Optimizing the Stand Density of Robinia pseudoacacia L. Forests of the Loess Plateau, China, Based on Response to Soil Water and Soil Nutrient

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.1.1. Study Site

2.1.2. Investigation of Standard Plots

2.1.3. Detection of Soil Nutrients and Soil Particle Sizes

2.1.4. Monitoring of SMC, SER and VTR

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution of Soil Water and Soil Nutrient Resources

3.1.1. Spatial Distribution of SD, VTR, SMC, and SER

3.1.2. Spatial Distribution of Soil Nutrients

3.1.3. Vertical Distribution of the Soil Water and Soil Particles

3.1.4. Statistical Analysis of the Soil Water and Soil Nutrient Resources

3.2. Analysis of Stand Structure Optimization of R. pseudoacacia Forest

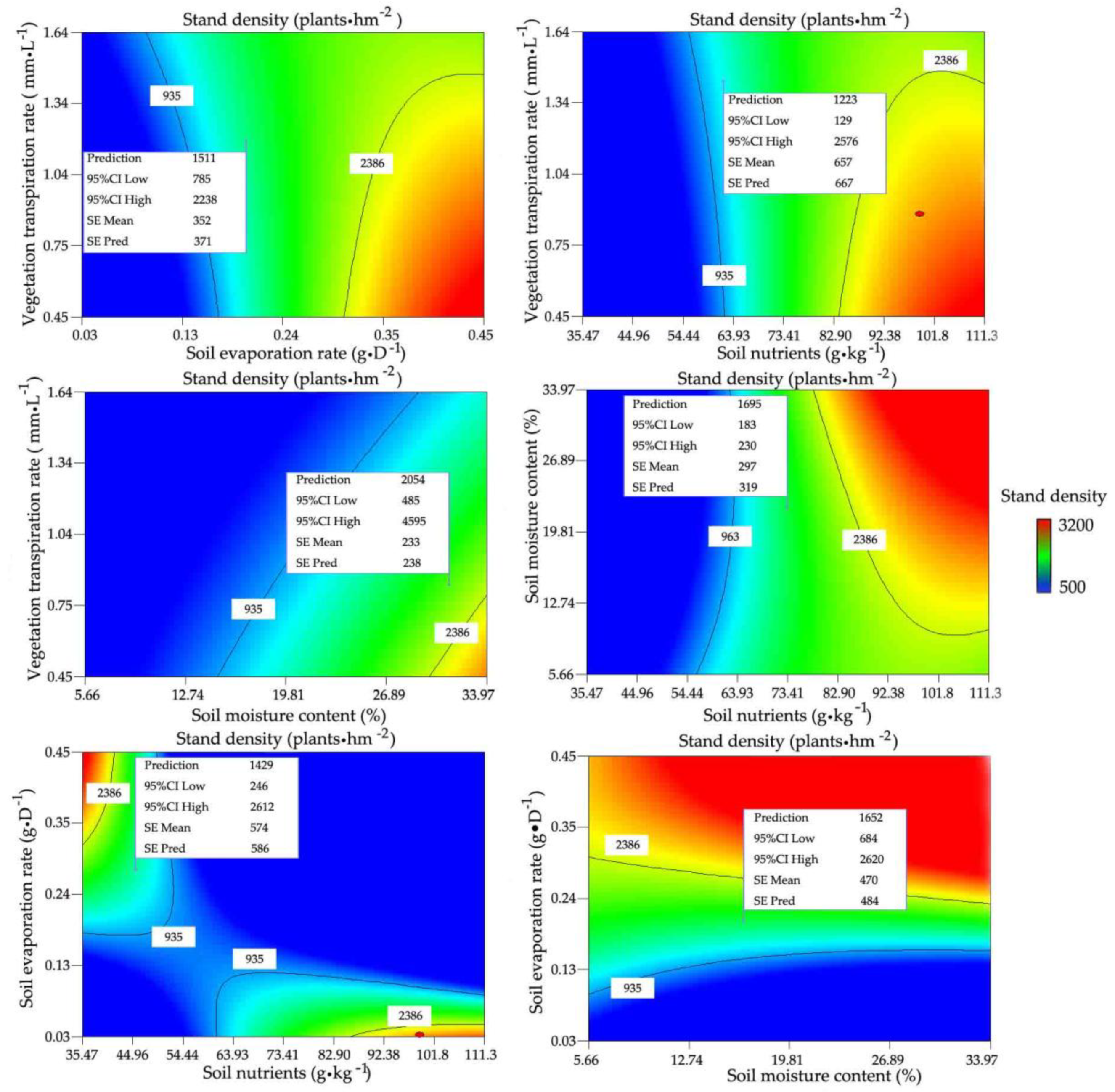

3.2.1. Relationships between Stand Density and Water and Nutrients

3.2.2. Determining the Optimal Stand Density and Its Ranges for R. pseudoacacia Forest

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of SMC, SER, and Soil Nutrients on Stand Density

4.2. Effects of the VTR on Stand Density

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, X.N.; Huang, Y.M.; Li, E.G.; Li, X.Y.; Guo, W.H. Effects of vegetation types on soil water dynamics during vegetation restoration in the Mu Us Sandy land, northwestern China. J. Arid. Land. 2017, 9, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.N.; Huang, Y.M.; Li, E.G.; Li, X.Y.; Guo, W.H. Effects of rainfall and vegetation to soil water input and output processes in the Mu Us Sandy land, northwest China. Catena 2018, 9, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q.K.; Zhao, W.J.; Ma, H.; Wang, R.; Ai, N. The dynamic trend of soil water content in artificial forests on the Loess Plateau, China. Forests 2016, 7, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Singh, B.; Singh, R.R. Changes