1. Introduction

Plant pests are a threat to biodiversity, food security, and the economy. Human activities play an important role in favoring the emergence and spread of pests, for example via the increased long-distance trade of plants and plant products, changes in cultivation practices, the cultivation of new plant species, and tourism. Forests are also at risk, and losses due to the introduction of pests in forests have been highlighted in many review papers (e.g., [

1,

2,

3]). The challenges posed by the introduction of plant pests (which have greatly increased in the last century) have triggered the establishment of cooperative mechanisms to protect agriculture, biodiversity, and the economy from pests. These mechanisms include the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC), an international treaty to protect plant health adopted in 1951. The purpose of the IPPC is to coordinate joint actions to prevent the spread and introduction of pests of plants and plant products and to promote appropriate measures for their control. The Convention includes provisions for the establishment of Regional Plant Protection Organizations (RPPOs), which are inter-governmental organizations functioning on a regional level as coordinating bodies for National Plant Protection Organizations (NPPOs), i.e., the official services that are responsible for plant protection in countries. RPPOs coordinate and participate in activities in their regions to promote and achieve the objectives of the IPPC.

The RPPO for the European, Mediterranean, and Central Asian regions is the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO). It was created in 1951, and today, 52 countries are members of the Organization. Some of the key aims of the Organization are the following:

Develop an international strategy against the introduction and spread of pests (including invasive alien plants) that damage cultivated and wild plants in agricultural and natural ecosystems.

Encourage harmonization of phytosanitary regulations and all other areas of official plant protection action.

Provide documentation and information services on plant protection.

In order to achieve these aims, different activities are conducted. Because EPPO’s work is focused on pests presenting a risk to the Euro-Mediterranean and Central Asian regions, activities are conducted as follows:

Identify pests that represent a risk before they reach the region or spread within it.

Recommend phytosanitary measures to prevent the entry or spread of such pests.

Develop guidance on how pests can be detected, identified, and controlled.

Since 1999, the EPPO has maintained an Alert List (

https://www.eppo.int/ACTIVITIES/plant_quarantine/alert_list (accessed on 26 June 2023)) and provided information on pests possibly presenting a risk to EPPO member countries and achieve early warning. It is also used by EPPO to select candidates, which are then submitted to a Pest Risk Analysis (PRA). EPPO has approved standards for PRA which are consistent with the IPPC Standards (ISPM 2 and ISPM 11

https://www.ippc.int/en/core-activities/standards-setting/ispms/ (accessed on 26 June 2023)). The aim of PRA is to decide whether pests should be regulated as quarantine pests and propose risk management options [

4]. A number of forestry pests are recommended for regulation by EPPO, e.g.,

Agrilus planipennis (Emerald ash borer, A2 List),

Anoplophora glabripennis (Asian long-horned beetle, A2 List),

Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Pinewood nematode, A2 List)), and

Phytophthora ramorum (the causal agent of sudden oak death, A2 List)).

Once a pest has been identified as presenting a risk for the EPPO region, recommendations are developed to assist NPPOs in conducting their activities, including:

Guidance on how and when to perform inspections at import and export and for surveillance of their territory.

Guidance on how to detect and identify pests may be developed.

Guidance on how to eradicate and control pests may also be developed to guide NPPOs in case an outbreak is detected.

Recommendations are approved by EPPO member countries and published as EPPO Standards, known in the IPPC context as “regional standards”.

Facilitating cooperation in research on pests is also one of the functions of EPPO. As research does not pertain only to NPPOs, Euphresco, a network now including 75 important actors involved in phytosanitary research (i.e., research funders, policymakers, and research implementing organizations), has been developed. This network coordinates phytosanitary research by mapping national programs, developing common research agendas, and organizing calls for topics and projects which can be supported by interested funding partners. Euphresco was initiated in 2006 through an EU funding program for the European Research Area Networks (“ERA-nets”). Since 2014, the network has been hosted by the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO), and since the decision of the EPPO Council in 2016, EPPO has provided through its main budget, dedicated funding for Euphresco. Research cooperation was one of the functions of EPPO set out in its founding convention in 1951. The goal of the network is to increase coordination of plant health research programming and support transnational collaboration. The benefits of this coordination are multiple and have been described in [

5,

6]. Many projects commissioned through the Euphresco network relate to diagnostic issues but also facilitate preparedness regarding pests (such as the project ‘Tree Borers: risk assessment, risk management and preparedness for emerald ash borer and bronze birch borer (PREPSYS)’ (

https://drop.euphresco.net/data/f4164235-1e51-4333-aabd-d89f341c43fd (accessed on 26 June 2023)). Participation in projects is possible through different mechanisms: in-kind contribution, alignment of existing research activities, and ad hoc funding from national funders that support the participation of their national scientists.

