3.1. Theoretical Analysis

In March 2013, the Chinese government launched a commitment to reduce at least one-third of administrative approval items across all departments of the State Council within five years, marking the beginning of the “Streamline Administration and Delegate Power” (RSDO) reform. This initiative aimed to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of governance while fostering market-driven economic activities. As part of this broader effort, the Chinese government later introduced the “Improve Regulation” and “Optimize Services” reforms in 2015, which together form a comprehensive institutional framework. The core of the “Streamline Administration and Delegate Power” initiative lies in reducing administrative approvals and transferring non-essential government functions to the market, thereby alleviating constraints on businesses and allowing the market to take a more decisive role in resource allocation. This approach, consistent with “Institutional Economics Theory”, aims to reduce transaction costs and increase economic efficiency, ultimately stimulating the vitality of market entities and fostering innovation. The “Improve Regulation” reform focuses on enhancing regulatory oversight during and after the business process, shifting from a model of “strict entry and loose regulation” to “loose entry and strict regulation”. This shift seeks to foster fair competition, mitigate market distortions, and ensure that deregulation does not lead to chaotic market behavior. This aspect of the reform aligns with “Dynamic Capabilities Theory”, which emphasizes how institutional improvements can strengthen firms’ capacities to innovate, adapt, and effectively compete in a newly liberated market environment. The “Optimize Services” component is designed to improve government service delivery by streamlining procedures, increasing service awareness, and introducing innovative methods of interaction with businesses. By ensuring that public services remain efficient and accessible even as administrative powers are reduced, this reform aims to avoid a “service vacuum” and ensure continued support for enterprise activities. This service optimization directly supports businesses’ ability to engage in more agile market behavior and expansion, which is consistent with “New Trade Theory”. The theory highlights how reducing operational costs and improving market access through enhanced governmental services can enable firms to diversify their products and markets, positioning them more effectively in global trade.

Together, these reforms aim to create a more business-friendly environment by reducing institutional and operational barriers, allowing firms to leverage market forces more effectively. By lowering administrative burdens, strengthening regulatory frameworks, and improving service delivery, the RSDO reforms enhance the overall competitiveness of enterprises, fostering export diversification and contributing to broader economic growth. This integrated approach not only aligns with theoretical frameworks but also provides a realistic and actionable pathway for promoting sustainable economic development in China.

3.1.1. Analysis of the Direct Impact of the RSDO

The RSDO covers a wide range. Thus, almost all departments potentially serve as reform implementers. In policy recommendations for promoting export diversification, governments should place greater emphasis on improving product quality and fostering innovation. The success of RSDO reforms lies not only in the growth in the number of products but also in innovation-driven export diversification. Governments should further streamline administrative processes, enhance intellectual property protection, and reduce innovation costs to provide stronger support for enterprise innovation. Particularly for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), governments can help reduce barriers to entering new markets, assisting them in improving product innovation and competitiveness, thereby driving higher-quality export diversification, for example, reducing and simplifying export-related approvals, improving customs clearance efficiency, providing international market information, and promoting overseas markets through streamlining administration and optimizing services. This can greatly reduce the difficulty for wood-processing enterprises to start an export business for the first time and the difficulty of entering new markets. This may directly promote wood-processing enterprises entering export markets and developing new markets, thus achieving higher export market diversification and expansion levels. Improvements in regulatory quality, judicial efficiency, intellectual property protection, and market dispute resolution have reduced the space for counterfeit and substandard products while increasing the cost of violations. WPEs are stimulated to place more emphasis and invest more resources in improving product quality and developing new products. This could promote an increase in the number of wood-processing enterprises exporting products. In summary, hypothesis H1 is proposed:

H1: Local RSDO has a direct positive effect on wood-processing enterprises’ export diversification.

