Abstract

The understanding of species distribution in Peru is limited, in part due to cartographic representations that traditionally use political rather than biogeographical boundaries. The objective of this study was to determine the distribution of Arecaceae species in the department of Amazonas by representing them in biogeographical regions. To this end, geographic information systems and global databases were used to map and analyze the species in four categories: Ecosystems Map, Ecoregions Map, Peru Climate Classification Map, and Protected Natural Areas Map. Subsequently, diversity metrics were estimated, revealing high diversity in Amazonas, with 22 genera and 90 species of Arecaceae representing 51.16% and 41.28% of the records in Peru, respectively. In addition, predominant genera and species were identified, and diversity was evaluated in biogeographic units. Of a total of 336,029 records, 45 genera were found, with Geonoma and Bactris being the most representative, and of the 218 species found in total, the records that stood out the most varied according to biogeographical regions. For each Biogeographic unit by category, different responses were obtained, for example, for Index Margalef, between 0.000 (low in Agricultural Area), 7.2489 (medium in Eastern Cordillera Real Montane Forests), and 13.2636 (high in Non-protected Areas). Similarly, for the Shannon–Wiener diversity index (), where values were obtained between 0.000 (low in Jalca (Andean High Grasslands), (medium in Reserved Zonez) and 3.7054 (high in Non-protected Areas). The results suggest high under-recording, evidencing gaps in knowledge and information, as analyses based on detailed studies of diversity in specific biogeographic categories in these other families, as well as future research to determine, for example, genomes and Hill numbers, will be carried out. The conclusions highlight the high correlation between the diversity metrics analyzed, confirm the theoretical validity, and allow us to recommend species richness and the Margalef Index as useful and relevant metrics due to their applicability and ease of interpretation. This study offers key information for decision makers in policies for the conservation of Arecaceae diversity and motivates us to project research of this type in other families in Peru.

1. Introduction

The Arecaceae family, traditionally known as palms, comprises about 2600 species distributed in 181 genera, found mainly in the tropical and subtropical forests of the world [1]. These species play a fundamental role in tropical ecosystems due to their abundance and diversity [2]. Also, palms have great economic value, as they are used as ornamental plants and as a source of food [3], in addition to other folkloric and phytochemical uses [4], altering the natural distribution of this family [5]. Arecaceae products support local economies and participate in international trade, making them a vital resource for many communities [6]. The fruits of many Arecaceae species are a source of food for both wildlife and indigenous communities and contribute to essential ecosystem services such as pollination and seed dispersal [7]. However, their natural distribution is restricted to certain areas. These pressures affect biodiversity globally, and Peru is no exception, where habitat loss and fragmentation is evident [8,9]. It has been demonstrated that some palm species adapt to natural environmental gradients at different spatial scales. These species are widely used and often exported to long distances, movements that blur the natural distribution patterns [10]; the understanding of patterns of palm distribution across gradients, therefore, requires extensive field work in order to contribute to the biogeography of tropical regions [11].

Despite their importance, there are important gaps in knowledge about the distribution of Arecaceae genera. For example, in the genus Attalea, the lack of adequate botanical material has hindered its correct identification [12]. In addition, lack of information, such as variable climate and terrain, can strongly affect the distribution of Arecaceae species and, thus, the inclusion of these variables into the analyses is warranted [13].

Arecaceae species are associated with specific habitats [14] and show significant morphological and functional variation [15]. Furthermore, anatomical knowledge of many species is still limited [16], which prevents a complete understanding of their global distribution [17]. Difficulties in the classification of Arecaceae species are aggravated by the tendency to represent their distribution considering political boundaries [18] instead of biogeographic trends or patterns, which reflect areas with relatively homogeneous ecological conditions or similarities at the biological level [19]. In the Peruvian context, studies such as the Analysis of the Ecological Cover of the National System of Natural Areas Protected by the State have provided limited information on species diversity in Peru’s ecoregions [20]. Similarly, the National Map of Ecosystems presents scarce data on the presence of species in Peruvian ecosystems [21].

Arecaceae of the peruvian Amazonas is an understudied family, for example, in 15 inventories conducted in remote areas of this region, 9397 specimens of different organisms were collected, but only one species of Arecaceae, Astrocaryum ciliatum, was recorded in the database [22]. In addition, 13 species of the genus Attalea were reported [12], and in another study, the species Ceroxylon parvum was found in the Seasonally Dry Tropical Forests [23]. Four species of the genus Ceroxylon were reported from Molinopampa district, Amazonas department, Peru: Ceroxylon parvifrons, Ceroxylon peruvianum, Ceroxylon quidiuense, and Ceroxylon vogelianum [24].

