1. Introduction

Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) are products of biological origin derived from forests but not timber. In the European natural products industry, various NTFPs are increasingly used in food, cosmetics, and health-promoting products [

1]. Despite using, for example, wild berries and mushrooms commonly in households for food and nutritional diversity in Finland, the direct monetary value of NTFPs is still minor compared to timber. Their potential use in products with high-added-value and opportunities in the forest-based bioeconomy are recognised, but boosting NTFP value chains is still needed both globally [

2] and in the Finnish rural bioeconomy [

3]. The production of NTFPs not covered by everyman’s right, for example, cultivating wood-decay mushrooms on living trees, cutting logs, and stumps, could create significant additional income for forest owners compared with timber production alone [

4]. The global market for reishi mushrooms (

Ganoderma lucidum) has been valued at USD 3097 million in 2019 and is estimated to reach USD 5000 million by 2027 [

5]. However, the cultivation of, e.g., reishi on stumps is new, and the perspectives of forest owners, as well as other supply chain actors covering the activities from cultivation to processing, are not known.

New value chains based on specialty mushroom cultivation have recently been introduced to Finnish forestry. For example, living birch trees (

Betula spp.) are inoculated with pakuri (

Inonotus obliquus) by drilling holes in the trunk and installing inoculation plugs in the holes [

6]. Cultivating pakuri on low-quality birch trees has no effect on timber production. Pakuri cultivation is already well-established in Finland; several companies offer forest owners pakuri cultures and a service for cultivation.

Specialty wood-decay mushrooms (e.g., reishi) can be cultivated on cutting stumps without any effect on timber production. The cultivation of pakuri on living trees requires a lot of manual work and time, but a more efficient technique can be used in mushroom cultivation on stumps. Wood-decay mushrooms could be inoculated in connection with harvesting operations, such as spreading biological control agents (i.e., spore suspension of competitive saprotrophic fungus

Phlebiopsis gigantea) in stump treatment against

Heterobasidion spp. root rot. In stump treatment, a biological or chemical substrate (urea) is sprayed on the stump surface of coniferous trees using a harvester equipped with stump treatment facilities. Currently, ongoing research projects aim to identify potential stands and sites for production and develop methods and materials for inoculation of specialty wood-decay mushrooms. Specialty mushroom species are collected from naturally grown forests, but they are rare [

7]; thus, their cultivation increases the quantity of raw material supplied to the market. However, turning mushroom cultivation into a viable business opportunity requires careful consideration of the perspectives of all supply chain actors [

8].

