Fragmentation and Coordination of REDD+ Finance under the Paris Agreement Regime

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Backgrounds

2.1. Transition of the Climate Regime and Characteristics of REDD+ Finance

2.2. Donors’ Motivations for REDD+ Finance

2.3. Fragmentation of REDD+ Finance

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Fragmentation of REDD+ Finance

3.2.2. Classification of REDD+ Countries by REDD+ Progress

4. Results

4.1. Overview of REDD+ Finance

4.2. Fragmentation of REDD+ Finance

4.2.1. Fragmentation in Recipient Countries Grouped by Major Forest Type

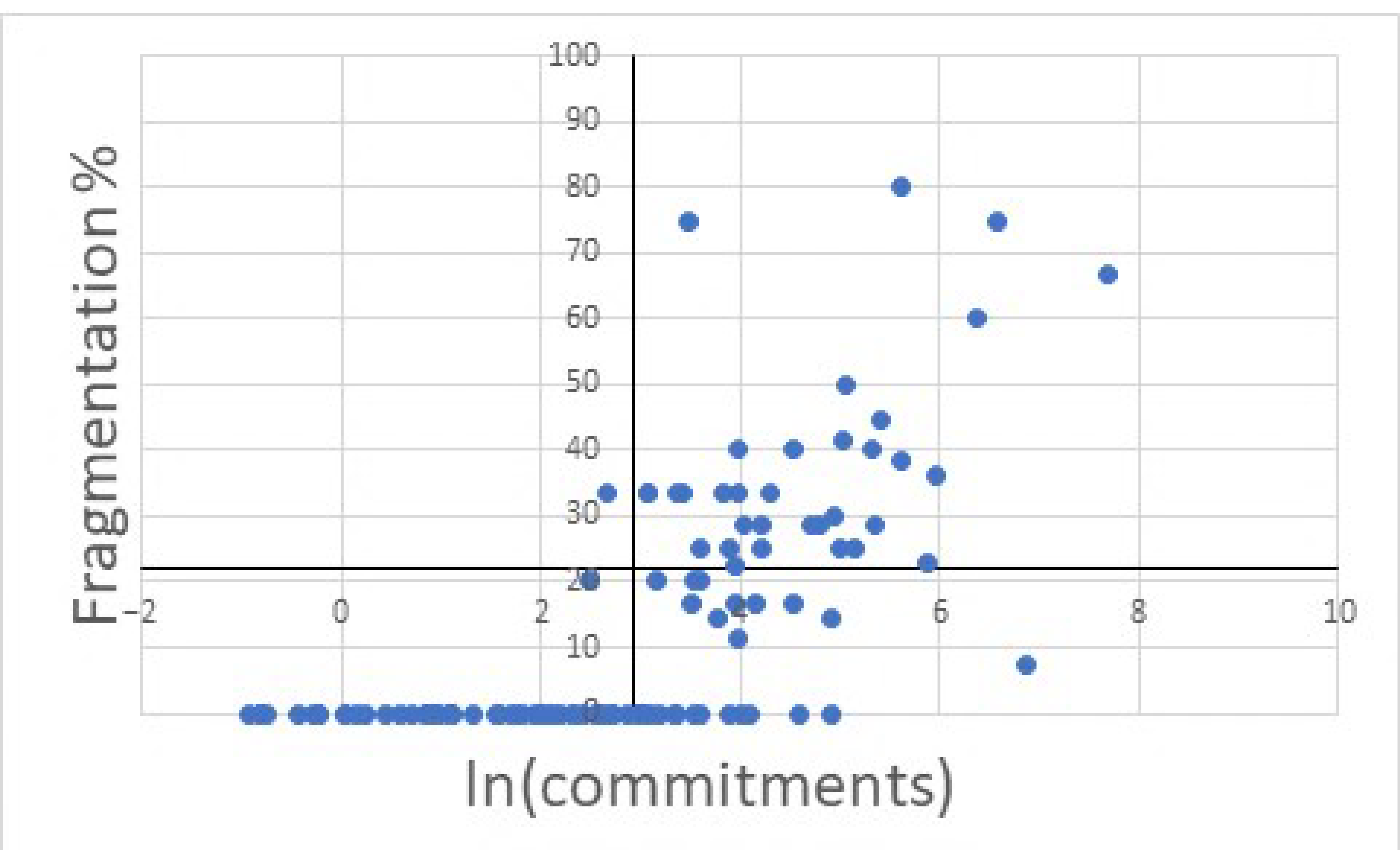

4.2.2. Fragmentation among Recipients Reflecting Number of Donors and Size of Received REDD+ Finance

4.2.3. Fragmentation of Bilateral and Multilateral REDD+ Finance

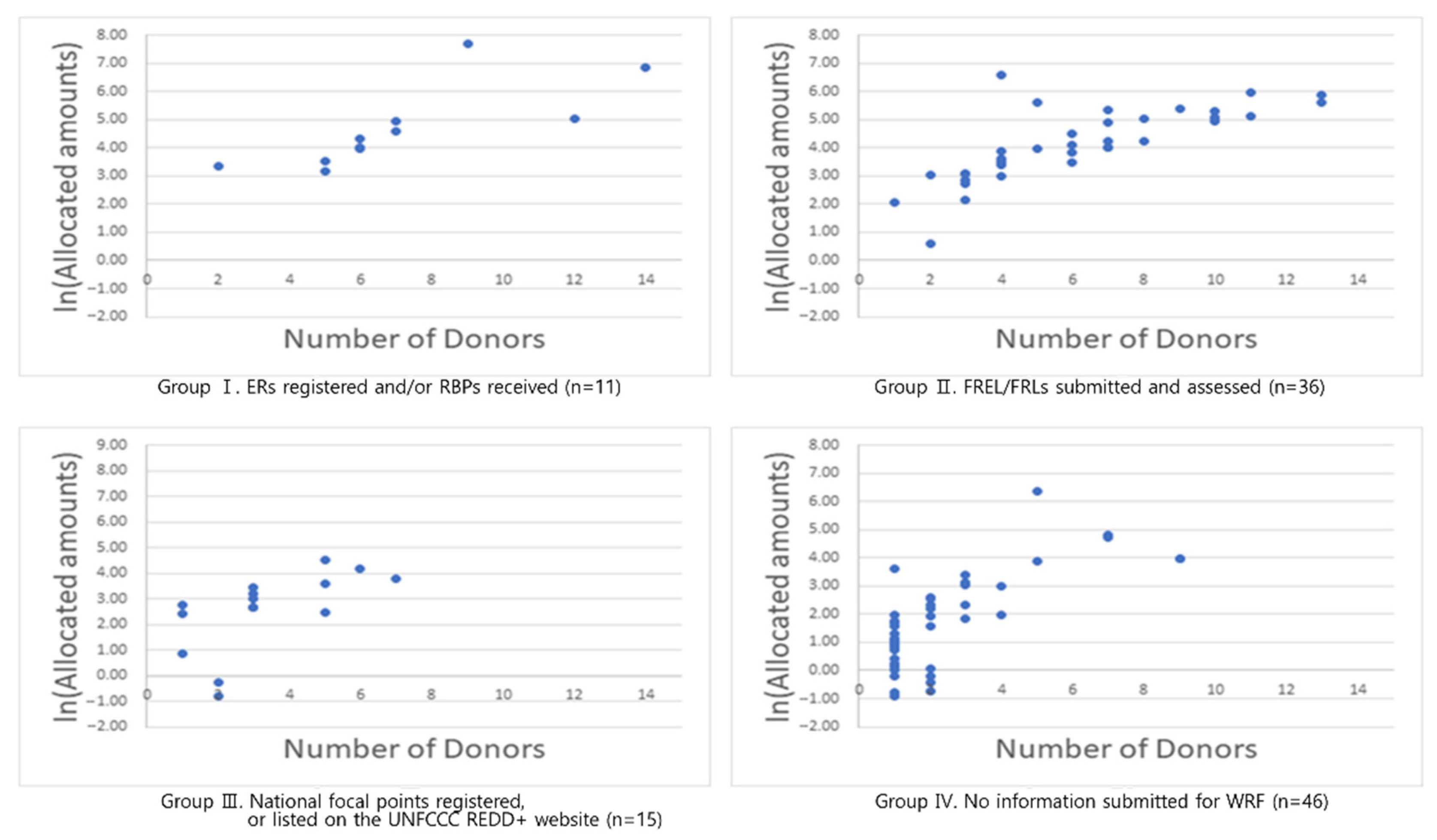

4.3. Classification of REDD+ Countries by REDD+ Progress

5. Discussion

5.1. The Fragmentation of REDD+ Finance

5.2. Adjustments under the Paris Climate Regime

5.3. Contributions and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ER(s) | Emission Reduction Result(s) |

| FAO VRD | Food and Agricultural Organizations Voluntary REDD+ Database |

| FREL(s)/FRL(s) | Forest Reference Emission Level(s)/Forest Reference Level(s) |

| GCF | Green Climate Fund |

| ITMO(s) | Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcome(s) |

| MRV | Measuring, Reporting, and Verification |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contribution |

| NFMS | National Forest Monitoring System |

| NSAP | National Strategy and Action Plan |

| ODI CFU | Overseas Development Institute Climate Funds Update |

| RBP(s) | Results-based payment(s) |

| REDD+ | Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, as well as fostering conservation, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks |

| SIS | Summary of Information on Safeguards |

| WRF | UNFCCC Warsaw Framework on REDD+ |

References

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Decision 9/CP.19: Work Programme on Results-based Finance to Progress the Full Implementation of the Activities Referred to in Decision 1/CP.16, paragraph 70. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Parties on Its Nineteenth Session, Warsaw, Poland, 11–22 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pasgaard, M.; Sun, Z.; Müller, D.; Mertz, O. Challenges and opportunities for REDD+: A reality check from perspectives of effectiveness, efficiency and equity. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 63, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The Cancun Agreements: Outcome of the Work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperation under the Convention, Decision 1/CP.16, FCC/CP/2010/7 Add.1. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Parties on Its Sixteenth Session, Cancun, Mexico, 29 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Decision 14/CP.19: Modalities for measuring, reporting, and verifying. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Parties on Its Nineteenth Session, Warsaw, Poland, 11–23 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, N.; Glennie, J. Going beyond aid effectiveness to guide the delivery of climate finance. ODI Backgr. Notes 2011. Available online: https://odi.org/en/publications/going-beyond-aid-effectiveness-to-guide-the-delivery-of-climate-finance/ (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Norman, M.; Nakhooda, S. The State of REDD+ Finance. SSRN Electron. J. 2015. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2622743 (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Pickering, J.; Jotzo, F.; Wood, P.J. Sharing the Global Climate Finance Effort Fairly with Limited Coordination. Glob. Environ. Politics 2015, 15, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Viña, A.G.M.; de Leon, A.; Barrer, R.R. History and future of REDD+ in the UNFCCC: Issues and challenges. Res. Handb. REDD-Plus Int. Law 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Decision 1/CP. 17: Establishment of an Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Parties on Its Seventeenth Session, Durban, South Africa, 28 November–11 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fallasch, F.; De Marez, L. New and Additional? An Assessment of Fast-Start Finance Commitments of the Copenhagen Accord; Climate Analytics: Postdam, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Well, M.; Carrapatoso, A. REDD+ finance: Policy making in the context of fragmented institutions. Clim. Policy 2017, 17, 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhooda, S.; Watson, C.; Schalatek, L. The Global Climate Finance Architecture. Overseas Dev. Inst. 2015. Available online: https://odi.org/en/publications/climate-finance-fundamentals-2-the-evolving-global-climate-finance-architecture/ (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Gupta, A.; Pistorius, T.; Vijge, M.J. Managing fragmentation in global environmental governance: The REDD+ Partnership as bridge organization. Int. Environ. Agreements Polit. Law Econ. 2016, 16, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simula Ardo, M. Analysis of REDD+ Financing Gaps and Overlaps. REDD+ Partnership 1–99. 2010. Available online: https://www.fao.org/partnerships/redd-plus-partnership/25159-09eb378a8444ec149e8ab32e2f5671b11.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Davis, C.; Daviet, F. Investing in Results: Enhancing Coordination for More Effective Interim REDD+ Financing Executive Summary; WRI Working Paper; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Available online: http://wri.org (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Streck, C. Financing REDD+: Matching needs and ends. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, J.; Betzold, C.; Skovgaard, J. Special issue: Managing fragmentation and complexity in the emerging system of international climate finance. Int. Environ. Agreem. 2017, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Twenty-First Session, Paris, France, 30 November–13 December 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Kim, D.; Kim, D.; Lee, D.-H.; Park, S.; Kim, S. Centralization of the Global REDD+ Financial Network and Implications under the New Climate Regime. Forests 2019, 10, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Decision 2/CP.13: Reducing emissions from deforestation in developing countries: Approaches to stimulate action. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Parties on Its Thirteenth Session, Bali, Indonesia, 3 December–15 December 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Adoption of the Paris Agreement; Paris, France, 2015; Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; Kyoto, Japan, 1998; Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpeng.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- McKinley, R.D.; Little, R. The US aid relationship: A test of the recipient need and the donor interest models. Polit. Stud. 1979, 27, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maizels, A.; Nissanke, M.K. Motivations for aid to developing countries. World Dev. 1984, 12, 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnside, C.; Dollar, D. Aid, policies, and growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 847–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berthélemy, J. Bilateral donors’ interest vs. recipients’ development motives in aid allocation: Do all donors behave the same? Rev. Dev. Econ. 2006, 10, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davies, R.B.; Klasen, S. Darlings and orphans: Interactions across donors in international aid. Scand. J. Econ. 2019, 121, 243–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Dollar, D. Who gives foreign aid to whom and why? J. Econ. Growth 2000, 5, 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthélemy, J.-C.; Tichit, A. Bilateral donors’ aid allocation decisions—A three-dimensional panel analysis. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2004, 13, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lahiri, S.; Raimondos-Møller, P. Lobbying by ethnic groups and aid allocation. Econ. J. 2000, 110, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.-H. Determinants of Bilateral REDD+ Cooperation Recipients in Kyoto Protocol Regime and Their Implications in Paris Agreement Regime. Forests 2020, 11, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher, E. How fragmented is aid? OECD DAC J. Dev. 2009, 10, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E. Aid fragmentation and donor transaction costs. Econ. Lett. 2012, 117, 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Koenig-Archibugi, M. Aid fragmentation or aid pluralism? The effect of multiple donors on child survival in developing countries, 1990–2010. World Dev. 2015, 76, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, J.; Guarin, A.; Frommé, E.; Pauw, P. Deforestation and the Paris climate agreement: An assessment of REDD+ in the national climate action plans. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 90, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Voluntary REDD+ Database; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Overseas Development Institute Climate Funds Update. Available online: http://www.climatefundsupdate.org/themes (accessed on 1 July 2021).