Given these knowledge gaps, it is essential to apply global databases such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, which contains detailed records of species, including Arecaceae. However, there is still a need to interpret these data in terms of biogeographic regions [25].

The use of Geographic Information Systems has proven to be effective tool for studying geographical distributions [26]. These tools facilitate decision making and optimize the use of resources [27] through different approaches to landscape assessment [28]. Geographic distribution models, which measure habitat suitability for a species [29], are essential in biogeography and conservation studies [30]. Among the most widely used models are MaxEnt, which predicts species distributions based on occurrence data [31], and CLIMEX, which delimits distribution thresholds [32].

One must consider that biogeographic units are regions that share a common evolutionary history that influence the distribution of species, characterized by a flora with shared elements different from other units [33], and that the ecoregions of Peru are geographic areas that have distinctive ecological, climatic, floristic, and faunal characteristics [34]. This research is framed in the relationship of the Arecaceae family with respect to the diversity found in these areas. In this context, we focused on the spatial representation of species of the family Arecaceae in the department of Amazonas in Peru, using global databases to facilitate biogeographic studies. The objective of this study was to determine the distribution of Arecaceae species in the different biogeographic regions of the Amazonas department by analyzing global databases like biodiversity information facility (GBIF) and Trópicos.org. For this purpose, species were represented in biogeographic regions and alpha diversity indices were estimated according to their distribution in these categories. Finally, we elucidate the relevance of the metrics in diversity studies for the Amazon region and at the level of biogeographic regions, as well as determine the implications of the study in the context of Peruvian regulations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The Amazon is home to approximately 50% of all palm genera [35]. In this regard, the department of Amazonas, located in the Peruvian Amazon [36] was chosen to study the representation of species of the Arecaceae family in biogeographic maps. This department covers approximately 42,050.37 km2 and presents an altitudinal gradient from 120 m asl in the north to 4900 m asl in the south [37]. Located in northeastern Peru, it borders Ecuador to the north (Figure 1); it also borders the with the departments of Cajamarca to the west, La Libertad to the south, San Martín to the southeast, and Loreto to the east.

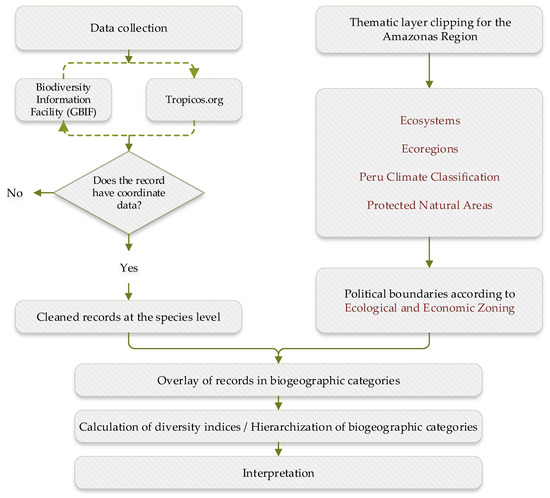

Figure 1.

Methodological outline for the analysis of family Arecaceae in Amazonas, northeastern Peru.

2.2. Data Collection and Cleaning

The methodology used is shown in Figure 1. The data were downloaded from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility database https://www.gbif.org/ (accessed on 13 August 2024), to obtain information on the records of species of the Arecaceae family, such as scientific name, genera, family, geographic coordinates, altitude, and origin (continent, country, state, or province), among other data. Records at the subspecies level were excluded, limiting the analysis exclusively to the species level. Following the recommendations of [31], records were compared and contrasted with the Tropicos.org database https://www.tropicos.org/home (accessed on 20 August 2024). Then, the data were cleaned according to the method of García and collaborators [38], using spreadsheet filters to eliminate incomplete records, such as those without geographic coordinates and incorrect or questionable data. In addition, we verified that the coordinates were within the political boundaries of the Amazonas department.

2.3. Representation of Species in Biogeographic Regions

Under the consideration that biogeographic units are corresponding in regions that share a common evolutionary history [33], several thematic layers were used in ArcGIS 10.8 software for the department of Amazonas. The layers were:

- National Map of Ecosystems of Peru [21,39], downloaded from the geoserver of the Ministry of Environment (https://geoservidor.minam.gob.pe/recursos/intercambio-de-datos/, accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Map of Ecoregions based on the classification of Olson et al., 2001 [40], obtained from the World Wildlife Fund (WWF, https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/terrestrial-ecoregions-of-the-world, accessed on 20 August 2024) and adapted for Peru in the Analysis of the Ecological Cover of SINANPE [20].

