Thematic Evolution and Governance Structure of China’s Forest Resource Policy Planning: A Text Mining Analysis from a Multi-Level Governance Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction and Literature Review

1.1. Forest Governance in a Global Context: Challenges and China’s Position

1.2. Theoretical and Methodological Foundations

1.2.1. The Potential of Text Mining for Overcoming Traditional Analytical Limits

1.2.2. Multi-Level Governance (MLG) as a Global Lens for Environmental Policy

1.3. Research Gaps and Positioning of the Study

- (1)

- What have been the core themes of China’s forest resource policy planning since 1980, and how have their prominence and substance evolved over time?

- (2)

- How do these policy themes and priorities differ across key governance dimensions—the vertical administrative hierarchy (central to county), the horizontal array of departmental types, and the geospatial regions—revealing the division of labor and potential tensions within the system?

- (3)

- How do these empirical patterns reflect the distinctive characteristics of China’s state-led multi-level governance model, and what are the implications for understanding its operational logic in a comparative global context?

2. Research Design and Methodology

2.1. Data Source and Description

2.2. Analytical Framework and Methodology

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Overall Characteristics of China’s Forest Resource Policy Publications

3.2. Identification and Interpretation of China’s Forest Resource Policy Themes

3.3. Multi-Dimensional Distribution Characteristics of China’s Forest Resource Policy Themes

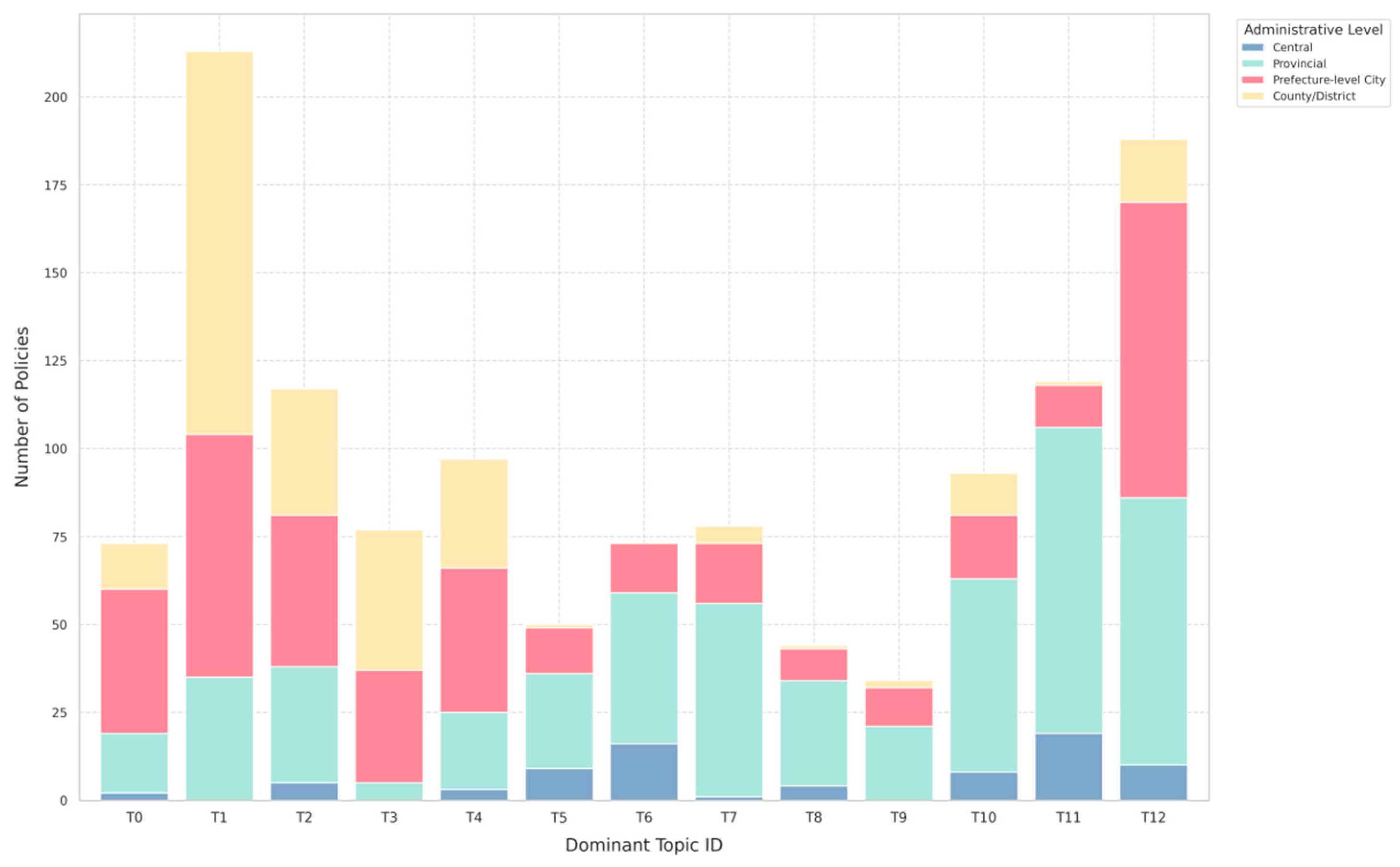

3.3.1. Distribution Characteristics of Themes by Administrative Level

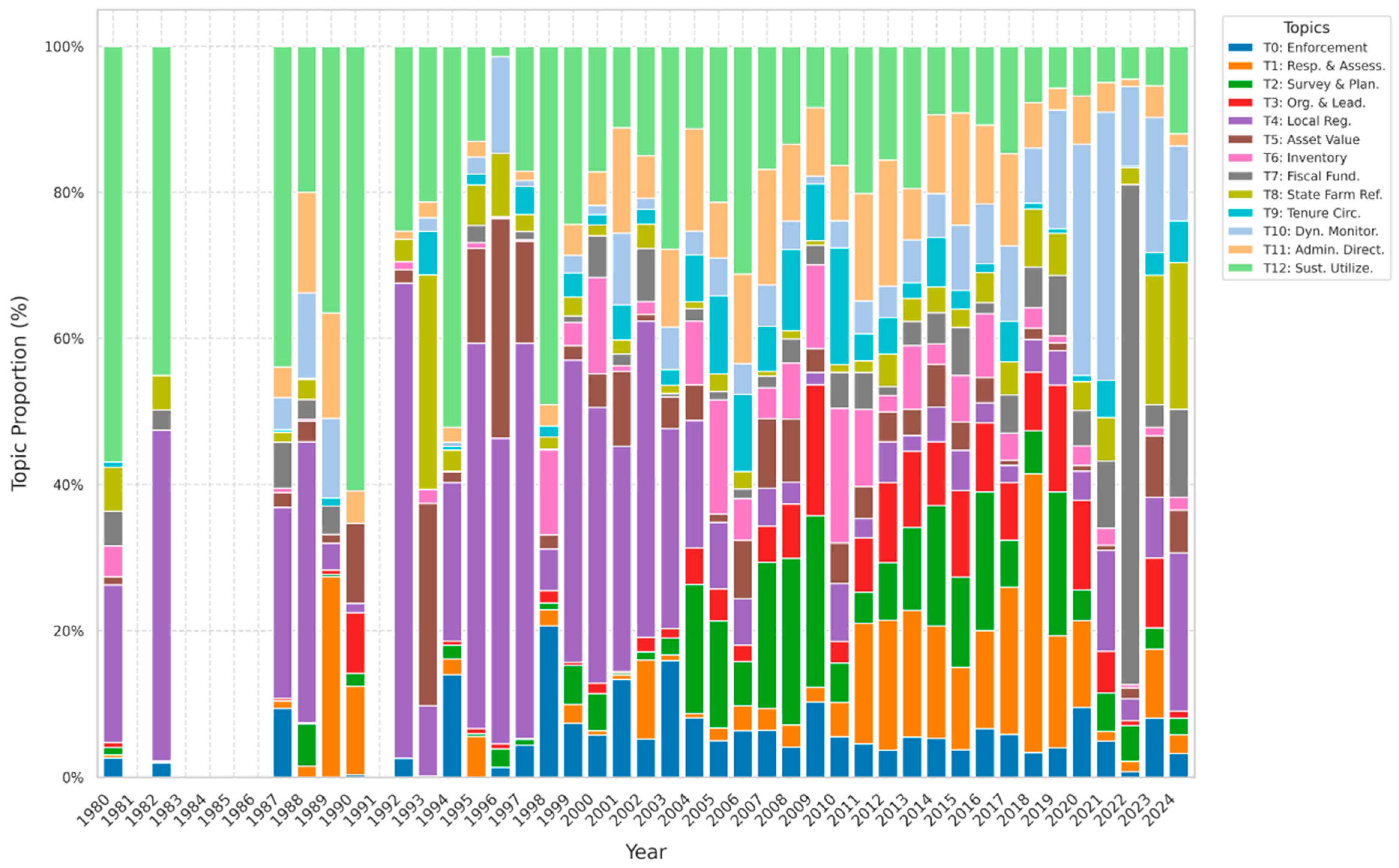

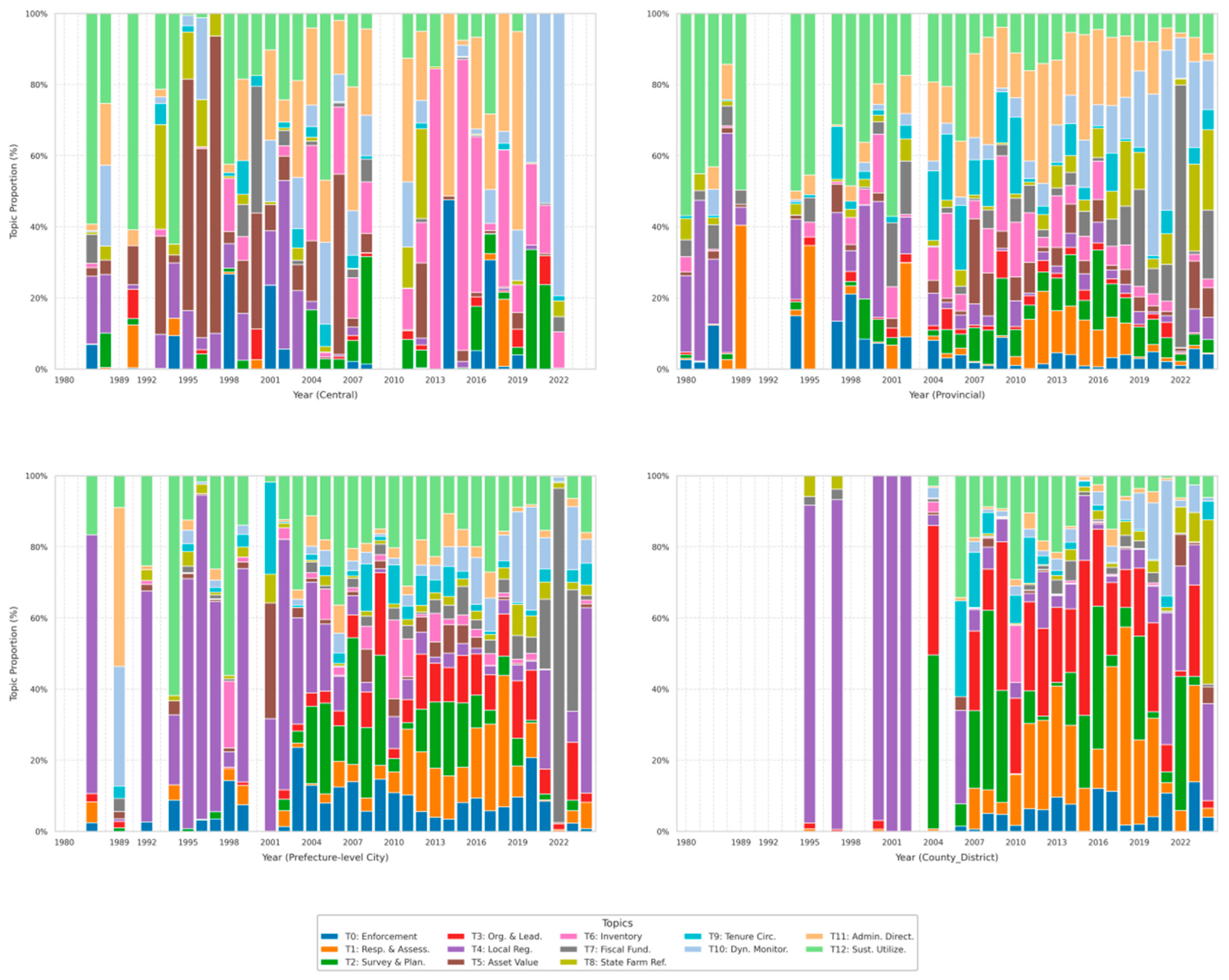

3.3.2. Overall and Level-Specific Temporal Evolution of Themes

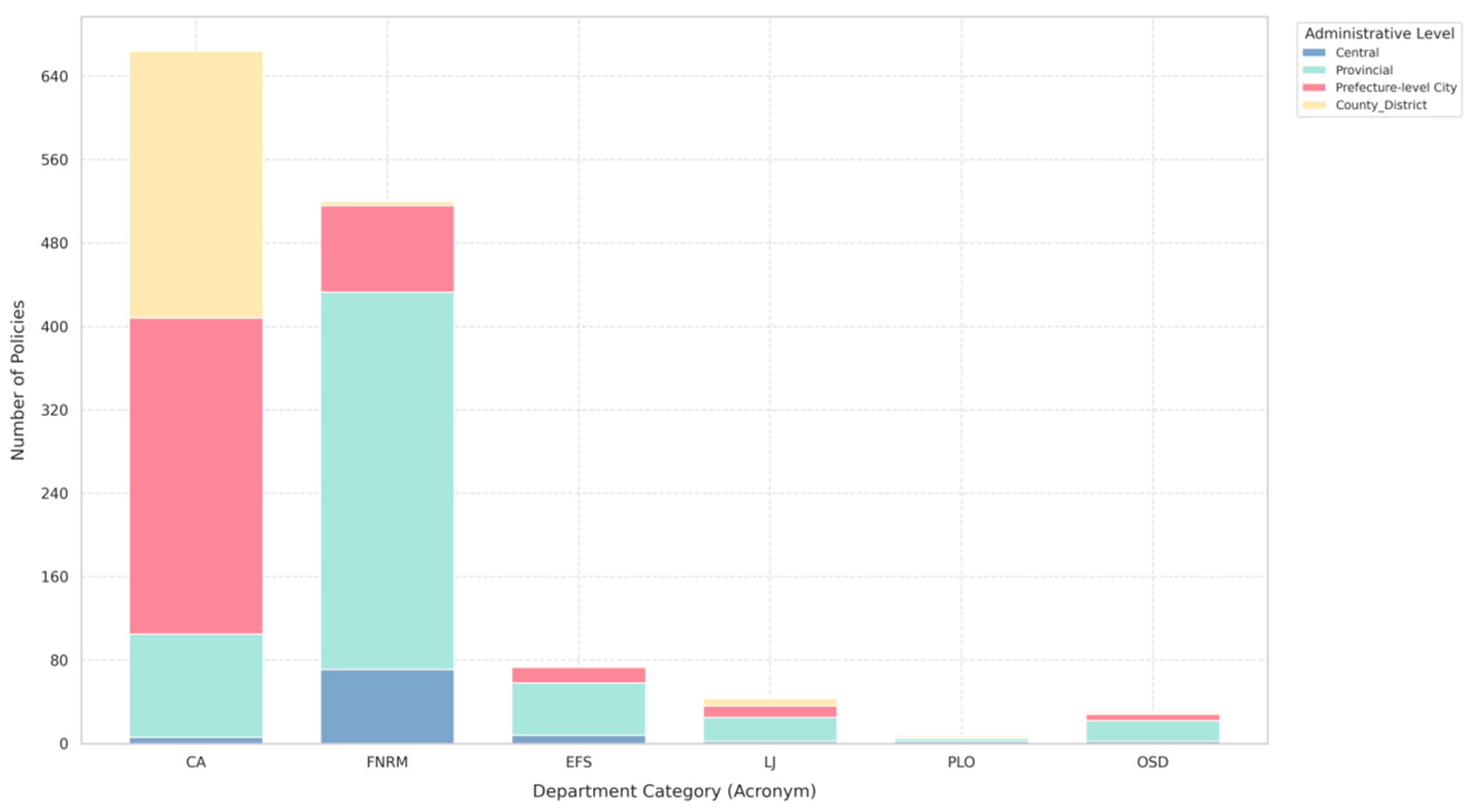

3.4. Distribution and Focus of Policy Themes Among Different Issuing Departments

3.4.1. Characteristics of Policy Publications by Department Type

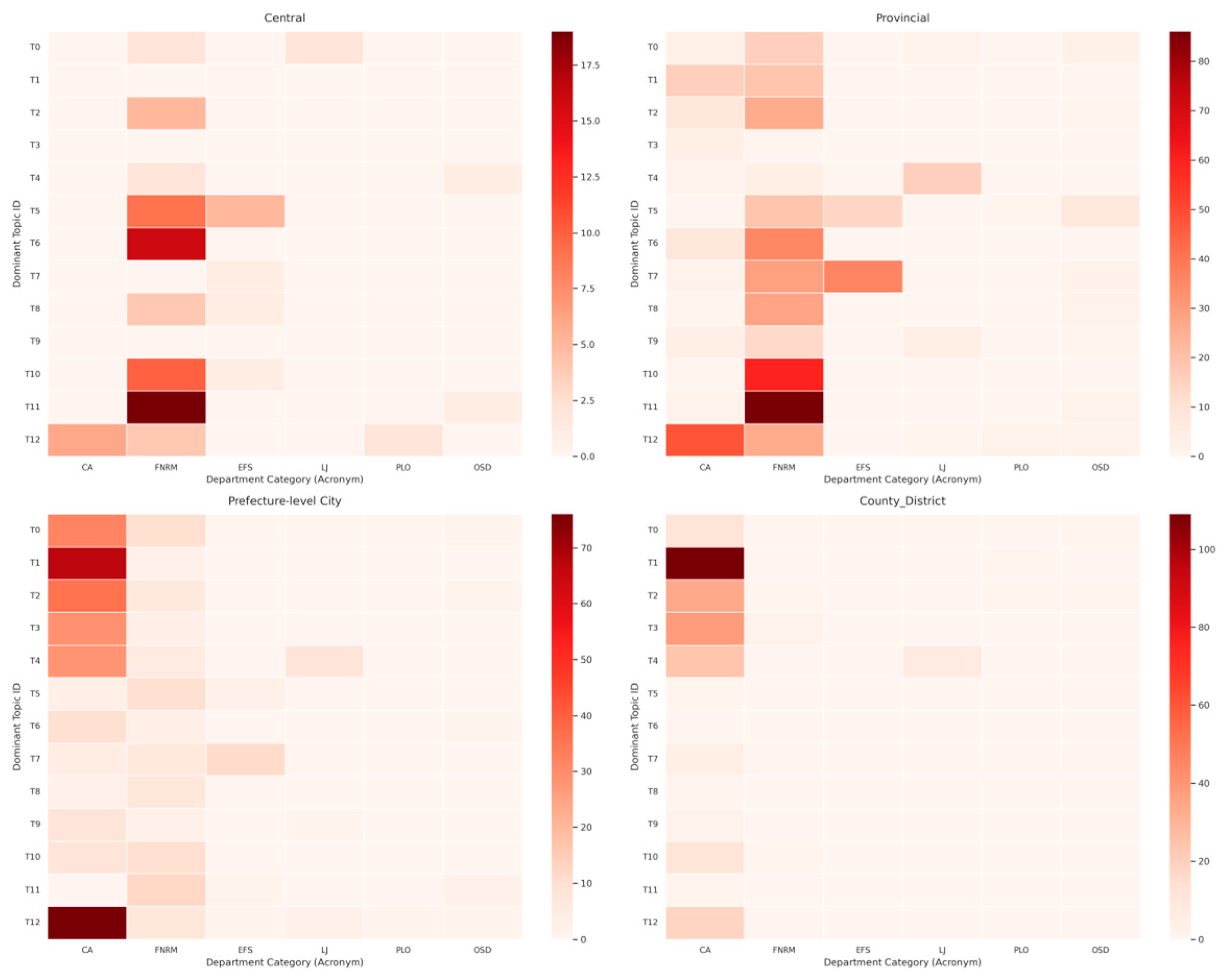

3.4.2. Cross-Analysis Heatmap of Issuing Departments and Policy Themes by Administrative Level

3.5. Distribution and Focus of Policy Themes Across Different Geographical Regions

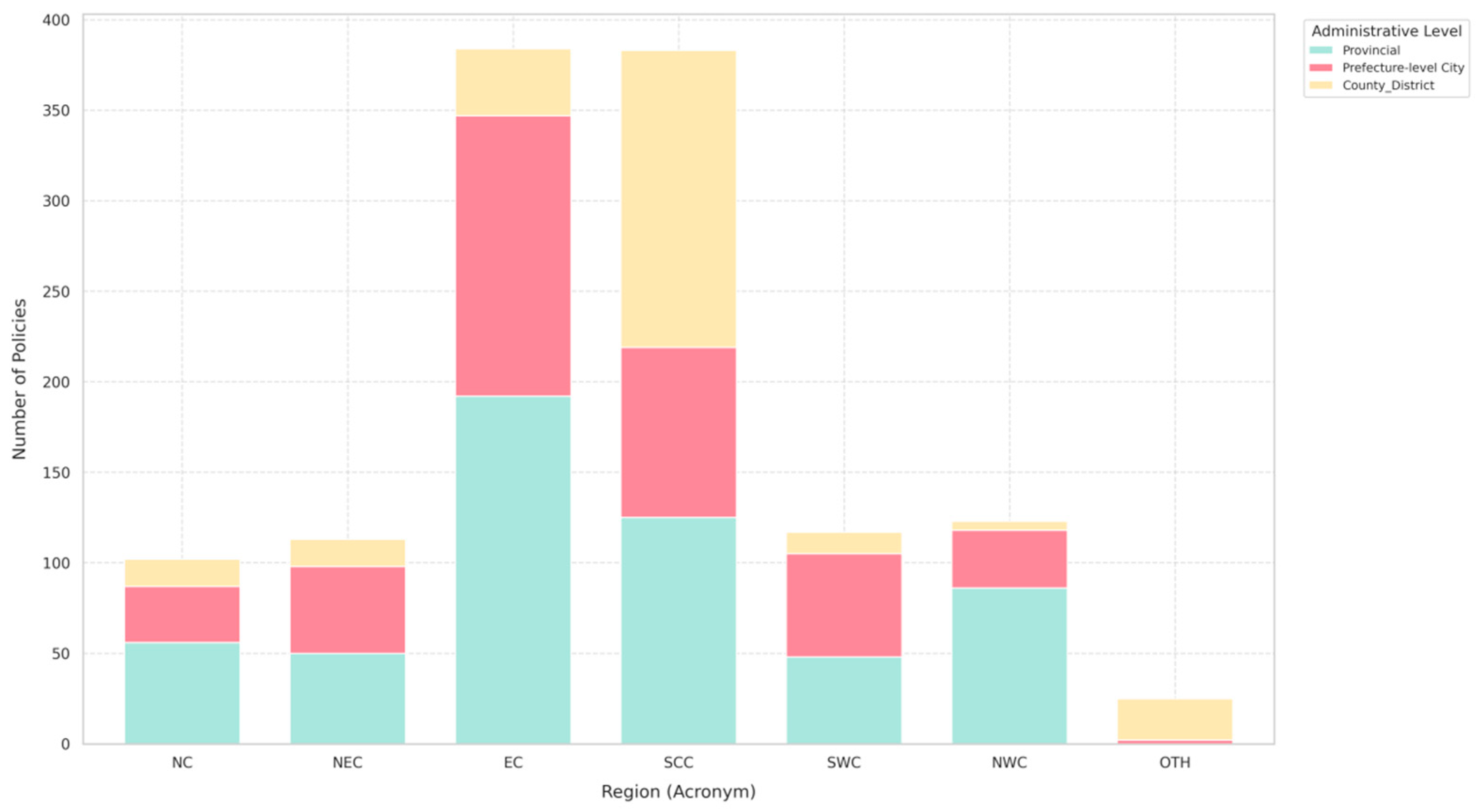

3.5.1. Characteristics of Policy Publications by Geographical Region (Excluding Central Level)

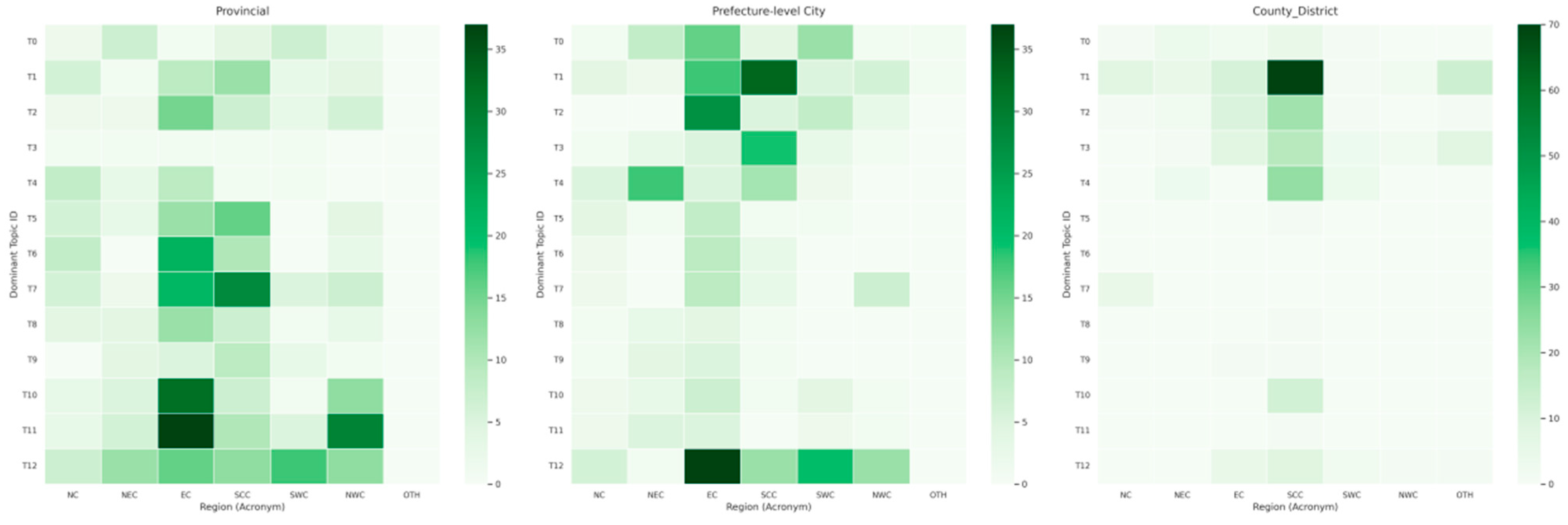

3.5.2. Cross-Analysis Heatmap of Geographical Regions and Policy Themes by Administrative Level (Excluding Central Level)

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis and Theoretical Dialogue on Key Research Findings

4.1.1. The Dynamic Evolution of Policy Themes: State-Led Agenda-Setting and Policy Learning

4.1.2. Hierarchical Differentiation: Vertical Policy Diffusion in a State-Led MLG Model

4.1.3. Departmental Division of Policy Themes: The Horizontal Dimension of MLG

4.1.4. The Spatial Patterns of Policy Themes: Adaptive Governance in Practice

4.2. Contributions, Implications, and Innovations

4.2.1. Theoretical and Methodological Contributions

4.2.2. Policy Implications