in physico-chemical, microbial and enzymatic activities during restoration of degraded sodic land: Ecological suitability of mixed forest over monoculture plantation. Catena 2012, 96, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Pandey, V.C.; Singh, B.; Singh, R.R. Ecological restoration of degraded sodic lands through afforestation and cropping. Ecol. Eng. 2012, 43, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.H.; Fu, B.J. Evolution of ecosystem services in the Chinese Loess Plateau under climatic and land use changes. Global Planet. Chang. 2013, 101, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.H.; Fu, B.J.; He, C.S.; Lü, Y.H. Variation of ecosystem services and human activities: a case study in the Yanhe Watershed of China. Acta Oecol. 2012, 44, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staska, B.; Essl, F.; Samimi, C. Density and age of invasive Robinia pseudoacacia modulate its impact on floodplain forests. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2014, 15, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.B.; Xue, Y.Y.; Li, Z.S.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Gao, G.Y.; Liu, G.H.; Fu, B.J. Soil moisture decline following the plantation of Robinia pseudoacacia forests: Evidence from the Loess Plateau. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2018, 412, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; ShangGuan, Z.P.; Li, R. Effects of the grain-for-green program on soil erosion in China. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2012, 27, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.; Garcia-Fayos, P.; Hu, S.; Jiao, J.Y. The effect of Robinia pseudoacacia afforestation on soil and vegetation properties in the Loess Plateau (China): A chronosequence approach. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2016, 375, 146–158. [Google Scholar]