- Climate Classification Map of Peru [41] (average 1981–2010) from the National Service of Meteorology and Hydrology of Peru (SENAMHI, https://idesep.senamhi.gob.pe/geonetwork/srv/spa/catalog.search#/home, accessed on 20 August 2024)

- Map of Protected Natural Areas, elaborated from the geographic viewer of the National Service of Natural Areas Protected by the State (SERNANP, https://geo.sernanp.gob.pe/visorsernanp/, accessed on 20 August 2024) and the Regional Conservation System (SICRE) of the department of Amazonas.

The thematic layers were clipped using the political boundaries established in the ecological and economic zoning of Amazonas [42]. The resulting maps are shown in Figure 2. The cleaned database was adapted for use in geographic information systems [38], which allowed overlaying of the geographic records of the species in the biogeographic categories. This finally made it possible to produce tables accounting for the number of species and the number of species records for each genera of the family Arecaceae in each biogeographic category.

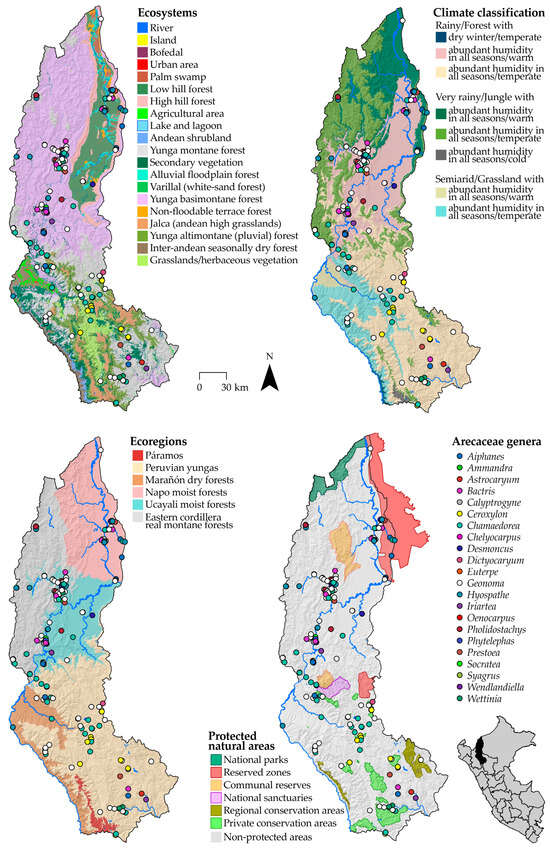

Figure 2.

Representation of species of the family Arecaceae in biogeographic regions in the department of Amazonas, Peru.

2.4. Estimation of Diversity Metrics

Alpha diversity (α) is defined as the species richness in a given habitat or the number of species in a given locality [43]. To study species richness, the Margalef Diversity Index () was chosen, which is easily calculated with Equation (1) using a logarithmic relationship [44]:

where

S: Number of species recorded; it is equivalent to species richness (R).

N: Total number of individuals summed from all species, equivalent to abundance (A).

Studying α in this way implies a limitation, since it does not take into account the evenness of the species [45]. For this reason, the analysis was complemented with the Shannon–Wiener diversity Index (), which, in addition to being widely used, incorporates species evenness in its calculation. This index was calculated with Equation (2) [46,47]:

where

: Proportion of species (Number of individuals of species i with respect to the total number of individuals of the S species in a community).

S: Total number of species in the community.

2.5. Data Analysis

To interpret the Shannon–Wiener diversity Index, we followed the guidelines of Margalef 1972 [48], who suggest that this index typically varies between 1.5 and 3.5. We considered “low diversity” when the index is less than 2, “medium diversity” between 2 and 3.5, and “high diversity” for values greater than 3.5; for example, the lower the uncertainty in the prediction of the species to which a randomly chosen individual belongs, the lower the value of the index and, therefore, the diversity of the community is considered low. In the case of the Margalef Index, “low biodiversity” was interpreted as “low biodiversity” for values less than 2, and “high biodiversity” for values greater than 5 [49]. To compare the diversity metrics, Spearman’s correlation coefficient (ρ) was calculated between pairs of indices.

3. Results

3.1. Biogeographic Representation of the Species of the Family Arecaceae in the Department of Amazonas

3.1.1. Brief Global, National and Departmental Overview

The Arecaceae family is distributed throughout the world, except at the poles, and it is concentrated in the tropics, mainly in South America, in countries such as Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Central America, and Mexico. According to our analysis, the Arecaceae family includes 251 genera with a total of 2836 species and 1,078,558 species records worldwide (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of the number of genera and species of the family Arecaceae by geographic range based on data from [50].

