Embedded Deforestation: The Case Study of the Brazilian–Italian Bovine Leather Trade

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Embedded Deforestation in Current Global Trade and Finance

2. Materials and Methods

- For the country-level leather trade between Brazil and Italy: annual leather trade statistics between Brazil and Italy, at the national level, for the years 2014–2018, in net weight (kg). This data is based on the public UN Comtrade database that is a repository for official international trade statistics;

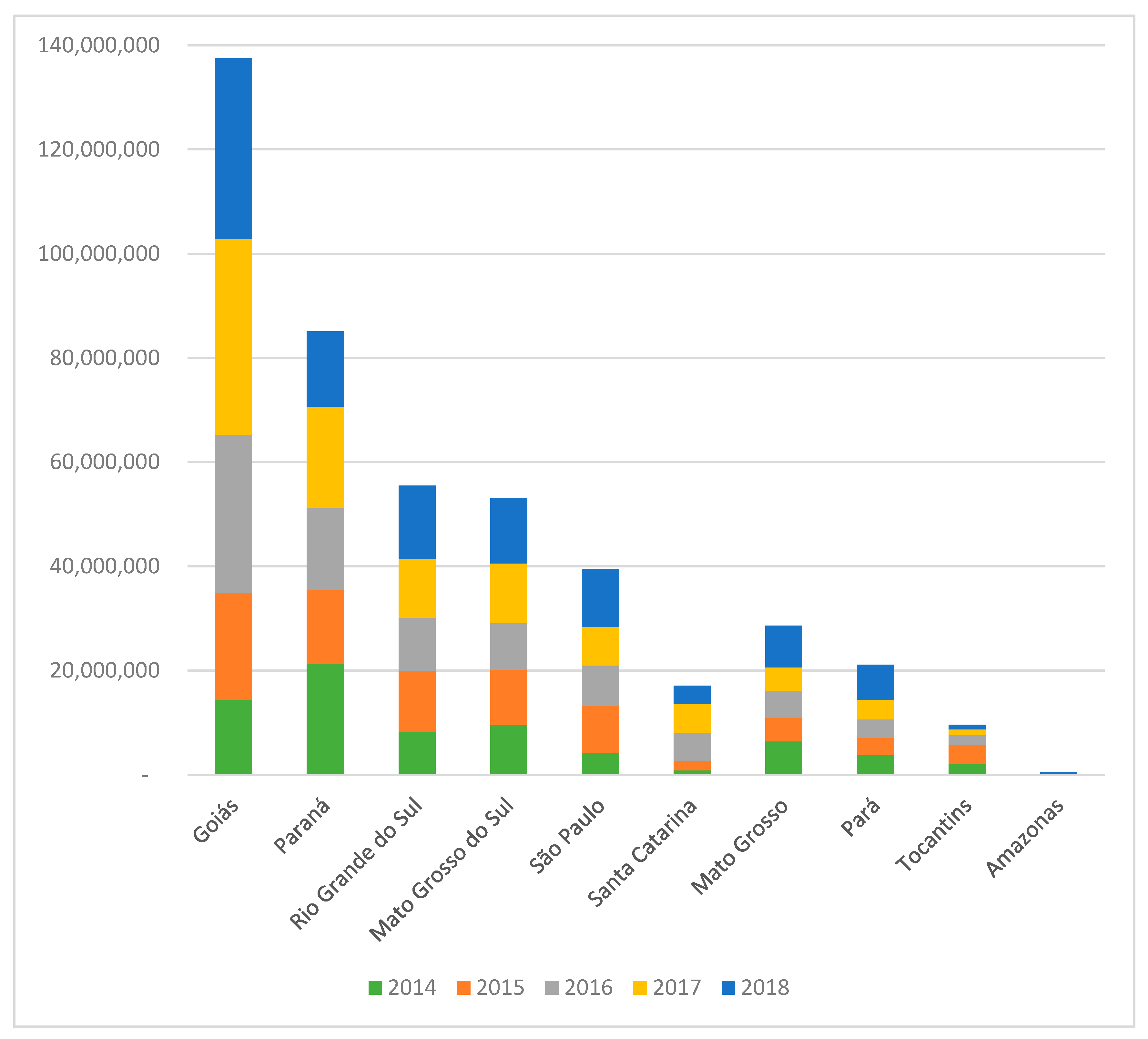

- for the state-level leather trade between Brazil and Italy: the state level leather exports from Brazil in general and the exports by Brazilian states to Italy, for the years 2014–2018, in net weight (kg). This data is based on the Comexstat database (previously, Aliceweb), the official and public Brazilian foreign trade statistics portal that allows obtaining subnational (state and municipal) level export data. The Comexstat database [41] allows filtering out exporting states and exported product categories. With regard to the origin states, we were interested in understanding the share of BLA leather exports within the total exports from the country. The municipal-level export data from Comexstat was used additionally to confirm the exports by individual exporting companies;

- for the exporter–importer-level leather trade between Brazil and Italy: leather trade statistics between Brazil and Italy, at the individual shipment level, for the period August 2017–August 2018, in metric tons. This is based on customs declarations. Among many, the customs declarations contain the information on the date of export, exporter, product (volume or value), a port of export, country of destination and the importer (consignee – an entity who is financially responsible for the receipt of a shipment). We were able to obtain the data covering only one fiscal year.