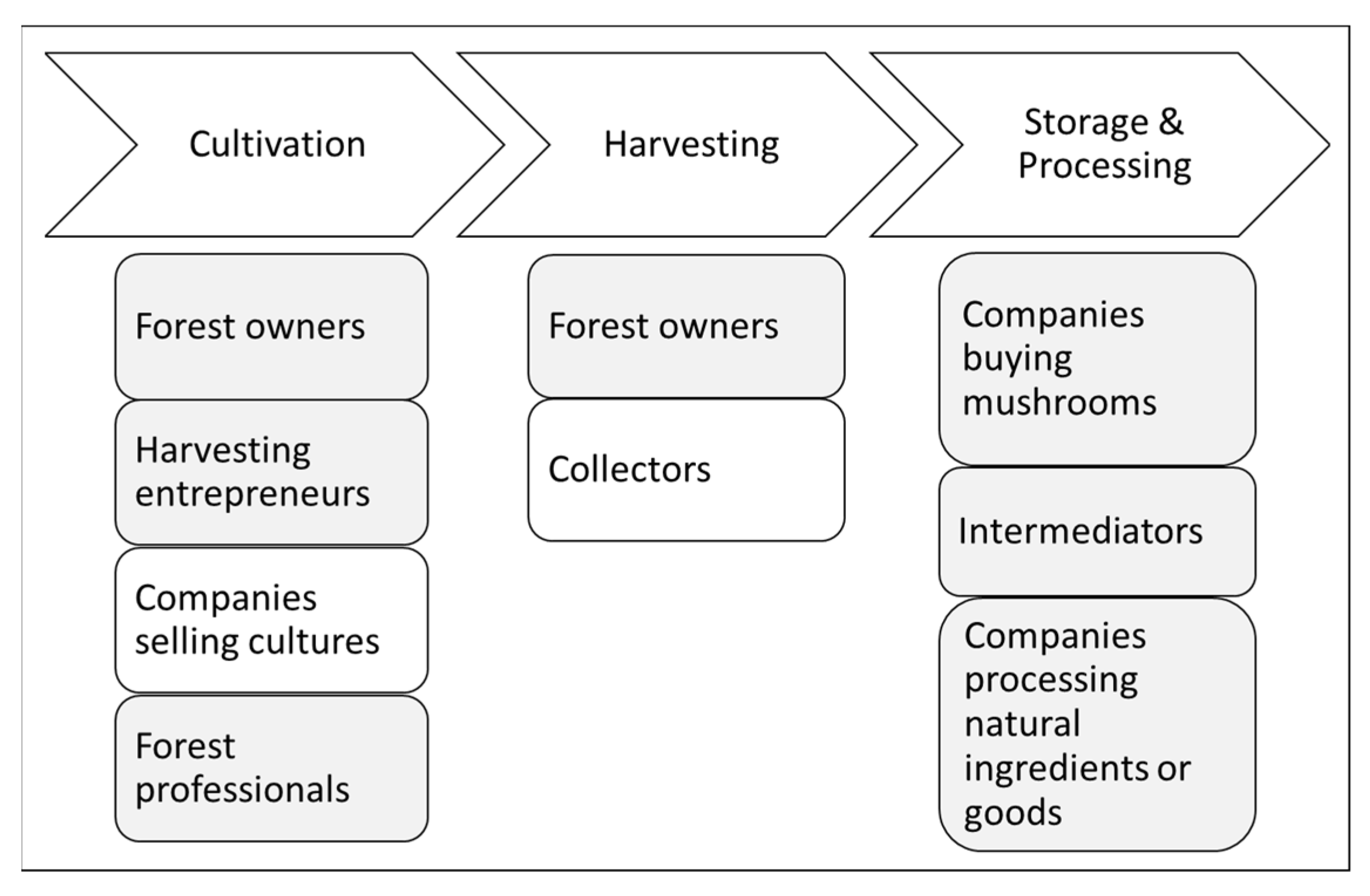

Several actors are involved in the supply chain of specialty mushrooms cultivated on stumps. In our case, the supply chain is a connected string of actors involved in the production, supply, and demand of specialty mushrooms. The key issue is the involvement of supply chain actors. To establish an efficient supply chain, (1) forest owners’ interest in producing mushrooms in their forests, (2) the readiness of harvesting entrepreneurs to spread mushroom cultures in connection with harvesting, (3) the support of forest professionals to advise and act as mediators between forest owners and harvesting entrepreneurs in cultivation, and (4) the current and future need for specialty mushrooms in the natural products industry in Finland should be investigated. Forest owners play a major role in the production and availability of specialty mushrooms, the harvesting of which requires the forest owner’s permission, as cultivated NTFPs are not under everyman’s right [

9].

In Finland, the challenges of NTFP-based businesses are the stable availability of raw materials, small domestic markets, long distances to foreign markets, and the lack of consistent co-operation networks throughout the value chain [

10]. Forest owners may not be committed to NTFP production or aware of the opportunities in their forests. To increase the awareness of forest owners, the Metsään.fi service of the Finnish Forest Centre presents potential forest sites for, e.g., mushroom cultivation to forest owners to support decision making [

11]. Before investing in NTFP production, forest owners need information on yields, markets, costs, effects on timber production, and profitability analyses on NTFP production. Additionally, more effective communication, co-operation, and networking between the actors of the NTFP supply chain are necessary. In particular, new knowledge, technologies, and innovations would support the NTFP supply chain, and consequently the development of the NTFP business in rural areas while advocating for NTFPs as a relevant part of the Finnish bioeconomy [

3].

Forest owners’ interest in producing NTFPs in their forests vary depending on forest ownership motives [

12]. Muttilainen and Vilko [

13] identified several factors affecting forest owners’ decision to produce NTFPs with timber. Internal drivers such as increased knowledge, more effective communication, co-operation and networking among forest owners, forest professionals, and natural product entrepreneurs were found to support NTFP production and supply chains. Barriers which hinder starting or operating in NTFP business were mainly external (e.g., high investments costs, few buyers, uncertain demand, year-to-year variation in yields, regulations, and bureaucracy). Thus, forest owners should consider various factors before starting mushroom cultivation on stumps and participating in the supply chain.