In Peru, the Arecaceae family is composed of 43 genera that include 218 species, with a total of 336,029 species records, which corresponds to 7.69% of the species worldwide, 17.13% of the genera, and 31.16% of the global records. However, 0.14% of the records from Peru lack georeferencing. Table 2 shows the genera recorded in Peru, ordered according to the number of species in each genus. Geonoma is the most diverse genera, representing 13.76% of the total number of species, followed by Bactris with 11.93%. Some genera, such as Aphandra and Cocos, have few species records, but with abundant information, suggesting that a low number of species does not necessarily imply a low number of records.

Table 2.

Distribution of genera and number of species of the family Arecaceae in Peru based on data from [50].

In the department of Amazonas, 90 species distributed in 22 genera have been identified, totaling 665 records, which represents 0.20% of the records in Peru. Despite the low number of records, Amazonas contains 51.16% of the genera and 41.28% of the species of Arecaceae in Peru, which shows evidence of gaps in knowledge and information in the department. Geonoma is the most abundant genus in species (20%) and number of records (39.4%, Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of genera and number of species of the Arecaceae family in the department of Amazonas based on data from [50].

3.1.2. Biogeographic Distribution of Species in the Department of Amazonas

We constructed species distribution maps of four categories representing ecosystems, ecoregions, climate, and protected natural areas, showing species richness (R) and abundance (A) classes (Figure 2, Table 4). The biogeographic units are listed in decreasing order of species richness.

Table 4.

Species richness and abundance by biogeographical regions in the department of Amazonas based on data from GBIF [50].

In the Ecosystems Map category, species were recorded in 15 ecosystems, with the Yunga Basimontane Forest (R = 59) and the Yunga Montane Forest (R = 35) having the highest species richness. In contrast, the Jalca, Agricultural Area, and Urban Area ecosystems had only one species recorded (R = 1).

In the Ecoregions Map, five ecoregions have species records. The ecoregions Ucayali Moist Forests (R = 57) and Eastern Cordillera Real Montane Forests (R = 36) have the highest species richness, while the Marañón Dry Forests have the lowest species richness (R = 6).

For the Peru Climate Classification Map, species were identified in six climate types. The Rainy/Forest with Abundant Humidity in All Seasons/Warm (R = 62) and Rainy/Forest with Abundant Humidity in All Seasons/Temperate (R = 34) climates are the most diverse, while the Semiarid/Grassland with Abundant Humidity in All Seasons/Warm type has only one species recorded (R = 1).

In the Protected Natural Areas Map, species were recorded in three types of protected natural areas. Non-protected Areas (R = 86) showed the highest species richness, followed by Reserved Zones (R = 20) and Private Conservation Areas (R = 5). These data show the low number of records within protected areas, even though Amazonas has 26 natural protected areas covering 592,876.64 hectares, which means that a large proportion of its territory is under protection (15.12%). Finally, in all biogeographic regions, the most recorded species is Geonoma stricta.

3.2. Diversity Indices According to Species Distribution

Table 5 shows the diversity indices for the biogeographic categories, ordered in decreasing order according to the Shannon–Wiener diversity index, excluding those biogeographic units with no species record. For biogeographic units with only one species record, the Margalef Index restricts its equation, so there is no estimate.

Table 5.

Estimation and valuation of biodiversity in biogeographic regions.

The values and ranking of the biogeographic units with the Margalef Index were generally consistent with those of the Shannon–Wiener diversity index, with one exception in the Ecosystems Map category, where unit 9 has a higher value than unit 8 in the Margalef Index, opposite to what was found with the Shannon–Wiener diversity index. Both metrics coincided completely only in Protected Natural Areas Map, while in the other categories their valuations varied partially due to the different interpretation approaches of each index. Nevertheless, the classification is consistent with species richness (Table 4).

It is relevant that the Non-protected Areas biogeographic unit is the only one with high diversity according to both indexes, reflecting the highest concentration of records outside protected areas.

4. Discussion

4.1. Representation and Distribution of Species in Biogeographic Categories in the Department of Amazonas

This study revealed the existence of at least 2836 species and 251 genera of the family Arecaceae worldwide, exceeding previous estimates of 2600 species by 181 genera [1,3]. This increase can be attributed to the discovery of new species in recent years and the increase in the number of records in global databases.

Although the department of Amazonas is recognized for its wide biological diversity [51] and high rate of endemism [42]. Nevertheless, Amazonas represents 41.28% of the species and 51.16% of the genera in the country.

Traditionally, species representations on maps have been made according to political boundaries and not biogeographic boundaries, which tend to underestimate species richness and endemism in the Amazon. This generates the need to improve data collection and accuracy in the Peruvian Amazon and to prioritize biogeographic approaches that can help to more accurately reflect the distribution of species in the department of Amazonas and Peru in general, using research with a multidisciplinary approach.

