Abstract

The effective prevention and control of forest disasters is important for forest resources and the well-being of those living in forested areas. This study evaluates the impact of a policy that employs a rural impoverished population as ecological forest rangers (EFRs) for the incidence of forest disasters. We estimate a generalized difference in differences (DID) model using nationwide provincial-level forest disaster data combined with regional data in all policy pilot areas. There are three primary findings. (1) The implementation of the EFR policy failed to effectively reduce the incidence of forest fires, forest pests, forest diseases, forest rodents and other forest disasters, which shows that the EFR policy has not achieved the goal of “forest protection”. (2) The effect of the EFR policy on forest disaster control is not significantly different among provinces with different forest resource endowments and different levels of social and economic development. This shows that there is no significant difference in the implementation of EFR policies between different forest resource endowments and different socioeconomic development areas. (3) The EFR policy failed to achieve the effective coordination of the dual goals of “poverty reduction” and “ecological protection”; this is the main reason for the failure to reduce the incidence of forest disasters while reducing poverty. The pressure of this policy neglected the “forest management and protection” function of the policy and the corresponding assessment requirements. At the same time, the central government also neglected the assessment of the prevention and control of “forest disasters” by local governments when implementing this policy. Ultimately, the opportunism of local governments and ecological rangers was strengthened. Therefore, the goals of environmental service payment items and the corresponding evaluation index settings need to be matched to truly achieve the established goals.

1. Introduction

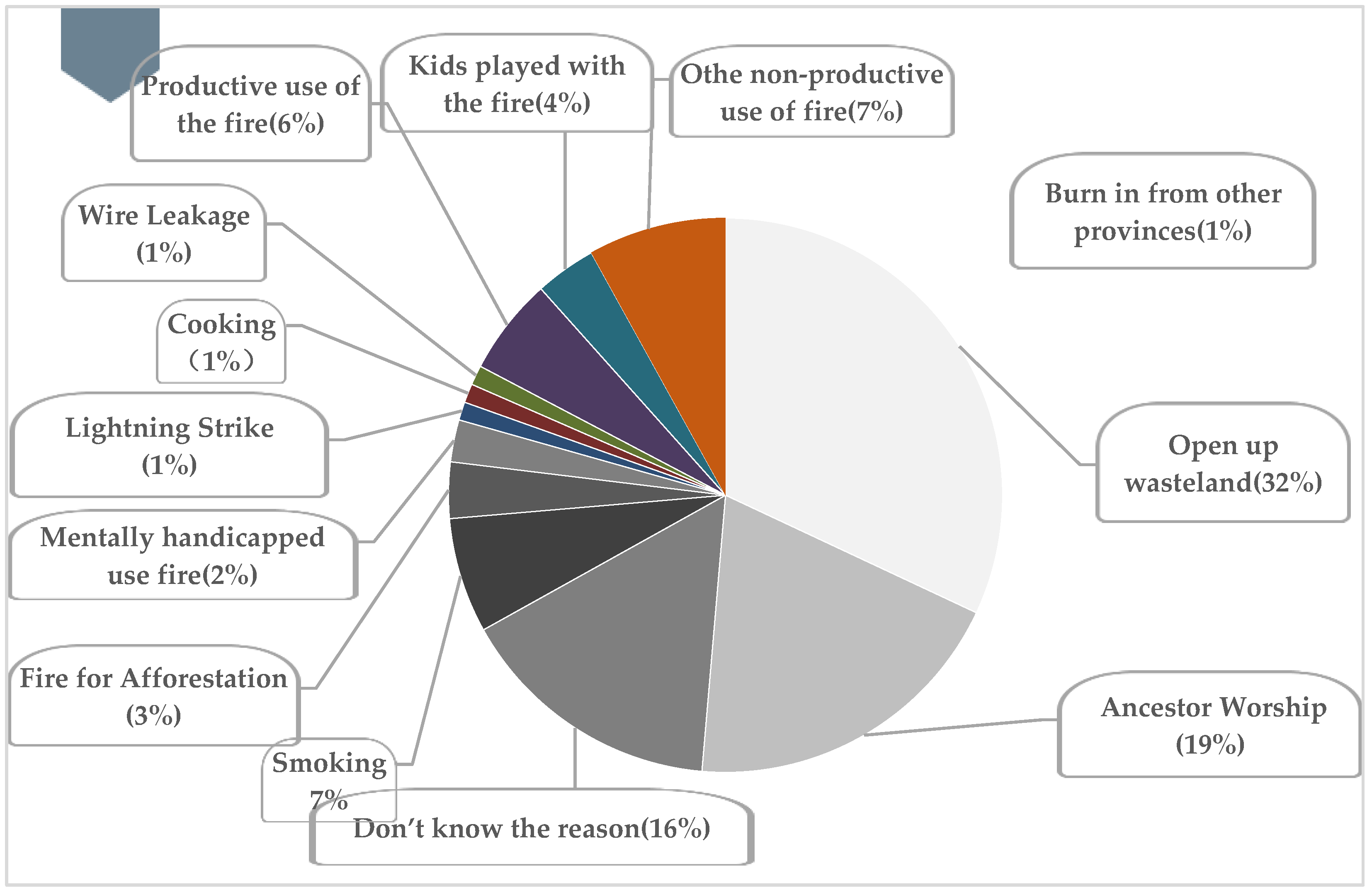

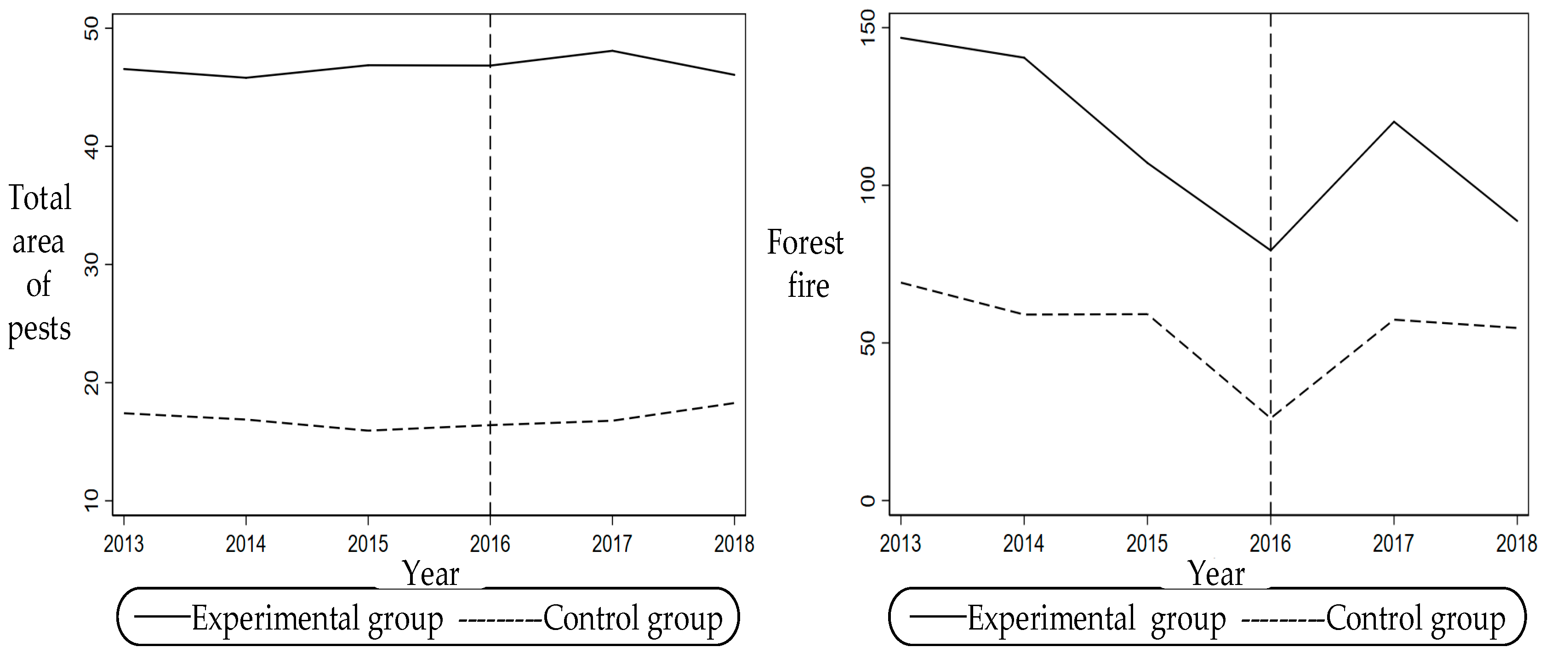

Forests are the main component of terrestrial ecosystems, and the ecological characteristics of forests in a given country or region determine its corresponding ecological security status [1]. Forest disasters, dominated by forest fires, pests, diseases and rodents have significant negative impacts on the livelihoods of people and the safety of their property, the protection of biodiversity, and the stable development of agriculture, forestry and animal husbandry [1,2,3]. Therefore, strengthening the management of forest disasters and effectively reducing the incidence of forest disasters are not only important components of global forest management and construction, but also strongly guarantee that land and space management are strengthened and that the value of ecological resources is realized. Forest management also facilitates the maintenance of biodiversity and the protection of ecosystems, strongly guaranteeing their integrity. Numerous studies indicated that forest disasters, especially forest fires and forest pests, are caused by anthropogenic activities or anthropogenic management negligence in most cases [4,5], and that high-incidence areas and forest resource-rich areas overlap with each other [6]. Taking forest fires in China as an example, we obtained statistics from the China Forestry Statistical Yearbook (2004–2016). A total of 82.5% of forest fires were caused by anthropogenic activities, and only 1.3% of forest fires were instigated by natural causes. In addition, the causes of 15.2% of forest fires were unknown, while the other 1% of forest fires were caused by external burning (see Appendix A 1.1; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of forest fire causes in China from 2004 to 2016.

