The Forest Policies of ASEAN and Montréal Process: Comparing Highly and Weakly Formalized Regional Regimes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How does the institutional design of ASEAN and MP make them forest-related/focused regimes structurally?

- How do both regimes illustrate the adoption of coherent and consistent regional forest policies?

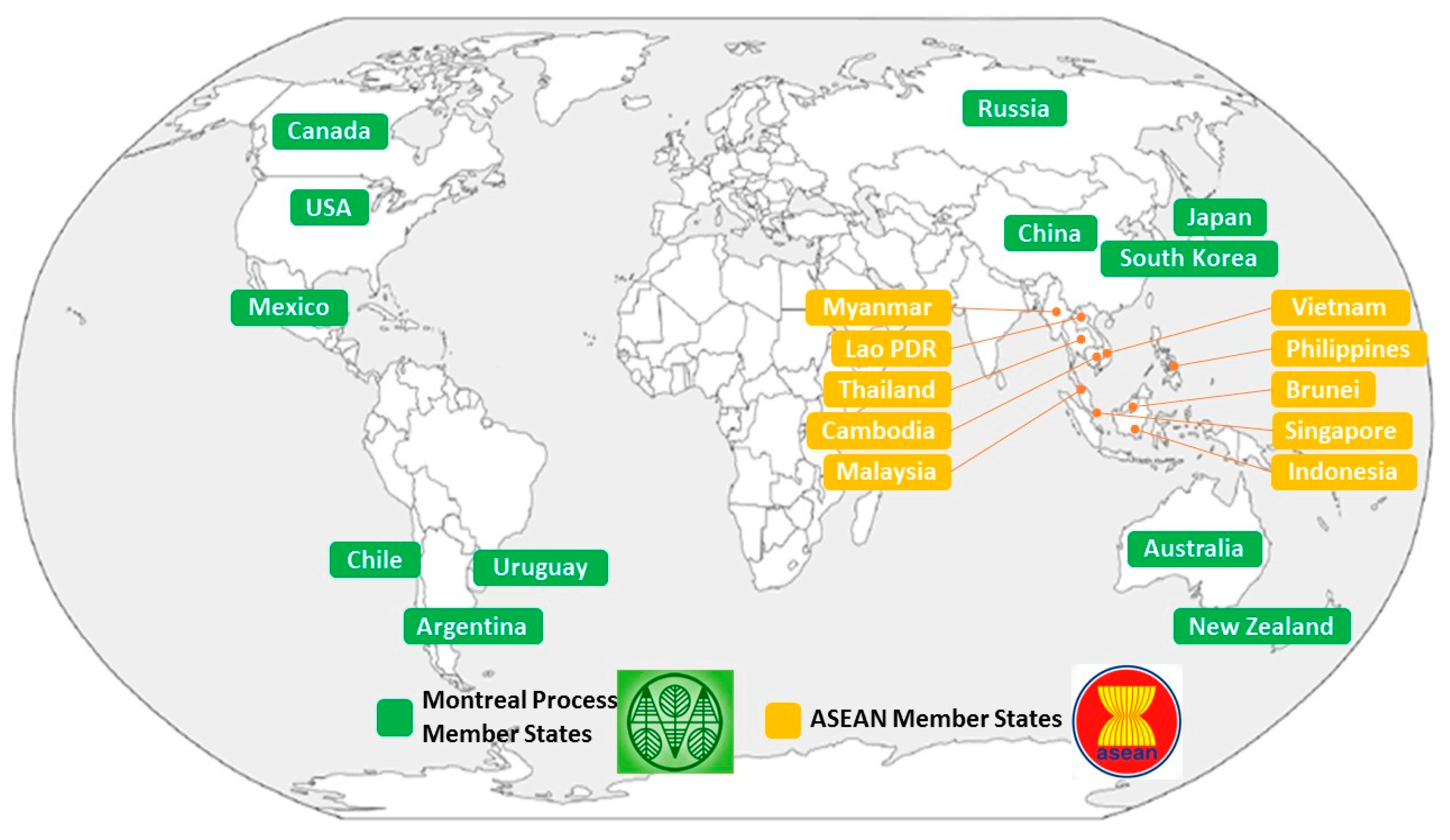

2. Context: The ASEAN and MP Forest Regimes

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. International and Regional Forest Regimes

