Nature Deficit in the Context of Forests and Human Well-Being: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Contemporary societies experience a measurable nature deficit, although current research tools allow only for partial and imperfect diagnosis.

- Forest areas can play a significant role in mitigating nature deficit by providing ecosystem services, supporting human well-being, and strengthening social integration.

- Significant research gaps remain, particularly with regard to sustainable forest management, cultural contexts, health policy, and the long-term effects of contact with nature on health.

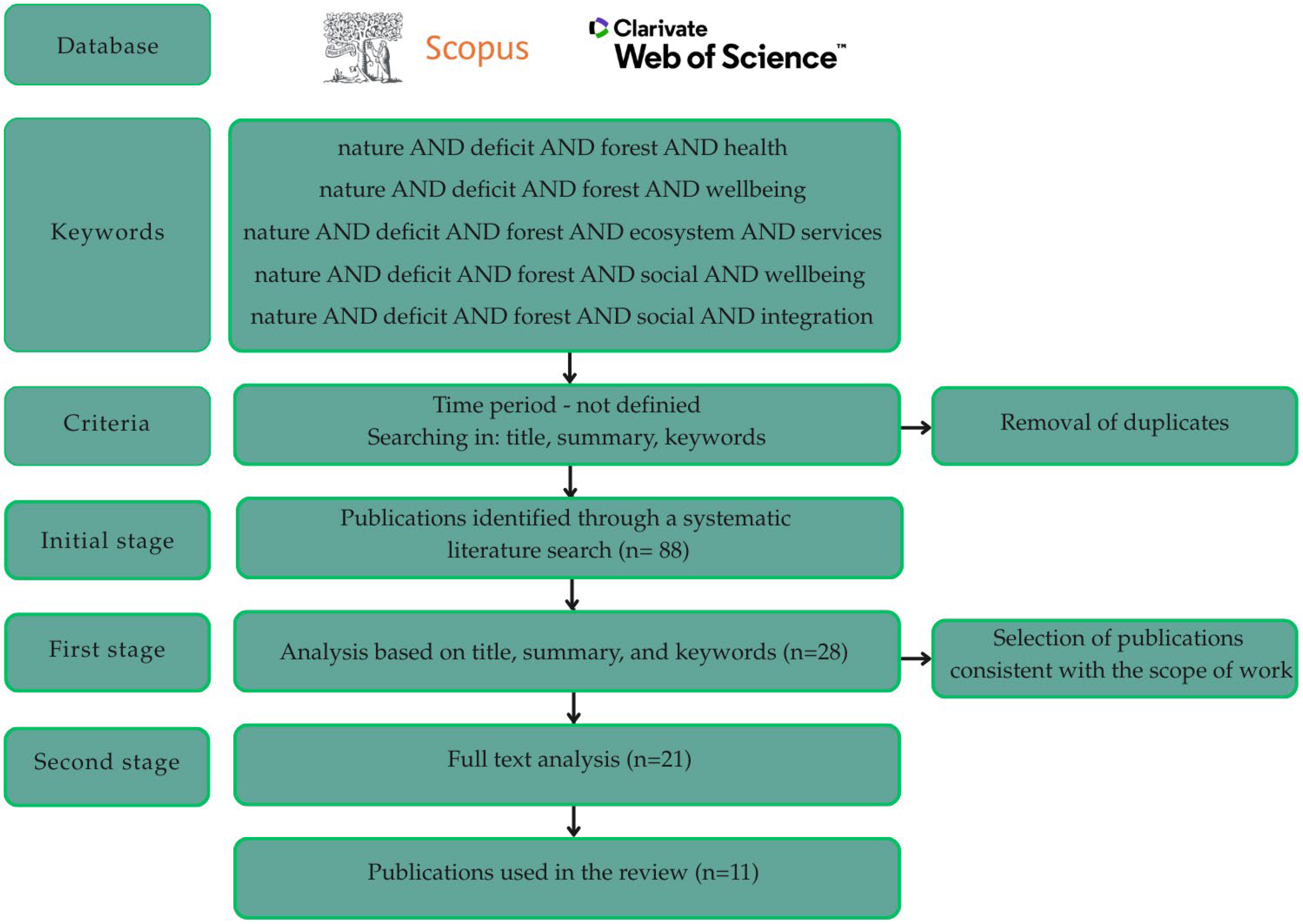

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

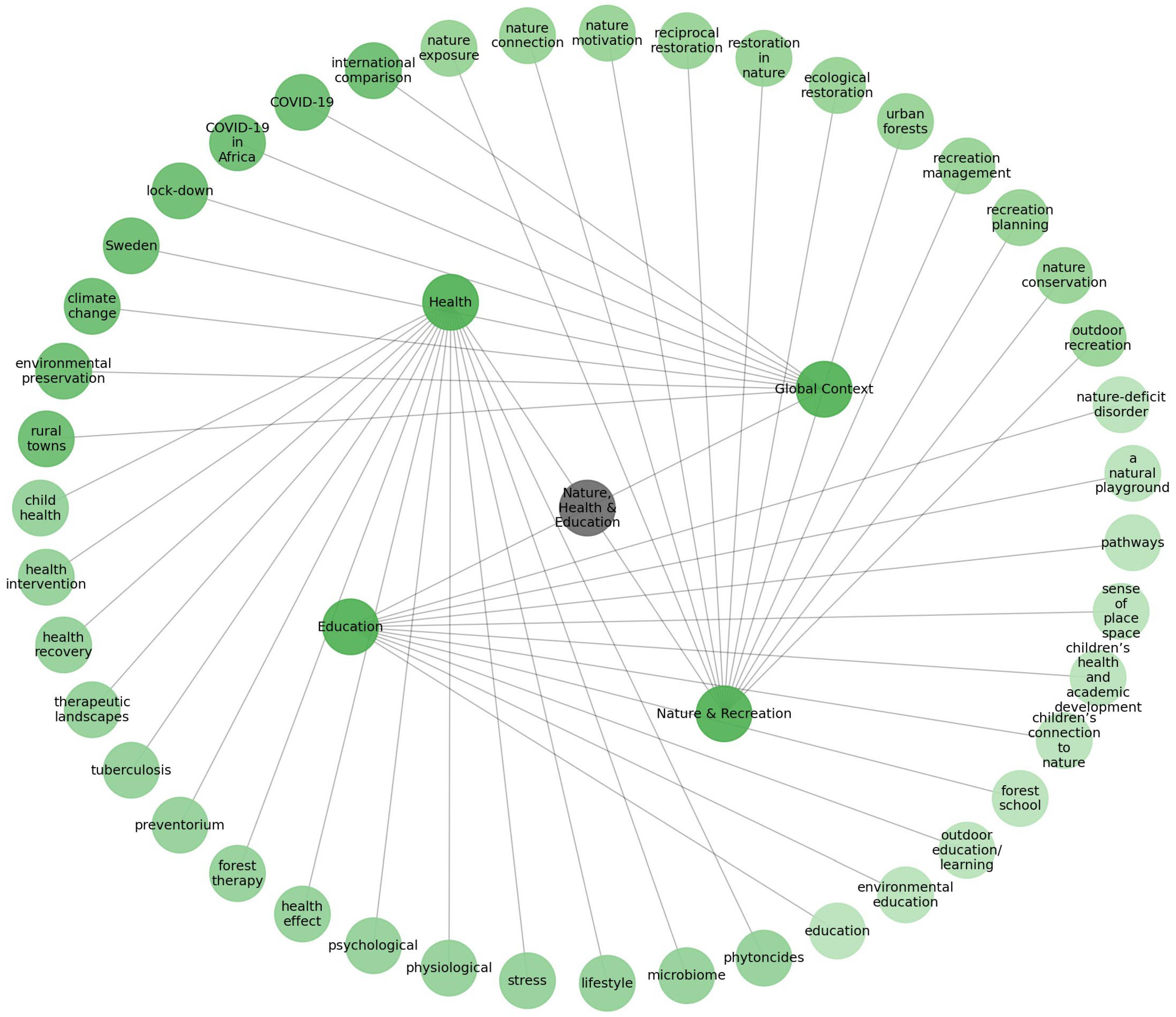

