Abstract

Elevational and polar treelines have been studied for more than two centuries. The aim of the present article is to highlight in retrospect the scope of treeline research, scientific approaches and hypotheses on treeline causation, its spatial structures and temporal change. Systematic treeline research dates back to the end of the 19th century. The abundance of global, regional, and local studies has provided a complex picture of the great variety and heterogeneity of both altitudinal and polar treelines. Modern treeline research started in the 1930s, with experimental field and laboratory studies on the trees’ physiological response to the treeline environment. During the following decades, researchers’ interest increasingly focused on the altitudinal and polar treeline dynamics to climate warming since the Little Ice Age. Since the 1970s interest in treeline dynamics again increased and has considerably intensified from the 1990s to today. At the same time, remote sensing techniques and GIS application have essentially supported previous analyses of treeline spatial patterns and temporal variation. Simultaneously, the modelling of treeline has been rapidly increasing, often related to the current treeline shift and and its implications for biodiversity, and the ecosystem function and services of high-elevation forests. It appears, that many seemingly ‘new ideas’ already originated many decades ago and just confirm what has been known for a long time. Suggestions for further research are outlined.

1. Introduction

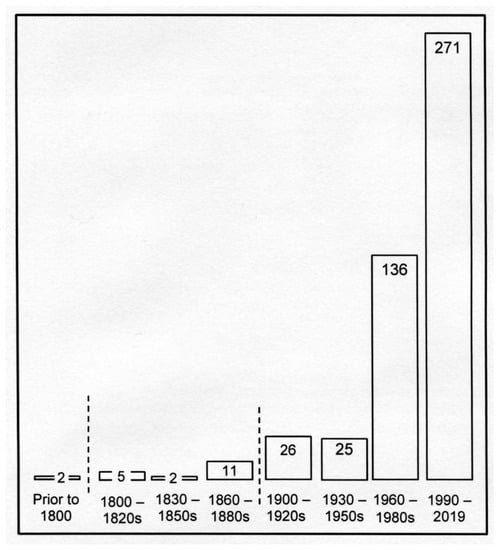

Elevational and polar treelines, the most conspicuous vegetation boundaries in high mountains and in the Subarctic, have attracted researchers from numerous disciplines. Thus, scientific approaches to treeline have become increasingly complex. Treeline research dates back to more than two centuries. Since the end of the 20th century, treeline publications have been rapidly increasing. Nearly 60% of the articles and books from the 1930s onward were published during the two last decades. Older contributions have gradually become disregarded in recent articles, or have been cited from secondary sources. The objective of the present article is to highlight in retrospect the scope of treeline research, scientific approaches and hypotheses on treeline causation, and its spatial and temporal structures.

The cited references can only represent a very small selection of an abundance of relevant publications. This also means, that we could not cover all topics in treeline research. Anthropogenic pressure (pastoralism, use of fire, mining, etc.), for example, is only randomly considered, although it has controlled treeline position and spatial pattern in the inhabited world for thousands of years, often overruling the influence of climate. Moreover, the multiple influences of wild animals, pathogens, and diseases have not been concentrated on, as the species’ distribution, populations and kinds of impact vary locally and regionally. Extensive reviews on this particular topic and the anthropogenic impact were presented by [1,2,3,4].

Early publications were usually descriptive, and the results were not tested statistically. Anyway, going ‘back to the roots’, the reader will soon realize that many ‘new ideas’ seemingly representing the actual ‘frontline’ of treeline research originated many decades ago and just confirm what has been known for a long time such as the fundamental functional role of heat deficiency in treeline control [5,6], or the advantage of short plant tree stature in high mountain and subarctic/arctic environments (e.g., [7,8]).

2. Scope and Topics of Treeline Research

2.1. Early Treeline Research

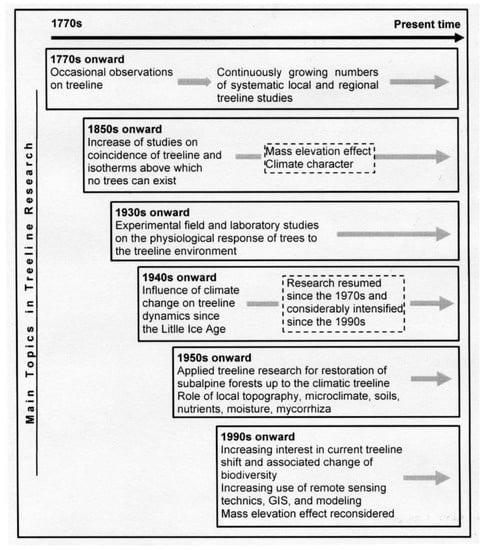

Early treeline research started around the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 20th century. In the beginning, treeline research was closely linked with the exploration of high-mountains and the northern forest-tundra. There were occasional and more general observations, including the physiognomy and distribution of vegetation and hypotheses on the influence of climate on treeline (e.g., [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scope and main topics of treeline research in the course of time.

Systematic research dates back to the end of the 19th century/beginning of the 20th century [5,7,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] (Figure 1). Coincidence of treeline position and certain isotherms of mean growing season temperatures became apparent which clearly reflected the influence of heat deficiency. Gannet’s article on timberline [38] is regarded as the beginning of systematic treeline research in North America [39]. Later, Griggs [40] published an overview on North American treeline which was followed by a more popularized introduction to timberlines by Arno [41]. This book is focused on North America but also gives a short worldwide view.

Early researchers ([2] for review, [22,27,33,34,35,42,43]) already pointed to the treeline raising mass-elevation effect (MEE). Brockmann-Jerosch [33] found MEE often overlapping with the positive influence of the relatively continental climate character in the central parts of big mountain masses (see also [34]). There, the combined effects of greater daily thermal amplitude associated with high elevation, high solar radiation loads, reduced cloudiness, and lower precipitation, resulting in warmer topsoils and microclimate near the ground allow treeline trees to exist at a lower mean growing season air temperature (or annual temperature in the tropics) than in the outer low ranges exposed to moisture-carrying air masses and on isolated mountains (‘summit phenomenon’, sensu [44]). The mechanism of MEE has been approached again in numerous studies largely confirming the previous hypotheses ([2] for literature until 2005). During the last 14 years the discussion on the MEE came up again (e.g., [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]).

Growth forms of trees were found to be indicators of the harsh treeline environment. Dwarfed growth of trees, for example, and wide-spacing of trees in treeline ecotones had already been described in detail by early researchers as a characteristic of the climatic treeline (e.g., [7,21]). They considered ‘mats’ and similar low growth forms as ‘trees’ suppressed by recurrent winter injury (desiccation, frost, abrasion) above the protective winter snowpack. The beneficial effect of the relatively warmer conditions (growing season) near the ground surface was also well known (see also e.g., [5,7,8]) and studied later in detail [53].

2.2. Modern Treeline Research

Modern treeline research began in the 1930s, with emphasis on the trees’ physiological response to the harsh treeline environment (Figure 1). A biological study by Däniker [54] on treeline causation in the Alps, with special regard to the influence of climate and tree anatomy, had already opened perspectives for future research. Experimental studies in the field and laboratory became of major importance (e.g., [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]). During World War II (1939–1945), the number of publications on treeline at the regional scale considerably decreased, especially in Eurasia, where the political situation made field studies very difficult or even impossible. Nevertheless, a few articles also date from this period [66,67,68,69,70,71].

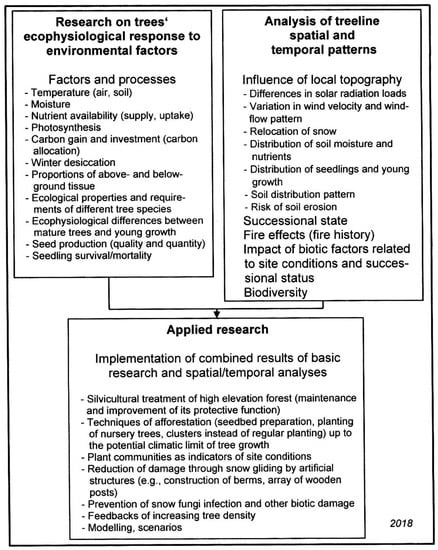

Disastrous avalanche catastrophes in the European Alps during the extremely snow-rich winters 1951/1952 and 1953/1954 gave a fresh impetus to basic and applied treeline research. In Austria and Switzerland, basic research on the physiological reponse of treeline trees to their environment combined with the analyses of the functional role of the most relevant site factors and processes created scientific basics for high-elevation forest management and maintenance, including afforestation up to the potential tree limit (e.g., [72,73,74]) (Figure 2). For practical use in high-altitude afforestation in the central Alps ecograms were developed [75,76] showing a schematic transect from convex to concave microtopography with the distribution of the characteristic plant communities as indicators of the site conditions varying along the transect see also [1,77].

Figure 2.

Fundamentals of treeline research and practical implementation.

2.2.1. Carbon

Limited carbon gain due to low temperature and a short growing season, has long been considered the main ecophysiological cause of climatic treeline (e.g., [78,79]), the inhibition of carbon investment gained importance (e.g., [80,81,82]). Increasing CO2 in the atmosphere and associated ecophysiological effects on the treeline environments and trees has again stimulated research on carbon dynamics during the last three decades (e.g., [83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98]).

