What Drives Household Deforestation Decisions? Insights from the Ecuadorian Lowland Rainforests

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

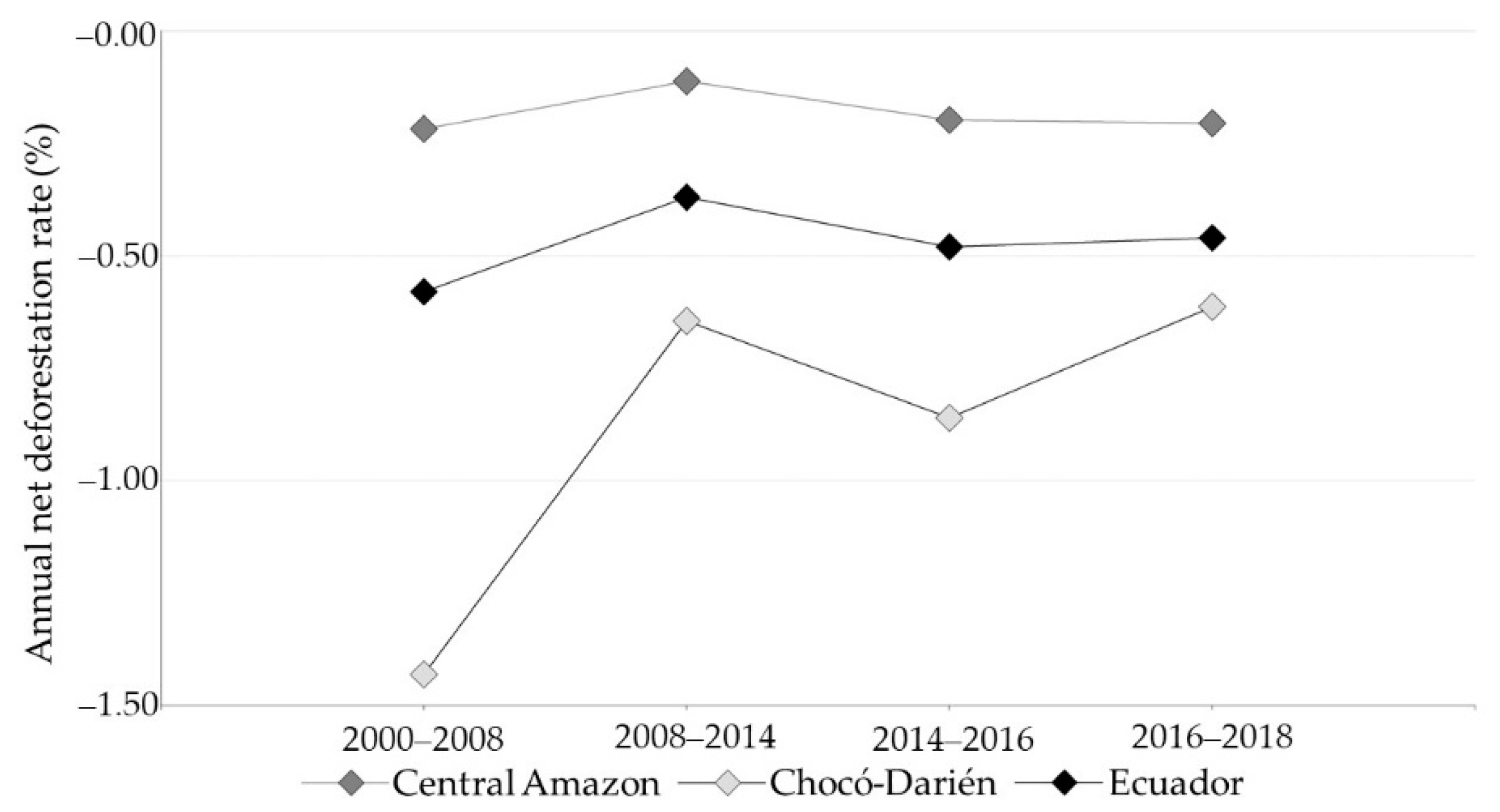

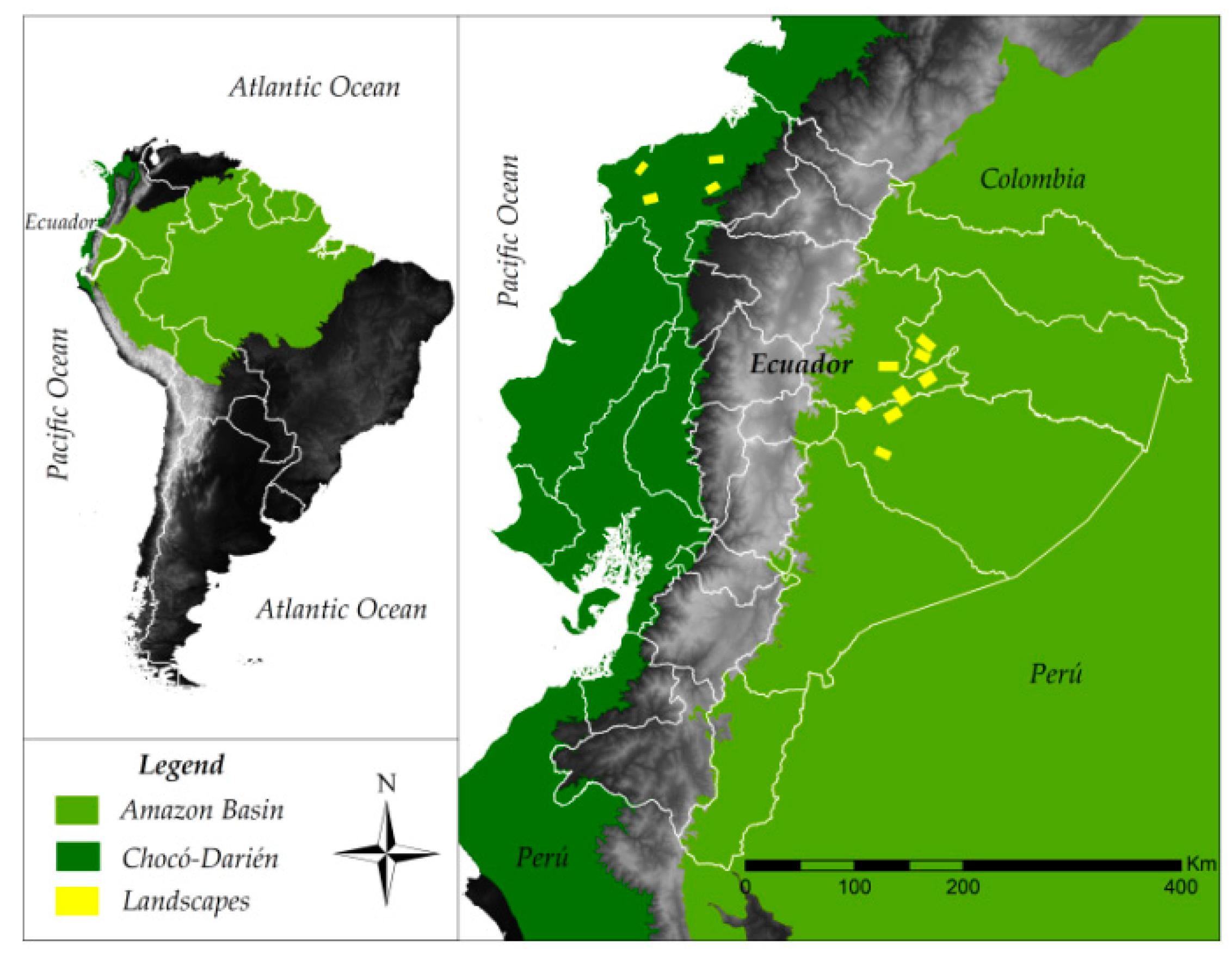

2.1. Study Region

2.2. Sample Selection and Data Collection

2.3. Econometric Model

| Variable | Description | Expected Sign |

|---|---|---|

| Household characteristics | ||

| Age of the head of household | Age in years | Older households are less likely to be physically able to clear forest [33], therefore we expect a negative sign. |

| Indigenous group | 0 = the head of household does not belong to an indigenous group | There are mixed results on this topic. On the one hand, non-indigenous people, “settlers”, have been pointed out as agents of deforestation [34,66]; however, some studies mention that indigenous people can also engage in unsustainable practices when they have access to a market economy [31,91,92]. Overall, we expected a negative correlation between indigenous households and deforestation. |

| 1 = otherwise | ||

| In the Central Amazon, 1 corresponds to Amazonian Kichwa, whereas in the Chocó-Darién, it corresponds to Chachi. | ||

| Education of the head of household | 0 = the head of household completed at least the primary school | More education increases household consumption and production, leading to more deforestation [34]. In addition, educated people have more opportunities to obtain agricultural loans and access markets, promoting agricultural extension [42]. |

| 1 = the head of household has little or no education | ||

| Number of males in working age | Number of males living in the household between 15 and 65 years. | A higher number of adult males living in the household is related with more deforestation [42,43]. |