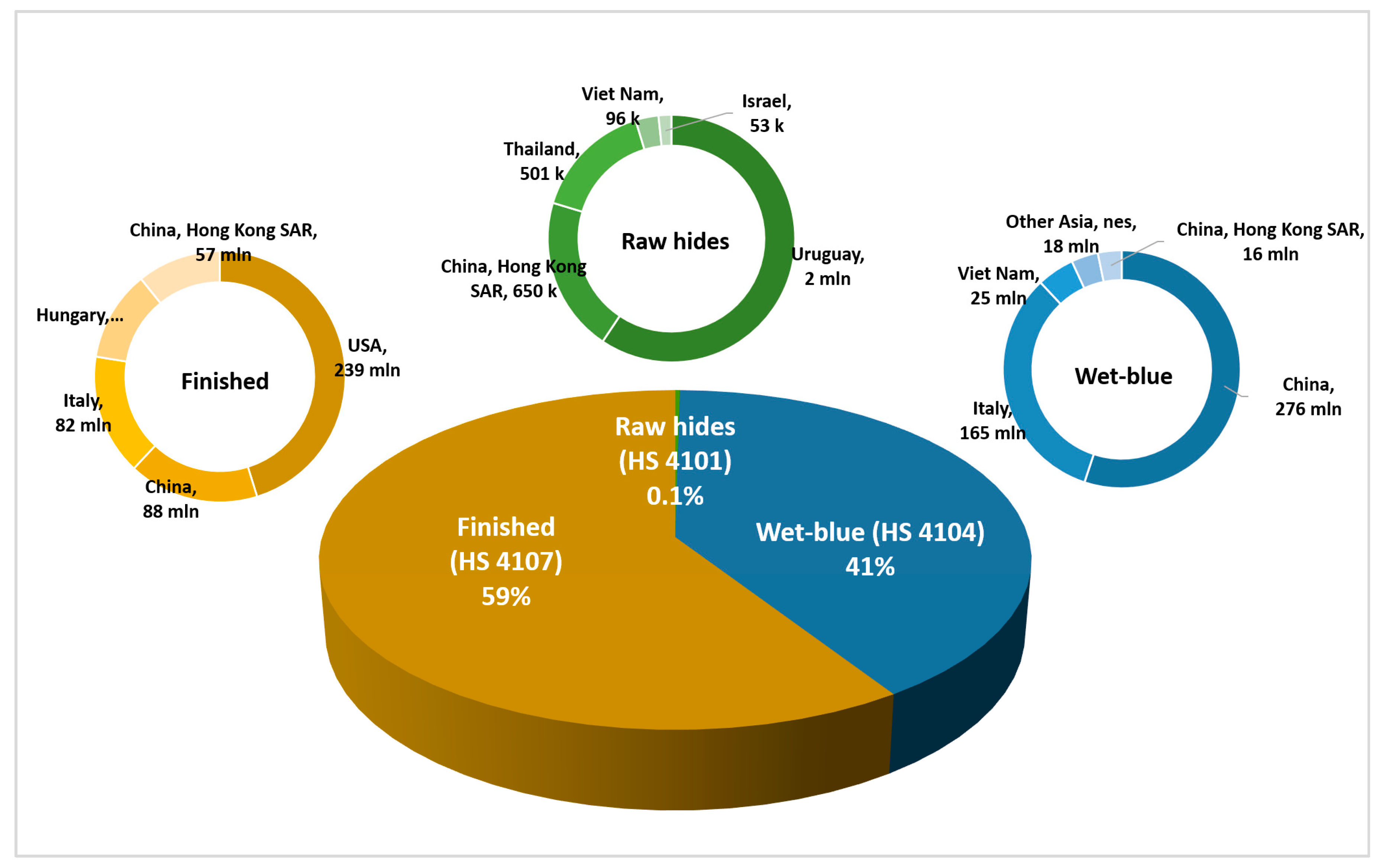

- HS 4101—raw hides and skins of bovine (including buffalo) or equine animals (fresh, salted, dried, limed, pickled, otherwise preserved but not tanned, parchment dressed or further prepared), whether or not dehaired or split—hereinafter raw or salted hides;

- HS 4104—tanned or crust hides and skins of bovine (including buffalo) or equine animals, without hair on, whether or not split, but not further prepared—hereinafter wet-blue or semi-processed leather;

- HS 4107—leather further prepared after tanning or crusting, including parchment-dressed leather, of bovine (including buffalo) or equine animals, without hair on, whether or not split, other than leather of heading 41.14—hereinafter finished leather.

