Abstract

Planted forests include forests established through human planting or deliberate seeding. They are systems that offer us timber and non-timber forest products and ecosystem services, such as wildlife protection, carbon sequestration, soil, and watershed maintenance. Brazil has 7.6 million hectares of planted forests, with 72% of the total area occupied by Eucalyptus spp. A favorable climate and management and genetic improvement research are the main factors responsible for high productivity. In recent years, the expansion of planted areas has been accompanied by the commercial release of several pesticides, mainly herbicides. A recent change in the Brazilian legislation allows mixing phytosanitary products in a spray tank, having a new approach to managing pests, diseases, and weeds. Antagonism is the main risk of tank mixes, and to reduce the dangers associated with this practice, we review all products registered for growing Eucalyptus. This literature review aims to identify the effects of product mixtures registered for Eucalyptus reported for other crops. In addition, environmental and social risk assessment has been widely adopted to export wood and cellulose, making the results of this review an indispensable tool in identifying the nature and degree of risks associated with pesticides. The results classify the effects of the mixtures as an additive, antagonistic or synergistic. The use of pesticide tank mixtures has the potential for expansion. However, there are still challenges regarding variations in the effects and applications in different climatic conditions. Therefore, studies that prove efficient mixtures for the forest sector are essential and the training of human resources.

1. Introduction

Global forests planted with Eucalyptus spp. (mostly Eucalyptus grandis W. Hill, Eucalyptus saligna Sm., Eucalyptus urophylla S.T.Blake, Eucalyptus viminalis Labill. and the hybrid E. grandis × E. urophylla) occupy approximately 20 million hectares, with high economic expressiveness, mainly in tropical and subtropical regions [1,2]. Brazil accounts for 38% of the world’s cultivated area, and Eucalyptus plantations continue to expand [3,4]. Concomitantly with the increase in planted areas, there was an increase in the release of pesticides.

According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Supply (MAPA), 173 formulated products are registered for Eucalyptus cultivation, with 3, 6, 15, and 76% of the products being acaricides, fungicides, insecticides, and herbicides, respectively [5]. The approval of new pesticides by MAPA requires knowledge of their isolated effects and possible interactions in tank mixtures.

Pesticide mixtures have been used to pest control simultaneously and reduce management costs [6,7]. Legalizing this practice occurred with the Normative Instruction No. 40 (11 October 2018), which establishes that professionals in the field can prescribe the technique, as long as the agronomic prescription contains the name of the products, incompatibility data, and the indicated culture [8]. The document also states that the recommendation will consider the available scientific information.

The risks associated with tank mixtures mainly concern physical and chemical incompatibility and knowledge of synergistic, antagonistic, and additive interactions among the compounds [9]. In addition, the pursuit of sustainable production in the forestry sector lacks research on the impact of pesticide mixtures [7].

Forest certification is a tool for sustainable forest management [10]. Forests certified with the “Forest Stewardship Council—FSC” system produced 23% of the world’s total volume of round wood in 2017 [11]. Within the FSC system is the Pesticide Policy, with three main pillars: classifying chemical compounds as dangerous, restricted, or highly restricted; carrying out an environmental and social risk assessment, and monitoring the use and damage caused by pesticides [12].

Large amounts of pesticides on crops, alone or in mixtures, can cause resistance in agricultural and forestry areas. Thus, in addition to the risks of using these products related to their toxicity, another point that must be considered is the risk of selecting biotypes resistant to pesticides.

Resistance is the capacity acquired by a plant to survive the registered dose of a pesticide that, under normal conditions, would be efficient to control the other members of the same population. The repeated use of products with the exact mechanism of action to control pests, diseases or weeds, in the same crop cycle over the years, without adopting alternative management practices, is the main reason for selecting resistant biotypes in agronomic crops in Brazil. There are still no reports of cases of resistance in Brazilian forest areas. Still, the risk has already been reported, considering the number of pesticides used without the proper rotation of products [13].

Because of the expressive release of Eucalyptus crop pesticides, the risks associated with using tank mixtures, and the adoption of sustainable forest management practices, this review sought to verify the effects of pesticide mixtures registered for Eucalyptus and described for other crops.

2. Tank Mixing in Brazil

The operational costs of pesticide application are remarkably high [14], resulting in approximately 97% of farmers opting for the joint application of phytosanitary products [14]. For this, pesticides are combined directly in the spray tanks, reducing the entry of machines into the site and, consequently, the cost of application [15]. However, mixing in tanks must be done with care because not all pesticides are compatible. Mixing can alter the pH and electrical conductivity and cause physical incompatibility [16,17], reducing the culture’s productivity [18].

Until 2018, the responsibility for mixing agrochemicals rested solely with the farmer. However, the Normative Instruction No. 40 (12 October 2018), MAPA established criteria and procedures to recommend tank mixtures and their prescriptions by professionals in the field [8]. This is because prior knowledge of product compatibility is necessary to guarantee the method’s efficacy [17]. In addition, mixtures can cause harmful effects to the environment if they contaminate non-target organisms [19].

In addition to the isolated effects of pesticides, there are risks from the mixture of products, so the growing approval of pesticides in Brazil is a reason for warning. Pesticides classes and similar registrations reached 474 in 2019, more than 4 times 10 years earlier. One hundred and forty-nine pesticides released in Brazil are banned in the European Union [20]; among these, atrazine, and acephate are some of the best sellers in Brazil [21].

The Normative Instruction No. 112 (8 October 2018), MAPA identified Digitaria insularis, Digitaria horizontalis, Panicum maximum, Brachiaria decumbens, and Brachiaria brizantha as priority pests of phytosanitary and economic importance for Eucalyptus cultures. Normative Instruction No. 112 focuses on registering new herbicides for Eucalyptus spp. [22]. Consequently, the Brazilian market today has 133 commercial herbicide formulations registered for use in Eucalyptus, representing a 200% increase from those reported in 2015 [5,23].

There are 173 registered products in Eucalyptus culture, 76% of which belong to the herbicide class [5]. Accordingly, the possibilities of mixtures within this class are more significant than insecticides, fungicides, and acaricides. The registered herbicides have grown significantly in recent years, mainly because of the need to combat difficult species in Eucalyptus spp. [22].

Among the herbicides registered for Eucalyptus cultures, 32 products are used to control grasses, particularly Brachiaria spp. and Digitaria spp. (Table 1) [5]. In addition to isolated products, herbicide tank mixtures are used for broader weed control, but these mixtures are not always satisfactory. For instance, mixtures between glyphosate and atrazine are less effective in controlling Brachiaria regrowth than isolated products [24].

Reports on pesticide mixtures aimed at forest areas are scarce, but determining these mixtures’ effects when applied to crops may help guide management actions.

Table 1.

Herbicides registered for the Eucalyptus culture are recommended for grass control.

Table 1.

