Forest Surface Changes and Cultural Values: The Forests of Tuscany (Italy) in the Last Century

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Forests and shrubland vegetation in evolution;

- Sclerophyll vegetation;

- Broadleaved forests;

- Coniferous forests;

- Mixed forests of broadleaved and conifers.

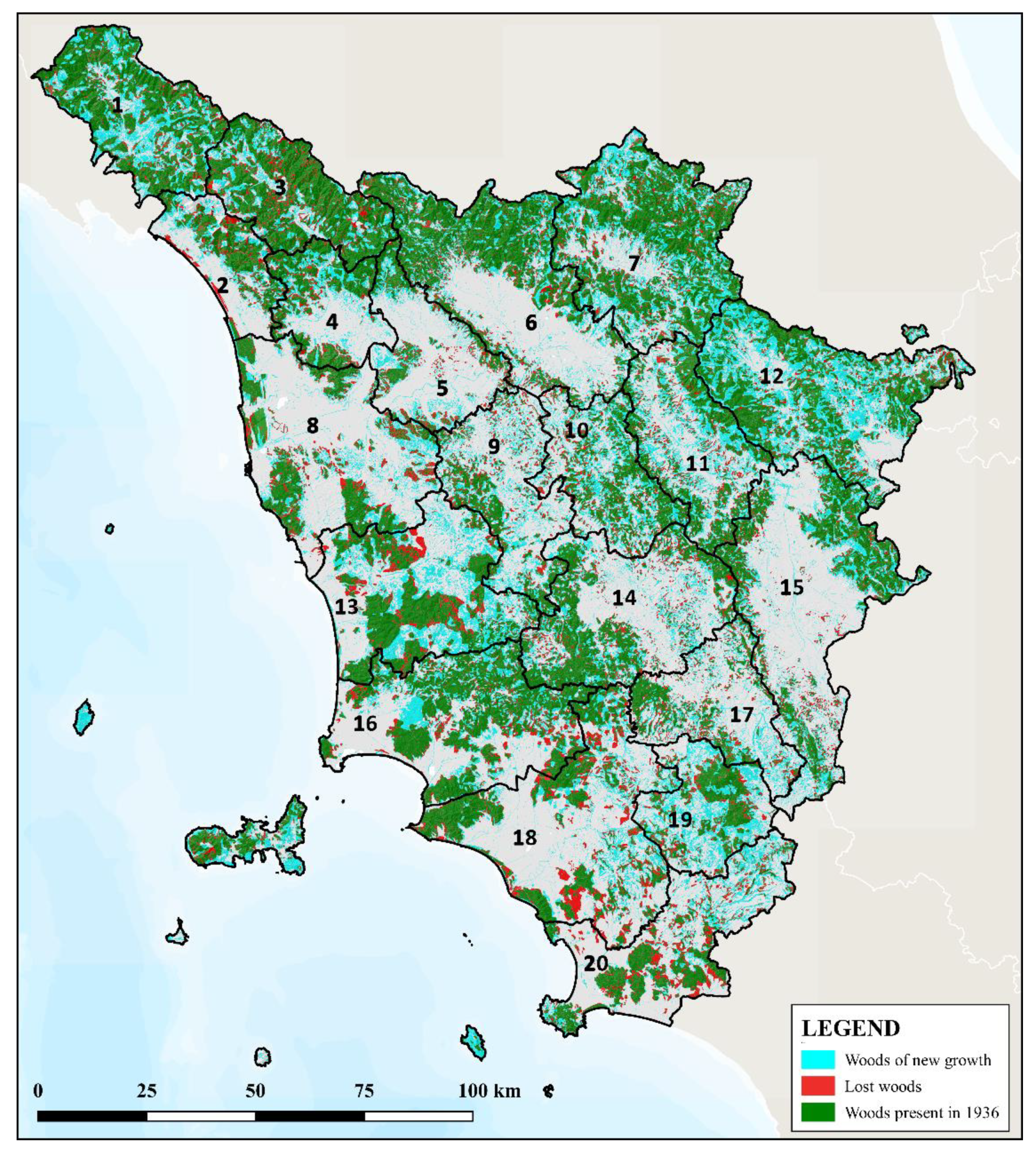

- Woods present in 1936: all the forest surfaces of 2016 that were already covered by woods in 1936.

- Woods of new growth: all the forest surfaces of 2016 that in 1936 were designed for other uses, such as agriculture and pastures, and therefore, this corresponds the surfaces in which the forests expanded in the period 1936–2016.

- Lost woods: all the non-forest areas of 2016 that in 1936 were instead covered by forests, corresponding to the areas from which forests have been removed.