| Commercialization rate | Percentage of income coming from the sale of agricultural produce. | Commercially oriented households are more likely to deforest to increase their agricultural lands [33]. |

| Credits | 0 = the household received a credit | There are mixed results related to the influence of credits; however, literature indicates that people tend to invest credits into activities that provoke more deforestation [41,77]. |

| 1 = otherwise | ||

| Physical asset index | Comprise physical assets owned by the household (e.g., car, motorbike, bike, telephone, TV, radio, refrigerator). | Asset-rich households tend to clear more forest since they may have more means to develop expansive agriculture [33,42]. |

| Land endowments | ||

| Farm size | 0 = farms with less than 5 ha | Having a smaller farm leads to a more intensive use of the soil, which is translated into more forest clearing [34]. |

| 1 = farms larger than 5 ha | ||

| Forest area within the farm | Percentage of forest area within the farm boundaries prior to the deforestation occurred in the last five years. | A higher proportion of forest area could give the feeling that forest resources are unlimited, motivating people to consume more forest derived products and to convert more forest area into other uses [80]. |

| Quality of forest resources | ||

| Timber volume potential | Average timber volume between old-growth forests and logged forests in m3/ha, which can be legally harvested following the minimum cutting diameter specified in the Ecuadorian forest law for each species [93,94]. Its estimation considers the tree height, diameter at breast height, and a form factor of 0.7, as recommended by Segura et al. [95]. | There is no empirical evidence on the effect of timber potential on deforestation. Our assumption is that the more timber volume available, the more attractive it is for farmers to deforest. |

| Natural resources governance | ||

| Land titling | 0 = the household does not have land titling | Formal tenure is linked with less forest converted to agricultural lands [34,96] |

| 1 = otherwise | ||

| Presence of conservation strategy | In the Central Amazon, four selected sites are influenced by Socio Bosque program (SBP), whereas in the Chocó-Darién, two sites are influenced by a protected area (PA). | On the one hand, strict protection with very few participation of local actors, such as PAs, is reported to be insufficient to disincentive deforestation outside the areas under conservation [86]. Conversely, when protection is accompanied by incentives, such as the SBP, people are more engaged in conservation and have higher environmental awareness [22], suggesting less deforestation in neighboring farms. Despite these mixed results, we hypothesized that households near conservation strategies have lower odds to deforest than those with no conservation strategy in their proximities, implying that the presence of a formal conservation instrument, regardless of whether it is command and control or incentive-based, has the potential to reduce pressure on forests beyond the limits of the areas that are under conservation. |

| 0 = no conservation strategy is present in the landscape | ||

| 1 = otherwise | ||

| Governmental grants | 0 = no household member receives a cash transfer | Governmental grants tend to relax the constrained budget of poor people, reducing the need to deforest [39]. |

| 1 = at least one person in the house is benefited | ||

| Infrastructure | ||

| Distance to the forest | Distance in km from the house to the forest plot owned by the household. | Spatial assessments show that more deforestation occurs when forests are close to the house [13]. Our assumption is that higher distances relate to less deforestation. |

| Distance to market | Distance from the house to the main market in km. | Higher distance to markets reduces the likelihood to deforest [41,43]. |

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keenan, R.J.; Reams, G.A.; Achard, F.; de Freitas, J.V.; Grainger, A.; Lindquist, E. Dynamics of global forest area: Results from the FAO Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 352, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020—Key Findings; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchese, C. Biodiversity hotspots: A shortcut for a more complicated concept. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2015, 3, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basthlott, W.; Hostert, A.; Kier, G.; Kuper, W.; Kreft, J.; Rafiqpoor, D.; Sommer, H. Geographic patterns of vascular plant divesity at continental to global scales. Erdkunde 2007, 61, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. Chapter 5: Saving forests at risk. In WWF Living Forests Report; Taylor, R., Ed.; World Wide Fund for Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- SUIA. Deforestación y Regeneración a Nivel Provincial del Período 2016–2018 del Ecuador Continental. Mapa Interactivo Ambiental. Sistema Único de Indicadores Ambientales; Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MAE; FAO. Resultados de la Evaluación Nacional Forestal; Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador—Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura: Quito, Ecuador, 2014; p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- Sy, V.D.; Herold, M.; Achard, F.; Beuchle, R.; Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Lindquist, E.; Verchot, L. Land use patterns and related carbon losses following deforestation in South America. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 124004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Sierra, R.; Calva, O.; Camacho, J.; López, F. Zonas de Procesos Homogéneos de Deforestación del Ecuador; Factores Promotores y Tendencias al 2020; Programa GESOREN-GIZ y Ministerio de Ambiente del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2013; p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserstrom, R.; Southgate, D. Deforestation, agrarian reform and oil development in Ecuador, 1964-1994. Nat. Res. 2013, 4, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, R. Patrones y Factores de Deforestación en el Ecuador Continental, 1990–2010. Y un acercamiento a los próximos 10 años.; Conservación Internacional Ecuador y Forest Trends.: Quito, Ecuador, 2013; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- MAE. Deforestación del Ecuador Continental Periodo 2014–2016; Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2017; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- MAE. Línea Base de Deforestación del Ecuador Continental; Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2012; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Fagua, J.C.; Baggio, J.A.; Ramsey, R.D. Drivers of forest cover changes in the Chocó-Darien Global Ecoregion of South America. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, J.; Peres, C.A.; Amano, T.; Llactayo, W.; Leader-Williams, N. Conservation performance of different conservation governance regimes in the Peruvian Amazon. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chape, S.; Harrison, J.; Spalding, M.; Lysenko, I. Measuring the extent and effectiveness of protected areas as an indicator for meeting global biodiversity targets. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 2005, 360, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, T.; Ostrom, E. Conserving the world’s forests: Are protected areas the only way? Indiana Law Rev. 2005, 38, 594–617. [Google Scholar]

