address capacity issues in actual implementation.