3.2. Comparing Institutional Design

3.3. Comparative Study on Policy Development

4. Empirical Methods

5. Results

5.1. Institutional Design

5.1.1. ASEAN and MP Membership and Centralization Structures

5.1.2. Control Rules in ASEAN and MP Regimes

5.1.3. Flexibility of the ASEAN and MP Regimes

5.2. Policy Development of ASEAN and MP Regimes

6. Discussion

6.1. Comparing ASEAN and MP Forest Governance Design

6.2. Comparison between ASEAN and MP Forest Policy Development

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Nr. | Name of Forest Policy Projects and Programs | Amount (US$) | Funder | Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ASEAN-Wen Support Program | 1,000,000 | USAID | 2006–2016 |

| 2 | ASEAN-Swiss Partnership on Social Forestry and Climate Change Phase I, II | 224,383 | Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and AWG-SF Strategic Response Fund (ASRF) | 2012–2020 |

| 3 | Support for Ratification and the Implementation of the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing in ASEAN Countries | 300,000 | China | 2015–2016 |

| 4 | Protection of Biological Diversity in the ASEAN Member States in Cooperation with the ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity | 21,534,528 | BMZ, GIZ, KfW | 2015–2019 |

| 5 | Biodiversity Conservation and Management of Protected Areas in ASEAN | 11,333,962 | EU | 2016–2021 |

References

- Dimitrov, R.S. Hostage to norms: States, Institutions and global forest politics. Glob. Environ. Politics 2005, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, F.; Cadman, T. Whose norms prevail? Policy networks, international organizations and “sustainable forest management”. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2014, 27, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, B. Putting the national back into forest-related policies: The international forests regime and national policies in Brazil and Indonesia. Int. For. Rev. 2008, 10, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, C.L.; Cashore, B.; Kanowski, P. Global Environmental Forest Policies: An International Comparison; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; p. 392. [Google Scholar]

- Arts, B.; Babili, I. Global Forest Governance: Multiple Practices of Policy Performance. In Forest and Nature Governance; Arts, B., Behagel, J., van Bommel, S., de Koning, J., Turnhout, E., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 14, pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Giessen, L. Reviewing the main characteristics of the international forest regime complex and partial explanations for its fragmentation. Int. For. Rev. 2013, 15, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, D. Logjam: Deforestation and the Crisis of Global Governance; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, C.L.; Humphreys, D.; Wildburger, C.; Wood, P.; Marfo, E.; Pacheco, P.; Yasmi, Y. Mapping the core actors and issues defining international forest governance. In Embracing Complexity: Meeting the Challenges of International Forest Governance; Rayner, J., Buck, A., Katila, P., Eds.; IUFRO World Series 28; IUFRO: Vienna, Austria, 2010; pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, J.; Buck, A.; Katila, P. Embracing Complexity: Meeting the Challenges of International Forest Governance. A Global Assessment Report; Prepared by the Global Forest Panel on the International Forest Regime; IUFRO World Series; IUFRO: Vienna, Austria, 2010; Volume 28, p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, M.; Rayner, J.; Goehler, D.; Heidbreder, E.; Perron-Welch, F.; Rukundo, O.; Verkooijen, P.; Wildburger, C. Overcoming the challenges to integration. In Embracing Complexity: Meeting the Challenges of International Forest Governance; Rayner, J., Buck, A., Katila, P., Eds.; A Global Assessment Report; IUFRO World Series; IUFRO: Vienna, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Keohane, R.O.; Victor, D.G. The Regime Complex for Climate Change; The harvard project on international climate agreements; Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Keohane, R.O.; Victor, D.G. The regime complex for climate change. Perspect. Politics 2011, 9, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Blanco, C.R.; Burns, S.L.; Giessen, L. Mapping the fragmentation of the international forest regime complex: Institutional elements, conflicts and synergies. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2019, 19, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, B.J.M.; Appelstrand, M.; Kleinschmit, D.; Pülzl, H.; Visseren-Hamakers, I.J.; Atyi, R.E.; Yasmi, Y. Discourses, actors and instruments in international forest governance. In Embracing Complexity: Meeting the Challenges of International Forest Governance. A Global Assessment Report, Prepared by the Global Forest Expert Panel on the International Forest Regime; International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO): Vienna, Austria, 2010; pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cashore, B.; Stone, M.W. Can legality verification rescue global forest governance? Analyzing the potential of public and private policy intersection to ameliorate forest challenges in Southeast Asia. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 18, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giessen, L.; Sahide, M.A.K. Blocking, attracting, imposing, and aligning: The utility of ASEAN forest and environmental regime policies for strong member states. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurrochmat, D.R.; Dharmawan, A.H.; Obidzinski, K.; Dermawan, A.; Erbaugh, J.T. Contesting national and international forest regimes: Case of timber legality certification for community forests in Central Java, Indonesia. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 68, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahide, M.A.K.; Giessen, L. The fragmented land use administration in Indonesia–Analysing bureaucratic responsibilities influencing tropical rainforest transformation systems. Land Use Policy 2015, 43, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahide, M.A.K.; Maryudi, A.; Supratman, S.; Giessen, L. Is Indonesia utilising its international partners? The driving forces behind Forest Management Units. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 69, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkkey, H. Regional cooperation, patronage and the ASEAN Agreement on transboundary haze pollution. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2014, 14, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattberg, P. Transnational environmental regimes. In Global Environmental Governance Reconsidered; Frank, B., Pattberg, P.H., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Young, O.R. International regimes: Problems of concept formation. World Politics 1980, 32, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppell, J.G. World Rule: Accountability, Legitimacy, and the Design of Global Governance; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harrop, S.R.; Pritchard, D.J. A hard instrument goes soft: The implications of the Convention on Biological Diversity’s current trajectory. Global Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürging, J.; Giessen, L. Ein “Rechtsverbindliches Abkommen über die Wälder in Europa”: Stand und Perspektiven aus rechts-und umweltpolitikwissenschaftlicher Sicht. Nat. Recht 2013, 35, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Siebenhüner, B. Managers of Global Change: The Influence of International Environmental Bureaucracies; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Giessen, L. Forests and the two faces of international governance: Customizing international regimes through domestic politics. Edw. Elgar Ser. New Horiz. Environ. Politics 2019. accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, P.K.; Rahman, M.D.; Giessen, L. Regional governance by the South Asia Cooperative Environment Program (SACEP)? Institutional design and customizable regime policy offering flexible political options. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, P.K.; Rahman, M.D.; Giessen, L. Regional economic regimes and the environment: Stronger institutional design is weakening environmental policy capacity of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2019, 19, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, S.; Cashore, B. Complex global governance and domestic policies: four pathways of influence. Int. Affairs. 2012, 88, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundig, F. Dealing with the temporal domain of regime effectiveness: A further conceptual development of the Oslo-Potsdam solution. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2012, 12, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.; Howlett, M. Conclusion: Governance arrangements and policy capacity for policy integration. Policy Soc. 2009, 28, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stokke, O. (Ed.) Aid and Political Conditionality; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underdal, A. Meeting common environmental challenges: the co-evolution of policies and practices. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2013, 13, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACB. Protection of Biological Diversity in the ASEAN Member States in Cooperation with the ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity. 2019. Available online: https://aseanbiodiversity.org/key_programme/protection-of-biological-diversity-in-the-asean-member-states-in-cooperation-with-the-asean-centre-for-biodiversity-care4biodiv/ (accessed on 13 February 2019).