3. Results

3.1. Assessing Deforestation Risk through Trade Data Analysis

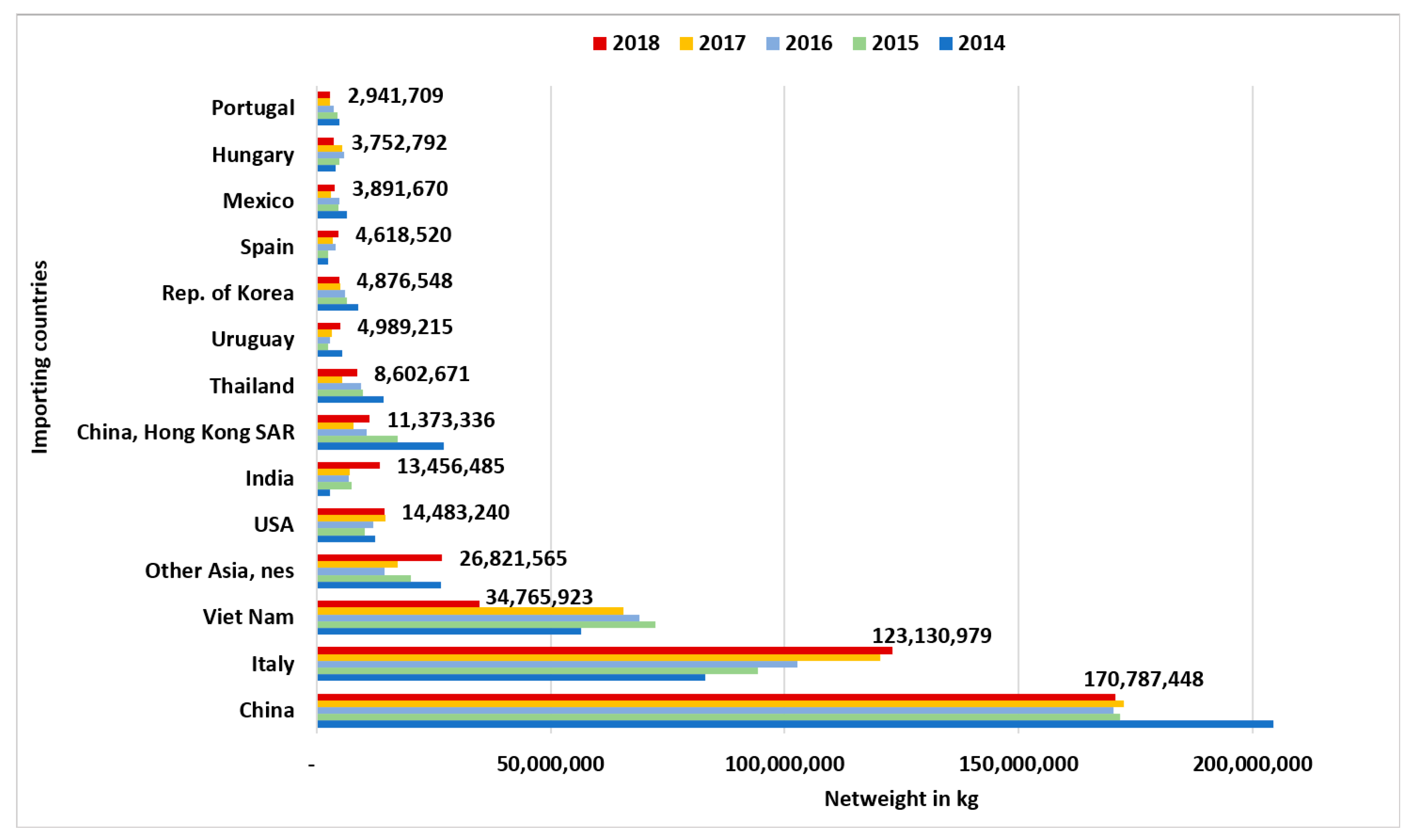

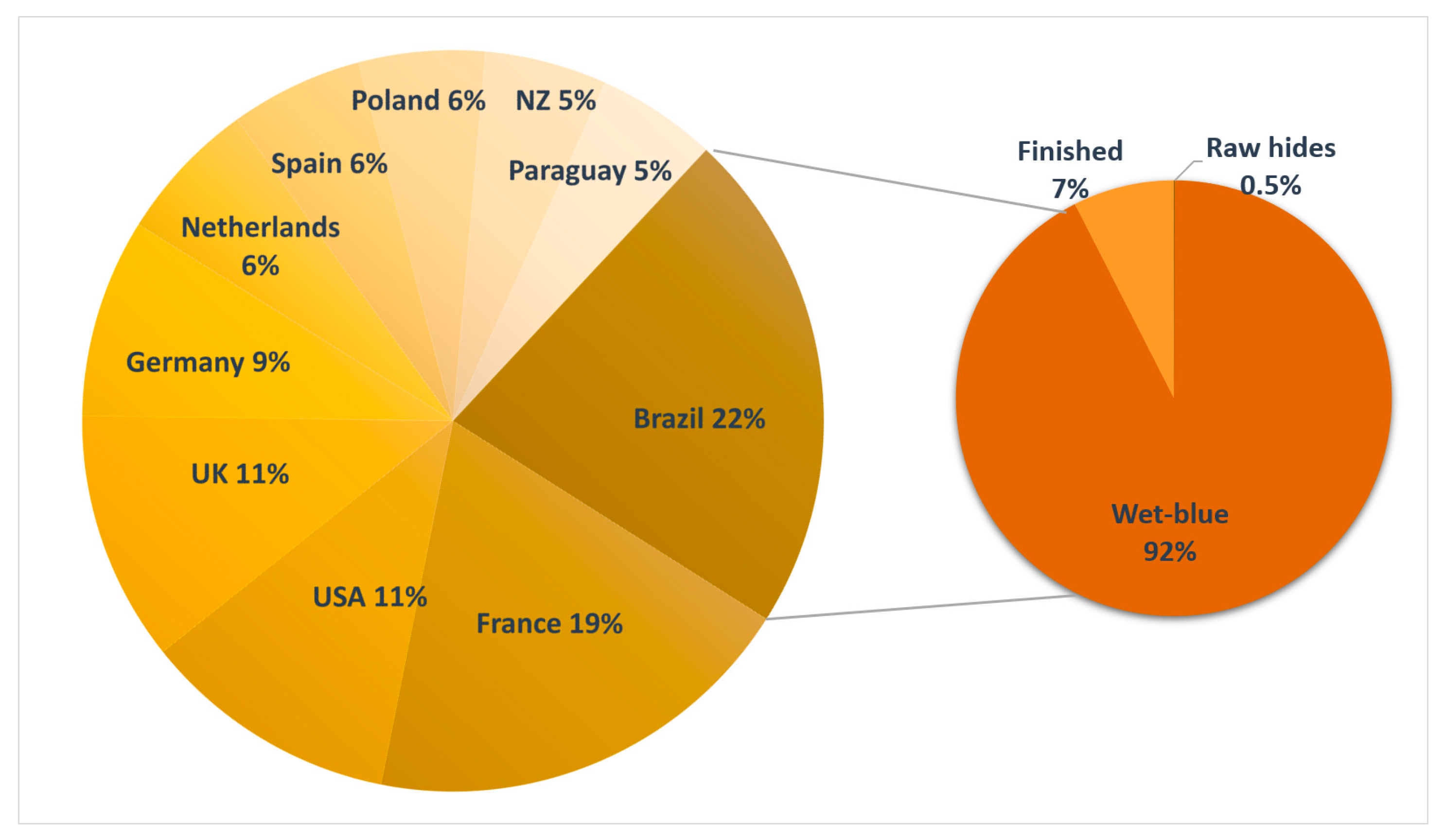

3.1.1. Country-Level Leather Trade between Brazil and Italy

3.1.2. State-Level Leather Trade between Brazil and Italy

3.1.3. Exporter–Importer-Level Leather Trade between Brazil and Italy

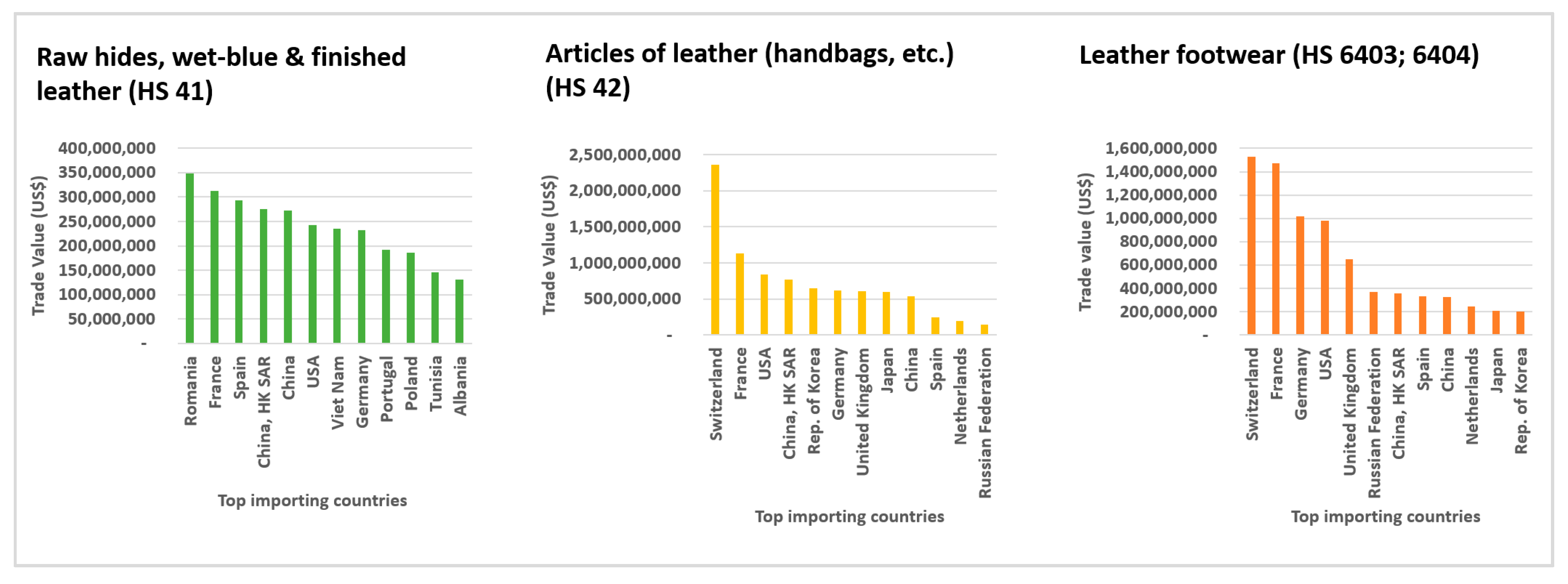

3.1.4. Final Destination of Italian Leather Products

3.2. Deforestation as the Legal and Reputational Risk

3.2.1. Reputational Risk

3.2.2. Legal or Regulatory Risk

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

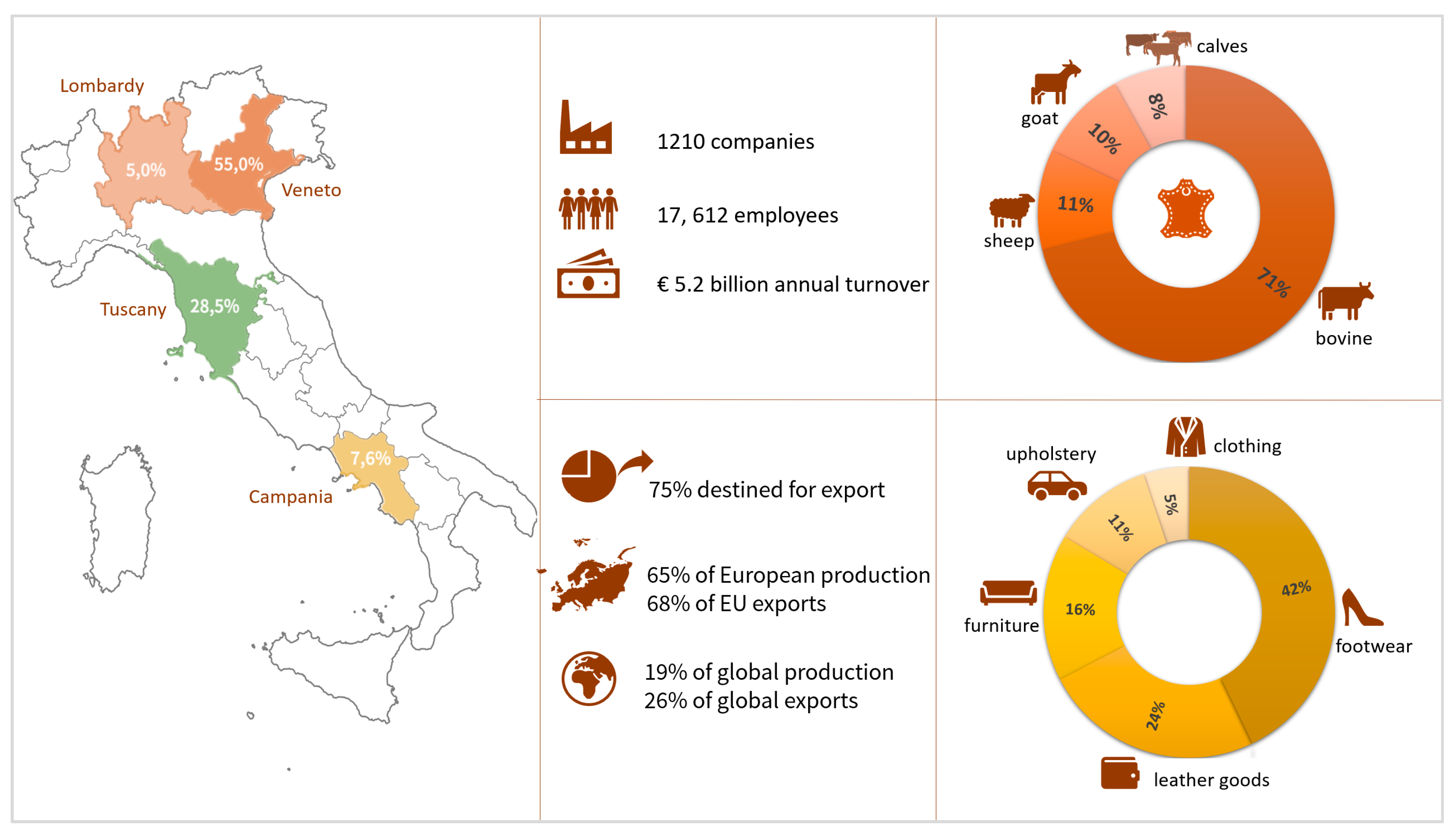

Appendix A. Additional Information about the Italian Leather Industry

- Arzignano and Chiampo valley from Crespadoro to Montebello, from Montorso to Zermeghedo and Montecchio Maggiore (Vicenza, Veneto—north-east Italy);

- Santa Croce Sull’Arno and Ponte a Egola (Pisa, Tuscany—center-west Italy);

- Solofra (Avellino, Campania—south Italy);

- Turbigo (Milan, Lombardy—north-west Italy).

Appendix B

| HS2 | 41–43. Raw Hides, Skins, Leather, & Furs | 41. Raw hides and skins (other than fur skins) and leather | |||||

| 42. Articles of leather; saddlery and harness; travel goods, handbags and similar containers; articles of animal gut (other than silk-worm gut) | |||||||

| 43. Fur skins and artificial fur; manufactures thereof | |||||||

| HS2 | Description | HS4 | Description | HS6 | Description | HS8 | Description |