- MAE. Estrategia Nacional de Biodiversidad 2015–2030; Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2016; p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- MAE. Natural Heritage Statistics of Continental Ecuador; Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2018; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- de Koning, F.; Aguiñaga, M.; Bravo, M.; Chiu, M.; Lascano, M.; Lozada, T.; Suarez, L. Bridging the gap between forest conservation and poverty alleviation: The Ecuadorian Socio Bosque program. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Holland, M.; Naughton-Treves, L.; Morales, M.; Suarez, L.; Keenan, K. Forest conservation incentives and deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Environ. Conserv. 2016, 44, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Programa Socio Bosque. Resultados de Socio Bosque. Resumen General Proyecto Socio Bosque. 2018. Available online: http://sociobosque.ambiente.gob.ec/?q=node/44 (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- FAO; UNEP. The State of the World’s Forests 2020—Forests, Biodiversity and People; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Añazco, M.; Morales, M.; Palacios, W.; Vega, E.; Cuesta, A.L. Sector Forestal Ecuatoriano: Propuestas Para una Gestión Forestal Sostenible; Programa Regional Ecobona-Intercooperation: Quito, Ecuador, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, E.B.; Burgess, J.C. The economics of tropical deforestation. J. Econ. Surv. 2001, 15, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, R.; Stallings, J. The Dynamics and Social Organization of Tropical Deforestation in Northwest Ecuador, 1983-1995. Hum. Ecol. 1998, 26, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, P.; Mejía, E.; Cano, W.; De Jong, W. Smallholder Forestry in the Western Amazon: Outcomes from Forest Reforms and Emerging Policy Perspectives. Forests 2016, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S.J.; Messina, J.P.; Mena, C.F.; Malanson, G.P.; Page, P.H. Complexity theory, spatial simulation models, and land use dynamics in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon. Geoforum 2008, 39, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southgate, D.; Sierra, R.; Brown, L. The causes of tropical deforestation in Ecuador: A statistical analysis. World Dev. 1991, 19, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, C.; Bilsborrow, R.; Torres, B.; Griess, V. Agricultural land use among mestizo colonist and indigenous populations: Contrasting patterns in the Amazon. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, M.; Walker, R.; Eugenio, A.; Stephen, P.; Stephen, A.; Simmons, C. Theorizing land cover and land use change: The peasant economy of Amazonian deforestation. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2007, 97, 86–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babigumira, R.; Angelsen, A.; Buis, M.; Bauch, S.; Sunderland, T.; Wunder, S. Forest clearing in rural livelihoods: Household-level global-comparative evidence. World Dev. 2014, 64, S67–S79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichón, F.J. Colonist land-allocation decisions, land use, and deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon frontier. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1997, 45, 707–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.L. Farm households and land use in a core conservation zone of the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Guatemala. Hum. Ecol. 2008, 36, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, M.; Walker, R.; Perz, S. Small producer deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: Integrating household structure and economic circumstance in behavioral explanation. In CID Working Papers 96; Center for Iinternationa Development at Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, R.; O’Neill, K.; Groff, S.; Kostishack, P.; Cubas, A.; Demmer, J.; McSweeney, K.; Overman, J.; Wilkie, D.; Brokaw, N.; et al. Household determinants of deforestation by Amerindians in Honduras. World Dev. 1997, 25, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettig, E.; Lay, J.; Sipangule, K. Drivers of households’ land-use decisions: A critical review of micro-level studies in tropical regions. Land 2016, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, P.J.; Simorangkir, R. Conditional cash transfers to alleviate poverty also reduced deforestation in Indonesia. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, S.; Sierra, R.; Tirado, M. Tropical deforestation in the Ecuadorian Chocó: Logging practices and socio-spatial relationships. Geogr. Bull. 2010, 51, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Angelsen, A.; Kaimowitz, D. Rethinking the causes of deforestation: Lessons from economic models. World Bank Res. Obs. 1999, 14, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, C.F.; Bilsborrow, R.E.; McClain, M.E. Socioeconomic drivers of deforestation in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon. Environ. Manag. 2006, 37, 802–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.; Carr, D.; Barbieri, A.; Bilsborrow, R.; Suchindran, C. Forest clearing in the Ecuadorian Amazon: A study of patterns over space and time. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2007, 26, 635–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichón, F.J. The forest conversion process: A discussion of the sustainability of predominant land uses associated with frontier expansion in the Amazon. Agric. Hum. Values 1996, 13, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichón, F.J. Settler households and land-use patterns in the Amazon frontier: Farm-level evidence from Ecuador. World Dev. 1997, 25, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacic, Z.; Viteri Salazar, O. The lose-lose predicament of deforestation through subsistence farming: Unpacking agricultural expansion in the Ecuadorian Amazon. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 51, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimowitz, D.; Angelsen, A. Economic Models of Tropical Deforestation. A Review; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 1998; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimowitz, D. The prospects for reduced emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD) in Mesoamerica. Int. For. Rev. 2008, 10, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguiguren, P.; Fischer, R.; Günter, S. Degradation of ecosystem services and deforestation in landscapes with and without incentive-based forest conservation in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Forests 2019, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, A.H. Species richness and floristic composition of Chocó region plant communities. Caldasia 1986, 15, 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Eguiguren, P.; Ojeda Luna, T.; Torres, B.; Lippe, M.; Günter, S. Ecosystem Service Multifunctionality: Decline and Recovery Pathways in the Amazon and Chocó Lowland Rainforests. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, X. Potential Variation in opportunity cost estimates for REDD+ and its causes. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 95, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, H.J.; Lambin, E.F. Proximate Causes and Underlying Driving Forces of Tropical Deforestation. BioScience 2002, 52, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelsen, A.; Rudel, T.K. Designing and implementing effective REDD+ policies: A forest transition approach. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2013, 7, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. State of the World’s Forests; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- SUIA. Cobertura y uso de la Tierra 2018. Mapa Interactivo Ambiental. Sistema Nacional de Monitoreo del Patrimonio Natural. Sistema Único de Indicadores Ambientales; Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, F.L.; Bilsborrow, R.E. Demography, Household Economics, and Land and Resource Use of Five Indigenous Populations in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon: A Summary of Ethnographic Research; University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda Luna, T.; Zhunusova, E.; Günter, S.; Dieter, M. Measuring forest and agricultural income in the Ecuadorian lowland rainforest frontiers: Do deforestation and conservation strategies matter? For. Policy Econ. 2020, 111, 102034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIES. Bono de Desarrollo Humano. Available online: https://www.inclusion.gob.ec/objetivos-bdh/ (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Mena, C.F.; Walsh, S.J.; Frizzelle, B.G.; Xiaozheng, Y.; Malanson, G.P. Land use change on household farms in the Ecuadorian Amazon: Design and implementation of an agent-based model. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, C.L.; Bozigar, M.; Bilsborrow, R.E. Declining use of wild resources by indigenous peoples of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 182, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, M.B.; de Koning, F.; Morales, M.; Naughton-Treves, L.; Robinson, B.E.; Suárez, L. Complex Tenure and Deforestation: Implications for Conservation Incentives in the Ecuadorian Amazon. World Dev. 2014, 55, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, A.F.; Carr, D.L. Gender-specific out-migration, deforestation and urbanization in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2005, 47, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainville, N.; Webb, J.; Lucotte, M.; Davidson, R.; Betancourt, O.; Cueva, E.; Mergler, D. Decrease of soil fertility and release of mercury following deforestation in the Andean Amazon, Napo River Valley, Ecuador. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 368, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, E.; Pacheco, P.; Muzo, A.; Torres, B. Smallholders and timber extraction in the Ecuadorian Amazon: Amidst market opportunities and regulatory constraints. Int. For. Rev. 2015, 17, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquette, C.M. Land use patterns among small farmer settlers in the Northeastern Ecuadorian Amazon. Hum. Ecol. 1998, 26, 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.L. Colonist farm income, off-farm work, cattle, differentiation in Ecuador’s Northern Amazon. Hum. Organ. 2001, 60, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.; Squire, L.; Strauss, J. Agricultural Household Models: Extensions, Applications, and Policy; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Shively, G.; Pagiola, S. Agricultural intensification, local labor markets, and deforestation in the Philippines. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2004, 9, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F. Peasant Economics. Farm Households and Agrarian Development, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Maertens, M.; Zeller, M.; Birner, R. Sustainable agricultural intensification in forest frontier areas. Agric. Econ. 2006, 34, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, C.; Geoghegan, J. Modeling the determinants of semi-subsistent and commercial land uses in an agricultural frontier of Southern Mexico: A switching regression approach. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2004, 27, 326–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviglia-Harris, J.L. Household production and forest clearing: The role of farming in the development of the Amazon. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2004, 9, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sills, E.O.; Lele, S.; Holmes, T.P.; Pattanayak, S.K. Nontimber forest products in the rural household economy. In Forests in a Market Economy; Sills, E.O., Abt, K.L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2003; pp. 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Perz, S.; Caldas, M.; Silva, L.G.T. Land use and land cover change in forest frontiers: The role of household life cycles. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2002, 25, 169–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondizio, E.S.; Cak, A.; Caldas, M.M.; Mena, C.; Bilsborrow, R.; Futemma, C.T.; Ludewigs, T.; Moran, E.F.; Batistella, M. Small farmers and deforestation in Amazonia. In Amazonia and Global Change; Keller, M., Bustamante, M., Gash, J., Silva Dias, P., Eds.; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Volume 186. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.; Moran, E.; Anselin, L. Deforestation and cattle ranching in the Brazilian Amazon: External capital and household processes. World Dev. 2000, 28, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimowitz, D. Forest law enforcement and rural livelihoods. Int. For. Rev. 2003, 5, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D. Basic Econometrics, 4th ed.; The McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Culas, R.J. Deforestation and the environmental Kuznets curve: An institutional perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 61, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börner, J.; West, T.A.P.; Blackman, A.; Miteva, D.A.; Sims, K.R.E.; Wunder, S. National and subnational forest conservation policies: What works, what doesn’t. In Transforming REDD+: Lessons and New Directions; Angelsen, A., Martius, C., De Sy, V., Duchelle, A.E., Larson, A.M., Pham, T.T., Eds.; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2018; pp. 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, A.; Robalino, J.; Lima, E.; Sandoval, C.; Herrera, L.D. Governance, location and avoided deforestation from protected areas: Greater restrictions can have lower impact, due to differences in location. World Dev. 2014, 55, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, P.J.; Hanauer, M.M.; Sims, K.R.E. Conditions associated with protected area success in conservation and poverty reduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 13913–13918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P.; Rueda, X.; Blackman, A.; Börner, J.; Cerutti, P.O.; Dietsch, T.; Jungmann, L.; Lamarque, P.; Lister, J.; et al. Effectiveness and synergies of policy instruments for land use governance in tropical regions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Arsel, M.; Pellegrini, L.; Adaman, F.; Aguilar, B.; Agarwal, B.; Corbera, E.; Ezzine de Blas, D.; Farley, J.; Froger, G.; et al. Payments for ecosystem services and the fatal attraction of win-win solutions. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 6, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFries, R.; Hansen, A.; Turner, B.L.; Reid, R.; Liu, J. Land use change around protected areas: Management to balance human needs and ecological function. Ecol. Appl. 2007, 17, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.J.; DeFries, R. Ecological mechanisms linking protected areas to surrounding lands. Ecol. Appl. 2007, 17, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.K.Y.; Bilsborrow, R.E. The use of a multilevel statistical model to analyze factors influencing land use: A study of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2005, 47, 232–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderlin, W.D.; Dewi, S.; Puntodewo, A. Poverty and Forests: Multi-Country Analysis of Spatial Association and Proposed Policy Solutions; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 5th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; p. 900. [Google Scholar]