4.2. Evaluation of the Use of Diversity Metrics According to Species Distribution

The biodiversity metrics employed in this study (species richness, abundance, Shannon–Wiener diversity index and Margalef Index) are dynamic, as has been demonstrated by Magurran [52]; this supports the coherence and concordance when classifying biogeographic units with these metrics. As in previous studies, the relationships between these metrics were observed to be nonlinear, which is consistent with the analysis of [53], who showed that the Shannon–Wiener diversity index follows a concave curve in its relationship with species richness, growing rapidly in the early stages and then stabilizing.

In this study, the Shannon–Wiener index ranged from 0 to 3.71, with an average of 2.13, validating the theoretical range of between 1.5 and 3.5 [48]. These results suggest that, although the index values evenness and evenness, species richness has a greater influence on the index than abundance, this is supported by the slightly higher correlation of species richness with the Shannon–Wiener diversity index. Similarly, the Margalef Index exhibited a higher correlation with species richness, this suggests that this index is also highly sensitive to specific richness [54].

We highlight that the biogeographic unit Non-protected Areas obtained a high diversity valuation with both indices, evidencing the concentration of species outside protected areas. This undoubtedly warrants reflection on the representativeness of protected areas in terms of biodiversity conservation or the difficulties that exist for the registration of species in these areas.

4.3. Relevance of Metrics in Diversity Studies

We suggest that biodiversity metrics should be interpreted with caution and caution due to variations in interpretation frameworks. In this study, Shannon–Wiener diversity index values were interpreted according to the criteria of [48], whereas other studies have used slightly different scales [55,56]. Undoubtedly, the choice of an interpretive framework significantly influences the assessment of diversity and, therefore, management recommendations.

In the specialized literature, there is a wide debate on which metric is most relevant for assessing biological diversity. Although species richness is widely used and recommended, the Shannon–Wiener diversity index has gained popularity due to its ability to incorporate abundance, but it is not the best diversity statistic [52]. This is because its biological interpretation is difficult and the logarithmic transformation constitutes mathematical limitations [54]. In comparison, the Margalef Index, although not often used, offers a simple and effective alternative for assessing alpha diversity. In this context, species richness is the most meritorious indicator if comparison criteria, such as discriminant capacity, sensitivity to sample size, uniformity, ease of calculation, and frequency of use, are evaluated [52]. In this study, species richness produced consistent biogeographic unit rankings and was easy to calculate, suggesting that it should be preferred as an indicator in future diversity assessment studies.

4.4. Implications of the Study in the Context of Peruvian Regulations

The results of this study show a low record of Arecaceae species in natural protected areas, while most of the records are found outside of them (Table 4). This finding is worrisome, because protected areas in Peru are established precisely to conserve biological diversity (Law of Natural Protected Areas, Law N°26834, 1997). The lack of records in these areas could be an indicator of insufficient georeferenced data collection during the studies that support their establishment.

The representation of species on biogeographic maps has the potential to more accurately inform conservation and management decisions. Information obtained from the Ecosystems Map and the Ecoregions Map can help update ecological and economic zoning studies, which is fundamental for defining sustainable use categories (Supreme Decree N°087-2004-PCM, 2004). In addition, the distribution data in the Protected Natural Areas Map can be valuable for identifying priority areas for the expansion or establishment of new protected areas.

In terms of public investment, the Ministry of Environment (MINAM) guidelines for the formulation of conservation projects in the typologies of ecosystems, species and support for the sustainable use of biodiversity (Ministerial Resolution N°178-2019-MINAM, 2019) require that initiatives focus on priority ecosystems according to the norm. However, the results of this study suggest that the prioritization of ecosystems should consider the specific characteristics of species families, such as Arecaceae, which could optimize conservation and management decisions. Integrating knowledge of the distribution of species in different biogeographic regions can improve technical and regulatory guidelines, promoting more informed and effective decisions in biodiversity conservation.

5. Conclusions

The representation of species of the Arecaceae family in biogeographic regions in the department of Amazonas highlights its high diversity. Specifically, Amazonas is home to 22 genera and 90 species of Arecaceae, representing 51.16% and 41.28%, respectively, of the genera and species recorded in Peru in world databases. However, the number of records only constitutes 0.2% of the national records, which is evidence of high under-reporting and suggests gaps in knowledge and information in this important department of the Peruvian Amazon.

These results suggest that certain genera and species are better represented probably because of the ease of identification or availability in databases, compared to species that have limited distribution or are less documented.