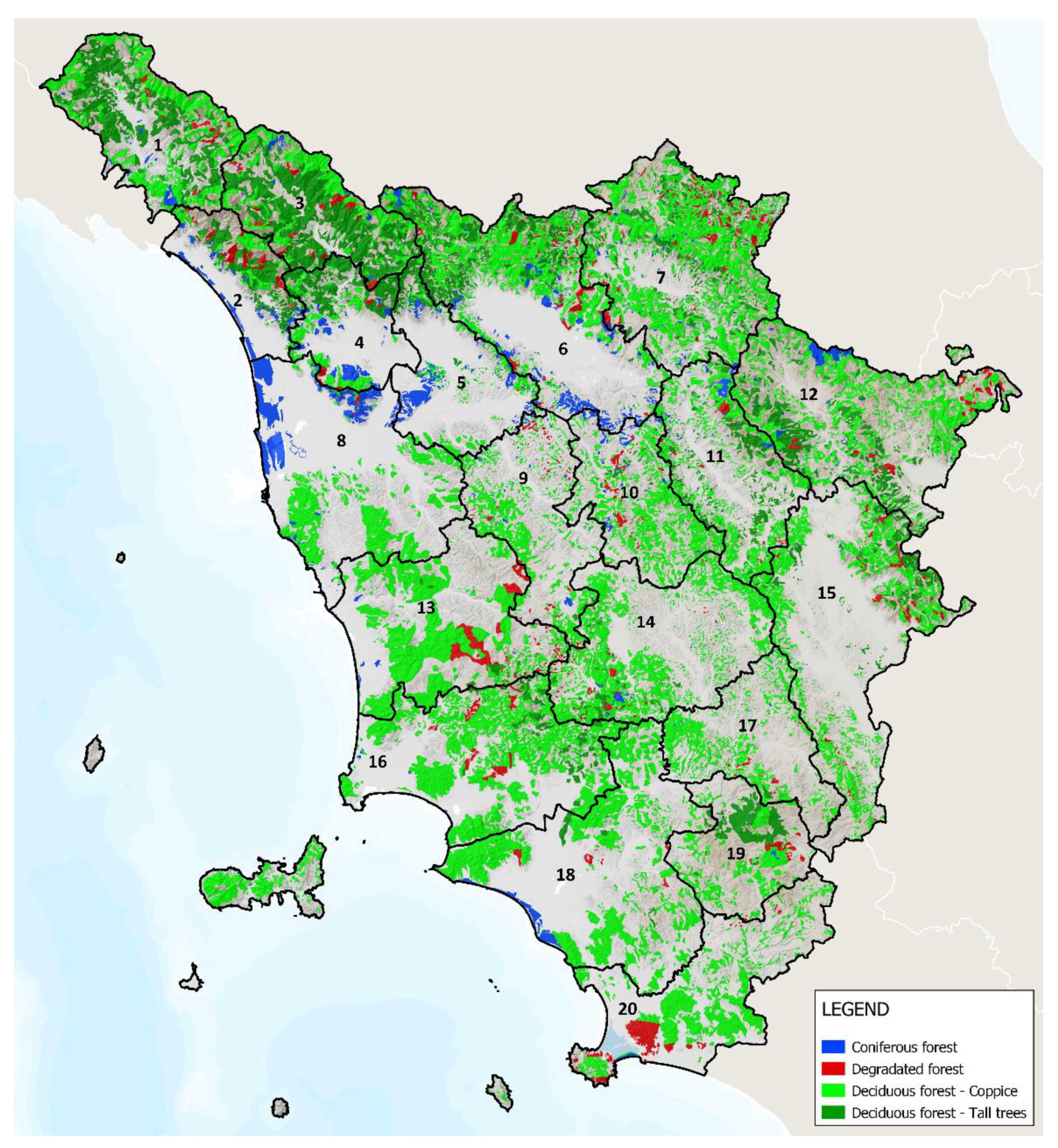

3. Results

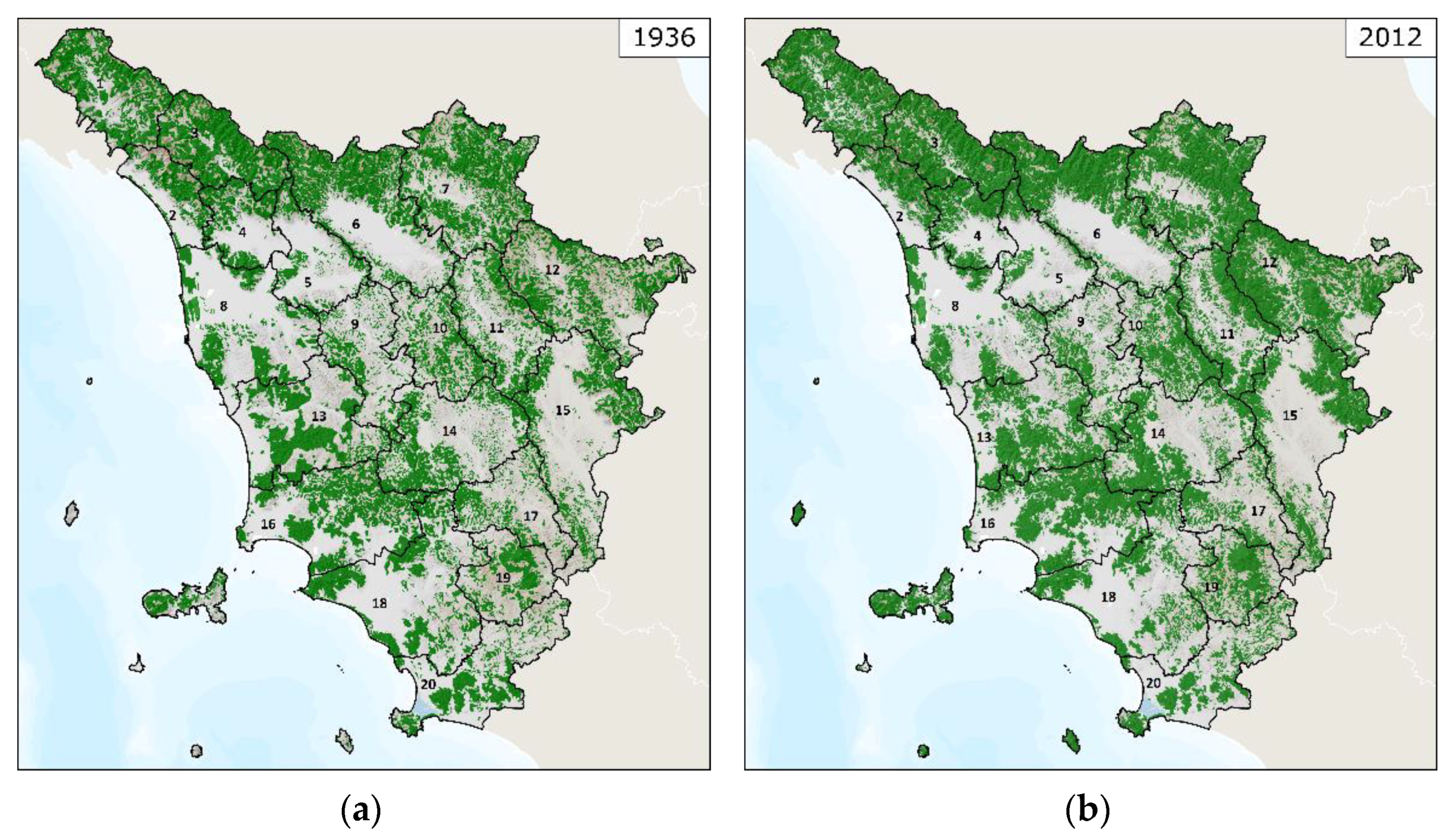

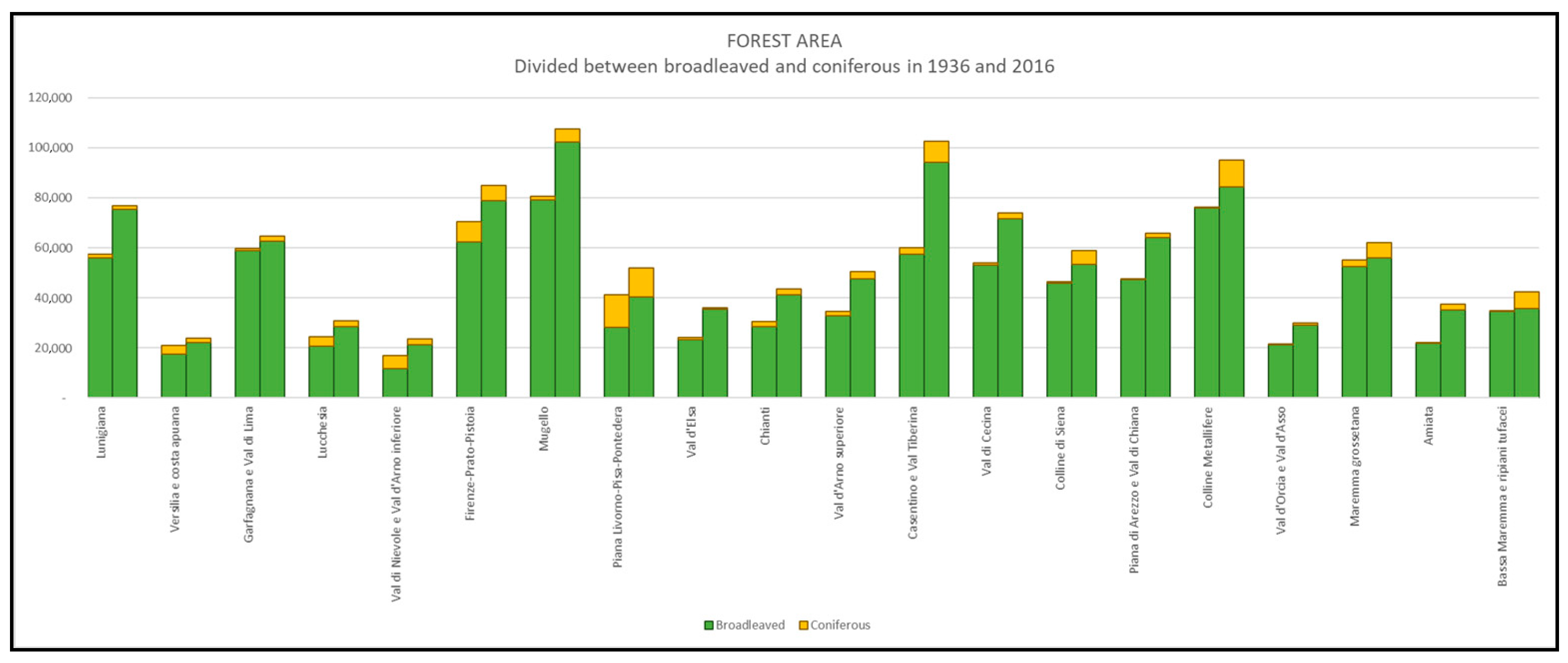

3.1. The Forests in Tuscany in 1936

3.2. The Comparison with the Forests in 2016

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parrotta, J.A.; Agnoletti, M. Traditional forest knowledge: Challenges and opportunities. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 249, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MCPFE. Vienna Resolution 3. In Proceedings of the Expert Level Meeting of the Ministerial Conference for the Protection of Forests in Europe, Warsaw, Poland, 14–15 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Agnoletti, M.; Anderson, A.; Johann, E.; Kulvik, M.; Kushlin, A.; Mayer, P.; Montiel Molina, C.; Parrotta, J.; Rotherham, I.D.; Saratsi, E. The Introduction of Historical and Cultural values in the Sustainable Management of European Forests. Glob. Environ. 2008, 2, 171–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Forum on Forests (UNFF). Report of the Secretary-General: Traditional Forest-Related Knowledge (E/CN.18/2004/7); United Nations Forum on Forests (UNFF): New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, L.D.; Gevaña, D.T.; Carandang, A.P.; Camacho, S.C. Indigenous knowledge and practices for the sustainable management of Ifugao forests in Cordillera, Philippines. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2016, 12, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzi, G.; Gambini, S.; Buldrini, F.; Ferretti, F.; Muzzi, E.; Maresi, G.; Nascimbene, J. Contrasting patterns of tree features, lichen, and plant diversity in managed and abandoned old-growth chestnut orchards of the northern Apennines (Italy). For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 470, 118207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, F.; Valerino, L. Changements du paysage et biodiversité dans les châtaigneraies cévenoles (sud de la France). Ecol. Mediterr. 