Rogers [

14] distinguished the properties of innovation that affect the adoption of innovations. To be adopted, an innovation needs to be perceived as being trailable, compatible, easily and safely adopted, positively implemented, and giving benefits compared to the existing practice. Specialty mushroom cultivation on stumps could be regarded as an innovation fulfilling these features. Adopting the innovation starts with gaining knowledge about it and evaluating its positive and negative aspects [

14]. Implementing and especially adopting the innovation in practice may take a long time. In the innovation-adoption process, so-called innovators and early adopters demonstrate and pilot the practice and thus act as peer actors in the supply chain of specialty wood-decay mushrooms. According to Rogers [

14], early adopters typically have a higher education, social status, and income. In forestry, innovation activity among Central European forest holdings is clearly correlated with the size of the forest holding [

15].

The aim of the study was to analyse the perspectives of forest owners, forest harvesting entrepreneurs, forest professionals, and natural product entrepreneurs on specialty wood-decay mushrooms and to investigate their interests in mushroom cultivation on stumps in Finland. These actors were seen as key operators in a supply chain of specialty mushrooms. The perspectives were determined by questionnaires sent to forest owners in the North Karelia and South Savo regions and to forest harvesting entrepreneurs, forest professionals, and natural product entrepreneurs throughout the country. Due to the importance of forest owners in the supply chain, special emphasis was placed on forest owners’ interests concerning mushroom cultivation in their forests. We hypothesised that forest owners’ demographics, background variables (e.g., forest area, place of residence, silvicultural operations done, and acquisition of forest holdings), ownership motives and perspectives regarding NTFPs affect their interest in cultivating mushrooms. We also studied barriers inhibiting the partnership of harvesting entrepreneurs, forest professionals, and natural product entrepreneurs in the production and utilisation of specialty mushrooms. The results can be utilised to promote and adopt mushroom cultivation in forests and to manage the supply chain of specialty wood-decay mushrooms in Finland.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

The perspectives of actors in the cultivation of specialty wood-decay mushrooms were assessed using web-based questionnaires sent to forest owners, forest harvesting entrepreneurs, forest professionals, and natural product entrepreneurs in Finland (

Figure 1). All four questionnaires contained structured and open-ended questions concerning respondent demographics, such as age, gender, level of education, geographic location (

Table 1), and specialty mushrooms (e.g., familiarity with species and mushroom cultivation). In particular, respondents were asked if they were interested in participating as actors in the supply chain of specialty mushrooms cultivated on stumps. In addition, each questionnaire contained actor-specific questions related to their backgrounds and roles in the supply chain. The data were collected via email using a Webropol survey. Sending reminders increased response rates.

The target population of the study was non-industrial private forest owners owning a forest holding in the North Karelia or South Savo regions. The questionnaire was sent to all adult forest owners (private, estate) who owned a forest holding in the regions and who had an email address in the Finnish Forest Centre’s customer register without a marketing ban. This resulted in a sample size of 16,822 forest owners (35% of the total number of forest owners in the regions). The data were collected in September–October 2021. A total of 2405 responses were received, with a response rate of 14.3%.

In addition to respondent demographics, background variables, such as occupation, forest area, place of residence, silvicultural operations done, and size and acquisition of forest holdings, were queried (

Table 2). Forest owners were asked, for example, whether they were familiar with biological and chemical stump treatment against

Heterobasidion spp. Two structured questions were used to determine forest owners’ motives towards forest owning and perspectives towards and utilisation of NTFPs. Motives and perspectives were studied, respectively, with 15 and 11 attitudinal statements adopted from [

12], which were rated by the respondents using a five-point Likert scale and the descending order of the scale options. For data analysis, the scale was reversed so that 1 revealed the weakest motive and perspective corresponding to “Not important” and “Strongly disagree,” respectively, and 5 revealed the strongest motive and perspective corresponding to “Very important” and “Strongly agree,” respectively. For analysis, the answers “I cannot say” were recoded as “Neutral” (scale 3).

The perspectives of Finnish forest harvesting entrepreneurs towards NTFPs and especially mushroom cultivation in connection with timber harvesting were studied in June–August 2021. The questionnaire was sent to a total of 962 entrepreneurs whose email addresses were obtained from the register of the Trade Association of Finnish Forestry and Earth Moving Contractors (710 entrepreneurs) and the Finnish Forest Centre’s customer register (252 entrepreneurs, mainly from North Karelia and South Savo). A total of 105 responses were received, with a response rate of 10.9%.