3.1.2. Analysis of the Impact Mechanism of the RSDO

(1) Reducing operating costs. When analyzing export diversification, although the number of export products is a fundamental measure, we must also consider product quality and innovation. Product quality and innovation are critical drivers of export diversification, as they not only determine a product’s competitiveness in international markets but also directly impact whether enterprises can enter new markets and maintain their market share. To achieve long-term export diversification, enterprises must continuously focus on improving product quality and fostering innovation, developing unique and high-value-added products. Through innovation, enterprises can not only increase the variety of export products but also enhance market share and enter higher-end markets. Classical and new trade theories suggest that country A enterprises with lower export prices for a particular product can enter the export market and trade with other countries. Additionally, if a new country demands the product internationally and its domestic price is higher than imports from country A, enterprises in country A can enter new export markets. Low prices stem from low costs, which are driven by higher production efficiency (due to technology level) or more abundant and cheaper factor endowments [

30]. This study’s average cost-to-income ratio (operating costs and period expenses to sales revenue) of 2141 WPEs is 84.01%. Even for enterprises below the 25th percentile, the average exceeds 80%, highlighting the need to help wood-processing enterprises reduce operating costs. Regional RSDO may help WPEs establish cost advantages through various channels, thereby enhancing the level of export product and market diversification for enterprises. The ‘Streamline Administration and Delegate Power’ reform covers all operational processes, including business establishment, material procurement, production, domestic sales, export, and transportation. For example, in February 2013, the Second Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee proposed reforms to the business registration system. Reforms such as the ‘subscribed capital registration system’ and the ‘cancellation of annual business inspections’ were later implemented. The establishment of the “power list” and “negative list” systems ensures that “what is not authorized by law cannot be done” and “what is not prohibited by law can be done” [

31]. Administrative service fees and government funds are managed through a catalog list system, canceling, suspending, and reducing over 1100 central and provincial government administrative service fees (including those in the import and export processes), resulting in a total reduction in market entities’ burdens by over CNY 3 trillion [

32]. The mentioned reforms help enterprises reduce institutional costs [

33], improve production and operating efficiency, and accelerate the production and supply of new products. The above improvements can offset the fixed and variable costs of export enterprises entering new export markets and reduce the sunk costs incurred after the failure to develop new markets. This may encourage enterprises to attempt to open new export markets. Additionally, these reforms may help enterprises open new export markets and increase product variety in existing markets, based on price advantages and product uniqueness [

34]. Thus, hypothesis H2 is proposed:

H2: The RSDO can enhance the export diversification level of enterprises by reducing operating costs.

(2) Promoting technological innovation. RSDO reforms, by simplifying administrative processes and lowering market entry barriers, have reduced operational costs for enterprises, creating favorable conditions for innovation and product quality improvement. Enterprises can allocate the cost savings to research and development and technological innovation, thereby enhancing product quality and competitiveness. This not only helps enterprises expand product variety in existing markets but also promotes their entry into new international markets. By providing a more equitable and competitive market environment, RSDO reforms encourage enterprises to drive export product diversification through innovation. Posner [

35] proposed the technology gap theory, which argues that the technology gap is one of the sources of comparative advantage and export benefits in international trade. Helpman and Krugman [

36] argued that innovation and supplying differentiated products are the basic conditions for enterprises to establish market power, expand sales scale, and obtain increasing returns to scale. The “trade driven by institutions” theory suggests that improvements in institutional quality can promote trade through at least three pathways: promoting technological innovation, human capital development and accumulation, and increasing returns to scale. Chinese wood-processing enterprises undergo a “cost curse” (i.e., costs rise uncontrollably after falling to an optimal point) as their cost advantage diminishes. They must accumulate technology to develop innovative products, achieving ‘what others don’t have, I possess’. Alternatively, they can produce differentiated products at the same cost, improve products to achieve ‘what others have, I excel at’, or offer superior products more cheaply. The RSDO can create a favorable external environment for technological innovation and quality improvement. First, the RSDO significantly lowers market entry barriers, entry time, and costs for new enterprises. This encourages more competitors in an industry, fostering market competition and stimulating enterprises to develop new products or explore new markets for survival and growth [

37]. Second, the RSDO provides a fair and competitive market environment, compressing the space for homogeneous or imitation products, which encourages the development of diversified products [

38]. Forcing enterprises to meet market demand by expanding the production of differentiated products enhances the expansion of export markets and increases the variety of export products for enterprises. Third, the RSDO ensures enterprises’ safety, stability, legality, fairness, freedom, convenience, and confidence, promoting the free flow of capital, technology, markets, and talent. This will enable enterprises to focus on long-term development to unlock existing capabilities and accumulate new ones, increase substantial innovations, and then build a foundation for productivity improvements and product diversification through technological diversification. In summary, hypothesis H3 is proposed:

