Polycentric Environmental Governance to Achieving SDG 16: Evidence from Southeast Asia and Eastern Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Polycentric Governance in Natural Resources Management

2.2. Environmental Governance in SDG 16

| SDG 16 Target | Elder and Olsen [43] | UNEP [6] |

|---|---|---|

| 16.3 Rule of Law and Justice for All | v | v |

| 16.6 Effective, accountable, and transparent institution at all levels | v | v |

| 16.7 Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making at all levels | v | v |

| 16.8 Broaden and strengthen the participation of developing countries in the institutions of global governance | - | v |

| 16.10 Ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms following national legislation and international agreements | v | v |

| 16.B Promote and enforce non-discriminatory laws and policies for sustainable development | - | v |

2.3. Gaps in the Literature

2.4. Conceptual Framework

3. Methodology and Case Studies

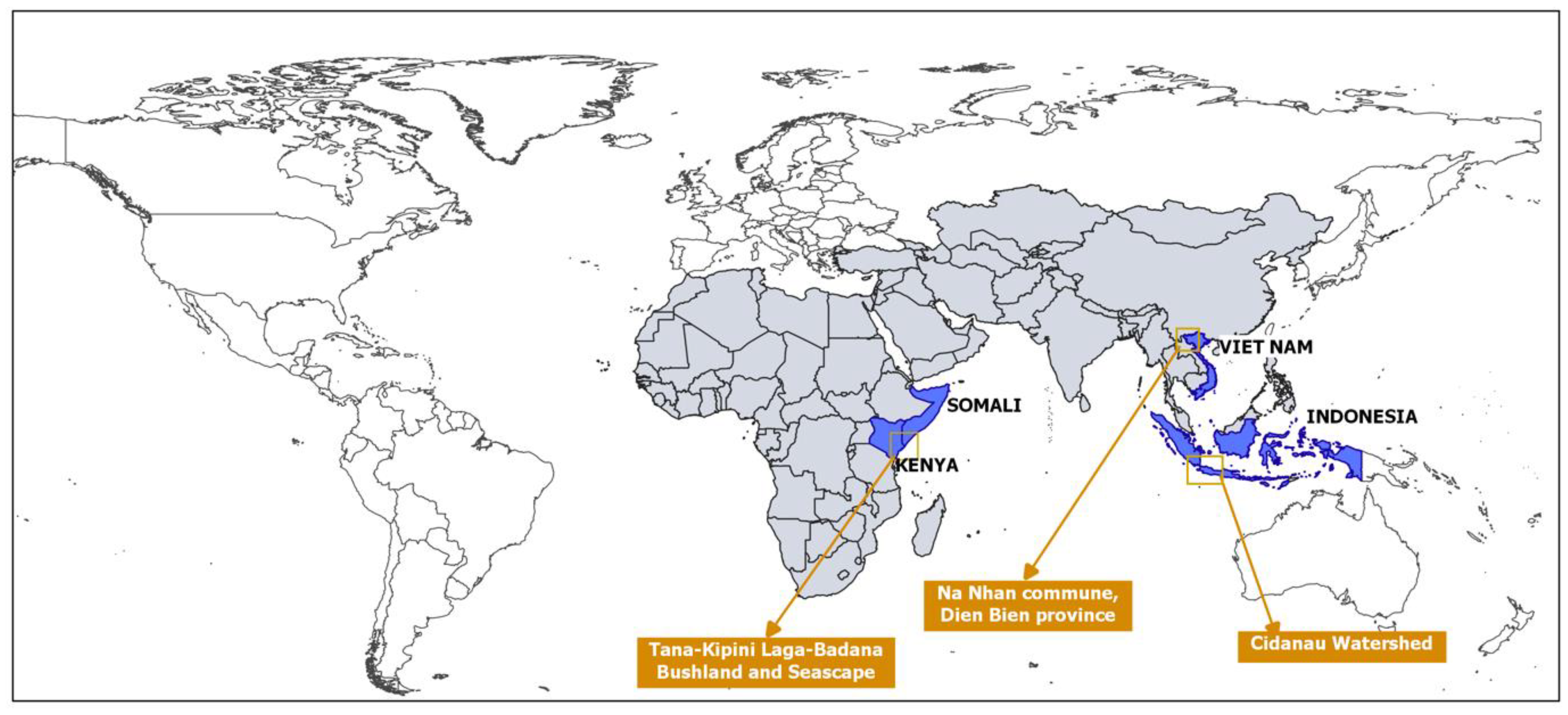

3.1. Cidanau Watershed, Indonesia

3.2. Na Nhan Commune, Dien Bien Province, Northwest Vietnam

3.3. Tana-Kipini-Laga Badana Bush Land and Seascape, Kenya–Somalia

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. SDG 16.3: Promote Rule of Law and Ensure Justice for All

