The Need to Establish a Social and Economic Database of Private Forest Owners: The Case of Lithuania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Concept of Socio-Economic and Legal Data of Private Forest Owners

2.2. Experience and Benefits of Socio-Economic Data Monitoring of Private Forest Owners for Sustainable Forest Development

3. Methods

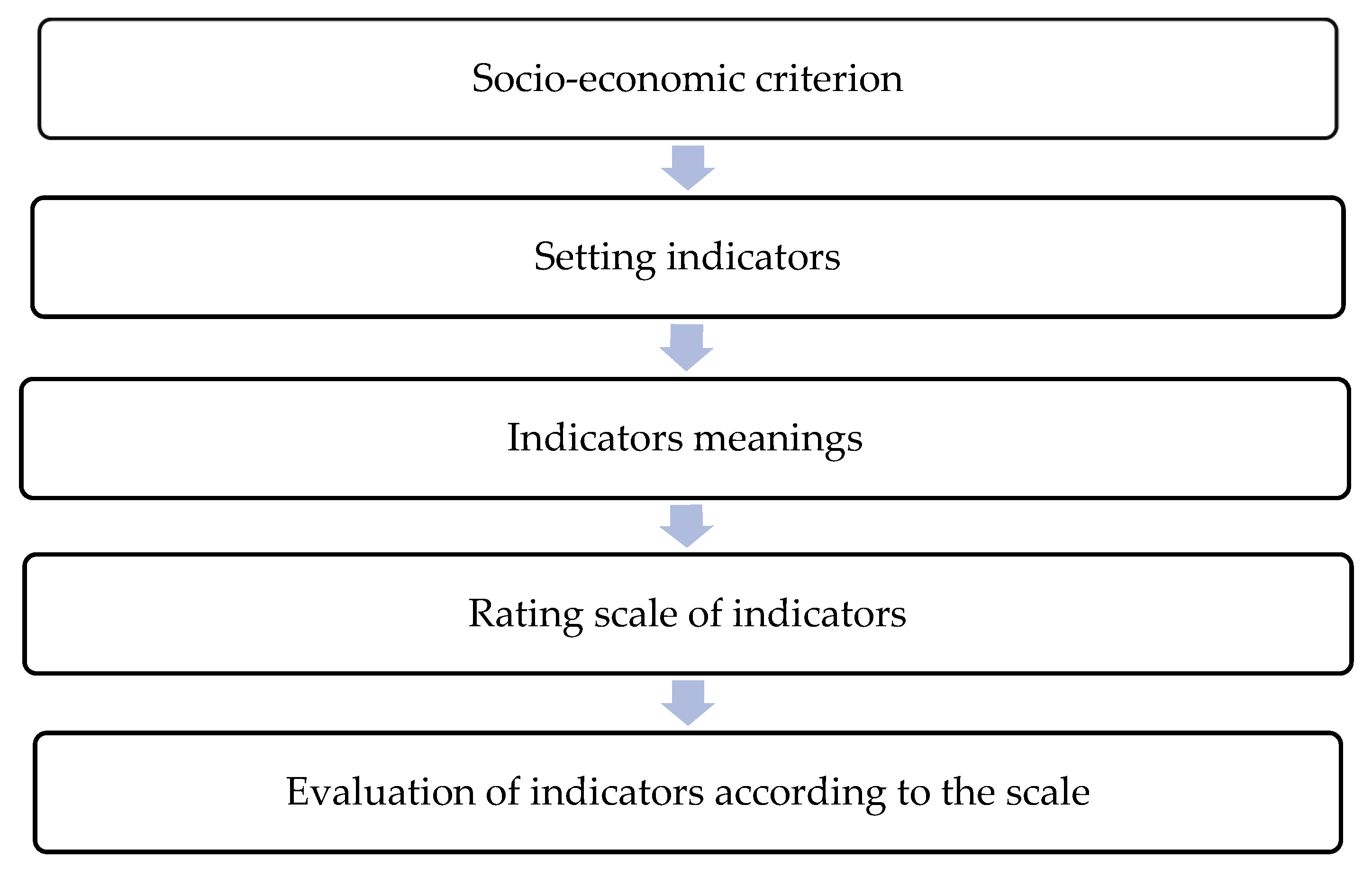

3.1. Methodologic Structure

3.2. Sample Group

- At least university-level education.