H3: The RSDO can enhance the export diversification level of enterprises by promoting technological innovation. The mechanism of the impact of the RSDO on the export diversification of wood-processing enterprises is shown in Figure 1. 3.2. Research Methodology

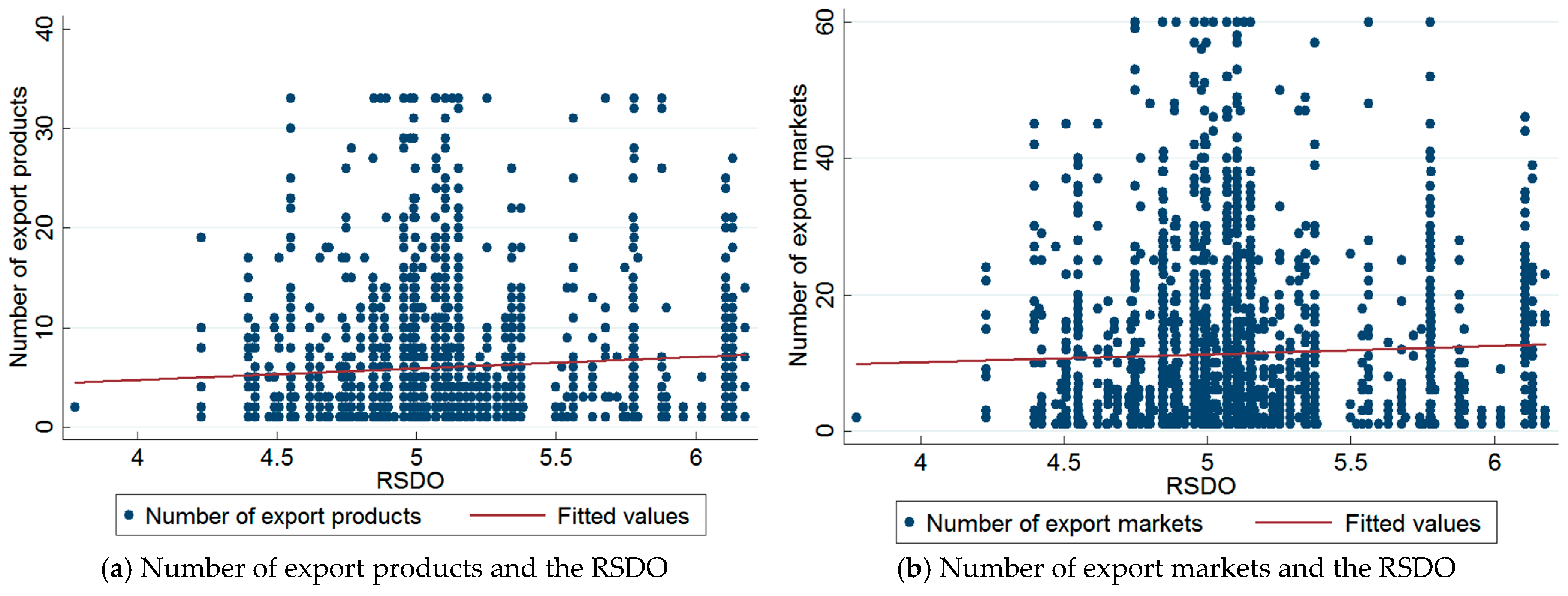

(1) Zero-truncated negative binomial regression. The number of WPE export products and markets is used as measurement variables for export diversification. Both are typical non-negative discrete variables suitable for count models, such as Poisson regression, negative binomial model, zero-truncated Poisson model, and zero-truncated negative binomial regression. Among them, the Poisson regression model has an important assumption: the conditional mean of the dependent variable is equal to its conditional variance. In this study, the number of export products and export markets of 2141 sample enterprises varies greatly. Their variances (116.46, 159.27) are much larger than the means (6.32, 11.55), making Poisson regression unsuitable. The negative binomial model does not require the expected value of the variable to equal the variance, which solves the problem present in Poisson regression [

39]. Moreover, export product data types and market quantities are “non-negative truncated integer data (zero-truncated data)”. The likelihood function must be adjusted for consistent estimation, whether it is the Poisson or negative binomial model [