Herbicides registered for the Eucalyptus culture are recommended for grass control.

| Active Ingredient | Controlled Grass Species |

|---|---|

| Carfentrazone-ethyl (triazolinones) + clomazone (isoxazolidinones) | Digitaria horizontalis; Brachiaria plantaginea; Eleusine indica |

| Clethodim (cyclohexanediones) + Haloxyfop-P-methyl (aryloxyphenoxypropionates) | Digitaria insularis; Brachiaria decumbens; Panicum maximum; Digitaria horizontalis; Brachiaria brizantha |

| Clomazone (isoxazolidinones) | Digitaria horizontalis; Cynodon dactylon; Eleusine indica; Brachiaria plantaginea |

| Diuron (Ureas) + Sulfentrazone (triazolinones) | Brachiaria decumbens |

| Flumioxazin (N-phenylphthalimides) | Panicum maximum |

| Glufosinate-ammonium (Phosphinic acids) | Panicum maximum; Melinis minutiflora |

| Glyphosate (glycine) | Sorghum halepense; Andropogon bicornis; Andropogon leucostachyus; Avena sativa; Axonopus compressus; Brachiaria decumbens; Brachiaria plantaginea; Bromus catharticus; Cenchrus echinatus; Cynodon dactylon; Digitaria horizontalis; Digitaria insularis; Echinochloa crusgalli; Eleusine indica; Hyparrhenia rufa; Lolium multiflorum; Melinis minutiflora; Panicum cayennense; Panicum maximum; Paspalum conjugatum; Paspalum dilatatum; Paspalum maritimum; Paspalum maritimum; Paspalum urvillei; Pennisetum clandestinum; Rhynchelytrum repens; Saccharum officinarum; Setaria geniculata; Setaria poiretiana |

| Glyphosate-dimethylamine salt (glycine) | Sorghum halepense; Digitaria insularis; Andropogon bicornis; Andropogon leucostachyus; Avena sativa; Axonopus compressus; Brachiaria decumbens; Brachiaria plantaginea; Bromus catharticus; Cenchrus echinatus; Cynodon dactylon; Digitaria horizontalis; Echinochloa crusgalli; Eleusine indica; Guadua angustifolia; Hyparrhenia rufa; Lolium multiflorum; Melinis minutiflora; Panicum cayennense; Panicum maximum; Paspalum conjugatum; Paspalum dilatatum; Paspalum maritimum; Paspalum notatum; Paspalum paniculatum; Paspalum urvillei; Pennisetum clandestinum; Rhynchelytrum repens; Saccharum officinarum; Setaria geniculata; Setaria poiretiana |

| Glyphosate-ammonium (glycine) | Avena strigosa; Brachiaria brizantha; Brachiaria decumbens; Brachiaria plantaginea; Cenchrus echinatus; Cynodon dactylon; Digitaria horizontalis; Digitaria insularis; Echinochloa crusgalli; Eleusine indica; Lolium multiflorum; Panicum maximum; Panicum maximum; Paspalum conjugatum; Paspalum notatum; Paspalum paniculatum; Saccharum officinarum; Sorghum bicolor |

| Glyphosate-di-ammonium (glycine) | Brachiaria brizantha; Brachiaria decumbens; Brachiaria plantaginea; Cenchrus echinatus; Chloris polydactyla; Digitaria horizontalis; Digitaria insularis; Digitaria sanguinalis; Echinochloa colona; Echinochloa crusgalli; Eleusine indica; Oryza sativa; Panicum maximum; Saccharum officinarum |

| Glyphosate-isopropylammonium (glycine) | Cynodon dactylon; Digitaria horizontalis; Digitaria insularis; Echinochloa crusgalli; Eleusine indica; Hyparrhenia rufa; Lolium multiflorum; Melinis minutiflora; Oryza sativa; Panicum cayennense; Panicum maximum; Panicum maximum; Paspalum conjugatum; Paspalum dilatatum; Paspalum maritimum; Paspalum notatum; Paspalum paniculatum; Paspalum urvillei; Pennisetum clandestinum; Rhynchelytrum repens; Saccharum officinarum; Setaria geniculata; Setaria poiretiana; Sorghum halepense; Sorghum halepense; Andropogon bicornis; Andropogon leucostachyus; Avena sativa; Axonopus compressus; Brachiaria decumbens; Brachiaria plantaginea; Bromus catharticus |

| Glyphosate-isopropylammonium (glycine) + Glyphosate-potassium (glycine) | Brachiaria decumbens; Brachiaria plantaginea; Digitaria horizontalis; Eleusine indica; Cynodon dactylon |

| Glyphosate-potassium (glycine) | Brachiaria decumbens; Avena strigosa; Cenchrus echinatus; Cynodon dactylon; Digitaria horizontalis; Echinochloa crusgalli; Eleusine indica; Luziola peruviana; Oryza sativa; Pennisetum americanum; Saccharum officinarum; Brachiaria plantaginea |

| Haloxyfop-P-methyl (aryloxyphenoxypropionates) | Brachiaria brizantha; Brachiaria decumbens; Lolium multiflorum |

| Indaziflam (alkylazine) | Brachiaria decumbens; Brachiaria brizantha; Digitaria horizontalis; Panicum maximum; Digitaria insularis |

| Indaziflam (alkylazine) + Iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium (sulfonylureas) | Brachiaria decumbens |

| Isoxaflutole (isoxazoles) | Cenchrus echinatus; Eleusine indica; Brachiaria plantaginea; Brachiaria decumbens; Panicum maximum; Digitaria horizontalis |

| Isoxaflutole (isoxazoles) | Brachiaria plantaginea; Panicum maximum; Brachiaria decumbens; Eleusine indica; Cenchrus echinatus; Digitaria horizontalis |

| Oxyfluorfen (diphenylethers) | Digitaria horizontalis; Cenchrus echinatus; Eleusine indica |

| Pendimethalin (chloroacetamides) | Panicum maximum; Brachiaria decumbens; Digitaria horizontalis; Brachiaria plantaginea |

| Pyroxasulfone (chloroacetamides) | Brachiaria plantaginea; Brachiaria decumbens; Digitaria horizontalis; Panicum maximum |

| Pyroxasulfone (pyrazol) + Flumioxazin (N-phenylphthalimides) | Cenchrus echinatus; Digitaria horizontalis; Brachiaria decumbens; Brachiaria plantaginea; Panicum maximum |

| S-Metolachlor (chloroacetamides) + glyphosate (glycine) | Panicum maximum; Brachiaria decumbens |

| Sulfentrazone (triazolinones) | Brachiaria plantaginea; Pennisetum setosum; Panicum maximum; Digitaria horizontalis; Cenchrus echinatus; Brachiaria decumbens; Echinochloa crusgalli; Eleusine indica |

| Sulfentrazone (triazolinones) | Pennisetum setosum; Panicum maximum; Eleusine indica; Echinochloa crusgalli; Digitaria horizontalis; Cenchrus echinatus; Brachiaria plantaginea; Brachiaria decumbens; Echinochloa crusgalli |

Source: AGROFIT, 2021 [5].

3. Forest Stewardship Council

The forest certification system Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) is one of the most internationally recognized in the sector [25] to assure consumers that timber products originate from well-managed forests that respect the principles and criteria of environmental, social, and economic aspects focused on sustainability [26]. In Brazil, the planted area certified by the FSC is 1.5 million hectares [27]. Some of the biggest non-compliance problems for FSC certification are environmental impact and risk monitoring and evaluation [28].

The Pesticide Policy is part of the FSC’s Principles and Criteria for forest certification and has been revised to incorporate a risk-based approach to pesticide use [12]. In this case, the danger of the active ingredient is considered and the circumstances under which chemical pesticides can be used [12]. The Pesticide Policy is based on the following considerations: (a) hazardous pesticides are identified and categorized as prohibited, highly restricted, or restricted according to their degree of danger; (b) integrated pest management identifies the need to use a permitted chemical pesticide as a measure of last resort, an environmental and social risk assessment (ARAS) is carried out at different levels to identify the nature and degree of risk together with mitigation measures and monitoring requirements; (c) the policy highlights the importance of repairing and compensating for any damage to environmental values and human health and of monitoring both pesticide use and the impact of the policy itself [12].

The FSC certification policy restricts the use of pesticides that are dangerous to human health and the environment, classified as prohibited products, highly restricted products, or restricted products [12] (Table 2 and Table 3). There are 48 products prohibited in certified areas, including acetochlor, alachlor, captafol, carbofuran, DDT, paraquat, and others [12]. The highly restricted product list comprises 120 deltamethrin, bromoxynil, carbaryl, diquat, isoprocarb, and permethrin [12]. The list of local products is even longer with 221 pesticides, some widely used in Brazil, such as 2,4-D, atrazine, diuron, ammonium glufosinate, glyphosate, imidacloprid, and picloram [12].