| 41 | Raw hides and skins (other than fur skins) and leather | 4101 | Raw hides and skins of bovine (including buffalo) or equine animals (fresh, or salted, dried, limed, pickled or otherwise preserved, but not tanned, parchment-dressed or further prepared), whether or not dehaired or split | 410110 | Raw skins of bovine, whole, when dried <= 8 kg, etc. | 41011000 | Raw skins of bovine, whole, when dried <= 8 kg, etc. |

| 410120 | Whole raw hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, whether or not dehaired or split, of a weight per skin <= 8 kg when simply dried, <= 10 kg when dry-salted, or <= 16 kg when fresh, wet-salted or otherwise preserved (excl. tanned and pa | 41012000 | Raw hides and skins, whole, with weight restriction | ||||

| 41012010 | Whole leathers/skin of bovine, n/divided w <= 8 kg | ||||||

| 41012020 | Divid./whol.leathers/skin, bovine, grain splits, w <= 8 kg | ||||||

| 41012030 | Divid./whol.leat./skin, bovine, splits(than grain)w <= 8 kg | ||||||

| 410121 | Whole hides and skins of bovine animals (fresh or wet-salted) | 41012110 | Raw skins of bovine, whole, n/divided, fresh, etc. | ||||

| 41012120 | Raw skins of bovine, whole, grain splits, fresh, etc. | ||||||

| 41012130 | Raw skins of bov. whole, splits(than grain spl.)fresh, etc. | ||||||

| 410122 | Buttes and bends (skins of bovine animals) | 41012210 | Raw skins of bovine, (backs), not slipt, fresh, etc. | ||||

| 41012220 | Raw skins of bovine, (backs), grain splits, fresh, etc. | ||||||

| 41012230 | Raw skins of bovine, (backs), slipts (than grain) fresh, etc. | ||||||

| 410129 | Other hides and skins of bovine animals (fresh or wet-salted) | 41012910 | Oth. raw skins of bov.(backs), n/slipt, fresh, etc. | ||||

| 41012920 | Oth. raw skins of bovine, (backs), grain splits, fresh, etc. | ||||||