4.2. SDG 16.6: Effective, Accountable, and Transparent Institutions at All Levels

4.3. SDG 16.7:Ensure Responsive, Inclusive, Participatory and Representative Decision-Making at All Levels

5. Conclusions and Recommendation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Washington, H. Demystifying Sustainability: Towards Real Solutions; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmidi, T.; Hook Law, S.; Jafari, Y. Resource Curse: New Evidence on the Role of Institutions. Int. Econ. J. 2014, 28, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, D. What the Absence of the Environment in Sdg 16 on Peace and Security Should Tell Us; CEOBS: West Yorkshire, UK, 2016; Available online: https://ceobs.org/what-the-absence-of-the-environment-in-sdg16-on-peace-and-security-should-tell-us/ (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Mehlum, H.; Moene, K.; Torvik, R. Institutions and the resource curse. Econ. J. 2006, 116, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hope Sr, K.R. Peace, justice and inclusive institutions: Overcoming challenges to the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 16. Glob. Change Peace Secur. 2020, 32, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. SDG 16. In Issue Brief; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dohlman, E. Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development in the Post-2015 Framework. In Proceedings of the UN Expert Group Meeting, New York, NY, USA, 4–5 December 2014; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/egm/pdf/presentation_session_iii_dohlman.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Menton, M.; Larrea, C.; Latorre, S.; Martinez-Alier, J.; Peck, M.; Temper, L.; Walter, M. Environmental justice and the SDGs: From synergies to gaps and contradictions. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WRI. Sustainable Development Goal 16. Available online: https://www.wri.org/sdg-16 (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- McDermott, C.L.; Acheampong, E.; Arora-Jonsson, S.; Asare, R.; de Jong, W.; Hirons, M.; Khatun, K.; Menton, M.; Nunan, F.; Poudyal, M.; et al. SDG 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions–a political ecology perspective. In Sustainable Development Goals: Their Impacts on Forests and People; Katila, P., Colfer, C.J.P., de Jong, W., Galloway, G., Pacheco, P., Winkel, G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 510–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.H. Advantages of a polycentric approach to climate change policy. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Görg, C. Landscape governance: The “politics of scale” and the “natural” conditions of places. Geoforum 2007, 38, 954–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitema, D.; Mostert, E.; Egas, W.; Moellenkamp, S.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Yalcin, R. Adaptive water governance: Assessing the institutional prescriptions of adaptive (co-) management from a governance perspective and defining a research agenda. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goegele, H. Towards a polycentric approach to implement the 2030 Agenda. In Proceedings of the Workshop on the Ostrom Workshop 6, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA, 19–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molle, F.; Mamanpoush, A. Scale, governance and the management of river basins: A case study from Central Iran. Geoforum 2012, 43, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termeer, C.J.A.M.; Dewulf, A.; van Lieshout, M. Disentangling scale approaches in governance research: Comparing monocentric, multilevel, and adaptive governance. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Coping with tragedies of the commons. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 1999, 2, 493–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K.P.; Ostrom, E. Analyzing decentralized resource regimes from a polycentric perspective. Policy Sci. 2008, 41, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendra, H.; Ostrom, E. Polycentric governance of multifunctional forested landscapes. Int. J. Commons 2012, 6, 104–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, E.; McCord, P.; Dell’Angelo, J.; Evans, T. Collective action in a polycentric water governance system. Environ. Policy Gov. 2018, 28, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, T.; Bock, B.; Kirk, M. Polycentrism and poverty: Experiences of rural water supply reform in Namibia. Water Altern. 2009, 2, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Lankford, B.; Hepworth, N. The cathedral and the bazaar: Monocentric and polycentric river basin management. Water Altern. 2010, 3, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Rist, S.; Chidambaranathan, M.; Escobar, C.; Wiesmann, U.; Zimmermann, A. Moving from sustainable management to sustainable governance of natural resources: The role of social learning processes in rural India, Bolivia and Mali. J. Rural Stud. 2007, 23, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, K.; Gruby, R.L. Polycentric systems of governance: A theoretical model for the commons. Policy Stud. J. 2019, 47, 927–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruns, B. Challenges of Polycentric Water Governance in Southeast Asia: Awkward Facts, Missing Mechanisms, and Working with Institutional Diversity. In Redefining Diversity & Dynamics of Natural Resources Management in Asia; Chapter 4; Ganesh, P.S., Ujjwal, P., Helmi, Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimona, B.; van Noordwijk, M.; de Groot, R.; Leemans, R. Fairly efficient, efficiently fair: Lessons from designing and testing payment schemes for ecosystem services in Asia. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abers, R.N. Organizing for Governance: Building Collaboration in Brazilian River Basins. World Dev. 2007, 35, 1450–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelcich, S. Towards polycentric governance of small-scale fisheries: Insights from the new ‘Management Plans’ policy in Chile. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2014, 24, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, E.; Washington-Ottombre, C.; Dell’Angelo, J.; Cole, D.; Evans, T. Polycentric Governance and Irrigation Reform in Kenya. Governance 2016, 29, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalika, M.C.S.; Meire, P.; Ngaga, Y.M. Exploring watershed conservation and water governance along Pangani River Basin, Tanzania. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCord, P.; Dell’Angelo, J.; Baldwin, E.; Evans, T. Polycentric Transformation in Kenyan Water Governance: A Dynamic Analysis of Institutional and Social-Ecological Change. Policy Stud. J. 2017, 45, 633–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushley, B.R. REDD+ policy making in Nepal: Toward state-centric, polycentric, or market-oriented governance? Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Long, H.; Liu, J.; Tu, C.; Fu, Y. From State-controlled to Polycentric Governance in Forest Landscape Restoration: The Case of the Ecological Forest Purchase Program in Yong’an Municipality of China. Environ. Manag. 2018, 62, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, R.; Langston, J.; Margules, C.; Boedhihartono, A.; Lim, H.; Sari, D.; Sururi, Y.; Sayer, J. Governance Challenges in an Eastern Indonesian Forest Landscape. Sustainability 2018, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caron, C.; Fenner, S. Forest Access and Polycentric Governance in Zambia’s Eastern Province: Insights for REDD. Int. For. Rev. 2017, 19, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pedersen, R.H. Access to land reconsidered: The land grab, polycentric governance and Tanzania’s new wave land reform. Geoforum 2016, 72, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros-Tonen, M.; Derkyi, M.; Insaidoo, T. From co-management to landscape governance: Whither Ghana’s modified taungya system? Forests 2014, 5, 2996–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falk, T.; Spangenberg, J.H.; Siegmund-Schultze, M.; Kobbe, S.; Feike, T.; Kuebler, D.; Settele, J.; Vorlaufer, T. Identifying governance challenges in ecosystem services management–Conceptual considerations and comparison of global forest cases. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 32, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, J.P.; Fidelman, P.; Sattler, C.; Schröter, B.; Maron, M.; Eigenbrod, F.; Fortin, M.-J.; Hohlenwerger, C.; Rhodes, J.R. Connecting governance interventions to ecosystem services provision: A social-ecological network approach. People Nat. 2021, 3, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovic, A.; Cooper, H.; Nguyen, A.M. Institutionalisation of SDG 16: More a trickle than a cascade? Soc. Altern. 2018, 37, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Whaites, A. Achieving the Impossible: Can We Be SDG 16 Believers? GovNet Background Paper. 2016, 2, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, M.; Olsen, S.H. The Design of Environmental Priorities in the SDG s. Glob. Policy 2019, 10, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amaruzaman, S.; Bardsley, K.D.; Stringer, R. Reflexive Policies and the Complex Socio-ecological Systems of the Upland Landscapes in Indonesia. Agric. Hum. Values 2022. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Monitoring the Implementation of SDG 16 for Peaceful, Just and Inclusive Societies: Pilot Initiative on National-Level Monitoring of SDG 16; UNDP: Oslo, Norway, 2017; 37p, Available online: file:///C:/Users/MDPI/AppData/Local/Temp/Monitoring%20to%20Implement%20SDG16_Pilot%20Initiative.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- UNEP. GOAL 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions. Available online: https://www.unenvironment.org/explore-topics/sustainable-development-goals/why-do-sustainable-development-goals-matter/goal-16 (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Meuleman, L.; Niestroy, I. Common but differentiated governance: A metagovernance approach to make the SDGs work. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12295–12321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lemos, M.C.; Agrawal, A. Environmental Governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2006, 31, 297–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, K.J.; Garcia Rodrigues, J.; Albrecht, E.; Crockett, E.T.H. Governance of ecosystem services: A review of empirical literature. Ecosyst. People 2021, 17, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö. Collaborative environmental governance: Achieving collective action in social-ecological systems. Science 2017, 357, eaan1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frantzeskaki, N. Seven lessons for planning nature-based solutions in cities. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 93, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, M. Governance in transboundary conservation: How institutional structure and path dependence matter. Conserv. Soc. 2013, 11, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Pernetta, J.C.; Duda, A.M. Towards a new paradigm for transboundary water governance: Implementing regional frameworks through local actions. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2013, 85, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandl, M. Towards the monitoring of Goal 16 of the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs). In UN Sabbatical Leave Research Report; UN: Helshinki, Finland, 2017; 100p, Available online: https://hr.un.org/sites/hr.un.org/files/editors/u604/Towards%20the%20monitoring%20of%20Goal%2016%20of%20ther%20SDG.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Knieper, C. The capacity of water governance to deal with the climate change adaptation challenge: Using fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis to distinguish between polycentric, fragmented and centralized regimes. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 29, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buytaert, W.; Dewulf, A.; Bièvre, B.D.; Clark, J.; Hannah, D.M. Citizen Science for Water Resources Management: Toward Polycentric Monitoring and Governance? J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2016, 142, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bixler, R.P. From Community Forest Management to Polycentric Governance: Assessing Evidence from the Bottom Up. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2014, 27, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaruzaman, S.; Rahadian, N.; Leimona, B. Role of intermediaries in the Payment for Environmental Services scheme: Lessons learnt in the Cidanau watershed, Indonesia. In Co-Investment in Ecosystem Services: Global Lessons from Payment and Incentive Schemes; World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF): Nairobi, Kenya, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Do, T.H.; Nguyen, V.T.; Vu, T.P. Landscape Tree Cover Transition, Drivers and Stakeholder Perspectives–A Case Study in Na Nhan commune, Dien Bien Province, Vietnam; World Agroforestry Centre: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017; 30p. [Google Scholar]