The growing awareness of the world population on humanity’s future has led to the search for innovations that make the means of production more sustainable in various sectors of society [29]. Accordingly, FSC certification is a tool for enhancing eco-labels, as it seeks to improve awareness of environmental impacts, increase stakeholder participation, and improve eco-efficiency [30]. Discussions of the FSC’s role in the sustainable forest industry are centered around the possibility of playing a role in forest governance to promote and articulate its potential contributions [28].

Table 2.

List of pesticides registered for Eucalyptus cultivation in Brazil and their classification by the Forest Stewardship Council—FSC.

Table 2.

List of pesticides registered for Eucalyptus cultivation in Brazil and their classification by the Forest Stewardship Council—FSC.

| Herbicide | Toxicity Class * | PAM ** | FSC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | |||

| 2,4-D-triethanolamine + picloram-triethanolamine | 5 | AM | Restricted |

| Carfentrazone-ethyl | 5 | IPO | Unclassified |

| Clethodim | 5 | IACC | Unclassified |

| Clomazone | 5 | IMA | Unclassified |

| Chlorimuron-ethyl | 5 | IAS | Unclassified |

| Diuron | 5 | PSII I | Restricted |

| Flumioxazin | 5 | IPO | Restricted |

| Fluroxypyr-meptyl + triclopyr-butotyl | 4 | AM | Unclassified |

| Glufosinate-ammonium | 5 | IGS | Restricted |

| Glyphosate | 5 | IESPS | Restricted |

| Haloxyfop-P-methyl | 4 | IACC | Restricted |

| Indaziflam + iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium | 5 | ICS + IAS | Unclassified |

| Isoxaflutole | 5 | IHPD | Restricted |

| Oxyfluorfen | 4 | IPO | Restricted |

| Pendimethalin | 4 | IMA | Restricted |

| Pyroxasulfone | 5 | VLFASI | Unclassified |

| Saflufenacil | 5 | IPO | Unclassified |

| S-Metolachlor | 4 | VLFASI | Unclassified |

| Sulfentrazone | 5 | IPO | Unclassified |

| Insecticide | Toxicity class * | PAM ** | FSC |

| Classification | |||

| Acetamiprid | 4 | AA | Restricted |

| Bifenthrin | 2 | SCM | Highly restricted |

| Bifenthrin + acetamiprid | 3 | SCM + AA | Restricted |

| Carbosulfan | 2 | IEA | Prohibited |

| Chlorfenapyr | 4 | UOPDPG | Highly restricted |

| Deltamethrin | 4 | SCM | Highly restricted |

| Etofenprox | 4 | SCM | Restricted |

| Fipronil | 3 | GAA | Restricted |

| Imidacloprid | 4 | AA | Restricted |

| Lufenuron | 5 | ICB | Restricted |

| Tebufenozide | Unclassified | EA | Unclassified |

| Teflubenzuron | Unclassified | ICB | Restricted |

| Thiamethoxam | 5 | AA | Unclassified |

| Zeta-cypermethrin + bifenthrin | 3 | SCM | Highly restricted |

| Acaricide | Toxicity class * | PAM ** | FSC |

| Classification | |||

| Bifenthrin | 2 | SCM | Highly restricted |

| Carbosulfan | 2 | IEA | Prohibited |

| Chlorfenapyr | 4 | UOPDPG | Highly restricted |

| Chlorfenapyr | 4 | UOPDPG | Highly restricted |

| Fungicide | Toxicity class * | PAM ** | FSC |

| Classification | |||

| Acibenzolar-S-Methyl | Unclassified | PDI | Unclassified |

| Azoxystrobin + difenoconazol | 5 | RI + ISB | Unclassified |

| Cyproconazol | 5 | ISB | Highly restricted |

| Difenoconazole | 4 | ISB | Unclassified |

| Mancozeb | 5 | MA | Restricted |

| Metconazole | 5 | ISB | Unclassified |

| Metiram + pyraclostrobin | 4 | MA + RI | Restricted |

| Pyraclostrobin | 4 | RI | Restricted |

| Tebuconazole | 5 | ISB | Unclassified |

| Trifloxystrobin | 5 | RI | Restricted |

* Toxicity class according to the manufacturers: (1) extremely toxic, (2) highly toxic, (3) moderately toxic, (4) slightly toxic, and (5) unlikely to cause acute harm. ** Pesticide Action Mechanism (PAM). Source: AGROFIT, 2021; FSC, 2019 [5,12].

Table 3.

List of pesticide action mechanisms.

Table 3.

List of pesticide action mechanisms.

| Pesticide Action Mechanism (PAM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HERBICIDES | Inhibition of Cellulose Synthesis—ICS | FUNGICIDES | Sodium Channel Modulators—SCM |

| Auxin Mimics—AM | Inhibition of Hydroxyphenyl Pyruvate Dioxygenase—IHPD | Plant defense inducers—PDI | Inhibitors of the Enzyme Acetylcholinesterase—IEA |

| Inhibition of Acetoacetate Synthase—IAS | Very Long-Chain Fatty Acid Synthesis inhibitors—VLCFASI | Inhibition of sterol biosynthesis—ISB | Gamma-AminoButyric Acid Agonist—GAA |

| PSII inhibitors—PSII I | ACARICIDES | Multi-site Activity—MA | Inhibitors of the Chitin Biosynthesis—ICB |

| Inhibition of Protoporphyrinogen Oxidase—IPO | Sodium Channel Modulators—SCM | Respiratory Inhibitor—RI | Ecdysteroid Agonists—EA |

| Inhibition of Glutamine Synthetase—IGS | Inhibitors of the Enzyme Acetylcholinesterase—IEA | INSECTICIDES | Uncouplers of oxidative phosphorylation via disruption of the proton gradient—UOPDPG |

| Inhibition of Enolpyruvyl Shikimate Phosphate Synthase—IESPS | Uncouplers of oxidative phosphorylation via disruption of the proton gradient—UOPDPG | Acetylcholine Agonist—AA | |

| Inhibition of Acetyl CoA Carboxylase—IACC | |||

Source: AGROFIT, 2021 [5].

4. Effects of Pesticide Tank Mixtures

Mixing pesticides in a spray tank is a common technique among farmers, but some unexpected effects can occur depending on the type of interaction between the products. Exchanges can be additive when the mixing efficiency of the products is similar to the application of each product; synergistic when the mixture of products presents better results than the isolated application, and antagonistic when the mix of products is worse than each one applied [31].

In agricultural systems, interactions among pesticide mixtures have been established [6], but there is a lack of reports in the forestry sector, more in Eucalyptus crops. Therefore, information on pesticides used in crops also recorded for Eucalyptus can be a viable solution to fill this gap.

In herbicide mixtures, 72% of those found in the literature include glyphosate. Mixtures with glyphosate were the most cited as antagonistic, corresponding to 12 of the 19 reported (Table 4). Among the alternatives for the efficient control of weeds, mixtures of glyphosate with ethyl carfentrazone, clethodim, chlorimuron-ethyl, fluazifop-butyl, flumioxazin, haloxyfop, quizalofop, and saflufenacil had synergistic effects (Table 4). Among these, glyphosate, flumioxazin, and haloxyfop are restricted by FMC [12] (Table 2), while the others are not classified in any risk category.

The challenges of tank mixtures go beyond the combination of active ingredients, as the same mixtures can have different results, as observed for glyphosate plus 2,4-D (Table 4). These differences may be related to edaphoclimatic variations, dosages used, or species controlled, allowing antagonistic and synergistic interactions for the same product combination.

Table 4.

Results of the interaction of herbicide mixtures registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop, when used in other crops.

Table 4.