- Vítková, M.; Müllerová, J.; Sádlo, J.; Pergl, J.; Pyšek, P. Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) beloved and despised: A story of an invasive tree in Central Europe. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2017, 384, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Z.B.; Yu, B.F.; Han, Y.G. Spatiotemporal variations in annual sediment yield from the middle yellow river, China, 1950–2010. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2015, 20, 04014090. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.J.; Lu, C.H. Evaluation of land-use change effects on runoff and soil erosion of a hilly basin—the Yanhe River in the Chinese Loess Plateau. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.X.; Lü, Y.H.; Fu, B.J.; Harris, P.; Wu, L.H. Quantifying the spatio-temporal drivers of planned vegetation restoration on ecosystem services at a regional scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayas, J.M.R.; Bullock, J.M. Enhancement of biodiversity and ecosystem services by ecological restoration: a meta-analysis. Science 2009, 325, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Lü, Y.; Fu, B.; Comber, A.J.; Harris, P.; Wu, L. Gauging policy-driven large-scale vegetation restoration programmes under a changing environment: their effectiveness and socio-economic relationships. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607–608, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.K.; Li, Z.Y.; Zhu, Q.K.; Zhu, D.H.; Liu, H.F. Climatic and drought characteristics in the loess hilly gully region of China from 1957 to 2014. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178701. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.N.; Zhu, Q.K.; Zhao, W.J.; Zhao, X.K. The drought trend and its relationship with rainfall intensity in the Loess Plateau of China. Nat. Hazards. 2015, 77, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, M.U.F. The temperature dependence of soil organic matter decomposition, and the effect of global warming on soil organic C storage. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1995, 27, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.Z.; Lei, X.D.; Li, X.F. Study on Spatial structure optimizing model of stand selection cutting. Sci. Ailvae Ainicae 2014, 40, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, G.Y.; Klaus, V.G.; Hu, Y.B.; Xu, H. Structure-Based Forest Management; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.F.; Hui, G.Y.; Zhao, Z.H.; Hu, Y.B. The bivariate distribution characteristics of spatial structure in natural Korean pine broad-leaved forest. J. Veg. Sci. 2012, 23, 1180–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.X.; Li, X.Y.; Li, J.; Guo, M.X.; Liu, X. Study on suitable vegetation cover on Loess Area based on soil water balance. Sci. Ailvae Ainicae 2007, 43, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, D.K.; Wang, H.; Li, X.B.; Liu, H.H.; Li, X.H. Estimation of the ecological water requirement for natural vegetation in the Ergune River basin in Northeastern China from 2001 to 2014. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 92, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Huang, M.B.; Gallichand, J.Q.; Shao, M.A. Optimization of plant coverage in relation to water balance in the Loess Plateau of China. Geoderma 2012, 173–174, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Study on Construction of Ecological Rehabilitation System in Aquatic-Terrestrial Ecotone, Lijinag River; Beijing Forestry University: Beijng, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bochet, E.; García-Fayos, P. Factors controlling vegetation establishment and aater erosion on motorway slopes in Valencia, Spain. Restor. Ecol. 2004, 12, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochet, E.; García-Fayos, P.; Tormo, J. How can we control erosion of roadslopes in semiarid mediterranean areas? Soil improvement and native plant establishment. Land Degrad. Dev. 2010, 21, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, M.B.; Lian, J.J. Spatial distributions of optimal plant coverage for the dominant tree and shrub species along a precipitation gradient on the central Loess Plateau. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 2015, 206, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.L.; Jia, X.X.; Zhu, Y.J.; Shao, M.A. Long-term temporal variations of soil water content under different vegetation types in the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2017, 158, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhang, H.Y.; Zhang, Z.D. Spatially explicit assessment of ecosystem services in China’s Loess Plateau: Patterns, interactions, drivers, and implications. Global Planetary Chang. 2018, 161, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shao, M.A.; Li, Y.Y. Study on relationship between growth of artificial Robinia Pseudocacia and soil desiccation in the Loess Plateau of northern Shanxi Province. Sci. Ailvae Ainicae 2004, 40, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.P.; Shao, M.A. Soil water carrying capacity of apricot forest on Loess Region in northern Shaanxi. Sci. Ailvae Ainicae 2009, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.F.; Bi, H.X.; Ren, Q.F.; Xu, H.S.; Cai, Z.C.; Dan, W.; Liao, W.C. Soil moisture stochastic model in Pinus tabuliformis forestland on the Loess Plateau, China. Water 2017, 9, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.R.; Bi, H.X.; Wei, X.; Kong, L.X.; Wang, N.; Zhou, Q.Z. Response of soil moisture to single-rainfall events under three vegetation types in the gully region of the Loess Plateau. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Q.; Yu, X.X.; Jia, G.D. Water uptake by coniferous and broad-leaved forest in a rocky mountainous area of northern China. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 2019, 265, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Scott, T.K. Intensity of hydrostimulation for the induction of root hydrotropism and its sensing by the root cap. Plant. Cell Environ. 1993, 16, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, G.; Corkidi, G.; Eapen, D.; Lledías, F.; Cárdenas, L.; Cassab, G. Root hydrotropism and thigmotropism in\r, arabidopsis thaliana\r, are differentially controlled by redox status. Plant. Signal. Behav. 2017, 12, e1305536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, A.; Allott, T.; Evans, M.; Joosten, H.; Stoneman, R. Peatland Restoration and Ecosystem Services (Science, Policy and Practice) || Ecosystem Services, Degradation and Restoration of Peat Swamps in the South East Asian Tropics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 253–288. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, D. Hydrotropism—How roots search for water. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 2759–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Wu, X.F.; Hao, J.; Li, K.L.; Liu, J. The adaptability and decontamination effect of four kinds of woody plants in constructed wetland environment. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014, 34, 916–924. [Google Scholar]