| Implementation Phase | Activities |

|---|---|

| Phase 1: Readiness |

|

| Phase 2: Implementation |

|

| Phase 3: Result-based payments |

|

| Characteristics | Kyoto Protocol | Paris Agreement |

|---|---|---|

| Period |

|

|

| Emissions Reduction Obligations |

|

|

| REDD+ financing |

|

|

| Characteristics | Bilateral | Multilateral | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of donors | 16 | 9 | 25 |

| Number of recipient countries | 88 | 91 | 108 |

| Number of donor–recipient relationships (cases) | 264 | 193 | 457 |

| Amount of commitment (million USD) | 6197.68 | 3501.59 | 9699.27 |

| Share of total commitment amount (%) | 63.90 | 36.10 | 100.00 |

| Major Forest Type | Recipient Countries (n) | Relationships (n) | Significant Relationships (n) | Insignificant Relationships (n) | Fragmentation Rate (%) | Committed Amount (M USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tropical | 87 | 412 | 319 | 93 | 22.57 | 8881.21 |

| Sub-tropical | 13 | 29 | 24 | 5 | 17.24 | 727.80 |

| Temperate and Boreal | 8 | 16 | 14 | 2 | 12.50 | 90.25 |

| Global | 108 | 457 | 357 | 100 | 21.88 | 9699.27 |

| Quadrant | Number of Recipients | Number of Donors | Allocated Amount (Million USD) | ln (Amounts) | Fragmentation (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Ⅰ | 2 | 13.00 | 0.00 | 316.33 | 54.99 | 5.75 | 0.17 | 30.77 | 10.88 |

| Ⅱ | 32 | 6.59 | 2.71 | 206.50 | 395.91 | 4.58 | 1.12 | 38.62 | 15.85 |

| Ⅲ | 73 | 2.82 | 2.06 | 20.55 | 28.81 | 2.07 | 1.54 | 2.55 | 6.20 |

| Ⅳ | 1 | 14.00 | - | 958.37 | - | 6.87 | - | 7.14 | - |

| Type of REDD+ Finance | Number of Donors | Number of Recipients | Amounts | Fragmentation (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Bilateral | 16 | 17 | 14.50 | 387.36 | 626.00 | 28.41 | 15.61 |

| Multilateral | 9 | 21 | 26.60 | 389.07 | 474.24 | 12.95 | 10.42 |

| Group | Number of Countries | Numberof Donors | Allocated Amounts | Fragmentation (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Group I | 11 | 7.18 | 3.37 | 345.95 | 668.37 | 21.71 | 20.85 |

| Group II | 36 | 6.11 | 3.16 | 118.44 | 145.99 | 24.74 | 22.16 |

| Group III | 15 | 3.33 | 1.88 | 25.58 | 25.49 | 11.84 | 14.64 |

| Group IV | 46 | 2.35 | 2.09 | 27.09 | 88.00 | 4.00 | 11.76 |

| Classification | Phase I | Phase II | Phase III |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developing WRF elements | Benin, Central African Republic, Chad, Cuba, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Malawi, Mali, Namibia, Saint Lucia, Thailand, Togo, Uruguay, Vanuatu | Bangladesh, Belize, Bhutan, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Dominican Republic, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea Bissau, Guyana, Honduras, India, Kenya, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Liberia, Madagascar, Mexico, Mongolia, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Suriname, United Republic of Tanzania, Vietnam, Zambia | |

| Provision of result-based payments | Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Uganda | ||

| Engaging in Cooperative approaches |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, D.-h.; Kim, D.-h.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, R. Fragmentation and Coordination of REDD+ Finance under the Paris Agreement Regime. Forests 2021, 12, 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12111452

Kim D-h, Kim D-h, Kim HS, Kim R. Fragmentation and Coordination of REDD+ Finance under the Paris Agreement Regime. Forests. 2021; 12(11):1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12111452

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Dong-hwan, Do-hun Kim, Hyun Seok Kim, and Raehyun Kim. 2021. "Fragmentation and Coordination of REDD+ Finance under the Paris Agreement Regime" Forests 12, no. 11: 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12111452

APA StyleKim, D.-h., Kim, D.-h., Kim, H. S., & Kim, R. (2021). Fragmentation and Coordination of REDD+ Finance under the Paris Agreement Regime. Forests, 12(11), 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12111452