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Key Findings; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Special Report on Climate Change and Land. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Ometto, J.P.; Kalaba, F.K.; Anshari, G.Z.; Chacón, N.; Farrell, A.; Halim, S.A.; Neufeldt, H.; Sukumar, R. Cross-Chapter Paper 7: Tropical Forests. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 2369–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninan, K.N.; Inoue, M. Valuing forest ecosystem services: What we know and what we don’t. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 93, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, D.J. Economic Value of Forest Ecosystem Services: A Review; The Wilderness Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Available online: https://www.sierraforestlegacy.org/Resources/Conservation/FireForestEcology/ForestEconomics/EcosystemServices.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. Focusing on Building a Beautiful China and Deepening the Reform of the Ecological Civilization System. Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202411/content_6989076.htm (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Dai, L.; Zhao, W.; Shao, G.; Lewis, B.J.; Yu, D.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, W. The Progress and Challenges in Sustainable Forestry Development in China. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2013, 20, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, A.S.T.; Harrell, S. Paradoxes and Challenges for China’s Forests in the Reform Era. China Q. 2014, 218, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, W.; Ding, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Dai, L. Forest Management in Northeast China: History, Problems, and Challenges. Environ. Manag. 2011, 48, 1122–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, C.; Xiaomei, Z. Optimization of Regional Forestry Industrial Structure and Economic Benefit Based on Deviation Share and Multi-Level Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 37, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jactel, H.; Koricheva, J.; Castagneyrol, B. Responses of Forest Insect Pests to Climate Change: Not So Simple. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2019, 35, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. Forest Law of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://npcobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/2019-Forest-Law-Revision_Gazette.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Guiding Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Improving the Long-Term Mechanism for the Reform and Development of State-Owned Forest Farms and Forest Areas. Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-01/08/content_5467462.htm (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Yang, H. China’s Natural Forest Protection Program: Progress and Impacts. For. Chron. 2017, 93, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xian, J.; Xia, C.; Cao, S. Cost–Benefit Analysis for China’s Grain for Green Program. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 151, 105850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Wang, Y.; Su, D.; Zhou, L.; Yu, D.; Lewis, B.J.; Qi, L. Major Forest Types and the Evolution of Sustainable Forestry in China. Environ. Manag. 2011, 48, 1066–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Wan, S.; Zhou, Y.; Ke, S.; He, Y. Ecological Effects of Forest Tenure Reform in Southern China: An Institutional Change Perspective. Sustain. Dev. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.S.; Yang, Y.X.; Wu, J.; Shi, M.M. Ecological Compensation in China- Progress, Problems and Prospects. Adv. Mat. Res. 2013, 726–731, 988–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Peng, R.; Liao, W. Does Collective Forest Tenure Reform Improve Forest Carbon Sequestration Efficiency and Rural Household Income in China? Forests 2025, 16, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B. Challenges in Traditional Qualitative Analysis Approach Methods. Insight7. Available online: https://insight7.io/challenges-in-traditional-qualitative-analysis-approach-methods/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Ahmed, S.A.J.A.; Bapatdhar, N.; Kumar, B.P.; Ghosh, S.; Yachie, A.; Palaniappan, S.K. Large scale text mining for deriving useful insights: A case study focused on microbiome. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 933069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margetts, H.; Dorobantu, C. Computational Social Science for Public Policy. In Handbook of Computational Social Science for Policy; Bertoni, E., Fontana, M., Gabrielli, L., Signorelli, S., Vespe, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, E.; Fontana, M.; Gabrielli, L.; Signorelli, S.; Vespe, M. (Eds.) Handbook of Computational Social Science for Policy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Lee, J.; Machado, J.; Kim, G. Big-Data-Based Text Mining and Social Network Analysis of Landscape Response to Future Environmental Change. Land 2022, 11, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, G.B.; Kumar, R.P. A Comprehensive Survey on Topic Modeling in Text Summarization. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Communication, Computing and Electronics Systems; Sambath, R., Latha, R.L.R., Sangeetha, S.K.B., Hock, P.A.R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 373, pp. 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Liu, T.; Li, L.; Zhang, J. Non-Negative Matrix Factorization: A Survey. Comput. J. 2021, 64, 1080–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, S.; Choo, J.; Lee, J.; Reddy, C.K. Local Topic Discovery via Boosted Ensemble of Nonnegative Matrix Factorization. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Melbourne, Australia, 19–25 August 2017; pp. 4944–4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Castellanos, L.A.; Versini, P.-A.; Bonin, O.; Tchiguirinskaia, I. A Text-Mining Approach to Compare Impacts and Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kaushik, K.; Awasthy, P.; Gawande, A. Leveraging Text Mining for Trend Analysis and Comparison of Sustainability Reports: Evidence from Fortune 500 Companies. Am. Bus. Rev. 2022, 25, 416–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Du, H. Research on the Identification and Evolution of Health Industry Policy Instruments in China. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1264827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, I.; Duarte, L.; Teodoro, A.C. Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) in Fire Susceptibility. Proc. SPIE 2024, 13197, 1319719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ren, X.; Chen, S.; Xie, G.; Hu, Y.; Gao, D.; Tian, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, H. Deep Optimization of Water Quality Index and Positive Matrix Factorization Models for Water Quality Evaluation and Pollution Source Apportionment Using a Random Forest Model. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 347, 123771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Fu, D.; Xing, Y.; Duan, H.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F. A Scale for Evaluating the Willingness of National Forest Farm to Participate in Forest Carbon Sink Project. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 374, 124087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooghe, L.; Marks, G. A Postfunctionalist Theory of Multilevel Governance. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 2020, 22, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschhorn, F. A Multi-Level Governance Response to the Covid-19 Crisis in Public Transport. Transp. Policy 2021, 112, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreurs, M.A. Multi-level Governance and Global Climate Change in East Asia. Asian Econ. Policy Rev. 2010, 5, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piattoni, S. The Theory of Multi-Level Governance: Conceptual, Empirical, and Normative Challenges; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, Y.; Tortola, P.D.; Geyer, N. Taking Stock of the Multilevel Governance Research Programme: A Systematic Literature Review. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2024, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homsy, G.C.; Liu, Z.; Warner, M.E. Multilevel Governance: Framing the Integration of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Policymaking. Int. J. Public Adm. 2018, 42, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniell, K.A.; Kay, A. (Eds.) Multi-Level Governance: Conceptual Challenges and Case Studies from Australia; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Huang, C.; Chen, T.; Xu, X.; Liu, W. Multilevel Environmental Governance: Vertical and Horizontal Influences in Local Policy Networks. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prianto, A.L.; Abdillah; Yama, A. Multi-Level Governance as a Climate Change Adaptation Strategy in the Coastal Cities in Indonesia and Thailand. J. Gov. Polit. 2024, 6, 12–26. Available online: https://journal.ummat.ac.id/index.php/JSIP/index (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Di Gregorio, M.; Fatorelli, L.; Paavola, J.; Locatelli, B.; Pramova, E.; Nurrochmat, D.R.; May, P.H.; Brockhaus, M.; Sari, I.M.; Kusumadewi, S.D. Multi-level governance and power in climate change policy networks. Global Environ. Change 2019, 54, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Gao, H.; Chen, G.; Dai, X.; Xu, W.; Wang, Z. The Complexity of Environmental Policy Implementation in China: A Set-Theoretic Approach to Environmental Monitoring Policy Dynamics. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 11, 1335569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, S. Multi-Level Governance of Low-Carbon Tourism in Rural China: Policy Evolution, Implementation Pathways, and Socio-Ecological Impacts. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 12, 1482713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; He, A.J. Central–Local Relations, Accountability, and Defensive Administration: Unraveling the Puzzling Shrinkage of China’s Urban Social Safety Net. J. Soc. Policy 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandour, C.; Mourão, J. Fighting Deforestation in the Amazon: Strategic Coordination and Priorities for Federal and State Governments. Climate Policy Initiative. Available online: https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/fighting-deforestation-in-the-amazon-strategic-coordination-and-priorities-for-federal-and-state-governments/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Natural Resources Canada. Legality and Sustainability. Available online: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/forest-forestry/sustainable-forest-management/legality-sustainability (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Rooth, A. Fragmentation of Global Forest Governance and Its Consequences: The Case of the Collaborative Partnership on Forests. Master’s Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/384219 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Sotirov, M.; Pokorny, B.; Kleinschmit, D.; Kanowski, P. International Forest Governance and Policy: Institutional Architecture and Pathways of Influence in Global Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ke, X.; Shi, H. Topic Modeling and Evolutionary Trends of China’s Language Policy: A LDA-ARIMA Approach. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0324644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Explanation on the Institutional Reform Plan of the State Council. Chinese Government Website. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-03/14/content_5273856.htm (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Rawat, P.; Morris, J.C.; Knutsen, W.L.; Weiner, T.; David, C.-P.; Kingdon, J.W.; Dow, K. Kingdon’s “streams” model at thirty: Still relevant in the 21st century? Polit. Policy 2016, 44, 608–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovinskaya, T.L. Concept of “Ecological Civilization” as a Foundation of China’s “Green” Strategy. World Econ. Int. Relat. 2024, 68, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yan, G.; Ma, M.; Zhou, S.; Qian, Y. Spatio-temporal dynamics of China’s ecological civilization progress after implementing national conservation strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, I.; Chakwizira, J. Advancing a performance management tool for service delivery in local government. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adham, K.A.; Sarkam, S.F.; Said, M.F.; Nasir, N.M.; Kasimin, H. Monitoring of policy implementation: Convergent mobile and fixed technologies as emergent enablers. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2017, 30, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, J. The impact of vertical and horizontal pressures on policy diffusion: Evidence from APLS adoption in China. J. Chin. Gov. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China. Duties and Functions of the Ministry of Finance. Available online: http://www.mof.gov.cn/en/abus/mf/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Provisions on the Functions, Internal Institutions and Staffing of the National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Chinese Government Website. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2018-09/11/content_5320993.htm (accessed on 7 May 2025).