Why is diagnostics important?

Accurate and reliable detection and identification are essential in order to be able to take appropriate measures against a pest and thus avoid or reduce the economic, social, and environmental costs that it can cause. The main aim of this article is to present the diagnostic activities conducted by the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization and Euphresco. Some information is also presented on other initiatives in diagnostics.

2. EPPO Regional Program on Diagnostics

2.1. Pest-Specific Diagnostic Standards

The first initiatives for developing diagnostic protocols (=diagnostic standards) were taken by EPPO in 1998 with the establishment of a specific program on diagnostics. It was recognized that rapid and accurate identification is key to any action to be taken on an imported consignment or, in the case of an incursion in the region, that harmonization of diagnostic procedures is important to ensure safe movement of plants and plant products. The first diagnostic protocols were published in 2001 [

7], and, as of May 2023, more than 150 diagnostic standards had been approved. As the number of protocols to be developed in the different disciplines increased, the EPPO Secretariat suggested to its member countries that specific expertise was needed, and five Panels were established on different disciplines, including the Panel on Diagnostics in Entomology in 2010. Panels are composed of diagnostic experts nominated by the NPPOs of EPPO member countries. The composition of the EPPO Panels can be viewed on the EPPO Website (

https://www.eppo.int/ABOUT_EPPO/eppo_bodies (accessed on 26 June 2023)).