| 41012930 | Ot. raw skins of bovine, slipts(than grain spl.)fresh, etc. | ||||||

| 41013010 | Raw skins of bovine, conser.of another way, not slipt | ||||||

| 41013020 | Raw skins, of bovine, conser.of another way, grain splits | ||||||

| 41013030 | Raw skins of bovine, cons.another way slipts (than grain) | ||||||

| 410150 | Whole raw hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, whether or not dehaired or split, of a weight per skin > 16 kg, fresh, or salted, dried, limed, pickled or otherwise preserved (excl. tanned, parchment-dressed or further prepared) | 41015010 | Whole leathers/skin of bovine, not split, w <= 16 kg | ||||

| 41015020 | Whole leathers/skin, bovine, grain splits, w <= 16 kg | ||||||

| 41015030 | Whole leath./skin, bov. slipts (ot. than grain sp.), w <= 16 kg | ||||||

| 410190 | Butts, bends, bellies and split raw hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, whether or not dehaired, fresh, or salted, dried, limed, pickled or otherwise preserved, and whole raw hides and skins of a weight per skin > 8 kg but < 16 kg w | 41019010 | Other leathers/skin, bovine, not split | ||||

| 41019020 | Other leathers/skin, of bovine, grain splits | ||||||

| 41019030 | Raw skins of bovine, cons. another way slipts (than grain) | ||||||

| 4104 | Tanned or crust hides and skins of bovine (including buffalo) or equine animals, without hair on, whether or not split, but not further prepared | 410410 | Whole bovine skin leather | 41041011 | Leathers/skin whole, bovine, s <= 2.6 m2, “wet blue”, n/spl | ||

| 41041012 | Leathers/skin whole, bovine, s <= 2.6 m2, “wet blue”, grain sl | ||||||

| 41041013 | Leathers/skin whole, bov.s <= 2.6 m2, “wet blue”, splits(than | ||||||

| 41041020 | Leathers/skin whole, bovine, s <= 2.6m2, “box-calf” | ||||||

| 41041090 | Oth. leathers/skins whole, bovine, s <= 2.6 m2, prepared | ||||||

| 410411 | Full grains, unsplit and grain splits, in the wet state incl. wet-blue, of hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, tanned, without hair on (excl. further prepared) | 41041111 | Whole leathers of bovines, n/split “wet blue”, s <= 2.6 m2 | ||||

| 41041112 | Whole leath. of bovines, slipts (than grain split) <= 2.6 m2 | ||||||

| 41041113 | Oth. leathers of bovines, n/slipt wet pre-tanned, veg. | ||||||

| 41041114 | Oth. leathers bovines, incl. buffalos, wet split(than grain | ||||||

| 41041121 | Whole leathers of bovine, split” wet blue”, s <= 2.6 m2 | ||||||

| 41041122 | Whole leathers of bovines, grain splits s <= 2.6 m2 | ||||||

| 41041123 | Oth. tanned bovine, split, wet, veget pre-tanned | ||||||

| 41041124 | Other leathers bovines, incl. buffalos, wet, grain splits | ||||||

| 410419 | Hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, in the wet state incl. wet-blue, tanned, without hair on, whether or not split (excl. further prepared and full grains, unsplit and grain splits) | 41041910 | Other whole leathers of bovines, “wet blue”, s <= 2.6 m2 | ||||

| 41041920 | Oth. leathers/skins, whole, bovines, wet states <= 2.6 m2 | ||||||

| 41041930 | Oth. leathers/skins, bovines, wet state veg.pre-tanned | ||||||

| 41041940 | Other leathers/skins, bovines, including buffalos, wet | ||||||

| 410421 | Leathers/skins, bovines, vegetable pre-tanned | 41042100 | Leathers/skins, bovines, vegetable pre-tanned | ||||

| 410422 | Bovine leather (otherwise pre-tanned) | 41042211 | Leathers/skins, whole/half, bovines, wet blue, n/split | ||||

| 41042212 | Leathers/skins, whole/half, bovines, wet blue, grain split | ||||||

| 41042213 | Leathers/skins, whole/half, bovines, wet blue, split (than g | ||||||

| 41042219 | Other leathers/skins, bovines, “wet blue” | ||||||

| 41042290 | Oth. leathers, bovines, pre-tanned of other way | ||||||

| 410429 | Other leathers/skins, of bovines/equine, tanned or retanned | 41042900 | Oth. leathers/skins, of bovines/equine, tanned or retanned | ||||

| 410431 | Other bovine leather and equine leather (full grains and grain splits) | 41043111 | Leat./skins, bovin.veg.pre-tann. for soles, grain split n/fi | ||||

| 41043119 | Ot.leat./skins, bov.pre-tan.prepar.grain split n/finis. | ||||||

| 41043120 | Leat./skins, bov.after tann.prepar.grain split n/finis. | ||||||

| 41043190 | Ot. leat./skins, bov./equine pre-tan. prepar. grain split | ||||||

| 410439 | Other bovine leather and equine leather (parchment-dressed) | 41043911 | Ot. leat./skins, bovine after-tann. prepar. n/finishing | ||||

| 41043912 | Ot.leat./skins, bovine, after-tann. prepar. with finishing | ||||||

| 41043990 | Oth. leath./skins, bovine/equine, parchment-dressed | ||||||

| 410441 | Full grains leather, unsplit and grain splits leather, in the dry state crust, of hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, without hair on (excl. further prepared) | 41044110 | Whole leath. of bovines, dry state, grain splits s <= 2.6 m2 | ||||

| 41044120 | Leat. of bovines, dry state, grain sp.tanned, for use as sole | ||||||

| 41044130 | Other leathers/skins of bovines, dry state, grain slipts | ||||||

| 410449 | Hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, in the dry state crust, without hair on, whether or not split (excl. further prepared and full grains, unsplit and grain splits) | 41044910 | Other leathers/skins, of bovines, dry state, s <= 2.6 m2 | ||||

| 41044920 | Other leathers/skins of bovines, dry state | ||||||

| 4107 | Leather further prepared after tanning or crusting, including parchment-dressed leather, of bovine (including buffalo) or equine animals, without hair on, whether or not split, other than leather of heading 4114 | 410711 | Full grains leather incl. parchment-dressed leather, unsplit, of the whole hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, further prepared after tanning or crusting, without hair on (excl. chamois leather, patent leather and patent laminated l | 41071110 | Whole leathers of bovines, full grains, prepared s <= 2.6 m2 | ||

| 41071120 | Oth. whole leathers/skins of bovines, full grain. prepar. | ||||||

| 410712 | Grain splits leather incl. parchment-dressed leather, of the whole hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, further prepared after tanning or crusting, without hair on (excl. chamois leather, patent leather and patent laminated leather, | 41071210 | Whole leathers/skins of bovines, prepared s <= 2.6 m2 | ||||