Forest harvesting entrepreneurs were asked questions concerning whether they use biological and/or chemical substrates in stump treatment, who chooses the substrate, whether they are willing to change the chemical substrate (urea) to a biological one (Phlebiopsis gigantea), how often forest owners ask which substrate is used and ask to change the urea substrate to a biological one, and whether there are any differences in applying these two substrates. In addition, they were asked whether they could market and provide specialty mushroom cultivation to forest owners in connection with timber harvesting.

The perspectives of forest professionals in Finland were studied in March–April 2022. The questionnaire was sent to a total of 2095 forest professionals whose email addresses were obtained from the webpages of the following forest organisations: Metsä Group, Metsä Forest (n = 49), Tornator Oyj (n = 83), Stora Enso Oyj Forest (n = 179), UPM-Kymmene Oyj Forest (n = 211), Metsähallitus (n = 342), the Finnish Forest Centre (n = 543), and Forest Management Associations (n = 688). A total of 229 responses were received, with a response rate of 10.9%. The questionnaire contained questions concerning the respondent’s employer and work tasks, and whether the respondent’s organisation harvests timber. Forest professionals were also asked whether they could market specialty mushroom cultivation to forest owners in connection with timber harvesting.

The perspectives of Finnish natural product entrepreneurs towards NTFPs and especially specialty wood-decay mushrooms were studied in January 2022. The Webropol survey was sent via email to a total of 551 entrepreneurs utilising NTFPs as raw materials. Entrepreneurs’ email addresses were obtained from the Finnish Forest Centre’s customer register and the public lists of the members of the Finnish Food and Drink Industries’ Federation, the Finnish Nature-based Entrepreneurship Association, and Arctic Flavours Association. A total of 38 responses were received, with a response rate of 6.9%.

The questionnaire contained questions concerning the enterprise, natural raw materials used, and the current and future intention to utilise mushrooms in businesses. Entrepreneurs were asked how they acquired raw mushroom material, if any, and in which form (fresh, fried, dried, or extract) raw mushroom material would be the most suitable for them. Natural product entrepreneurs who responded to the survey mainly used wild berries (79%), herbs (71%), and mushrooms (66%) in their business. Tree-origin natural products, such as spruce shoots and branches, resin, bark, and pakuri, were used by 66% of the responding enterprises, and some of them also used cultivated berries (26%).

2.2. Data Analysis

Separate principal component analyses (PCA) with varimax rotation were used to reveal the factors of forest owners’ motivations and perspectives [

17]. PCAs were conducted with the FACTOR procedure in IBM SPSS Statistics 28 (IBM Inc. 2021, Armonk, NY, USA). Using the statements of the questions, separate principal component analyses were conducted for respondents’ motives towards forest owning and perspectives towards and utilisation of NTFPs, such as berries and mushrooms. The scores of the principal components were calculated as linear combinations of all the statements of the question. In further analyses, the PC scores were interpreted as normally distributed continuous variables. To study the internal consistency of the statements of the question, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated using the RELIABILITY procedure.

Based on the PC score variables, forest owners were grouped using K-means cluster analysis and the QUICK CLUSTER procedure in IBM SPSS Statistics 28 [

18]. Two groupings were formed using the PC scores describing (1) motives towards forest owning and (2) perspectives towards and utilisation of NTFPs. Several solutions with a different number of clusters were tested, and then the best clustering was selected based on the interpretability of the solution for the given data [

19]. The final cluster centres, i.e., the characteristics of the typical case for each cluster, were used to name the forest owner groups.

Relationships among the PC score variables of forest owners’ motives towards forest owning and perspectives towards and utilisation of NTFPs were analysed using Cohen’s set correlation coefficients calculated with the function setCor in R [

20].

A logistic regression analysis was used to study the differences between the identified forest owner groups concerning their interest in cultivating specialty mushrooms. The background variables of demographics, forest holding, and forest owner groups concerning ownership motives and the utilisation of NTFPs in their forests were included in the model as predictors. The aim was to identify those forest owners who indicated interest in participating in the supply chain and had commercialised the NTFPs of their forests or were willing to do so. These forest owners would be the targets advised to cultivate specialty wood-decay mushrooms on stumps in their forests.

Pearson’s χ2 test of homogeneity was used to test for differences among the respondent groups (forest owners, harvesting entrepreneurs, forest professionals, and natural product entrepreneurs), for example, in their interest in specialty mushroom cultivation in connection with harvesting. In all analyses, listwise deletion was applied, i.e., an entire record was excluded if any single value was missing.