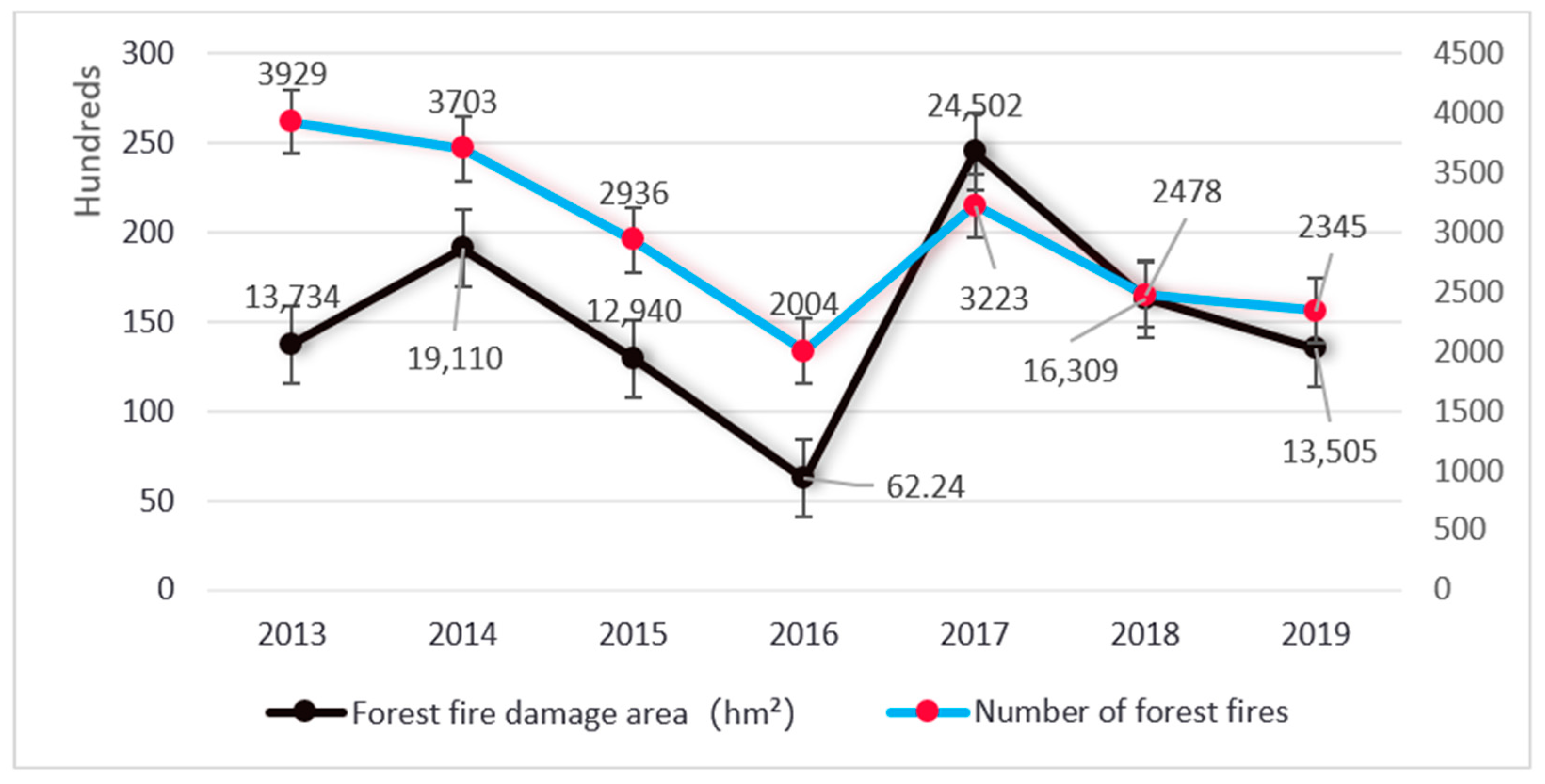

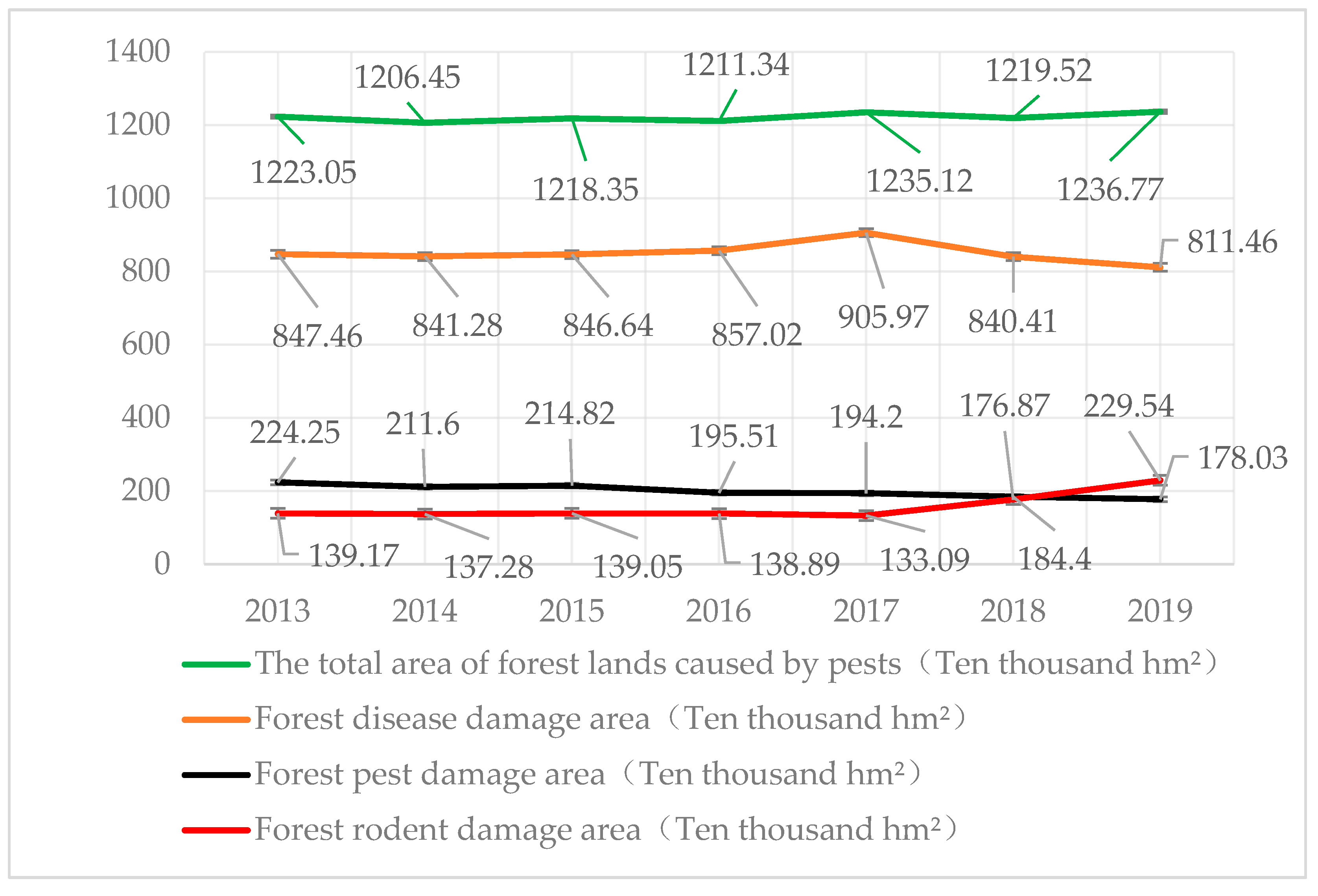

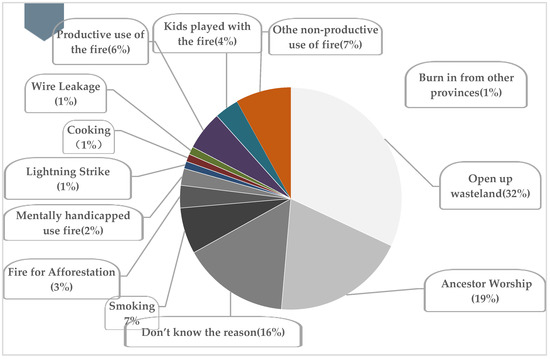

The above illustration suggests that strengthening the use of fire in the production and livelihood activities of forest residents can effectively reduce the incidence of forest fires. In addition, forest disasters associated with many forest pests, diseases and rodents mainly lack effective early warning mechanisms. Therefore, reducing the incidence of forest disasters through external monitoring mechanisms is an important governance method. After 1978, a collective forest tenure reform enacted in China based on the household contract responsibility system greatly increased the investment of Chinese farmers’ families in the management and protection of forest resources by significantly reducing forest fires, forest diseases, insect pests and other forest disasters in China [7]. However, due to the incomplete property rights associated with China’s forestland, the outflow of forest sector labor force, and the relatively low proportion of forestry income, many “unmanaged public zones” exist when considering the management and protection of forest resources in China’s collective forest areas, especially forest disasters, wild animal and plant resources, and other novel factors. Public infrastructure and other construction activities have not been effectively managed for a long time, causing the “tragedy of the commons” in collective forest areas. As a result, the incidence of forest disasters in China is still relatively high, and the incidence rate shows great year-to-year fluctuations, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Yearly changes in the area and number of forest fires in China (2013–2019).

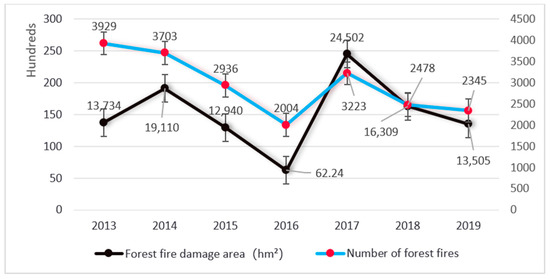

Figure 3.

Yearly changes in the area affected by pests in China (2013–2019).

The policy of ecological forest rangers (EFRs) was formulated by China for impoverished populations based on the characteristics of the high overlap between the impoverished populations and the geographical distribution of forest resources and the need for poverty alleviation strategies. The main goal of this policy was to implement effective forest disaster monitoring through the patrolling and protection of forests by employing the labor of impoverished people living in vast collective forest areas or grasslands and some state-owned forest areas, as facilitated through the direct purchase of ecological services by the government. The dual goals of this policy included poverty reduction and ecological protection. As of now, this policy has been implemented in 23 provinces or autonomous regions in China. At the end of 2019, a total of USD 2.19 billion from central government finances and USD 0.42 billion from provincial finances were allocated to recruit EFRs among impoverished populations, and ecological forest protection goals were accumulatively identified. More than 1 million people are employed as EFRs (see Appendix A 1.2). Although the main goals of this policy were to achieve “poverty reduction” and “protect ecosystems”, in the policy implementation process, too many impoverished people were employed with low human capital, and the higher-level government management department also considered whether the policy employed impoverished populations and achieved the goal of poverty reduction during its assessment. The labor subsidy standards for ecological forest rangers essentially reached the state of “selecting and hiring to get rid of poverty” (see Appendix A 1.3). Therefore, the poverty reduction effect of the policy was very clear, effectively achieving “poverty alleviation by selection”; however, for the ecological protection effect of the policy, especially regarding the mitigation of forest fires, diseases and insect pests and other forest disasters within the scope of forest rangers’ duties, the results obtained when judging whether forest ecology protection was achieved are extremely vague.

Then, under the mobilization of such large-scale human, material and financial resources, whether the EFR policy can effectively reduce the incidence of forest disasters and achieve better forest resource management and protection has become an important practical problem that urgently needs to be studied. Based on this issue, this article applied statistical data gathered at the provincial level in China and the difference in differences (DID) model to evaluate the impacts of the EFR policy on forest disasters from the perspective of forest fires and forest pests. Studying the ecological effects of this policy can provide a realistic reference for the formulation, improvement and implementation of this policy and other environmental service payment policies. Compared to previous studies, the marginal contributions of our paper may include the following: first, in this study, relatively scientific policy evaluation methods and comprehensive statistical data are used to assess the impacts of the EFR policy on forest disasters; second, from the type and level of forest disasters, and from the perspective of resource stocks and regional differences, the differential impacts of the EFR policy on forest disasters were evaluated; and third, empirical observations obtained in China’s Sichuan Province were used to verify the reasons or mechanisms behind the policy’s reported effects.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Current Status of Research on Environmental Payment Project Policy Effects