Regarding diversity in specific biogeographic categories, these results indicate that species richness of the Arecaceae family is more concentrated outside protected areas and in certain humid and forest ecosystems. This has important implications for the design of biodiversity conservation and management strategies in the department.

The diversity measures used were highly correlated and provided concordant and consistent classifications of biogeographic units. However, species richness and the Margalef Index stand out for their ease of estimation and interpretation and are, therefore, essentially useful in regional diversity studies. Since both metrics allow consistent and coherent classifications, we recommend their choice for future research, mainly in areas with limited data or when rapid diversity analyses are required.

Finally, the biogeographic unit Non-protected Areas is the only one classified with high diversity in the Protected Natural Areas Map, evidence of the need to strengthen the conservation approach in the department of Amazonas and in Amazonia in general.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M. and E.A.; methodology, F.M., L.G. and E.A.; J.V. and E.A.; validation, J.V., L.G. and E.A.; formal analysis, G.A.G. and E.A.; investigation, F.M., J.-W.C.-C. and E.A.; resources, F.M. and J.-W.C.-C.; data curation, J.-W.C.-C., J.V., L.G. and E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M. and E.A.; writing—review and editing, F.M., J.-W.C.-C., J.V., L.G., G.A.G. and E.A.; visualization, G.A.G.; supervision, J.V., L.G. and E.A.; project administration, F.M., J.-W.C.-C. and E.A.; funding acquisition, E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by PROCIENCIA, grant number CONTRATO N° PE501083491-2023-PROCIENCIA (APIGEN). The APC was funded by Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Emilio, T.; Lamarque, L.J.; Torres-Ruiz, J.M.; King, A.; Charrier, G.; Burlett, R.; Conejero, M.; Rudall, P.J.; Baker, W.J.; Delzon, S. Embolism Resistance in Petioles and Leaflets of Palms. Ann. Bot. 2019, 124, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roncal, J.; Francisco-Ortega, J.; Asmussen, C.B.; Lewis, C.E. Molecular Phylogenetics of Tribe Geonomeae (Arecaceae) Using Nuclear DNA Sequences of Phosphoribulokinase and RNA Polymerase II. Syst. Bot. 2005, 30, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, F.G.; de Araújo, F.F.; de Paulo Farias, D.; Zanotto, A.W.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M. Brazilian Fruits of Arecaceae Family: An Overview of Some Representatives with Promising Food, Therapeutic and Industrial Applications. Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 109690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayokun-nun Ajao, A.; Moteetee, A.N.; Sabiu, S. From Traditional Wine to Medicine: Phytochemistry, Pharmacological Properties and Biotechnological Applications of Raphia Hookeri G. Mann & H. Wendl (Arecaceae). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 138, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiserhardt, W.L.; Svenning, J.C.; Kissling, W.D.; Balslev, H. Geographical ecology of the palms (Arecaceae): Determinants of diversity and distributions across spatial scales. Ann. Bot. 2011, 108, 1391–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.J.; Savolainen, V.; Asmussen-Lange, C.B.; Chase, M.W.; Dransfield, J.; Forest, F.; Harley, M.M.; Uhl, N.W.; Wilkinson, M. Complete Generic-Level Phylogenetic Analyses of Palms (Arecaceae) with Comparisons of Supertree and Supermatrix Approaches. Syst. Biol. 2009, 58, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadini, R.F.; Fleury, M.; Donatti, C.I.; Galetti, M. Effects of Frugivore Impoverishment and Seed Predators on the Recruitment of a Keystone Palm. Acta Oecologica 2009, 35, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.; Fuller, R.; Brooks, T.; Watson, J. The Ravages of Guns, Nets and Bulldozers; Macmillan Publishers Limited: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pykälä, J. Habitat Loss and Deterioration Explain the Disappearance of Populations of Threatened Vascular Plants, Bryophytes and Lichens in a Hemiboreal Landscape. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 18, e00610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichgelt, T.; West, C.K.; Greenwood, D.R. The Relation between Global Palm Distribution and Climate. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roncal, J.; Borchsenius, F.; Asmussen-Lange, C.B.; Balslev, H. Divergence Times in the Tribe Geonomateae (Arecaceae) Coincide Qith Tertiary Geological Events. Divers. Phylogeny Evol. Monocoltiledons 2010, 245–265. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez del Castillo, Á.M.; Mejía Carhuanca, K.M.; Rojas-Fox, J.V.; Moraes Ramírez, M.; Sánchez-Márquez, M.d.F.; Pintaud, J.-C. Diversidad de Especies de Attalea (ARECACEAE) En El Perú, 1st ed.; Rodríguez del Castillo, Á.M., Ed.; Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonía Peruana: Tarapoto, Perú, 2018; ISBN 9786124372063. [Google Scholar]