Results of the interaction of herbicide mixtures registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop, when used in other crops.

| Herbicide 1 | Herbicide 2 | Herbicide 3 | Crop/Weed | Interaction | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,4-D | Clethodim | Digitaria insularis | Antagonistic | [32] | |

| Quizalofop | Additive | ||||

| Quizalofop | Antagonistic | ||||

| Atrazine | Metolachlor | Oryza sativa | Synergistic | [33] | |

| Clomazone | Alachlor | Gossypium hirsutum | Additive | [34] | |

| Synergistic | [35] | ||||

| Diuron | Additive | [36] | |||

| Oxyfluorfen | Synergistic | ||||

| Trifluralin | Additive | ||||

| Diuron | Additive | ||||

| Fluazifop-butyl | 2,4-D | Zea mays | Antagonistic | [36] | |

| Glyphosate | Additive | ||||

| Glyphosate + 2,4-D | Additive | ||||

| Fluazifop-p-butyl | Flumioxazin | Manihot esculenta | Synergistic | [37] | |

| Isoxaflutole | Synergistic | ||||

| Glufosinate-ammonium | Saflufenacil | Amaranthus palmeri | Synergistic | [38] | |

| Glyphosate | 2,4-D | Ricinus communis | Synergistic | [39] | |

| Commelina benghalensis | Additive | [40] | |||

| Cyperus rotundus | Additive | [41] | |||

| Eucalyptus spp. | Synergistic | [42] | |||

| Glyphosate | 2,4-D | Zea mays | Antagonistic | [43] | |

| Atrazine | Urochloa plantaginea | Antagonistic | [24] | ||

| Flumioxazin | Additive | ||||

| Carfentrazone-Ethyl | Commelina benghalensis | Synergistic | [40] | ||

| Manihot esculenta | Additive | [44] | |||

| Ipomoea hederifolia | Synergistic | [45] | |||

| Additive | [46] | ||||

| Eucalyptus spp. | Additive | [47] | |||

| Commelina benghalensis | Antagonistic | [48] | |||

| Clethodim | Digitaria insularis | Additive | [49] | ||

| Leptochloa virgata | Synergistic | [50] | |||

| Bidens pilosa | Antagonistic | ||||

| Digitaria insularis | Synergistic | [51] | |||

| Lolium multiflorum | Additive | [52] | |||

| Clomazone | Manihot esculenta | Additive | [44] | ||

| Chlorimuron-ethyl | Commelina benghalensis | Additive | [53] | ||

| Crotalaria ochroleuca | Antagonistic | [54] | |||

| Glycine max | Additive | [55] | |||

| Flumioxazin | Synergistic | ||||

| Commelina benghalensis | Additive | [56] | |||

| Manihot esculenta | Additive | [44] | |||

| Fluazifop-butyl | Cynodon dactylon | Synergistic | [57] | ||

| Leptochloa virgata | Synergistic | [50] | |||

| Glyphosate | Fluazifop-butyl | Bidens pilosa | Antagonistic | [50] | |

| Lolium multiflorum | Additive | [52] | |||

| Flumioxazin | Manihot esculenta | Additive | [44] | ||

| Urochloa plantaginea | Synergistic | [24] | |||

| Commelina benghalensis | Antagonistic | [48] | |||

| Haloxyfop | Zea mays | Additive | [58] | ||

| Cynodon dactylon | Synergistic | [57] | |||

| Digitaria insularis | Synergistic | [59] | |||

| 2,4-D | Antagonistic | ||||

| Additive | [49] | ||||

| Metribuzin | Manihot esculenta | Additive | [44] | ||

| Cyperus rotundus | Antagonistic | [41] | |||

| Oxyfluorfen | Commelina benghalensis | Antagonistic | [48] | ||

| Quizalofop | Lolium multiflorum | Synergistic | [52] | ||

| Saflufenacil | Commelina benghalensis | Synergistic | [40] | ||

| Ricinus communis | Synergistic | [60] | |||

| Brachiaria decumbens | Additive | [61] | |||

| Conyza bonariensis | Synergistic | [62] | |||

| Ipomoea hederifolia | Synergistic | [45] | |||

| Amaranthus hybridus | Antagonistic | [63] | |||

| Additive | [46] | ||||

| Conyza bonariensis | Synergistic | [64] | |||

| Lolium multiflorum | Synergistic | [52] | |||

| Glyphosate | Sulfometuron | Glycine max | Antagonistic | [65] | |

| Glyphosate-ammonium | Clethodim | Digitaria insularis | Additive | [66] | |

| Haloxyfop | Synergistic | ||||

| Quizalofop | Additive | ||||

| Glyphosate-isopropylammonium | Clethodim | Additive | |||

| Haloxyfop | Synergistic | ||||

| Quizalofop | Synergistic | ||||

| Glyphosate-potassium | Clethodim | Synergistic | |||

| Haloxyfop | Synergistic | ||||

| Quizalofop | Additive | ||||

| Carfentrazone | Oryza sativa | Additive | [67] | ||

| Saflufenacil | Additive | ||||

| Isoxaflutole | Acetolachlor | Zea mays | Additive | [68] | |

| Oxyfluorfem | Haloxyfop | Digitaria insularis | Antagonistic | [49] | |

| Quizalofop | Carfentrazone | Oryza sativa | Additive | [67] | |

| Quizalofop | Linuron | Vigna unguiculata | Synergistic | [69] | |

| Quizalofop | Saflufenacil | Oryza sativa | Synergistic | [67] | |

| Saflufenacil | Clomazone | Euphorbia heterophylla | Synergistic | [70] | |

| Saflufenacil | Clomazone | Oryza sativa | Additive | [71] |

In most cases, mixtures between insecticides have synergistic interactions with greater pest control (Table 5). Only bifenthrin combined with acephate and imidacloprid had an antagonistic effect on the control of Lygus lineolaris Palisot de Beauvois, 1818 (Hemiptera: Miridae) [72]. The antagonistic effect of bifenthrin, combined with its highly restricted classification by the FMC [12], is the basis for avoiding its mixtures.

Insecticides mixed with herbicides exhibited additive and synergistic interactions. Mixtures such as glyphosate plus acephate, atrazine plus novaluron, and 2,4-D with chlorpyrifos-ethyl, fipronil, methomyl, and novaluron, performed well (Table 6). Acaricides mixed with insecticides exhibit additive and antagonistic interactions. Mixtures of spirodiclofen with lambda-cyhalothrin + thiamethoxam, phosmet, and thiamethoxam can be used to reduce application costs without enhancing pest control (Table 7).

Insecticides mixed with fungicides have an additive effect (Table 8), except for the combination of chlorothalonil with abamectin. The fungicide addition caused reduced efficacy against Thrips tabaci Lindeman, 1889 (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) [73].

The interactions of mixtures among the analyzed fungicides were not negative, and the product combination enhanced the antifungal action of the product. Synergistic effects were obtained by combining propiconazole with iprodione, vinclozolin, mancozeb, and carbendazim with folpet (Table 9). However, only mancozeb is registered for Eucalyptus in Brazil and has a restricted classification for use in areas certified by the FSC [5,12]. When combined with herbicides, fungicides do not result in antagonistic interactions (Table 10) and can be applied together to reduce operating costs. However, 40 of the mixtures reported as additives use glyphosate, which is highly restricted by the FSC [12].

Table 5.

The interaction of insecticide mixtures registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop when used in other crops.

Table 5.

The interaction of insecticide mixtures registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop when used in other crops.

| Insecticide 1 | Insecticide 2 | Crop/Insects | Interaction | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bifenthrin | Acephate | Lygus lineolaris | Antagonistic | [72] |

| Dicrotophos | Synergistic | |||

| Imidacloprid | Antagonistic | |||

| Thiamethoxam | Synergistic | |||

| Deltamethrin | Dichlorvos | Glycine max (A. gemmatalis) | Synergistic | [74] |

| Imidacloprid | Acephate | Apis mellifera | Additive | [75] |

| Cyhalothrin | Additive | |||

| Oxamyl | Synergistic | |||

| Thiodicarb | Sorghum bicolor | Synergistic | [76] | |

| Lambda-cyhalothrin | Chlorantraniliprole | Anthonomus grandis | Synergistic | [77] |

| Lufenuron | Profenofos | Glycine max (A. gemmatalis) | Synergistic | [78] |

| Spiromesifen | Imidacloprid | Bemisia tabaci | Synergistic | [79] |

| Thiamethoxam | Chlorantraniliprole | Myzus persicae | Synergistic | [80] |

| Lambda-Cyhalothrin | Synergistic |

Table 6.