| 41071220 | Oth. whole leathers/skins of bovines, prepared, etc. | ||||||

| 410719 | Leather incl. parchment-dressed leather of the whole hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, further prepared after tanning or crusting, without hair on (excl. unsplit full grains leather, grain splits leather, chamois leather, patent l | 41071910 | Whole leathers/skins of bovines, prepared s <= 2.6 m2 | ||||

| 41071920 | Oth. whole leathers/skins of bovines, prepared | ||||||

| 410791 | Full grains leather incl. parchment-dressed leather, unsplit, of the portions, strips or sheets of hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, further prepared after tanning or crusting, without hair on (excl. chamois leather, patent leath | 41079110 | Whole skins of bovines, prepar. full grains, unsplit | ||||

| 410792 | Grain splits leather incl. parchment-dressed leather, of the portions, strips or sheets of hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, further prepared after tanning or crusting, without hair on (excl. chamois leather, patent leather and p | 41079210 | Leathers/skins, bovines, prepared, grain splits | ||||

| 410799 | Leather incl. parchment-dressed leather of the portions, strips or sheets of hides and skins of bovine incl. buffalo or equine animals, further prepared after tanning or crusting, without hair on | 41079910 | Other leathers/skins, bovines, prepared | ||||

References

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Campbell, B.M.; Ingram, J.S.I. Climate Change and Food Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolosin, M.; Harris, N. Tropical Forests and Climate Change: The Latest Science; Working Paper; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: wri.org/ending-tropical-deforestation (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Calvo Buendia, E., Masson-Delmotte, V., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Zhai, P., Slade, R., Connors, S., et al., Eds.; In press. 2019. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/4/2020/02/SPM_Updated-Jan20.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Cuypers, D.; Lust, A.; Geerken, T.; Gorissen, L.; Peters, G.; Karstensen, J.; Prieler, S.; Fisher, G.; Hizsnyik, E.; Van Velthuizen, H.; et al. The Impact of EU Consumption on Deforestation: Comprehensive Analysis of the Impact of EU Consumption on Deforestation: Final Report; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, H.K.; Ruesch, A.S.; Achard, F.; Clayton, M.K.; Holmgren, P.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Tropical forests were the primary sources of new agricultural land in the 1980s and 1990s. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16732–16737. Available online: https://www.pnas.org/content/107/38/16732.short (accessed on 11 February 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosonuma, N.; Herold, M.; Sy, V.D.; Fries, R.S.D.; Brockhaus, M.; Verchot, L.; Angelsen, A.; Romijn, E. An Assessment of Deforestation and Forest Degradation Drivers in Developing Countries. Environ. Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 044009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepstad, D.; McGrath, D.; Stickler, C.; Alencar, A.; Azevedo, A.; Swette, B.; Bezerra, T.; DiGiano, M.; Shimada, J.; Motta, R.S.d.; et al. Slowing Amazon Deforestation through Public Policy and Interventions in Beef and Soy Supply Chains. Science 2014, 344, 1118–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabile, M.C.; Guimarães, A.L.; Silva, D.S.; Ribeiro, V.; Macedo, M.N.; Coe, M.T.; Pinto, E.; Moutinho, P.; Alencar, A. Solving Brazil’s land use puzzle: Increasing production and slowing Amazon deforestation. Land Use Policy 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, P.; Guerra, R.; Azevedo-Ramos, C. Achieving Zero Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: What Is Missing? Elem. Sci. Anth. 2016, 4, 000125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INPE/Prodes/ TerraBrasil. Available online: http://terrabrasilis.dpi.inpe.br/en/home-page/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- James, C.H. As the Amazon burns, cattle ranchers are blamed. But it’s complicated. Natl. Geogr. 2019. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/2019/08/amazon-burns-cattle-ranchers-blamed-complicated-relationship/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- OECD/FAO. Agricultural Outlook 2017–2026; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/agr_outlook-2017-en (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Lovejoy, T.E.; Nobre, C. Amazon Tipping Point. Science Advances 2018. Available online: https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/2/eaat2340?source=post_page-----1c8e343e7f0f---------------------- (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Kaimowitz, D.; Mertens, B.; Wunder, S.; Pacheco, P. Hamburger Connection Fuels Amazon Destruction; Center for International Forest Research: Bangor, Indonesia, 2004; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rudel, T.K.; Defries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Laurance, W.F. Changing drivers of deforestation and new opportunities for conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 1396–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.D.A.; Jacinto, M.A.C.; Gomes, A.; Evaristo, L.G.S. Cadeia Produtiva Do Couro Bovino: Oportunidades E Desafios; Embrapa Gado de Corte: Campo Grande, MS, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, P.; Marianno, B.; Valdiones, A.P.; Barreto, G. Os Frigoríficos vão Ajudar a Zerar o Desmatamento na Amazônia? Imazon and Instituto Centro Da Vida. 2017. Available online: http://www.imazon.org.br/PDFimazon/Portugues/livros/Frigorificos%20e%20o%20desmatamento%20da%20Amaz%C3%B4nia.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Gibbs, H.; Munger, J.; L’Roe, J.; Barreto, P.; Pereira, R.; Christie, M.; Amaral, T.; Walker, N.F. Did ranchers and slaughterhouses respond to zero-deforestation agreements in the Brazilian Amazon? Conserv. Lett. 2016, 9, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MapBiomas. Map and Data, Land Use Change 1985–2017. Available online: http://mapbiomas.org/map#coverage (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Mammadova, A.; Behagel, J.; Masiero, M. Making deforestation risk visible. Discourses on bovine leather supply chain in Brazil. Geoforum 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC). Trade. Policy. Countries and Regions. Brazil. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/brazil/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Pendrill, F.; Persson, U.M.; Godar, J.; Kastner, T. Deforestation Displaced: Trade in Forest-Risk Commodities and the Prospects for a Global Forest Transition. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 055003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatham House. Available online: http://resourcetrade.earth/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Central Bank of Brazil. Foreign Direct Investment Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.bcb.gov.br/Rex/CensoCE/ingl/FDIReport2016.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- UN Comtrade Database. Available online: https://comtrade.un.org/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Italian Tanners Association (UNIC). Tales of Italian Leather. Sustain. Rep. 2017, 88. Available online: http://s.unic.it/5/report-en.html#20-21 (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- NYDF Assessment Partners. Protecting and Restoring Forests: A Story of Large Commitments yet Limited Progress. New York Declaration on Forests Five-Year Assessment Report. Clim. Focus 2019. Available online: forestdeclaration.org (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- FERN. EU-Mercosur Deal Sacrifices Forests and Rights on the Altar of Trade. 2019. Available online: https://www.fern.org/news-resources/eu-mercosur-deal-sacrifices-forests-and-rights-on-the-altar-of-trade-1986/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Kehoe, L.; Reis, T.; Virah-Sawmy, M.; Balmford, A.; Kuemmerle, T. Make EU Trade with Brazil Sustainable. Science 2019, 364, 341–342. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332665154_Make_EU_trade_with_Brazil_sustainable (accessed on 11 February 2020). [PubMed]