40]. In summary, the zero-truncated negative binomial regression is introduced to identify the effects of the RSDO on the number of export products and export markets of WPEs. The initial Poisson regression model is designed:

In the equation,

yi is the dependent variable, representing the number of export products or export markets for the

i-th wood-processing enterprise. Since the condition of “the mean equals the variance for the number of export products and the number of export markets” is not met, the Poisson model is transformed into a negative binomial distribution model. At this point, an unobserved effect, denoted as

, is introduced into the conditional mean, which can affect the number of export products and markets for the sample enterprises. At this point, an unobserved effect, denoted as

a, is introduced into the conditional mean, which can affect the number of export products and markets for the sample enterprises. The Poisson model is extended to:

Taking the natural logarithm of both sides of Equation (2) results in the negative binomial distribution model:

In Equation (3), xi is the vector of control variables for the i-th enterprise, and is the vector of estimated coefficients for the control variables; η represents the effect of the RSDO on the number of export products or export markets, controlling for other explanatory variables; α is the constant term; εi is the random error term. The model estimation results based on zero-truncated negative binomial regression will produce an overdispersion parameter alpha; if the model rejects the null hypothesis of alpha = 0, it indicates that the negative binomial distribution model is superior to the Poisson regression model. Conversely, the opposite is true. The model estimation results will also generate the log-likelihood statistic and its p-value. If the p-value is less than 0.05, the zero-truncated negative binomial regression is superior to the standard negative binomial regression.

