Implementing Local Climate Change Adaptation Actions: The Role of Various Policy Instruments in Mopane (Colophospermum mopane) Woodlands, Northern Namibia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

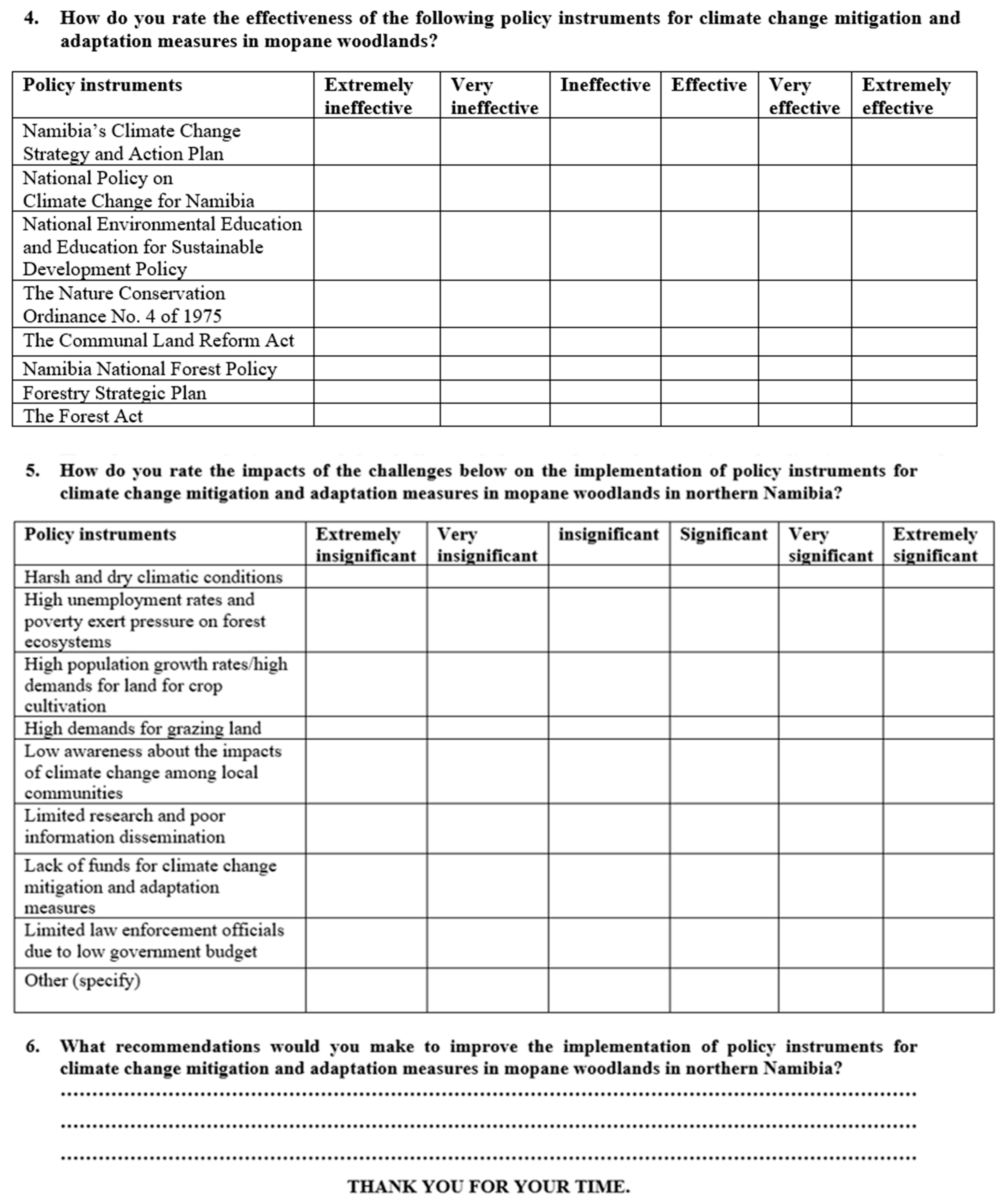

2.1. Study Area

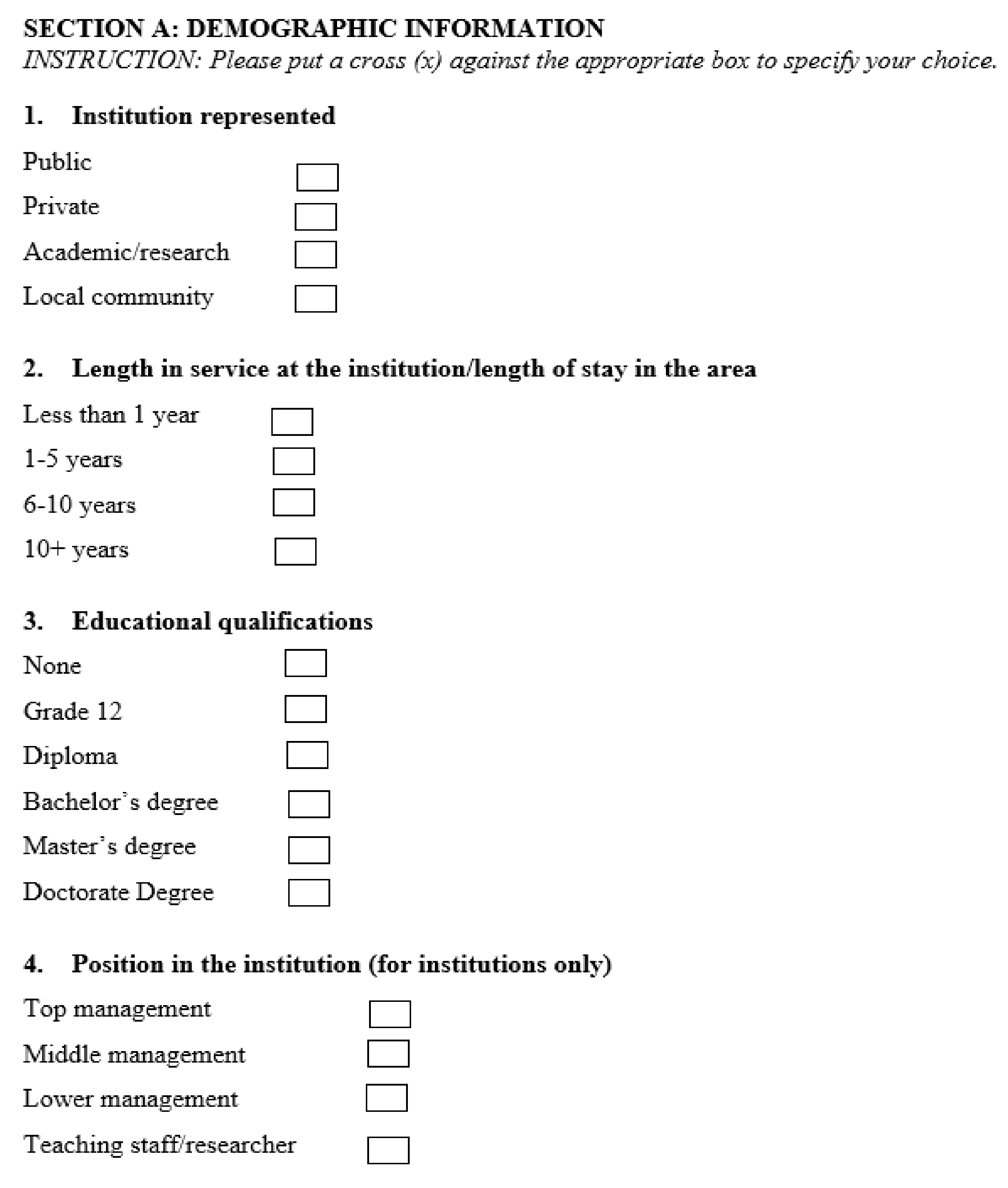

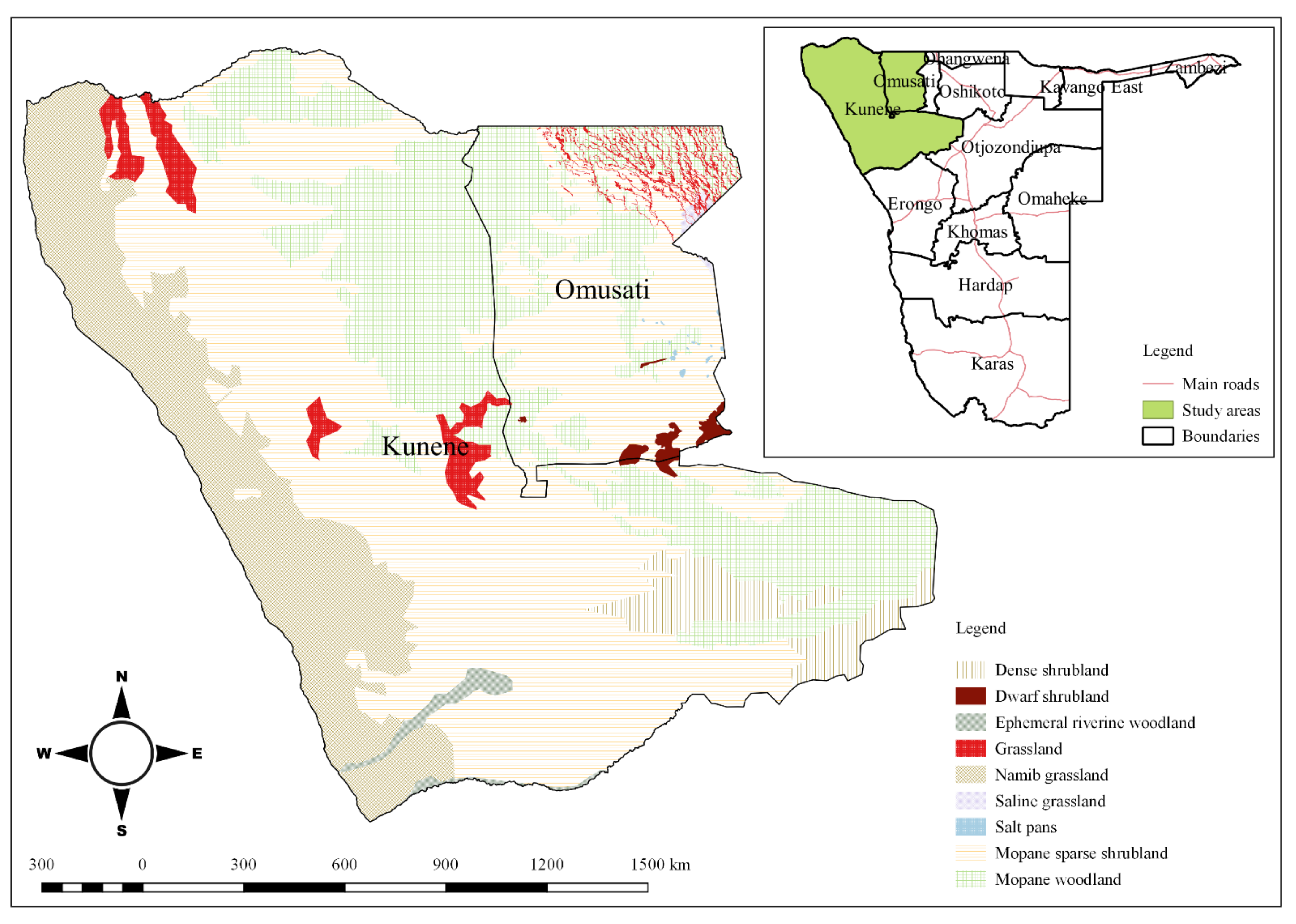

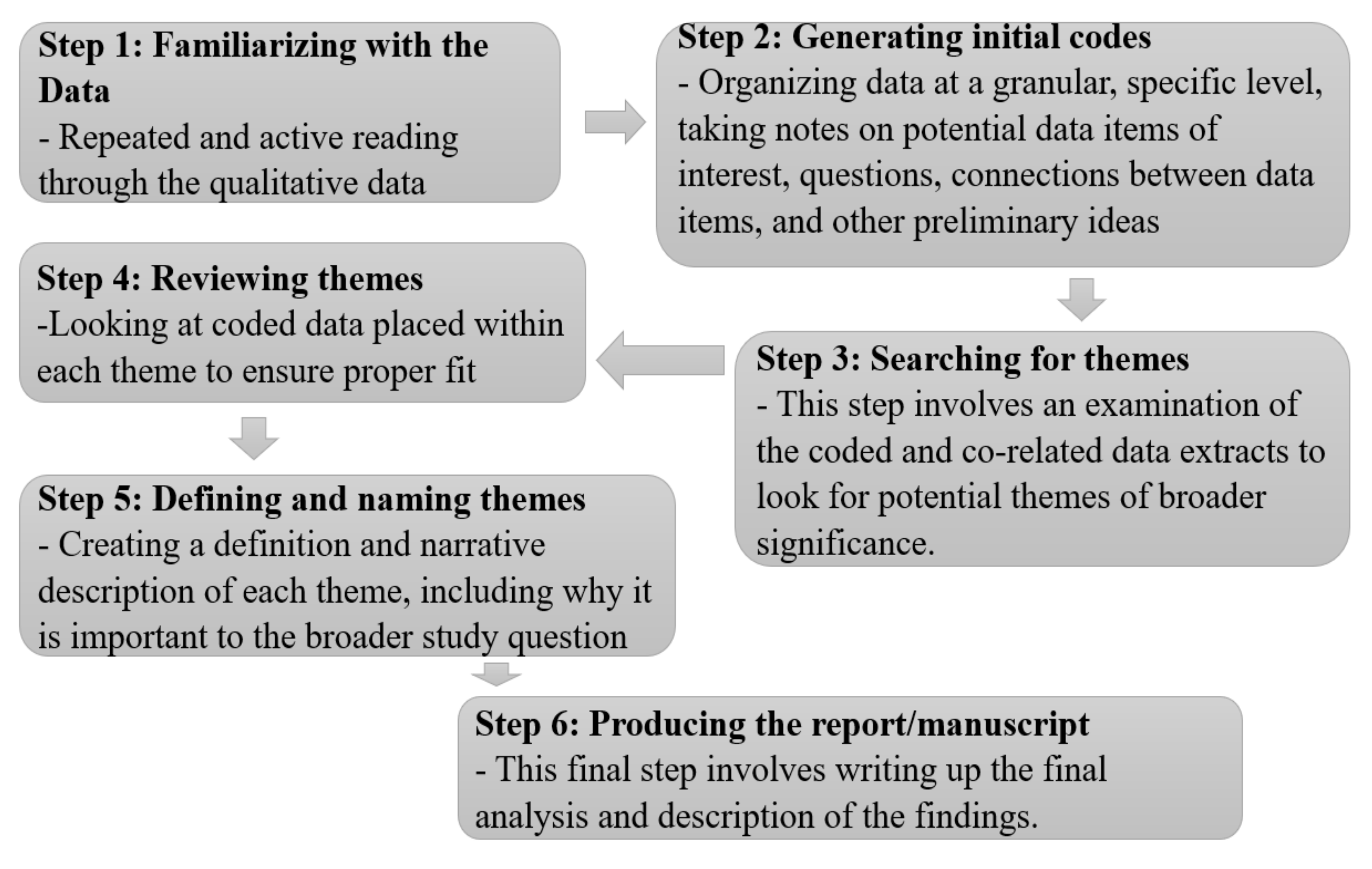

2.2. Survey

3. Results

3.1. Level of Education

3.2. Knowledge of Policy Instruments for Climate Change

3.3. The Implementation of Policy Instruments

3.4. Effectiveness of the Policy Instruments

3.5. Implementation Strategies

3.6. Challenges

3.7. Possible Improvements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Prospects for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Educational Level | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | Valid Percentage (%) | Cumulative Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 12 | 14 | 9.2 | 10.9 | 10.9 |

| Certificate | 2 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 12.5 |

| Diploma | 21 | 13.8 | 16.4 | 28.9 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 66 | 43.4 | 51.6 | 80.5 |

| Master’s degree | 19 | 12.5 | 14.8 | 95.3 |

| Doctoral degree | 6 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 100 |