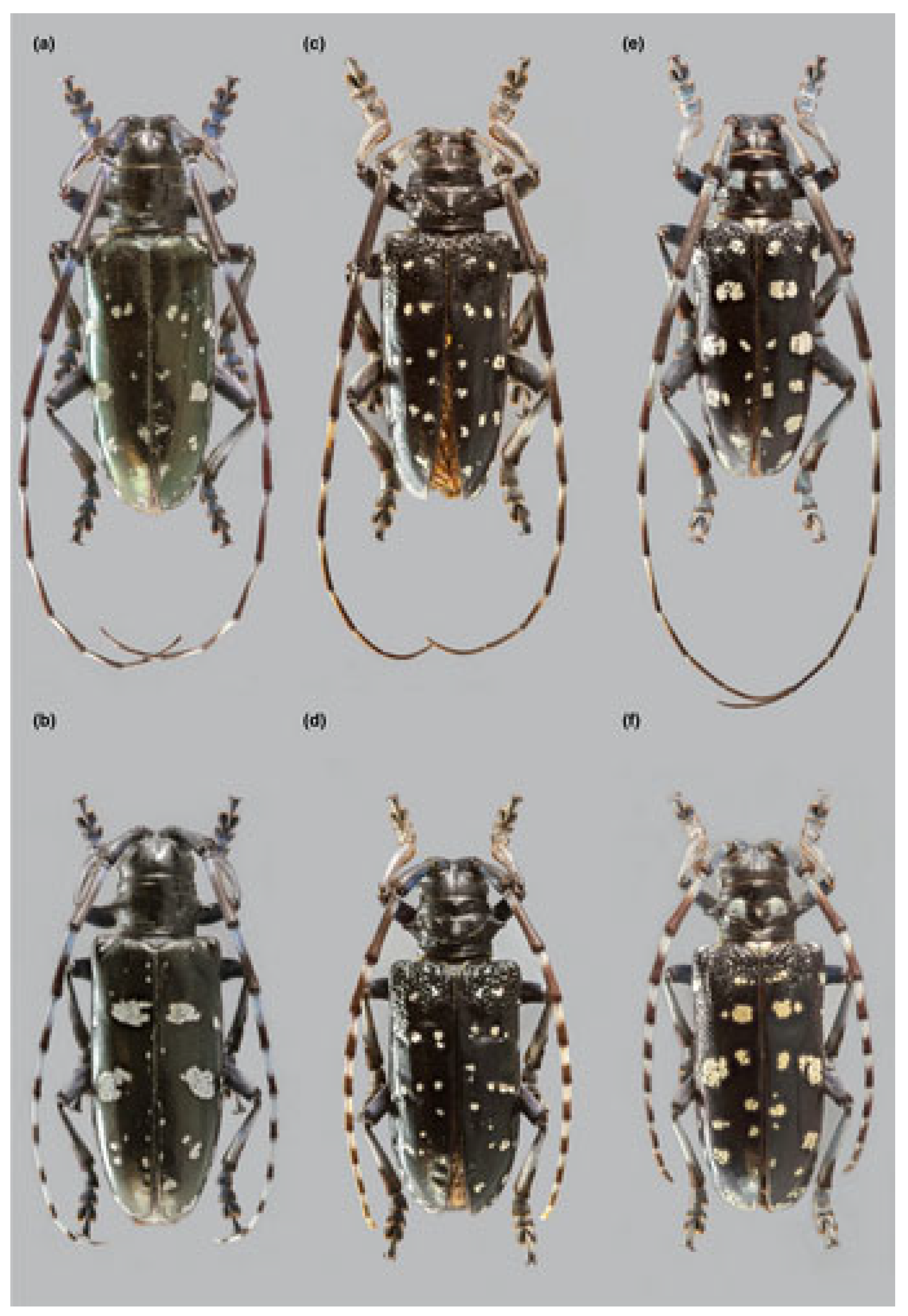

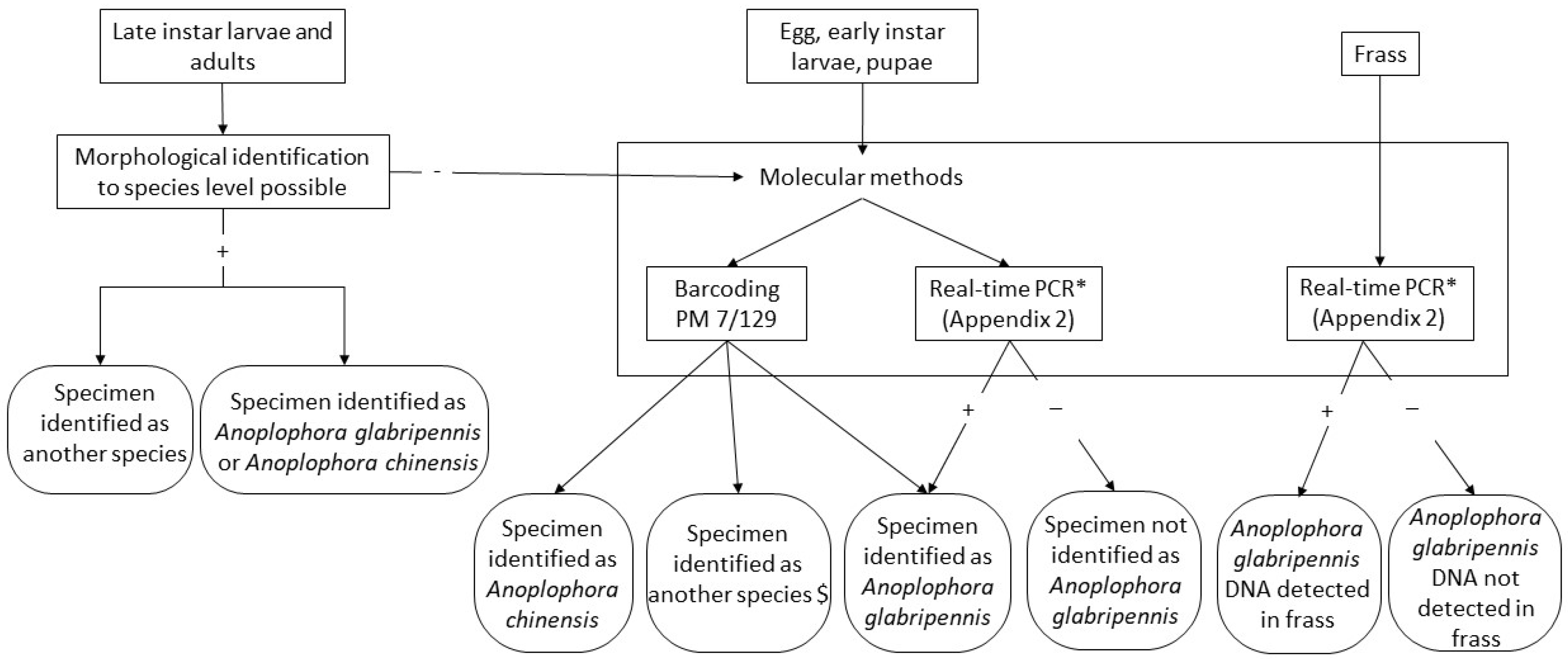

Diagnostic protocols provide the information necessary to detect and positively identify a particular pest. Each first draft is prepared by a team of experts with a lead author according to a common format. Although the lead author should preferably be a member of the Panel, other members of the drafting team do not have to be Panel members and can also be from outside the EPPO region. This is particularly valuable for protocols on pests which are not present in the EPPO region and for which expertise in the region is limited. Protocols for arthropods include detailed descriptions and keys for morphological identification, but nowadays molecular tests are also included. Diagnostic protocols are illustrated by figures to support their implementation (e.g.,

Figure 1), and when needed, flow diagrams presenting the diagnostic procedure are also included (e.g.,

Figure 2). Molecular tests included in EPPO diagnostic protocols are described in detail, and the most relevant performance characteristics of the tests are included, such as analytical sensitivity, analytical specificity, repeatability, and reproducibility. This information is important as many laboratories in the EPPO region are now required to be accredited for the tests they perform for official diagnostic activities. They need to demonstrate that they can perform the tests in accordance with the performance characteristics described. The number of molecular tests included in diagnostic protocols for arthropods has increased in the last decade, and experts are also asked to investigate if ‘quick tests’ that can be used on-site with portable equipment, such as those based on isothermal amplification, are available and can be included. Horizontal protocols related to a specific method are also developed by EPPO. For example, PM 7/129

DNA barcoding as an identification tool for a number of regulated pests [

8] describes tests that can be used for the identification of many pests and provides guidance on how to perform sequencing and data analysis.

When a first draft of a diagnostic protocol is considered ready by the drafting team, it is presented during a meeting of the relevant Diagnostic Panel, where it is critically reviewed. The drafting team will then revise the diagnostic protocol, taking into account the comments made by the Panel. A revised version of the protocol is then circulated again to the Panel, which decides if the protocol is ready to be sent for a formal consultation, during which all EPPO member countries have the opportunity to express their views.