- Montreal Process. The Montréal Process Criteria and Indicators for the Conservation and Sustainable Management of Temperate and Boreal Forests. 2015. Available online: https://www.montrealprocess.org/documents/publications/techreports/MontrealProcessSeptember2015.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- ASEAN. ASEAN Cooperation in Food, Agriculture and Forestry Major Achievements. 2019. Available online: https://asean.org/?static_post=asean-cooperation-in-food-agriculture-and-forestry-major-achievements (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- WB (World Bank). GDP (Current US$). 2019. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). The Global Forest Resources Assessment. 2015. Available online: http://www.fao.org/forest-resources-assessment/past-assessments/fra-2015/en/ (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Heiduk, F. Indonesia in ASEAN: Regional Leadership between Ambition and Ambiguity; (SWP Research Paper, 6/2016); Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik -SWP- Deutsches Institut für Internationale Politik und Sicherheit: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-46859-8 (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- ASEAN. The ASEAN Declaration (Bangkok Declaration) Bangkok. 1967. Available online: https://asean.org/the-asean-declaration-bangkok-declaration-bangkok-8-august-1967/ (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- AMAF. Jakarta Consensus on Forestry. 1981. Available online: https://cil.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/formidable/18/1981-Jakarta-Consensus-on-ASEAN-Tropical-Forestry-pdf.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2019).