- Belnap, J.; Welter, J.R.; Grimm, N.B.; Barger, N.; Ludwig, J.A. Linkages between microbial and hydrologic processes in arid and semi-arid watersheds. Ecology 2005, 86, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyon, R.G.; Theiveyanathan, S.; Doody, T.M. Impacts of tree plantations on groundwater in south-eastern Australia. Aust. J. Bot. 2006, 54, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Tang, C.S.; Xu, S.K.; Gong, X.P.; Shi, B.; Inyang, H.I. Effects of soil characteristics on moisture evaporation. Eng. Geol. 2018, 239, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, Z.P.; Zheng, S.X. Ecological properties of soil water and effects on forest vegetation in the Loess Plateau. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2006, 13, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; He, W.; Na, L. Study on appropriate of Pinus tabulaeformis and Robinia Pseudoacacia for soil and water conservation forests in Loess area. Sci. Soil Water Conserv. 2007, 5, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, A.; Vassilev, N.; Alguacil, M.M.; Roldán, A.; Azcón, R. Increased plant growth, nutrient uptake, and soil enzymatic activities in a desertified mediterranean soil amended with treated residues and inoculated with native mycorrhizal fungi and a plant growth-promoting yeast. Soil Sci. 2004, 169, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazary, M.E.H. Effect of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer on yield and nutritional quality of jumbo grass (Sorghum Grass x Sudan Grass). Adv. Animal Vet. Sci. 2015, 3, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.D.; Ye, Y.H.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, D.H.; Hang, Y.Y. Study on soil nutrients and moisture as well as soil microorganism at grassland-forestland interface in gully region of Loess Plateau. J. Northwest. Agric. For. Univ. 2007, 35, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.M.; Jia, G.D.; Liu, Z.Q.; Wang, D.D.; Yu, X.X. Populus simonii Carr. Reduces wind erosion and improves soil properties in Northern China. Forests 2019, 10, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorný, R. Sap flux simulation and tree transpiration depending on tree position within stand of different densities. Phyton Ann. Rei Bot. A 2000, 40, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Asbjornsen, H.; Tomer, M.D.; Gomez-Cardenas, M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Greenan, C.M.; Schilling, K. Tree and stand transpiration in a Midwestern bur Oak savanna after elm encroachment and restoration thinning. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2007, 247, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.N.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, Z.; Hao, R.; Huang, M. Characteristics of water consumption by Robinia pseudoacacia forest on Loess Plateau of western Shanxi Province, China. Chin. J. Ecol. 2012, 31, 2736–2741. [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen, J.; Wihersaari, M.; Savolainen, I. Industrial ecosystem in the Finnish forest industry: Using the material and energy flow model of a forest ecosystem in a forest industry system. Ecol. Econ. 2001, 39, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, T.J.; Dosskey, M.G.; Hoagland, K.D. Filter strip performance and processes for different vegetation, widths, and contaminants. J. Environ. Qual. 1999, 28, 1479–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Lu, S.; Jin, X.; Gan, S. Contaminant removal from low-concentration polluted river water by the bio-rack wetlands. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 24, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borin, M.; Bigon, E. Abatement of NO3-N concentration in agricultural waters by narrow buffer strips. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 117, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.R.; Bi, H.X.; Yu, X.X.; Jia, G.D.; Wang, D.D.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Liu, Z.Q. A vegetation configuration pattern with a high-efficiency purification ability for TN, TP, AN, AP, and COD based on comprehensive assessment results. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stand Density (plants·hm−2) | Elevation (m) | Slope (°) | Av. Tree High (m) | Av. DBH (cm) | Av. Tree Age (a) | Leaf Area Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~500 | 1170 | 22 | 6.8 ± 1.19 | 7.5 ± 0.09 | 25 | 1.61 |