2.2.2. Winter Desiccation

Winter desiccation (WD) is an additional recurrent topic. It was already considered by early researchers as the bottleneck in the performance of young trees at the alpine and polar treelines (e.g., [7,99,100,101,102]), where WD had been observed mainly on strongly wind-swept local topography (see also [103]). WD was blamed for the high cuticular transpiration loss through immature needle foliage with both frozen soil and the conductive tissue preventing water uptake (e.g., [56,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120]). This plausible ‘mechanism’ has been readily accepted as a key factor in treeline causation in biology, forestry, and geography textbooks (e.g., [121,122,123]). Although reduced cuticle thickness and cuticular water loss are common at the treeline in winter-cold mountains, they are not necessarily associated with lethal damage (e.g., [124,125,126]). If needles and shoots are not killed, they may rapidly rehydrate in the following spring [127,128]. It appears that on extremely windy terrain mechanical injuries (e.g., abrasion by blowing snow/ice and sand, breakage of frozen needles, and shoots) can increase the susceptibility of needle foliage and shoots to WD (e.g., [129,130,131,132,133] for review). Frequent freeze-thaw events may also be involved, as well as early or late frost (e.g., [63,73,134,135]). On the whole it appears that WD cannot be attributed to insufficient cuticle development alone, and its role in treeline causation needs to be relativized.

In 1979 Tranquillini [103] compiled the results of his own and that of others in an often cited book, which represented the state of knowledge about the physiological ecology of treeline at that time. Wieser and Tausz [136] edited a volume with contributions of 11 experts on the eco-physiology of trees at their upper limits. The main focus of this book is on the European Alps. Five years later, Körner [93] gave a concise overview of the present state of knowledge about the ecophysiological response of trees to the environmental constraints at treeline.

2.2.3. Treeline and Temperature

The relationship between treeline and temperature, well known already to early researchers, has also been in the focus of modern research. As root zone temperatures during the growing season correlate better than more widely fluctuating air temperatures with worldwide treeline position (e.g., [86,137]), they were suggested as the universal factor in treeline causation ([86] onward). The relative effects of soil temperature on trees, and especially on tree seedlings, may considerably vary depending on local site conditions (e.g., available moisture, organic matter, decomposition, nutrients, and the species’ specific requirements). In a worldwide view, the location of the potential climatic treeline has been associated with the length of a growing season of at least 94 d, with a daily minimum temperature of just above freezing (0.9 °C) and a mean of 6.4 °C during this period [138]. This largely corresponds to the previous statement by Ellenberg [121] that the altitudinal position of the climatic treeline is associated with an air temperature exceeding 5 °C for at least 100 days. A critical mean root zone temperature of about 6 °C during the growing season comes close to the critical thermal threshold of 5 °C, when biochemical processes are generally impeded [139,140] and tree growth is interrupted [90].

Although the mean growing season temperature is not identical with a real physical threshold temperature below which no trees can exist (e.g., [141,142]), its relation to treeline position once again supports the well substantiated early finding that heat deficiency is the globally dominating constraint on tree existence at the elevational and polar treelines [143]. Therefore, linking treeline with growing season mean soil or air temperature allows an approximate projection of the future climatic treeline position at broad scales (global, zonal) (e.g., [138,144]).

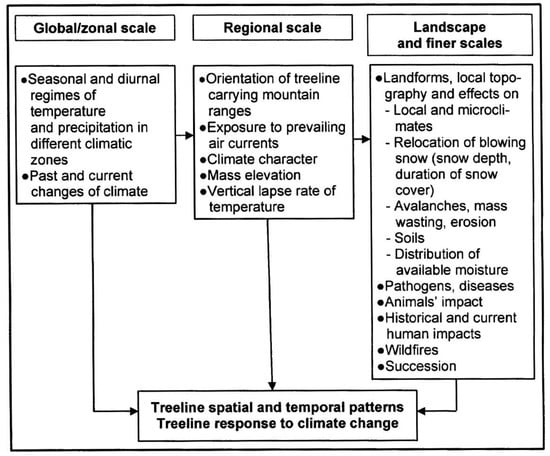

Regional and local variations, however, are more difficult to foresee, as thermal differences may occur on small scales, that are as great in magnitude as those that occur over thousands of kilometers in the lowland [115,145]. Exposure of mountain slopes and microtopography to incident solar radiation and prevailing winds is of major importance in this respect (e.g., [2,115,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159]). These factors and many additional physical and biotic disturbances (e.g., [134,160]) may prevent tree growth from reaching the temperature-controlled climatic treeline projected by models, as for example the model of [138]. In addition, historical displacement of treeline by humans and a delay of treeline response to climate change also play a major role in the respect. Hence, at finer scales, treeline position is often out-of-phase with climate (e.g., [1,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176]). Global overviews, necessarily disregarding the local differences, may easily overemphasize coarse drivers such as temperature [167,177,178].

Overall, the assessment of the underlying possible causes at finer scales will be a great challenge to treeline researchers also in the future (e.g., [179]). Modelling the influence of abiotic factors on the New Zealand treeline [180], for example, showed 82% of treeline variation at regional scale being associated with thermal conditions, whereas only about 50% could be attributed to temperature at finer scales.

2.2.4. Treeline Fluctuations

Treeline fluctuations due to warming and cooling periods after the end of the Little Ice Age and during the 20th century were already considered in numerous studies ([2], for literature). However, it appears that the climatically driven current treeline advance to greater elevation and to northern latitude has even attracted greater attention (Figure 1). During the last three decades, especially since the 1990s, publications on this topic have rapidly increased (by about 90%), partly in a broader context with the change of vegetation and biodiversity, and the expected implications for the ecosystem functions and services of high-elevation forests (e.g., [88,134,167,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205]) (Figure 3). Dendrochronology, pollen analysis, sediment analysis, and radiocarbon-dating of fossil wood remains (mega fossils) have provided a profound insight into Holocene treeline fluctuations (e.g., [203,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224]). In not a few cases their after-effects have lastingly influenced the current treeline position and spatial patterns (e.g., [1,2] and references therein).

Figure 3.

Number of treeline-related publications during consecutive 30-years periods, compiled from the reference list of the current article. Note the exorbitant increase since the 1960s and especially since the 1990s, when the number of publications doubled compared to the previous 30 years (1960–1980s).

Treeline studies by geographers, landscape ecologists, foresters, and geobotanists have referred in particular to treeline in the landscape context aiming to explain spatial treeline structures and their development under the influence of multiple, partly interacting abiotic and biotic factors (Figure 2) [225,226,227,228,229]; for more publications prior to 2008 see [2,77,199,230,231,232,233]. In this context, natural and anthropogenic disturbances have been increasingly studied (e.g., [2,3,160,166,177,215,232,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242,243,244,245]). These studies have contributed to the assessment of treeline fluctuations in a more holistic view. As both natural and anthropogenic disturbances are closely linked with a multitude of locally and regionally varying preconditions, a generalization, however, is problematic.

Traditional ground-based repeat photography (e.g., [168,171,203,246,247,248,249,250,251]), remote sensing techniques (oblique air photos, satellite images) and GIS data (e.g., [181,242,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259,260,261,262,263,264,265,266,267,268,269,270]) have effectively supported the analysis of current (and also of historical) treeline spatial patterns and temporal variation such as treeline fluctuations, especially in remote areas and areas difficult to access, such as steep and rugged mountain terrain [270,271]. These studies have also contributed to a more complex view of the driving factors and also underlined that factors and processes vary by scale of consideration (e.g., [159,180,184,205,272,273]) (Figure 4). Thus, in addition to the numerous studies on the physiological response of treeline trees to heat deficiency at the broader scales (global/zonal/regional), the influences of local topography (landforms) on treeline spatial patterns and associated ecological processes have been increasingly studied, particularly in Austria and Switzerland (e.g., [75,274,275,276,277]) (Figure 4). During the last decades, this issue has moved again in the focus of treeline research worldwide (e.g., [147,148,149,156,227,229,278,279,280,281,282,283,284,285,286,287,288,289,290,291,292,293]).

Figure 4.

Combined results of research at different scales explain treeline spatio-temporal response to climate change.

2.2.5. Soils in the Treeline Ecotone and in the Alpine Zone

The need for maintenance and restoration of high elevation protective forests and afforestation above the present subalpine forest has also fuelled research on soils in the treeline ecotone and in the alpine zone (e.g., [139,279,280,294,295,296,297,298,299,300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312]). High-elevation soils have been considered in a worldwide view by a FAO report [313]. In addition, Egli and Poulenard [314] published a review on soils of mountainous landscapes. However, in most treeline studies soils are considered only briefly, with just a few exceptions (e.g., [256,309,310,315]). Based on many treeline studies in the Alps, northern Europe and North America, the present authors have come to the conclusion that no real treeline-specific soil types exist [2,273,316]. Instead, the treeline ecotone is usually characterized by a mosaic of soil types, closely related to the locally varying conditions [256].

2.2.6. Precipitation and Soil Moisture

While heat deficiency has generally been accepted as the main factor in global treeline control, the role of precipitation and related soil moisture supply at treeline has remained less clear. This may be due to the great regional and local variation. During the last two decades, however, the role of precipitation has been increasingly dealt with, mainly in the context with climatically-driven treeline shifts and the growing number of studies on treeline in mountains influenced by seasonal drought. The impacts of heat deficiency and drought often overlap, and drought periods may overrule the positive effects of climate warming [178,257,263,317,318,319,320,321,322,323,324,325,326,327]. A detailed review on the physiological response of trees to drought and new insights in understanding of trees’ hydraulic function in general was recently presented by Choat et al. [328].