| Total | 128 | 84.2 | 100 |

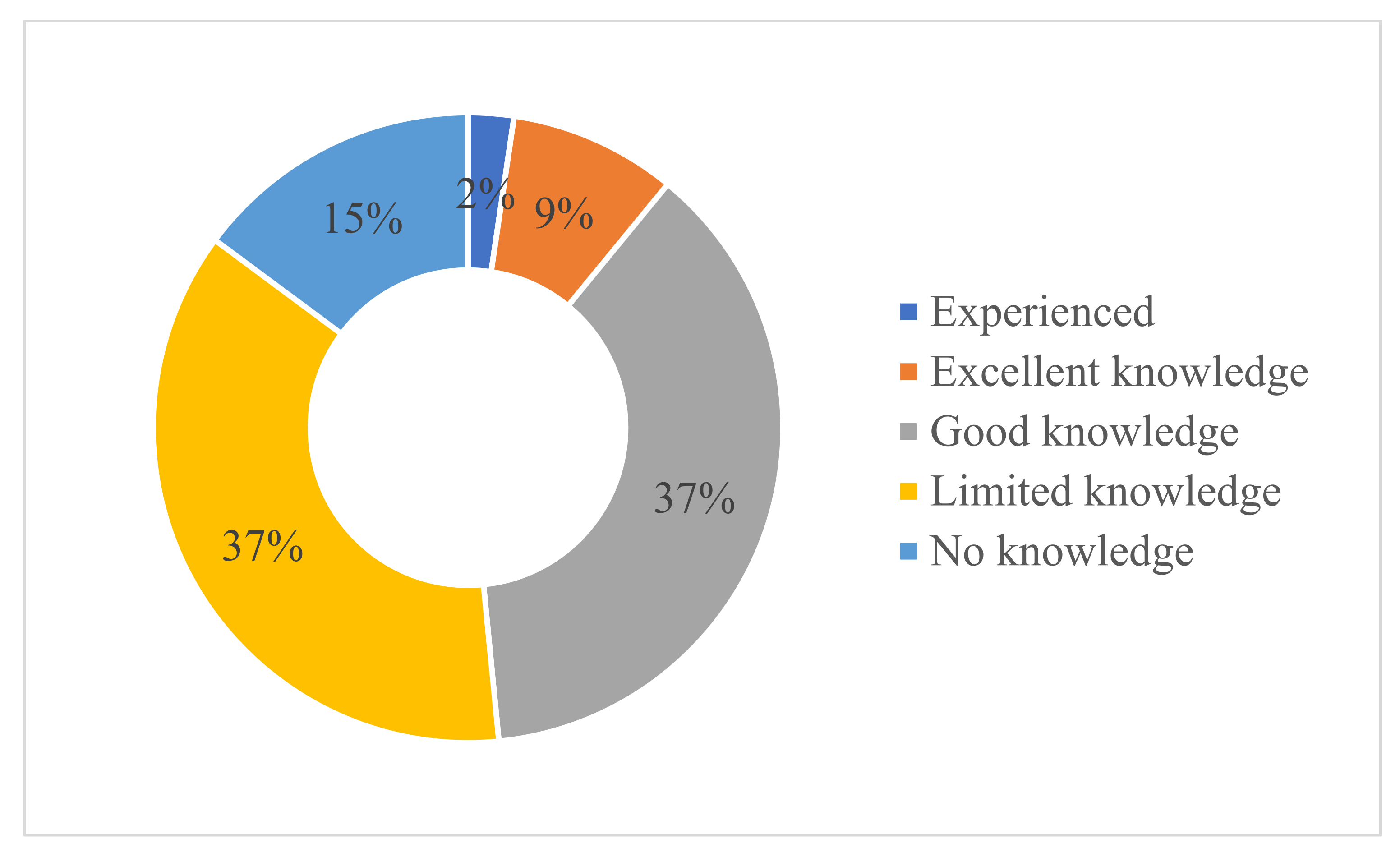

| Knowledge about Climate Change Policy Instruments | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Experienced | 3 | 2 |

| Excellent knowledge | 11 | 9 |

| Good knowledge | 48 | 38 |

| Limited knowledge | 47 | 37 |

| No knowledge | 19 | 15 |

| TOTAL | 128 | 100 |

| Policy Instruments | Extremely Inactive | Very Inactive | Inactive | Not Sure | Active | Very Active | Extremely Active | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Namibia’s Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan | 4 (3.1%) | 11 (8.6%) | 29 (22.7%) | 50 (39.1%) | 27 (21.1%) | 6 (4.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | 128 (100) |

| National Policy on Climate Change for Namibia | 5 (3.9%) | 7 (5.5%) | 20 (15.6%) | 51 (39.8%) | 32 (25.0%) | 10 (7.8%) | 3 (2.3%) | 128 (100) |

| National Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development Policy | 5 (3.9%) | 9 (7.0%) | 22 (17.2%) | 38 (29.7%) | 45 (35.2%) | 8 (6.3%) | 1 (0.8%) | 128 (100) |

| The Nature Conservation Ordinance No. 4 of 1975 | 4 (3.1%) | 7 (5.5%) | 8 (6.3%) | 46 (35.9%) | 44 (34.4%) | 15 (11.7%) | 4 (3.1%) | 128 (100) |

| The Communal Land Reform Act | 3 (2.3%) | 7 (5.5%) | 14 (10.9%) | 36 (28.1%) | 47 (36.7%) | 18 (14.1%) | 3 (2.3%) | 128 (100) |

| Namibia National Forest Policy | 2 (1.6%) | 8 (6.3%) | 10 (7.8%) | 36 (28.1%) | 51 (39.8%) | 17 (13.3%) | 4 (3.1%) | 128 (100) |

| Forestry Strategic Plan | 4 (3.1%) | 5 (3.9%) | 15 (11.7%) | 57 (44.5%) | 36 (28.1%) | 7 (5.5%) | 4 (3.1%) | 128 (100) |

| The Forest Act | 2 (1.6%) | 5 (3.9%) | 9 (7.0%) | 43 (33.6%) | 45 (35.2%) | 21 (16.4%) | 3 (2.3%) | 128 (100) |