- Krell, G. Weltbilder und Weltordnung: Einführung in die Theorie der Internationalen Beziehungen, 4th ed.; Nomos: Baden, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sandholtz, W.; Sweet, A.S. European Integration and Supranational Governance; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfslehner, B.; Aggestam, F.; Hurmekoski, E.; Kulikova, E.; Lindner, M.; Nabuurs, G.J.; Hendriks, C.M.A. Study on Progress in Implementing the EU Forest Strategy-Evaluation Study; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krasner, S.D. Structural Causes and Regime Consequences: Regimes as Intervening Variables. Int. Organ. 1982, 36, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R. International regimes. In The Globalization of World Politics; Baylis, J., Smith, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 299–330. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra, J.C.; Sindt, J.; Giessen, L. The rational design of regional regimes: Contrasting Amazonian, Central African and Pan-European Forest Governance. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2018, 18, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemes, D. Regional Leadership in the Global System: Ideas, Interests and Strategies of Regional Powers; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmer, C.; Katzenstein, P.J. Why is there no NATO in Asia? Collective identity, regionalism, and the origins of multilateralism. Int. Organ. 2002, 56, 575–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetschke, A.; Lenz, T. Does regionalism diffuse? A new research agenda for the study of regional organizations. J. Eur. Public Policy 2013, 20, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giessen, L.; Sarker, P.; Rahman, M. International and domestic sustainable forest management policies: Distributive effects on power among state agencies in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2016, 8, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koremenos, B.; Lipson, C.; Snidal, D. The rational design of international institutions. Int. Organ. 2001, 55, 761–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kydd, A. Trust building, trust breaking: The dilemma of NATO enlargement. Int. Organ. 2001, 55, 801–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattli, W. Private justice in a global economy: From litigation to arbitration. Int. Organ. 2001, 55, 919–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Keilbach, P. Situation structure and institutional design: reciprocity, coercion, and Exchange. Int. Organ. 2001, 55, 891–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oatley, T.H. Multilateralizing trade and payments in postwar Europe. Int. Organ. 2001, 55, 949–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahre, R. Most-favored-nation clauses and clustered negotiations. Int. Organ. 2001, 55, 859–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendorff, B.P.; Milner, H.V. The optimal design of international trade institutions: uncertainty and escape. Int. Organ. 2001, 55, 829–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudeau, H.; Duplessis, I. Insights from global environmental governance. Int. Stud. Rev. 2013, 15, 562–589. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L.L.; Simmons, B.A. Theories and empirical studies of international institutions. Int. Organ. 1998, 52, 729–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.A.; Young, O.R.; Zürn, M. The study of international regimes. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 1995, 1, 267–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Rayner, J. Policy divergence as a response to weak international regimes: The formulation and implementation of natural resource new governance arrangements in Europe and Canada. Policy Soc. 2005, 24, 16–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Faur, D. The governance of international telecommunications competition: cross international study of international policy regimes. Compet. Chang. 1999, 4, 93–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberthur, S.; Tanzler, D. The influence of international regimes in policy diffusion: The Kyoto protocol and climate policies in the European Union. Z. Umweltpolit. Umweltr. 2006, 29, 283. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.A. Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comp. Politics 1993, 25, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashore, B.; Howlett, M. Punctuating which equilibrium? Understanding thermostatic policy dynamics in Pacific Northwest forestry. Am. J. Political Sci. 2007, 51, 532–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Cashore, B. Conceptualizing public policy. In Comparative Policy Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Krott, M. Forest Policy Analysis; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krott, M.; Bader, A.; Schusser, C.; Devkota, R.; Maryudi, A.; Giessen, L.; Aurenhammer, H. Actor-centred power: the driving force in decentralised community based forest governance. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 49, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glück, P.; Angelsen, A.; Appelstrand, M.; Assembe-Mvondo, S.; Auld, G.; Hogl, K.; Wildburger, C. Core Components of the International Forest Regime Complex; IUFRO (International Union of Forestry Research Organizations Secretariat): Vienna, Austria, 2010; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, M.; Mukherjee, I.; Woo, J.J. From tools to toolkits in policy design studies: The new design orientation towards policy formulation research. Policy Politics 2015, 43, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Ramesh, M.; Perl, A. Studying Public Policy: Policy Cycles and Policy Subsystems; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Vedung, E. Policy instrument: Typologies and theories. In Carrots, Sticks & Sermons Policy Instruments and Their Evaluation; Bemelmans-Videc, M.L., Rist, R.C., Vedung, E.O., Eds.; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 21–58. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, S.L.; Giessen, L. Dismantling comprehensive forest bureaucracies: Direct access, the World Bank, agricultural interests, and neoliberal administrative reform of forest policy in Argentina. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2016, 29, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuger, L.; Neuman, W.L. Social Work Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches: With Research Navigator; Pearson/Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.S.; Giessen, L. Mapping international forest-related issues and main actors’ positions in Bangladesh. Int. For. Rev. 2014, 16, 586–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Sarker, P.K.; Giessen, L. Power players in biodiversity policy: Insights from international and domestic forest biodiversity initiatives in Bangladesh from 1992 to 2013. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, P.K.; Rahman, M.D.; Giessen, L. Empowering state agencies through national and international community forestry policies in Bangladesh. Int. For. Rev. 2017, 19, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schusser, C.; Krott, M.; Devkota, R.; Maryudi, A.; Salla, M.; Yufanyi Movuh, M.C. Sequence design of quantitative and qualitative surveys for increasing efficiency in forest policy research. Allg. For. Jagdztg. (AFJZ) 2012, 183, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Schusser, C.; Krott, M.; Movuh, M.C.Y.; Logmani, J.; Devkota, R.R.; Maryudi, A.; Bach, N.D. Powerful stakeholders as drivers of community forestry—Results of an international study. Forest Policy Econ. 2015, 58, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahide, M.A.K.; Fisher, M.R.; Maryudi, A.; Dhiaulhaq, A.; Wulandari, C.; Kim, Y.-S.; Giessen, L. Deadlock opportunism in contesting conservation areas in Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, P.A.; Dayal, U. An overview of repository technology. VLDB 1994, 94, 705–713. [Google Scholar]