- Amazon Watch. Complicity in Destruction II. How Northern Consumers and Financiers Enable Bolsonaro’s Assault on the Brazilian Amazon; Amazon Watch: Oakland, CA, USA, 2019. Available online: https://amazonwatch.org/assets/files/2019-complicity-in-destruction-2.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Global Witness. Money to Burn. More than 300 Banks and Investors Back Six of the World’s Most Harmful Agribusinesses to the Tune of $44bn; Global Witness: Washington DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/forests/money-to-burn-how-iconic-banks-and-investors-fund-the-destruction-of-the-worlds-largest-rainforests/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Faria, W.R.; Almeida, A.N. Relationship between Openness to Trade and Deforestation: Empirical Evidence from the Brazilian Amazon. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harstad, B.; Mideksa, T.K. Conservation Contracts and Political Regimes. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2017, 84, 1708–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robalino, J.; Herrera, L.D. Trade and Deforestation: A Literature Review; WTO Staff Working Paper, No. ERSD-2010-04; World Trade Organization (WTO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, C.; Nielsen, J.Ø. Telecoupling: Exploring Land-Use Change in a Globalised World; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pendrill, F.; Persson, U.M.; Godar, J.; Kastner, T.; Moran, D.; Schmidt, S.; Wood, R. Agricultural and Forestry Trade Drives Large Share of Tropical Deforestation Emissions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 56, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, V.; Valin, H.; Krisztin, T.; Havlík, P.; Herrero, M.; Kastner, T. The Role of Trade in the Greenhouse Gas Footprints of EU Diets. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 19, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godar, J.; Persson, U.M.; Tizado, E.J.; Meyfroidt, P. Towards more accurate and policy relevant footprint analyses: Tracing fine-scale socio-environmental impacts of production to consumption. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 112, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godar, J.; Suavet, C.; Gardner, T.A.; Dawkins, E.; Meyfroidt, P. Balancing Detail and Scale in Assessing Transparency to Improve the Governance of Agricultural Commodity Supply Chains. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 035015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanemoto, K.; Moran, D.; Lenzen, M.; Geschke, A. International Trade Undermines National Emission Reduction Targets: New Evidence from Air Pollution. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 24, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests; Communication from The Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/communication-eu-action-protect-restore-forests_en.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Mammadova, A.; Sartorato, C.S.F.; Behagel, J.; Masiero, M.; Pettenella, D.M. Conceptualizing deforestation risk in commodity supply chains. The case of bovine leather. For. Policy Econom. Under Review.

- Centro das Indústrias de Curtumes do Brasil. Sobre o Couro. Available online: http://www.cicb.org.br/cicb/sobre-couro (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Anonymous. EU—Mercosur, There Is An Agreement: Raw Hides from South America (finally) Opens Its Doors. La Conceria. 4 July 2019. Available online: https://www.laconceria.it/en/news/eu-mercosur-there-is-an-agreement-raw-hides-from-south-america-finally-opens-its-doors/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Ermgassen, E.K.H.J.z.; Godar, J.; Lathuillière, M.J.; Löfgren, P.; Vasconcelos, A.; Gardner, T.; Meyfroidt, P. The Origin, Supply Chain, and Deforestation Footprint of Brazil’s Beef Exports. Available online: https://doi.org/10.31220/osf.io/efg6v (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Brazilian Leather Guide (BLG). Tannery List. 2017. Available online: http://www.guiabrasileirodocouro.com.br/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Cereceda, R.; Abellan-Matamoros, C. Brazil: State of Amazonas Declares State of Emergency over Rising Number of Forest Fires. Euronews. August 2019. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/2019/08/11/brazil-state-of-amazonas-declares-state-of-emergency-over-rising-number-of-forest-fires (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Comexstat/MDIC. Available online: http://Comexstat.mdic.gov.br/pt/home (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Ministério da Economia, Indústria, Comércio Exterior e Serviços. Empresas Brasileiras Exportadoras e Importadoras. Available online: http://www.mdic.gov.br/index.php/comercio-exterior/estatisticas-de-comercio-exterior/empresas-brasileiras-exportadoras-e-importadoras (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- The Chambers of Commerce (Le Camere di Commercio). Registro Impresse. Available online: https://www.registroimprese.it/en_US/company-registration-report-eng- (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Tattara, G.; Crestanello, P. Industrial Clusters and the Governance of the Global Value Chain: The Romania–Veneto Network in Footwear and Clothing: Regional Studies: Vol 45, No 2. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00343401003596299?casa_token=kkODK1HNgi0AAAAA%3AQoet4oiMri2cVPgPOXVI8Pyh71UmGCmzpjJ7gD1nlqTiYrEPucfX2Dgr9gcySZnuQ_NZtkMimaQD (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Oliveira, L.J.C.; Costa, M.H.; Soares-Filho, B.S.; Coe, M.T. Large-scale expansion of agriculture in Amazonia may be a no-win scenario. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 024021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermann, E.; Oliveira, E.A.D.d.; Contin, D.R.; Delvecchio, G.; Martinez, C.A.; Viciedo, D.O.; Moraes, M.A.d.; Prado, R.D.M.; Costa, K.A.d.P.; Braga, M.R. “Warming and water deficit impact leaf photosynthesis and decrease forage quality and digestibility of a C4 tropical grass.”. Physiol. Plant. 2019, 165, 383–402. [Google Scholar]

- Greenpeace. Slaughtering the Amazon. 2009. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/research/slaughtering-the-amazon/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Smeraldi, R.; May, P. A hora da conta: Pecuária, Amazônia e conjuntura. Amigos da Terra Amazônia Brasileira, 2009, São Paulo. Available online: http://commodityplatform.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/a-hora-da-conta.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Swartz, J. How I Did It: Timberland’s CEO on Standing Up to 65,000 Angry Activists. In Harvard Business Review on Greening Your Business Profitably; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA; pp. 197–2010.