1997, 23, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Santoro, A. Cultural values and sustainable forest management: The case of Europe. J. For. Res. 2015, 20, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.N. Ethnoforestry: Local Knowledge for Sustainable Forestry and Livelihood Security; Himanshu Publications: Udaipur, India, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Maffi, L. Biocultural Diversity and Sustainability. In The SAGE handbook of Environmental and Society; SAGE publications: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO; sCBD. UNESCO–CBD Joint Program between Biological and Cultural Diversity; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO; sCBD. Florence Declaration on the Links between Biological and Cultural Diversity; UNESCO: Florence, Italy, 2014; Available online: https://www.landscapeunifi.it/land/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/UNESCO-CBD_JP_Florence_Declaration.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Agnoletti, M.; Rotherham, I.D. Landscape and Biocultural Diversity. Biodivers. Conserv. 2015, 24, 3155–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohafkan, P.; Altieri, M.A. Globally Important agricultural heritage systems. In A Legacy for the Future; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, A.; Venturi, M.; Bertani, R.; Agnoletti, M. A review of the role of forests and agroforestry systems in the FAO Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) programme. Forests 2020, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, M.; Stereńczak, K. What do we expect from forests? The European view of public demands. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 209, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Romero, M.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; González, J.A.; Martín-López, B. Exploring the knowledge landscape of ecosystem services assessments in Mediterranean agroecosystems: Insights for future research. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 37, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzarri, M.; Tognetti, R.; Marchetti, M. Forest ecosystem services: Issues and challenges for biodiversity, conservation, and management in Italy. Forests 2015, 6, 1810–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomou, A.D.; Karetsos, G.; Skoufogianni, E.; Martinos, K.; Sfougaris, A.; Tsagari, K. Assessment of Greek forests protection and management. In Sustainable Development