| Policy Instruments | Extremely Ineffective | Very Ineffective | Ineffective | Not Sure | Effective | Very Effective | Extremely Effective | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Namibia’s Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan | 4 (3.1%) | 5 (3.9%) | 23 (18.0%) | 51 (39.8%) | 37 (28.9%) | 5 (3.9%) | 3 (2.3%) | 128 (100) |

| National Policy on Climate Change for Namibia | 4 (3.1%) | 4 (3.1%) | 20 (15.6%) | 49 (38.3%) | 41 (32.0%) | 9 (7.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 128 (100) |

| National Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development Policy | 4 (3.1%) | 3 (2.3%) | 24 (18.8%) | 39 (30.5%) | 43 (33.6%) | 10 (7.8%) | 5 (3.9%) | 128 (100) |

| The Nature Conservation Ordinance No. 4 of 1975 | 4 (3.1%) | 5 (3.9%) | 14 (10.9%) | 41 (32.0%) | 44 (34.4%) | 16 (12.5%) | 4 (3.1%) | 128 (100) |

| The Communal Land Reform Act | 3 (2.3%) | 2 (1.6%) | 17 (13.3%) | 36 (28.1%) | 54 (42.2%) | 14 (10.9%) | 2 (1.6%) | 128 (100) |

| Namibia National Forest Policy | 3 (2.3%) | 2 (1.6%) | 14 (10.9%) | 53 (41.4%) | 35 (27.3%) | 18 (14.1%) | 3 (2.3%) | 128 (100) |

| Forestry Strategic Plan | 4 (3.1%) | 4 (3.1%) | 14 (10.9%) | 58 (45.3%) | 36 (28.1%) | 10 (7.8%) | 2 (1.6%) | 128 (100) |

| The Forest Act | 4 (3.1%) | 2 (1.6%) | 11 (8.6%) | 45 (35.2%) | 51 (39.8%) | 13 (10.2%) | 2 (1.6%) | 128 (100) |

| Strategies | Extremely Ineffective | Very Ineffective | Ineffective | Not Sure | Effective | Very Effective | Extremely Effective | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimizing deforestation | 5 (3.9%) | 8 (6.3%) | 38 (29.7%) | 35 (27.3%) | 31 (24.2%) | 8 (6.3%) | 3 (2.3%) | 128 (100) |

| Promoting tree planting | 4 (3.1%) | 8 (6.3%) | 31 (24.2%) | 33 (25.8%) | 29 (22.7%) | 17 (13.3% | 6 (4.7%) | 128 (100) |

| Promoting agroforestry | 4 (3.1%) | 5 (3.9%) | 36 (28.1%) | 36 (28.1%) | 35 (27.3%) | 8 (6.3%) | 4 (3.1%) | 128 (100) |

| Reducing reliance on firewood as a source of energy | 10 (7.8%) | 11 (8.6%) | 53 (41.4%) | 23 (18.0%) | 21 (16.4%) | 7 (5.5%) | 3 (2.3%) | 128 (100) |

| Promoting alternative building materials | 8 (6.3%) | 3 (2.3%) | 30 (23.4%) | 32 (25.0%) | 36 (28.1%) | 16 (12.5%) | 3 (2.3%) | 128 (100) |

| Awareness creation in climate change and forest ecosystem services | 6 (4.7%) | 7 (5.5%) | 22 (17.2%) | 32 (25.0%) | 45 (35.2%) | 12 (9.4%) | 4 (3.1%) | 128 (100) |

| Research, development, and innovation | 5 (3.9%) | 2 (1.6%) | 36 (28.1%) | 35 (27.3%) | 39 (30.5%) | 8 (6.3%) | 3 (2.3%) | 128 (100) |

| Challenges | Extremely Insignificant | Very Insignificant | Insignificant | Not Sure | Significant | Very Significant | Extremely Significant | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harsh and dry climatic conditions | 4 (3.1%) | 5 (3.9%) | 10 (7.8%) | 36 (28.1%) | 37 (28.9%) | 28 (21.9%) | 8 (6.3%) | 128 (100) |

| High unemployment rates and poverty exert pressure on forest ecosystems | 5 (3.9%) | 8 (6.3%) | 12 (9.4%) | 18 (14.1%) | 28 (21.9%) | 34 (26.6%) | 23 (18.0%) | 128 (100) |

| High demands for grazing land | 4 (3.1%) | 4 (3.1%) | 5 (3.9%) | 19 (14.8%) | 41 (32.0%) | 29 (22.7%) | 26 (20.3%) | 128 (100) |

| Low awareness about the impacts of climate change among local communities | 5 (3.9%) | 5 (3.9%) | 15 (11.7%) | 31 (24.2%) | 34 (26.6%) | 26 (20.3%) | 12 (9.4%) | 128 (100) |

| Limited research and poor information dissemination | 5 (3.9%) | 6 (4.7%) | 9 (7.0%) | 26 (20.3%) | 30 (23.4%) | 38 (29.7%) | 14 (10.9%) | 128 (100) |

| Lack of funds for climate change mitigation and adaptation measures | 9 (7.0%) | 6 (4.7%) | 4 (3.1%) | 22 (17.2%) | 30 (23.4%) | 40 (31.3%) | 17 (13.3%) | 128 (100) |

| Limited law enforcement officials due to low government budget | 6 (4.7%) | 3 (2.3%) | 15 (11.7%) | 22 (17.2%) | 23 (18.0%) | 38 (29.7%) | 21 (16.4%) | 128 (100) |

| Recommendations | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness creation & public education | 80 | 43% |