- At least 5 years of work experience in the field of forestry, forest economy or forest policy formation.

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

“Would reveal the real problems that exist in private forestry” (I1). “It is not clear how the owner disposes of his forestry property” (I3). “It would be clear why there are unequal farming conditions, what bureaucratic problems exist in private forestry” (I5). “It would become clear why forest owners are reluctant to manage and abandon their forests” (I9). “The reasons why the owners do not manage their forest property would be revealed” (I10).

“Provide suggestions on how to make the activities of private forest owners more efficient” (I1). “Would improve the regulation of this sector” (I2). “Predict the provisions of the Lithuanian forest strategy” (I4). “Understanding the real situation will help form forest policy” I5 “Improve policy, legislation, awareness and training” (I6). “Changes in private forestry could be managed” (I8).

“Provide recommendations necessary to carry out forestry activities” (I1). “Accurate data, forecasting trend” (I2). “To organize education of private forest owners” (I3). “Owners would be focused on ways and means to increase forestry efficiency” (I7). “To plan what kind of training would be needed for forest owners” (I9). “To plan and manage changes in the private forest estate” (I8). “Improve consulting services and their system for forest owners” (I10).

“The owners will think about where the data will go, they will think about the penalties” (I1). “Weak activity of forest owners “(I2).”The reluctance of forest owners to share data “(I3). “Owners are afraid that the data can be used by third parties carrying out unfair transactions and speculations” (I4). “Reluctance to cooperate, insufficient data coverage” I5.”Reluctance to disclose financial and sensitive social information” (I6). “Owners’ interests” (I7). “I don’t want interference in my private life” (I8). “People will be reluctant to answer; the data provided will be inaccurate” (I9). “Fear of the owners of violation of their personal rights, violations of personal data protection” (I10).

“Distrust of the owner” (I1). “Communication barrier for objective information” (I6). “Lack of resources for database establishment, availability of information” (I2). “Objectivity of selection, accessibility of owners” (I6). “Badly designed questionnaires that will not reveal the necessary information” (I7). “Formal approach–only to organize the process, lack of funding and expertise, fragmentation” (I8). “Intervention of state institutions, especially of the political sector” (I9).

“Unreliability of obtained results” (I1). “Information availability problems, compatibility of various databases” (I2). “Problems of incorrect and fragmented information” (I8).” “possible violations of the human right to personal data protection and ensuring a high level of personal data protection” (I10).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sotirov, M.; Deuff, P. United in diversity? Typology, objectives and socio-economic characteristics of public and private forest owners in Europe. Concepts Methods Find. For. Ownersh. Res. Eur. 2015, 25–36, hal-02602234. [Google Scholar]