- Boll, T.; Svenning, J.C.; Vormisto, J.; Normand, S.; Grández, C.; Balslev, H. Spatial Distribution and Environmental Preferences of the Piassaba Palm Aphandra Natalia (Arecaceae) along the Pastaza and Urituyacu Rivers in Peru. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 213, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, P.B.; Horn, J.W.; Fisher, J.B. The Anatomy of Palms: Arecaceae—Palmae; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Balslev, H.; Bernal, R.; Fay, M.F. Palms—Emblems of Tropical Forests. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 182, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Hazra, M.; Mahato, S.; Spicer, R.A.; Roy, K.; Hazra, T.; Bandopadhaya, M.; Spicer, T.E.V.; Bera, S. A Cretaceous Gondwana Origin of the Wax Palm Subfamily (Ceroxyloideae: Arecaceae) and Its Paleobiogeographic Context. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2020, 283, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.D.; Feltus, F.A.; Paterson, A.H.; Bailey, C.D. Novel Nuclear Intron-Spanning Primers for Arecaceae Evolutionary Biology. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2008, 8, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, B.; Pitman, N.; Roque, J. Introducción a Las Plantas Endémicas Del Perú. Rev. Peru. Biol. 2006, 13, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MITECO, (Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico) Regiones Biogeográficas Terrestres y Regiones Marinas. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/biodiversidad/servicios/banco-datos-naturaleza/informacion-disponible/regiones_biogeograficas_descargas.html (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- CDC-UNALM (Centro de Datos para la Conservación—Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina); TNC (The Nature Conservancy). Análisis Del Recubrimiento Ecológico Del Sistema Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas Por El Estado; CDC-UNALM/TNC: Lima, Perú, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MINAM (Ministerio del Ambiente). Mapa Nacional de Ecosistemas Del Perú. Memoria Descriptiva, 1st ed.; MINAM: Lima, Perú, 2019.

- Torres Montenegro, L.A.; Ríos Paredes, M.A.; Pitman, N.C.A.; Vriesendorp, C.F.; Hensold, N.; Mesones Acuy, Í.; Dávila Cardozo, N.; Huamantupa, I.; Beltrán, H.W.; García-Villacorta, R.; et al. Sesenta y Cuatro Nuevos Registros Para La Flora Del Perú a Través de Inventarios Biológicos Rápidos En La Amazonía Peruana. Rev. Peru. Biol. 2019, 26, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa Cruz, L.; Pintaud, J.-C.; Sanín, M.J.; Rodríguez Rodríguez, E.F. Nuevo Registro de Ceroxylon Parvum (Arecaceae) En El Perú. Arnaldoa 2018, 25, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- García-Pérez, A.; Rubio Rojas, K.B.; Meléndez Mori, J.B.; Corroto, F.; Rascón, J.; Oliva, M. Estudio Ecológico de Los Bosques Homogéneos En El Distrito de Molinopampa, Región Amazonas. Rev. Investig. Agroproducción Sustentable 2018, 2, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropicos.org., (Missouri Botanical Garden). Available online: https://tropicos.org (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Antwi, E.K.; Krawczynski, R.; Wiegleb, G. Detecting the Effect of Disturbance on Habitat Diversity and Land Cover Change in a Post-Mining Area Using GIS. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 87, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilaris, A.; Kartakoullis, A.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. A Review on the Practice of Big Data Analysis in Agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 143, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasov, O.; Vieira, A.A.B.; Külvik, M.; Chervanyov, I. Landscape Coherence Revisited: GIS-Based Mapping in Relation to Scenic Values and Preferences Estimated with Geolocated Social Media Data. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 111, 105973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, R.G.; Felicísimo, Á.M.; Muñoz, J. Modelos de Distribución de Especies: Una Revisión Sintética. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2011, 84, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. Species Distribution Modeling. Geogr. Compass 2018, 4, 490–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrina Sánchez, A.; Rojas Briceño, N.B.; Bandopadhyay, S.; Ghosh, S.; Torres Guzmán, C.; Oliva, M.; Guzman, B.K.; Salas López, R. Biogeographic Distribution of Cedrela spp. Genus in Peru Using Maxent Modeling: A Conservation and Restoration Approach. Diversity 2021, 13, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneros, J.; Tonnang, H.E.Z.; Juarez, H.; Kroschel, J. Distribución Geográfica y Potencial de Phthorimaea Operculella (Zeller) (Lepidóptera: Gelechiidae) Usando CLIMEX. LIV Conv. Nac. Entomol. 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A. Biogeographical Units Matter. Aust. Syst. Bot. 2018, 30, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beraún Chaca, J.J.; Villanueva Fernández, H.S. Clasificación de las Regiones Naturales del Perú; COLEGIO DE GEÓGRAFOS DEL PERÚ: Lima, Perú, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, A.; Galeano, G.; Bernal, R. Field Guide to the Palms of the Americas, 1st ed.; Princenton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1995; ISBN 9780691656120. [Google Scholar]

- MINAM (Ministerio del Ambiente). Mapa de Deforestación de La Amazonía Peruana 2000; Ministerio del Ambiente: Lima, Perú, 2009.