| Fund for adaptation & mitigation | 26 | 14% |

| Rural communities’ participatory approach | 13 | 7% |

| Research & development | 13 | 7% |

| Active stakeholders’ participation | 11 | 6% |

| Review of policy instruments | 8 | 4% |

| Alternative building materials | 8 | 4% |

| Law enforcement | 7 | 4% |

| Afforestation & reforestation | 6 | 3% |

| Climate change in basic education | 5 | 3% |

| Minimize land clearing for agriculture | 3 | 2% |

| Improve implementation | 3 | 2% |

| Monitoring & evaluation | 2 | 1% |

| Total | 185 | 100% |

References

- ORC. Profile of Omusati Region. Outapi: Omusati Regional Council; Omusati Regional Council: Outapi, Namibia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Haukongo, C. An Assessment of Determinants of Adaptive Capacity of Livestock Farmers to Climate Change in Omusati Region, a Case of Onesi Constituency. In Proceedings of the 5th International Climate Change Adaptation Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 18–21 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Keskitalo, E.; Juhola, S.; Baron, N.; Fyhn, H.; Klein, J. Implementing Local Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Actions: The Role of Various Policy Instruments in a Multi-Level Governance Context. Climate 2016, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikodemus, A.; Hájek, M. Namibia’s National Forest Policy on Rural Development—A Case Study of Uukolonkadhi Community Forest. Agric. Trop. Subtrop. 2015, 48, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabcová, P.; Nikodemus, A.; Hájek, M. Utilization of Forest Resources and Socio-Economic Development in Uukolonkadhi Community Forest of Namibia. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2019, 67, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korir, J.C. Level of Awareness about Climate Change among the Pastoral Community. Environ. Ecol. Res. 2019, 7, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibiya, N.; Sithole, M.; Mudau, L.; Simatele, M.D. Empowering the Voiceless: Securing the Participation of Marginalised Groups in Climate Change Governance in South Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, P.; Al-Saidi, M. Local Community Perception of Climate Change Adaptation in Egypt. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 191, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Iyer, S.; New, M.G.; Few, R.; Kuchimanchi, B.; Segnon, A.C.; Morchain, D. Interrogating ‘Effectiveness’ in Climate Change Adaptation: 11 Guiding Principles for Adaptation Research and Practice. Clim. Dev. 2021, 14, 650–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Paris Agreement; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yazykova, S.; Bruch, C. Incorporating Climate Change Adaptation Into Framework Environmental Laws. Environ. Law Inst. 2018, 48, 10334. [Google Scholar]

- England, M.I.; Dougill, A.J.; Stringer, L.C.; Vincent, K.E.; Pardoe, J.; Kalaba, F.K.; Mkwambisi, D.D.; Namaganda, E.; Afionis, S. Climate Change Adaptation and Cross-Sectoral Policy Coherence in Southern Africa. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 18, 2059–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D. Prioritizing Climate Change Adaptation and Local Level Resilience in Durban, South Africa. Environ. Urban. 2010, 22, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Law and Policy in Namibia: Towards Making Africa the Tree of Life, 3rd ed; Ruppel, O.C., Ruppel-Schlichting, K., Eds.; Fully Revised and Updated; Hanns Seidel Foundation: Klein-Windhoek, Namibia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment and Tourism. National Policy on Climate Change for Namibia; Ministry of Environment and Tourism: Windhoek, Namibia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ulibarri, N.; Ajibade, I.; Galappaththi, E.K.; Joe, E.T.; Lesnikowski, A.; Mach, K.J.; Musah-Surugu, J.I.; Nagle Alverio, G.; Segnon, A.C.; Siders, A.R.; et al. A Global Assessment of Policy Tools to Support Climate Adaptation. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chersich, M.F.; Wright, C.Y. Climate Change Adaptation in South Africa: A Case Study on the Role of the Health Sector. Glob. Health 2019, 15, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsham, A.J.; Thomas, D.S.G. Knowing, Farming and Climate Change Adaptation in North-Central Namibia. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amesho, K.T.T.; Edoun, E.I.; Iikela, S.; Kadhila, T.; Nangombe, L.R. Absorbed Power Density Approach for Optimal Design of Heaving Point Absorber Wave Energy Converter: A Case Study of Durban Sea Characteristics. J. Energy S. Afr. 2022, 33, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keja-Kaereho, C.; Faculty of Economics and Management Sciences, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia; Tjizu, B.R.; Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia. Climate Change and Global Warming in Namibia: Environmental Disasters vs. Human Life and the Economy. Manag. Econ. Res. J. 2019, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapuka, A.; Hlásny, T. Social Vulnerability to Natural Hazards in Namibia: A District-Based Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingate, V.R.; Kuhn, N.J.; Phinn, S.R.; van der Waal, C. Mapping Trends in Woody Cover throughout Namibian Savanna with MODIS Seasonal Phenological Metrics and Field Inventory Data; Preprint; Biodiversity and Ecosystem Function: Basel, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendelvo, S.N.; Angula, M.; Mogotsi, I.; Aribeb, K. Towards the Reduction of Vulnerabilities and Risks of Climate Change in the Community-Based Tourism, Namibia. In Natural Hazards—Risk Assessment and Vulnerability Reduction; Simão Antunes do Carmo, J., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, D.; Chappel, A. Livelihoods on the Edge without a Safety Net: The Case of Smallholder Crop Farming in North-Central Namibia. Land 2018, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, S.; Davis, C.; Archer van Garderen, E. Forests, Rangelands and Climate Change in Southern Africa; Forests and Climate Change Working Paper, No. 12; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Musvoto, C.; Mapaure, I.; Gondo, T.; Ndeinoma, A.; Mujawo, T. Reality and Preferences in Community Mopane (Colophospermum Mopane) Woodland Management in Zimbabwe and Namibia. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2007, 1, 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, H.; Sahlén, L.; Stage, J.; MacGregor, J. The Economic Impact of Climate Change in Namibia: How Climate Change will Affect the Contribution of Namibia’s Natural Resources to its Economy; Environmental Economics Programme Discussion Paper 07-02; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Simataa, A.; Simataa, E. Namibian Multilingualism and Sustainable Development. JULACE J. Univ. Namib. Lang. Cent. 2017, 2, 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. Climate Risk Country Profile: Namibia; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; p. 20433. [Google Scholar]