3. Results

3.1. Forest Owners’ Objectives and Utilisation of NTFPs

Outdoor recreation, forest work as exercise, preserving biodiversity, and the landscape were the most important motives the forest owners gave for using their forest holdings (important or very important for 66%–70% of respondents) (

Table 3). About 60% of the respondents considered it important to collect berries and mushrooms, but only 12% produced special NTFPs, such as birch sap, pakuri, spruce sprouts, and resin, in their own forest.

Four principal components (PC) were extracted based on the statements concerning forest ownership motives (

Table 3). Based on the absolute loadings > 0.5, the first PC called Multiple-use, recreation included sources of firewood, forest work, outdoor recreation, berry and mushroom picking, and hunting. The second PC, Conservation, included biodiversity preservation, nature conservation, and landscape. The statements about outdoor recreation, berry and mushroom picking, and the production of special NTFPs also contributed to this PC. The third PC, Timber production, included timber selling as regular additional incomes, financial security, source of primary income, and asset investment. The fourth PC, Inheritance, described forest owners’ intention to resign and leave the forest property to the next generation, and it consisted of motives such as the joy of ownership, inheritance, and asset investment.

In the K-means cluster analysis, two forest owner groups were formed using the PC score variables for their motives for forest ownership (

Table 4). The first group consisted of multi-purpose forest owners, since in the grouping, the PC score variables Multiple-use, recreation and Timber production contributed positively to this group. The PC score variables Conservation and Inheritance contributed to the second group, representing the saver type of forest owners. The contribution of the PC score variable Timber production was minor compared to the other PC score variables.

Most forest owners stated that they use their forests in various ways (

Table 5). As many as 79% of the forest owners collected berries and mushrooms for their own use, but only 14% collected them for sale, and only 6% produced special natural products for sale. However, half of the respondents were interested in the production of special NTFPs, which can be collected only with the forest owner’s permission. More than a third of the respondents were willing to give permission to use their forests for special NTFPs.

Three principal components (PC) were formed based on the statements concerning the utilisation of NTFPs (

Table 5). The first PC, called Permission and knowledge, included statements in which the forest owner was willing to hand over information about the potential to produce natural products to entrepreneurs, to give permission to utilise the special NTFPs of their forests, and to themselves utilise their forests for tourism or programme services. The PC also included statements in which the forest owner needed more information about how they could use their forests in a variety of ways, and how natural product production might affect timber production. A statement concerning forest owner’s interest in producing special NTFPs was also loaded to the PC Permission and knowledge.

The second PC, Commercial use, included picking natural products covered or not covered by everyman’s right for sale. The statements of NTFP utilisation for own use, and the utilisation of the forest in various ways, not only in timber production, were included in the third PC, Own use.

In the K-means cluster analysis, three forest owner groups were formed based on the PC score variables on the utilisation of NTFPs (

Table 6). The first two groups consisted of household users and commercial pickers, since in the grouping, the PC score variables Own use and Commercial use, respectively, contributed positively to these groups. The PC score variable Permission and knowledge contributed to the third group representing permit providers and those forest owners who needed additional information about how they could diversify the utilisation of their forests.

The relationships among forest owners’ ownership motives and perspectives concerning non-timber products were analysed with canonical correlation (

Table 7). Forest owners who had the ownership motives, Multiple-use, recreation or Conservation, harvested NTFPs for their own use. Conservationists or timber producers were willing to give permission for their forests to be utilised in special NTFP production and tourism and programme services and to give information about NTFPs’ potential in their forests to companies. The PC score variables describing Multiple-use, recreation and Timber production were positively correlated with the PC score variable, Commercial use.

The frequencies of forest owner groups were cross-tabulated to explore the associations between the objectives of forest ownership and the utilisation of NTFPs (

Table 8). Based on the test of homogeneity (Pearson Chi square and Cramer’s V), the utilisation of NTFPs was dependent on forest ownership motives. In the group of multi-purpose owners, commercial picking was more common than in the saver type of owner group, whereas permits would be provided more commonly by the saver type of owner. The proportion of household users did not differ between the two groups of forest owners.

3.2. Supply Chain Actors’ Awareness of and Interest in Cultivating Specialty Mushrooms

Awareness of specialty mushroom species varied significantly among supply chain actors (

Table 9). Natural product entrepreneurs (82%) were most and harvesting entrepreneurs (37%) were least familiar with specialty mushrooms. The most known species were pakuri, shiitake, champignon, oyster mushroom, and sheathed woodtuft. The level of awareness for reishi varied most by supply chain actor; 60% of natural product entrepreneurs had heard about the species, but less than 10% of forest owners and harvesting entrepreneurs had heard of it.