- Do, T.H.; Vu, T.P.; Catacutan, D. Governing Landscapes for Ecosystem Services: A Participatory Land-Use Scenario Development in the Northwest Montane Region of Vietnam. Environ. Manag. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanui; Catacutan, D.C. TKLBBs Cross-Border MSP-A Case Study; IFPRI: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tanui, J.; Koech, G.; Catacutan, D.C. Governing a Shared, Critical Biodiversity Landscape through Cross-Border Dialogue Platform; World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF): Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.T.; Bennett, K.; Vu, T.P.; Brunner, J.; Le Ngoc, D.; Nguyen, D.T. Payments for Forest Environmental Services in Vietnam: From Policy to Practice; CIFOR: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McElwee, P.; Huber, B.; Nguyễn, T.H.V. Hybrid outcomes of payments for ecosystem services policies in Vietnam: Between theory and practice. Dev. Change 2020, 51, 253–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neef, A. Transforming rural water governance: Towards deliberative and polycentric models? Water Altern. 2009, 2, 53. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, F.L.; Leimona, B.; Amaruzaman, S.; Rahadian, N.P.; Carrasco, L.R. Identifying payments for ecosystem services participants through social or spatial targeting? Exploring the outcomes of group level contracts. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2019, 1, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Satterthwaite, M.L.; Dhital, S. Measuring access to justice: Transformation and technicality in SDG 16.3. Glob. Policy 2019, 10, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Visseren-Hamakers, I.J. Integrative environmental governance: Enhancing governance in the era of synergies. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.H.; Vu, T.P.; Nguyen, V.T.; Catacutan, D. Payment for forest environmental services in Vietnam: An analysis of buyers’ perspectives and willingness. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 32, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libert-Amico, A.; Larson, A.M. Forestry Decentralization in the Context of Global Carbon Priorities: New Challenges for Subnational Governments. Front. For. Glob. Change 2020, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pham, T.T.; Moeliono, M.; Brockhaus, M.; Le, D.N.; Wong, G.Y.; Le, T.M. Local preferences and strategies for effective, efficient, and equitable distribution of PES revenues in Vietnam: Lessons for REDD+. Hum. Ecol. 2014, 42, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeliono, M.; Pham, T.T.; Le, N.D.; Brockhaus, M.; Wong, G.; Kallio, M.; Nguyen, D.T. Local governance, social networks and REDD+: Lessons from swidden communities in Vietnam. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 44, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderlin, W.D.; Sills, E.; Duchelle, A.E.; Ekaputri, A.; Kweka, D.; Toniolo, M.; Ball, S.; Doggart, N.; Pratama, C.; Padilla, J. REDD+ at a critical juncture: Assessing the limits of polycentric governance for achieving climate change mitigation. Int. For. Rev. 2015, 17, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikor, T. The allocation of forestry land in Vietnam: Did it cause the expansion of forests in the northwest? For. Policy Econ. 2001, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.K.P.; Van Der Zouwen, M.; Arts, B. Challenges of forest governance: The case of forest rehabilitation in Vietnam. Public Organ. Rev. 2019, 19, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, F.; Erbaugh, J.T.; Leimona, B.; Amaruzaman, S.; Rahadian, N.P.; Carrasco, L. Green without envy: How social capital alleviates tensions from a Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) program in Indonesia. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| SDG 16 Targets | Polycentric Governance Characteristics/Elements | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political Will | Legal Framework | Support from Higher-Level Government | Capacity Building for Local Actors | |