Ecological compensation projects are collectively referred to as payments for environmental services (PES) internationally. This type of policy originated in Costa Rica in 1997; since then, the specific contents of these policies and their systematic designs have expanded widely, and today, these policies cover water, biological diversity, carbon dioxide, soil, forests and other ecosystems. From the perspective of global practical experience, due to the high degree of overlap between forest resources and impoverished populations [8], many countries implemented PES projects in poverty-stricken areas to achieve the dual goals of “poverty reduction and environmental protection” [9,10,11,12]. According to existing research, previous researchers’ assessments of the ecological effects of “payment for environmental services” projects focused on forest resources mainly considered the perspectives of biodiversity and forest resource stocks; their main conclusions indicated that subsidy-based environmental service projects associated with ecological compensation, afforestation or forest tending had a significant positive impact on biodiversity and forest resource accumulation [9,11,13,14].

However, the empirical results of some researchers indicated that PES projects may not necessarily achieve ecological protection effects. For example, some researchers pointed out that, when the agents implementing the PES project have expectations of potential future subsidies, moral hazards arise, and PES plans may then provide limited additional environmental benefits [15]. On the other hand, the background of special political, economic and social conditions may exacerbate power and wealth asymmetries when PES projects are implemented [16,17], and payment methods, communication, remuneration, inclusive and participatory decision-making, and monitoring and sanctioning procedures may affect the enthusiasm of participants and, ultimately, the effects of the project implementation [18]. Therefore, in ecological compensation policies, problems arise that are associated with targeting and matching positions, abilities, and funds [19]; the heterogeneity of farmers also needs to be considered [20,21], and compensation mechanisms must be carefully designed to meet both ecological protection and poverty alleviation goals [22].

2.2. The Current Research Situation Regarding the Effects of EFR Policies

Regarding the evaluation of EFR policies, some researchers used statistical data and provincial experience to observe and analyze the effective reduction in forest disasters, such as forest fires and pests, following the implementation of EFR policies, thus achieving the “poverty reduction and ecological management” goal, a win–win situation [23,24,25]. However, some researchers pointed out that these policies are essentially “temporary employment assistance policies”, and the main goal of these policies is poverty reduction [26]. Some researchers applied data characterizing impoverished ecological forest rangers in Sichuan Province to analyze ecological forest protection enacted by the impoverished population. They followed the re-employment behavior of the poor population and found that, in the re-employment of EFRs, more emphasis was placed on poverty indicators while the human capital indicators associated with management and protection personnel was neglected [12]. The abovementioned differences indicate that the impacts of EFR policies on forest disasters are uncertain.

Through the above literature review, we found that the existing literature mainly focused on evaluating the performances of PES projects, while mainly considering the perspectives of biodiversity and forest resource stocks; the existing research lacks the perspective of disaster incidence rates when evaluating the ecological effects of ecological compensation policies. In addition, when evaluating the effects of EFR policies, only analyses of individual cases and perceptual knowledge were conducted, while no effective empirical test was created.

3. Policy Background and Hypothesis

3.1. Policy Background

Since the “Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Winning the Poverty Alleviation War” in November 2015, the “Poverty Alleviation War” was formally proposed; since this time, governments at all levels in China have closely focused on the “poverty reduction” goal, and associated policies have been fully implemented. “China’s Rural Poverty Alleviation and Development Program (2011–2020)” (see Appendix A 1.4) and the 2015 “Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Winning the Fight against Poverty” (see Appendix A 1.5) were established, focusing on the use of ecological compensation and ecological protection project funds to convert part of the local population with labor abilities into forest rangers and other ecological protection personnel. These policies were generated under the requirements of “personnel”, an important measure in the “eight batches” of ecological compensation for poverty alleviation.