Additionally, the awareness of specialty mushroom cultivation varied significantly among supply chain actors (

Table 10). Forest professionals (42%) and natural product entrepreneurs (42%) were more familiar with specialty mushroom cultivation than forest owners (15%) and harvesting entrepreneurs (13%). Forest professionals (34%) were most interested in specialty mushroom cultivation in co-operation with companies selling cultures or buying mushrooms, whereas about a fourth of the forest owners (23%) indicated that interest (

Table 10). Half of the forest owners indicated doing the cultivation by themselves (12%), and half were willing to lease their forest for mushroom cultivation (11%, the results are not shown in

Table 10). As many as 37%–58% of the respondents could not say or needed more information about specialty mushroom cultivation on stumps. Forest owners and professionals, more often than harvesting entrepreneurs, believed that mushroom cultivation could increase the profitability of forest management.

A multinomial logistic regression model was fitted to describe the differences between forest owners who had an interest in cultivating specialty mushrooms in their forests, who were not interested (as reference), and who could not say, or needed more information. In modelling, forest owners’ demographics, background variables (e.g., forest area, place of residence, silvicultural operations done, and acquisition of forest holdings), NTFP utilisation and ownership motives were used as potential predictors. Predictors such as part-time forestry entrepreneurship, younger age, male gender, and higher education significantly increased the odds of interest in participating in specialty mushroom cultivation (

Table 11). In addition, forest owners classified as savers (compared to multi-purpose forest owners), as well as commercial pickers and permission providers (compared to household users) were more interested in mushroom cultivation.

Commercial pickers and permit providers were potential forest owners who may participate in NTFP-related businesses (

Table 11). A logistic regression model was estimated to describe the differences between the demographics and background characteristics of these forest owners (response = 1) compared to those of household users (response = 0). Compared to household users, predictors such as part-time forestry entrepreneurship, younger age, male gender, silvicultural operations done by hired operators or not done at all, and forest holdings donated or purchased significantly increased the odds of belonging to the Commercial picker or Permit provider groups (

Table 12). Forest owner grouping based on forest ownership motives was not a significant predictor in the logistic model.

Harvesting entrepreneurs were asked whether they could market and provide specialty mushroom cultivation services to forest owners in connection with timber harvesting. A fourth of the harvesting entrepreneurs (25%) indicated an interest in providing such cultivation services, 16% were not interested, 26% were unable to answer, and 33% needed more information.

Compared to harvesting entrepreneurs, forest professionals (44%) were more interested in marketing specialty mushroom cultivation to forest owners in connection with timber harvesting. About 12% of the forest professionals were not interested, 13% were unable to answer, and 32% needed more information.

Harvesting entrepreneurs were asked about the substrate used in stump treatment. Most commonly, only a chemical stump treatment (i.e., urea) was used (74%). Only biological stump treatment (Phlebiopsis gigantea) or both chemical and biological stump treatments were used, respectively, by 10% and 16%. If harvesting entrepreneurs used only urea, 66% were not willing to change the substrate, 26% were willing to change, and 9% could not say. Most harvesting entrepreneurs (71%) indicated that it was possible to spread both urea and Phlebiopsis gigantea substrates using the same equipment. The entrepreneur (63%) or the customer (31%) to whom timber is harvested chose the substrate. Forest owners seldom asked them to change the urea substrate to a biological one.

Natural product entrepreneurs were asked whether specialty mushrooms could be part of their business. Specialty mushrooms were already used by 26% of natural product enterprises, 29% of them needed more information, 40% indicated that specialty mushrooms could be used in the future, and only 5% that specialty mushrooms cannot be a part of their business. Natural product entrepreneurs currently use or could use specialty mushrooms in trading, processing, dyeing, health care products, foodstuffs, spices, and cosmetics.

Currently, the natural product entrepreneurs who utilise specialty mushrooms purchase specialty mushrooms from forest owners (8%), traders (16%), or pickers (21%), and 21% of them produce or harvest specialty mushrooms themselves. Entrepreneurs would like to purchase specialty mushrooms as dried (58%), extract (21%), fresh (18%), and/or fried (16%).