- Vasco, C.; Torres, B.; Pacheco, P.; Griess, V. The socioeconomic determinants of legal and illegal smallholder logging: Evidence from the Ecuadorian Amazon. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 78, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, R. Traditional resource-use systems and tropical deforestation in a multi-ethnic region in North-West Ecuador. Environ. Conserv. 1999, 26, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAE. Las Normas para el Manejo Forestal Sostenible de los Bosques Húmedo. Acuerdo, N. 0125; Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MAE. Procedimientos para Autorizar el Aprovechamiento y Corta de Madera. Acuerdo Ministerial 139; Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2010; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Segura, D.; Jiménez, D.; Iglesias, J.; Sola, A.; Chinchero, M.; Casanoves, F.; Chacón, M.; Cifuentes, M.; Torres, R. Part I National Forest Inventories Reports. Chapter 18: Ecuador. In National Forest Inventories: Assessment of Wood Availability and Use; Vidal, C., Alberdi, I.A., Hernández Mateo, L., Redmond, J.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, M.B.; Jones, K.W.; Naughton-Treves, L.; Freire, J.-L.; Morales, M.; Suárez, L. Titling land to conserve forests: The case of Cuyabeno Reserve in Ecuador. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 44, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITTO. Tropical Forest Tenure Assessment; Rights and Resource Initiative and International Tropical Timber Organization: Washington, DC, USA; Yokohama, Japan, 2011; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Bertzky, M.; Ravilious, C.; Araujo Navas, A.L.; Kapos, V.; Carrión, D.; Chíu, M.; Dickson, B. Carbon, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Exploring Co-Benefits. Ecuador; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Código Orgánico Ambiental; Asamblea Nacional de la República del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2017.

