Abstract

This paper examines the socio-economic significance of forest visits and the collection of forest berries and mushrooms (FBMs) in the Czech Republic, emphasising their role in enhancing human well-being and contributing to regional economies. Over a 30-year period, data were collected on the quantities and economic values of FBMs, alongside the intensity of forest visits by the Czech population. This study incorporates a detailed analysis of time series data on FBM collection, exploring trends and fluctuations in the harvested quantities and their economic value. A Lorenz curve analysis reveals significant disparities in the distribution of economic benefits, with a small segment of the population accounting for the majority of the FBM-derived value. Additionally, the research investigates the impact of forest visitation on well-being at the regional level, highlighting the relationship between forest access, visitation intensity, and public health benefits. This study also examines visitors’ expectations, motivations, and perceptions regarding an ideal forest for visitation, providing recommendations for effective marketing strategies. Furthermore, the study explores the contribution of FBMs to net income across different regions, demonstrating substantial regional variation in their economic importance. Notably, the analysis shows that the value of FBMs represents approximately 37% of the net income generated by traditional forestry activities, underscoring its significant economic potential. The findings emphasise the potential of territorial marketing strategies to enhance well-being, particularly in economically disadvantaged regions, and advocate for sustainable forest management practices to protect these valuable resources and ensure equitable access to the benefits provided by forest ecosystems.

1. Introduction—Forest Ecosystems Services and Human Well-Being

Human well-being is a complex concept that encompasses various dimensions. According to Wright et al. [1], human well-being is defined as a state where human needs are met, individuals can pursue their goals, and they can enjoy a satisfactory quality of life. Similarly, Betley et al. [2] describe human well-being as a state of being with others and the environment, where their needs are met, and individuals can pursue their goals. Coulthard et al. [3] offer a stipulative definition of human well-being, focusing on meeting human needs, pursuing goals, and enjoying a satisfactory quality of life. Armitage et al. [4] define human well-being as an aggregation of basic material needs, health, security, social relations, and freedom of choice and actions. Breslow et al. [5] discuss global assessments of human well-being using quantitative indicators to measure various aspects of well-being. Forest ecosystems also provide a wide range of services and products that are essential for the well-being of both society and individuals.

The interlinks between the classification of ecosystem services and well-being were described in detail by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) [6], which categorises ecosystem services into four main types: provisioning, regulating, cultural, and supporting services. Furthermore, subsequent frameworks, such as The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity [7] and the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services [8], have proposed more refined classifications that emphasise different aspects of ecosystem services and their contributions to human well-being. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity [7] introduced a critical distinction between direct and indirect contributions of ecosystems to human well-being, highlighting the importance of recognising how ecosystem services underpin economic and social benefits. This framework underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of ecosystem services, particularly in how they relate to human welfare and economic valuation [9,10]. In contrast, the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services [8] simplifies the classification by focusing on three main categories: provisioning, regulating, and cultural services, while omitting the supporting services category due to concerns about double counting and the complexity of tracking these benefits [11,12]. This shift reflects a growing consensus among researchers that supporting services, while crucial, often overlap with other categories and complicate assessments of the ecosystem service value [13,14].

Our research covers both the direct and indirect TEEB framework categories. The collection of berries and mushrooms, which can enhance food security and generate income for local communities, can be assigned to the direct contributions. The health benefits associated with forest visitations are then included in the indirect contributions of ecosystems. The study indicates the relationship between forest access, visitation intensity, and public health benefits, reflecting TEEB’s focus on how ecosystems contribute to well-being beyond any direct economic measure.

Despite the critical role of these services, they have historically received less attention than timber, which has traditionally been the primary focus of European forest management. Understanding and documenting the full range of forest ecosystem services (FESs) is crucial for evaluating their contribution to human well-being and ensuring their sustainable use.

Forest berry and mushroom (FBM) picking in forests is both a foraging activity and a pastime that offers many benefits to human well-being. These activities provide essential nutritional resources and contribute significant psychological benefits by enhancing one’s mental health, reducing stress, and fostering a sense of connection to the natural environment [15,16]. Engaging in foraging serves as a cultural and recreational activity that plays a crucial role in sustaining traditional knowledge and practices, thereby contributing to community resilience and social cohesion [17].

Furthermore, foraging is closely linked to the broader concept of ecosystem services, highlighting the importance of conserving forest ecosystems not only for their biodiversity, but also for their role in supporting human health and well-being [18]. The experiential benefits of foraging underscore the relationship between human activities and the environment, emphasising the significance of sustainable practices to ensure the continued availability of these benefits [18]. Recognising the importance of foraging within the context of ecosystem services underscores the need for conservation efforts to protect forest ecosystems and ensure the continued provision of these valuable benefits to human societies. The act of foraging represents a direct interaction with nature, which is a fundamental component of ecosystem services that supports human life and one’s overall health and well-being. Direct use values, as part of the total economic value of forest ecosystem services, are derived from the FESs that humans directly utilise. These include both consumptive and non-consumptive uses, typically enjoyed by individuals who live in or visit these ecosystems. An environmental good or service generates direct value when it contributes directly to human utility as part of a forest ecosystem service [6].

The collection of FBMs is an integral part of regional foraging practices across Europe, including the Czech Republic. The practices are influenced by demographic and natural factors, local laws, and cultural values, causing regional differences in foraging FBM products. The presence of laws and regulations regarding the collection and trade of wild mushrooms in various European countries reflects different consumption behaviours and attitudes towards wild mushroom commerce [19]. For example, the economic and cultural value of forest mushrooms is evident in regions like Mazovia, Poland, where extreme levels of mycophilia are documented, showcasing the deep-rooted connection between local communities and wild edible fungi [20]. The transition from viewing forest resources as a means of economic survival to a source of recreation can be observed in rural Sweden, Ukraine, and northwest Russia, highlighting the evolving perspectives on the collection and utilisation of wild food and medicine in different European regions [21].

Forest visits and foraging are traditional recreational activities that significantly enhance human well-being. These activities often take place along marked trails, offering opportunities for recreation, aesthetic enjoyment, and a deeper connection with nature.

In the Czech Republic, the collection of FBMs is intricately linked to both the market and non-market ecosystem services of forests, contributing to the economic value as well as recreation and health. As highlighted by Sisak et al. [22], the collection of wild mushrooms and forest berries is influenced by demographic factors, with a large proportion of the Czech population participating in these activities, underscoring their importance as components of forest ecosystem services.

However, the well-being benefits of forest visits and foraging can vary not only over the years, but also by region, with disparities between local and non-local foragers and between different stakeholders, such as forest owners, trail managers, local communities, and tourism entrepreneurs. Tourism plays a crucial role in this dynamic, as many visitors, both domestic and international, engage in foraging and forest exploration, contributing to local economies through spending money on accommodations, dining, and other services. Understanding the specific contributions of forest visitation and foraging to regional economies is essential for developing strategies that maximise well-being while balancing the interests of all stakeholders. This calls for regionally tailored policies that consider the unique economic and social dynamics of each area. Additionally, sustainable management practices, supported by local regulations and education on responsible foraging, are necessary to protect these valuable resources from overuse.