The interaction of mixtures of herbicides and insecticides registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop when used in other crops.

Table 6.

The interaction of mixtures of herbicides and insecticides registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop when used in other crops.

| Herbicide 1 | Herbicide 2 | Insecticide | Crop/Weed | Interaction | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,4-D | Chlorpyrifos-ethyl | Zea mays | Synergistic | [58] | |

| Fipronil | Saccharum officinarum | Synergistic | [81] | ||

| Methomyl | Zea mays | Synergistic | [58] | ||

| Novaluron | Synergistic | ||||

| Permethrin | Additive | ||||

| Atrazine | Chlorpyrifos-ethyl | Additive | |||

| Lufenuron | Additive | [82] | |||

| Methomyl | Additive | [58] | |||

| Additive | [82] | ||||

| Novaluron | Synergistic | [58] | |||

| Permethrin | Additive | ||||

| Glufosinate-ammonium | 2,4-D | Lambda-cyhalothrin | Glycine max | Additive | [83] |

| Additive | |||||

| Glyphosate | Acephate | Gossypium hirsutum | Synergistic | [84] | |

| Carbosulfan | Additive | ||||

| Endosulfan | Additive | ||||

| Imidacloprid | Additive | ||||

| 2,4-D | Lambda-cyhalothrin | Glycine max | Additive | [83] | |

| Additive | |||||

| Glyphosate | Lambda-cyhalothrin | Gossypium hirsutum | Additive | [84] | |

| Sulfentrazone | Imidacloprid | Allium cepa | Additive | [51] |

Table 7.

The interaction of insecticide and acaricide mixtures registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop when used in other crops.

Table 7.

The interaction of insecticide and acaricide mixtures registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop when used in other crops.

| Insecticide | Acaricide | Crop/Insect | Interaction | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bifenthrin | Spirodiclofen | Citrus | Antagonistic | [85] |

| Cypermethrin | Antagonistic | |||

| Imidacloprid | Diaphorina citri | Antagonistic | [86] | |

| Citrus | Antagonistic | [86] | ||

| Lambda-cyhalothrin + thiamethoxam | Diaphorina citri | Additive | [86] | |

| Phosmet | Additive | |||

| Citrus | Antagonistic | [85] | ||

| Thiamethoxam | Diaphorina citri | Additive | [86] |

Table 8.

Results of the interaction of mixtures of fungicides and insecticides registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop, when used in other crops.

Table 8.

Results of the interaction of mixtures of fungicides and insecticides registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop, when used in other crops.

| Fungicide | Insecticide | Crop/Insect | Interaction | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azoxystrobin + benzovindiflupyr | Methomyl | Glycine max | Additive | [87] |

| Azoxystrobin + cyproconazole | Triflumuron | Spodoptera frugiperda | Additive | [88] |

| Azoxystrobin | Abamectin | Thrips tabaci | Additive | [73] |

| Chlorothalonil | Abamectin | Thrips tabaci | Antagonistic | [73] |

| Iprodione | Additive | |||

| Mancozeb | Additive | |||

| Pyraclostrobin + fluxapyroxad | Lambda-Cyhalothrin | Glycine max | Additive | [89] |

| Tetraconazole | Imidacloprid | Apis mellifera | Synergistic | [75] |

| Tebuconazole | Thiacloprid | Aphelinus abdominalis | Synergistic | [90] |

| Trifloxystrobin + propiconazole | Methomyl | Glycine max | Additive | [87] |

Table 9.

Results of the interaction of fungicide mixtures registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop, when used in other crops.

Table 9.

Results of the interaction of fungicide mixtures registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop, when used in other crops.

| Fungicide 1 | Fungicide 2 | Fungus | Interaction | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mancozeb | Carbendazim | Colletotrichum acutatum | Synergistic | [91] |

| Folpet | Synergistic | |||

| Propiconazole | Chlorothalonil | Sclerotinia homeocarpa | Additive | [92] |

| Iprodione | Synergistic | |||

| Vinclozolin | Synergistic |

Table 10.

The interaction of mixtures of herbicides and fungicides registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop when used in other crops.

Table 10.

The interaction of mixtures of herbicides and fungicides registered in Brazil for the Eucalyptus crop when used in other crops.

| Herbicide 1 | Herbicide 2 | Fungicide | Crop/Weed | Interaction | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,4-D | Azoxystrobin + propiconazole | Triticum aestivum | Additive | [93] | |

| Propiconazole + trifloxystrobin | Additive | ||||

| Glufosinate | Pyraclostrobin | Glycine max | Additive | [83] | |

| Glyphosate | Additive | ||||

| Triticum aestivum | Additive | [93] | |||

| Tebuconazole | Synergistic | ||||

| Glufosinate | Pyraclostrobin | Glycine max | Additive | [83] | |

| Glyphosate | Azoxystrobin | Panicum texanum | Additive | [94] | |

| Pyraclostrobin | Additive | ||||

| Glycine max | Additive | [83] | |||

| Tetraconazol | Panicum texanum | Additive | [94] | ||

| Additive |

5. Perspectives for the Forestry Sector Regarding Tank Mixtures

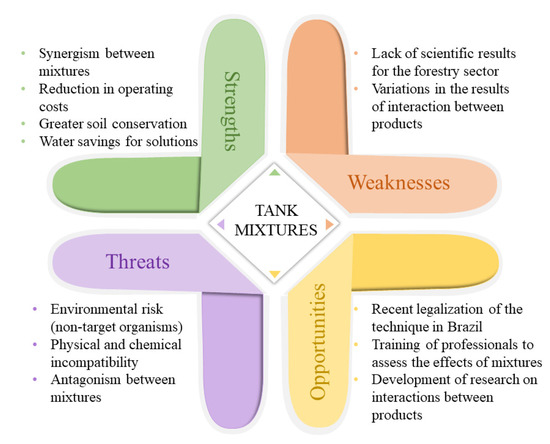

The SWOT analysis addresses strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. It is a tool for strategic planning [95] and can be used to summarize the current state of tank mixing techniques in the forest sector (Figure 1). Mixing pesticides in tanks is a common technique among farmers, and results are available for crops. This technique in the forestry sector is still developing, but it can expand given its advantages. Based on advances in Brazilian legislation on the use of pesticides and the evolution of phytosanitary practices, tank mixtures can provide several benefits in the management of pests, diseases, and weeds in Eucalyptus cultures, such as reduction of operating costs and a decrease in the entry of machines in the area. Together, this results in more significant soil conservation, saving water for solutions, and, in some cases, enhancing pesticide efficacy.

Figure 1.

The SWOT analysis summarizes the current status of the tank mixing technique in the forestry sector.

Moreover, pesticide classification by the FSC contributes to the intended use of the products, considering the risks to the environment and human health. At the same time, product mixtures considered to be of restricted use, regardless of their category as listed in this review, can be applied through environmental and social risk analysis (ARAS), which makes this paper an essential tool for scientific, technical consultation.