- Brukas, V.; Sallnäs, O. Forest management plan as a policy instrument: Carrot, stick or sermon? Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A.; Dandy, N. Private landowners’ approaches to planting and managing forests in the UK: What’s the evidence? Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner Davis, M.L.E.; Fly, J.M. Do You Hear What I Hear: Better Understanding How Forest Management Is Conceptualized and Practiced by Private Forest Landowners. J. For. 2010, 108, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Sotirov, M. Understanding policy change across multiple levels of governance: The case of the European Union’s biodiversity conservation policy. Ambio 2013, 50, 1988–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Laakkonen, A.; Hujala, T.; Pykäläinen, J. Integrating intangible resources enables creating new types of forest services-developing forest leasing value network in Finland. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 99, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, K.; Bolte, A.; Haeler, E.; Haltia, E.; Jandl, R.; Juutinen, A.; Kulhlmey, K.; Mäkipää, R.; Lidestav, G.; Rosenkranz, L.; et al. Forest values and application of different management activities among small-scale forest owners in five EU countries. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 146, 102881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häyrinen, L.; Mattila, O.; Berghäll, S.; Närhi, M.; Toppinen, A. Exploring the future use of forests: Perceptions from non-industrial private forest owners in Finland. Scand. J. For. Res. 2017, 32, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, M.A.; Généreux-Tremblay, A.; Gilbert, D.; Gélinas, N. Comparing the profiles, objectives and behaviors of new and longstanding non-industrial private forest owners in Quebec, Canada. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 78, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilainen, A.; Lähdesmäki, M. Passive or Independent? An Empirical Study of Different Reasons Behind Private Forest Owners: Passiveness in Finland. In Proceedings of the IUFRO 3.08.00 Small-Scale Forestry 2019 Conference Proceedings, Duluth, MN, USA, 8–10 July 2019; University of Minnesota: Duluth, MN, USA, 2019; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; UNECE. Guidelines for the Development of a Criteria and Indicator Set for Sustainable Forest Management; FAO: Rome, Italy; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Linser, S.; Wolfslehner, B.; Bridge, S.R.J.; Gritten, D.; Johnson, S.; Payn, T.; Prins, K.; Raši, R.; Robertson, G. 25 years of criteria and indicators for sustainable forest management: How intergovernmental C&I processes have made a difference. Forests 2018, 9, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Brunette, M.; Leblois, A. The determinants of adapting forest management practices to climate change: Lessons from a survey of French private forest owners. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 135, 102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozgeris, G.V.; Brukas, A.; Stanislovaitis, M.; Kavaliauskas, M.; Palicinas, M. Owner mapping for forest scenario modelling—A Lithuanian case study. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 85, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessa Hegetschweiler, K.; Plum, C.; Fischer, C.; Brändli, U.B.; Ginzler, C.; Hunziker, M. Towards a comprehensive social and natural scientific forest-recreation monitoring instrument—A prototypical approach. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizaras, S.; Brukas, V.; Mizaraitė, D. Evaluation of forest management sustainability: Economic and social aspects. In Miškų Tvarkymo Darnumo Vertinimas: Ekonominiai ir Socialiniai Aspektai; Monograph; Lututė: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, G.; Lawrence, A.; Lidestav, G.; Feliciano, D.; Hujala, T.; Sarvašová, Z.; Dobšinská, Z.; Živojinović, I. Research trends: Forest ownership in multiple perspectives. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 99, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntymaa, E.; Juutinen, A.; Mönkkönen, M.; Svento, R. Participation and compensation claims in voluntary forest conservation: A case of privately owned forests in Finland. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juutinen, T.; Tolvanen, A.; Koskela, T. Forest owners’ future intentions for forest management. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Management in Sweden Current Practice and Historical Background, Skogsstyrelsen. Available online: https://www.skogsstyrelsen.se/globalassets/om-oss/rapporter/rapporter-2021202020192018/rapport-2020-4-forest-management-in-sweden.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Sukwita, T.; Darusman, D.; Kusmana, C.; Nurrachmat, D.R. Evaluating the level of sustainability of privately managed forest in Bagor, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2016, 17, 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- MCPFE. Forest Europe 1998. Annex 1 of the Resolution L2 Pan-European Criteria and Indicators for Sustainable Forest Management. In Proceedings of the Third Ministral Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe, Lisbon, Portugal, June 1998; p. 14. Available online: https://foresteurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/MC_lisbon_resolutionL2_with_annexes.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- MCPFE. State of Europe’s Forests 2003. Report on Sustainable Forest Management in Europe. Available online: http://www.foresteurope.org/documentos/forests_2003.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Forest Europe 2001. Criteria and Indicators for Sustainable Forest Management of the FOREST EUROPE: Review of Development and Current Status. International Expert Meeting on Monitoring, Assessment and Reporting on the Progress Towards Sustainable Forest Management; Tokyo, Japan. p. 13. Available online: http://www.ci-sfm.org/uploads/Documents/2012/Virtualproc.20Library/Policyproc.20Documents/FORESTEUROPE,2001a.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Mendoza, G.A.; Hartanto, H.; Prabhu, R.; Villanueva, T. Multicriteria and critical threshold value analyses in assessing sustainable forestry: Model development and application. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 15, 25–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfslehner, B.; Vacik, H.; Lexer, H.J. Application of the analytic network process in multicriteria analysis of sustainable forest management. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 207, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linser, S.; O’Hara, P. Guidelines for the Development of a Criteria and Indicator Set for Sustainable Forest Management; ECE/TIM/DP/73,92. United Nations and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Geneva, Switzerland; Available online: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/timber/publications/DP-73-ci-guidelines-en (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- State of Europe’s Forests 2011. Status and Trends in Sustainable Forest Management in Europe. Available online: https://www.foresteurope.org/documentos/State_of_Europes_Forests_2011_Report_Revised_November_2011.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Janová, J.; Hampel, D.; Kadlec, J.; Vrška, T. Motivations behind the forest managers’ decision making about mixed forests in the Czech Republic. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 144, 102841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, J.E.; Straka, T.J.; Greene, J.L. The Size of Forest Holding/Parcelization Problem in Forestry: A Literature Review. Resources 2013, 2, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B.; Caputo, J.; Robillard, A.; Sass, E. Size Matters: The Relevance of Size of Forest Holdings Among Private Forest Ownerships. In Proceedings of the IUFRO 3.08.00 Small-Scale Forestry 2019 Conference Proceedings, Duluth, MN, USA, 8–10 July 2019; University of Minnesota: Duluth, MN, USA, 2019; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, S.A.; Butler, B.J.; Markowski-Lindsay, M. Small-Area Family Forest Ownerships in the USA. Small-Scale For. 2019, 18, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficko, A.; Boncina, A. Probabilistic typology of management decision making in private forest properties. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 27, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizaras, S.; Doftartė, A.; Lukminė, D.; Šilingienė, R. Sustainability of Small-Scale Forestry and Its Influencing Factors in Lithuania. Forests 2020, 11, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuliešius, A.; Prūsaitis, R. Europos Šalių Miškų Ūkis Plėtojamas Darnaus Miškininkavimo Keliu. 2011. Available online: http://www.forest.lt/go.php/lit/t/3703 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Riepšas, E. Rekreacinė Miškininkystė (Vadovėlis Aukštosioms Mokykloms); ASU Leidybos Centras: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2012; p. 255. [Google Scholar]