This paper emphasises the potential of territorial marketing and associated services for further enhancing public well-being through forest visitation and the collection of FBM products in the Czech Republic, focusing on the following research questions:

- RQ1: The collection of FBMs has been monitored in the Czech Republic for 30 years. Have any trends emerged and have any patterns become visible during the observed period? What was the distribution of FBM product value in the last monitored years?

- RQ2: What is the importance of FBM collection compared to the value of timber in the last five years?

- RQ3: Does the research demonstrate regional disparities that would support the development of territorial marketing as a tool for increasing well-being?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Focus and Scope of the Research on FBMs in the Czech Republic

This research focuses on the socio-economic significance of forest berries and mushrooms and their influence on well-being across the entire Czech Republic (CZ), a Central European country with an area of 78,863 km2. Forestland constitutes 26,717 km2, or 33.9%, of the country’s total area. Under the Czech Forest Act, the collection of FBM products is legally permitted in 91% of forest areas, regardless of ownership, except in military forests and strictly protected nature reserves and zones within national parks [23]. The scope of this research includes the comprehensive analysis of several key FBM categories: the bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.), raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.), blackberry (Rubus fruticosus L.), elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.), cowberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.), and a generalised category for mushrooms (mainly the genera Boletus, Xerocomellus, Macrolepiota, Suillus, Leccinum, Cantharellus, Agaricus). This study does not specify individual mushroom species due to the variety of local names used for the same species. These particular berries and mushrooms were selected due to their high collection rates, reflecting their importance within the CZ.

The research, which has been systematically conducted since 1994, provides a unique 30-year time series that stands out in the global context for its consistency and depth. This long-term study has yielded valuable insights into the role of FBM products within the broader framework of forest ecosystem services in the Czech Republic.

The research encompasses the measurement of harvested quantities for both mushrooms and each berry type, recorded in kilogrammes. Additionally, the average market prices of these products were documented. The economic value of each type was determined by multiplying the harvested quantity by its corresponding market price in Czech Crowns (CZK). The average exchange rate in 2022 was 24.565 CZK/EUR and 23.36 CZK/USD.

Furthermore, the research also examines the intensity of forest attendance, which is intrinsically linked to recreation, relaxation, and overall public health. This aspect underscores the broader socio-economic benefits of FBM collection, as forest visits contribute not only to the direct economic value of these products, but also significantly enhance public well-being. By capturing the dual impact of forest use—both economic and health-related—this research provides a more holistic understanding of the value that forest ecosystems bring to society.

2.2. Survey Organisation

The data collection process for this research was conducted annually from 1994 to 2023, following a consistent and methodologically rigorous approach. Each year, the data were gathered in November and December after the mushroom and forest fruit collection season had concluded. This timing remained unchanged to ensure that the data collected would be directly comparable year-on-year. A fundamental set of questions, introduced in 1994, serves as the backbone of the survey, providing a stable foundation for the longitudinal analysis, which is listed in Appendix A. This core questionnaire was supplemented periodically to address emerging research interests, such as medical herb collection in 2023 and game meat consumption in 2002. The survey’s design was carefully constructed to allow for a broad exploration of related topics while maintaining the integrity of the core data.

The survey administration consistently employed face-to-face (F2F) interviews, which have been proven to yield higher response rates and more accurate data. A representative sample of at least 1000 respondents was selected each year through a quota sampling method, ensuring an adequate representation across gender, age, education, size of residence, and geographic region. The face-to-face method enables interviewers to collect nuanced responses, reducing the likelihood of misinterpretation or incomplete answers. Additionally, this method facilitates the administration of more complex questions and provides opportunities for clarification during the interview, further enhancing the data reliability.

To maintain high standards of data quality, the survey adheres to the guidelines set forth by the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research (ESOMAR) [24]. As part of these standards, 20% of all the interviews are monitored, with selected portions of the conversations being recorded for quality assurance purposes. Furthermore, telephone follow-ups are conducted to verify the accuracy of the responses, particularly for high-variance or extreme values. This dual verification process helps ensure the integrity and reliability of the collected data. Interviewers undergo regular training to minimise errors and ensure the consistency of the data collection process. These training sessions emphasise standardisation in the question administration and the handling of outlier responses, further contributing to the overall consistency of the dataset.

Data control is a central aspect of this research, with consistency checks performed during and after the data collection. A horizontal data analysis is conducted to ensure the internal consistency within the dataset. For example, the relationship between the intensity of forest visits and the quantity of collected mushrooms or berries is examined each year. In addition, the respondents’ reported data, such as the prices of forest fruits, are cross-verified with external data sources, including market prices from forest fruit collection centres. This triangulation of data sources helps to identify and address any inconsistencies, ensuring that the dataset remains robust and reliable over time.

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of visitors’ expectations, motivations, and perceptions regarding an ideal forest for visitation, the study’s findings were supplemented with data from extensive research conducted in 2018. This research involved a representative sample of 1519 respondents from the Czech Republic, aged 15 to 75, and was carried out in cooperation with the Ministry of Agriculture. The sample was carefully selected to represent the population based on gender, age, education, region, and size of residence. The data were collected using the Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) method, with interviews conducted during the period of 24 May to 4 June 2018, using a quota sampling method. Notably, the results of this research have not yet been published.

For the year 2023, the set of questions of the standard survey was further expanded to include a question about visitors’ feelings after visiting the forest.

2.3. Methods

First, the data on mushroom and forest berry collections from 1994 to 2023 were analysed as a time series to identify key patterns and long-term trends. Although parts of the aggregated results related to the mushroom and berry collection have been published annually to inform the state forest policy and support research by various national institutions, the complete 30-year time series of aggregated data on the estimated total annual collection of FBM products has never been published, despite its unique value, even at a European level. This continuous data collection allowed us to compile a graph and categorise the collected FBM amounts into two main groups: mushrooms and forest berries.

Second, to minimise the impact of outdated influences and factors and to achieve higher accuracy, a five-year period from 2019 to 2023 was selected for a more detailed analysis of the current data. This period provided a sufficient number of respondents (5096, see Table 1) for an in-depth examination in the subsequent steps. All the prices and values for this period were calculated using 2022 prices based on the price index reflecting the inflation rate published by [25].

Table 1.

The number of respondents from 2019 to 2023.

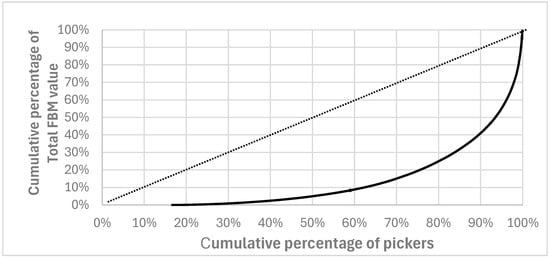

Third, the total value of mushrooms and forest berries, based on the collected volumes and relevant prices obtained from 5096 respondents between 2019 and 2023, was analysed using the Lorenz curve to assess the degree of inequality in the distribution of the collected value among mushroom and berry pickers. Inflation coefficients, which significantly impacted the later years, were considered in this assessment, and the value of the FBMs was adjusted to reflect their price in 2022. Traditionally, the Lorenz curve [26] represents the distribution of income or wealth within a population by plotting the cumulative percentage of the total income or wealth against the cumulative percentage of the population, starting with the poorest.