in Mountain Regions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, Z.; Verburg, P. Mediterranean land systems: Representing diversity and intensity of complex land systems in a dynamic regions. Landsc Urban. Plan. 2017, 165, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, I.R. Forests and hydrological services: Reconciling public and science perceptions. Land Use Water Resour. Res. 2002, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuuluvainen, T. Forest management and biodiversity conservation based on natural ecosystem dynamics in northern Europe: The complexity challenge. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2009, 38, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gołos, P. Social importance of public forest functions-desirable for recreation model of tree stand and forest. For. Res. Pap. 2010, 71, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eriksson, L.; Nordlund, A.M.; Olsson, O.; Westin, K. Recreation in different forest settings: A scene preference study. Forests 2012, 3, 923–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, V.S.; Frivold, L.H. Public preferences for forest structures: A review of quantitative surveys from Finland, Norway and Sweden. Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2008, 7, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Robles-Gil, P.; Hoffmann, M.; Pilgrim, J.; Brooks, T.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Lamoreux, J.; Da Fonseca, G.A.B. Hotspots Revisited: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions; CEMEX: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Bravo, S.; Valcárcel, V.; Vargas, P.; Luceño, M. Geographical speciation related to Pleistocene range shifts in the western Mediterranean mountains (Reseda sect. Glaucoreseda, Resedaceae). Taxon 2010, 59, 466–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karetsos, G.; Solomou, A.D.; Trigas, P.; Tsagari, K. The vascular flora of Mt. Oiti National Park and the surrounding area in Greece. J. For. Sci. 2018, 64, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plexida, S.; Solomou, A.; Poirazidis, K.; Sfougaris, A. Factors affecting biodiversity in agrosylvopastoral ecosystems with in the Mediterranean Basin: A systematic review. J. Arid Environ. 