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Sexton, J.O.; Austin, M.P.; Collins, C.D.; et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, C.; Ramirez, A.; Marín, H.; Torres, B.; Alemán, R.; Torres, R.; Navarrete, H.; Changoluisa, D. Factores asociados a la fertilidad del suelo en diferentes usos de la tierra en la Región Amazónica Ecuatoriana. Rev. Electrón. Vet. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Mejia, E.; Pacheco, P. Forest Use and Timber Markets in the Ecuadorian Amazon; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2014; p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- Sist, P.; Ferreira, F.N. Sustainability of reduced-impact logging in the Eastern Amazon. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 243, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, W.; Jaramillo, N. Árboles amenazados del Chocó ecuatoriano. Av. Cienc. Ing. 2016, 8, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter-Bolland, L.; Ellis, E.; Guariguata, M.; Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Negrete-Yankelevich, S.; Reyes-García, V. Community managed forests and forest protected areas: An assessment of their conservation effectiveness across the tropics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 268, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendra, H. Do Parks Work? Impact of Protected Areas on Land Cover Clearing. AMBIO 2008, 37, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFries, R.; Hansen, A.; Newton, A.C.; Hansen, M.C. Increasing isolation of protected areas in tropical forests over the past twenty years. Ecol. Appl. 2005, 15, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, P.; Robalino, J.; Arriagada, R.; Echeverría, C. Are government incentives effective for avoided deforestation in the tropical Andean forest? PLoS ONE 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaff, A.; Robalino, J.; Sanchez-Azofeifa, A. Payments for Environmental Services: Empirical analysis for Costa Rica; Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy, Duke University: Durham, NC, USA, 2008; pp. 404–424. [Google Scholar]