The Lorenz curve is a graphical representation of inequality, where perfect equality would be represented by a straight diagonal line (the line of equality). In contrast, the actual distribution typically forms a curve below this line. The more the Lorenz curve deviates from the diagonal, the greater the inequality in the distribution. For example, in the context of mushrooms and berries, if only a small percentage of foragers collect a large portion of the total value, the curve would bow significantly away from the line of equality, indicating high inequality. This tool allows for the clear visualisation of disparities in the economic value collected by different individuals and is particularly useful for understanding how resources like mushrooms and berries are distributed among harvesters.

Fourth, to assess the economic significance of collecting forest berries and mushrooms within the broader context of forestry’s contribution to society and the economy, the value, volume, and price of these collected products were compared with those of harvested wood and the net income generated by the forestry sector during the period from 2019 to 2022. The data for this comparison were sourced from the National Statistical Office [27]. To ensure consistency and comparability, all the relevant figures, including the prices and values, were adjusted to the 2022 price level using the official inflation coefficient. The four-year period from 2019 to 2022 was selected due to the unavailability of comprehensive official data for the entire forest sector for the year 2023.

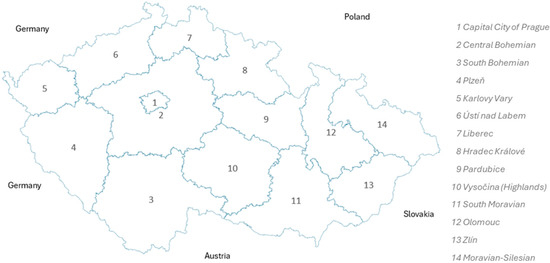

Fifth, a more detailed exploration was conducted to examine how forest visitation and the volume of collected forest fruits contribute to the well-being of the region’s inhabitants. The dataset includes responses from 5096 individuals, enabling relevant conclusions at the regional level. This analysis compares the value of the collected FBMs with the per capita income and other factors, such as the intensity of forest attendance. A list of regions [28] and a map of those regions can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The geographical structure of the regions in the Czech Republic.

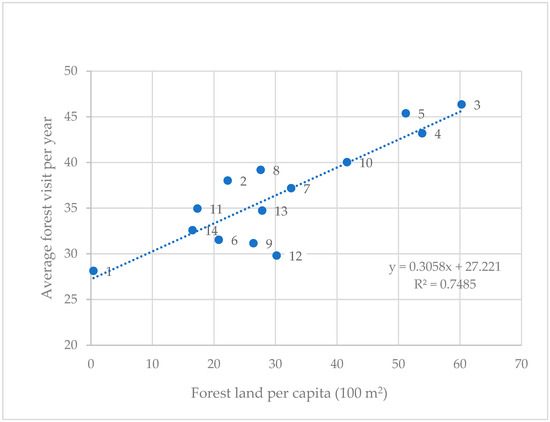

To examine the relationship between the forest land per capita and the average forest visits per year, a linear regression analysis was conducted, with forest land per capita as the independent variable and visit frequency as the dependent variable. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the strength and direction of this association [29]. In the linear regression model, the slope indicates the change in the visit frequency per unit increase in the forest land per capita. The R-squared value was used to assess the model’s explanatory power, indicating the proportion of variance in the visit frequency explained by the forest land per capita [30].

Sixth, unlike the economic value of forest berries and mushrooms (FBMs), assessing the “economic” value of forest visits—whether as a standalone activity or in connection with FBM collection—on visitors’ well-being is complex and varies by each individual. To address this, in 2023, a standardised questionnaire (see Appendix A) was updated to include the question “How do you feel after visiting the forest (the same, better, worse)?” The analysis of these responses was incorporated as evidence of the impact of the forest visits on an individual level. To evaluate whether visiting a forest positively influences an individual’s perceptions, a Chi-square goodness-of-fit test was conducted; see McHugh [31]. The respondents were categorised based on how they felt after visiting the forest (“Feel Worse”, “Feel Better”, and “Feel About the Same”), with the corresponding frequencies for each category. The null hypothesis assumed no difference in perception, meaning the individuals were equally likely to feel worse, better, or the same after a forest visit. The observed frequencies from the survey data were compared to the expected frequencies under a uniform distribution (i.e., each perception type would have equal representation if visiting the forest had no effect).

3. Results

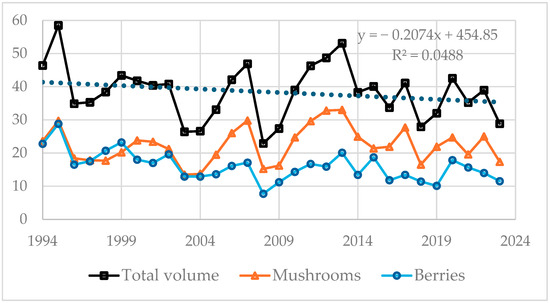

The analysis of the total volume of FBMs collected in the Czech Republic highlights a stable central tendency in collection over the unique 30-year time series. Although the estimated harvested quantities oscillate significantly between 25 and 60 million kilogrammes annually, the long-term central tendency remains almost constant, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The total volume of FBMs collected in the CZ (in millions of kg).

The trend line described by the equation y = −0.2074x + 454.85 indicates a very slight negative slope, suggesting a minor decrease in the total volume collected over the 30-year period. However, this decrease is not significant, and the low R2 value of 0.0488 indicates that the trend line does not adequately explain the variance in the data. This suggests that the year-to-year fluctuations are more strongly influenced by other factors rather than by time alone. As shown in [22,32], the fluctuations are influenced by a combination of socio-economic factors (such as unemployment rates and income levels), weather-related variables (including temperature and precipitation), occasional natural disturbances (like bark beetle outbreaks), lifestyle changes (such as domestic or international holidays), and potential statistical errors. Therefore, the analysis confirms that external factors, rather than time, are the primary drivers of the observed annual fluctuations in the collection volumes.

As shown in Figure 3, this distribution closely aligns with Pareto’s principle, where 80% of the respondents account for just 25% of the total value, while the remaining 20% captures 75% of the total value. The concentration curve analysis (see the detailed values in Table 2) further emphasises this disparity, with 95.51% of the respondents contributing to 60.27% of the total value, leaving the remaining 4.49% of the respondents to capture 39.73% of the total value.

Figure 3.

A Lorenz curve applied to the value of FBM collection during the period 2019–2023.

Table 2.

Classification of the respondents based on forest visitation and the collection of forest berries and mushrooms in the Czech Republic (2019–2023).

Table 3 compare the data on the collection of FBM products with selected indicators related to the wood production function of forests. The comparative analysis of the economic significance of collecting FBMs relative to traditional forestry outputs revealed significant insights. The adjusted data, standardised to the 2022 price level using the official inflation coefficient, provided a precise evaluation across the selected period of 2019 to 2022.

Table 3.

Comparison of the FBM and timber values FBM and timber values per ha in the period 2019–2022.

During this period, the total value of FBMs represents approximately 24.04% (28,957/120,442) of the total value of roundwood, as shown in Table 3. When compared with the net income from forestry, the value of the FBMs accounts for 37% (28,957/78,457), highlighting the considerable economic potential of FBM products relative to the traditional wood-based net income. The data are discussed in more detail in the discussion section.