- Forest Trends. Supply Change Initiative. Search Company Commitments. Available online: http://supply-change.org/#company-profiles (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Anonymous; (Cuiaba Mato Grosso Brazil). Personal Communication. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cernansky, R. Is Footwear Funding the Burning of the Amazon? Vogue Business. August 2019. Available online: https://www.voguebusiness.com/companies/amazon-fires-footwear-leather-sustainability? (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Spring, J.; Slattery, G. Corporate Fallout for Brazil Heats up Despite Signs Amazon Fires May Be Slowing. Reuters. August 2019. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-environment/corporate-fallout-for-brazil-heats-up-despite-signs-amazon-fires-may-be-slowing-idUSKCN1VJ1I2 (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Andreoni, M.; Maheshwari, S. Is Brazilian Leather Out of Fashion? H&M Stops Buying Over Amazon Fires. NY Times. September 2019. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/05/world/americas/h-m-leather-brazil-amazon-fires.html (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Butler, R. Companies Sourcing Beef, Leather from China Exposed to Brazil Deforestation Risk, Researchers Say. Mongabay. August 2019. Available online: https://news.mongabay.com/2019/08/companies-sourcing-beef-leather-from-china-exposed-to-brazil-deforestation-risk-researchers-say/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Leather Working Group. Traceability. Available online: https://www.leatherworkinggroup.com/how-we-work/traceability (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Responsible Leather Round Table. About the Responsible Leather Round Table (RLRT). Available online: https://responsibleleather.org/about/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Ministério Público Federal do Brasil. Procuradoria da República no Pará. Auditorias Confirmam e Aprimoram Avanços No Controle da Origem da Carne no Pará. 2018. Available online: http://www.mpf.mp.br/pa/sala-de-imprensa/noticias-pa/auditorias-confirmam-e-aprimoram-avancos-no-controle-da-origem-da-carne-no-para (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Gaworecki, M. Rotten Beef and Illegal Deforestation: Brazil’s Largest Meatpacker Rocked by Scandals. Mongabay. 2017. Available online: https://news.mongabay.com/2017/04/rotten-beef-and-illegal-deforestation-brazils-largest-meatpacker-rocked-by-scandals/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Parra-Bernal, G.; Mello, G. Brazil Police Arrest JBS CEO Batista, Plea Deal in Limbo. Reuters. 2017. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-corruption-jbs-insidertrading/brazil-police-arrest-jbs-ceo-batista-plea-deal-in-limbo-idUSKCN1BO17X (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Ministério Público Federal (MPF) do Brasil. Ações penais—Operação Arquimedes. Available online: http://www.mpf.mp.br/grandes-casos/operacao-arquimedes/atuacao-do-mpf/acoes-penais (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Branford, S.; Borges, T. In Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro’s Government is Gutting Environmental Agencies from the Inside. 2019. Available online: https://psmag.com/environment/brazils-government-is-gutting-environmental-protections-from-the-inside (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Watts, J. Deforestation of Brazilian Amazon Surges to Record High. The Guardian. 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/04/deforestation-of-brazilian-amazon-surges-to-record-high-bolsonaro (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Anonymous. Desmonte sob Bolsonaro Pode Levar Desmatamento da Amazônia a Ponto Irreversível, diz Físico que Estuda Floresta há 35 Anos. Globo Negocios. July 2019. Available online: https://epocanegocios.globo.com/Brasil/noticia/2019/07/desmonte-sob-bolsonaro-pode-levar-desmatamento-da-amazonia-ponto-irreversivel-diz-fisico-que-estuda-floresta-ha-35-anos.html (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Institute of Quality Certification for the Leather Sector (ICEC). Certifications. Made in Italy of Leather Production. 2019. Available online: http://www.icec.it/en/certifications/product-economic-sustainability/made-in-italy-of-leather-production (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Weatherley-Singh, J.; Gupta, A. “Embodied Deforestation” as a New EU Policy Debate to Tackle Tropical Forest Loss: Assessing Implications for REDD+ Performance. Forests 2018, 9, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A Green Deal. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Byerlee, D.; Rueda, X. From Public to Private Standards for Tropical Commodities: A Century of Global Discourse on Land Governance on the Forest Frontier. Forests 2015, 6, 1301–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FERN. Support Solidifies for and EU Due-diligence Regulation. 2019. Available online: https://www.fern.org/news-resources/support-solidifies-for-an-eu-due-diligence-regulation-2052/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Umunay, P.; Lujan, B.; Meyer, C.; Cobián, J. Trifecta of Success for Reducing Commodity-Driven Deforestation: Assessing the Intersection of REDD+ Programs, Jurisdictional Approaches, and Private Sector Commitments. Forests 2018, 9, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Goal 15. Protect, Restore and Promote Sustainable Use of Terrestrial Ecosystems, Sustainably Manage Forests, Combat Desertification, and Halt and Reverse Land Degradation and Halt Biodiversity Loss. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/sustainable-development/goal15_en (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- GreenLife. Three Years of the greenLIFE Project. 2014–2017. Layman’s Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/greenLIFEproject/green-life-laymans-report-en (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Italian Tanners Association (UNIC). L’industria Conciaria Italiana. Available online: http://www.unic.it/conceria-italiana/industria-conciaria-italiana (accessed on 11 February 2020).

| Destination Countries | Sum of 2018—Value Free on Board (FOB) (USD) | Percentage of Grand Total in Value | Sum of 2018—Net Weight (kg) | Percentage of Grand Total in Net Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 22,512,774 | 69.7% | 13,971,345 | 67.6% |

| Italy | 7,343,160 | 22.7% | 5,051,382 | 24.5% |

| Portugal | 784,955 | 2.4% | 389,760 | 1.9% |

| Spain | 567,634 | 1.8% | 356,380 | 1.7% |

| Dominican Republic | 366,945 | 1.1% | 274,263 | 1.3% |

| Vietnam | 239,883 | 0.7% | 143,149 | 0.7% |

| India | 152,777 | 0.5% | 251,092 | 1.2% |

| Hong Kong | 92,658 | 0.3% | 59,790 | 0.3% |

| Japan | 84,640 | 0.3% | 39,100 | 0.2% |

| Thailand | 76,236 | 0.2% | 58,960 | 0.3% |

| Taiwan (Formosa) | 75,948 | 0.2% | 41,520 | 0.2% |

| Estonia | 20,020 | 0.1% | 20,220 | 0.1% |

| Grand total | 32,317,630 | 99.9% | 20,656,961 | 99.9% |

| Destination Countries | 2018—Value FOB (USD) | Percentage of Grand Total in Value | 2018—Net Weight (kg) | Percentage of Grand Total in Net Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 7,781,489 | 48.2% | 485,406 | 27.7% |

| United States | 7,467,209 | 46.3% | 399,080 | 22.8% |

| Netherlands | 7,102.79 | 0.0% | 672,991 | 38.4% |

| Hong Kong | 1,313.82 | 0.0% | 100,340 | 5.7% |

| Italy | 879,505 | 5.4% | 92,325 | 5.3% |

| Canada | 7,906 | 0.0% | 332 | 0.0% |

| Grand total | 16,144,526 | 99.9% | 1,750,474 | 99.9% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mammadova, A.; Masiero, M.; Pettenella, D. Embedded Deforestation: The Case Study of the Brazilian–Italian Bovine Leather Trade. Forests 2020, 11, 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11040472

Mammadova A, Masiero M, Pettenella D. Embedded Deforestation: The Case Study of the Brazilian–Italian Bovine Leather Trade. Forests. 2020; 11(4):472. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11040472

Chicago/Turabian StyleMammadova, Aynur, Mauro Masiero, and Davide Pettenella. 2020. "Embedded Deforestation: The Case Study of the Brazilian–Italian Bovine Leather Trade" Forests 11, no. 4: 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11040472

APA StyleMammadova, A., Masiero, M., & Pettenella, D. (2020). Embedded Deforestation: The Case Study of the Brazilian–Italian Bovine Leather Trade. Forests, 11(4), 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11040472