| Category | Explanation and Main Functions | Examples of Representative Departments |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Administrative Departments | Refers to people’s governments, administrative offices, and management committees at all levels. As the highest administrative organs in their respective jurisdictions, they are responsible for the overall leadership and comprehensive coordination of all affairs, as well as the final decision-making, approval, and promulgation of major policies (including in the forestry sector). In forestry affairs, their role is more focused on providing macro-level guidance, setting development directions, and conducting comprehensive, cross-departmental management. | “People’s Government”, “Administrative Office”, “Management Committee”, etc., at various levels. |

| Forestry and Natural Resource Management Departments | Refers to forestry (and grassland) authorities, landscaping and greening departments at all levels, as well as the natural resource departments that integrated forestry responsibilities after institutional reforms. These are the core government functional bodies specifically responsible for the planning, conservation, cultivation, utilization, monitoring, and the management of natural ecosystems such as forests, grasslands, wetlands, and deserts, as well as wildlife resources within their jurisdictions. They are the primary entities for the research, formulation, and implementation of specialized policies and technical regulations concerning forestry industry development, ecological construction, resource conservation, and disaster prevention. | “Forestry Bureau/Department”, “Forestry and Grassland Bureau/Department”, “Landscaping and Greening Bureau”, “XX Forestry (and Landscaping/and Grassland) Administration”, “Ecological Construction Administration” (if forestry is a primary function), “Natural Resources Department/Bureau” (if explicitly including forestry management functions), “Office of the Forest Chief”, etc., at various levels. |