In September 2016, the State Forestry Administration (now the Forestry and Grassland Administration) and the Ministry of Finance and the Poverty Alleviation Office of the State Council jointly issued the “Notice on Carrying out the Selection and Employment of Ecological Forest Rangers for the impoverished population” (see Appendix A 1.6). This policy focused on centralized contiguous special poverty-stricken areas to ensure national poverty alleviation and the development of key counties and key ecological functional zones through transfer payments comprehensively implemented to conduct the selection and employment of EFRs among impoverished people on file. Most forest rangers were selected and hired by late October.

It should be noted that, according to the latest revision of the Land Management Law (see Appendix A 1.7) in 2020, China’s forest land property rights are divided into state ownership and village collective ownership, but the wild animals, minerals, and infrastructure in village collective forest land are also owned by the state. Among them, the state-owned part has professional forestry staff management and protection, while the village collective forest land is managed only by the farmers themselves, which means that the village collective forest land is under effective management and protection. Therefore, the ecological forest rangers employed by the EFR policy manage and protect the forest land owned by the village collectives.

In 2017, the Department of Forestry of Anhui Province took the lead in promulgating the “Administrative Measures for Ecological Rangers of the Impoverished Population in Anhui Province (Trial)”, the embryonic form of the EFR system framework (see Appendix A 1.8). In 2018, the Poverty Alleviation and Development Office of the State Council and the State Forestry and Grassland Administration jointly issued the “Administrative Measures for the Establishment of Ecological Forest Rangers for the impoverished population”, in which the concepts, responsibilities, selection, management, and subsidy standards of EFRs were reviewed. The design of this macro system clearly pointed out that the main duties of forest rangers included the prevention of forest fires, fires, and forestry pest hazards in their corresponding management and protection area, the reporting of these disasters in a timely manner, and taking effective measures to fight these disasters. In addition, the responsibilities of EFRs include the management and protection of resources such as animals, plants and public infrastructure in their corresponding management and protection zones (see Appendix A 1.9).

At present, the framework of the EFR system has been effectively established in major regions of China and is continuously improved and adjusted. Therefore, from the main responsibilities of EFRs, we can see that the emergence of forest rangers has established a “defensive wall” against the occurrence of forest disasters. One of the main goals of the EFR policy is to reduce the incidence of forest disasters in China.

3.2. Hypothesis

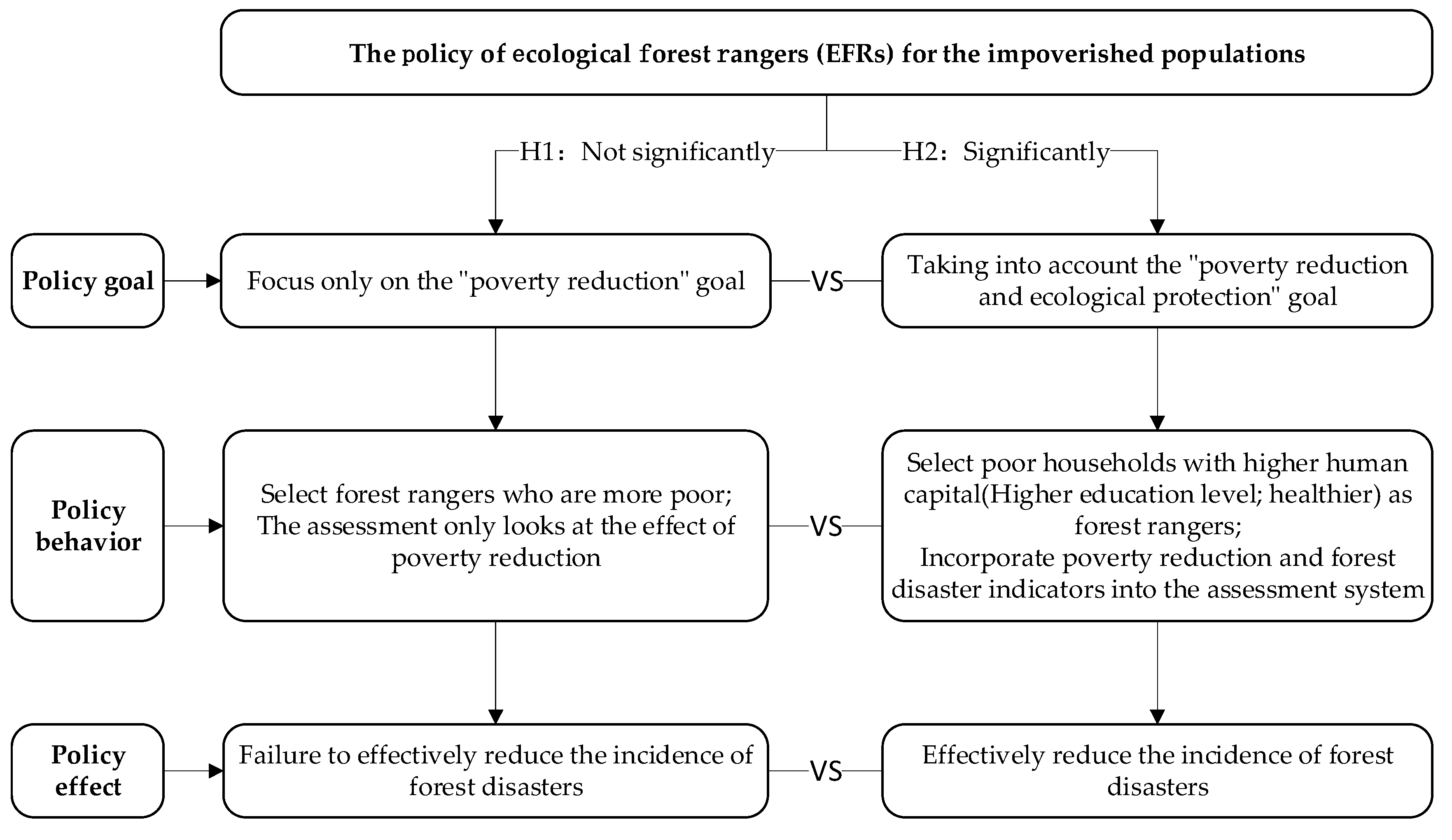

For public policies that take into account multiple goals, the policy executor’s choice of goals will affect the consequences of policy implementation. The local government selects policy objectives based on the constraints of higher-level evaluation, policy costs, practical needs, opportunism, etc. The local government will take the initiative to adopt corresponding policies, allowing the actions of other participants in the policy to match the selected policy objectives for consistency. For this phenomenon—researchers call it an “adaptive connection”, which is in the process of public policy implementation—the needs of the local government adjust according to the policy objectives, and each participant contributes to the policy implementation process in the policy resource allocation and performance. Consistency is reached in the content of assessment, implementation objects, and implementation methods [27]. Therefore, policy objectives and specific implementation behaviors are often complementary, especially under China’s special decentralization system, and the evaluation of lower-level government performances by higher-level governments directly affect the behaviors of local governments [28,29]. Political performance evaluations depend on a government’s chosen policy goals. Therefore, the effects of a given policy depend on the corresponding assessment constraints, and the design of these assessment constraints and the selected assessment system depend on the chosen policy objectives. When considering multiple policy goals that may conflict, the selection of different goals in the evaluation process affects the realization of the final policy effects.

To a certain extent, the dual EFR policy goals of “poverty reduction and ecological protection” are contradictory. The poverty reduction goal is mainly aimed at low-income groups, whose human capital levels are generally low. Specifically, this can be manifested as a low level of education, unhealthy body, lack of working ability, lack of initiative or creativity. However, ecological protection is a relatively professional job that not only requires professionalism but also demands a good physical strength to meet forest patrolling and protection needs. Ecological protection activities also require the ability of personnel to judge forest disasters and to deal with emergencies; these jobs can even require the courage to stop illegal or unethical behavior in the forest, yet impoverished people tend to lack the resources to perform such actions. In addition, the distribution and patrol areas of EFRs are mostly scattered in forest areas, and when considering village cadres or assessment departments such as township forestry stations, it is difficult to effectively supervise the management and protection of forest rangers. Due to supervision difficulties, these policies can very easily lead to “opportunism” behaviors in forest guards. According to the above logic, when conducting an analysis of policy effects, the causes of these effects can be explained by the orientation of the target in the implementation process.