- Rahayu, S.; Laraswati, D.; Pratama, A.A.; Permadi, D.B.; Sahide, M.A.; Maryudi, A. Research trend: Hidden diamonds–The values and risks of online repository documents for forest policy and governance analysis. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 100, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansley, R.; Bass, M.; Stuve, D.; Branschofsky, M.; Chudnov, D.; McClellan, G.; Smith, M. The DSpace institutional digital repository system: Current functionality. In Proceedings of the 2003 Joint Conference on Digital Libraries, Houston, TX, USA, 27–31 May 2003; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Barton, M.; Bass, M.; Branschofsky, M.; McClellan, G.; Stuve, D.; Walker, J.H. DSpace: An Open Source Dynamic Digital Repository. D-Lib Magazine. 2003, Volume 9. Number 1. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/29465/D-Lib%20article%20January%202003.htm?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Kleinschmit, D.; Krott, M. The media in forestry: Government, governance and social visibility. In Public and Private in Natural Resource Governance: A False Dichotomy; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- GMA News Online. Papua New Guinea Asks RP Support for ASEAN Membership Bid. 2009. Available online: https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/news/nation/154860/papua-new-guinea-asks-rp-support-for-asean-membership-bid/story/ (accessed on 21 June 2019).

- Daily Express. Timor Leste Is Ready to Join ASEAN Grouping. 2015. Available online: http://www.dailyexpress.com.my/news.cfm?NewsID=98869 (accessed on 21 June 2019).

- Waybackmachine. Somare Seeks PGMA’s Support for PNG’s ASEAN Membership Bid. 2009. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20100306192700/http://www.op.gov.ph/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=22879&Itemid=2 (accessed on 21 June 2019).

- World Economic Forum. What Is ASEAN? 2019. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/05/what-is-asean-explainer/ (accessed on 12 May 2019).

- ASEAN Secretariat. The ASEAN Charter: 21th Reprint. 2017. Available online: https://asean.org/storage/2017/07/8.-July-2017-The-ASEAN-Charter-21th-Reprint-with-Updated-Annex-1.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Montreal Process. The Montréal Process Strategic Documents. In Proceedings of the 27th Montréal Process Working Group Meeting, Nelson, New Zealand, 13–17 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Montreal Process. Annex G: Working Group Meeting Report. In Proceedings of the 21st Montreal Process Working Group Meeting, Hilo, HI, USA, 1–4 June 2010; Available online: https://www.montrealprocess.org/Resources/Meeting_Reports/Working_Group/21_e.shtml (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- ASEAN. 2016–2025 Vision and Strategic Plan for ASEAN Cooperation in Food, Agriculture, and Forestry. 2015. Available online: https://cil.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/formidable/18/2016-2025-Vision-and-Stgc-Plan-ASEAN-Coop-in-Food-Agri-Forestry.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- AWG-SF. History. 2019. Available online: http://www.awg-sf.org/ (accessed on 21 June 2019).

- ASEAN Investment Report. In Foreign Direct Investment and the Digital Economy in ASEAN Jakarta; ASEAN Secretariat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2018.