3.3. Knowledge Needs

More research results on cultivation success, yield, and costs, as well as profitability analyses of specialty mushroom cultivation were needed by all supply chain actors (

Table 13). Additionally, knowledge of potential stands for cultivation and mushroom markets were indicated as knowledge needs. The support of peer forest owners and the forest industry was also found to help the adoption of specialty mushroom cultivation on stumps.

4. Discussion

A better understanding of the perspectives of forest owners, forest harvesting entrepreneurs, forest professionals, and natural product entrepreneurs is needed to develop and adopt the supply chain for specialty wood-decay mushrooms cultivated on stumps in Finland. In this study, supply chain actors’ perspectives concerning specialty wood-decay mushrooms and their interests and possible barriers inhibiting the partnership in mushroom cultivation on stumps were identified. We especially studied the perspectives of forest owners because they have a key role in producing specialty wood-decay mushrooms. We assumed that forest owners’ motives for forest ownership and the use of NTFPs would explain their interest in mushroom cultivation.

Compared to the national survey of Finnish forest owners [

16], the forest owners who responded to our questionnaire were slightly higher educated, were more often female, less often owned an inherited forest, and had larger forest holdings than forest owners on average. According to Karppinen et al. [

16], forest owners with larger non-inherited holdings had more often multi-purpose motives for their forests. Thus, forest owners who are interested in the utilisation of forests in various ways may be overrepresented in our sample. The response rates, especially those of natural product entrepreneurs, were low, which must be considered when generalising the results of this study. Response rates of less than 20% have also been obtained in earlier Finnish forest owner surveys concerning NTFPs [

12,

21,

22]. Low response rates, using web-based questionnaires especially for forest owners who were elderly and maybe not so familiar with electronic devices, and the study’s data collected from a certain district weaken the possibilities to generalise the results. Most of the forest owners collected berries and mushrooms, but only 12% of the respondents produced special NTFPs in their forests. Outdoor recreation, forest work as exercise, preserving biodiversity, and the landscape were the most important motives that forest owners gave for using their forests [

12].

Two forest owner groups were formed based on their motives for forest ownership. The first group consisted of multi-purpose forest owners, who used their forests for outdoor recreation and timber production. The second group represented the saver type of forest owners, who preserve biodiversity and landscape and/or are resigning and leaving the forest holding to the next generation. In previous studies, forest owners have been classified into typologies called, for example, multi-objective, recreationists, investors, farmers, and indifferent [

16]. Three forest owner groups were formed based on the utilisation of NTFPs. The first two groups consisted of household users and commercial pickers, and the third group represented permit providers willing to sell licences for picking and gathering permits. The utilisation of NTFPs was dependent on forest ownership motives. Compared to the saver type of owner, commercial picking was more common for multi-purpose owners, whereas permits would be provided more commonly by the saver type of owner. Household users were equally common in the groups of multi-purpose and saver types of forest owners.

Natural product entrepreneurs were most familiar with specialty mushroom species and mushroom cultivation. Compared to other actors, natural product entrepreneurs were more aware of reishi having the potential for cultivation on stumps. A high proportion of the respondents (34%–50%, depending on the actor) were not able to say whether they were interested in participating in the supply chain or not. However, 23%–34% were interested in cultivation in co-operation with companies selling cultures or buying mushrooms. Forest owners were willing to both perform the cultivation by themselves and lease their forest for mushroom cultivation.

For forest owners, factors such as part-time forestry entrepreneurship, younger age, male gender, and higher education significantly increased forest owners’ interest in participating in mushroom cultivation on stumps. For example, higher education is in accordance with the characteristics of early adopters mentioned by Rogers [

14]. Additionally, commercial pickers or permission providers were more interested in cultivating specialty mushrooms on stumps. Compared to household users, commercial pickers or permit providers were more likely part-time forestry entrepreneurs, younger, male, to hire operators to do silvicultural operations, or not to do such operations at all. Furthermore, forest holdings donated or purchased significantly described the forest owners in the commercial pickers or permit provider groups.

Forest owners classified as savers were more interested in cultivating specialty mushrooms in their forests than multi-purpose forest owners. Saver-type forest owners consisted of owners whose motives for forest use were conservation and inheritance. Forest owners with the intention to resign and leave the forest holding to the next generation collected NTFPs for their own use only, while conservationists were willing to provide permits to use their forests rather than do the work themselves. It seems that conservationists preferred preserving nature, biodiversity, and landscape (

Table 3) but still see the production of NTFPs (

Table 7 and

Table 8) as a possible combination with these motives. This result is in line with previous results [

12], even though in this study conservationists appeared to be more active operators in the natural products sector.

