The PING Project: Using Ecological Momentary Assessments to Better Understand When and How Woodland Owner Group Members Engage with Their Woodlands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feasibility Test

2.2. Pilot Study

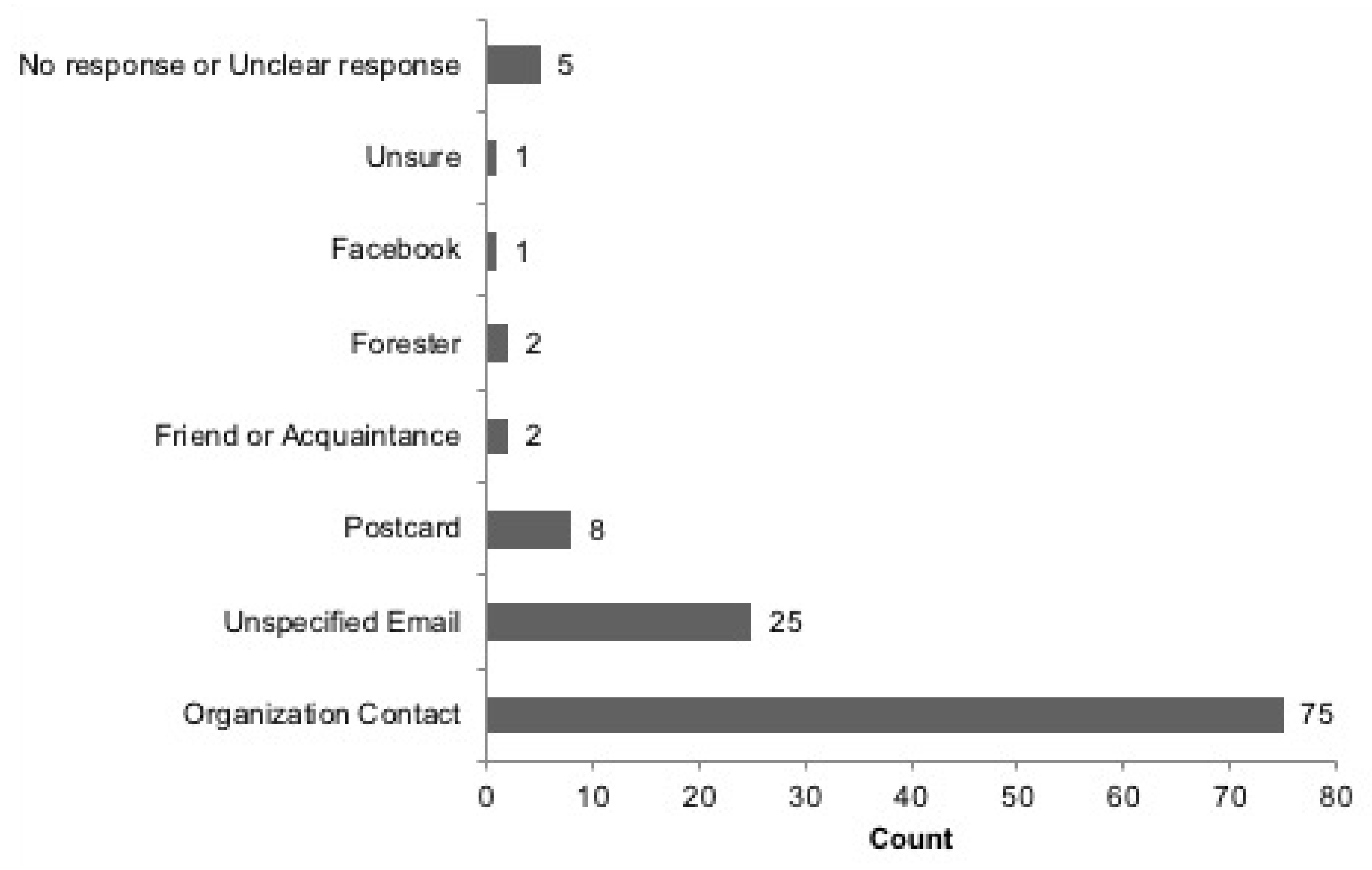

2.2.1. Participant Recruitment

2.2.2. Survey Design

2.2.3. Ecological Momentary Assessments

3. Results

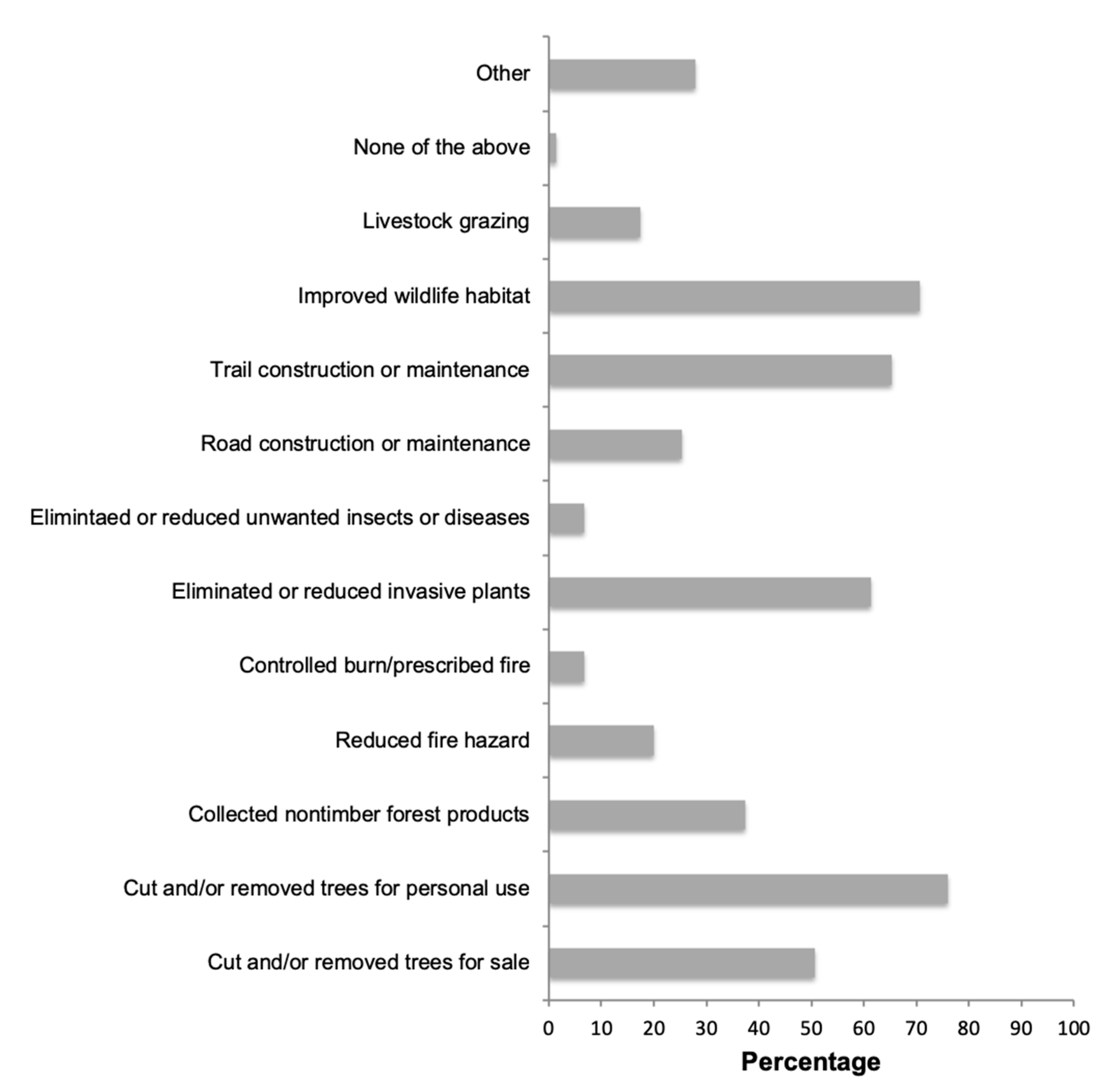

3.1. Initial Survey

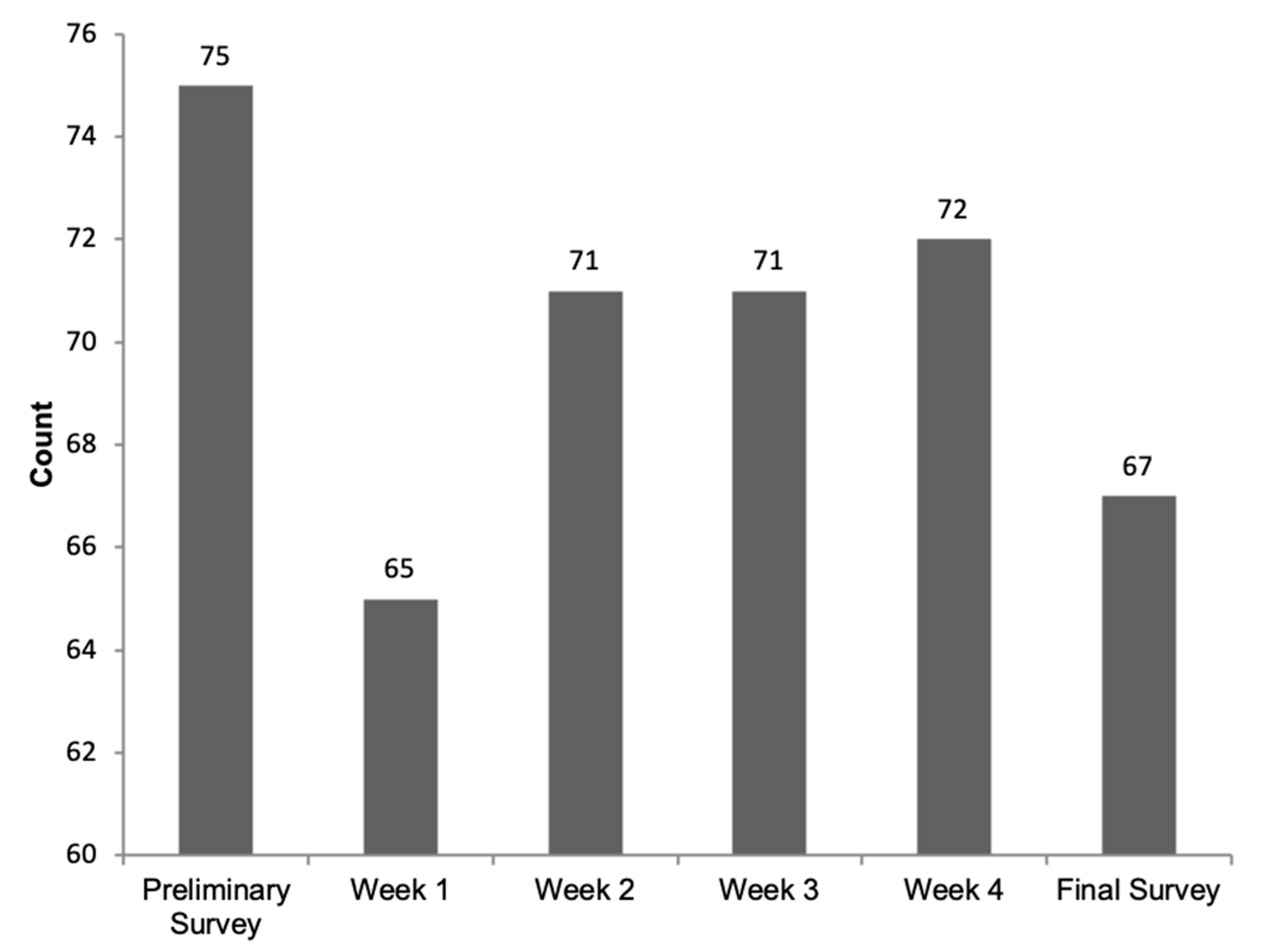

3.2. Weekly Contacts

3.3. Evaluation Survey

4. Discussion

4.1. Recruitment and Attrition

4.2. Levels of FFO Engagement

4.3. Evaluation

4.4. Study Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smyth, J.M.; Stone, A.A. Ecological Momentary Assessment Research in Behavioral medicine. J. Happ. Stud. 2003, 4, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffman, S.; Stone, A.A.; Hufford, M.R. Ecological Momentary Assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runyan, J.D.; Steenbergh, T.A.; Bainbridge, C.; Daugherty, D.A.; Oke, L.; Fry, B.N. A Smartphone Ecological Momentary Assessment/Intervention “App” for Collecting Real-Time Data and Promoting Self-Awareness. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, N. Retrospective and concurrent self-reports: The rationale for real-time data capture. In Stone: The Science of Real-Time Data Capture: Self-Reports in Health Research; Shiffman, A., Atienza, S.A., Nebeling, L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrant, M.A.; Manfredo, M.J.; Bayley, P.B.; Hess, R. Effects of Recall Bias and Nonresponse Bias on Self-Report Estimates of Angling Participation. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 1993, 13, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffman, S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 21, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, S.L.; Dimeff, L.A.; Skutch, J.; Carroll, D.; Linehan, M.M. A Pilot Study of the DBT Coach: An Interactive Mobile Phone Application for Individuals with Borderline Personality Disorder and Substance Use Disorder. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, B.J.; Hewes, J.H.; Dickinson, B.; Andrejczyk, K.; Butler, S.M.; Markowski-Lindsay, M. USDA Forest Service National Woodland Owner Survey: National, Regional, and State Statistics for Family Forest and Woodland Ownerships with 10+ Acres, 2011–2013; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.P.; Bliss, J.; Ingemarson, F.; Lidestav, G.; Lönnstedt, L. From the small woodland problem to ecosocial systems: The evolution of social research on small-scale forestry in Sweden and the USA. Scand. J. For. Res. 2010, 25, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, A.F.; Jones, S.B. The Reliability of Landowner Survey Responses to Questions on Forest Ownership and Harvesting. North. J. Appl. For. 1995, 12, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, E.J.; Leahy, J.E.; Weiskittel, A.; Noblet, C.L.; Kittredge, D.B. An Evidence-Based Review of Timber Harvesting Behavior among Private Woodland Owners. J. For. 2015, 113, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Joyce, N.; Sheikh, S.; Cote, N.G. Knowledge and the Prediction of Behavior: The Role of Information Accuracy in the Theory of Planned Behavior. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 33, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, E.S.; Leahy, J.E.; Kittredge, D.B.; Noblet, C.L.; Weiskittel, A. Psychological distance of timber harvesting for private woodland owners. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 81, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hujala, T.; Pykäläinen, J.; Tikkanen, J. Decision making among Finnish non-industrial private forest owners: The role of professional opinion and desire to learn. Scand. J. For. Res. 2007, 22, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.P. Internal and External Influences on Water Resource Decision Making. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2015, 29, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.P. Social, Institutional, and Psychological Factors Affecting Wildfire Incident Decision Making. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2014, 27, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B.J.; Tyrrell, M.; Feinberg, G.; VanManen, S.; Wiseman, L.; Wallinger, S. Understanding and reaching family forest owners: Lessons from social marketing research. J. For. 2007, 105, 348–357. [Google Scholar]