- Krug, J.H.A. Adaptation of Colophospermum mopane to Extra-Seasonal Drought Conditions: Site-Vegetation Relations in Dry-Deciduous Forests of Zambezi Region (Namibia). For. Ecosyst. 2017, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhado, R.A.; Mapaure, I.; Potgieter, M.J.; Luus-Powell, W.J.; Saidi, A.T. Factors Influencing the Adaptation and Distribution of Colophospermum Mopane in Southern Africa’s Mopane Savannas—A Review. Bothalia 2014, 44, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.M.; Dinerstein, E.; Wikramanayake, E.D.; Burgess, N.D.; Powell, G.V.N.; Underwood, E.C.; D’amico, J.A.; Itoua, I.; Strand, H.E.; Morrison, J.C.; et al. Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth. BioScience 2001, 51, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, J.; Eriksson, H.; Heidecke, C.; Kellomäki, S.; Köhl, M.; Lindner, M.; Saikkonen, K. Socio-Economic Impacts—Forestry and Agriculture. In Second Assessment of Climate Change for the Baltic Sea Basin; The BACC II Author Team, Ed.; Regional Climate Studies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshirogi, K.; Yamashina, C.; Fujioka, Y. Variations in Mopane Vegetation and Its Use by Local People: Comparison of Four Sites in Northern Namibia. Afr. Study Monogr. 2017, 38, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppel, O.C.; Ruppel-Schlichting, K. (Eds.) Environmental Law and Policy in Namibia: Towards Making Africa the Tree of Life; Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft Mbh & Co.: KG Baden-Baden, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.; Silva, J.A. Climate Change and Poverty: Vulnerability, Impacts, and Alleviation Strategies. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, P.; Alavalapati, J.R.R.; Mercer, E.D. Socio-Economic Impacts of Climate Change on Rural United States. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2011, 16, 819–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunene Regional Council. Kunene Regional Development Profile 2015; The Ultimate Frontier: Windhoek, Namibia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lubinda, M. Factsheet: Climate Change The Definition, Causes, Effects, and Responses in Namibia. Desert Res. Found. Namib. 2015. Available online: www.enviro-awareness.org.na (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism. Republic of Namibia: First Adaptation Communication: Namibia’s Climate Change Adaptation Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC); Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism: Windhoek, Namibia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Muktadir, M.G. SPSS: An Imperative Quantitative Data Analysis Tool for Social Science Research. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2021, 5, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. Thematic Content Analysis (TCA): Descriptive Presentation of Qualitative Data. Inst. Transpers. Psychol. 2004, 32, 307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic Analysis of Qualitative Data: AMEE Guide No 131. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinstein, N.W.; Mach, K.J. Three Roles for Education in Climate Change Adaptation. Clim. Policy 2020, 20, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, E.N.; Hobbs, R.J.; Tsvuura, Z. No Safety Net in the Face of Climate Change: The Case of Pastoralists in Kunene Region, Namibia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Environment and Tourism. National Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan; Ministry of Environment and Tourism: Windhoek, Namibia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, M.; Schaap, B. Background Analytical Study 1: Forest Ecosystem Services. For. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 5, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Mupambwa, H.A.; Hausiku, M.K.; Nciizah, A.D.; Dube, E. The Unique Namib Desert-Coastal Region and Its Opportunities for Climate Smart Agriculture: A Review. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1645258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikangalah, R.N. The 2019 Drought in Namibia: An Overview. J. Namib. Stud. 2020, 27, 37–58. [Google Scholar]

| Policy Instruments | Extremely Inactive | Very Inactive | Inactive | Not Sure | Active | Very Active | Extremely Active | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Namibia’s Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan | 4 (3%) | 11 (9%) | 29 (23%) | 50 (39%) | 27 (21%) | 6 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 128 (100) |

| National Policy on Climate Change for Namibia | 5 (4%) | 7 (6%) | 20 (16%) | 51 (38%) | 32 (25%) | 10 (8%) | 3 (2%) | 128 (100) |

| National Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development Policy | 5 (4%) | 9 (7%) | 22 (17%) | 38 (30%) | 45 (35%) | 8 (6%) | 1 (1%) | 128 (100) |

| The Nature Conservation Ordinance No. 4 of 1975 | 4 (3%) | 7 (6%) | 8 (6%) | 46 (36%) | 44 (34%) | 15 (12%) | 4 (3%) | 128 (100) |

| The Communal Land Reform Act | 3 (2%) | 7 (6%) | 14 (11%) | 36 (28%) | 47 (37%) | 18 (14%) | 3 (2%) | 128 (100) |

| Namibia National Forest Policy | 2 (2%) | 8 (6%) | 10 (8%) | 36 (28%) | 51 (40%) | 17 (13%) | 4 (3%) | 128 (100) |

| Forestry Strategic Plan | 4 (3%) | 5 (4%) | 15 (12%) | 57 (45%) | 36 (28%) | 7 (6%) | 4 (3%) | 128 (100) |

| The Forest Act | 2 (2%) | 5 (4%) | 9 (7%) | 43 (34%) | 45 (35%) | 21 (16%) | 3 (2%) | 128 (100) |