Motivating supply chain actors, especially forest owners, through incentive actions could be used to encourage them to become active. The target group could be those owners who are part-time forestry entrepreneurs, commercial NTFP users, and/or willing to outsource specialty NTFP production and harvesting. According to Andersson and Keskitalo [

23], in particular, new private forest owners and owners residing in urban areas are expected to decrease family work and outsource mushroom cultivation, such as outsourcing forest management activities.

According to Haveri-Heikkilä [

24], Finnish forest owners have little knowledge of NTFP production, no interest in investing money in production, and lack straightforward trading channels. To have sustainable and functional value chains from forests to markets, these issues need to be addressed by, for example, generating a stable trading platform where supply and demand can meet and incentives for NTFP production [

13], such as those existing in timber production (

https://kuutio.fi/, accessed on 9 December 2022).

In addition to the stable supply from forests, the demand for specialty mushrooms by the natural products industry is equally important for the viable value network. Most of the natural product entrepreneurs who responded to the survey used a wide variety of wild natural products (e.g., berries, herbs, mushrooms, and tree-origin products) in their businesses. A fourth of the natural product entrepreneurs already used specialty mushrooms, and as much as 40% indicated that in the future, specialty mushrooms could be used in trading, processing, dye, health care products, foodstuffs, spices, and cosmetics. Currently, entrepreneurs obtain specialty mushrooms from different sources (e.g., forest owners, traders, pickers, or produce themselves) and in different forms (e.g., dried, extract, fresh, or fried). The results indicate that in the supply chain, intermediators with storage and pre-treatment facilities are also needed to ensure a smooth flow of raw materials to enterprises [

10].

All supply chain actors needed more information on, for example, cultivation success, yield, and costs, as well as profitability analyses on specialty mushroom cultivation. Thus, research and development work developing inoculation cultures, cultivation techniques, etc., is important to support supply chain actors. Though more knowledge on cultivation is gained through ongoing research, the lack of information is currently the most serious barrier inhibiting partnerships in the production and utilisation of specialty mushrooms. Examples of successful cultivation, peer support, and support by forest owners’ associations, forest companies, timber purchasing organisations, etc., but also broadly the bioeconomy sector, would help to promote and adopt specialty mushroom cultivation on stumps in connection with timber harvesting.

The results indicate that there is a need for new tailored services (e.g., advisory and information services, inventory and planning, mushroom cultivation, harvesting, and marketing) and products (e.g., inoculation cultures) in Finland. In many countries, research-based guidelines and services are available for cultivating specialty wood-decay mushrooms, for example, shiitake, oyster and reishi on logs or stumps in forests [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. In Finland, some of these services are directly or indirectly linked to timber production and harvesting and, therefore, could be provided by the current operators with the expertise and know-how. Currently, finding forest professionals with the above-mentioned expertise can be challenging. In the future, integrating NTFPs (including mushroom cultivation) into forest management planning will increase forest owners’ income-earning potential.

Support services could play a specific role among the multiple actors involved in the supply chain [

30]. Service providers would, for example, link the actors, facilitate innovation through the supply chain, organise joint marketing, and provide information and decision support for forest owners and entrepreneurs. Effective support, communication, and information sharing are important for diffusing mushroom cultivation at the scale necessary to produce viable new businesses and economic impact for rural development.

Knowledge management is crucial in the supply chain of NTFPs [

10,

13]. In our case, actors should know about potential sites available for specialty wood-decay mushroom cultivation, mushroom yields on different tree species and growing sites, mushroom markets, etc., and other actors involved in the supply chain. For that, data platform(s) are needed to acquire, share, apply, and convert relevant data into a useful form for the actor. Knowledge management also decreases the uncertainty and risk involved in the supply chain. Such a data platform should also allow traceability and certification of raw materials and final products. The partnership in the supply chain of cultivated mushrooms is characterised by small efforts and low risk because no big changes are required in existing practices. For example, mushrooms can be inoculated on stumps using existing equipment, but the harvesting entrepreneur must be willing to change the urea substrate to a biological one. From the forest owner’s point of view, it is not enough that they agree on mushroom cultivation with the harvesting entrepreneur, but it should be guaranteed that fruiting bodies will be harvested and purchased as well. Therefore, successful co-operation requires a business advantage and overlapping motivations among all involved actors.