As mentioned in the methods chapter, for a detailed analysis of the impact of forest visits and FBM collection on the regional level, see the calculated information in Table 4.

Table 4.

Basic characteristics of the Czech regions. (Average annual values based on the period 2019–2022.)

Table 4 provides a snapshot of the Czech Republic’s regions, focusing on the forest cover and its relationship with the population density, welfare economic indicators, and land use. Regions like Liberec and Vysočina stand out with a high forest cover (45% and 31%, respectively) and low population density per hectare of forest. In contrast, Prague, with only 11% forest cover, shows a high population density relative to its limited forest area, highlighting the strain of urbanisation on natural resources.

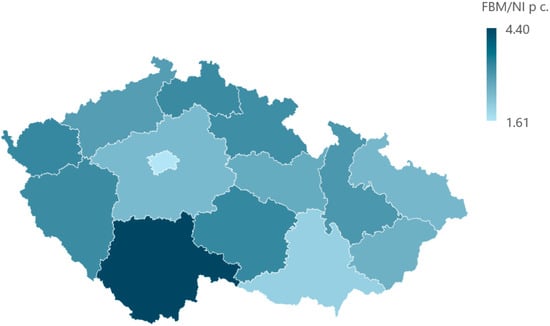

The map illustrates the value of FBMs in each region as a percentage of the net income during the considered period. As shown in Figure 4, the average contribution of forest visits in terms of the FBM value is less than 0.5% of the net average per capita income. However, this contribution varies significantly depending on both the region and the type of collector—for the top 4%, it is much higher. In regions with lower per capita income, the FBM value can represent as much as 10% of the net income.

Figure 4.

Contribution of FBMs to the net income per capita across the Czech regions (‰).

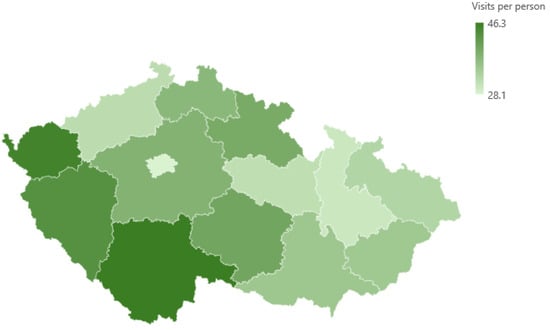

Furthermore, it is important to note that we have not yet considered the non-economic benefits of forests and forest visits that contribute to the well-being of the region’s inhabitants. The quantitative analysis of the forest visitation data produced the map shown in Figure 5 and revealed the relationship illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Average per year intensity of the forest visits per capita across the Czech regions (2019–2023).

Figure 6.

Relationship between the forest land per capita and the average intensity of the forest visits across the regions.

Figure 5 compares the average annual intensity of forest visits across the Czech regions. As shown in Figure 6, there is a strong relationship between the reported average annual intensity of forest visits and the forest area per capita in each region during the analysed period from 2019 to 2023. The linear regression equation y = 0.3058x + 27.221 indicates that, for each additional 100 m2 of forest land per capita, the average number of forest visits per year increases by approximately 0.306 visits. The model yielded an R2 value of 0.748, showing that 74.8% of the variance in the forest visit intensity is explained by the forest area per capita, with a correlation coefficient of 0.865. This strong association highlights the significant role of forest availability in influencing the public’s forest visit frequency.

However, a bit of an outlier value associated with region number 12, corresponding to the Olomouc region, stands out. This region includes a large military training area, where some forested sections are not accessible to the public. This restricted access likely reduces the potential intensity of forest visits, thereby deviating slightly from the trend observed in other regions.

A deeper qualitative insight into the expectations and individual satisfaction of the respondents with their forest visits can be gained from the research related to the preferences for an ideal forest, with the results summarised in Table 5.

Table 5.

Which forests do you prefer? (2018, 1519 respondents.)

Based on the results in Table 5, the respondents place high value on forests that allow foraging activities, such as mushroom and fruit picking, and those that support wildlife through feeding stations. This indicates a preference for forests that offer direct benefits to visitors and demonstrate care for wildlife. Many respondents also appreciate the existence of inaccessible areas within forests for undisturbed wildlife, reflecting strong support for conservation efforts and natural habitat preservation.

While relaxation areas are appreciated, they are moderately valued compared to other factors, aligning with the recreational use of forests as peaceful retreats. Opinions are divided on forests with large predators, with safety concerns making this a polarising issue. Cleanliness, including the management of debris, is a concern, but is less prioritised.

An important aspect of well-being, beyond the individual’s sense of comfort, is the overall feeling of psychological well-being and health. This is why, as noted in the methodology section, the 2023 survey included a question regarding the emotions elicited by a visit to the forest. The results of this question are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Individual perception after visiting the forest (2023, 1000 respondents).

Table 6 reveals that a significant majority, 650 out of 896 respondents (72.5%), reported feeling better after visiting the forest. This finding underscores the generally positive influence of forest visits on well-being. In contrast, only ten respondents (1.12%) reported feeling worse after their visit.

To further investigate, a Chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the association between the frequency of the forest visits and the individuals’ reported feelings afterward. The respondents were categorised into two groups: those who felt “Worse or the Same” and those who felt “Better”, across four levels of visit frequency.

The test indicated a statistically significant association between the visit frequency and the reported feelings, χ2(3, N = 896) = 18.24 with p = 0.00039, which is well below the conventional significance level of 0.05. This outcome confirms a statistically significant association between the frequency of forest visits and the likelihood of feeling better as opposed to feeling worse or the same.

When focusing on the respondents who reported negative feelings after a forest visit, a closer examination reveals several contributing factors:

- Health-related reasons for feeling worse: Those who reported feeling worse often cited specific physical ailments, such as knee pain, general health issues, and conditions like allergies.

- Psychological and situational factors: Psychological discomfort also played a role in the negative experiences, with some respondents mentioning that they “don’t feel good about the overall situation”. Fatigue, described as being “tired”, was another common reason. Additionally, limited mobility, as indicated by comments like “I need someone to take me there”, also influenced their perception of the forest visits.

4. Discussion

Historically, the economic valuation of forests has centred around wood products, primarily due to established market mechanisms and their predictable income generation for forest owners. However, this paradigm was significantly challenged during the bark beetle calamity in Central Europe [33], which saw the doubling of the harvested wood volume, leading to a sharp decline in wood prices [34] and increased costs. The cumulative loss for forest owners in CZ due to the bark beetle infestation was estimated at approximately 97 billion CZK [35]. This crisis underscores the necessity of exploring alternative forest products, such as forest berries and mushrooms, which provide not only significant economic value, but also substantial contributions to human well-being, particularly in specific regions and under certain conditions.

Table 3 underscores the economic significance of FBMs when compared to the values and incomes generated by the entire forestry sector. The significant increase in logging to 30 million m3 in 2019 and 2020 is noteworthy [36], driven by the bark beetle outbreak, which starkly contrasts with the long-term average of approximately 16 million m3. This surge in wood harvest was accompanied by a substantial rise in costs and negative externalities associated with excessive logging—factors that were not fully accounted for in the traditional economic evaluations.