- Ficko, A. Private Forest Owners’ Social Economic Profiles Weakly Influence Forest Management Conceptualizations. Forests. 2019, 10, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Europe. State of Europe’s Forests 2015; Forest Europe: Madrid, Spain, 2015; p. 314. Available online: https://www.foresteurope.org/docs/fullsoef2015.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Winkel, G.; Kaphengst, T.; Herbert, S.; Robaey, Z.; Rosenkranz, L.; Sotirov, M. Eu Policy Options for the Protection of European Forests against Harmful Impacts; Final report to the European Commission; University of Freiburg, Ecological Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2009; p. 146. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, F.E.; Rametsteiner, E.; Kleinn, C. User-oriented national forest monitoring planning: A contribution to more policy relevant forest information provision. Int. For. Rev. 2014, 16, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranovskis, Ģ.; Nikodemus, O.; Brūmelis, G.; Elferts, D. Biodiversity conservation in private forests: Factors driving landowner’s attitude. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 266, 109441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pynnönen, S.; Paloniemi, R.; Hujala, T. Recognizing the interest of forest owners to combine nature-oriented and economic uses of forests. Small-Scale For. 2018, 17, 443–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polomé, P. Private Forest owners’ motivations for adopting biodiversity-related protection programs. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, S.M.; Butler, B.J.; Markowski-Lindsay, M. Family Forest Owner Characteristics Shaped by Life Cycle, Cohort, and Period Effects. Small-Scale For. 2017, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gençay, G.; Birben, Ü.; Durkaya, B. Effects of legal regulations on land use change: 2/B applications in Turkish forest law. J. Sustain. For. 2018, 37, 804–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvan, O.D.; Birben, Ü.; Özkan, U.Y.; Yıldırım, H.T.; Türker, Y.Ö. Forest fire and law: An analysis of Turkish forest fire legislation based on Food and Agriculture Organization criteria. Fire Ecol. 2021, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, H.E.; Birben, Ü.; Elvan, O.D. Public perception of forest crimes: The case of Ilgaz Province in Turkey. Crime Law Soc. Chang. 2021, 75, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, D.; Bouriaud, L.; Brahic, E.; Deuffic, P.; Dobsinska, Z.; Jarsky, V.; Lawrence, A.; Nybakk, E.; Quiroga, S.; Suarez, C.; et al. Understanding private forest owners’ conceptualization of forest management: Evidence from a survey in seven European countries. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachova, J. Forests in the Czech Public Discourse. J. Landsc. Ecol. 2018, 11, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumpach, C.; Dwivedi, P.; Izlar, R.; Cook, C. Understanding perceptions of stakeholder groups about Forestry Best Management Practices in Georgia. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 213, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiebel, M.; Mölder, A.; Plieninger, T. Conservation perspectives of small-scale private forest owners in Europe: A systematic review. Ambio 2022, 51, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficko, A.; Lidestav, G.; Ní Dhubháin, Á.; Karppinen, H.; Zivojinovic, I.; Westin, K. European private forest owner typologies: A review of methods and use. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 99, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B. USDA Northern Research Station Home Page Scientists and Stuff. Bret Butler. Available online: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/people/bbutler01 (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Joa, B.; Schraml, U. Conservation practiced by private forest owners in Southwest Germany: The role of values, perceptions and local forest knowledge. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 115, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gossum, P.; Luyssaert, S.; Serbruyns, I.; Mortier, F. Forest groups as support to private forest owners in developing close-to-nature management. For. Policy Econ. 2005, 7, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widman, U. Shared responsibility for forest protection? For. Policy Econ. 2015, 50, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doftartė, A.; Mizaras, S.; Lukminė, D. Lietuvos privačių miškų ūkio darnumo įvertinimo rodiklių analizė [Analysis of indicators determining sustainability of Lithuanian private forestry]. Miškininkystė 2019, 2, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Brukas, V.; Stanislovaitis, A.; Kavaliauskas, M.; Gaižutis, A. Protecting or destructing? Local perceptions of environmental consideration in Lithuanian forestry. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işıkoğlu, N. Eğitimde nitel araştırma. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2005, 20, 158–165. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, A.; Şimşek, H. Sosyal Bilimlerde Nitel Araştırma Yöntemleri, 10th ed.; Seçkin Yayıncılık: Ankara, Türkiye, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, İ.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Theme | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Benefits of the database’s establishment | Identification of problems |