- Merced, L.D.C. Partners for Change Understanding the External Relations of ASEAN; Foreign Service Institute: Arlington, VA, USA, 2017. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11540/7440 (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Montreal Process. Annex F: Working Group Meeting Report. In Proceedings of the 21st Montreal Process Working Group Meeting, Hilo, HI, USA, 1–4 June 2010; Available online: https://www.montrealprocess.org/Resources/Meeting_Reports/Working_Group/21_e.shtml (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- Montreal Process. Annex H: Working Group Meeting Report. In Proceedings of the 21st Montreal Process Working Group Meeting, Hilo, HI, USA, 1–4 June 2010; Available online: https://www.montrealprocess.org/Resources/Meeting_Reports/Working_Group/21_e.shtml (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- ASEAN. Agreement for the Establishment of a Fund for ASEAN Rules Governing the Control, Disbursement and Accounting of the Fund for the ASEAN Cameron Highlands. 1969. Available online: https://asean.org/?static_post=asean-secretariat-basic-documents-agreement-for-the-establishment-of-a-fund-for-asean-rules-governing-the-control-disbursement-and-accounting-of-the-fund-for-asean-cameron-highlands-17-december-1969-2 (accessed on 12 May 2019).

- ASEAN. Agreement on the Establishment of the ASEAN Development Fund Vientiane. 26 July 2005. Available online: https://asean.org/?static_post=agreement-on-the-establishment-of-the-asean-development-fund-vientiane-26-july-2005-2 (accessed on 12 May 2019).

- ASEAN. Strategic Plan of Action for ASEAN Cooperation on Forestry (2016–2025) 2016. Available online: https://asean.org/storage/2016/10/Strategic-Plan-of-Action-for-ASEAN-Cooperation-on-Forestry-2016-2025.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Yoshimatsu, H. International Regimes, International Society, and Theoretical Relations. Int. Stud. 1991, 17, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Montreal Process. Working Group Meeting Report. In Proceedings of the 2nd Meeting of the Working Group, Delhi, India, 28 July 1994; Available online: https://www.montrealprocess.org/Resources/Meeting_Reports/Working_Group/2_e.shtml (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Kahler, M. Institution-building in the Pacific; Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies, University of California: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993; Volume 93. [Google Scholar]

- EU (European Union). Enlargement and Stabilisation and Association Process; Document no. 16991/14; General Secretariat of the Council: Brussels, Belgium, 16 December 2014; Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/enlargement/ (accessed on 12 January 2019).

- Linser, S.; Wolfslehner, B.; Bridge, S.; Gritten, D.; Johnson, S.; Payn, T.; Robertson, G. 25 Years of Criteria and Indicators for Sustainable Forest Management: How Intergovernmental C&I Processes Have Made a Difference. Forests 2018, 9, 578. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, C.L.; O’Carroll, A.; Wood, P. International Forest Policy–the Instruments, Agreements and Processes that Shape It; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations Forum on Forests (UNFF) Secretariat: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Willetts, P. Transnational actors and international organizations in global politics. In The Globalisation of World Politics, 2nd ed.; Baylis, J.B., Smith, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 356–383. [Google Scholar]

- Montreal Process Joint statement of The Montréal Process, International Tropical Timber Organization, FOREST EUROPE, and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ Global Forest Resources Assessment. 5 January 2012. Available online: https://www.montrealprocess.org/Resources/Official_Statements/index.shtml (accessed on 25 January 2019).