In contrast, the collection of forest berries and mushrooms offers a range of positive effects and contributions to societal well-being, particularly through the recreational and health benefits of forest visits [37,38]. These benefits became especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic when forest visitation reached record levels [39,40]. The act of visiting forests and gathering forest products significantly contributed to alleviating the psychological impacts of the pandemic and improving the physical condition of the forest visitors, underscoring the importance of these activities beyond their direct economic value.

As shown in Figure 3 and further analysed in Table 2, a small segment of the population (4.5%) accounts for 39.7% of the total value derived from FBMs, revealing a pronounced uneven distribution in the use of these resources. This finding suggests a “free-rider” effect [41,42] in forest ecosystem services, where a minority disproportionately benefits from the shared natural resources. This disparity raises critical questions about equity and access, indicating that, while foraging is a widespread activity, the economic benefits—and, consequently, the well-being derived from these activities—are concentrated among a few.

Moreover, the data revealed that approximately 20.5% of the population does not engage in foraging, with half of this group not visiting forests at all. Notably, 53% of those who do not visit forests (comprising 560 individuals out of the total sample of 5096) are over the age of 60. These findings highlight the significance of social dynamics and accessibility issues in the management and policymaking of forest ecosystem services. Addressing these barriers is crucial for ensuring inclusive participation and equitable access to the benefits provided by forest resources, thereby enhancing the overall well-being of the population.

The well-being associated with forest activities, including foraging for FBMs, is not evenly distributed across regions. As illustrated in Figure 4, the contribution of FBMs to the overall income per capita varies significantly. Prague, with its high income per capita and greater distance from FBM collection areas, contrasts sharply with Southern Bohemia, where the high forest density, lower population density, and relatively lower income per capita make FBMs a more critical component of the local economy. Central Bohemia, although geographically closer to Prague, experiences heavy visitation, reducing the likelihood of large FBM harvests. These regional differences underscore the need for tailored strategies that consider local contexts and the varying economic and well-being contributions of FBMs.

To address the regional imbalances and uneven distribution of benefits, adopting territorial marketing strategies aligned with synchromarketing principles is essential. Vikhoreva and Jakobson [43] highlight that effective territorial marketing not only focuses on a region’s intrinsic qualities, but also on how these qualities are communicated to potential visitors. This is particularly critical in eco-tourism, where real-time data can emphasise seasonal opportunities, such as foraging and drawing visitors, while distributing economic benefits more equitably across regions.

Synchromarketing, a key element of territorial marketing, adjusts marketing efforts to meet fluctuating demand. This approach helps ensure that ecosystem services, like mushroom and berry foraging, are managed sustainably by promoting lesser-visited areas and redistributing the visitor pressure. Promoting less-visited areas and enhancing them with additional services can more equitably distribute the economic value and well-being benefits while alleviating the pressure on overburdened regions [44]. A cohesive marketing strategy that leverages a region’s unique characteristics can elevate both traditional and non-wood forest products, transforming these offerings into significant economic opportunities and enhancing the well-being, particularly in regions with expansive forest areas.

As Holloway [45] notes, real-time data help businesses better forecast demand and personalise their marketing, optimising the timing and location of eco-tourism activities. Real-time engagement, discussed by Buhalis and Sinarta [46], allows destinations to provide personalised, timely experiences, enhancing the competitiveness and visitor satisfaction.

In Finland, Jokamiehenoikeus and apps like ExcursionMap.fi offer real-time data on foraging, ensuring both sustainable practices and enriching visitor experiences [47]. Similarly, Sweden’s Allemansrätten and digital tools like Naturkartan integrate weather data to guide visitors and promote eco-tourism events such as the Kantarellfest [48].

Territorial marketing in forestry can transform regional offerings by coordinating recreational services, local markets, and community-led activities. By leveraging technologies, these strategies not only enhance visitor experiences, but also promote the sustainable use of forest ecosystems [49,50].

The well-being benefits of forest visits are well documented, particularly for regular visitors who predominantly report positive or neutral health outcomes. The majority of the respondents (72.5%) reported feeling better after visiting the forest, as shown in Table 6. This positive influence on well-being highlights the broader social benefits of forest visits. However, a small group reported negative outcomes, often due to pre-existing health conditions or situational discomforts. The results here correspond with [51]. Public health strategies should focus on making forest environments more accessible and comfortable for individuals with physical limitations or chronic health conditions. Improving access and amenities and implementing targeted health interventions for specific age groups, particularly the elderly, can enhance their well-being during forest visits.

Understanding visitor expectations and their behaviour is crucial for developing targeted marketing strategies that direct people to less frequented areas, thereby balancing the visitor distribution and protecting local ecosystems. Surveys offer valuable insights into the frequency and circumstances of the forest visits, which can inform territorial marketing strategies aimed at promoting sustainable forest visitation and enhancing well-being.

A notable example of how mycotourism has been successfully integrated into forest management and local economies is found in Spain. Since the turn of the millennium, mycotourism has been developing within the framework of the Spanish mycological programme, which began in Castile. Buntgen et al. [52] emphasise the interconnected social, economic, political, and scientific importance of mycotourism. In Spain, an exceptional alliance of mycologists, foresters, gastronomists, farmers, and politicians was formed to create a broad programme that unites municipal, national, and even pan-European initiatives to boost public interest in mushroom foraging and its related activities [53].

A specific example is the company Del Monte de Tabuyo, which owns a restaurant, a small shop, and an online store specialising in the sale of wild mushrooms. The mushrooms are supplied by a local cooperative that has obtained all the necessary certifications and permits for mushroom harvesting, including the documentation of their origin. Customers of the Del Monte de Tabuyo restaurant consist of 45% from the local region and 55% from other regions and abroad. This model exemplifies how mycotourism can drive the local economic development while enhancing the public well-being by connecting people with nature through sustainable practices [54].

Based on the presented results, several key measures can be recommended to enhance the overall forest experience, with a particular focus on well-being. First, promoting and enhancing foraging opportunities is crucial, given the recreational and practical benefits of foraging, which directly contribute to well-being. Specific forest areas should be developed and promoted where foraging is safe and sustainable, complemented by educational programmes that teach visitors about local flora, safe foraging practices, and ecological impact.

In addition to foraging, developing wildlife observation areas is important, as the public values opportunities to observe animals in their natural habitats. Establishing dedicated observation points, particularly near feeding stations, with a minimal impact on the animals and supplemented by educational signage, can enhance visitor experiences and contribute to their well-being.

Promoting conservation zones is also essential for preserving rare species and maintaining natural habitats, which are widely appreciated by the public and contribute to overall well-being. Conservation areas within forests should be clearly marked, with human access restricted to protect wildlife, while guided tours can educate visitors on the importance of these efforts.

Finally, enhancing relaxation and recreational facilities is a priority for improving well-being. Installing and maintaining comfortable relaxation spots, such as benches, picnic areas, and scenic viewpoints, can make forests more accessible to a broader audience, particularly older adults and families seeking a peaceful retreat. These enhancements can significantly contribute to the well-being of forest visitors by providing opportunities for rest, reflection, and connection with nature.