- PEW Research Center. Mobile Fact Sheet. Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/ (accessed on 12 March 2018).

- Connelly, N.A.; Brown, T.L.; Decker, D.J. Factors Affecting Response Rates to Natural Resource-Focused Mail Surveys: Empirical Evidence of Declining Rates Over Time. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickenbach, M.G.; Guries, R.P.; Schmoldt, D.L. Membership matters: Comparing members and non-members of NIPF owner organizations in southwest Wisconsin, USA. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, J.E., Jr.; Straka, T.J.; Cushing, T.L.; Greene, J.L.; Bridges, W.C. Socioeconomic predictors of family forest owner use of U.S. Federal income tax provisions. Forests 2016, 7, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floress, K.; Huff, E.S.; Snyder, S.A.; Koshollek, A.; Butler, S.; Allred, S.B. Factors associated with family forest owner actions: A vote-count meta-analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 188, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.E.; van den Berg, A.E.; de Groot, J.I. Environmental Psychology: An Introduction; BPS Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn, N. Response effects. In Handbook of Survey Research; Rossi, P.H., Wright, S.D., Anderson, A.B., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 289–327. [Google Scholar]

- FCC. Internet Access Services: Status as of 12/31/2016. Federal Communications Commission, 2016. Available online: https://www.fcc.gov/general/iatd-data-statistical-reports (accessed on 25 July 2018).