From the perspective of the specific policy system design, two choices exist, corresponding to the policy goals. (1) In the first choice, the policy system focuses only on “poverty reduction”. Correspondingly, the policy does not consider the implementation level of the target’s ecological management or protection ability; it only selects the most impoverished groups and does not consider the implementation of regional forest disasters or ecological quality improvements in the assessment process. Since this policy only focuses on poverty reduction goals during the implementation of this policy, the assessment of local governments and ecological forest rangers was not included in the indicators of ecological protection. Therefore, this will greatly enhance the opportunism of local governments and ecological forest rangers. On the one hand, ecological forest rangers do not pay attention to the occurrence of forest disasters in the management and protection process because they are not restricted by the assessment of ecological indicators. On the other hand, because the local government does not have the pressure of forest management assessment, the policy will not be implemented to reduce the incidence of forest disasters during the implementation of the policy.

Under such target selection, due to forest disaster indicators being neglected in policy implementation targets and assessments, the policy cannot effectively reduce the incidence of forest disasters. (2) In the second choice, the policy system considers the balance of “poverty reduction and ecological protection”. The corresponding policy considers the ecological management and protection capabilities of the target during the implementation process and incorporates forest disaster indicators during the performance assessment process. Under this target selection framework, the ecological management of the implementation target is compacted. The implementation of this policy greatly reduces the incidence of forest disasters. The former goal is mainly reflected in the government’s urgent need to achieve short-term “poverty reduction”, while the latter is mainly reflected in the government’s urgent need to simultaneously promote poverty reduction and ecological protection. However, during the implementation of EFR policies, China’s government implemented poverty reduction as a political task. Therefore, it is very likely that “poverty reduction” is emphasized while “ecological protection” is neglected in the specific implementation process. As a result, these policies did not effectively reduce the incidence of forest disasters in China. Based on this, the relationship between EFR policies and the incidence of forest disasters may contribute to the two following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The EFR policy cannot significantly reduce the incidence of forest disasters.

Under this proposition, the goal of EFR policies is mainly to focus on the “poverty reduction” goal while ignoring the realization of the “ecological” goal; this hypothesis may be manifested in the following implementation process: (1) targets are mainly selected based on poverty indicators, while human capital indicators related to management and protection are ignored; (2) indicators related to “ecological protection” are reduced or even ignored in the performance appraisal process.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The EFR policy can significantly reduce the incidence of forest disasters.

Under this proposition, the EFR policy goals focus on the coordination of the dual goals of “poverty reduction and ecological protection”, and the corresponding implementation behaviors may be expressed as follows: first, the targets are selected from groups with high human capital among impoverished populations; and second, the ecological protection indicators are quantified or compacted in the performance appraisal process.

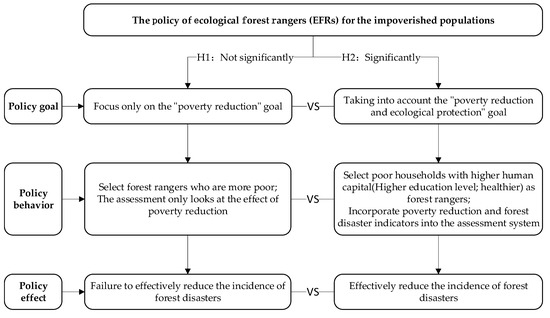

The specific logical relationship is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The logical relationship between the policy and the occurrence of forest disasters.

According to the logical relationship presented in Figure 4, we know that, if the EFR policy is only to achieve the policy goal of “poverty reduction”, then in the implementation of the policy, poor groups with low levels of human capital will be selected as the targets for hiring forest rangers, and the project will be used as much as possible. Funds hire more poor people as forest rangers to achieve the goal of “poverty reduction”. In addition, since the goal of the policy is to reduce poverty, forest rangers do not care about whether forest disasters can be reduced, and they do not care about forest disaster prevention and control indicators during the assessment. In contrast, if the EFR policy wants to achieve the coordination of the dual goals of “poverty reduction” and “ecological protection”, it must select a higher level of human capital among the policy-designated goals, and it will be related to the forest disaster prevention and control effect when the policy implementation effect is assessed.

4. Data and Model Design

4.1. Data

The dataset in this study was obtained from the Chinese National Statistical Yearbook from 2014 to 2019 in 31 provinces, which contains province-level forest diseases data and socio-economic data (see Appendix A 1.10). The basic geographic features of each province were manually extracted based on the introduction of the human geographic conditions of each province in the Baidu Encyclopedia. The forest disasters analyzed in this article mainly include forest fires and forest pests (specifically, diseases, pests, and rodents). The forest fire levels refer to the levels defined in the “China National Statistical Yearbook” (see Appendix B).

4.2. Model Design

In this study, 2016 was used as the implementation year, corresponding to the demarcation point separating the time periods before and after the EFR policy was implemented. This policy is an exogenous reform policy promoted by the national forestry and poverty alleviation departments from top to bottom, providing a realistic basis for this article to distinguish between an experimental group and a reference group. In this paper, the 23 provinces, in which the policy was implemented, were regarded as the “experimental group”, and the 8 provinces that did not implement the policy were regarded as the “reference group”. The DID method is widely used in public policy effect evaluations [30]; in this study, according to the DID method principles, the estimation model of this article is set as follows:

where Yit is the explained variable. It represents the number of forest disasters or the area affected in province in year . The variable is a dummy that indicates whether province i adopted the EFR policy during the period from 2014 to 2019. It takes the value of one if the province adopted the EFR policy and the province i is considered as a treatment group, otherwise it becomes the control group. The variable is a dummy that indicates the timing of pre-intervention or post-intervention. Then, the interaction term is province i’s treatment status equal to one for the year that province i implemented the EFR policy and the year for after. The EFR policy mainly strengthens the patrol of forests by hiring ecological forest rangers, especially requiring the monitoring of forest disasters such as forest fires, diseases, pests, and rodents. Therefore, when the EFR policy is implemented, the control of forest disasters in provinces where the policy is implemented is strengthened. If the implementation of the policy is effective, the same area where the policy is not implemented will significantly reduce the incidence of forest fires in the implementation area. In contrast, if the prevention and control of forest disasters were not considered during the implementation of the policy, there would be no significant difference in the incidence of forest disasters between the provinces that implemented the EFR policy and the provinces that did not implement the policy, as well as before the policy was implemented. The variable is the focus of this article and represents the marginal effect on the incidence of forest disasters after the implementation of the EFR policy. For example, if is a negative number and is significant when it returns, it means that the implementation of the EFR policy can significantly reduce the occurrence of forest disasters; is the intercept term; and is a series of other control factors that affect the occurrence of forest disasters. The variable represents the sum of the marginal contribution rates of other factors affecting the occurrence of forest disasters. We include both the province fixed effects () and year fixed effects () in order to control for time-invariant province characteristics and common time trends that affect all provinces in the same way; is the random error term.

4.3. Variable Selection and Definition

In this study, the explained variable, forest disasters, mainly involves forest fires and forest pests, and the control variables mainly include forest-disaster-influencing factors, selected in reference to Tao Qing et al. (2015) and Ying Zhang et al. (2015) [7,31]. The control variables were selected with respect to the importance of forestry resources, the economic and social development levels, human capital level, meteorological conditions, and informatization. The specific variable selection and setting values are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable meanings and assignment rules.

4.4. Methods

Since there are significantly differences between the treatment group that implemented the EFR policy and control group in the terms of socio-economic variables, and in the absence of a random control trial, the implementation of the EFR policy time may be correlated with some socio-economic variables, such as gross domestic product per capita, poverty incidence at the province level, which would lead to inconsistent estimates of the impact of the EFR policy on forestry diseases. Based on this, we adopt a generalized difference in differences (DID) approach to identify the causal effect of the EFR policy on forestry diseases, which can capture the time-variant unobservable variables that could confound the policy implementation.

Second, we aimed to understand whether the implementation effect of the policy would be affected by the endowment of forestry resources and the level of regional economic development. This is because areas with richer forest resources will employ more forest rangers, and the localities will pay more attention to forest management, which may reduce the incidence of forest disasters. In addition, since the initial starting point of this policy is poverty alleviation, and it is mainly implemented in economically deprived areas, the number of candidates in poor areas will be greater, that is, the impact of poor areas may be greater. Based on this, in the analysis of heterogeneity, we mainly analyzed the difference in the effect between large forestry provinces and small forestry provinces, as well as the eastern, central, and western regions (from high to low levels of social and economic development). We divided the 75th quantile of the per capita forest area in 2019 (0.39 hm2/person, with a median value of 0.21 hm2/person) into large forestry provinces (per capita forest area > 0.39 hm2) and small forestry provinces (0 < per capita forest area ≤ 0.39 hm2) to explore regional forest resource inventory differences.