While warming climate is often associated with increasing summer drought, moisture carrying warm air currents may bring about increased winter snowfall at high elevation (e.g., Alps, Himalaya, Alaska). There are great variations, however, due to climate regimes, elevation and distance from the oceans. Anyway, when big snow masses accumulate during a few days of extreme synoptic conditions more destructive (wet snow) avalanches are likely [273,329,330,331,332].

Moisture availability is only partly associated with the total amount of precipitation and may considerably vary depending on microtopography, soil physical conditions, and soil organic matter. Moreover, the tolerance of moisture deficiency of tree species differs (e.g., [333]). Seedlings are more sensitive to lack of moisture than deep-rooted mature trees (e.g., [334,335,336,337]) which may be attributed to slow initial growth and great reliance on seed reserves [338].

On several tropical/subtropical islands, drought stress affects trees and seedlings above the trade-wind inversion. There may however be many additional factors involved (e.g., geological and vegetation history, climate variability, human impact, etc.) (e.g., [46,339,340,341,342,343]). Thus, the low position of the treeline on some remote ocean islands has also been ascribed to the absence of hardy tree species which could not reach these islands [110,343].

Growing concern about climatically-driven impact by drought, fire, mass-outbreaks of bark beetle, pathogens, and increasing outdoor activities on high mountain resources has fuelled treeline research, often with emphasis on high-elevation forest management ([344] and literature within). High-elevation forests including treeline ecotones are particularly valuable as wildlife habitats and because of their protective function such as avalanche and erosion control (e.g., [160,345]). Not least they serve as an environmental indicator.

2.2.7. Natural Regeneration

While, in general, response of mature trees to climate warming is in the focus, climate change has also stimulated new research on natural regeneration and its particular role as a driving force in worldwide treeline upward and poleward shifts (see [2] for literature prior to 2008 (e.g., [201,346,347,348,349,350,351,352,353,354,355,356,357,358,359,360,361,362,363,364,365,366]). Publications on regeneration at treeline have increased by more than 60% since the last two decades.

Normally, both seed quantity and quality (viability) decrease when approaching the treeline. Occasionally, however, trees growing even far above the mountain forest produce viable seeds, from which scattered seedlings may emerge at safe sites. As the regeneration process usually extends over several years, it is highly prone to disturbances and may therefore fail at any stage [2,336,367].

It has been and still is being debated, whether the scarcity of viable seeds or paucity of safe sites are more restrictive to tree establishment within and above the current treeline ecotone (e.g., [93,109,168,171,182,186,361,368,369,370,371,372,373,374,375,376,377,378]). Whatsoever, increased production and availability of viable seeds will not necessarily initiate successful seedling recruitment (e.g., [171,182,186,261,367,379,380,381]) Altogether, seed-based regeneration in and above the treeline ecotone depends on the availability of viable seeds, varying locally, and on the distance from the seed sources, suitable seed beds, and multiple disturbances (e.g., [2,3,160,191,261,353,355,361,366,367]). Last but not least, mycorrhization is essential for a successful seedling establishment in and especially above the treeline ecotone, where it is closely related to locally varying site conditions (e.g., [382,383,384,385,386]). It appears, that only trees with ectomycorrhiza are able to exist up to the climatic limit of tree growth [382,387]. In the end, however, effective natural regeneration depends on the hardiness of tree seedlings and whether these will attain full tree size or at least survive as suppressed growth form. Overall, operating with long-term growing season temperature alone does not allow a fairly well assessment of whether seed-based regeneration within the treeline ecotone and in the lower alpine zone will be successful or fail.

As to current treeline dynamics, the role of layering (the formation of adventitious roots) and also of stump sprouts and root suckers, well known already to early researchers (e.g., [7,21,388]), deserves closer attention [389]. Layering still is active at low temperatures which would prevent seed-based regeneration (e.g., [390,391,392]). Clonal groups which developed at high elevation under temporary favourable conditions and survived subsequent cooling (after the Little Ice Age) may now serve as an effective seed source far above the current subalpine forest (e.g., [157]).

2.2.8. Feedbacks of Increasing Tree Population

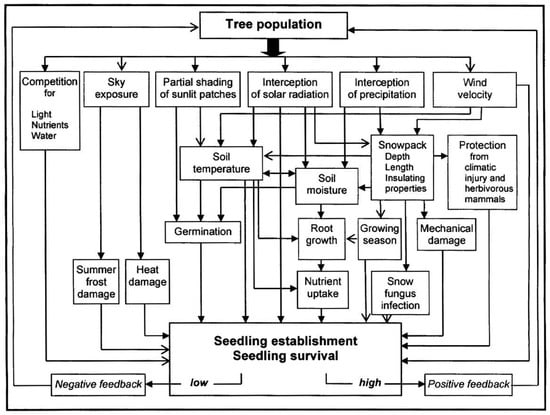

The feedbacks of increasing tree population in the treeline ecotone on their close environment (Figure 5) are being increasingly considered (e.g., [147,148,149,155,157,258,278,393,394]). Increasing stem density may be associated with both positive and negative effects. Thus, trees and clonal groups growing to greater height reduce wind velocity and increase the deposition of blowing snow, which may provide shelter to young growth from climatic injury in winter-cold climates (e.g., [368,395]), while infection of evergreen conifers by parasitic snow fungi increases and can be fatal for seedlings and saplings. The increasing crown cover will reduce growing season soil temperature in the rooting zone and may thus impede root growth. Whatsoever, field studies on the response of Swiss stone pines to low soil temperatures as a result of self-shading have provided evidence that fine roots abundance and dynamics at the treeline is not affected by self-shading [396].

Figure 5.

Feedbacks of increasing tree population on site conditions, seedling erstablishment, and survival (modified from [2]).

It has even been argued that densely grouped trees themselves would reduce their possible lifetime through shading the ground [86], whereas, sunlit patches between wide-spaced trees and tree groups usually exhibit higher daytime soil temperatures during the growing season (e.g., [20,22,23,27,131,147,397,398,399,400,401]), that might facilitate tree establishment. Nevertheless, adverse climatic factors [372,402,403,404] (e.g., recurrent frost damage, precocious dehardening in winter, summer frosts, strong prevailing winds, ice-particle abrasion, and photooxidative stress) can outweigh the advantage of reduced shading between wide-spaced trees (e.g., [2,103,178,359,372,403,405,406,407,408,409,410]).

Moreover, increasing tree density in the treeline ecotone may aggravate the competition for moisture, nutrients, and light between adult trees and juvenile trees (e.g., [157,293,411,412]). Not least, the competition between young trees, dwarf shrub, and ground vegetation may impede the establishment of trees [293,365,401,413,414,415,416,417,418,419]. Competition may even be more important than direct climatic effects, such as the length of the snow-free period, for example [359], or soil temperature. More systematic studies on competition as an ecological factor in the treeline ecotone are needed for a better understanding of treeline spatial and temporal dynamics.

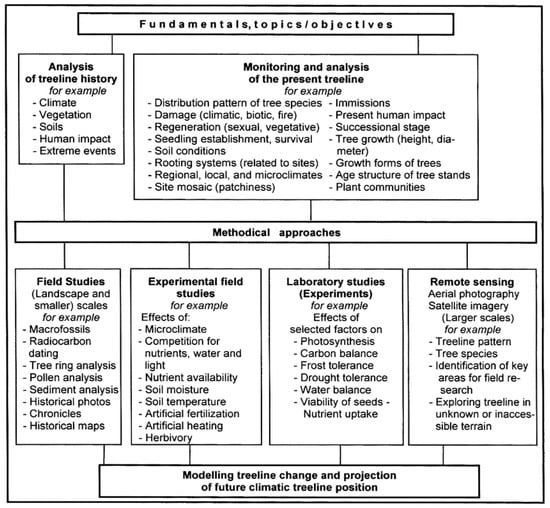

2.2.9. Modelling Treeline and its Environmental Constraints

Since the 1990s, the modelling of treeline and its environmental constraints has rapidly increased. Modelling, in particular when combined with field- and laboratory experiments, allows alternative scenarios of possible treeline response to environmental pressure (Figure 6) (e.g., [87,137,138,145,172,173,258,289,350,365,373,409,420,421,422,423,424,425,426,427,428,429,430,431]). Due to rapidly growing numbers and the great diversity of modelling techniques it may be difficult, however, to find the most appropriate method (e.g., [432,433,434]). To apply the results to other environments proves to be problematic or even impossible as models and scenarios are usually based on local data sets collected within a limited period of time (see also [2,205,433]). Thus, model-based projections of future treeline have often failed. At the treeline of Scots pine in northernmost Europe, for example, climate warming did not seem to be sufficient to compensate abiotic and biotic pressures on treeline trees (e.g., [321]). In addition, in north-central Canada (west of Hudson Bay) the climatically-driven northward advance of treeline as predicted by various models has not yet occurred [326].

Figure 6.

Fundamentals, topics, and objectives of modelling treeline (modified from [2]).