2018, 151, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Médail, F.; Monnet, A.C.; Pavon, D.; Nikolic, T.; Dimopoulos, P.; Bacchetta, G.; Arroyo, J.; Barina, Z.; Albassatneh, M.C.; Domina, G.; et al. What is a tree in the Mediterranean Basin hotspot? A critical analysis. For. Ecosyst. 2019, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proutsos, N.; Solomou, A.; Karetsos, G.; Tsagari, K.; Mantakas, G.; Kaoukis, K.; Bourletsikas, A.; Lyrintzis, G. The Ecological Status of Juniperus foetidissima Forest Stands in the Mt. Oiti-Natura 2000 Site in Greece. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, G.; Crisarà, R.; Cannavò, S.; Musarella, C.M. Phytotoponims of southern Calabria: A tool for the analysis of the landscape and its transformations. Atti Soc. Toscana Sci. Nat. Mem. Ser. B 2017, 124, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasta, S.; Sala, G.; La Mantia, T.; Bondì, C.; Tinner, W. The past distribution of Abies nebrodensis (Lojac.) Mattei: Results of a multidisciplinary study. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2020, 29, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-K.; Nakagoshi, N.; Fu, B.J.; Morimoto, Y. (Eds.) Landscape Ecological Applications in Man-Influenced Areas: Linking Man and Nature Systems. In Landscape Ecological Applications in Man-Influenced Areas; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, A.P. Forest landscapes as social-ecological systems and implications for management. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2018, 177, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östlund, L.; Zackrisson, O.; Hörnberg, G. Trees on the border between nature and culture: Culturally modified trees in boreal Sweden. Environ. Hist. 2002, 7, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johann, E.; Agnoletti, M.; Axelsson, A.L.; Bürgi, M.; Östlund, L.; Rochel, X.; Winiwater, V. History of secondary Norway spruce forests in Europe. In European Forest Institute Research Report; Spiecker, H., Hansen, J., Klimo, E., Skovsgaard, J.P., Sterba, H., von Teufel, K., Eds.; Norway Spruce Conversion—Options and Consequences; Brill: Leiden, Netherlands, 2004; pp. 25–62. [Google Scholar]