Finally, we lack the comprehensive statistics at the current stage to analyze the reasons for this. Therefore, for the analysis of the reasons, we mainly combine our practical investigation of the implementation of the policy in Sichuan, the design of the policy-related system and the conclusions of other researchers, and make inferences about the causes through the methods of induction and summary. It should be noted that since the authors of this study are all from the Sichuan Province (Sichuan Province is not only a large forestry province but also located in western China), they are relatively familiar with the implementation of the Sichuan EFR policy. Therefore, empirical observations mainly come from Sichuan Province.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Table 2 reports the statistical results of the main variables. The results showed that the average annual number of forest fires in the province was 98.4, and the main forest fire grades included general fires and relatively serious fires. The average annual pest damage area in each province was 392,000 hectares, and the main pest type involved insect pests. In addition, the average annual forest coverage rate in each province was 32.7%, and the forestland financial expenditure was USD 52.63/0.07 km2. The statistics of the other main variables are shown below in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics.

Table 3 reports the economic and social differences between the experimental group and the control group. The results show that annual per-capita disposable income of farmers, population density, urbanization rate, forestry financial investment per unit area, information level, human capital level, precipitation and temperature were significantly higher for the control group than for the experimental group.

Table 3.

Differences in economic and social development between the experimental group and control group.

Table 4 reports the differences in forest resource protection between the experimental group and the control group. The results show that the incidence of forest fires and the area of harmful organisms were significantly higher in the experimental group than in the control group, while major fires and environmental emergencies were significantly lower in the experimental group than in the control group. In addition, the importance of forestry and forest coverage in the experimental group was lower than that in the control group, but this difference did not pass the mean significance test. The results described above indicate that the EFR policy may effectively reduce the probability of forest fires and harmful organisms.

Table 4.

Differences in the protection of forest resources between the experimental group and control group.

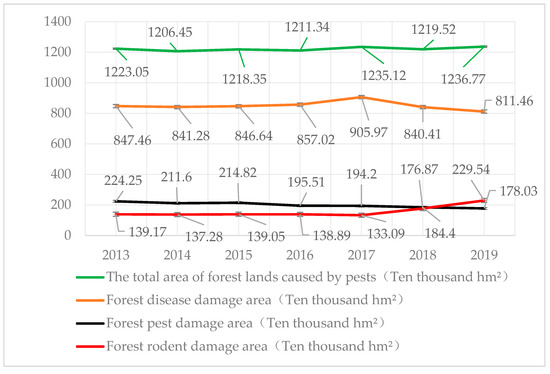

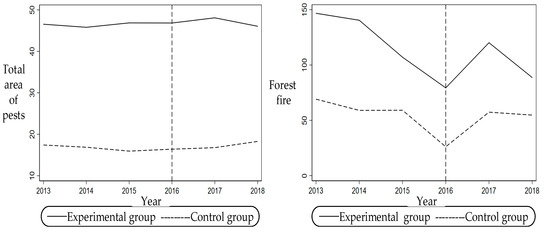

Table 5 reports the changes observed in the forest resource protection metrics of the experimental group before and after policy implementation. The results show that the incidence of relatively serious fires, environmental emergencies and pest-injured areas decreased after the policy was implemented, but these differences did not pass the mean significance test, and the total number of forest fires increased after the policy was implemented. The above results show that the policy’s effect on forest resource protection is not clear. Figure 5 shows the annual trends obtained for two main aspects in the experimental group and control group: forest fires and harmful organisms. The results show that after the implementation of the policy, the incidence of forest disasters did not decrease, and a certain time lag effect exists.

Table 5.

Changes in forest disasters between the experimental group and control group before and after policy implementation.

Figure 5.

Trends of pest damage and forest fires in policy implementation provinces and non-policy implementation provinces.

5.2. Analysis of Empirical Results

5.2.1. Basic Regression Results

Table 6 reports the regression results obtained for the EFR policy impacts on forest fires. From the estimation results of the regression model, the goodness of fit, R2, was 0.293 (at a significance level of 0.000), and this finding is guaranteed by gradually adding robust variables to the results (no other control variables are added in columns (1) and (2) of Table 6 and Table 7, while other control variables are added in columns (3) and (4)). This result shows that the variables included in the model contribute to the incidence of forest fires with an explanatory power of 29.3%.

Table 6.

Fixed-effects regression model results: logarithm of total forest fires.

Table 7.

Fixed-effects regression model: heavily damaging forest fires and above.

According to the results listed in Table 6 (3), the policy did not significantly reduce the incidence of forest fires. Even if the analysis window was changed to a two-year window, the policy still failed to significantly reduce the incidence of forest fires. In addition, Table 7 reports the impacts of the EFR policy on fires at the relatively serious grade and above, and the results still show that the policy did not significantly reduce the incidence of these fires.

Regarding the influence of other variables, the empirical results listed in Table 6 (3) show that disposable income, the urbanization rate, and the annual per-capita disposable income of farmers can significantly reduce the incidence of forest fires; that is, the higher the disposable income of the farmers is, the higher the urbanization rate is, and the more precipitation falls, the lower the incidence of forest fires in the region is. In contrast, the population density has a significant positive impact on the incidence of forest fires; that is, provinces with greater population densities have a higher incidences of forest fires.

Table 7 reports the impacts of the EFR policy on the number of fires graded relatively serious and above. The results showed that the policy failed to reduce relatively serious and more serious fires. The greater the importance of forestry, the greater the investment in financial forestland guarantee funds is, and this can effectively reduce the incidence of large fires.

Table 8 and Table 9 report the regression results of the total area of forest pests and the classification of pests. The findings reveal that the EFR policy can reduce the area infested by pests, but the results are not significant. Therefore, the implementation of the policy did not significantly reduce the area infested by forest pests.

Table 8.

Fixed-effects regression model results: logarithm of the area infested by forest pests.

Table 9.

Fixed-effects regression model results: classification of forest pests.

5.2.2. Analysis of Heterogeneous Effect

To further understand whether forest resource stocks and regional differences exist in the effect of the EFR policy implementation, this paper divided the 75th quantile of the per-capita forest area in 2019 (0.39 hm2/person, with a median value of 0.21 hm2/person) into large forestry provinces (per-capita forest area > 0.39 hm2) and small forestry provinces (0 < per-capita forest area ≤ 0.39 hm2) to explore regional forest resource inventory differences. In addition, regional differences were explored according to the division of China’s eastern, central and western economic regions.

Table 10 and Table 11 report the policy impacts on the incidence of forest disasters in forest resource stocks and the differential impacts among different regions, respectively. In terms of the analysis of the heterogeneity of the resource stocks, the policy significantly impacted the occurrence of large forest fires in major forestry provinces, but this impact was positive. After the implementation of the EFR policy, the policy had a larger and higher impact level. The incidence of forest fires increased, but other aspects did not reflect any significant impact.

Table 10.

Fixed effects regression model results: large forestry provinces vs. small forestry provinces.

Table 11.

Fixed effects regression model results: regional differences.

After analyzing the regional heterogeneity of the EFR policy, the results show that the EFR policy significantly impacted the total incidence of forest fires in the western region, but this impact was still positive. The above results show that, overall, the forest ranger policy reveals no significant differences in its corresponding forest disaster mitigation effects in terms of differences in forest resource inventories or economic geographic locations.

6. Discussion

Based on panel data from 31 provinces in China from 2014 to 2019, this study focuses on assessing the impact of EFR policy on forest disasters. Regardless of the overall level or the classification of disaster types, the results show that the implementation of the EFR policy did not reduce the incidence of forest disasters. This result is completely contrary to the conclusion of previous studies that the EFR policy can effectively reduce the incidence of forest disasters [23,24,25]. Furthermore, it also confirms previous researchers’ conjecture that the policy may have no effect on forest disaster management and control [12,26]. Through the comparison of argumentation methods, it is found that the previous conclusion, that the policy is effective for forest disaster prevention, is only based on the statistical data of individual provinces in a single year, without controlling the influence of other factors. Therefore, the conclusions of this study may be more reliable. However, why has this policy had no significant effect on forest disaster prevention and control? By combining the results of our practical investigation in Sichuan Province, the design of the policy system, the implementation process of the local government and the analysis of previous researchers, we infer and demonstrate three aspects: the selection behavior of forest rangers, the use behavior of labor funds, and the performance evaluation of patrols. The specific reasons may include:

First, when re-employing ecological rangers among impoverished people, officials are more inclined to select individuals from the most impoverished populations. According to ecological management requirements and protection goals, to effectively realize the effective management and protection of forestlands, it is necessary to require candidate selection methods that favor groups with higher human capital among impoverished populations to meet forest patrolling and protection requirements. However, Yan et al. (2020) [12] used data characterizing 33,681 EFRs in Sichuan Province to assess whether the EFRs are more likely to be re-employed and found that EFRs with lower income levels, whose poverty was not alleviated, and EFRs with lower human capital levels were more likely to be re-employed due to their access to renewal opportunities. In addition, some researchers pointed out that, in actual work, widespread problems exist associated with the selection and hiring of individuals from impoverished households that are not well qualified for ecological management and protection positions [32]. Based on these results, it can be speculated that, when implementing EFR policies, governmental departments are more inclined to reach the “poverty reduction” goal, rather than the dual goal of “poverty reduction and ecological management”.