3. Conclusions and Perspectives

This research review, stemming from the roots of early research in the 1700s to modern research beginning in the 1930s, contributes to a multi-facetted view of the treeline (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 4). Although the number of studies per year and the level of complexity has increased over time, many ‘new ideas’ seemingly representing the actual ‘frontline’ of treeline research, originated decades earlier and just confirm what has been known a long time (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Some established hypotheses need to be reassessed, such as global and regional overviews that have often overemphasized coarse drivers such as temperature. A focal point of early treeline research was linking the worldwide treeline position with an empirically found thermal average (mean growing season temperature) seemingly limiting tree growth. Not a few recent treeline studies have still been following the same idea and come to not really ‘new’ insights into trees’ functional response to the treeline environment. Especially during the last two decades, the mass-elevation effect (MEE) was reconsidered in many studies largely confirming the previous hypotheses dating from the early 1900s.

Additional work is needed to decipher the fundamental functional role of heat deficiency in treeline control. The same applies to the role of precipitation (rain, snow) and available soil moisture (dependent on soil texture, humus content, and microtopography) during the growing season in different climatic regions. More research at local and regional scales is required to broaden and corroborate knowledge in this field.

Disastrous avalanche catastrophes during two successive extremely snow-rich winters in the 1950s and current climate warming have become important drivers of modern treeline research. The extremely snow-rich winters in particular stimulated basic and applied treeline research (Figure 2). As afforestation and maintenance of high-elevation protective forests was the main objective, the nature of the entire elevational belt (treeline ecotone) itself was increasingly considered. Finding out which factors prevent trees in many places from reaching its potential climatic limit has been a strong challenge for researchers since then.

Scales of consideration play an important role in treeline research, as treeline heterogeneity, spatial mosaic, and ecological variety increase from coarse (global, zonal) to finer (regional, landscape, micro) scales (Figure 4). Finer scale assessments of the relative importance and function of the treeline-relevant factors and processes (human impact included) are fundamental for better understanding of treeline causation and its possible response to climate (environmental) change.

Research on episodic reproduction and treeline fluctuations in response to climate warming since the end of the Little Ice Age has steadily increased from the 1940s onward (Figure 1). Since the 1990s, the effects of current climate warming on treeline have considerably fuelled treeline research comparable to the effect of the avalanche catastrophes in the Europen Alps during the snow-rich winters in the 1950s.

Changes of biodiversity and structural diversity due to feedbacks of increasing tree population (Figure 5) within the current treeline ecotone and in the adjacent lower alpine zone, as well as the resulting implications for the ecological conditions, also require local studies.

As the impact of climate change and treeline response often overlaps with anthropogenic influences and natural factors, it is suggested that future treeline-related research could benefit from means to successfully disentangle the effects of these factors on treeline position, spatial structures and dynamics.

Remote sensing techniques and GIS have become excellent tools for monitoring treeline spatial patterns and structures at coarse and finer scales, particularly in areas difficult to access. Such innovative research techniques will be needed to come to a better assessment of the multiple and often mutually influencing factors and processes controlling treeline causation, spatial patterns, and dynamics. Thus, they will also promote projection of future treeline position (Figure 6).

In addition to specialized research on the physiological functions and response of trees to the harsh treeline environment, studies based on a more holistic approach may considerably contribute to complete our knowledge on nature of treeline. The results from the different disciplines and experts involved in treeline research must be combined and integrated into the varying spatio-temporal patterns of treelines. In this context, research on the effects of recurrent disturbances, disregarded whether natural or anthropogenic, appear as important as tree physiological research.

Author Contributions

Both authors have contributed to this article at equal parts. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ingrid Lüllau (Ismaing) for revising the English text.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Holtmeier, F.-K. Geoökologische Beobachtungen und Studien an der subarktischen und alpinen Waldgrenze in vergleichender Sicht (nördliches Fennoskandien/Zentralalpen). In Erdwissenschaftliche Forschung; Steiner Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1974; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Holtmeier, F.-K. Mountain Timberlines. Ecology, Patchiness, and Dynamics. In Advances in Global Change Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 36. [Google Scholar]

- Holtmeier, F.-K. Impact of wild herbivorous mammals and birds on the altitudinal and northern treeline ecotones. Landsc. Online 2012, 30, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, R.M.M. Tundra-Taiga Biology. In Human, Plant, and Animal Survival in the Arctic; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wegener, A. Das Wesen der Baumgrenze. Meteorol. Z. 1923, 40, 371–372. [Google Scholar]

- Daubenmire, R. Alpine timberlines in the Americas and their interpretation. Butl. Univ. Bot. Stud. 1954, 11, 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kihlman, A.O. Pflanzenbiologische Studien aus Russisch-Lappland; Weilin & Göös: Helsinki, Finland, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Raunkiaer, C. Types biologiques pour la géographie botanique. Bull. Acad. R. Sci. 1905, 5, 347–437. [Google Scholar]

- Von Haller, A. Historia Stirpium Indigenarum Helvetiae Inchoate; Sumptibus Societas Typographica: Bernae, Switzerland, 1768. [Google Scholar]

- Hacquet, B. Mineral—Bot. Lustreise von dem Berge Terglu Krain zu dem Berge Glockner Tirol. 1779. [Google Scholar]

- Zschokke, H. Beobachtungen im Hochgebirge auf einer Alpenreise im Sommer 1803. In Isis, Wochenschrift von deutschen und schweizerischen Gelehrten; Band I/II: Zürich, Switzerland, 1805. [Google Scholar]

- Von Humboldt, A.; Bonpland, A. Essai sur la géographie des Planters; Chez Levraud, Schoell et Compagnie: Paris, France, 1805. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlenberg, G. Flora lapponica; Berolini: Berlin, Germany, 1812. [Google Scholar]

- Kasthofer, K. Bemerkungen auf einer Alpenreise über den Susten, Gotthard, Bernhardin, und über die Oberalp, Furka und Grimsel; Aarau, Switzerland, 1822. [Google Scholar]

- Kasthofer, K. Bemerkungen auf einer Alpen-Reise über den Brünig, Bragel, Kirenzenberg, die Flüela, den Maloja und Splügen; Bern, Suisse, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Von Middendorf, A.T. Sibirische Reise. Band IV. Teil 1. Übersicht der Natur Nord- und Ost-Sibiriens; Die Gewächse Sibiriens; Vierte Lieferung: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1864. [Google Scholar]

- Sendtner, O. Die Vegetationsverhälnisse Südbayerns; Literarisch-Artistische Anstalt: München, Germany, 1854. [Google Scholar]

- Landolt, E. Bericht an den hohen schweizerischen Bundesrat über die Untersuchung der schweizerischen Hochgebirgswaldungen, vorgenommen in den Jahren 1858, 1959 und 1860; Bern, Switzerland, 1862. [Google Scholar]

- Kerner, A. Studien über die obere Waldgrenze in den österreichischen Alpen. Österreichische Revue, 1894/1895. 2/3.

- Fritzsch, M. Über Höhengrenzen in den Ortler Alpen. In Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen für Erdkunde 2; Wien, Austria, 1894; pp. 105–292. [Google Scholar]

- Roder, K. Die polare Waldgrenze. Ph.D. Thesis, Philosophische Fakultät der Universität Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Imhof, E. Die Waldgrenze in der Schweiz. Gerlands Beiträge zur Geophys. 1900, 2, 241–330. [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser, F. Der oberste Baumwuchs. Schweiz. Z. -fFür Forstwes. 1901, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rikli, M. Versuch einer pflanzengeographischen Gliederung der arktischen Wald-und Baumgrenze. Vierteljahresschr. der Nat. Ges. 1904, 49, 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- Pohle, R. Vegetationsbilder aus Nord-Rußland. In Vegetationsbilder; Karsten, G., Schenk, H., Eds.; Gustav Fischer: Jena, Germany, 1907; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, M. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Höhengrenzen der Vegetation im Mittelmeergebiet. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Marek, R. Waldgrenzstudien in den österreichischen Alpen. Petermanns Geogr. Mitt. 1910, 48, 403–425. [Google Scholar]

- Cleve-Euler, A. Skogträdens höjdgränser I trakten af Stora Sjöfallet. Sven. Bot. Tisk. 1912, 6, 496–509. [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren, A. Studier öfvre Nordligaste Skandinaviens Björkskogar; Norstedts Förlag: Stockholm, Sweden, 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Renvall, A. Die periodischen Erscheinungen der Reproduktion der Kiefer an der polaren Waldgrenze. Acta For. Fenn. 1912, 29, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Regel, K. Zur Kenntnis des Baumwuchses und der polaren Waldgrenze. Sitz. der Nat. Ges. Dorpat 1915, 24, 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pohle, R. Wald-und Baumgrenze in Nord-Russsland. Z. der Ges. für Erdkd. Berl. 1917, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann-Jerosch, H. Baumgrenze und Klimacharakter; Beiträge zur geobotanischen Landesaufnahme, Rascher: Zürich, Switzerland, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Köppen, W. Baumgrenze und Lufttemperatur. Petermanns Geogr. Mitt. 1919, 6, 201–203. [Google Scholar]