| ~1000 | 1180 | 29 | 9.7 ± 1.61 | 10.5 ± 0.31 | 26 | 1.78 |

| ~1500 | 1190 | 22 | 8.6 ± 1.06 | 13.9 ± 0.28 | 25 | 1.98 |

| ~2000 | 1180 | 23 | 9.5 ± 1.37 | 9.6 ± 0.55 | 22 | 2.74 |

| ~2500 | 1120 | 15 | 8.7 ± 1.63 | 9.6 ± 0.69 | 23 | 3.24 |

| ~3000 | 1120 | 26 | 7.8 ± 1.96 | 8.8 ± 0.65 | 23 | 3.91 |

| Soil Types | Stand Density (plants·hm−2) | Soil Depth (cm) | Soil Particle Size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand (%) (0.02~2 mm) | Silt (%) (0.002~0.02 mm) | Clay (%) (<0.002 mm) | |||

| Loessal soil | 500 | 20 | 90.34 | 9.66 | 0 |

| 40 | 93.06 | 6.94 | 0 | ||

| 60 | 91.75 | 8.25 | 0 | ||

| 80 | 92.37 | 7.63 | 0 | ||

| 100 | 90.81 | 9.19 | 0 | ||

| 1000 | 20 | 70.87 | 26.63 | 2.5 | |

| 40 | 74.08 | 25.4 | 0.52 | ||

| 60 | 73.25 | 25.95 | 0.8 | ||

| 80 | 74.87 | 24.58 | 0.55 | ||

| 100 | 73.35 | 24.08 | 2.57 | ||

| 1500 | 20 | 68.89 | 30.1 | 1.01 | |

| 40 | 68.66 | 29.3 | 2.04 | ||

| 60 | 67.29 | 30.73 | 1.98 | ||

| 80 | 69.77 | 27.35 | 2.88 | ||

| 100 | 69.62 | 27.82 | 2.56 | ||

| 2000 | 20 | 76.03 | 23.6 | 0.37 | |

| 40 | 79.76 | 19.89 | 0.35 | ||

| 60 | 75.49 | 24.13 | 0.38 | ||

| 80 | 79.9 | 19.74 | 0.36 | ||

| 100 | 78.63 | 20.84 | 0.53 | ||

| 2500 | 20 | 82.89 | 16.95 | 0.16 | |

| 40 | 80.14 | 19.69 | 0.17 | ||

| 60 | 84.66 | 15.17 | 0.17 | ||

| 80 | 83.71 | 16.12 | 0.17 | ||

| 100 | 83.16 | 16.67 | 0.17 | ||

| 3000 | 20 | 88.82 | 11.18 | 0 | |

| 40 | 89.1 | 10.9 | 0 | ||

| 60 | 85.2 | 14.8 | 0 | ||

| 80 | 86.51 | 13.49 | 0 | ||

| 100 | 87.38 | 12.62 | 0 | ||

| Indicators | Min. | Max. | Mean ± SE | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stand density (plants·hm−2) | 350 | 3400 | 1499 ± 53 | 1.06 | 1.48 |

| Soil total nitrogen (g·kg−1) | 0.06 | 2.63 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 2.25 | 6.04 |

| Soil total phosphorous (g·kg−1) | 0.03 | 1.99 | 0.56 ± 0.02 | 3.04 | 10.45 |

| Soil total potassium (g·kg−1) | 4.19 | 52.72 | 17.96 ± 0.64 | 1.06 | 1.48 |

| Soil CaCO3 (g·kg−1) | 13 | 94 | 45.6 ± 1.12 | 0.43 | 1.03 |

| Organic matter content (g·kg−1) | 1.31 | 55.60 | 9.79 ± 0.58 | 2.51 | 9.20 |

| Soil moisture content (%) | 5.66 | 33.97 | 11.54 ± 0.36 | 1.50 | 2.62 |

| Soil evaporation rate (g·D−1) | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 2.45 | 7.30 |