- Armenteras, D.; Rodríguez, N.; Retana, J. Are conservation strategies effective in avoiding the deforestation of the Colombian Guyana Shield? Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebalian, P.; Aguilar, F. Beneath the Canopy: Tropical Forests Enrolled in Conservation Payments Reveal Evidence of Less Degradation. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.W.; Etchart, N.; Holland, M.; Naughton-Treves, L.; Arriagada, R. The impact of paying for forest conservation on perceived tenure security in Ecuador. Conserv. Lett. 2020, 13, e12710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, T.; Collen, W.; Nicholas, K.A. Evaluating safeguards in a conservation incentive program: Participation, consent, and benefit sharing in indigenous communities of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, R.; Gerkey, D.; Hole, D.; Pfaff, A.; Ellis, A.M.; Golden, C.D.; Herrera, D.; Johnson, K.; Mulligan, M.; Ricketts, T.H.; et al. Evaluating the impacts of protected areas on human well-being across the developing world. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, A.; Corral, L.; Lima, E.S.; Asner, G.P. Titling indigenous communities protects forests in the Peruvian Amazon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4123–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E.; Holland, M.B.; Naughton-Treves, L. Does secure land tenure save forests? A meta-analysis of the relationship between land tenure and tropical deforestation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 29, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E.; Masuda, Y.J.; Kelly, A.; Holland, M.B.; Bedford, C.; Childress, M.; Fletschner, D.; Game, E.T.; Ginsburg, C.; Hilhorst, T.; et al. Incorporating Land Tenure Security into Conservation. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11, e12383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batallas Minda, P.A. La Deforestación en el Norte de Esmeraldas. Los Actores y sus Prácticas; Editorial Universitaria Abya-Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, E.; Cámara-Leret, R.; Barfod, A.; Weckerle, C.S. Palm use by two Chachi communities in Ecuador: A 30-year reappraisal. Econ. Bot. 2017, 71, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Sellers, S.; Gray, C.; Bilsborrow, R. Indigenous migration dynamics in the Ecuadorian Amazon: A longitudinal and hierarchical analysis. J. Dev. Stud. 2017, 53, 1849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.L.; Bilsborrow, R.E.; Bremner, J.L.; Lu, F. Indigenous land use in the Ecuadorian Amazon: A cross-cultural and multilevel analysis. Hum. Ecol. 2008, 36, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichón, F.J.; Bilsborrow, R.E. Land-use systems, deforestation, and demographic factors in the humid tropics: Farm-level Evidence from Ecuador. In Population and Deforestation in the Humid Tropics; Bilsborrow, R.E., Hogan, D.J., Eds.; International Union for the Scientific Study of Population: Liège, Belgium, 1999; pp. 175–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bilsborrow, R.E.; Barbieri, A.F.; Pan, W. Changes in population and land use over time in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Acta Amazon. 2004, 34, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Central Amazon | Chocó-Darién | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Robust Std. Err. | p | Odds Ratio | Coef. | Robust Std. Err. | p | Odds Ratio | |