- Köppen, W. Verhältnis der Baumgrenze zur Lufttemperatur. Meteorol. Z. 1920, 37, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Regel, K. Die Lebensformen der Holzgewächse an der polaren Wald- und Baumgrenze. Sitzungsber.Naturfr. Ges. Dorpat 1921, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hannerz, A.G. Die Waldgrenzen in den östlichen Teilen von Schwedisch Lappland. Sven. Bot. Tidskr. 1923, 17, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gannet, H. The timber-line. J. Am. Geogr. Soc. N. Y. 1899, 31, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, C.J. The unknow father of American timberline research. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2018, 42, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, R.F. The timberlines of northern America and their interpretation. Ecology 1946, 27, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arno, S.F. Timberline, Mountain and Arctic Frontiers; The Mountaineers: Seattle, WA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Schlagintweit, A.; Schlagintweit, H. Neue Untersuchungen über die physikalische Geographie und die Geologie der Alpen; Weigel: Leipzig, Germany, 1854. [Google Scholar]

- De Quervain, A. Die Hebung der atmosphärischen Isothermen in den Schweizer Alpen und ihre Beziehung zu den Höhengrenzen. Gerlands Beiträge zur Geophys. 1904, 6, 481–533. [Google Scholar]

- Scharfetter, R. Das Pflanzenleben der Ostalpen; Deuticke: Wien, Austria, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Han, F.; Yao, Y.; Dai, S.; Wang, C.; Sub, R.; Xu, J.; Zhang, B. Mass elevation effect and its forcing in timberline altitude. J. Geogr. Sci. 2012, 22, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irl, S.D.H.; Anthelme, F.; Harter, D.E.V.; Jentsch, A.; Lotter, E.; Steinbauer, M.J.; Beierkuhnlein, C. Patterns of island treeline elevation—A global perspective. Ecography 2016, 39, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odland, A. Effect of latitude and mountain height on the timberline (Betula pubescens ssp. czerepanovii) elevation along the central Scandinavian mountain range. Fennia 2015, 193, 260–270. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, B. The mass elevation effect of the Tibetan Plateau and its implications for alpine treelines. Int. J. Climatol. 2015, 35, 1833–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, S.; Qi, W.; Whang, J.; Zhang, W. The mass-elevation effect of the central Andes and its implications for the southern hemisphere’s highest treeline. Mt. Res. Dev. 2016, 36, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kašpar, J.; Treml, V. Thermal characteristics of alpine treelines in Central Europe north of the Alps. Clim. Res. 2016, 68, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S.; Qi, W.; He, W.; Wang, J.; Yao, Y. Contribution of mass elevation effect to the altitudinal distribution of global treelines. J. Mt. Sci. 2015, 12, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, F.; Wan, L.; Tan, J.; Liang, T. Characterizing the mass-elevation effect across the Tibetan Plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 2018, 15, 2651–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Grace, J.; Allen, S.; Slack, F. Temperature and stature: A study of temperature in montane vegetation. Funct. Ecol. 1987, 1, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Däniker, A. Biologische Studien über Wald- und Baumgrenze, insbesondere über die klimatischen Ursachen und deren Zusammenhänge. Vierteljahresschr. Naturfr. Ges. Zürich 1923, 63, 1–102. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker, O. Transpiration und Wasserhaushalt in verschiedenen Klimazonen. I. Untersuchungen an der arktischen Baumgrenze in Schwedisch Lappland. Jahrb. für Wiss. Bot. 1931, 75, 494–549. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis, P. Ökologische Studien an der alpinen Baumgrenze. II. Die Schichtung der Windgeschwindigkeit, Luftemperatur und Evaporation über einer Schneefläche. Beih. Zum Bot. Zent. 1934, 52, 310–332. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis, P. Ökologische Studien and der alpinen Baumgrenze. III. Über die winterlichen Temperaturen der pflanzlichen Organe, insbesondere der Fichte. Beih. Bot. Zent. 1934, 52, 333–377. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis, P. Ökologische Studien an der alpinen Baumgrenze. IV. Zur Kenntnis des winterlichen Wasserhaushaltes. Jahrb. Wiss. Bot. 1934, 80, 169–247. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis, P. Ökologische Studien an der alpinen Waldgrenze. V. Osmotischer Wert und Wassergehalt während des Winters in verschiedenen Höhenlagen. Jahrb. Für Wiss. Bot. 1934, 80, 337–362. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, M. Winterliches Bioklima und Wasserhaushalt an der alpinen Waldgrenze. Bioklim. Beiblätter 1935, 2, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, E. Baumgrenzstudien am Feldberg im Schwarzwald. Tharandter Forstl. Jahrb. 1936, 87, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Pisek, A.; Cartellieri, E. Zur Kenntnis der Wasserhaushaltes der Pflanzen. IV. Bäume und Sträucher. Jahrb. der Wiss. Bot. 1939, 88, 222–268. [Google Scholar]

- Pisek, A.; Schiessl, R. Die Temperaturbeeinflußbarkeit der Frosthärte von Nadelhölzern und Zwergsträuchern an der alpinen Waldgrenze. Berd. es Nat. Med. Ver. Innsbr. 1946, 47, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, E. Klimaelemente für Innsbruck (582 m) und Patscherkofel (1909 m) im Zusammenhang mit der Assimilation von Fichten in verschiedenen Höhenlagen. Veröffentlichungen des Mus. Ferdinandeum Innsbr. 1957, 37, 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pisek, A.; Winkler, E. Assimilationsvermögen und Respiration der Fichte (Picea excelsa Link) in verschiedener Seehöhe und der Zirbe (Pinus cembra L.) an der alpinen Waldgrenze. Planta 1958, 51, 518–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüthgen, J. Baumgrenzen in Lappland. Geogr. Anz. 1937, 1, 532–533. [Google Scholar]

- Hustich, I. Pflanzengeographische Studien im Gebiet der Niederen Fjelde im westlichen Finnischen Lappland. Teil I. Ph.D. Thesis, Societas pro fauna et flora Fennica, Helsingfors, Finland, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Aario, L. Waldgrenzen und subrezente Pollenspektren in Petsamo-Lappland. Ann. Acad. Sci. Fenn. 1940, 54, 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- Blüthgen, J. Die polare Baumgrenze. Veröffentlichungen des Dtsch. Wiss. Inst. zu Kph. 1942, 10, 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Blüthgen, J. Dynamik der polaren Baumgrenze in Lappland. Forsch. und Fortschr. 1943, 19, 158–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hustich, I. The scotch pine in northernmost Finland and ist dependence on the climate in the last decades. Acta Bot. Fenn. 1948, 42, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Tranquillini, W. Standortsklima, Wasserbilanz und CO2-Gaswechsel junger Zirben (Pinus cembra L.) an der alpinen Waldgrenze. Planta 1957, 49, 612–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranquillini, W. Die Frosthärte der Zirbe unter besonderer Berücksichtigung autochthoner und aus Forstgärten stammender Jungpflanzen. Forstwiss. Centralbl. 1958, 77, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, E.; Frehner, M.; Frey, H.-U.; Lüscher, P. Gebirgsnadelwäder. Ein praxisorientierter Leitfaden für eine standortsgerechte Waldbehandlung; Haupt: Bern, Switzerland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Aulitzky, H. Grundlagen und Anwendung des vorläufigen Wind-Schnee-Ökogramms. Mitt. der Forstl. Bundesvers. Mariabrunn 1963, 60, 763–834. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, H.; Rochat, P.; Streule, A. Thermische Charakteristik von Hangstandortstypen im Bereich der oberen Waldgrenze (Stillberg, Dischmatal bei Davos). Mitt.der Eidg. Anst. für das Forstl. Vers. 1975, 51, 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Holtmeier, F.K.; Broll, G. Altitudinal and polar treelines in the northern hemisphere—Causes and response to climate change. Polarforschung 2009, 79, 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Boysen-Jensen, P. Die Stoffproduktion der Pflanze; Gustav Fischer Verlag: Jena, Germany, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Ungerson, J.; Scherdin, G. Jahresgang von Photosynthese und Atmung unter natürlichen Bedigungen von Pinus sylvestris L. an ihrer Nordgrenze in der Subarktis. Flora 1968, 157, 391–434. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, E.; Mork, E. Om sambandet mellom temperatur, anding of vekst hos Gran (Picea abies (L.) Karst.). Medd. Fran Det Nor. Skogförsöksvesen 1959, 53, 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski, T.T. Growth and development of trees. Vol. II; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Skre, O. High temperature demands for growth and development in Norway Spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) in Scandinavia. Meldinder Fra Nor. Landbr. 1972, 51, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, G.C.; Fox, J.F. The causes of treeline. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1991, 22, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveinbjörnsson, B.; Kauhanen, H.; Nordell, O. Treeline ecology of mountain birch in the Torneträsk area. Ecol. Bull. 1996, 45, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wieser, G. Carbon dioxide gas exchange of cembran pine (Pinus cembra) at the alpine timberline during winter. Tree Physiol. 1997, 17, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körner, C. A re-assessment of high elevation treeline positions and their explanation. Oecologia 1998, 115, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, D.M.; Malanson, G.P. Environmental variables influencing the carbon balance at the alpine treeline: A modeling approach. J. Veg. Sci. 1998, 9, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J.; Berninger, F.; Nagy, L. Impacts of climate change on the treeline. Ann. Bot. 2002, 90, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, G.; Körner, C. The carbon charging of pines at the climatic treeline: A global comparison. Oecologia 2003, 135, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C.; Paulsen, J. A world-wide study of high altitude treeline temperatures. J. Biogeogr. 2004, 31, 713–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugmann, H.; Zierl, B.; Schumacher, S. Projecting the impacts of climate change on mountain forests and landscapes. In Global change and mountain regions. An overview of current knowledge. In Advances in Global Change Research; Huber, U.M., Bugmann, H.K.M., Reasoner, M.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 477–487. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, P.; Körner, C.; Hoch, G. End of season carbon supply status of wooden species near the treeline in western China. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2006, 7, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C. Alpine treeline. In Functional Ecology of the Global High Elevation Tree Limits; Springer: Basel, Suisse, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Handa, I.T.; Körner, C.; Hättenschwiler, S. A test of the treeline carbon limitation hypothesis by in situ CO2 enrichment and defoliation. Ecology 2005, 86, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammer, A.; Hagedorn, F.; Shevchenko, I.; Leifeld, J.; Guggenberger, G.; Gorcheva, T.; Rigling, A.; Moiseev, P. Treeline shifts in the Ural mountains affect soil organic matter dynamics. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2009, 15, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedorn, F.; Martin, M.; Rixen, C.; Rusch, S.; Bebi, P.; Zürcher, A.; Hättenschwiler, S. Short-term responses to ecosystem carbon fluxes to experimental soil warming at the Swiss alpine treeline. Biogeochemistry 2010, 97, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ran, F.; Chang, R.; Yang, Y.; Luo, J.; Fan, J. Variations in the biomass and carbon pools of Abies georgei along an elevation gradient on the Tibetan Plateau, China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 329, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafius, D.R.; Malanson, G.P. Biomass distribution in dwarf tree, krummholz, and tundra vegetation in the alpine treeline ecotone. Phys. Geogr. 2015, 36, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebermayer, E. Die physikalischen Einwirkungen des Waldes auf Luft und Boden. Band 1. Anhang: Die Ursachen der Schüttekrankheit junger Kiefernpflanzen; C. Krebs: Aschaffenburg, Germany, 1873; pp. 251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, C.H. The causes of timberline on mountains: The role of snow. Plant World 1909, 12, 169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, C.H. Present problems in plant ecology: III Vegetation and altitude. Am. Nat. 1909, 43, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisek, A. Zur Kenntnis der Frosthärte alpiner Pflanzen. Die Naturwissenschaften. 1952, 39, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranquillini, W. Physiological Ecology of the Alpine Timberline—Tree Existence at High Altitudes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Tranquillini, W. Über die physiologischen Ursachen der Wald- und Baumgrenze. Mitt. der Forstl. Bundesvers. Mariabrunn 1967, 75, 457–487. [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Stoll, W.R. Beiträge zur Ökologie der Waldgrenze am Feldberg im Schwarzwald. Angew. Pflanzensoziol. 1954, 2, 824–847. [Google Scholar]