| 16.3 Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all | Required | Highly required | Highly required | Required |

| 16.6 Develop effective, accountable, and transparent institutions at all levels | Central Government shares authority and responsibility with the Local Government and other related institutions | Required | Highly required through legal, technical, financial means | Required depending on local needs |

| 16.7 Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making at all levels | Central and Local Government share roles in co-management and co-regulation of resources with other institutions. | Required, although not essential in some cases | Required through legal and technical support | Required, but also depends on local needs |

| 16.8 Broaden and strengthen the participation of developing countries in the institutions of global governance * | Required, at the global level | Required, at the global level | Required through legal and technical support at the global level | Required, depending on country needs |

| 16.10 Ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, following national legislation and international agreements * | Required | Required | Required | Required, but also depends on the local needs |

| 16.B Promote and enforce non-discriminatory laws and policies for sustainable development * | Required | Required | Required | Required, depends on the local needs |

| Study Site | Northwest Vietnam | Kenya-Somalia | Cidanau, Indonesia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape | Upland catchment of NamRon river | Bush Land and Seascape | CWatershed |

| Dominant land use | Forest + agriculture | Protected biodiversity corridor, forest, grazing land | Protected natural reserve area + Agriculture (agroforest) |

| Governance system | Centralised (represented by Commune People Committee, one level above the village) | Decentralised | Decentralised to district/city and the village level. The Provincial Government is the representative of the Central Government |

| Governance level | Na Nhan Commune of Dien Bien Province | Cross-border area (Northeast Kenya and South Somalia) | Cilegon City, Serang District and Pandeglang District of Banten Province |

| Area size (ha) | 7600 | 2,000,000 | 26,000 |

| Issues/challenges | Contested use of forest land, forest degradation, inequitable payment of forest ecosystem services | Resource use and human conflict, unclear tenure, biodiversity loss, land degradation, lack of livelihood opportunities | Upstream: Agroforest conversion; deforestation; poverty Downstream: Sedimentation; reduced water supply |

| Sustainable management goal/response | Payment for forest ecosystem services, land use planning | Land use planning, economic development planning, the establishment of protected area network | Integrated watershed management, Payment for ecosystem services |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amaruzaman, S.; Trong Hoan, D.; Catacutan, D.; Leimona, B.; Malesu, M. Polycentric Environmental Governance to Achieving SDG 16: Evidence from Southeast Asia and Eastern Africa. Forests 2022, 13, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13010068

Amaruzaman S, Trong Hoan D, Catacutan D, Leimona B, Malesu M. Polycentric Environmental Governance to Achieving SDG 16: Evidence from Southeast Asia and Eastern Africa. Forests. 2022; 13(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13010068

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmaruzaman, Sacha, Do Trong Hoan, Delia Catacutan, Beria Leimona, and Maimbo Malesu. 2022. "Polycentric Environmental Governance to Achieving SDG 16: Evidence from Southeast Asia and Eastern Africa" Forests 13, no. 1: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13010068

APA StyleAmaruzaman, S., Trong Hoan, D., Catacutan, D., Leimona, B., & Malesu, M. (2022). Polycentric Environmental Governance to Achieving SDG 16: Evidence from Southeast Asia and Eastern Africa. Forests, 13(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13010068