3.1. Bibliographic Overview

3.2. Key Scientific Articles in the Analyzed Area

3.3. Current State of Knowledge on Nature Deficit and Its Consequences for Human Physical, Mental, and Social Health

3.3.1. Definition and Main Causes of the Phenomenon

3.3.2. Consequences for Physical Health and Quality of Life

3.3.3. Consequences for Mental Health and Social Relationships

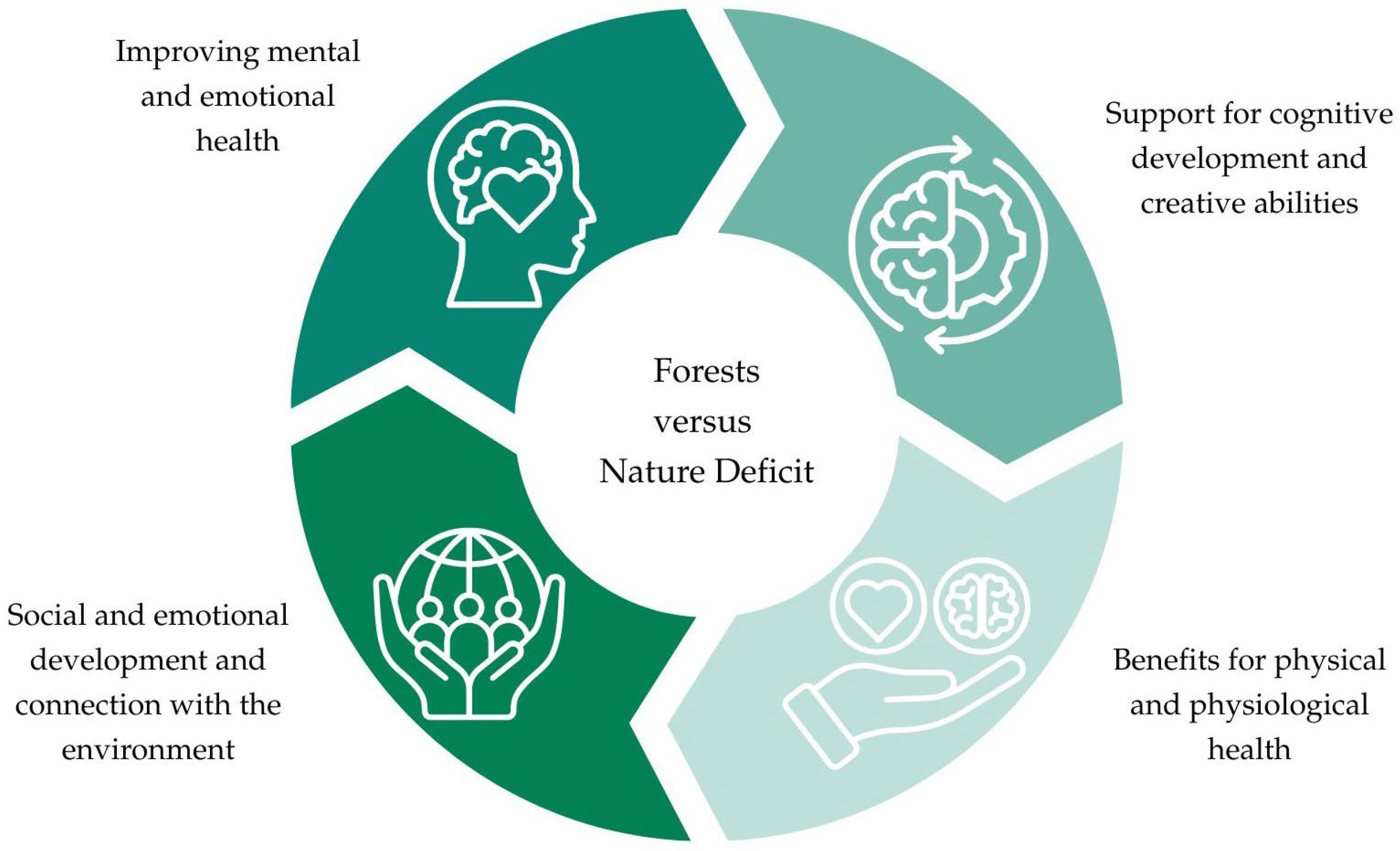

3.4. The Role of Forests as Natural Environments Counteracting Nature Deficit

3.4.1. Mechanisms of Forests’ Impact on Humans

3.4.2. The Importance of Forests in Today’s World

3.4.3. Improving Mental and Emotional Health Through Contact with Forests

3.4.4. Supporting Cognitive Development and Creative Abilities Through Contact with Forests

3.4.5. Benefits for Physical and Physiological Health Through Contact with the Forest

3.4.6. Social, Emotional Development and Connection with the Environment

4. Limitations of Research on Nature Deficit and the Role of Forests in Its Mitigation

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kazdin, A.E.; Vidal-González, P. Contact with Nature as Essential to the Human Experience: Reflections on Pandemic Confinement. Nat. Cult. 2021, 16, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küster, H. Geschichte der Landschaft in Mitteleuropa: Von der Eiszeit bis zur Gegenwart; CH Beck: Munich, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978 3 406 60848 3. [Google Scholar]