- Larcher, W. Frosttrocknis an der Waldgrenze und in der alpinen Zwergstrauchheide. Veröffentlichungen Mus. Ferdinandeum 1957, 37, 49–81. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer, K. Winterliche Schäden an Zirben nahe der alpinen Waldgrenze. Centralbl. für das gesamte Forstwes. 1959, 76, 232–244. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, P. Engelmannn spruce (Picea engelmannii) at its upper limits on the Front Range, Colorado. Ecology 1968, 49, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmeier, F.-K. Waldgrenzstudien im nördlichen Finnish-Lappland und angrenzenden Nordnorwegen. Rep. Kevo Subarct. Res. Stn. 1971, 8, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, P. An explanation for alpine timberlines. N. Z. J. Bot. 1971, 9, 371–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.N.; Tranquillini, W.; Havranek, W. Cuticuläre Transpiration von Picea abies und Pinus cembra-Zweigen aus verschiedener Seehöhe und ihre Bedeutung für die winterliche Austrocknung der Bäume an der alpinen Waldgrenze. Centralbl. für das gesamte Forstwes. 1974, 91, 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Tranquillini, W. Der Einfluß von Seehöhe und Länge der Vegetationszeit auf das cutikuläre Transpirationsvermögen von Fichtensämlingen im Winter. Ber.Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 1974, 87, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, P. Alpine Timberlines. In Arctic and Alpine Environment; Ives, J.D., Barry, R.G., Eds.; Methuen young books: London, UK, 1974; pp. 371–402. [Google Scholar]

- Platter, W. Wasserhaushalt, cuticuläres Transpirationsvermögen und Dicke der Cutinschichten einiger Nadelholzarten in verschiedendenen Höhenlagen und experimentelle Verkürzung der Vegetationszeit. Ph.D. Thesis, Innsbruck University, Innsbruck, Austria, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, H. Types of microclimate at high elevations. In Mountain Environments and Subalpine Tree Growth; Benecke, U., Davis, M., Eds.; New Zealand Forest Service Technical Paper; New Zealand Forest Service: Welligton, New Zealand, 1980; Volume 70, pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sowell, J.P.; Koutnik, K.; Lansing, A.J. Cuticular transpiration of whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) within an Sierra Nevadan timberline ecotone, U.S.A. Arct. Alp. Res. 1982, 14, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranquillini, W. Frost-drought an its ecological significance. In Physiological Plant Ecology II—Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology, New Series; Lange, O.L., Nobel, P.S., Osmond, C.B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1982; pp. 379–400. [Google Scholar]

- DeLucia, E.V.; Berlyn, G.P. The effect of mountain elevation on leaf cuticle thickness and cuticular transpiration in balsam fir. Can. J. Bot. 1984, 62, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowell, J.B. Winter relations of trees at alpine timberline. In Establishment and Tending of Subalpine Forersts: Research and Management, Proceeding 3rd IUFRO Workshop; Turner, H., Tranquillini, W., Eds.; Eidgenössische Anstalt für das forstliche Versuchswesen: Birmensdorf, Germany, 1985; pp. 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, D.M. Patterns of winter desiccation in krummholz forms of Abies lasiocarpa at treeline sites in Glacier National Park, Montana, USA. Geogr. Ann. 2001, 83, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellenberg, H. Vegetation Mitteleuropas mit den Alpen in ökologischer Sicht, 2nd ed.; Verlag Eugen Ulmer: Stuttgart, Deutschland, 1963; p. 981. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, H.; Breckle, S. Ökologie der Erde, Band 3, Spezielle Ökologie der Gemäßigten und arktischen Zonen Euro-Nordasiens; Gustav Fischer: Stuttgart, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, M. Vegetationszonen der Erde; Klett-Perthes: Gotha/Stuttgart, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, A.M.; Crawford, R.M.M. Winter desiccation stress and resting bud viability in relation to high altitude survival in Sorbus aucuparia L. Flora 1982, 172, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, P.M.; Slatyer, R.O. Water relations of Eucaplytus pauciflora near the alpine tree line in winter. Tree Physiol. 1988, 4, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slatyer, R.O.; Noble, I.R. Dynamics of Montane Treelines. In Landscape Boundaries: Consequences for Biotic Diversity and Ecological Flows, Ecological Studies; Hansen, A., Di Castri, F., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 346–359. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, P.J.; Chabot, B.F. Winter water relations of the tree-line plant species, New Hampshire. Arct. Alp. Res. 1978, 10, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmeier, F.-K. Influence of wind on tree physiognomy at the upper timberline in the Colorado Front Range. In Mountain Environments and Subalpine Tree Growth, Proceedings of the IUFRO Workshop, Christchurch, New Zealand, 1979; Benecke, D., Ed.; New Zealand Forest Service Technical Paper: Wellington, New Zealand, 1980; pp. 247–262. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, P.J. Causes of coniferous timberline in the northern Appalachian mountains. In Mountain Environments and Subalpine Tree Growth; Benecke, U., Davis, M.R., Eds.; New Zealand Forest Service Technical Paper: Wellington, New Zealand, 1980; pp. 231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, J.L.; Smith, W.K. Influence of wind exposure on needle deciccation and mortality for timberline conifers in Wyoming, U.S.A. Arct. Alp. Res. 1983, 15, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, J.L.; Smith, W.K. Wind effects on needles of timberline conifers: Seasonal influences on mortality. Ecology 1986, 67, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J. Cuticular water loss unlikely to explain treeline in Scotland. Oecologia 1990, 84, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmeier, F.-K. Blowing snow and sand blast shaping tree physiognomy at certain treeline microsites—A review. Geoöko 2016, 37, 201–233. [Google Scholar]

- Holtmeier, F.-K.; Broll, G. Treeline advance—Driving processes and adverse factors. Landsc. Online 2007, 1, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuner, G. Frost resistance at the upper timberline. In Trees at Their Upper Limit. Treelife Limitation at the Alpine Timberline—Plant Ecophysiology; Wieser, G., Tausz, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Wieser, G.; Tausz, M. Current concepts for treelife limitation at the upper timberline. In Trees at Their Upper Limit. Treelife Limitation at the Alpine Timberline—Plant Ecophysiology; Wieser, G., Tausz, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrig-Fasel, J.; Guisan, A.; Zimmermann, N.E. Evaluating thermal treeline indicators based on air and soil temperature using air-to-soil temperature transfer model. Ecol. Model. 2008, 213, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, J.; Körner, C. A climate-based model to predict treeline position around the globe. Alp. Bot. 2014, 124, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retzer, J.L. Alpine soils. In Arctic and Alpine Environment; Ives, J.D., Barry, R.G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1974; pp. 771–802. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, P.S.; Nordell, O. Effects of soil temperature on nitrogen economy and growth of mountain birch seedlings near its presumed low temperature distribution limit. Ecoscience 1996, 3, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, K. Die Lage der oberen Waldgrenze in den Gebirgen der Erde und ihr Abstand zur Schneegrenze. Kölner Geogr. Arb. 1955, 5, 277. [Google Scholar]