- IRPET. Rapporto Sullo Stato Delle Foreste in Toscana 2019; IRPET—Istituto Regionale Programmazione Economica Toscana & Compagnia Delle Foreste: Firenze, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Regione Toscana. Quadro Strategico Regionale per uno Sviluppo Sostenibile ed Equo. Ciclo di Programmazione Comunitaria 2021–2027; Regione Toscana: Firenze, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Agnoletti, M.; Santoro, A. Rural landscape planning and forest management in Tuscany (Italy). Forests 2018, 9, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereni, E. Storia del Paesaggio Agrario Italiano; Laterza: Bari, Italy, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Flan, P.; Garci, J.M.; Ortigosa, L. Geomorphological evolution of abandoned fields. A case study in the Central Pyrenees. Catena 1992, 19, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanchi, S.; Freppaz, M.; Agnelli, A.; Reinsch, T.; Zanini, E. Properties, best management practices and conservation of terraced soils in Southern Europe (from Mediterranean areas to the Alps): A review. Quat. Int. 2012, 265, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoate, C.; Báldi, A.; Beja, P.; Boatman, N.D.; Herzon, I.; Van Doorn, A.; de Snoo, G.R.; Rakosy, L.; Ramwell, C. Ecological impacts of early 21st century agricultural change in Europe: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 22–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johann, E. Traditional forest management under the influence of science and industry: The story of the alpine cultural landscapes. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 249, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.Lgs. n. 42/2002—Code of the Cultural and Landscape Heritage, Pursuant to Article 10 of Law no. 137 of 6 July 2002; GU Serie Generale n.45-Suppl. Ordinario n. 28: Roma, Italy. 2002. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/cld/en/legislation/ita/legislative_decree_no._42_of_22_january_2004-_code_of_the_cultural_and_landscape_heritage/title_i/articles_1_2_3/code_of_the_cultural_and_landscape_heritage.html? (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- MAIC. Statistica Forestale del Regno d’Italia; MAIC: Firenze, Italy, 1870. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzini, C.M. La Toscana Agricola; Tipografia del Senato: Rome, Italy, 1881. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbrielli, A. Le Trasformazioni del Paesaggio Forestale in Toscana: Un Tentativo di Sintesi Storica; Accademia Italiana di Scienze Forestali: Firenze, Italy, 1997; Volume Quarantaseiesimo. [Google Scholar]

- Puddu, G. Le trasformazioni del paesaggio viste attraverso la cartografia storica: Il caso della regione Sardegna; Università degli studi della Tuscia: Viterbo, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Giunta Regionale Toscana. Piano di Indirizzo Territoriale con valenza di Piano Paesaggistico; Giunta Regionale Toscana: Toscana, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- AA.VV. La Toscana dei boschi; Edizioni Vallombrosa; Regione Toscana Giunta Regionale: Florence, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rotherham, I.D. The call of the wild: Perceptions, history people & ecology in the emerging paradigms of wilding. ECOS 2014, 35, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Regione Toscana. Rapporto sullo stato delle politiche del paesaggio; Regione Toscana: Florence, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- EuroCoppice Working Group 5. Socio-Economic Factors Influencing Coppice Management in Europe; COST Action FP1301 Reports; Albert Ludwig University: Freiburg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.; Unrau, A. Coppice forests in Europe. A Traditional Landuse with New Perspectives. In Coppice Forests in Europe; Unrau, A., Becker, G., Spinelli, R., Lazdina, D., Magagnotti, N., Nicolescu, V.N., Buckley, P., Bartlett, D., Kofman, P.D., Eds.; Albert Ludwig University: Freiburg, Germany, 2018; pp. 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, L.; Maltoni, A.; Mariotti, B.; Paci, M. La Selvicoltura dei Castagneti da frutto Abbandonati della Toscana; Arsia Regione Toscana: Sesto Fiorentino, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tieskens, K.F.; Schulp, C.J.; Levers, C.; Lieskovský, J.; Kuemmerle, T.; Plieninger, T.; Verburg, P.H. Characterizing European cultural landscapes: Accounting for structure, management intensity and value of agricultural and forest landscapes. Land Use Policy 2017, 62, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.M.; Leadley, P.W.; Proença, V.; Alkemade, R.; Scharlemann, J.P.; Fernandez-Manjarrés, J.F.; Araújo, M.B.; Balvanera, P.; Biggs, R.; Cheung, W.W.L.; et al. Scenarios for global biodiversity in the 21st century. Science 2010, 330, 1496–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepsen, M.R.; Kuemmerle, T.; Müller, D.; Erb, K.; Verburg, P.H.; Haberl, H.; Vesterager, J.P.; Andrič, M.; Antrop, M.; Austrheim, G.; et al. Transitions in European land-management regimes between 1800 and 2010. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M. The degradation of traditional landscape in a mountain area of Tuscany during the 19th and 20th centuries: Implications for biodiversity and sustainable management. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 249, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandolini, P.; Cevasco, A.; Capolongo, D.; Pepe, G.; Lovergine, F.; Del Monte, M. Response of terraced slopes to a very intense rainfall event and relationships with land abandonment: A case study from Cinque Terre (Italy). Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciabatti, G.; Gabellini, A.; Ottaviani, C.; Perugi, A. I rimboschimenti in Toscana e la loro Gestione; Arsia Regione Toscana: Sesto Fiorentino, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| 1936 Forest Map | Reclassification |