- Chandran, A.; Innes, J.L. The state of the forest: Reporting and communicating the state of forests by Montreal Process countries. Int. For. Rev. 2014, 16, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, K.M.; Höck, B.K.; Spence, H.R.; Crawford, K.A.; Payn, T.W.; Barnard, T.D. New Zealand school children’s perceptions of local forests and the Montréal Process Criteria and Indicators: Comparing local and international value systems. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 2015, 45, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcginley, K.A.; Cubbage, F.W. Examining Forest Governance in the United States Through the Montréal Process Criteria and Indicators Framework. Int. For. Rev. 2017, 19, 192–208. [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, F.; Bauer, S. Managers of Global Governance. Assessing and Explaining the Influence of International Bureaucracies; Global Governance Working Paper; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ASEAN. The ASEAN Secretariat: Basic Mandate, Functions and Composition. 2012. Available online: https://asean.org/?static_post=asean-secretariat-basic-documents-asean-secretariat-basic-mandate-2 (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- Tarasofsky, R.G. Assessing the International Forest Regime; IUCN Environmental Policy and Law Paper No. 37; International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources: Gland, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- De Wet, E. The international constitutional order. Int. Comp. Law Q. 2006, 55, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, T.; Woon, W.; Tan, A.; Sze-Wei, C. Charter makes ASEAN stronger, more united and effective. Straits Times, 8 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sukma, R. ASEAN beyond 2015: The Imperatives for Further Institutional Changes; ERIA Discussion Paper Series; ERIA Annex Office: Jakarta Pusat, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Montreal Process. Regional and Sub-Regional Inputs to UNFF11. 2014. Liaison Officer of the Montréal Process Working Group, Japan. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=7&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiagIuqwKXiAhXD-qQKHQ-wATEQFjAGegQIBxAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.un.org%2Fesa%2Fforests%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F06%2FMontreal-Process.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0ssL7M_7iHar_msKJI9Ac4 (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Montreal Process Annex E. 2009. Available online: https://www.montrealprocess.org/documents/meetings/working/an-5.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Young, O.R. International Governance: Protecting the Environment in a Stateless Society; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- ASEAN. ASEAN Criteria and Indicators for Sustainable Management of Tropical Forests. 2017. Available online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/21.-ASEAN-CI-for-SFM.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- UNFF. ASEAN inputs to the eleventh session of the United Nations Forum on Forest (UNFF) 2014. In Forests: Progress, Challenges and the Way Forward on the International Arrangement on Forests (IAF); ASEAN Secretariat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, B.G. Policy instruments and policy capacity. In Challenges to State Policy Capacity; Painter, M., Pierre, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon, L.M. Handbook of Policy Instruments; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Oberthür, S.; Gehring, T. (Eds.) Institutional Interaction in Global Environmental Governance: Synergy and Conflict Among International and EU Policies; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hafner, G. Pros and cons ensuing from fragmentation of international law. Mich. J. Int. L. 2003, 25, 849. [Google Scholar]

- Briassoulis, H. Complex environment problems and the quest of policy integration. In Policy Integration for Complex Environmental Problems: The Example of Mediterranean Desertification; Briassoulis, H., Ed.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Böcher, M.; Töller, A.E. Conditions for the emergence of alternative environmental policy instruments. In Proceedings of the 2nd ECPR-Conference, Marburg, Germany, 18–21 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Majone, G. Choice among policy instruments for pollution control. Policy Anal. 1976, 2, 589–613. [Google Scholar]

- Thang, H.C. Managing regional expert pools through regional knowledge networks in ASEAN. In Seminar Proceedings ASEAN High-Level Seminar. Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation: Towards a Cross-Sectoral Programme Approach in ASEAN; Van Wart, M., Goehler, D., Fawzia, F., Eds.; ASEAN: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Strutt, A.; Hertel, T.W.; Stone, S. Chapter 8 Exploring Poverty Impacts of ASEAN Trade Liberalization for Cambodia, Lao PDR, Thailand and Vietnam. In New Developments in Computable General Equilibrium Analysis for Trade Policy; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2010; pp. 217–245. [Google Scholar]

- Solaymani, S.; Shokrinia, M. Economic and environmental effects of trade liberalization in Malaysia. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 2016, 18, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones, R.M. Regional Cooperation for Food Security: The Case of Emergency Rice Reserves in the ASEAN Plus Three; ADB Sustainable Development Working Paper Series Publication Stock No. WPS114120; ADB: Metro Manila, Philippines, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Attributes |

|---|---|

| Membership rules (Membership) | Membership pattern might be either restrictive or exclusive. Regional states may be the only members or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) may be allowed. Additionally, a state dominant over other states for a long period of time acts as a hegemon |

| Scope of issues covered (Scope) | Institution is established to address one or several specific issues. Issues might have a wide range of coverage and change continuously over time |

| Centralization of tasks (Centralization) | Centralization revolves around the administrative performance of institutional tasks; it focuses mainly on dissemination of information, bargaining and transaction cost reduction, and the enhancement of enforcement |

| Rules for controlling the institution (Control) | Voting and financing of the institution are the key elements for determining control. Other elements include whether all members have equal votes; a minority holds veto power; and decisions are made through a simple majority, a supermajority, or unanimity |

| Flexibility of arrangements (Flexibility) | Flexibility is the way institutions deal with new situations and can be of two types: adaptive (e.g., an escape clause in a treaty) or transformative (i.e., built-in arrangements or reactions to shocking events) |

| Criterion | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Policy goals, aims or ends (general types of ideas that govern policy development) | The goals are mentioned explicitly in the regime’s forest policy |

| The goals are coherent, i.e., non-conflicting with each other (nor necessarily reinforcing), e.g., simultaneously promoting in situ biodiversity conservation and the conversion of natural forests to other uses | |