| Economic Planning and Fiscal-Financial Support Departments | Includes “Development and Reform Departments” responsible for national economic and social development planning and the approval of major projects; “Finance Departments” responsible for fiscal budgets, fund allocation and management, and formulating fiscal and tax incentive policies; and other economic regulation departments involved in forestry-related economic activities such as financial support, market trade, and price management (e.g., the former “Price Bureau”, certain functions of “Commerce Departments”, and local “Financial Regulatory Departments” concerning policies like green finance). Together, they provide economic strategy guidance, financial guarantees, and market environment support for forestry development. | “Ministry/Department/Bureau of Finance”, “Development and Reform Commission”, “Customs” (when involving import/export tax policies for forest products), “Price Bureau”, etc., at various levels. |

| Legislative and Judicial Support Departments | Includes “People’s Congresses and their Standing Committees”, “People’s Courts”, and “People’s Procuratorates” at all levels. As state power organs, the People’s Congresses and their Standing Committees are responsible for formulating and promulgating local regulations concerning forest resource protection and forestry development, and for supervising related government work. The judicial and procuratorial organs, through methods such as hearing forestry-related cases, issuing judicial interpretations, and conducting procuratorial supervision, ensure the correct implementation of forestry laws and regulations and safeguard order in forest areas as well as the legitimate rights and interests of the state, collectives, and citizens. | “People’s Congress (including its Standing Committee)”, “People’s Court”, “People’s Procuratorate”, at various levels. |

| Party Leadership Organs | Refers to the committees of the Communist Party of China (CPC) at all levels (Party Committees) and their relevant working departments (e.g., the General Office of the Party Committee, Policy Research Office). In China, where the Party exercises overall leadership, the Party Committees play a leading and decision-making role in major principles and policies, strategic directions, and key personnel appointments concerning socio-economic development, including forestry. Documents such as opinions and decisions issued by them carry significant policy guidance weight. | “CPC XX Committee”, “Office of the CPC XX Committee”, etc. |

| Other Specialized Collaborative Departments | Refers to government functional departments, other than those in the main categories above, that collaboratively participate in the formulation, implementation, or supervision of forestry-related policies from their specific professional domains. For example, Agriculture and Rural Affairs Departments (may involve under-forest economy, rural collective forest tenure reform), Market Supervision and Administration Departments (forest product quality and safety), Transportation Departments (forest area roads), Audit Departments (auditing forestry funds), and Ecological Environment Departments (environmental impact assessments, protected area management). These departments influence forestry policy or provide professional support within their specific scopes of responsibility. | “Agriculture and Rural Affairs Bureau/Committee/Department”, “Market Supervision and Administration Bureau”, “Transportation Department/Bureau”, “Audit Department/Bureau”, “Commerce Department/Bureau” (for trade rules), “Civil Affairs Department” (for land names/historical tenure), “Public Security Organs” (for forest area security). |

| Region Name | Provinces Included | Regional Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| North China | Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei Province, Shanxi Province, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region | Located in the temperate continental monsoon climate zone with a relatively low forest coverage rate, dominated by temperate deciduous broad-leaved forests. The Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region faces significant ecological pressure, with an urgent need for shelterbelt systems. Shanxi, rich in coal, has major ecological restoration tasks in mining areas. Inner Mongolia has interlaced grasslands and forests, emphasizing both desertification control and the protection of grasslands and forests. Area: approx. 1.56 million km2; Population density: 105 people/km2. |

| Northeast China | Liaoning Province, Jilin Province, Heilongjiang Province | China’s most important natural forest region, rich in forest resources, dominated by cold-temperate coniferous forests and temperate coniferous-broadleaf mixed forests. The Greater/Lesser Khingan and Changbai Mountains are national key forest areas, once ranking first in timber production. Following the implementation of the Natural Forest Protection Program, the focus has shifted from timber production to ecological conservation. Area: approx. 0.79 million km2; Population density: 138 people/km2. |

| East China | Shanghai, Jiangsu Province, Zhejiang Province, Anhui Province, Fujian Province, Jiangxi Province, Shandong Province, Taiwan Province | An economically developed and densely populated region with a high forest coverage rate but low per capita forest area. Dominated by subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forests; provinces like Zhejiang, Fujian, and Jiangxi are relatively rich in forest resources. There is high demand for urban forests and forest parks, and forestry is highly industrialized, with well-developed bamboo, flower, and nursery stock industries. Area: approx. 0.80 million km2; Population density: 483 people/km2. |

| South Central China | Henan Province, Hubei Province, Hunan Province, Guangdong Province, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Hainan Province, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR | A region with a large north–south span and diverse climates, transitioning from temperate to tropical. The middle reaches of the Yangtze River are rich in wetlands. Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan have abundant tropical/subtropical forests and are key bases for fast-growing, high-yield plantations. The Pearl River Delta urban agglomeration has a high demand for greening. Great potential for forest tourism and under-forest economy. Area: approx. 1.01 million km2; Population density: 378 people/km2. |

| Southwest China | Chongqing, Sichuan Province, Guizhou Province, Yunnan Province, Tibet Autonomous Region | Characterized by complex topography, distinct vertical zonation, and extremely rich biodiversity. The Hengduan Mountains and the eastern edge of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau are global biodiversity hotspots. Sichuan and Yunnan form a critical ecological barrier for the upper Yangtze River. The Tibetan Plateau’s ecosystem is fragile. Faces significant tasks in natural forest protection, the “Grain for Green” program, and biodiversity conservation. Area: approx. 2.37 million km2; Population density: 82 people/km2. |

| Northwest China | Shaanxi Province, Gansu Province, Qinghai Province, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region | An arid and semi-arid region with low forest coverage and a fragile ecological environment. Dominated by desert vegetation and grasslands, with forests mainly in mountainous areas. It is a key area for the “Three-North Shelterbelt System”, facing arduous tasks in desertification control and soil/water conservation. The Tianshan and Altai Mountains in Xinjiang possess important mountain forest resources. Area: approx. 3.11 million km2; Population density: 32 people/km2. |

| Topic_ID | Top_Words | Assigned_Doc_Count | Topic Name | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic_0 | special campaign, destruction, illegal crimes, cases, crackdown | 73 | Forest Resource Law Enforcement and Crackdown on Illegal Activities | The core keywords for this topic, such as “special campaign”, “illegal crimes”, “crackdown”, “investigate and handle”, and “Public Security Bureau”, along with specific illegal acts like “deforestation”, clearly point to law enforcement actions and special rectification campaigns. These are targeted at various criminal activities that destroy forest resources and forestland. This theme reflects the policy’s emphasis on maintaining order in the forestry sector and punishing illegal behavior. |