Second, the labor funds of ecological rangers are broken down. According to the requirements of the “Administrative Measures for Ecological Forest Rangers of the impoverished population with Filing and Registration”, the central government shall provide guarantees in accordance with the labor subsidy standard of USD 1563.45/person/year, the main part of which must be used for forest rangers labor subsidies; this publication also indicated that localities can reflect on the local actual situation to consider the EFR management and protection subsidy standards, management and protection areas, difficulty of management and protection duties and original EFR labor subsidy level, as well as other factors to determine the specific subsidy standard. In the early stage of the EFR policy implementation, the labor wages of impoverished EFRs in various regions of Sichuan Province were essentially implemented at the standard of USD 1563.2328/person/year, but according to the policy goals, by the end of 2020, all poverty-stricken people had to be relieved of poverty. Thus, constraints in various regions began to dilute labor subsidy funds for forest guards, and employment targets were increased to achieve greater poverty reduction targets. Through the data of 33,681 forest rangers who worked in Sichuan Province from 2016 to 2019, it is known that the average annual labor subsidy was USD 791.1521, and the minimum subsidy was USD 218.8526. Clearly, the dilution of labor subsidy funds greatly reduces the enthusiasm of EFRs when managing and protecting forests, and this policy has gradually evolved into a direct income subsidy policy. It can also be inferred that the current orientation of the policy is mainly aimed at the “poverty reduction” goal.

Third, performance appraisals of forest rangers are mostly mere formalities and lack standardization and restriction. Through field inspections of typical cases in the three major forestry counties of Pingwu County, Qingchuan County, and Wenchuan County in Sichuan Province, we found that EFR assessments are mainly performed by village committees and that the main assessment content involves an inspection of the EFRs’ mountain logs; however, these logs mostly contain the behavior of the individual writing the log, and the corresponding assessment is singular and lacks reference value. Additionally, the assessments of the village committees are often not strict due to factors such as human sentiment and assessment costs. Regarding the assessments of local governments, higher-level governments also give more attention to the selection and funding of the policy implementation assessments of lower-level governments than to assessing the EFRs themselves. The lack of constraints on environmental protection indicators has also led to deficiencies in the assessment and implementation of local governments, as reflected in some previous studies. After analyzing the EFR policy, personnel have pointed out that the policy neglected forestry management departments when considering the management of forest rangers [33]. In addition, the salary structure of EFRs is singular and fixed, and there are no performance-based salary incentives. Therefore, on the basis of the lack of any incentive, forest rangers have a weak sense of competition and lack subjective initiative. Therefore, in the absence of effective supervision and incentives, it is difficult for impoverished EFRs to have the initiative to conduct serious inspections. This also shows that the goal orientation of the EFR policy has focused more on “poverty reduction” than on “ecological protection”.

In summary, from the perspective of the systematic design and implementation of EFR policies at three levels, the selection of renewal targets for EFRs, the use of labor subsidy funds, and the evaluation of management and protection performances, the implementation process of the EFR policy was found to be seriously tilted towards the goal of “poverty reduction”. Institutional considerations for the realization of the “ecological protection” goal were ignored. Based on these results, we can infer that it is precisely because of the choice of the policy’s goal orientation that the policy lacks specific institutional considerations for the realization of the “environmental protection” goal in the processes of the systemic policy design and practices. It is precisely because of the lack of assessment requirements or constraints for forest disaster prevention and control, that local governments and ecological forest rangers do not care about whether forest disasters occur or not, which increased the opportunism of local governments and ecological rangers in ecological management and protection behavior. In the end, this policy did not effectively reduce the incidence of forest disasters.

From the perspective of the integrity of the data and evaluation methods used herein, the data and policy evaluation methods used in this study were more representative and convincing than those used in previous studies. However, the analysis described in this paper still has the following deficiencies due to limitations associated with data uncertainties: (1) the EFR policy was mainly implemented for impoverished populations in collective forests, but the forest disaster data failed to effectively differentiate between collective forests and state-owned forests, making it difficult to assess the impacts of the EFR policy on collective forest disasters and better clarify the ecological effects of the policy; (2) this article considers only the provincial level, though the experimental group and control group differ greatly in their forestry and socio-economic development endowments, thus reducing their comparability. It would be more effective to conduct analyses at the county scale or smaller village scale to evaluate the impact of the EFR policy on forest disasters; (3) in the cause inference section, this study considered only the implementation of experienced observations, documents and EFR policy system design in Sichuan Province to infer that the policy did not effectively reduce forest disasters. Some deviations in the conclusions obtained regarding the reasons for the disaster incidence rate may have arisen if different provinces were included. Based on the deficiencies of this article, in the future, we will further evaluate the impact of this policy on forest disasters and other effects from the perspective of counties and villages. At the same time, through the implementation of this policy, we will also conduct a more comprehensive investigation of the opportunism of local governments and ecological rangers in the implementation of this policy. This is expected to provide a decision-making reference for the improvement of this policy.

7. Conclusions and Policy Implications

7.1. Conclusions

In the context of China’s eco-compensation policy and considering the dual “poverty reduction and environmental protection” goals of the policy, this paper organized China’s provincial-level forest disaster data collected from 2014 to 2019, combined these data with the natural experiment of the policy as an external shock, and used the DID method to evaluate the impact of the EFR policy on forest disasters. The main conclusions of this article are as follows:

- (1)

- The empirical results at the provincial level show that the implementation of China’s EFR policy did not effectively reduce the incidence of forest disasters. In short, the implementation of the EFR policy did not effectively reduce the incidence of forest fires, forest pests, forest diseases, and forest rodents. Moreover, this effect has no significant differences in the stock of forest resources, the level of forest disasters, or regional differences. Therefore, proposition 1 proposed in this paper is supported.

- (2)

- The EFR policy failed to effectively reduce the incidence of forest disasters. The main reason for this is that the policy is currently being implemented. Due to the pressure of the “poverty reduction” assessment, the local government mainly chose the policy’s “poverty reduction goals”, and the central government did not include the indicators of “effective forest disaster prevention and control” in the performance evaluation of local governments during the evaluation process, which in turn led the local governments to disregard the performance evaluation of ecological forest rangers’ ecological protection effect. In this way, the opportunism of local governments and ecological rangers was strengthened, and attention to forest disasters was neglected. In the end, the policy did not achieve the goal of reducing the incidence of forest disasters.

- (3)

- Increasing the urbanization rate (reducing the rural population), increasing the income level of residents, and abundant precipitation can effectively reduce the incidence of forest fires. Therefore, this result also shows that, by adjusting the frequency of population activities, increasing residents’ income, and then improving the level of awareness, it is beneficial for reducing the incidence of forest disasters.

7.2. Policy Implications

The analysis and conclusions in this study have certain enlightening significance for policy making. The novel information relevant to the government is as follows: the “ecological protection” goal of the EFR policy should be strengthened. Under the background of essentially completing urgent poverty reduction tasks in the past and alleviating the pressure of local poverty alleviation, the orientation of the EFR policy objectives should shift from the “poverty reduction” goal focused on the past to the dual goal of “poverty reduction and ecological protection”; next, regarding “ecological management and protection”, the appraisal index corresponding to the target is included in the content of the performance appraisal. Human intervention can accelerate the restoration of forests following disasters [34,35]. Therefore, on the one hand, it is necessary to quantify the local government’s “forest disaster” incidence indicators during the EFR policy implementation. Punishment and reward mechanisms should be incorporated into EFR assessments, and the selection and employment conditions and salary system should be gradually adjusted to adapt to the new situation under which China’s ecological civilization construction and poverty alleviation are effectively integrated with rural revitalization. In short, the design and optimization of ecological compensation policies, such as impoverished EFRs, should promote the matching of policy objectives and management systems to effectively obtain the policy goals and improve the policy implementation efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y., X.D., Y.Q., C.L., Q.H. and F.W.; Formal analysis, Z.Y., X.D. and C.L.; Funding acquisition, Y.Q. and F.W.; Methodology, Z.Y. and F.W.; Visualization, Z.Y.; Writing—original draft, Z.Y. and Y.Q.; Writing—review and editing, Z.Y., Y.Q., F.W., Q.H. and X.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 14XGL003, The National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 20BSH107, which funded this study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

All authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 14XGL003 and 20BSH107).