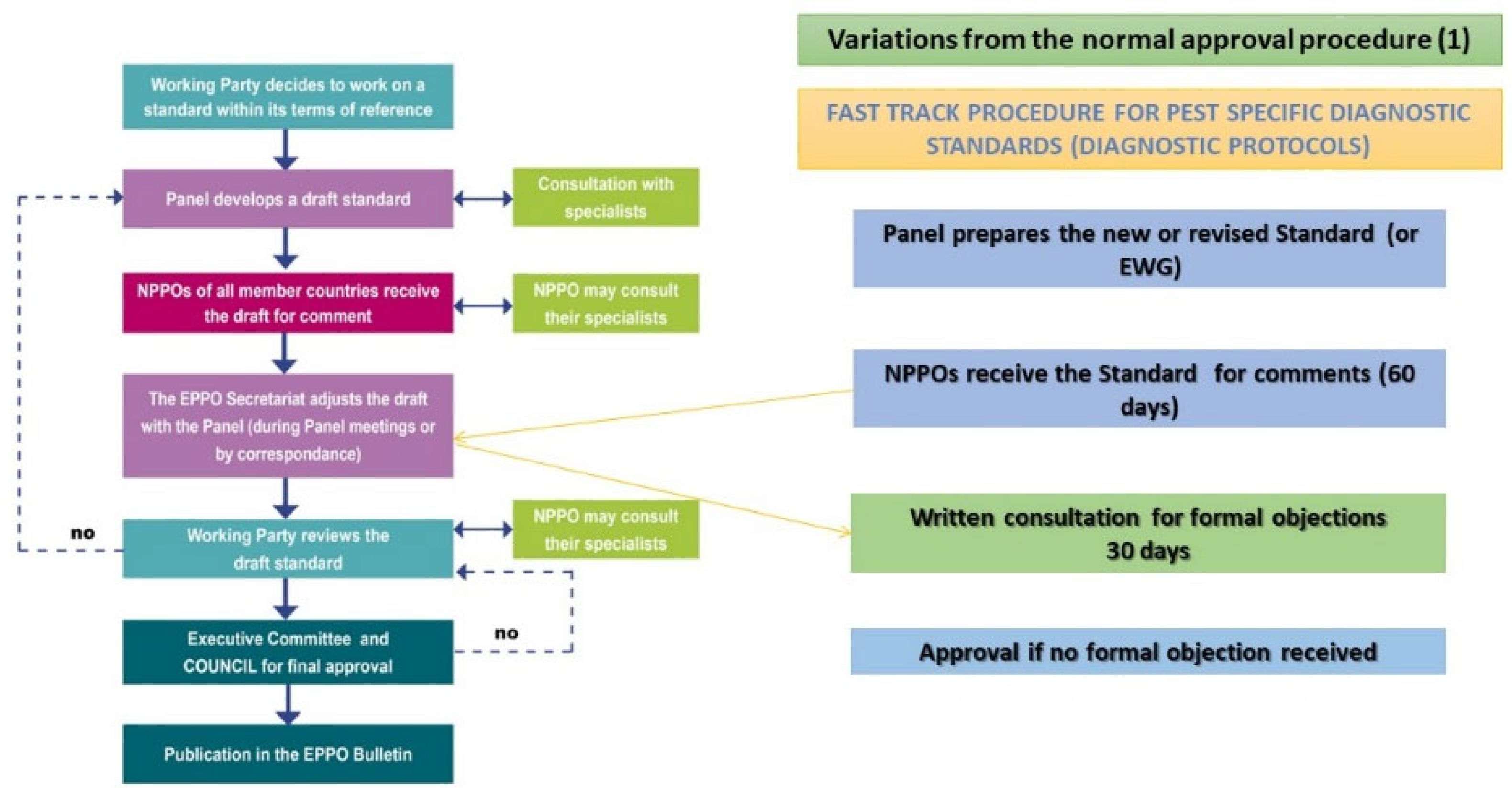

The approval procedure of EPPO diagnostic protocols is presented in

Figure 3. Pest-specific diagnostic protocols are approved following a variation from the normal approval procedure. More details are available in the ‘Procedure for preparation and approval of EPPO Standards’ [

9]. Comments received from EPPO member countries are reviewed by the drafting team, the Panel, and a revision is prepared. This revision is then sent for a last consultation, where the 52 EPPO member countries are given the possibility to present an objection if the modifications made after the first consultation are not acceptable.

If no objection is received during the last stage of consultation, the diagnostic protocol is approved and published in the EPPO Bulletin. All approved diagnostic standards can also be retrieved from the EPPO Website (

https://www.eppo.int/RESOURCES/eppo_standards/pm7_diagnostics, (accessed on 26 June 2023)) and via the EPPO Global database (

https://gd.eppo.int/standards/PM7/ (accessed on 26 June 2023)). As of May 2023, there were more than 150 diagnostic standards approved.

2.2. Standards on Accreditation and Quality Management for Plant Health Laboratories

In addition to pest-specific diagnostic protocols, EPPO is also developing Standards on horizontal issues such as accreditation and quality assurance.

Since 1999, there have been several discussions on the possibility that EPPO should assist national diagnostic laboratories in obtaining accreditation. It was concluded that EPPO could develop a quality assurance standard for diagnostic laboratories, but that accreditation can only be provided by an official (national) outside body. In order to support its members, EPPO has developed two diagnostic Standards regarding quality assurance and accreditation. The first Standard on quality assurance (PM 7/84,

Basic requirements for quality management in plant pest diagnosis laboratories) was approved in 2007 and was last revised in 2021. It includes the general quality management requirements needed to perform diagnostic tests for plant pests in a laboratory. The second Standard, PM 7/98 (

Specific requirements for laboratories preparing accreditation for a plant pest diagnostic activity), includes specific quality management requirements for laboratories preparing for accreditation, according to the ISO/IEC Standard 17025 General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories (references to relevant parts of the ISO/IEC Standard 17025 are included) [

10]. Such a Standard was considered particularly useful to promote a harmonized interpretation across the region (it has subsequently been revised four times as more experience was gained and due to the revision of ISO/IEC Standard 17025). In 2009, a joint communiqué was signed by EPPO and The European Co-operation for Accreditation (EA), stating that ‘

EA will recommend that assessors from Accreditation Bodies take note of EPPO documents when evaluating plant pest diagnostic laboratories’. A revised version of this communiqué was signed in October 2018. EA is the European network of nationally recognized accreditation bodies located in the European geographical area.