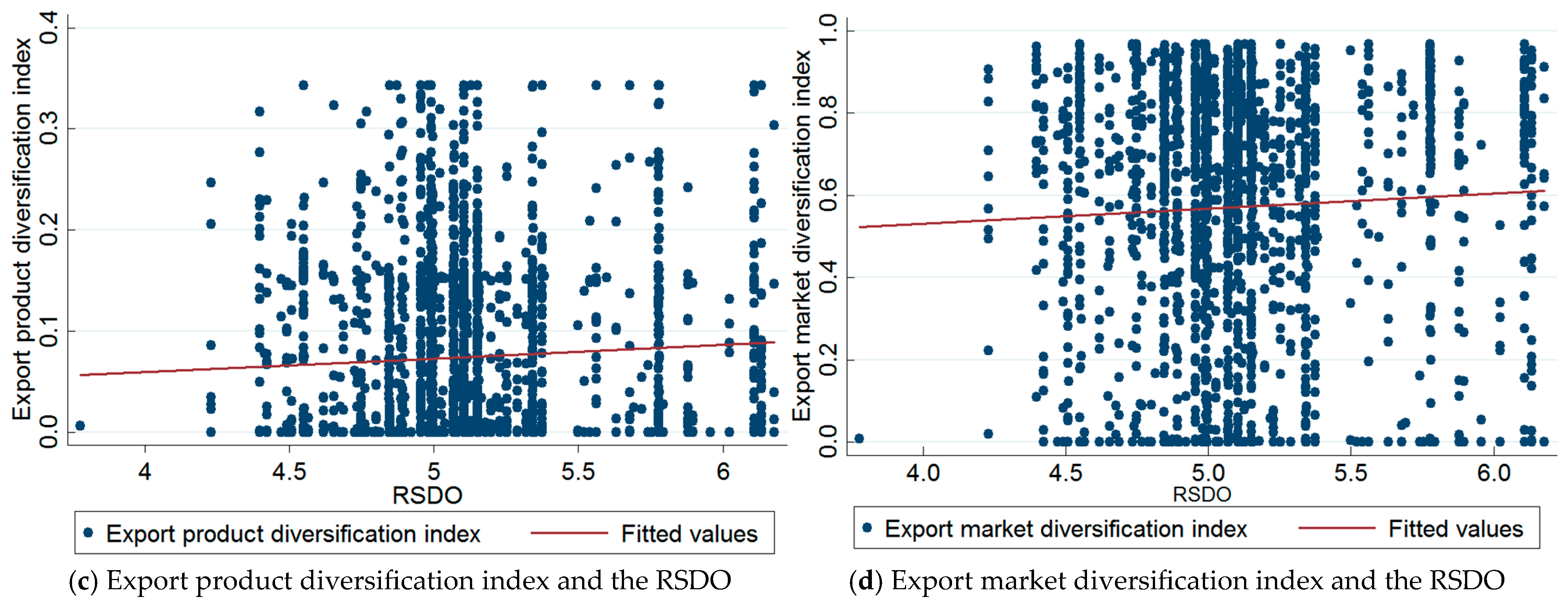

(2) Tobit model. Two of the measurement variables for export diversification, the export product diversification index and the export market diversification index, are continuous variables between 0 and 1. They are classified as “non-negative truncated data”; some values are 0, not following a normal distribution, making it impossible to directly use OLS regression. To address this, the Tobit model is introduced, which is known as a censored or truncated regression model and is one of the limited dependent variable regression models. Based on the left-censoring characteristic of the data, the Tobit model can set the rule that “values of the dependent variable equal to or below the threshold of 0 will be censored”. The standard Tobit model is specified as:

In the equation, represents the latent variable of the export product (or market) diversification index for the i-th enterprise; represents the observed value of the export product (or market) diversification index for the i-th enterprise; β1 is the effect of the RSDO on the enterprise’s export product (or market) diversification index; xi is the vector of control variables for the i-th enterprise; δ is the vector of estimated coefficients for the control variables; α is the constant term; εi is the random error term.

(3) The model’s endogeneity issue in Equations (3) and (4) must be considered and tested. Using “whether the party secretary of the prefecture-level city has been replaced (replacement = 1; no replacement = 0)” as an instrumental variable for the RSDO, the rationale is that the short tenure and promotion tournaments lead to a rational official’s optimal response of “immediately upon taking a new position, pushing harder and striving for quick results” [

41]. In the first half of 2013, various levels of government in China launched a wave of “streamlining administration, delegating powers, and improving services” reform. This reform became a key opportunity for new party secretaries to establish their achievements. It naturally became one of the main tasks for newly appointed party secretaries and local government officials to meet the demand for ‘short-term results’ and fully promote the RSDO. Therefore, the change in party secretaries in 2013 is significantly related to the local RSDO in 2014 but has no direct connection with the export behavior of wood-processing enterprises in 2014, thus meeting the homogeneity requirement for the instrumental variable. First, the two-step method of endogeneity Hausman test proposed by Wooldridge is selected to test the endogeneity problems of Equation (3) [

41]. In the first step, regression is carried out with the RSDO as the dependent variable and instrumental variable as well as other existing control variables as independent variables to obtain the residual term. In the second step, the residual term is incorporated into Equation (3). The results show that regression coefficients of the residual term are, respectively, −1.044 (

p-value being 0.721) and −0.679 (0.669) for the equation with the export product diversification index and export market diversification index as the dependent variable, indicating that the RSDO can be regarded as an exogenous variable. Second, using the “ivtobit” code in Stata 14.0 and the Wald test (null hypothesis: all explanatory variables are exogenous), the IV Tobit estimation for Equation (4) is conducted. The results show that the Wald statistics are 0.32 and 0.28, with

p-values of 0.5699 and 0.5974, respectively. So, we cannot reject the null hypothesis of “α = 0” for homogeneity, meaning there is no endogeneity issue in Equation (4) fitting, and the RSDO is not an endogenous variable. Therefore, subsequent empirical analyses will use the Tobit model to estimate and discuss results.

(4) The indirect effect testing method is the Bootstrap method. The testing method for indirect effects is similar to mediation, but there are still differences. Mediation effects assume that the explanatory variable

X significantly influences dependent

Y. However, indirect effects do not require this assumption because many indirect paths may exist [

42]. The sum of indirect effects from different paths may be close to 0, leading to no significant effect of

X on

Y. An initial exploration using the export market diversification index (

Y) shows that the RSDO (

X) has no significant effect on

Y, which cannot meet the requirements for mediation effect testing. Therefore, this study tests the indirect effect of the RSDO on the export behavior of wood-processing enterprises, identifying the impacting pathways of the reform. Currently, the most commonly used methods include stepwise testing, the Sobel test, and the Bootstrap method. Drawing on the research of Zhong et al. [

43], the Bootstrap method is chosen to test whether the RSDO affects the export behavior of wood-processing enterprises indirectly by promoting technological innovation and reducing operating costs.