| Policy instruments (policy implementation preferences) | The policy means chosen/proposed to achieve the goals are consistent with each other, e.g., projects, conventions, agreements, declarations, principles, statements, decisions, resolutions, annual reports, publications |

| Precise settings of policy instruments | Specific types of instrument are utilized in the regime’s climate policy |

| Regulatory instruments | |

| Sanction/control mechanisms, secretariat mandates with reinforcement | |

| Incentive instruments | |

| e.g., stable core funding, substantial projects funding, disincentives (e.g., fines for illegal logging, taxes, fees) | |

| Informational instruments | |

| Numerical indicators exist (e.g., 15% forest area increase), issue-specific periodic reports issued within the regime, producing substantial public relation and outreach materials |

| ASEAN | MP |

|---|---|

| Secretariat operational cost: | Liaison Office operational cost: |

| Equal contribution of US$1 million | Baseline funding from a host country Supplementary support from the other MP member states (in case of need) |

| ASEAN development fund: | Budgeted funds: |

| Equal contribution of US$1.1 million | MP Working Group fund to assist MP Liaison Office and MP Technical Advisory Committee |

| Common pool of financial resources to support the implementation of its action plan | Voluntary contribution |

| Intra-ASEAN investment: | Individual country funding: |

| Financial investment by internal audits | Participation costs for MP Working Group and MP Technical Advisory Committee meetings |

| Foreign direct investment: | Financial support among member states: |

| Financial investment by external audits Majority of dialogue and development partners | Aid for an MP member state which cannot afford to participate in meetings |

| Policy Component | ASEAN | Montréal Process |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Plan of Action for ASEAN Cooperation on Forestry (2016–2025) | Conceptual Framework for the Montréal Process Strategic Action Plan (2009–2015) | |

| Policy goals |

|

|

| Policy instruments |

|

|

| Precise setting of policy instruments | Regulatory:

| Regulatory:

|

Incentives:

| Incentives:

| |

Information:

| Information:

|

| Significant Observation | Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) | The Montreal Process (MP) |

|---|---|---|

| Regime type | Treaty based forest-related regime due to non-primary issue as forests but significant for forests | Non-treaty-based forest-focused regime due to primary issue as forests |

| Membership rules | Exclusive and restrictive by design and followed by the constitution | Inclusive and voluntarily by design |

| Decision-making process | Unanimity and highly political | Not clearly mentioned but super flexible |

| Centralization of tasks | Summit composed of the heads of the member states | Working Group consists of voluntarily selected forest officials from the member states |

| Secretariat office | Permanently located at one of the member states, i.e., Indonesia | Willingness of member states for hosting, i.e., sporadically move when needs |

| Operational cost | Equal amount of financial contribution from member states | Low cost beliefs with need-based contribution |

| Synergic on forest issues | All relevant forest issues (e.g., deforestation and forest degradation, biodiversity, timber certification, greenhouse gas emission) condensed under the broader label of sustainable forest management (SFM) | |

| Forest policy goals | Goals are mentioned explicitly and coherent each other | |

| Policy instruments (policy implementation preferences) | The chosen/proposed tools are consistent with each other | |

| Precise settings of policy instruments | Highly importance for both regulatory and incentive instruments | Informational instruments are high priority |

| Synergistic overlaps on SFM criterion and indicators (C&Is) | Both regimes work on the same meaning of seven SFM criterion | |

| Political will on forests | Establishing/maintaining development cooperation nationally, regionally, and globally for hunting external financial resources | Maintaining strong networking systems for getting global recognition through aligning the SFM C&Is with other regional and global institutions |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeon, S.; Sarker, P.K.; Giessen, L. The Forest Policies of ASEAN and Montréal Process: Comparing Highly and Weakly Formalized Regional Regimes. Forests 2019, 10, 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10100929

Jeon S, Sarker PK, Giessen L. The Forest Policies of ASEAN and Montréal Process: Comparing Highly and Weakly Formalized Regional Regimes. Forests. 2019; 10(10):929. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10100929

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeon, Sohui, Pradip Kumar Sarker, and Lukas Giessen. 2019. "The Forest Policies of ASEAN and Montréal Process: Comparing Highly and Weakly Formalized Regional Regimes" Forests 10, no. 10: 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10100929

APA StyleJeon, S., Sarker, P. K., & Giessen, L. (2019). The Forest Policies of ASEAN and Montréal Process: Comparing Highly and Weakly Formalized Regional Regimes. Forests, 10(10), 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10100929