- Küster, H. Geschichte Des Waldes: Von der Urzeit bis zur Gegenwart; CH Beck: Munich, Germany, 2003; ISBN 3 406 50279 2. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, H.W. Ecology of the Heart: Understanding How People Experience Natural Environments. In Natural Resource Management; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 13–27. ISBN 9780429039706. [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin, H. Beyond Toxicity: Human Health and the Natural Environment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 20, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretty, J. How Nature Contributes to Mental and Physical Health. Spiritual. Health Int. 2004, 5, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, S. Vitamin G: Urban Green Planning for Human Health and Well-Being. In Proceedings of the Naturschutz & Gesundheit, Allianzen für Mehr Lebensqualität, Bonn, Germany, 26–27 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Louv, R. Vitamin N: The Essential Guide to a Nature-Rich Life; Hachette UK: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Šćepanović, S.; Joglekar, S.; Law, S.; Quercia, D.; Zhou, K.; Battiston, A.; Schifanella, R. Vitamin N: Benefits of Different Forms of Public Greenery for Urban Health. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.12998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, E.N.; Garcia, A.; Le, P. A Review of Nature Deficit Disorder (NDD) and Its Disproportionate Impacts on Latinx Populations. Environ. Dev. 2022, 43, 100732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Ming” Kuo, F.E. Nature-Deficit Disorder: Evidence, Dosage, and Treatment. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2013, 5, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandry, N. Nature Deficit Disorder. In Educating Young Children: Learning and Teaching in the Early Childhood Years; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; Volume 19, pp. 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, B.R. Nature-Deficit Disorder and the Effects on ADHD. Master’s Thesis, University of Wisconsin-Platteville, Platteville, WI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, R. Connection with Nature Is an Oxymoron: A Political Ecology of “Nature-Deficit Disorder”. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 48, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, C.E. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit Disorder. J. Environ. Educ. 2006, 37, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Palomino, M.; Taylor, T.; Göker, A.; Isaacs, J.; Warber, S. The Online Dissemination of Nature–Health Concepts: Lessons from Sentiment Analysis of Social Media Relating to “Nature-Deficit Disorder”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiffer, M.R.; James, P.; Chen, J.; Iyer, H.S.; Holland, I.; Roscoe, C.; Wilt, G.; Nethery, R.C.; Sun, Q.; Laden, F. Residential Greenness and Diabetes Incidence in Two Prospective Cohorts of US Women. Environ. Epidemiol. 2025, 9, e405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ideno, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Abe, Y.; Ueda, K.; Iso, H.; Noda, M.; Lee, J.-S.; Suzuki, S. Blood Pressure-Lowering Effect of Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, M.P.; DeVille, N.V.; Elliott, E.G.; Schiff, J.E.; Wilt, G.E.; Hart, J.E.; James, P. Associations between Nature Exposure and Health: A Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keith, R.J.; Hart, J.L.; Bhatnagar, A. Greenspaces And Cardiovascular Health. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 1179–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Q.; Yang, L.; He, M.; Gao, W.; Mar, H.; Li, J.; Wang, G. The Effects of Forest Therapy on the Blood Pressure and Salivary Cortisol Levels of Urban Residents: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, W.S.; Shin, C.S.; Yeoun, P.S. The Influence of Forest Therapy Camp on Depression in Alcoholics. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2012, 17, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonienko, K. Forest Bathing (Shinrin-Yoku) as an Example of Ecotherapeutic Interventions in a Group of Patients with Schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Spersonalizowana 2022, 1, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological Effects of Nature Therapy: A Review of the Research in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassini, S. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Nature Walk as an Intervention for Anxiety and Depression. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siah, C.J.R.; Goh, Y.S.; Lee, J.; Poon, S.N.; Ow Yong, J.Q.Y.; Tam, W.W. The Effects of Forest Bathing on Psychological Well-being: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurse 2023, 32, 1038–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Pahl, S.; Ashbullby, K.; Herbert, S.; Depledge, M.H. Feelings of Restoration from Recent Nature Visits. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.; Giles-Corti, B.; Wood, L.; Knuiman, M. Creating Sense of Community: The Role of Public Space. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Bamkole, O. The Relationship between Social Cohesion and Urban Green Space: An Avenue for Health Promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaźmierczak, A. The Contribution of Local Parks to Neighbourhood Social Ties. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Elands, B.; Buijs, A. Social Interactions in Urban Parks: Stimulating Social Cohesion? Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korcz, N.; Kamińska, A.; Ciesielski, M. Is the Level of Quality of Life Related to the Frequency of Visits to Natural Areas? Forests 2024, 15, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, A.R.; Rolland, C.G.; Rafoss, K.; Zoglowek, H. Norwegian Friluftsliv: A Way of Living and Learning in Nature; Waxmann Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largo-Wight, E.; Chen, W.W.; Dodd, V.; Weiler, R. Healthy Workplaces: The Effects of Nature Contact at Work on Employee Stress and Health. Public Health Rep. 2011, 126, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrins, S.P.; Varanasi, U.; Seto, E.; Bratman, G.N. Nature at Work: The Effects of Day-to-Day Nature Contact on Workers’ Stress and Psychological Well-Being. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 66, 127404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.M.; Ottley, K.M.; Arbuthnott, K.D.; Sevigny, P. Nature-Related Mood Effects: Season and Type of Nature Contact. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, C.; Gerard, J.; Arbuthnott, K.D. Nature Contact and Mood Benefits: Contact Duration and Mood Type. J. Posit. Psychol. 2019, 14, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.; Corazon, S.S.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Nature Exposure and Its Effects on Immune System Functioning: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M. How Might Contact with Nature Promote Human Health? Promising Mechanisms and a Possible Central Pathway. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, G.A. Regulation of the Immune System by Biodiversity from the Natural Environment: An Ecosystem Service Essential to Health. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 18360–18367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadvand, P.; Villanueva, C.M.; Font-Ribera, L.; Martinez, D.; Basagaña, X.; Belmonte, J.; Vrijheid, M.; Gražulevičienė, R.; Kogevinas, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Risks and Benefits of Green Spaces for Children: A Cross-Sectional Study of Associations with Sedentary Behavior, Obesity, Asthma, and Allergy. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobyłka, A.; Korcz, N. Importance of Urban Parks in Psychological Recovery: An Experiment with Young Adults from Poland. Quaest. Geogr. 2025, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, T.-M.; Hwang, J.-S.; Lin, S.-T.; Wu, C.; Tsai, M.-J.; Su, T.