|---|---|

| Beech forests | Broadleaved forests |

| Chestnut forests | Broadleaved forests |

| Conifers | Coniferous forests |

| Degraded forests | Degraded forests |

| Forests with other species or mixed forests | Broadleaved forests |

| Oak forests | Broadleaved forests |

| Landscape Unit | High Forest | Coppice | Total Broadleaved | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ha) | (%) | (ha) | (%) | (ha) | ||

| 1 | Lunigiana | 29,899 | 53% | 26,144 | 47% | 56,042 |

| 2 | Versilia e costa apuana | 12,442 | 71% | 5007 | 29% | 17,449 |

| 3 | Garfagnana e Val di Lima | 40,723 | 69% | 18,112 | 31% | 58,835 |

| 4 | Lucchesia | 12,360 | 60% | 8289 | 40% | 20,649 |

| 5 | Val di Nievole e Val d’Arno inferiore | 4136 | 36% | 7417 | 64% | 11,553 |

| 6 | Firenze-Prato-Pistoia | 22,378 | 36% | 40,003 | 64% | 62,381 |

| 7 | Mugello | 17,687 | 22% | 61,322 | 78% | 79,009 |

| 8 | Piana Livorno-Pisa-Pontedera | 388 | 1% | 27,684 | 99% | 28,072 |

| 9 | Val d’Elsa | 1972 | 9% | 21,107 | 91% | 23,079 |

| 10 | Chianti | 2599 | 9% | 25,756 | 91% | 28,355 |

| 11 | Val d’Arno superiore | 10,066 | 31% | 22,773 | 69% | 32,839 |

| 12 | Casentino e Val Tiberina | 18,978 | 33% | 38,438 | 67% | 57,416 |

| 13 | Val di Cecina | 6649 | 13% | 46,439 | 87% | 53,088 |

| 14 | Colline di Siena | 4156 | 9% | 41,633 | 91% | 45,789 |

| 15 | Piana di Arezzo e Val di Chiana | 10,751 | 23% | 36,620 | 77% | 47,371 |

| 16 | Colline Metallifere | 8397 | 11% | 67,549 | 89% | 75,946 |

| 17 | Val d’Orcia e Val d’Asso | 892 | 4% | 20,221 | 96% | 21,113 |

| 18 | Maremma grossetana | 2582 | 5% | 49,993 | 95% | 52,575 |

| 19 | Amiata | 9016 | 42% | 12,601 | 58% | 21,617 |

| 20 | Bassa Maremma e ripiani tufacei | 5659 | 16% | 28,802 | 84% | 34,461 |

| TUSCANY | 221,730 | 27% | 605,911 | 73% | 827,640 | |

| Forest Surface 1936 | Forest Surface 2016 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape Unit | Totatal Surface (ha) | (ha) | (%) | (ha) | (%) | |

| 1 | Lunigiana | 97,451 | 57,284 | 59% | 76,687 | 79% |

| 2 | Versilia e costa apuana | 53,938 | 20,920 | 39% | 23,797 | 44% |

| 3 | Garfagnana e Val di Lima | 83,400 | 59,742 | 72% | 64,753 | 78% |

| 4 | Lucchesia | 58,366 | 24,228 | 42% | 30,651 | 53% |

| 5 | Val di Nievole e Val d’Arno inferiore | 78,305 | 16,838 | 22% | 23,415 | 30% |