| Vegetation transpiration rate (g·D−1) | 0.43 | 1.93 | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 0.95 | 0.49 |

| Indicators | SD | Elevation | S | TH | DBH | Age | LAI | TN | TP | TK | CaCO3 | OMC | SMC | SER | VTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.337 ** | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.910 ** | 0.686 ** | 0.148 * | 0.243 ** | −0.710 ** | 0.761 ** |

| Elevation | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.248 ** | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 0.179 * | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.241 ** | −0.04 | −0.09 | 0.00 |

| S | 0.04 | 0.248 ** | 1.00 | −0.12 | 0.214 ** | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.10 | −0.08 | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| TH | 0.05 | 0.10 | −0.12 | 1.00 | −0.218 ** | 0.10 | −0.10 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.175 * | 0.02 | −0.167 * | −0.08 | 0.02 |

| DBH | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.214 ** | −0.218 ** | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.172 * | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.11 | −0.151 * | 0.287 ** | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| Age | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 1.00 | −0.14 | 0.07 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.170 * |

| LAI | 0.337 ** | −0.09 | −0.01 | −0.10 | 0.172 * | −0.14 | 1.00 | −0.11 | −0.08 | 0.337 ** | 0.201 ** | −0.07 | 0.338 ** | −0.314 ** | −0.11 |

| TN | −0.01 | 0.179 * | 0.01 | 0.14 | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.11 | 1.00 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.10 | 0.442 ** | −0.10 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| TP | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.14 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.08 | −0.02 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | −0.08 | 0.154 * |

| TK | 0.910 ** | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.337 ** | −0.01 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.686 ** | 0.148 * | 0.243 ** | −0.710 ** | −0.06 |

| CaCO3 | 0.686 ** | −0.08 | −0.06 | 0.175 * | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.201 ** | −0.10 | 0.11 | 0.686 ** | 1.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.774 ** | 0.10 |

| OMC | 0.148 * | 0.241 ** | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.151 * | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.442 ** | 0.11 | 0.148 * | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.09 | −0.14 | 0.07 |

| SMC | 0.243 ** | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.167 * | 0.287 ** | 0.03 | 0.338 ** | −0.10 | 0.12 | 0.243 ** | −0.01 | 0.09 | 1.00 | −0.11 | 0.10 |

| SER | −0.710 ** | −0.09 | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.14 | 0.02 | −0.314 ** | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.710 ** | −0.774 ** | −0.14 | −0.11 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| VTR | 0.761 ** | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.170 * | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.154 * | −0.06 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hou, G.; Bi, H.; Wang, N.; Cui, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhao, D.; Wang, S. Optimizing the Stand Density of Robinia pseudoacacia L. Forests of the Loess Plateau, China, Based on Response to Soil Water and Soil Nutrient. Forests 2019, 10, 663. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10080663

Hou G, Bi H, Wang N, Cui Y, Ma X, Zhao D, Wang S. Optimizing the Stand Density of Robinia pseudoacacia L. Forests of the Loess Plateau, China, Based on Response to Soil Water and Soil Nutrient. Forests. 2019; 10(8):663. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10080663

Chicago/Turabian StyleHou, Guirong, Huaxing Bi, Ning Wang, Yanhong Cui, Xiaozhi Ma, Danyang Zhao, and Shanshan Wang. 2019. "Optimizing the Stand Density of Robinia pseudoacacia L. Forests of the Loess Plateau, China, Based on Response to Soil Water and Soil Nutrient" Forests 10, no. 8: 663. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10080663

APA StyleHou, G., Bi, H., Wang, N., Cui, Y., Ma, X., Zhao, D., & Wang, S. (2019). Optimizing the Stand Density of Robinia pseudoacacia L. Forests of the Loess Plateau, China, Based on Response to Soil Water and Soil Nutrient. Forests, 10(8), 663. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10080663