-C. Forest Bathing Is Better than Walking in Urban Park: Comparison of Cardiac and Vascular Function between Urban and Forest Parks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, H.; Wei, H.; He, X.; Ren, Z.; An, B. The Tree-Species-Specific Effect of Forest Bathing on Perceived Anxiety Alleviation of Young-Adults in Urban Forests. Ann. For. Res. 2017, 60, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korcz, N.; Janeczko, E.; Bielinis, E.; Urban, D.; Koba, J.; Szabat, P.; Małecki, M. Influence of Informal Education in the Forest Stand Redevelopment Area on the Psychological Restoration of Working Adults. Forests 2021, 12, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.scopus.com/pages/home?display=basic&zone=header&origin=#basic (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/smart-search (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Ciesielski, M.; Gołos, P.; Stefan, F.; Taczanowska, K. Unveiling the Essential Role of Green Spaces during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond—A Systematic Literature Review. Forests 2024, 15, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Referowska-Chodak, E. Management and Social Problems Linked to the Human Use of European Urban and Suburban Forests. Forests 2019, 10, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhmat, N.; Kolosova, O.; Demchenko, O.; Ivashchenko, I.; Strelchuk, V. Application of International Scientometric Databases in the Process of Training Competitive Research and Teaching Staff: Opportunities of Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, Google Scholar. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2022, 100, 4914–4924. [Google Scholar]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, L. Web of Science and Scopus: A Comparative Review of Content and Searching Capabilities. Charlest. Advis. 2009, 11, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Cheng, M.; Syamsi, M.N.; Lee, K.H.; Aung, T.R.; Burns, R.C. Accelerating the Nature Deficit or Enhancing the Nature-Based Human Health during the Pandemic Era: An International Study in Cambodia, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, and Myanmar, Following the Start of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Forests 2022, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depledge, M.H.; Stone, R.J.; Bird, W.J. Can Natural and Virtual Environments Be Used To Promote Improved Human Health and Wellbeing? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 4660–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowska, A. Forest School-a Forest Playground as a Remedy for Nature-Deficit Disorder in Children. e-mentor 2018, 76, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenseke, M.; Hansen, A.S. From Rhetoric to Knowledge Based Actions–Challenges for Outdoor Recreation Management in Sweden. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2014, 7, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabhan, G.P.; Orlando, L.; Smith Monti, L.; Aronson, J. Hands-On Ecological Restoration as a Nature-Based Health Intervention: Reciprocal Restoration for People and Ecosystems. Ecopsychology 2020, 12, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Mkandawire, M.; Niyigena, P.; Xotyeni, A.; Itamba, E.; Siame, S. Impact of COVID-19 Lock-Downs on Nature Connection in Southern and Eastern Africa. Land 2022, 11, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grose, M.J. Landscape and Children’s Health: Old Natures and New Challenges for the Preventorium. Health Place 2011, 17, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddon, J.R.; Durante, S.B. Nature Exposure Sufficiency and Insufficiency: The Benefits of Environmental Preservation. Med. Hypotheses 2018, 110, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.R.; Chang, J.; Lee, J.; Byeon, W.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.J. Perspectives on the Psychological and Physiological Effects of Forest Therapy: A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Forests 2022, 13, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudworth, D.; Lumber, R. The Importance of Forest School and the Pathways to Nature Connection. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2021, 24, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysomalidou, A.; Takos, I.; Spiliotis, I.; Xofis, P. The Participation of Teachers in Greece in Outdoor Education Activities and the Schools’ Perceptions of the Benefits to Students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| № | Title | DOI | In-Text Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Accelerating the Nature Deficit or Enhancing the Nature-Based Human Health during the Pandemic Era: An International Study in Cambodia, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, and Myanmar, following the Start of the COVID-19 Pandemic | https://doi.org/10.3390/f13010057 | [54] |