| Political decisions, legal regulation, legislation, forestry management | |

| Measures and methods for forestry efficiency |

| Level 1: Goal | Selecting socio-economic indicators to establish a database of Lithuanian private forest owners | |

| Level 2: Criteria | Social | Economical |

| Level 3: Index | Holding area | Income from forest management |

| Forest group | Income from 1 ha | |

| Owner’s age | Income by activity areas | |

| Residence | Main cost groups | |

| Education | Investments in forests | |

| Knowledge of forestry | Subsidies, grants, support | |

| Annual number of working days in forests | ||

| Form of farming | ||

| Forestry objectives | ||

| Form of ownership | ||

| Forest property acquisition form | ||

| Theme | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Database interference and risks | Negative attitudes of forest owners |

| Database establishment organization problems | |

| Data submission |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perkumienė, D.; Doftartė, A.; Škėma, M.; Aleinikovas, M.; Elvan, O.D. The Need to Establish a Social and Economic Database of Private Forest Owners: The Case of Lithuania. Forests 2023, 14, 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14030476

Perkumienė D, Doftartė A, Škėma M, Aleinikovas M, Elvan OD. The Need to Establish a Social and Economic Database of Private Forest Owners: The Case of Lithuania. Forests. 2023; 14(3):476. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14030476

Chicago/Turabian StylePerkumienė, Dalia, Asta Doftartė, Mindaugas Škėma, Marius Aleinikovas, and Osman Devrim Elvan. 2023. "The Need to Establish a Social and Economic Database of Private Forest Owners: The Case of Lithuania" Forests 14, no. 3: 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14030476

APA StylePerkumienė, D., Doftartė, A., Škėma, M., Aleinikovas, M., & Elvan, O. D. (2023). The Need to Establish a Social and Economic Database of Private Forest Owners: The Case of Lithuania. Forests, 14(3), 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14030476