EPPO has also developed Standards on the organization of interlaboratory comparisons (PM 7/122) and on the production of biological reference material (PM 7/147).

2.3. Other EPPO Initiatives in the Field of Diagnostics

- a.

EPPO database on diagnostic expertise

In 2004, the EPPO Council stressed that the implementation of phytosanitary regulations for quarantine pests was jeopardized by decreasing knowledge in plant protection and made an official declaration (Plant Health Endangered, also known as the ‘Madeira declaration’). The Panel on Diagnostics proposed that an inventory is made of the available expertise in diagnostics in the region. A database on Diagnostic Expertise (

https://dc.eppo.int/ (accessed on 26 June 2023)) was then created to allow the identification of experts who could provide diagnosis of, e.g., regulated species or pests possibly presenting a risk to EPPO member countries (EPPO Alert List), or help in the identification of new species or those that are difficult to identify. Approximately 700 experts from more than 100 diagnostic laboratories in the EPPO region have provided details about the pests they can diagnose and the methods they use. The database also provides an inventory of validation data (as referred to in PM 7/98) for tests targeting the above-mentioned pests.

EPPO-Q-bank (

https://qbank.eppo.int/ (accessed on 26 June 2023) is composed of seven curated databases covering different disciplines (e.g., entomology and mycology). Each database comprises genetic sequences (e.g., barcodes) of quarantine pests and their lookalikes. Initiated as a Dutch project, it has been hosted by EPPO since 2019. The cornerstone of these databases is their curation by a team of scientists with taxonomic, phytosanitary, and diagnostic expertise from National Plant Protection Organizations and institutes with connections to relevant phytosanitary collections. Most strains, isolates, or specimens from which sequences are included in the EPPO-Q-bank databases were obtained from physical collections. EPPO-Q-bank databases also provide valuable information about these specimens, strains, or isolates, information about barcoding and sequencing methodologies, and tools to perform single- and multi-locus blast searches. As of May 2023, the EPPO-Q-bank databases include information on more than 2000 species, 9500 specimens, strains, or isolates, and 25,000 sequences.

EPPO regularly (co-) organize(s) workshops and conferences on diagnostics to enhance collaboration between laboratories and networking, share good practices, and tackle specific diagnostic issues. For example, workshops for the heads of plant pest diagnostic laboratories are regularly organized to discuss, at the management level, horizontal diagnostic topics such as quality assurance, accreditation under ISO 17025, and the proficiency of laboratories. Specific technical workshops have also been organized on various topics, such as the maintenance of collections and the use of high throughput sequencing for plant pest diagnostics. Finally, training courses are also organized, sometimes in the framework of specific projects (e.g., the Euphresco PRACTIBAR, a project on barcoding, and VALITEST, an EU-funded project on the validation of plant pest diagnostic tests). In 2022, The EPPO Secretariat and the IPPC Secretariat co-organized a dedicated session entitled ‘Plant pests diagnostic: its importance and its relation to food security’ during the first International Plant Health Conference (London 2022-09-21/23).

4. Euphresco Activities

Harmonization in standard setting is complicated by the diversity of tests used in different countries, which often have comparable performances and have been used for many years. This diversity explains why a consensus on International Standards is often only found on a minimum common basis. In order to enhance harmonization and adoption of common practice early on in laboratory activities, international collaboration and coordination of research that underlies official diagnostic activities have been promoted in recent years. Since 2006, Euphresco has supported the coordination of plant health research programming activities that support policymaking in the EU, facilitated the exchange of knowledge and capacity building on research matters, and allowed international collaboration between countries that share the same interests.

Starting as a network of several western European countries, Euphresco has now developed into a network of 75 organizations from more than 50 countries worldwide.

Diagnostics is an important activity in Euphresco research projects. More than 80 research projects (out of more than 120 projects commissioned through Euphresco so far) have a diagnostic component. Euphresco projects have allowed test development, the organization of test performance studies (TPS), and proficiency tests (PT). The projects are used to support capacity building, exchange of reference material, create better links between researchers and policymakers, and to engage with the end-users of research (e.g., farmers and nursery workers). As an example, the project ‘Developing and assessing surveillance methodologies for

Agrilus beetles’ (

https://drop.euphresco.net/data/68aca0f8-1b49-436a-8d7d-e0c5445119e3 (accessed on 26 June 2023)) allowed information to be gathered on existing surveillance protocols and for novel methods to be evaluated.