| Household characteristics | ||||||||

| Age of the head of household (years) | −0.087 | 0.050 | * | 0.917 | −0.132 | 0.104 | 0.876 | |

| Age squared | 0.001 | 0.000 | 1.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.001 | ||

| Indigenous group (0/1) | −0.055 | 0.415 | 0.946 | 0.874 | 0.344 | ** | 2.397 | |

| Education of the head of household (0/1) | −0.181 | 0.209 | 0.834 | −1.503 | 0.459 | *** | 0.223 | |

| Number of males in working age | −0.157 | 0.056 | *** | 0.855 | 0.768 | 0.329 | ** | 2.155 |

| Commercialization rate (%) | 0.001 | 0.002 | 1.001 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 1.000 | ||

| Credit (0/1) | 0.467 | 0.301 | 1.595 | 0.838 | 0.446 | * | 2.311 | |

| Physical asset index | 0.289 | 0.359 | 1.335 | −0.040 | 0.605 | 0.960 | ||

| Land endowments | ||||||||

| Farm >5 ha (0/1) | −2.225 | 0.358 | *** | 0.108 | −1.809 | 0.060 | *** | 0.164 |

| Forest area within the farm (%) | 0.043 | 0.006 | *** | 1.044 | 0.045 | 0.021 | ** | 1.046 |

| Quality of forest resources | ||||||||

| Timber volume potential (m3/ha) | 0.009 | 0.002 | *** | 1.009 | −0.048 | 0.016 | *** | 0.953 |

| Institutional environment | ||||||||

| Conservation strategy 1 (0/1) | −0.810 | 0.271 | *** | 0.445 | 2.294 | 0.620 | *** | 9.918 |

| Land titling (0/1) | −0.171 | 0.486 | 0.843 | −2.150 | 0.762 | *** | 0.117 | |

| Governmental grants (0/1) | −0.985 | 0.297 | *** | 0.373 | −1.420 | 0.307 | *** | 0.242 |

| Infrastructure | ||||||||

| ln distance to the forest patch (km) | −0.200 | 0.078 | ** | 0.819 | 0.317 | 0.105 | *** | 1.373 |

| ln distance to market (km) | 0.093 | 0.111 | 1.098 | −0.307 | 0.193 | 0.735 | ||

| Intercept | −1.075 | 1.420 | 5.609 | 3.371 | ||||

| Number of observations | 486 | 215 | ||||||

| Hosmer Lemeshow goodness of fit | ||||||||

| x2 | 7.83 | 9.43 | ||||||

| p | 0.45 | 0.31 | ||||||

| VIF | 1.29 | 1.36 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ojeda Luna, T.; Eguiguren, P.; Günter, S.; Torres, B.; Dieter, M. What Drives Household Deforestation Decisions? Insights from the Ecuadorian Lowland Rainforests. Forests 2020, 11, 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11111131

Ojeda Luna T, Eguiguren P, Günter S, Torres B, Dieter M. What Drives Household Deforestation Decisions? Insights from the Ecuadorian Lowland Rainforests. Forests. 2020; 11(11):1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11111131

Chicago/Turabian StyleOjeda Luna, Tatiana, Paúl Eguiguren, Sven Günter, Bolier Torres, and Matthias Dieter. 2020. "What Drives Household Deforestation Decisions? Insights from the Ecuadorian Lowland Rainforests" Forests 11, no. 11: 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11111131

APA StyleOjeda Luna, T., Eguiguren, P., Günter, S., Torres, B., & Dieter, M. (2020). What Drives Household Deforestation Decisions? Insights from the Ecuadorian Lowland Rainforests. Forests, 11(11), 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11111131