The need for forest owners to adapt or develop new business models is increasingly evident, particularly in response to global changes. Kajanus et al. [55,56] emphasise that these models should not only focus on new products or services, but also consider other components of the business model. For example, [56] discusses an expanded canvas business model used in Finland for a paid mobile application that helps urban residents locate optimal forest harvesting sites, reflecting the increased interest in wild food. This model captures essential business aspects and informs marketing strategies, demonstrating how innovation can drive economic opportunities in forestry and enhance well-being.

In a related context, Purwestri et al. [57] discuss the socio-economic value of non-wood forest products, including mushrooms and berries, in the Czech Republic. Their findings reveal that these products are essential for recreational activities and have significant socio-economic implications for local communities. Furthermore, the study by Tampakis et al. highlights that traditional forest management can significantly enhance nature-based tourism landscapes, which, in turn, can lead to increased recreational opportunities and employment in local areas [58]. Such findings suggest that increased forest visits and berry collection can directly correlate with higher overnight stays in nearby accommodations, as tourists seek to experience the natural beauty and resources of forested areas. Additionally, the research by Butler et al. [59] explores the cultural and recreational significance of foraging for mushrooms and berries. The study highlights how these activities foster a connection to nature and contribute to community identity, particularly in the context of environmental changes such as forest fires. The research by Herrero et al. [60] explores the productivity of mushrooms in Mediterranean Pinus pinaster forests, emphasising how forest management practices can influence mushroom yields. The study suggests that moderate thinning can enhance the mushroom productivity, which could attract more visitors to the forests for collection purposes. Kyere-Boateng et al. [61] further illustrate the socio-economic role of non-wood forest products (NWFPs), including mushrooms and berries, in Europe. Their research indicates that these products serve as additional household income sources, particularly for poorer households that rely on low-value forest resources. In a similar direction, Enescu et al. [62] highlight the ecological and economic importance of non-timber forest products in Romania, noting that wild berries and mushrooms are among the most collected NWFPs. The study indicates that the harvesting of these products can have both positive and negative ecological impacts, depending on the scale of collection. The detailed and comprehensive study by Lovrić et al. [63] provides a quantitative overview of non-wood forest products in Europe, emphasising that mushrooms and berries are integral to forest recreation and rural income.

Rametsteiner et al. [64] further analysed innovation processes and systems in Central European forestry, highlighting the role of institutional frameworks, public and private entities, and their interactions in fostering innovation. Jarský [65] notes that the longevity and multifunctionality of forestry make it one of the most conservative sectors in the Czech Republic, with significant barriers to innovation. Šišák [66] identifies these barriers, including economic factors and a slow legal environment, which hinder the adoption of new practices. However, the size of the forest assets also plays a critical role in innovation frequency, as larger assets provide a stronger financial base and management stability [67].

Cooperation among smaller forest owners is recommended by Dobšinská et al. [68], who advocate for “cluster grouping”, as a means of enhancing strategic positions and fostering innovation. This inter-sectoral cooperation is crucial for developing new forestry products and services, as emphasised by Niskanen et al. [69], who highlight the importance of cross-industry collaboration, the better integration of research, and effective information dissemination.

In conclusion, the future viability of forest ownership hinges on embracing innovation, adopting new business models, and strengthening inter-sectoral cooperation. As Hansen [70] and Weiss et al. [71] argue, the forestry sector must innovate and adapt to remain competitive, particularly in the face of global changes and evolving market dynamics. The integration of FBMs into broader forest management strategies, supported by targeted marketing and innovation, offers a promising path forward for sustainable forestry and enhanced well-being.

5. Conclusions

RQ1: The collection of FBMs has been monitored in the Czech Republic for 30 years. Have any trends emerged and are there any patterns visible during the observed period? What was the distribution of the FBM product value in the last monitored years?

Although the quantity of collected FBMs fluctuates annually due to varying environmental conditions, the overall long-term trend in FBM collection remains stable. This consistency highlights the resilience and sustained importance of FBM collection to local communities. Moreover, an analysis of the distribution of the total value of the FBMs collected over the past five years demonstrates a strong alignment with Pareto’s principle: 80% of the respondents contribute to only 25% of the total value. This suggests that a small segment of collectors is responsible for the majority of the FBM contributions, pointing to potential disparities in the participation and collection intensity across the population.

RQ2: What is the importance of FBM collection compared to the value of timber in the last five years?

FBM collection plays a significant role in the economic valuation of forest resources, especially when compared to the traditionally dominant timber industry. Over the past five years, the value derived from FBMs has accounted for an average of 37% of the Total Forestry Net Income from timber production. This highlights that, while timber remains the primary economic driver in forestry, FBM collection represents a potential source of income. Its consistent contribution emphasises the broader economic value of non-timber forest products and the need to consider FBM collection as an integral component of forest resource management. The relatively high percentage also indicates the importance of diversifying forest income streams to ensure the sustainability of both timber and non-timber resources.

RQ3: Does this research demonstrate regional disparities that would support the development of territorial marketing as a tool for increasing well-being?

This research reveals significant regional disparities in FBM collection and forest visitation across the Czech Republic, which presents opportunities for leveraging territorial marketing strategies to enhance local well-being. Regions with higher FBM collection rates and more frequent forest visits could be targeted for promoting these activities as part of local development initiatives. Such strategies can be particularly beneficial for economically disadvantaged areas, where FBM collection could provide both economic and social benefits. As mentioned in the previous section, territorial marketing, when integrated with synchromarketing principles, offers a strategic approach to managing the demand for forest resources, promoting sustainable collection practices, and distributing economic benefits more equitably.

The analysis reveals a strong relationship between regular forest visits and positive long-term health perceptions, particularly among frequent visitors (see Table 6). Foraging activities in forests contribute holistically to human well-being by offering physical, psychological, cultural, and recreational benefits. The data highlight the significant impact of FMB products on public attitudes toward forests, forestry, and forest ownership. These influences shape the perceptions of foresters and their roles, with important implications for public support of forest management and its related activities. In the socio-historical context in the CR, the right to free access to forests and the collection of forest products plays a pivotal role in shaping the public opinion and support for forestry.

While forest visits provide clear personal benefits, it is crucial to implement strategies that extend these advantages to the regions where these activities occur. The growing shift in rural regions from production to consumption, emphasising recreational land use over traditional agriculture and forestry, offers an opportunity to revitalise rural economies through targeted marketing and sustainable forest management.

In light of these changes, the close monitoring of forest crop production and collection is essential. Establishing a dedicated unit within the central authority to address these issues with a focus on forest policies, legislation, and resource management is a step worth serious consideration.

As the importance of ecosystem services continues to grow, particularly in relation to human well-being, developing effective methods to evaluate and support these benefits in the Czech Republic becomes increasingly critical. One promising approach involves implementing direct payments to forest owners for activities that promote ecosystem services. This issue is also a focal point of ongoing research in the Czech Republic, aiming to establish effective strategies to enhance ecosystem protection and growth, ultimately contributing to the sustainability and resilience of natural resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.R. and V.J.; methodology, M.R. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N. and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic through the National Agency for Agricultural Research of the Czech Republic (NAZV), project No. QK23020008.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alan Harvey Cook for his careful proofreading and valuable insights, which contributed to the clarity and quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- Question 1 How often do you visit a forest?