The success of Euphresco as a primarily European network for phytosanitary research coordination has set the groundwork for discussions on the development of initiative(s) to address the needs of other regions of the world and global phytosanitary research coordination. In 2019, during the Meeting of the Agricultural Chief Scientists of the G20 (MACS), the need ‘

to strengthen research collaboration to develop effective measures against transboundary pests and to participate in joint funding networks such as Euphresco’ [

13] was noted. In 2020, the article ‘Science diplomacy for plant health’ [

6], co-authored by experts from the IPPC, several RPPOs, NPPOs, research coordination networks, and research organizations, highlighted the need for ‘

a global network for phytosanitary research coordination that can shape research agendas across countries and accelerate the development of science to support regulatory phytosanitary decision makers’. In 2021, the IPPC Strategic Framework 2020–2030 [

11] was adopted at the 15th session of the CPM. Global phytosanitary research coordination is one of the development programs identified, and it is expected that by 2030 ‘

possibilities for establishing an international research collaborative structure have been explored and, if appropriate, the structure has been established’.

While Euphresco has been effective in Europe and has attracted non-European members, its current structure and operations limit the full engagement of non-European members; moreover, there are research areas that are underrepresented. Euphresco members are currently reflecting on how to clarify the role of Euphresco in the global plant health research context and how to adapt its structure and operations to better serve a wider and more diverse membership. It will hopefully result in a stronger network with a broader audience and a greater impact in terms of plant health research.

6. Conclusions

Activities on diagnostics have been and continue to be of prime importance for EPPO members and have been one of the main areas in which the Organization has made its mark in recent years, in its publications and on its website. A very valuable international resource has been created, and a basis has been laid for active cooperation between EPPO countries in the provision of diagnostic services. Euphresco research activities provide scientific evidence to support EPPO Standard setting.

High-throughput sequencing (HTS), also known as Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) or deep sequencing, is one of the most significant advances in molecular diagnostics since the advent of the PCR method in the early 1980s. It is a good example of a new technology which is now being adopted by diagnostic laboratories. Compared to more traditional methods, HTS can potentially detect the nucleic acids of any organism present in a sample without any a priori knowledge of the sample’s phytosanitary status [

15,

16], which opens new possibilities and opportunities in routine diagnostics [

17]. A recommendation on ‘Preparing the use of high throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies as a diagnostic tool for phytosanitary purposes’ was adopted by the CPM in 2019 [

18]. This recommendation encourages the development of best-practice operational guidelines covering results and quality control measures for HTS that ‘ensure HTS data outputs are robust and accurate, have biological significance in a phytosanitary context, and are implemented in a harmonized way, test validation and quality assurance’ [

19]. In addition, it highlights the need to validate HTS tests. In line with this recommendation, an EPPO Standard was developed based on the outcome of the EU-funded VALITEST project [

19] and describes specific elements to take into consideration for the use of HTS tests in laboratories [

20].

Remote Sensing is another technology that could radically change the way NPPOs work. Currently, inspections are mainly targeted, for example, at commodities arriving at ports, airports, or places of production. General surveillance of forests and natural areas is also performed but requires a lot of resources, both from the NPPOs and from other bodies and stakeholders involved in such activities. Remote sensing, by satellites, manned aircraft, or drones, facilitates the work of image acquisition, which is carried out in real time, and the processing of information on both a small and large scale. Remote sensing has the potential to guide surveillance activities on the ground without having to visit a site in person, and analysis of specific spectral bands can, in some cases, detect stress potentially associated with the presence of a disease before plant symptoms are visible to the naked eye [

21]. This allows inspections to be better targeted. Although remote sensing has already demonstrated its potential to strengthen surveillance for important pests such as the bacterium

Xylella fastidiosa, there have been few operational applications to date in the field of plant health. Barriers to implementation have been identified [

22], and transdisciplinary collaboration will be needed in the next few years to foster the operational use of remote sensing to support plant health surveillance activities.

Although new technologies offer new possibilities, it is essential that classic expertise (including taxonomy) is maintained and new expertise developed, that bridges between disciplines are built or strengthened, and that data and information are shared and made available for use and re-use. International organizations will have an essential role to play in ensuring collaboration and harmonization and that resources are used in the most efficient way possible to protect forest health worldwide.