| Policy Instruments | Extremely Ineffective | Very Ineffective | Ineffective | Not sure | Effective | Very Effective | Extremely Effective | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Namibia’s Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan | 4 (3%) | 5 (4%) | 23 (18%) | 51 (40%) | 37 (29%) | 5 (4%) | 3 (2%) | 128 (100) |

| National Policy on Climate Change for Namibia | 4 (3%) | 4 (3%) | 20 (16%) | 49 (38%) | 41 (32%) | 9 (7%) | 1 (1%) | 128 (100) |

| National Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development Policy | 4 (3.1%) | 3 (2%) | 24 (19%) | 39 (31%) | 43 (34%) | 10 (8%) | 5 (4%) | 128 (100) |

| The Nature Conservation Ordinance No. 4 of 1975 | 4 (3%) | 5 (4%) | 14 (11%) | 41 (32%) | 44 (34%) | 16 (13%) | 4 (3%) | 128 (100) |

| The Communal Land Reform Act | 3 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 17 (13%) | 36 (28%) | 54 (42%) | 14 (11%) | 2 (2%) | 128 (100) |

| Namibia National Forest Policy | 3 (2.3%) | 2 (2%) | 14 (11%) | 53 (41%) | 35 (27%) | 18 (14%) | 3 (2%) | 128 (100) |

| Forestry Strategic Plan | 4 (3%) | 4 (3%) | 14 (11%) | 58 (45%) | 36 (28%) | 10 (8%) | 2 (2%) | 128 (100) |

| The Forest Act | 4 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 11 (9%) | 45 (35%) | 51 (40%) | 13 (10%) | 2 (2%) | 128 (100) |

| Extremely Ineffective | Extremely Ineffective | Very Ineffective | Ineffective | Not Sure | Effective | Very Effective | Extremely Effective | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimizing deforestation | 5 (4%) | 8 (6%) | 38 (28%) | 35 (27%) | 31 (24%) | 8 (6%) | 3 (2%) | 128 (100) |

| Promoting tree planting | 4 (3%) | 8 (6%) | 31 (24%) | 33 (26%) | 29 (23%) | 17 (13%) | 6 (5%) | 128 (100) |

| Promoting agroforestry | 4 (3%) | 5 (4%) | 36 (28%) | 36 (28%) | 35 (27%) | 8 (6%) | 4 (3%) | 128 (100) |

| Reducing reliance on firewood for energy | 10 (8%) | 11 (9%) | 53 (41%) | 23 (18%) | 21 (16%) | 7 (6%) | 3 (2%) | 128 (100) |

| Promoting the use of alternative building materials | 8 (6%) | 3 (2%) | 30 (23%) | 32 (25%) | 36 (28%) | 16 (13%) | 3 (2%) | 128 (100) |

| Awareness creation in climate change and forest ecosystem services | 6 (5%) | 7 (6%) | 22 (17%) | 32 (25%) | 45 (35%) | 12 (9%) | 4 (3%) | 128 (100) |

| Research, development, and innovation | 5 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 36 (28%) | 35 (27%) | 39 (31%) | 8 (6%) | 3 (2%) | 128 (100) |

| Challenges | Extremely Insignificant | Very Insignificant | Insignificant | Not Sure | Significant | Very Significant | Extremely Significant | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry climatic conditions | 4 (3%) | 5 (4%) | 10 (8%) | 36 (28%) | 37 (29%) | 28 (22%) | 8 (6%) | 128 (100) |

| High unemployment rates and poverty exert pressure on forest ecosystems | 5 (4%) | 8 (6%) | 12 (10%) | 18 (14%) | 28 (22%) | 34 (27%) | 23 (18%) | 128 (100) |

| High demands for land for agricultural practices | 4 (3%) | 4 (3%) | 5 (4%) | 19 (15%) | 41 (32%) | 29 (23%) | 26 (20%) | 128 (100) |

| Inadequate awareness creation in rural communities | 5 (4%) | 5 (4%) | 15 (12%) | 31 (24%) | 34 (27%) | 26 (20%) | 12 (10%) | 128 (100) |

| Limited research and poor information dissemination | 5 (4%) | 6 (5%) | 9 (7%) | 26 (20%) | 30 (23%) | 38 (30%) | 14 (11%) | 128 (100) |

| Lack of funds for climate change adaptation measures | 9 (7%) | 6 (5%) | 4 (3%) | 22 (17%) | 30 (23%) | 40 (31%) | 17 (13%) | 128 (100) |

| Inadequate law enforcement officials due to low government budget | 6 (5%) | 3 (2%) | 15 (12%) | 22 (17%) | 23 (18%) | 38 (30%) | 21 (16%) | 128 (100) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nikodemus, A.; Hájek, M. Implementing Local Climate Change Adaptation Actions: The Role of Various Policy Instruments in Mopane (Colophospermum mopane) Woodlands, Northern Namibia. Forests 2022, 13, 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101682

Nikodemus A, Hájek M. Implementing Local Climate Change Adaptation Actions: The Role of Various Policy Instruments in Mopane (Colophospermum mopane) Woodlands, Northern Namibia. Forests. 2022; 13(10):1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101682

Chicago/Turabian StyleNikodemus, Andreas, and Miroslav Hájek. 2022. "Implementing Local Climate Change Adaptation Actions: The Role of Various Policy Instruments in Mopane (Colophospermum mopane) Woodlands, Northern Namibia" Forests 13, no. 10: 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101682

APA StyleNikodemus, A., & Hájek, M. (2022). Implementing Local Climate Change Adaptation Actions: The Role of Various Policy Instruments in Mopane (Colophospermum mopane) Woodlands, Northern Namibia. Forests, 13(10), 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101682