- Not at all

- Once or twice a year

- Once a month

- Once a week

- More often

- Question 2 Which listed forest products do you collect, and in what amount annually? (take your whole household into account).

| Forest Product | Collect | Amount |

| Mushrooms | 1 | |

| Bilberries | 2 | |

| Raspberries | 3 | |

| Blackberries | 4 | |

| Cowberries | 5 | |

| Elderberries | 6 |

- Question 3 Can you specify (if you are informed) what is the average market price (CZK/kg) of the following forest products?

| Forest Product | Average Price (CZK/kg) |

| Mushrooms | |

| Bilberries | |

| Raspberries | |

| Blackberries | |

| Cowberries | |

| Elderberries |

References

- Wright, K. Constructing human wellbeing across spatial boundaries: Negotiating meanings in transnational migration. Glob. Networks 2011, 12, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betley, E.C.; Sigouin, A.; Pascua, P.; Cheng, S.H.; MacDonald, K.I.; Arengo, F.; Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y.; Caillon, S.; Isaac, M.E.; Jupiter, S.D.; et al. Assessing human well-being constructs with environmental and equity aspects: A review of the landscape. People Nat. 2021, 5, 1756–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, S.; Johnson, D.; McGregor, J.A. Poverty, sustainability and human wellbeing: A social wellbeing approach to the global fisheries crisis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D.; Béné, C.; Charles, A.T.; Johnson, D.; Allison, E.H. The Interplay of Well-being and Resilience in Applying a Social-Ecological Perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, S.J.; Sojka, B.; Barnea, R.; Basurto, X.; Carothers, C.; Charnley, S.; Coulthard, S.; Dolšak, N.; Donatuto, J.; García-Quijano, C.; et al. Conceptualizing and operationalizing human wellbeing for ecosystem assessment and management. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 66, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhdev, P.; Wittmer, H.; Schröter-Schlaack, C.; Nesshöver, C.; Bishop, B.; ten Brink, P.; Gundimeda, H.; Kumar, P.; Simmons, B. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Mainstreaming the Economics of Nature: A Synthesis of the Approach, Conclusions and Recommendations of TEEB; UNEP: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency Structure of CICES. Available online: https://cices.eu/cices-structure/ (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Janssen, A.B.G.; Hilt, S.; Kosten, S.; de Klein, J.J.M.; Paerl, H.W.; Van de Waal, D.B. Shifting states, shifting services: Linking regime shifts to changes in ecosystem services of shallow lakes. Freshw. Biol. 2021, 66, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierry de Ville d’Avray, L.; Ami, D.; Chenuil, A.; David, R.; Féral, J.P. Application of the ecosystem service concept at a small-scale: The cases of coralligenous habitats in the North-western Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadykalo, A.N.; Kelly, L.A.; Berberi, A.; Reid, J.L.; Scott Findlay, C. Research effort devoted to regulating and supporting ecosystem services by environmental scientists and economists. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.A.; Schulz, C. Do ecosystem services provide an added value compared to existing forest planning approaches in Central Europe? Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin Frisk, E.; Volchko, Y.; Taromi Sandström, O.; Söderqvist, T.; Ericsson, L.O.; Mossmark, F.; Lindhe, A.; Blom, G.; Lång, L.O.; Carlsson, C.; et al. The geosystem services concept—What is it and can it support subsurface planning? Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 58, 101493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.P.; Sousa, A.I.; Alves, F.L.; Lillebø, A.I. Ecosystem services provided by a complex coastal region: Challenges of classification and mapping. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karjalainen, E.; Sarjala, T.; Raitio, H. Promoting human health through forests: Overview and major challenges. Environ. Heal. Prev. Med. 2009, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.M.; Mills, J.G.; Breed, M.F. Walking Ecosystems in Microbiome-Inspired Green Infrastructure: An Ecological Perspective on Enhancing Personal and Planetary Health. Challenges 2018, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Gaibor, I. Socioecological Dynamics and Forest-Dependent Communities’ Wellbeing: The Case of Yasuní National Park, Ecuador. Land 2023, 12, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doimo, I.; Masiero, M.; Gatto, P. Forest and Wellbeing: Bridging Medical and Forest Research for Effective Forest-Based Initiatives. Forests 2020, 11, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peintner, U.; Schwarz, S.; Mešić, A.; Moreau, P.A.; Moreno, G.; Saviuc, P. Mycophilic or Mycophobic? Legislation and Guidelines on Wild Mushroom Commerce Reveal Different Consumption Behaviour in European Countries. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowski, M.A.; Pietras, M.; Łuczaj, Ł. Extreme levels of mycophilia documented in Mazovia, a region of Poland. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryamets, N.N.; Elbakidze, M.M.; Ceuterick, M.M.; Angelstam, P.P.; Axelsson, R.R. From economic survival to recreation: Contemporary uses of wild food and medicine in rural Sweden, Ukraine and NW Russia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šišák, L.; Riedl, M.; Dudík, R. Non-market non-timber forest products in the Czech Republic-Their socio-economic effects and trends in forest land use. Land. Use Policy 2016, 50, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MZe. Zpráva o Stavu Lesa a Lesního Hospodářství. 2022. Available online: https://mze.gov.cz/public/portal/mze/publikace/Zprava-o-stavu-lesa-a-lesniho-hospodarstvi-CR/zprava-o-stavu-lesa-a-lesniho-hospodarstvi-2022-strucna-verze (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- ESOMAR. The ICC/ESOMAR International Code. Available online: https://esomar.org/code-and-guidelines/icc-esomar-code (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- CSO. Inflation 2000–2023. Available online: https://csu.gov.cz/docs/107516/50f82cf1-a2f4-7c5d-f999-d97082215071/Inflace_2000_2023.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Gastwirth, J.L. A General Definition of the Lorenz Curve. Econometrica 1971, 39, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSO. Economic Accounts for Forestry and Logging, Years 2017–2022. Available online: https://csu.gov.cz/docs/107508/dbefc0e9-dfd4-b55f-f9a4-61a456e7efc0/100004243k31.xlsx?version=1.0 (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- CSO. Comparison of Regions in the Czech Republic—2023. Available online: https://csu.gov.cz/produkty/comparison-of-regions-in-the-czech-republic-2023 (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agresti, A. Statistical Methods for the Social Sciences; Pearson: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M.L. The Chi-square test of independence. Biochem. Med. 2013, 23, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, M.; Jarský, V.; Zahradník, D.; Palátová, P.; Dudík, R.; Meňházová, J.; Šišák, L. Analysis of Significant Factors Influencing the Amount of Collected Forest Berries in the Czech Republic. Forests 2020, 11, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlásny, T.; König, L.; Krokene, P.; Lindner, M.; Montagné-Huck, C.; Müller, J.; Qin, H.; Raffa, K.F.; Schelhaas, M.J.; Svoboda, M.; et al. Bark Beetle Outbreaks in Europe: State of Knowledge and Ways Forward for Management. Curr. For. Rep. 2021, 7, 138–165. [Google Scholar]