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Notes and information reference source.

Table A1.

Notes and information reference source.

| Numbering | Notes and Reference Source |

|---|---|

| 1.1 | https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_3263397, accessed on 21 March 2021 |

| 1.2 | http://www.forestry.gov.cn/main/5383/20190930/100821670658921.html, accessed on 22 March 2021 |

| 1.3 | The financial support standard for the ecological forest rangers is USD 1563.45/person/year, and is mainly used for the labor compensation of forest rangers. This standard is much higher than the poverty alleviation standard of USD 359.62/person-year (the constant price in 2011) |

| 1.4 | http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2011/content_2020905.htm, accessed on 22 March 2021 |

| 1.5 | http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2015/1208/c1001-27898134.html, accessed on 22 March 2021 |

| 1.6 | http://www.greentimes.com/greentimepaper/html/2016-08/30/content_3294090.htm, accessed on 15 February 2021 |

| 1.7 | https://www.66law.cn/tiaoli/23.aspx, accessed on 15 February 2021 |

| 1.8 | http://aqxxgk.anqing.gov.cn/show.php?id=658441, accessed on 15 February 2021 |

| 1.9 | https://www.docin.com/p-2162409316.html, accessed on 15 February 2021 |

| 1.10 | http://www.stats.gov.cn/, accessed on 24 January 2021 |

Appendix B

According to the “Notice on Adjusting Fire Levels” issued by the Ministry of Public Security:

General fires; relatively serious fires; especially serious fires; particularly big serious fires

- (1)

- General fire. A fire that caused the death of less than 3 people, or severely injured less than 10 people, or caused direct property damage of less than 10 million yuan.

- (2)

- Relatively serious fires. A fire that caused the death of more than 3 people and less than 10 people, or serious injuries of more than 10 people and less than 50 people, or direct property losses of more than 10 million yuan and less than 50 million yuan.

- (3)

- Especially serious fires. A fire that caused more than 10 deaths but less than 30 people, or serious injuries of more than 50 people but less than 100 people, or direct property losses of more than 50 million yuan and less than 100 million yuan.

- (4)

- Particularly big serious fire. A fire that caused more than 30 deaths, or serious injuries of more than 100 people, or direct property losses of more than 100 million yuan.

At: https://kuai.so.com/7ff516d2d5f8d497bd9b151689be28fa/wenda/selectedabstracts/www.yebaike.com?src=wenda_abstract, accessed on 15 February 2021.

References

- Wu, Y.Z.; Zhang, Z.G. The DEA-Tobit Model Analysis of Forestry Ecological Safety Efficiency and Its Influencing Factors—Based on the Symbiosis between Ecology and Industry. Resour. Environ. Yangtze River Basin 2021, 30, 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Study on the impact of forest fire risk on the development of forestry econom. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2014, 30, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Kiel, K.A.; Matheson, V.A. The effect of natural disasters on housing prices: An examination of the Fourmile Canyon fire. J. For. Econ. 2018, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di, L.Y.; Sun, R.Y. Summary of China’s Forest Fire Research. J. Catastr. 2007, 4, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, F.; Chen, H.S. Classification and Cause Analysis of Forest Disasters and Forestry Accidents. Guangdong For. Sci. Technol. 2007, 23, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.T.; Jiang, Y. The evolution of the spatiotemporal pattern of forest ecological security in China and the diagnosis of obstacles. Stat. Decis. 2019, 35, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.Z. Property Reform and Resource Management: An Analysis Based on Forest Disaster. China Rural Econ. 2015, 10, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J.H.; Feng, Y.Y. Spatial Scanning of Deep Poverty in Rural China and Geographical Exploration of Poverty Differentiation Mechanism. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2020, 75, 769–788. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Zhu, K.N.; Jin, L.S. International experience and reference for poverty alleviation by paying for environmental services. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2019, 33, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, S.; Pagiola, S.; Wunder, S. Payments for environmental services in Costa Rica. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 65, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownson, K.; Elizabeth, P.A.; Ferreira, S.; Wenger, S.; Fowler, L.; German, L. Governance of Payments for Ecosystem Ecosystem services influences social and environmental outcomes in Costa Rica. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 174, 106659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.C.; Wei, F.; Chen, Y.R.; Deng, X.; Qi, Y.B. The Policy of Ecological Forest Rangers (EFRs) for the Poor: Goal Positioning and Realistic Choices—Evidence from the Re-Employment Behavior of EFRs in Sichuan, China. Land 2020, 9, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Amado, L.R.; Pérez, M.R.; Escutia, F.R.; García, S.B.; Mejía, E.C. Efficiency of Payments for Environmental Services: Equity and additionality in a case study from a Biosphere Reserve in Chiapas, Mexico. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 2361–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaissière, A.; Calvet, F.Q.; Levrel, H.; Wunder, S. Biodiversity offsets and payments for environmental services: Clarifying the family ties. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 169, 106428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pates, N.J.; Hendricks, N.P. Additionality from Payments for Environmental Services with Technology Diffusion. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 102, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapeyre, R.; Froger, G.; Hrabanski, M. Biodiversity offsets as market-based instruments for ecosystem services? From discourses to practice. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 15, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.C.; Loft, L.; Pham, T.T. How fair can incentive-based conservation get? The interdependence of distributional and contextual equity in Vietnam’s payments for Forest Environmental Services Program. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 160, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Corbera, E.; Lapeyre, R. Payments for Environmental Services and Motivation Crowding: Towards a Conceptual Framework. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 156, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T. Reflections on the Poverty Alleviation Policy of Actively Expanding Public Welfare Posts. China Natl. Cond. Natl. Power 2017, 11, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.Y.; Wu, J. Analysis of the Impact of Ecological Compensation Projects on Poverty Alleviation—Based on the Perspective of Farmers’ Heterogeneity. Beijing Soc. Sci. 2016, 1, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.F.; Yin, H.D.; Zhang, Z.T.; Ke, S.F. Is ecological compensation conducive to precision poverty alleviation?—Taking the construction area of the Three Gorges Ecological Barrier as an example. J. Northwest Sci.-Tech. Univ. Agric. For. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 18, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Kong, D.S.; Jin, L.H. Ecological compensation beneficial to poverty reduction? An empirical analysis of three counties in Guizhou province based on the propensity score matching method. Rural Econ. 2017, 9, 48–55. Available online: http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-NCJJ201709010.htm (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Liu, P.; Liu, P.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of the effect of the ecological forest ranger policy for the population in Guizhou Province. Green Financ. Account. 2017, 1, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Teng, S.H.A. Win-win situation for ecological poverty alleviation and resource management and protection—A record of the work of ecological forest rangers in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Inn. Mong. For. 2018, 12, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, M.X. Implementation and practice of poverty alleviation policies for ecological forest rangers in Qinghai. Economist 2020, 9, 135–137. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.J.; Li, D. The status quo and suggestions for the management of ecological forest rangers’ public welfare posts in Li County, Aba Prefecture. Green Technol. 2019, 3, 138–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.G.; Wang, J. Adjustable Connection: An Explanation of the Evolution of local Government Policy Executive Power. J. Public Manag. 2021, 18, 140–152+175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.A. Research on the Promotion Championship Mode of Local Officials in China. Econ. Res. 2007, 7, 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.Z.; Sun, P.B.; Xuan, Y. Does the local government’s environmental objective constraints affect industrial transformation and upgrading? Econ. Res. 2020, 55, 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R.D.; Lin, M.Y. The research trends of the double difference method and its application in public policy evaluation. Financ. Financ. Think Tank 2018, 3, 84–111+143–144. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, T.; Zhou, H.X.; Deng, J. China’s forest fire risk zoning based on cluster analysis. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2015, 31, 1458–1461+1533+1553. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, M.Y. China Ecological Public Welfare Post Policy and Practice: Progress, Problems and Suggestions. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 44, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Problems and countermeasures of ecological forest guards for the impoverished population on file establishment. Green Sci. Technol. 2019, 21, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, M.X. Proposals for Ecological Poverty Alleviation: The Central Government’s implementation of the ecological poverty alleviation policy for the impoverished population in Qinghai. Economist 2019, 11, 145–146. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, W.T.; Ma, Y.; Chen, M.; Xiao, Z.S.; Shu, Z.F.; Chen, L.J.; Xiao, W.H.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhang, S.Y. Analysis of Ice Storm Impact on and Post-Disaster Recovery of Typical Subtropical Forests in Southeast China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).