- Rojas Briceño, N.B.; Cotrina Sánchez, D.A.; Barboza Castillo, E.; Barrena Gurbillón, M.A.; Sarmiento, F.O.; Sotomayor, D.A.; Oliva, M.; Salas López, R. Current and Future Distribution of Five Timber Forest Species in Amazonas, Northeast Peru: Contributions towards a Restoration Strategy. Diversity 2020, 12, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L.; Veneros, J.; Chavez, S.G.; Oliva, M.; Rojas-Briceño, N.B. World Historical Mapping and Potential Distribution of Cinchona spp. in Peru as a Contribution for Its Restoration and Conservation. J. Nat. Conserv. 2022, 70, 126290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINAM (Ministerio del Ambiente). Definiciones Conceptuales de Los Ecosistemas Del Perú; MINAM: Lima, Perú, 2018.

- Olson, D.M.; Dinerstein, E.; Wikramanayake, E.D.; Burgess, N.D.; Powell, G.V.N.; Underwood, E.C.; Amico, J.A.D.; Itoua, I.; Strand, H.E.; Morrison, J.C.; et al. Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth. Bioscience 2001, 51, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SENAMHI (Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú). Climas Del Perú. Mapa de La Clasificación Climática Nacional. Resumen Ejecutivo; SENAMHI: Lima, Perú, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IIAP (Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonía Peruana); GRA (Gobierno Regional Amazonas). Zonificación Ecológica y Económica Del Departamento de Amazonas, 1st ed.; IIAP: Lima, Perú, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, R.H. Vegetation of the Siskiyou Mountains, Oregon and California. Ecol. Monogr. 1960, 30, 279–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalef, R. La Teoría de La Información En Ecología. Mem. La Real Acad. Cienc. Y Artes Barc. 1957, 3, 373–449. [Google Scholar]

- Ferriol Molina, M.; Merle Farinós, H.B. Los Componentes Alfa, Beta y Gamma de La Biodiversidad. Aplicación Al Estudio de Comunidades Vegetales; Universitat Politècnica de València: Valencia, Spain, 2012; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Tukiainen, H.; Kiuttu, M.; Kalliola, R.; Alahuhta, J.; Hjort, J. Landforms Contribute to Plant Biodiversity at Alpha, Beta and Gamma Levels. J. Biogeogr. 2019, 46, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalef, R. Homage to Evelyn Hutchinson, or Why There Is an Upper Limit to Diversity. Trans. Connect. Acad. Arts Sci. 1972, 44, 211–235. [Google Scholar]

- AECID (Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo). Estimación e Interpretación de Indicadores de Biodiversidad Forestal Considerando La Información de Los Inventarios Forestales Nacionales, 1st ed.; Aguilar, I., Ed.; AECID: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility). GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/ (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Montesinos-Tubée, D.B. Diversidad Florística En El Complejo Arqueológico La Bóveda, En El Sur Del Departamento Amazonas, Perú. Cienc. Amaz. 2020, 8, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E. Ecological Diversity and Its Measurement, 1st ed.; Springer Dordrecht: Bangor, ME, USA, 1988; ISBN 9789401573603. [Google Scholar]

- Somarriba, E. Diversidad Shannon. Agroforestería en las Américas 1999, 6, 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C.E. Métodos Para Medir La Biodiversidad, 1st ed.; CYTED/ORCYT-UNESCO/SEA: Zaragoza, Spain, 2001; ISBN 84-922495-2-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Suárez, B. Composición y Diversidad Del Banco de Semillas Germinable En Un Núcleo Ecológico Urbano. Pérez-Arbelaezia 2021, 22, 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Soto, S.; Gacitúa Arias, S.; Hernández, J.; Montenegro Rojas, J.; Jiménez, I.; Silva Aranguiz, E. Biodiversidad y Obras de Conservación de Agua y Suelo (OCAS) Forestadas Con Especies Vegetales En Ecosistemas Áridos de La Región de Coquimbo. Cienc. Investig. For. 2021, 27, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).