Some challenges are related to the lack of proven results for efficient mixtures of phytosanitary products in the forestry sector. In addition to targeting the sector’s exclusive pesticides, future studies should consider mixtures with fertilizers. The effect variation indicates the need for specific research with foresters, considering different climate and soil conditions and control species. Furthermore, the results reported may vary depending on the applied dosages and non-compliance with the application technology. The lack of trained professionals in the field to assess the effects of mixtures limits the use of this technique. Therefore, practical human resources training and evaluation of results among pesticide mixtures when the method is expanding are essential to direct the actions of forestry companies in Brazil.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M.B. and J.B.d.S.; methodology, T.S.D., I.G.C., M.L.F.L. and J.M.C.; validation, D.V.S., A.P.B.J. and F.D.d.S.; investigation, G.M.B.; resources, D.V.S., J.B.d.S.; T.S.D., I.G.C., M.L.F.L. and J.M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M.B.; writing—review and editing, T.S.D. and F.D.d.S.; supervision, J.B.d.S.; project administration, J.B.d.S. and D.V.S.; funding acquisition, D.V.S. and J.B.d.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the funders, Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES—Finance Code 001), Minas Gerais State Research Support Foundation (FAPEMIG—PPM-00664-17), and National Council for Scientific Development and Tecnológico (CNPq—311720/2019-6).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Da Silva, P.H.M.; Junqueira, L.R.; Araujo, M.J.; Wilcken, C.F.; Moraes, M.L.T.; De Paula, R.C. Susceptibility of eucalypt taxa to a natural infestation by Leptocybe invasa. New For. 2019, 51, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, W.R.C.; da Costa, Y.K.S.; Carbonari, C.A.; Duke, S.O.; Alves, P.L.D.C.A.; de Carvalho, L.B. Growth, morphological, metabolic and photosynthetic responses of clones of eucalyptus to glyphosate. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 470–471, 118218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. 2019. Available online: https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/pesquisa/pevs/tabelas (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Bassaco, M.V.M.; Motta, A.; Pauletti, V.; Prior, S.A.; Nisgoski, S.; Ferreira, C.F. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium requirements for Eucalyptus urograndis plantations in southern Brazil. New For. 2018, 49, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AGROFIT. Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento: Sistema de Agrotóxicos e Fitossanitários. 2020. Available online: http://agrofit.agricultura.gov.br/agrofit_cons/principal_agrofit_cons (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Gandini, E.M.M.; Costa, E.S.P.; Santos, J.; Soares, M.A.; Barroso, G.M.; Corrêa, J.M.; Carvalho, A.G.; Zanuncio, J.C. Compatibility of pesticides and/or fertilizers in tank mixtures. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilaqua, F.; Sachett, A.; Chitolina, R.; Garbinato, C.; Gasparetto, H.; Marcon, M.; Mocelin, R.; Dallegrave, E.; Conterato, G.; Piato, A.; et al. A mixture of fipronil and fungicides induces alterations on behavioral and oxidative stress parameters in zebrafish. Ecotoxicology 2019, 29, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Instrução Normativa Nº 40 de 11 de Outubro de 2018. Diário Oficial da União: Seção 1. p. 3, 15 de Outubro de 2018. Available online: https://www.jusbrasil.com.br/diarios/212979587/dou-secao-1-15-10-2018-pg-3 (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Petter, F.; Segate, D.; Pacheco, L.; Almeida, F.; Neto, F.A. Incompatibilidade física de misturas entre herbicidas e inseticidas. Planta Daninha 2012, 30, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmakar, S.; Oli, B.N.; Joshi, N.R.; Maraseni, T.N.; Atreya, K. Forest Carbon Storage and Species Richness in FSC Certified and Non-certified Community Forests in Nepal. Small-Scale For. 2021, 20, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Forests 2018—Forest Pathways to Sustainable Development. 2018. Rome. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/I9535EN/ (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- FSC—Forest Stewardship Council. Política de Pesticidas do FSC. Available online: https://br.fsc.org/pt-br/novidades/id/1168 (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Barroso, G.M.; da Silva, R.S.; Mucida, D.P.; Borges, C.E.; Ferreira, S.R.; dos Santos, J.C.B.; dos Santos, J.B. Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Digitaria insularis: Risk Analysis of Areas with Potential for Selection of Glyphosate-Resistant Biotypes in Eucalyptus Crops in Brazil. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrue, A. Influência da mistura em tanque de inseticidas e fungicidas na cultura da soja. In Proceedings of the XVI Simposio de Ensino, Pesquisa e Extensão, Santa Maria, Brazil, 3–5 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gazziero, D. Misturas de agrotóxicos em tanque nas propriedades agrícolas do Brasil. Planta Daninha 2015, 33, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, D.J.; Ferreira, M.D.C.; Fenólio, L.G. Compatibilidade entre acaricidas e fertilizantes foliares em função de diferentes águas no controle do ácaro da leprose dos citros Brevipalpus phoenicis. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2013, 35, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Petter, F.A.; Segate, D.; de Almeida, F.A.; Neto, F.A.; Pacheco, L.P. Incompatibilidade física de misturas entre inseticidas e fungicidas. Comun. Sci. 2013, 4, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.; Freitas, F.; Ferreira, L.; Jakelaitis, A. Efeitos de mistura de herbicida com inseticida sobre a cultura do milho, as plantas daninhas e a lagarta-do-cartucho. Planta Daninha 2005, 23, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Q.; Qian, Y. Assessing joint toxicity of four organophosphate and carbamate insecticides in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) using acetylcholinesterase activity as an endpoint. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2015, 122, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombardi, L.M. Geografia do Uso de Agrotóxicos no Brasil e Conexões com a União Europeia; FFLCH-USP: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IBAMA. Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis. Available online: http://ibama.gov.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=594&Itemid=54 (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Brasil. Instrução Normativa Nº 112 de 15 de Outubro de 2018. Diário Oficial da União: Seção 1. p. 4, 15 de Outubro de 2018. Available online: https://www.jusbrasil.com.br/diarios/212979560/dou-secao-1-15-10-2018-pg-4 (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Goulart, I.D.R.; Santarosa, E.; Porfirio-da-silva, V. Herbicidas registrados para a cultura do eucalipto. Embrapa Florestas-Comunicado Técnico (INFOTECA-E). 2015. Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/handle/doc/1023661 (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Ratier, F.J.P.; Guerra, N.; de Oliveira Neto, A.M. Efeito de misturas de herbicidas na dessecação pré-semeadura e no desenvolvimento inicial do milho safrinha. Campo Digit. 2015, 10, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, M.-G.; Drigo, I.G. Shaping the implementation of the FSC standard: The case of auditors in Brazil. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 90, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.A.; Davis, S.R. Forest certification, institutional capacity, and learning: An analysis of the impacts of the Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 52, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBÁ—Indústria Brasileira de Árvores. Relatório 2019. Available online: https://iba.org/datafiles/publicacoes/relatorios/iba-relatorioanual2019.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Rafael, G.C.; Fonseca, A.; Jacovine, L.A.G. Non-conformities to the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) standards: Empirical evidence and implications for policy-making in Brazil. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 88, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, B.S.; Ţîrcă, D.M. Innovations for sustainable development: Moving toward a sustainable future. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, A.; Palmer, C. A qualitative meta-synthesis of the benefits of eco-labeling in developing countries. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 127, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K. Scope and relevance of using pesticide mixtures in crop protection: A critical review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. 2014, 2, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, H.L.L.; Sambatti, V.C.; Dalazen, G. Sourgrass control in response to the association of 2,4-d to ACCase inhibitor herbicides. Biosci. J. 2020, 36, 1126–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.T.; Kröger, R. Effect of Three Insecticides and Two Herbicides on Rice (Oryza sativa) Seedling Germination and Growth. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2010, 59, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, H.A.; Barroso, A.L.L.; Oliveira Júnior, R.S.; Constantin, J.; Dan, L.G.M.; Braz, G.B.P.; D’Avila, R.P. Selectivity of clomazone applied alone or in tank mixtures to cotton. Planta Daninha 2011, 29, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Arantes, J.G.Z.; Takano, H.K.; Constantin, J.; Júnior, R.S.D.O.; Braz, G.B.P.; Gemelli, A. Avaliação da seletividade do clomazone isolado ou em mistura para o algodoeiro. Agrarian 2017, 10, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alvarenga, D.R.; Teixeira, M.F.F.; De Freitas, F.C.L.; Paiva, M.C.G.; Carvalho, M.R.N.; Gonçalves, V.A. Interações Entre Herbicidas No Manejo Do Milho Rr® Voluntário. Rev. Bras. Milho E Sorgo 2018, 17, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lima, A.C.; Do Rosário Silva, L.; Pontes, V.B.; De Sousa, A.C.M.; Viana, R.G. Fitotoxidez E Trocas Gasosas Na Mandioca Submetida A Aplicação De Misturas De Herbicidas Em Pós Emergência. 2018. Available online: https://cointer.institutoidv.org/inscricao/pdvagro/uploadsAnais/FITOTOXIDEZ-E-TROCAS-GASOSAS-NA-MANDIOCA-SUBMETIDA-A-APLICA%C3%87%C3%83O-DE-MISTURAS-DE-HERBICIDAS-EM-P%C3%93S-EMERG%C3%8ANCIA.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Takano, H.K.; Beffa, R.; Preston, C.; Westra, P.; Dayan, F.E. Glufosinate enhances the activity of protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibitors. Weed Sci. 2020, 68, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foloni, J.S.S.; Hirata, A.C.S.; Pereira, D.N.; De Carvalho, M.L.M.; Casavechia, D. Dessecação química em pré-colheita da mamona. Rev. Ceres 2011, 58, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, D.; Santana, D.C.; de Souza, G.S.F.; Bagatta, M.V.B. Manejo químico de espécies de trapoeraba com aplicação isolada e em mistura de diferentes herbicidas. Rev. Caatinga 2012, 25, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Heck, T.; Cinelli, R.; Polito, R.A.; Ribas, J.L.; Bagnara, F.; Hahn, A.M.; Nunes, A.L. A importância dos herbicidas residuais no controle da tiririca. Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 65147–65163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A., Jr.; Freitas, F.; Santos, I.; Silva, D.; La Cruz, R.A.-D.; Ferreira, L. Use of Fertiactyl Pos® for Protection of Eucalyptus Plants Subjected to Herbicide Drift. Planta Daninha 2020, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, N.; Shropshire, C.; Sikkema, P.H. Tank mixture of glyphosate with 2,4-D accentuates 2,4-D injury in glyphosate-resistant corn. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2018, 98, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, N.V.; Arrúa, M.M.; Sontag, D.A.; De Andrade, D.C.; Júnior, J.B.D. Seletividade de herbicidas residuais e da mistura com glyphosate aplicados após a poda da mandioca ‘Fécula Branca’. Rev. Bras. Herbic. 2014, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Agostineto, M.C.; De Carvalho, L.B.; Ansolin, H.H.; De Andrade, T.C.G.R.; Schmit, R. Sinergismo de misturas de glyphosate e herbicidas inibidores da PROTOX no controle de corda-de-viola. Rev. Ciências Agroveterinárias 2016, 15, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Oliveira, W. Eficácia do Glifosato em Mistura com Carfentrazona e Saflufenacil em Dessecação Pré-Plantio. 2019. Available online: https://repositorio.ifgoiano.edu.br/handle/prefix/1271 (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Santos, S.A.; Tuffi-Santos, L.D.; Alfenas, A.C.; Faria, A.T.; Sant’anna-Santos, B.F. Differential Tolerance of Clones of Eucalyptus grandis Exposed to Drift of the Herbicides Carfentrazone-Ethyl and Glyphosate. Planta Daninha 2019, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, N.; Freitas, F.; Furtado, I.; Teixeira, M.; Silva, V. Herbicide Mixtures to Control Dayflowers and Drift Effect on Coffee Cultures. Planta Daninha 2018, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassol, M.; Mattiuzzi, M.; Albrecht, A.J.P.; Albrecht, L.; Baccin, L.; Souza, C. Efficiency of Isolated and Associated Herbicides to Control Glyphosate-Resistant Sourgrass. Planta Daninha 2019, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Cruz, R.A.-D.; Domínguez-Martínez, P.A.; Da Silveira, H.M.; Cruz-Hipólito, H.E.; Palma-Bautista, C.; Vázquez-García, J.G.; Domínguez-Valenzuela, J.A.; De Prado, R. Management of Glyphosate-Resistant Weeds in Mexican Citrus Groves: Chemical Alternatives and Economic Viability. Plants 2019, 8, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, J.; Fernandes, T.C.C.; Marin-Morales, M.A. Induction of mitotic and chromosomal abnormalities on Allium cepa cells by pesticides imidacloprid and sulfentrazone and the mixture of them. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, N.; Shropshire, C.; Sikkema, P.H. Control of annual ryegrass with spring-applied herbicides prior to seeding corn. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2020, 100, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramires, A.C.; Constantin, J.; Junior, R.S.D.O.; Guerra, N.; Alonso, D.G.; Raimondi, M.A. Glyphosate associated with other herbicides for control of Commelina benghalensis and Spermacoce latifolia. Semin. Ciências Agrárias 2011, 32, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.H.; Duarte, J.C.B.; Mendes, K.F.; Sztoltz, J.; Ben, R.; Pereira, R.L. Eficácia de herbicidas aplicados em plantas adultas de Crotalaria spectabilis e Crotalaria ochroleuca. Rev. Bras. Herbic. 2012, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.M.D.O.; Constantin, J.; Júnior, R.S.D.O.; Guerra, N.; Braz, G.B.P.; Vilela, L.M.S.; Botelho, L.V.P.; Ávila, L.A. Sistemas de dessecação em áreas de trigo no inverno e atividade residual de herbicidas na soja. Rev. Bras. Herbic. 2013, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Marchi, S.R.; Bogorni, D.; Biazzi, L.; Bellé, J.R. Associações entre glifosato e herbicidas pós-emergentes para o controle de trapoeraba em soja RR®. Rev. Bras. Herbic. 2013, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Terra, G.M.; Miranda, G.R.; Ribeiro, H.J. Mistura De Tanque De Herbicidas Para O Controle De Grama-Seda Em Cafeeiro. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gustavo-Miranda-3/publication/330887307_MISTURA_DE_TANQUE_DE_HERBICIDAS_PARA_O_CONTROLE_DE_GRAMA-SEDA_EM_CAFEEIRO/links/5c59dcdfa6fdccb608a99c8d/MISTURA-DE-TANQUE-DE-HERBICIDAS-PARA-O-CONTROLE-DE-GRAMA-SEDA-EM-CAFEEIRO.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Maciel, C.D.G.; Da Silva, A.A.P.; Helvig, E.O.; De Oliveira Neto, A.M.; Guerra, N.; Sola Júnior, L.C.; Karam, D. Seletividade de misturas de herbicidas e inseticidas em tanque aplicadas em híbridos de milho. 2018. Available online: https://www.alice.cnptia.embrapa.br/handle/doc/1096584 (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Pereira, G.R.; Zobiole, L.H.S.; Rossi, C.V.S. Resposta no controle de capim-amargoso a mistura de tanque de glyphosate e haloxifope com auxinas sintéticas. Rev. Bras. Herbic. 2018, 17, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, H.; Martins, D.; Costa, S.; Marques, R.; De Souza, G.; De Campos, C. Eficiência de herbicidas no controle de plantas daninhas latifoliadas em mamona. Arq. Inst. Biológico 2012, 79, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, J.R.G.; Junior, A.C.S.; Rodrigues, A.C.P.; Martins, D. Eficiência da aplicação da mistura de glyphosate com saflufenacil sobre plantas de Brachiaria decumbens. Rev. Bras. Herbic. 