| Topic_1 | assessment, target responsibility system, protection, development, people’s government | 213 | Target Responsibility and Assessment for Forest Resource Protection and Development | Distinctive keywords such as “assessment”, “target responsibility system”, “target”, “assessment measures”, “indicator”, and “score” characterize this topic. They indicate that these policies focus on establishing and implementing a target-oriented responsibility system and evaluating the performance of various government levels (particularly “People’s Governments”, “sub-districts”, and “townships”) in the “protection” and “development” of forest resources through formal assessments and inspections. |

| Topic_2 | Survey, Type II survey, work, planning and design, sub-compartment | 117 | Forest Resource Survey, Planning, and Data Management | Keywords such as “survey” (particularly “Type II survey” and “field survey”), “planning and design”, “sub-compartment” (the smallest unit in forest inventory and planning), “results”, and “data” are central to this theme. They collectively refer to the foundational work of forest resource inventory, monitoring, data collection, results management, and associated planning and design efforts. This reflects the policy’s emphasis on the importance of scientifically understanding the state of forest resources. |

| Topic_3 | leading group, office, deputy director, director, people’s government | 77 | Organizational Structure and Leadership Coordination in Forestry Management | The keywords of this topic primarily revolve around institutional names like “leading group”, “office”, “People’s Government”, and “Forestry Bureau”, along with job titles such as “director”, “deputy director”, and “member”, and organizational actions like “establish” and “work”. This indicates that the related policies focus on the organizational leadership, institutional setup, and personnel arrangements for forestry management work. |

| Topic_4 | autonomous county, forest trees, competent authority, felling, regulations | 97 | Local Forestry Administrative Regulations and Felling Permit Management | Keywords such as “autonomous county”, “regulations”, “administrative”, “competent authority”, “felling”, “permit”, and “fine” collectively describe administrative regulations and permit systems at the local level (especially in autonomous counties) for activities like tree felling and timber operations. This reflects specific policy provisions for regulating tree felling and managing resources according to law. |

| Topic_5 | asset valuation, asset, mortgage, valuation, approval | 50 | Forest Resource Asset Valuation and Mortgage Financing | Keywords in this theme, including “asset valuation”, “mortgage”, “loan”, “mortgage registration”, and “valuation agency”, clearly point to financial activities involving the valuation of forest resources as assets and their use for obtaining loans via mortgages. This reflects a policy orientation toward exploring the capitalization and market-based operation of forest resources. |

| Topic_6 | inventory work, inventory, eighth, continuous inventory, national | 73 | National/Regional Forest Resource Inventory and Sample Plot Monitoring | Keywords such as “inventory work”, “continuous inventory”, “national”, “provincial-wide”, “sample plot”, and references to the “eighth” and “ninth” (typically referring to the rounds of the National Continuous Forest Inventory) indicate that these policies focus on large-scale, systematic forest resource inventories and sample-plot-based monitoring conducted at the national or provincial level. |

| Topic_7 | funds, budget, allocate, resource tending, expenditure | 78 | Forestry Fiscal Funding Input and Performance Management | Keywords like “funds”, “budget”, “Department of Finance”, “special funds”, “central finance”, “expenditure”, and “performance” are directly linked to the financial sources, budgetary arrangements, allocation and use of funds, and the performance management of fiscal capital for forestry development. This reflects policy content aimed at guaranteeing forestry investment and enhancing the effectiveness of funds. |

| Topic_8 | state-owned, forest farm, paid use, asset, audit | 44 | Reform of State-Owned Forest Farms and Paid Use of Assets | Core keywords such as “state-owned forest farm”, “reform of state-owned forest farms”, “paid use”, “asset”, “audit”, and “director’s departure audit” clearly indicate that these policies concern the institutional reform, asset management, and transformation of operational models (e.g., promoting paid use) of state-owned forest farms, as well as related auditing and supervision. |

| Topic_9 | circulation, resource circulation, forest, contract, forest tenure | 34 | Forest Tenure Circulation and Contract Management | Terms like “circulation”, “forest tenure”, “ownership”, “contracting”, “transfer”, “contract”, and “forestland use rights” are central to this theme. They reflect policy regulations concerning the circulation (e.g., contracting, transfer) of ownership and usage rights of forests, trees, and forestland among different entities, as well as the associated contract signing and management. |

| Topic_10 | forest, supervision, one map, update, resource management | 93 | Dynamic Monitoring of Forest Resources and “One Map” Management | Keywords like “supervision”, “monitoring”, “one map” (a common concept in forestry resource management), “map patch”, “update”, “change”, and “database” describe the policy direction of using modern information technology. These policies focus on the dynamic monitoring of resources like forests and grasslands, data updates, and change verification, promoting visual and fine-grained management through integrated systems such as the “One Map” approach. |

| Topic_11 | State Forestry Administration, Forestry Bureau, resource management, inspection, provincial forestry department | 119 | Administrative Directives and Work Deployment by Forestry Authorities | High-frequency words in this theme include various levels of forestry authorities, such as the “State Forestry Administration” and “Provincial Forestry Department”, as well as administrative actions like “inspection”, “supervision”, “training”, “meeting”, and “forwarding”. This suggests that these policies primarily concern administrative management activities, such as higher-level forestry authorities deploying work, conveying instructions, conducting supervision, and organizing training for lower levels. |

| Topic_12 | protection, forest, forestry, felling, construction | 188 | Comprehensive Protection and Sustainable Utilization of Forest Resources | This is a relatively comprehensive theme, encompassing core aspects of forestry work such as “protection”, “development”, “management”, “construction”, “felling” (including “felling quotas”), and “ecology”. Together, these keywords point toward a macro-policy direction and the building of an institutional framework aimed at the comprehensive protection, scientific management, rational utilization, and sustainable development of forest resources. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, H.; Yin, Y.; Wang, C.; Cai, J.; Xie, Y. Thematic Evolution and Governance Structure of China’s Forest Resource Policy Planning: A Text Mining Analysis from a Multi-Level Governance Perspective. Forests 2025, 16, 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16071185

Hu H, Yin Y, Wang C, Cai J, Xie Y. Thematic Evolution and Governance Structure of China’s Forest Resource Policy Planning: A Text Mining Analysis from a Multi-Level Governance Perspective. Forests. 2025; 16(7):1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16071185

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Haoqian, Yifen Yin, Chunning Wang, Jingwen Cai, and Yingchong Xie. 2025. "Thematic Evolution and Governance Structure of China’s Forest Resource Policy Planning: A Text Mining Analysis from a Multi-Level Governance Perspective" Forests 16, no. 7: 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16071185

APA StyleHu, H., Yin, Y., Wang, C., Cai, J., & Xie, Y. (2025). Thematic Evolution and Governance Structure of China’s Forest Resource Policy Planning: A Text Mining Analysis from a Multi-Level Governance Perspective. Forests, 16(7), 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16071185