- Holtmeier, F.-K. Ecological aspects of climatically-caused timberline fluctuations. In Mountain Environments in Changing Climates; Beniston, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 220–233. [Google Scholar]

- Büntgen, U.; Frank, D.C.; Kaczka, R.; Verstege, A.; Zwijacz-Kozica, T.; Esper, J. Growth response to climate in a multi-species tree-ring network in the western Carpathian Tatra Mountains, Poland, Slovakia. Tree Physiol. 2007, 27, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohsawa, M. An interpretation of latitudinal patterns of forest limits in south and east Asian mountains. J. Ecol. 1990, 78, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno de Mesquita, C.P.; Tillmann, L.S.; Bernard, C.D.; Rosemond, K.C.; Molotsch, N.P.; Suding, K.N. Topographic heterogeneity explains patterns of vegetation response to climate change (1972-2008) across a mountain landscape, Niwot Ridge, Colorado. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2018, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, H. Die globale Hangbestrahlung als Standortfaktor bei Aufforstungen in der subalpinen Stufe. Mitt. der Schweiz. Anst. für das Forstl. Vers. 1966, 42, 1110–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Holtmeier, F.-K.; Broll, G. The influence of tree islands and microtopography on pedoecological conditions in the forest-alpine tundra ecotone on Niwot Ridge, Colorado Front Range, U.S.A. Arct. Alp. Res. 1992, 24, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broll, G.; Holtmeier, F.-K. Die Entwicklung von Kleinreliefstrukturen im Waldgrenzökoton der Front Range (Colorado, USA) unter dem Einfuss leewärts wandernder Ablegergruppen (Picea engelmannii und Abies lasiocarpa). Erdkunde 1994, 48, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, C.A.; Liston, G.E.; Reiners, W.A. Snow redistribution by wind and interacting with vegetation at upper treeline in the Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming, U.S.A. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2002, 34, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, M. Positive feedback between tree establishment and patterns of subalpine forests advancement, Glacier National Park, Montana, U.S.A. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2005, 37, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alftine, K.J.; Malanson, G.P. Directional positive feedback and pattern at an alpine treeline. J. Veg. Sci. 2004, 15, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmeier, F.-K. Relocation of snow and its effects in the treeline ecotone with special regard to the Rocky Mountains, the Alps and Northern Europe. Die Erde 2005, 136, 343–373. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand, T.; Camarero, J.J.; Rüger, N.; Gutiérrez, E. Abrupt population changes at treeline ecotones along smooth gradients. J. Ecol. 2006, 94, 880–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, H.C.; Bourgeron, P.S.; Mujica-Crapanzano, L.R. Tree spatial patterns and environmental relationships in the forest-alpine tundra ecotone at Niwot Ridge, Colorado, USA. Ecol. Res. 2008, 23, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmeier, F.-K.; Broll, G. Wind as an ecological agent at treelines in North America, the Alps, and the European Subarctic. Phys. Geogr. 2010, 31, 203–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, G.P.; Kipfmueller, K.F. Multi-scale influences of slope aspect and spatial pattern on ecotonal dynamics at upper treeline in the Southern Rocky Mountains, U.S.A. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2010, 42, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmeier, F.-K.; Broll, G. Feedbacks of clonal groups and tree clusters on site conditions at the treeline: Implications for treeline dynamics. Clim. Res. 2017, 73, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montpellier, E.E.; Soulé, P.T.; Knapp, P.A.; Shelley, J.S. Divergent growth rates of Larix lyallii Parl) in response to microenvironmental variability. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2018, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, A.; Eitel, J.U.H.; Vierling, L.A.; Johnson, D.M.; Griffin, K.L.; Bodman, N.; Jensen, J.E.; Greaves, H.E.; Meddens, A.J.H. Terrestrial lidarscanning reveals fine-scale linkages between microstructure and photosynthetic functioning of small-stature spruce trees at the forest-tundra ecotone. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 269, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmeier, F.-K.; Broll, G. Subalpine forest and treeline ecotone under the influence of disturbances: A review. J. Environ. Prot. 2018, 9, 815–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolmachev, A.I. Die Erforschung einer entfernten Waldinsel in der Großlandtundra. Colloq. Geogr. 1970, 12, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Payette, S.; Gagnon, R. Tree-line dynamics in Ungava Peninsula, northern Québec. Holarct. Ecol. 1979, 2, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, J.D.; Hansen-Bristow, K.J. Stability and instability of natural and modified upper timberline landscapes in the Colorado Rocky Mountains, U.S.A. Mt. Res. Dev. 1983, 3, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmeier, F.-K. Human impacts on high altitude forests and upper timberline with special reference to middle latitudes. In Human Impacts and Management of Mountain Forests; Fujimori, T., Kimura, M., Eds.; Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute: Ibaraki, Japan, 1987; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Löffler, J.; Lundberg, A.; Rössler, O.; Bräuning, A.; Jung, G.; Pape, R.; Wundram, D. The alpine treeline under changing land use and changing climate: Approach and preliminary results from continental Norway. Nor. Geogr. Tidskr. 2004, 58, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonelli, G.; Pelfini, M.; Battipaglia, G.; Cherubini, P. Site aspect influence on climatic sensitivity over time of a high-altitude Pinus cembra tree-ring network. Clim. Chang. 2009, 96, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsh, M.A.; Hulme, P.E.; McGlone, M.S.; Duncan, R.P. Are treelines advancing? A global meta-analysis of treeline response to climate warming. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullman, L. Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) treeline ecotone performance since the mid-1970s in the Swedish Scandes—Evidence of stability and minor change from repeat surveys and photography. Geoöko 2007, 35, 23–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kullman, L. One century of treeline change and stability—An illustrated view from the Swedish Scandes. Landsc. Online 2010, 17, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullman, L. The alpine treeline ecotone in the southwestern Swedish Scandes: Dynamics on different scales. In Ecotones between Forest and Grassland; Myster, R.W., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kullman, L. Higher-than-present Medieval pine (Pinus sylvestris) treeline along the Swedish Scandes. Landscape online 2015, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bruening, J.M.; Tran, T.J.; Bunn, A.G.; Weiss, S.B.; Salzer, M.W. Fine scale modeling a bristlecone treeline position in the Great Basin, USA. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, M.; Kruse, S.; Eppl, L.; Kolmogorov, A.; Nikolaev, A.N.; Heinrich, E.; Jeltsch, F.; Pestryakova, L.A.; Zibulski, R.; Herzschuh, U. Dissimilar response of larch stands in northern Siberia to increasing temperatures—A field and simulation based study. Ecology 2017, 98, 2343–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanomi, G.; Rita, A.; Allevato, E.; Cesarano, G.; Saulino, L.; Di Pasquale, G.; Alegrezza, M.; Pesaresi, S.; Borghetii, M.; Rossi, S. Anthropogenic and environmental factors affect the treeline position of Fagus sylvatica along the Apennines (Italy). J. Biogeogr. 2018, 45, 2595–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Sharma, S.; Dghyani, P.P. Himalayan arc and treeline: Distribution, climate change responses and ecosystem properties. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 1997–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, G.; Oberhuber, W.; Gruber, A. Effects of climate change at treeline: Lessons from space-for-time studies, manipulative experiments, and long-term observational records in the Central Austrian Alps. Forests 2019, 10, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rössler, O.; Löffler, J. Uncertainties of treeline alterations due to climatic change during the past century in the Norwegian Scandes. Geöko 2007, 28, 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Moyes, A.B.; Germino, M.J.; Kueppers, L.M. Moisture rivals temperature in limiting phyotosynthesis by trees establishing beyond their cold-edge range limit under ambient and warm conditions. New Phytol. 2015, 4, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, L.; Agafonov, L.; Ljungqvist, F.C.; Churakova, O.; Düthorn, E.; Esper, J.; Hülsmann, L.; Kirdyanov, A.V.; Moiseev, P.; Myglan, V.S.; et al. Diverse growth trends and climate responses across Eurasian’s boreal forest. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, B.; Duncan, R. A novel frame for disentangling the scale-dependent influence of abiotic factors on alpine treeline position. Ecography 2014, 37, 838–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, T.V.; Werkman, B.R.; Crawford, R.M.M. The tundra-taiga interface and its dynamics, concepts and applications. Ambio Spec. Rep. 2002, 12, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Juntunen, V.; Neuvonen, S.; Norokorpi, Y.; Tasanen, T. Potential for timberline advance in northern Finland as revealed by monitoring during 1983–1999. Arctic 2002, 55, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A.H.; Fastie, C. Spatial and temporal variability in the growth and climate response of treeline trees in Alaska. Clim. Chang. 2002, 52, 481–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmeier, F.-K.; Broll, G. Sensitivity and response of northern hemisphere altitudinal and polar treelines to environmental change at landscape and local scales. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2005, 14, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, G.-R.; Beißner, S.; Pott, R. Climate change and high mountain vegetation shifts. In Mountain Ecosystems. Studies in Treeline Ecology; Broll, G., Keplin, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Juntunen, V.; Neuvonen, S. Natural regeneration of Scots pine and Norway spruce close to the timberline in Northern Finland. Silva Fenn. 2006, 40, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlgemuth, T.; Bugmann, H.; Lische, H.; Tinner, W. Wie rasch ändert sich die Waldvegetation als Folge von raschen Klimaveränderungen? Forum für Wissen 2006, 1, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Danby, R.K.; Hik, D.S. Variability, contingency and rapid change in recent subarctic alpine tree line dynamics. J. Ecol. 2007, 95, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.; Hagedorn, F.; Moiseev, P.; Bugmann, H.; Shiyatov, S.; Mazepa, V.; Rigling, A. Expanding forest and changing growth forms in Siberian larch at the polar Urals treeline during the 20th century. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2008, 14, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, G.; Kremenetski, K.V.; Beilman, D.W. Climate change and the northern Russian treeline zone. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 2008, 363, 2285–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Germino, M.J.; Johnson, D.M.; Reinhardt, K. The altitude of alpine treeline: A bellwether of climate change effects. Bot. Rev. 2009, 75, 163–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bogaert, R.; Haneca, K.; Hoogester, J.; Jonasson, C.; De Papper, M.; Callaghan, T.V. A century of tree line changes in subarctic Sweden shows local and regional variability and only minor influence of 20th century climate warming. J. Biogeogr. 2011, 38, 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batllori, E.; Camarero, J.J.; Gutiérrez, E. Climatic drivers of tree growth and recent recruitment at the Pyrenean alpine tree line ecotone. In Ecotones, 1st ed.; Myster, R.W., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 247–289. [Google Scholar]