2014, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dalazen, G.; Kruse, N.D.; Machado, S.L.D.O.; Balbinot, A. Sinergismo na combinação de glifosato e saflufenacil para o controle de buva. Pesqui. Agropecuária Trop. 2015, 45, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervoni, J.H.C.; Junior, W.R.C.; da Silva, A.F.; da Cruz, C. Eficácia de herbicidas isolados e em mistura para o controle de Amaranthus hybridus. Ciência Cult. 2016, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecki, C.; Carvalho, I.R.; Avila, L.A.; Agostinetto, D.; Vargas, L. Glyphosate and Saflufenacil: Elucidating Their Combined Action on the Control of Glyphosate-Resistant Conyza bonariensis. Agriculture 2020, 10, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.F.M.; Albrecht, A.J.P.; Damião, V.W.; Giraldeli, A.L.; de Marco, L.R.; Placido, H.F.; Albrecht, L.P. Selectivity of nicosulfuron isolated or in tank mixture to glyphosate and sulfonylurea tolerant soybean. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2018, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, A.A.M.; Albrecht, A.J.P.; Reis, F.C. Accase and glyphosate diferent formulations herbicides association interactions on sourgrass control. Planta Daninha 2014, 32, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, N.; Schmitt, J.; Corrêa, H.Z.; Visentin, R.P.; Jochem, W.; Costa, G.D.; Neto, A.M.D.O.; Noldin, J.A. Aryloxyphenoxypropionate in association with others herbicides in controlling weedy rice and barnyardgrass. Rev. Bras. De Ciências Agrárias 2020, 15, e7414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Zuo, L.; Li, W.; Guo, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, J. Greenhouse and field evaluation of isoxaflutole for weed control in maize in China. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, R.M.; Gomes, R.S.S.; Nunes, G.S.; Alves, T.G.; da Silva Souza, R.F.; Júnior, S.P.S. Tolerância do feijão-caupi a diferentes herbicidas aplicados em pós-emergência. Colloq. Agrar. 2018, 14, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesel, F.; Viecelli, M.; Trezzi, M.M.; Pagnoncelli, F.B., Jr. Interaction Between Saflufenacil and Other Oxidative Stress Promoting Herbicides to Control Wild Poinsettia. Planta Daninha 2018, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigatto, C.S.; Tarouco, C.P.; Nicoloso, F.T.; Berghetti, Á.L.P.; Leães, G.P.; Werle, I.S.; Ulguim, A.D.R. Barnyardgrass control using tank-mixed herbicides with saflufenacil and its influence in photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence. Ciência Rural 2020, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.M.; Duckworth, J.L.; Robertson, J. Toxicity of Bifenthrin and Mixtures of Bifenthrin Plus Acephate, Imidacloprid, Thiamethoxam, or Dicrotophos to Adults of Tarnished Plant Bug (Hemiptera: Miridae). J. Econ. Èntomol. 2018, 111, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nault, B.; Hsu, C.L.; Hoepting, C.A. Consequences of co-applying insecticides and fungicides for managing Thrips tabaci (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on onion. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012, 69, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, G.M.; Toscano, L.C.; Tomquelski, G.V.; Maruyama, W.I. Inseticidas no controle de Anticarsia gemmatalis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) e impacto sobre aranhas predadoras em soja. Rev. Bras. De Ciências Agrárias 2009, 4, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhu, Y.C.; Yao, J.; Adamczyk, J.; Luttrell, R. Synergistic toxicity and physiological impact of imidacloprid alone and binary mixtures with seven representative pesticides on honey bee (Apis mellifera). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanin, A.; da Silva, A.G.; Fernandes, C.P.C.; Ferreira, W.S.; Rattes, J.F. Tratamento de sementes de sorgo com inseticidas. Rev. Bras. Sement 2011, 33, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barros, E.M.; Rodrigues, A.R.D.S.; Batista, F.C.; Machado, A.V.D.A.; Torres, J. Susceptibility of boll weevil to ready-to-use insecticide mixtures. Arq. Inst. Biológico 2019, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, J.V.; Fiorin, R.A.; Stürmer, G.R.; Dal Prá, E.; Perini, C.R.; Bigolin, M. Application systems and insecticides to control Anticarsia gemmatalis in soybean. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agrícola E Ambient. 2012, 16, 910–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ghosal, A.; Chatterjee, M.; Bhattacharyya, A. Field Bio-efficacy of Some New Insecticides and Tank Mixtures against Whitefly on Cotton in New Alluvial Zone of West Bengal. Pestic. Res. J. 2018, 30, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.E.L.; Rolim, G.G.; De Maria, S.L.S.; Watanabe, S.Y.M.; Mendes, T.C.L. Efficacy and toxicity of insecticides to green peach aphid. Rev. Ciência Agrárias 2019, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.C.M.; Moreira, R.A.; Pinto, T.; Ogura, A.; Yoshii, M.P.C.; Lopes, L.F.P.; Montagner, C.C.; Goulart, B.V.; Daam, M.A.; Espíndola, E.L.G. Acute and chronic toxicity of 2,4-D and fipronil formulations (individually and in mixture) to the Neotropical cladoceran Ceriodaphnia silvestrii. Ecotoxicology 2020, 29, 1462–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohse, S.; Cortez, M.G.; Salomons, F.; Castro, F.C. Mistura de herbicidas com inseticidas e seus efeitos sobre híbridos de milho. Visão Acadêmica 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, G.S.; Johnson, W. Influence of Glyphosate or Glufosinate Combinations with Growth Regulator Herbicides and Other Agrochemicals in Controlling Glyphosate-Resistant Weeds. Weed Technol. 2012, 26, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.-Y.; Wu, H.-W.; Jiang, W.-L.; Ma, Y.-J.; Ma, Y. Weed and insect control affected by mixing insecticides with glyphosate in cotton. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 15, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Vechia, J.F.; Santos, R.T.; Griesang, F.; Santos, C.M.; Ferreira, M.C.; Andrade, D.J. Do combinations of insecticides and acaricides influence spray droplet formation and the interaction with citrus leaves? J. Plant Prot. Res. 2019, 59, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Vechia, J.F.; de Andrade, D.J.; de Azevedo, R.G.; Ferreira, M.D.C. Effects of insecticide and acaricide mixtures on Diaphorina citri control. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2019, 41, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echer, T.C. Influência da Mistura de Fungicidas e Inseticidas no Controle de Oídio (Microsphaera diffusa) da Soja em Casa de Vegetação. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zandonadi, C.H.S.; Da Cunha, J.P.A.R.; Alves, T.C.; Silva, S.M. Tank mixture of pesticides for Spodoptera frugiperda control in maize with triflumuron. Biosci. J. 2017, 33, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.J.; Lindsey, L.E.; Michel, A.P.; Dorrance, A.E. Effect of Mid-Season Foliar Fungicide and Foliar Insecticide Applied Alone and In-Combination on Soybean Yield. Crop. Soils 2018, 51, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willow, J.; Silva, A.; Veromann, E.; Smagghe, G. Acute effect of low-dose thiacloprid exposure synergised by tebuconazole in a parasitoid wasp. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Goes, A.; Garrido, R.; Reis, R.; Baldassari, R.; Soares, M. Evaluation of fungicide applications to sweet orange at different flowering stages for control of postbloom fruit drop caused by Colletotrichum acutatum. Crop. Prot. 2008, 27, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burpee, L.; Latin, R. Reassessment of Fungicide Synergism for Control of Dollar Spot. Plant Dis. 2008, 92, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.A.; Cowbrough, M.J.; Sikkema, P.H.; Tardif, F.J. Winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) tolerance to mixtures of herbicides and fungicides applied at different timings. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 93, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grichar, W.J.; Prostko, E.P. Effect of glyphosate and fungicide combinations on weed control in soybeans. Crop. Prot. 2009, 28, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W. Improved SWOT Approach for Conducting Strategic Planning in the Construction Industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).