- Hlaváčková, P.; Banaś, J.; Utnik-Banaś, K. Intervention analysis of COVID-19 pandemic impact on timber price in selected markets. Policy Econ. 2024, 159, 103123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CFTT Press Releases CZECH FOREST Think Tank | Czech Forest. Available online: http://www.czechforest.cz/tiskove-zpravy (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- CSO. Forestry|Statistics. Available online: https://csu.gov.cz/forestry?pocet=10&start=0&podskupiny=101&razeni=-datumVydani (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Šodková, M.; Purwestri, R.C.; Riedl, M.; Jarský, V.; Hájek, M. Drivers and Frequency of Forest Visits: Results of a National Survey in the Czech Republic. Forests 2020, 11, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, A.C.; Salak, B.; Hegetschweiler, K.T.; Bauer, N.; Hunziker, M. How the COVID-19 pandemic changed forest visits in Switzerland: Is there a back to normal? Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2024, 249, 105126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, J.; Giessen, L.; Winkel, G. COVID-19-induced visitor boom reveals the importance of forests as critical infrastructure. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarský, V.; Palátová, P.; Riedl, M.; Zahradník, D.; Rinn, R.; Hochmalová, M. Forest Attendance in the Times of COVID-19—A Case Study on the Example of the Czech Republic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihani, N.J.; Hart, T. Free-riders promote free-riding in a real-world setting. Oikos 2010, 119, 1391–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, N.L. Motivation losses in small groups: A social dilemma analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikhoreva, M.; Jakobson, A. Socio-economic conditions as a factor of revealing cities’ marketing potential. Stud. Ind. Geogr. Comm. Pol. Geogr. Soc. 2020, 34, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, F.; Seeler, S. Demarketing Strategy As a Tool to Mitigate Overtourism—An Illusion? In Overtourism as Destination Risk (Tourism Security-Safety and Post Conflict Destinations); Sharma, A., Hassan, A., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2021; pp. 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, S. Exploring the Impact of Real-Time Supply Chain Information on Marketing Decisions: Insights from Service Industries. Preprints 2024, 2024061500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Sinarta, Y. Real-time co-creation and nowness service: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excursionmap.fi. Is a Map Service for Nature Lovers | Metsähallitus. Available online: https://www.metsa.fi/en/lands-and-waters/state-owned-areas/excursionmap-fi/ (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Who Does What in Outdoor Recreations in Sweden? Available online: https://www.naturvardsverket.se/en/topics/outdoor-recreation/who-does-what-in-outdoor-recreations-in-sweden/ (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Pettenella, D.; Corradini, G.; Da Re, R.; Lovrić, M.; Vidale, E. NWFPs in Europe–consumption, markets and marketing tools. In Non-Wood Forest Products in Europe: Seeing the Forest around the Trees; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2019; pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pettenella, D.; Secco, L.; Maso, D. NWFP&S Marketing: Lessons Learned and New Development Paths from Case Studies in Some European Countries. Small-Scale For. 2007, 6, 373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Lamatungga, K.E.; Pichlerová, M.; Halamová, J.; Kanovský, M.; Tamatam, D.; Ježová, D.; Pichler, V. Forests serve vulnerable groups in times of crises: Improved mental health of older adults by individual forest walking during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2024, 7, 1287266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntgen, U.; Latorre, J.; Egli, S.; Martinez-Peña, F. Socio-economic, scientific, and political benefits of mycotourism. Ecosphere 2017, 8, e01870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- micoTURISMO | Micocyl. Available online: http://micocyl.es/micoturismo (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Del Monte de Tabuyo | Restaurante y Venta de Conservas Artesanales Naturales-Especialidad en Conservas de Frambuesa, Vegetales y Setas. Available online: http://www.delmontedetabuyo.com/ (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Kajanus, M.; Iire, A.; Eskelinen, T.; Heinonen, M.; Hansen, E. Business model design: New tools for business systems innovation. Scand. J. Res. 2014, 29, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajanus, M.; Leban, V.; Glavonjić, P.; Krč, J.; Nedeljković, J.; Nonić, D.; Nybakk, E.; Posavec, S.; Riedl, M.; Teder, M.; et al. What can we learn from business models in the European forest sector: Exploring the key elements of new business model designs. Policy Econ. 2019, 99, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Purwestri, R.C.; Hájek, M.; Šodková, M.; Jarskỳ, V. How Are Wood and Non-Wood Forest Products Utilized in the Czech Republic? A Preliminary Assessment of a Nationwide Survey on the Bioeconomy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampakis, S.; Andrea, V.; Karanikola, P.; Pailas, I. The Growth of Mountain Tourism in a Traditional Forest Area of Greece. Forests 2019, 10, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.; Ångman, E.; Ode Sang, Å.; Sarlöv-Herlin, I.; Åkerskog, A.; Knez, I. “There will be mushrooms again”–Foraging, landscape and forest fire. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 33, 100358. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, C.; Berraondo, I.; Bravo, F.; Pando, V.; Ordóñez, C.; Olaizola, J.; Martín-Pinto, P.; de Rueda, J.A.O. Predicting Mushroom Productivity from Long-Term Field-Data Series in Mediterranean Pinus pinaster Ait. Forests in the Context of Climate Change. Forests 2019, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyere-Boateng, R.; Marek, M.V.; Huba, M. Assessing changes in ecosystem service provision in the Bia-Tano forest reserve for sustained carbon mitigation and non-timber forest products provision. Geogr. Cas. 2022, 74, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enescu, R.; Dincă, L.; Vasile, D. The main non-timber forest products from alba county. Curr. Trends Nat. Sci. 2022, 11, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovrić, M.; Da Re, R.; Vidale, E.; Prokofieva, I.; Wong, J.; Pettenella, D.; Verkerk, P.J.; Mavsar, R. Non-wood forest products in Europe–A quantitative overview. Policy Econ. 2020, 116, 102175. [Google Scholar]

- Rametsteiner, E.; Weiss, G. Innovation and innovation policy in forestry: Linking innovation process with systems models. Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarský, V. Analysis of the sectoral innovation system for forestry of the Czech Republic. Does it even exist? Policy Econ. 2015, 59, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Šišák, L. Potenciál inovací v lesním hospodářství versus tradice a právní prostředí v České republice. In Stav a Perspektivy Inovací v Lesním Hospodářství: Sborník Referátů ze Semináře s Mezinárodní Účastí; FLD ČZU v Praze: Prague, Czech Republic, 2007; pp. 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Šálka, J.; Longauer, R.; Lacko, M. The effects of property transformation on forestry entrepreneurship and innovation in the context of Slovakia. Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobsinska, Z.; Sarvasova, Z.; Salka, J. Changes of innovation behaviour in Slovak forestry. USV Ann. Econ. Public. Adm. 2010, 10, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Niskanen, A.; Slee, B.; Ollonqvist, P.; Pettenella, D.; Bouriaud, L.; Rametsteiner, E. Entrepreneurship in the Forest Sector in Europe; University of Eastern Finland: Joensuu, Finland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E.N. The Role of Innovation in the Forest Products Industry. J. For. 2010, 108, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G.; Pettenella, D.; Ollonqvist, P.; Slee, B. Innovation in Forestry: Territorial and Value Chain Relationships; CABI: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).