| 6 | Firenze-Prato-Pistoia | 160,843 | 70,266 | 44% | 84,949 | 53% |

| 7 | Mugello | 150,731 | 80,493 | 53% | 107,469 | 71% |

| 8 | Piana Livorno-Pisa-Pontedera | 157,841 | 41,034 | 26% | 51,849 | 33% |

| 9 | Val d’Elsa | 90,561 | 23,991 | 26% | 36,014 | 40% |

| 10 | Chianti | 77,024 | 30,395 | 39% | 43,337 | 56% |

| 11 | Val d’Arno superiore | 92,368 | 34,411 | 37% | 50,531 | 55% |

| 12 | Casentino e Val Tiberina | 150,032 | 60,081 | 40% | 102,603 | 68% |

| 13 | Val di Cecina | 136,987 | 53,898 | 39% | 73,980 | 54% |

| 14 | Colline di Siena | 131,426 | 46,374 | 35% | 58,889 | 45% |

| 15 | Piana di Arezzo e Val di Chiana | 176,625 | 47,558 | 27% | 65,740 | 37% |

| 16 | Colline Metallifere | 169,846 | 76,264 | 45% | 95,001 | 56% |

| 17 | Val d’Orcia e Val d’Asso | 79,967 | 21,263 | 27% | 29,907 | 37% |

| 18 | Maremma grossetana | 172,533 | 54,929 | 32% | 61,896 | 36% |

| 19 | Amiata | 67,422 | 21,801 | 32% | 37,454 | 56% |

| 20 | Bassa Maremma e ripiani tufacei | 114,933 | 34,746 | 30% | 42,461 | 37% |

| TUSCANY | 2,300,599 | 876,518 | 38% | 1,161,383 | 50% | |

| Landscape Unit | Areas that Were Forests in 1936 and that Still Are Forests (ha) | Areas that Became Forests after 1936 (ha) | Deforested Areas (ha) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lunigiana | 51,119 | 25,568 | 6165 |

| 2 | Versilia e costa apuana | 15,786 | 8011 | 5134 |

| 3 | Garfagnana e Val di Lima | 51,770 | 12,983 | 7972 |

| 4 | Lucchesia | 20,802 | 9849 | 3427 |

| 5 | Val di Nievole e Val d’Arno inferiore | 12,313 | 11,102 | 4525 |

| 6 | Firenze-Prato-Pistoia | 61,104 | 23,845 | 9163 |

| 7 | Mugello | 69,906 | 37,562 | 10,587 |

| 8 | Piana Livorno-Pisa-Pontedera | 31,738 | 20,112 | 9297 |

| 9 | Val d’Elsa | 17,028 | 18,986 | 6963 |

| 10 | Chianti | 23,819 | 19,518 | 6575 |

| 11 | Val d’Arno superiore | 27,615 | 22,916 | 6796 |

| 12 | Casentino e Val Tiberina | 51,997 | 50,606 | 8084 |

| 13 | Val di Cecina | 43,384 | 30,596 | 10,514 |

| 14 | Colline di Siena | 37,034 | 21,856 | 9340 |

| 15 | Piana di Arezzo e Val di Chiana | 38,426 | 27,314 | 9131 |

| 16 | Colline Metallifere | 64,480 | 30,520 | 11,783 |

| 17 | Val d’Orcia e Val d’Asso | 15,023 | 14,883 | 6240 |

| 18 | Maremma grossetana | 38,627 | 23,269 | 16,302 |

| 19 | Amiata | 17,134 | 20,320 | 4667 |

| 20 | Bassa Maremma e ripiani tufacei | 23,577 | 18,884 | 11,169 |

| TUSCANY | 712,682 | 448,701 | 163,836 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piras, F.; Venturi, M.; Corrieri, F.; Santoro, A.; Agnoletti, M. Forest Surface Changes and Cultural Values: The Forests of Tuscany (Italy) in the Last Century. Forests 2021, 12, 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12050531

Piras F, Venturi M, Corrieri F, Santoro A, Agnoletti M. Forest Surface Changes and Cultural Values: The Forests of Tuscany (Italy) in the Last Century. Forests. 2021; 12(5):531. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12050531

Chicago/Turabian StylePiras, Francesco, Martina Venturi, Federica Corrieri, Antonio Santoro, and Mauro Agnoletti. 2021. "Forest Surface Changes and Cultural Values: The Forests of Tuscany (Italy) in the Last Century" Forests 12, no. 5: 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12050531

APA StylePiras, F., Venturi, M., Corrieri, F., Santoro, A., & Agnoletti, M. (2021). Forest Surface Changes and Cultural Values: The Forests of Tuscany (Italy) in the Last Century. Forests, 12(5), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12050531