| 2 | Can Natural and Virtual Environments be used to Promote Improved Human Health and Wellbeing? | https://doi.org/10.1021/es103907m | [55] |

| 3 | Forest School—a Forest Playground as a Remedy for Nature-Deficit Disorder in Children | http://dx.doi.org/10.15219/em76.1381 | [56] |

| 4 | From Rhetoric to Knowledge Based Actions—Challenges for Outdoor Recreation Management in Sweden | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2014.09.004 | [57] |

| 5 | Hands-On Ecological Restoration as a Nature-Based Health Intervention: Reciprocal Restoration for People and Ecosystems | https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2020.0003 | [58] |

| 6 | Impact of COVID-19 Lock-Downs on Nature Connection in Southern and Eastern Africa | https://doi.org/10.3390/land11060872 | [59] |

| 7 | Landscape and Children’s Health: Old Natures and New Challenges for the Preventorium | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.08.018 | [60] |

| 8 | Nature Exposure Sufficiency and Insufficiency: The Benefits of Environmental Preservation | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2017.10.027 | [61] |

| 9 | Perspectives on the Psychological and Physiological Effects of Forest Therapy: A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression | https://doi.org/10.3390/f13122029 | [62] |

| 10 | The Importance of Forest School and the Pathways to Nature Connection | https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-021-00074-x | [63] |

| 11 | The Participation of Teachers in Greece in Outdoor Education Activities and the Schools’ Perceptions of the Benefits to Students | https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080804 | [64] |

| № | Area | Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lifestyle and chronic diseases | Obesity and diabetes—limitations of daily physical activity, living in environments that promote sedentary lifestyles, and exposure to surroundings full of stimuli and products that contribute to being overweight (so-called obesogenic environments) [55,59,60,61,64] |

| Cardiovascular and respiratory diseases—reduced exposure to greenery and lack of outdoor physical activity increase the risk of mortality from cardiovascular diseases [55] | ||

| 2 | Respiratory system | Increased risk of infections and allergies—limited early exposure to diverse microorganisms (especially soil-based) disrupts the maturation of the immune system, contributing to allergies and inflammatory conditions [59] |

| Exacerbation of respiratory diseases—air pollution worsens respiratory system functioning, while higher surrounding biodiversity has a protective effect [64] | ||

| Susceptibility to dust-borne diseases—limited contact with natural environments increases vulnerability to pathogens present in dust, including fungi causing coccidioidomycosis [55] | ||

| 3 | Immune system | Weakened immunity due to stress—contact with nature reduces stress levels and oxidative stress markers (MDA), supporting immune system functioning; isolation and restrictions contribute to the deterioration of physical health [62] |

| Vitamin D deficiency—limited exposure to sunlight reduces vitamin D synthesis, negatively affecting bone health and immune system functioning [64] | ||

| 4 | Visual system | Greater presence of greenery—for example, in the surroundings of schools, is associated with lower rates of vision degeneration [64] |

| 5 | Quality of life and vitality | Limited contact with nature (NEI)—reduced contact with nature (NEI) lowers overall well-being [61] |

| 6 | Lifestyle and general health | COVID-19 pandemic—lockdowns and restrictions reduced time spent outdoors, while simultaneously highlighting the need to return to nature as a source of health and recreation [54,59] |

| № | Area | Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Increased stress and reduced mental well-being | Stress and deteriorated mental health—higher stress levels, reduced mental and social well-being, decline in vitality, life satisfaction, and sense of happiness [54,59,60,64] |

| 2 | Mood and emotional disorders | Anxiety and fear—activation of the amygdala increases the sense of anxiety [63] |

| Anger and aggressive behaviors—intensified emotional reactions such as anger and aggression [64] | ||

| Rumination and sadness—increased tendency toward recurring negative thoughts [61] | ||

| Lowered mood and energy—limited contact with nature negatively affects cognitive abilities and mood, similarly to Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) [61] | ||

| 3 | Cognitive and developmental problems | Reduced creativity and imagination—limited contact with nature decreases creative abilities and imagination development [64] |

| Cognitive difficulties—weakened concentration, clarity of thought, and problem-solving skills [64] | ||

| Aggravation of ADHD symptoms—lack of green spaces and sleep deficiency related to insufficient daylight exacerbate symptoms [64] | ||

| 4 | Identity and social relationship disorders | Loss of sense of full humanity—weakened connection with the natural environment and deterioration of existential identity [63,64] |

| Poor social relationships—weak communication, limited cooperation, and fragile social bonds [64] | ||

| Weakened self-esteem—decline in self-confidence and independence [63] | ||

| Aversion to nature—reluctance toward nature observed among the digital generation [54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Korcz, N. Nature Deficit in the Context of Forests and Human Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Forests 2025, 16, 1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101537

Korcz N. Nature Deficit in the Context of Forests and Human Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Forests. 2025; 16(10):1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101537

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorcz, Natalia. 2025. "Nature Deficit in the Context of Forests and Human Well-Being: A Systematic Review" Forests 16, no. 10: 1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101537

APA StyleKorcz, N. (2025). Nature Deficit in the Context of Forests and Human Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Forests, 16(10), 1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101537