| Survey | Question | Answer Choices |

|---|---|---|

| Initial survey | How many acres of wooded land do you own? | Open response |

| Is your home or primary residence on or within your wooded land? | Yes/no/not applicable | |

| Which of the following have occurred on your wooded land in the past 5 years? | Cut or removed trees for sale, cut or removed trees for personal use, collected nontimber forest products, reduced fire hazard, controlled burn/prescribed fire, eliminated or reduced invasive plants or insects, road/trail construction or maintenance, improved wildlife habitat, livestock grazing, none of the above, other | |

| In what year were you born? | Open response | |

| What gender do you identify as? | Male, female, agender, other, prefer not to answer | |

| What is the highest level of education you have completed? | High school, some college, Associate’s degree, Vocational degree, Bachelor’s degree, Master’s degree, Doctorate’s degree, other | |

| How do you prefer to receive weekly survey questions? | E-mail, Facebook, Twitter, withdraw participation | |

| How did you hear about this study? | Open response | |

| Weekly Survey | Which of the following have occurred on your wooded land in the past 48 h? | List of activities above and made a decision about my woodland, talked to someone about my woodland, walked in my woodland, thought about my woodland |

| Evaluation survey | Did this project make you think more about your woods than you would have otherwise? | Yes/no/please explain |

| How representative were your answers of the typical week? | 1–5 Likert scale | |

| Was your answer affected by the season we are currently in? | Yes/no, If so, how? | |

| Are there any activities related to your woodlands that you participate in but weren’t included in the survey questions? | Open response | |

| Please select all that apply regarding the burden level of this study. | I found the multiple, weekly contacts burdensome, I found the number of questions burdensome, I found the method of contact burdensome, I found the multiple, weekly contacts reasonable, I found the number of questions reasonable, I found the method of contact reasonable. | |

| Please share any further thoughts about this online survey method and/or your engagement with your woods below. | Open response |

| Management Activities | Week 1 (%) | Week 2 (%) | Week 3 (%) | Week 4 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut timber for sale | 5.5 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 4.1 |

| Cut timber for personal use | 13.7 | 8.2 | 6.9 | 2.7 |

| Collected nontimber products | 5.5 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 6.9 |

| Reduced fire hazard | 4.1 | 6.8 | 4.1 | 0.0 |

| Controlled burn/prescribed fire | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Eliminated/reduced invasive plants | 20.5 | 21.9 | 23.3 | 16.4 |

| Eliminated/reduced unwanted insects/diseases | 1.4 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| Road construction or maintenance | 9.6 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 4.1 |

| Trail construction or maintenance | 17.8 | 16.4 | 8.2 | 9.6 |

| Improved wildlife habitat | 15.1 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 8.2 |

| Livestock grazing | 4.1 | 4.1 | 5.5 | 6.8 |

| Decision about woodland | 13.7 | 9.6 | 6.9 | 13.7 |

| Talked about woodland | 31.5 | 37.0 | 31.5 | 32.9 |

| Walked in woodland | 46.6 | 49.3 | 34.2 | 39.7 |

| Thought about woodland | 47.9 | 50.7 | 48.0 | 41.1 |

| Other | 4.1 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 16.4 |

| None of the above | 10.96 | 0.00 | 12.33 | 10.96 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huff, E.S.; Kittredge, D.B. The PING Project: Using Ecological Momentary Assessments to Better Understand When and How Woodland Owner Group Members Engage with Their Woodlands. Forests 2020, 11, 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11090944

Huff ES, Kittredge DB. The PING Project: Using Ecological Momentary Assessments to Better Understand When and How Woodland Owner Group Members Engage with Their Woodlands. Forests. 2020; 11(9):944. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11090944

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuff, Emily S., and David B. Kittredge. 2020. "The PING Project: Using Ecological Momentary Assessments to Better Understand When and How Woodland Owner Group Members Engage with Their Woodlands" Forests 11, no. 9: 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11090944

APA StyleHuff, E. S., & Kittredge, D. B. (2020). The PING Project: Using Ecological Momentary Assessments to Better Understand When and How Woodland Owner Group Members Engage with Their Woodlands. Forests, 11(9), 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11090944