- Aakala, T.; Hari, P.; Dengel, S.; Newberry, S.L.; Mizunuma, T.; Grace, J. A prominent stepwise advance of the treeline in north-east Finland. J. Ecol. 2014, 102, 1582–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, S.; Jump, A.S. Consequences if treeline shifts for the diversity and function of high altitude ecosystems. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2014, 46, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broll, G.; Jokinen, M.; Aradottir, A.L.; Cudlin, P.; Dinca, L.; Gömöryová, E.; Grego, S.; Holtmeier, F.-K.; Karlinski, L.; Klopcic, M.; et al. Working Group 2: Indicators of changes in the treeline ecotone. In SENSFOR Deliverable 5. COST Action ES 1203: Enhancing the Resilience Capacity of Sensitive Mountain Forest Ecosystems and Environmental Change; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schickhoff, U.; Bobrowski, M.; Böhner, J.; Bürzle, B.; Chaudhary, R.P.; Gerlitzky, L.; Lange, J.; Müller, M.; Scholten, T.; Schwab, N. Climate change and treeline dynamics in the Himalaya. In Climate Change, Glacier Response, and Vegetation Dynamics in the Himalaya; Singh, R.B., Schickhoff, U., Mal, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 271–306. [Google Scholar]

- Cudlin, P.; Klopčič, M.; Tognetti, R.; Mális, F.; Alados, C.L.; Bebi, P.; Grunewald, K.; Zhiyanski, M.; Andonowski, V.; La Porta, N.; et al. Drivers o treeline shift in different European Mountains. Contribution to CR Special 34 SENSFOR: Resilience in SENSItive mountain FORest ecosystems under environmental change. Clim. Res. 2017, 73, 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.E.; Wilson, T.L.; Sherriff, R.L.; Walton, J. Warming drives a front of white spruce establishment near western treeline, Alaska. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017, 23, 5509–5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgolaski, F.E.; Hofgaard, A.; Holtmeier, F.-K. Sensitivity to environmental change of the treeline ecotone and its associated biodiversity in European mountains. Clim. Res. 2017, 73, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.D.; Dufour Tremblay, G.; Jameson, R.G.; Mamet, S.; Trant, A.J.; Walker, X.J.; Boudreau, S.; Harper, K.; Henry, G.H.R.; Hermanutz, L.; et al. Reproduction as a bottleneck to treeline advance across the circumarctic forest tundra ecotone. Ecography 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochner, M.; Bugmann, H.; Nötzli, M.; Bigler, C. Among-tree variability and feedback effects result in different growth responses to climate change at the upper treeline in the Swiss Alps. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 7937–7953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullman, L.; Öberg, L. A one hundred-year study of the upper limit of tree growth (Terminus arboreus) in the Swedish Scandes—Updated and illustrated change in an historical perspective. Int. J. Res. Geogr. 2018, 4, 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cazolla Gatti, R.; Velichevskaja, A.; Dudko, A.; Fabbio, L.; Battipaglia, G.; Liang, J. Accelerating upward treeline shift in the Altai Mountains under last-century climate change. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofgaard, A.; Ols, C.; Drobyshev, I.; Kirchhefer, A.; Sandberg, S.; Söderström, L. Non-stationary response of tree growth to climate trends along the Arctic margin. Ecosystems 2019, 22, 434–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, H. Palynological and Paleoclimatic Study of the Late Quaternary Displacement of the Boreal Forest-Tundra Ecotone in Keewatin and Mackenzie N.W.T., Canada; Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Vorren, K.-D.; Mørkved, B.; Bortenschlager, S. Human impact on the Holocene forest line in the Central Alps. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 1993, 2, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, B.; Faarlund, T. The present and the Holocene birch belt in Norway. In Paleoclimate Research; Frenzel, B., Alm, V., Eds.; Fischer: Innsbruck, Austria, 1996; pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kullman, L.; Kjällgren, L. A coherent postglacial tree-limit chronology (Pinus sylverstris L.) for the Swedsish Scandes: Aspects of paleoclimatic and “recent warming”, based on megafossil evidence. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2000, 32, 419–428. [Google Scholar]

- Gervais, B.R.; Macdonald, G.M.; Snyder, J.A.; Kremenetski, C.V. Pinus sylvestris treeline development and movement on the Kola Peninsula of Russia: Pollen and stomate evidence. J. Ecol. 2002, 90, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinner, W.; Theurillat, J.-P. Uppermost limit, extent, and fluctuations of the timberline and treeline ecocline in the Swiss Alps during the past 11.500 years. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2003, 35, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esper, J.; Shiyatov, S.G.; Mazepa, V.S.; Wilson, R.J.S.; Graybill, D.A.; Funkhouser, G. Temperature-sensitive Tien Shan tree ring chronologies show multi-centennial growth trends. Clim. Dyn. 2003, 21, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinner, W.; Kaltenrieder, P. Rapid responses of high-mountain vegetation to early Holocene environmental changes in the Swiss Alps. J. Ecol. 2005, 93, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helama, S.; Timonen, M.; Holopainen, J.; Ogurtsov, M.; Mielikäinen; Eronen, M.; Lindholm, M.; Meriläinen, J. Summer temperature variations in Lapland during the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age relative to natural instability of multi-decadal and multi-centennial scales. J. Quat. Sci. 2009, 24, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.G.; Hatton, J.; Selby, K.A.; Leng, N.J.; Christie, N. Multi-proxy study of Holocene environmental change and human activity in the Central Apennine Mountains, Italy. J. Quat. Sci. 2013, 28, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononov, Y.M.; Friedrich, M.; Boettger, T. Regional summer temperature reconstruction in the Khibiny low mountains (Kola Pensinsula, NW Russia) by means of tree-ring width during the last four centuries. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2009, 41, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazepa, V.S. Climate dependent dynamics of the upper treeline ecotone in the Polar Urals for the last millennium. In Proceedings of the XIII World Forestry Congress, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 18–23 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Väliranta, M.; Kaakinen, A.; Kuhry, P.; Kultti, S.; Salonen, J.S.; Seppä, H. Scattered late-glacial and early Holocene tree populations as dispersal nuclei for forest development in north-eastern European Russia. J. Biogeogr. 2010, 38, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffler, H.; Nicolussi, K.; Patzelt, G. Postglaziale Waldgenzentwicklung in den Westtiroler Zentralalpen. Gredleriana 2011, 11, 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Magyari, E.K.; Jakab, G.; Bálint, M.; Kern, Z.; Buczko, K.; Braun, M. Rapid vegetation response to Lateglacial and early Holocene climatic fluctuation in the South Carpathian Mountains (Romania). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2012, 32, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofgaard, A.; Tømmervik, H.; Rees, G.; Hansen, F. Latitudinal forest advance in northernmost Norway since the early 20th century. J. Biogeogr. 2013, 40, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badino, F.; Ravazzi, C.; Vallè, F.; Pini, R.; Aceiti, A.; Brunetti, M.; Champvillair, E.; Maggi, V.; Maspero, F.; Prego, E.; et al. 8800 years of high-altitude vegetation and climate history at the Rutor Glacier forefield, Italian Alps. Evidence of middle Holocene timberline rise and glacier contraction. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2018, 195, 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leúnda, M.; González-Sampéris, P.; Gil-Romera, G.; Bartolomé, M.; Belmonte-Ribas, A.; Goméz-García, D.; Kaltenrieder, P.; Rubiales, J.M.; Schwörer, C.; Tinner, W.; et al. Ice cave reveals environmental forcing of long-term Pyrenean tree line dynamics. J. Ecol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liao, M.; Ni, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Treeline composition and biodiversity change on the southeastern Tibetan Plateau during the past millennium inferred from high-resolution alpine pollen record. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2019, 206, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]