A Multifocal RSSeg Approach for Skeletal Age Estimation in an Indian Medicolegal Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A novel Indian dataset of wrist, elbow, shoulder, and pelvis X-rays highlights the population’s specific skeletal features, curated in accordance with ethical guidelines;

- A region-based symbolic segmentation (RSSeg) hierarchical patch-processing segmentation preserves soft-tissue cues to accurately retain ossification centers across multiple joints at an early stage;

- A classification model focuses on extracting anatomical cues from the segmented region, enhancing robustness, reliability, and generalizability for suitable medicolegal age estimation.

2. Related Work

3. Proposed Methodology

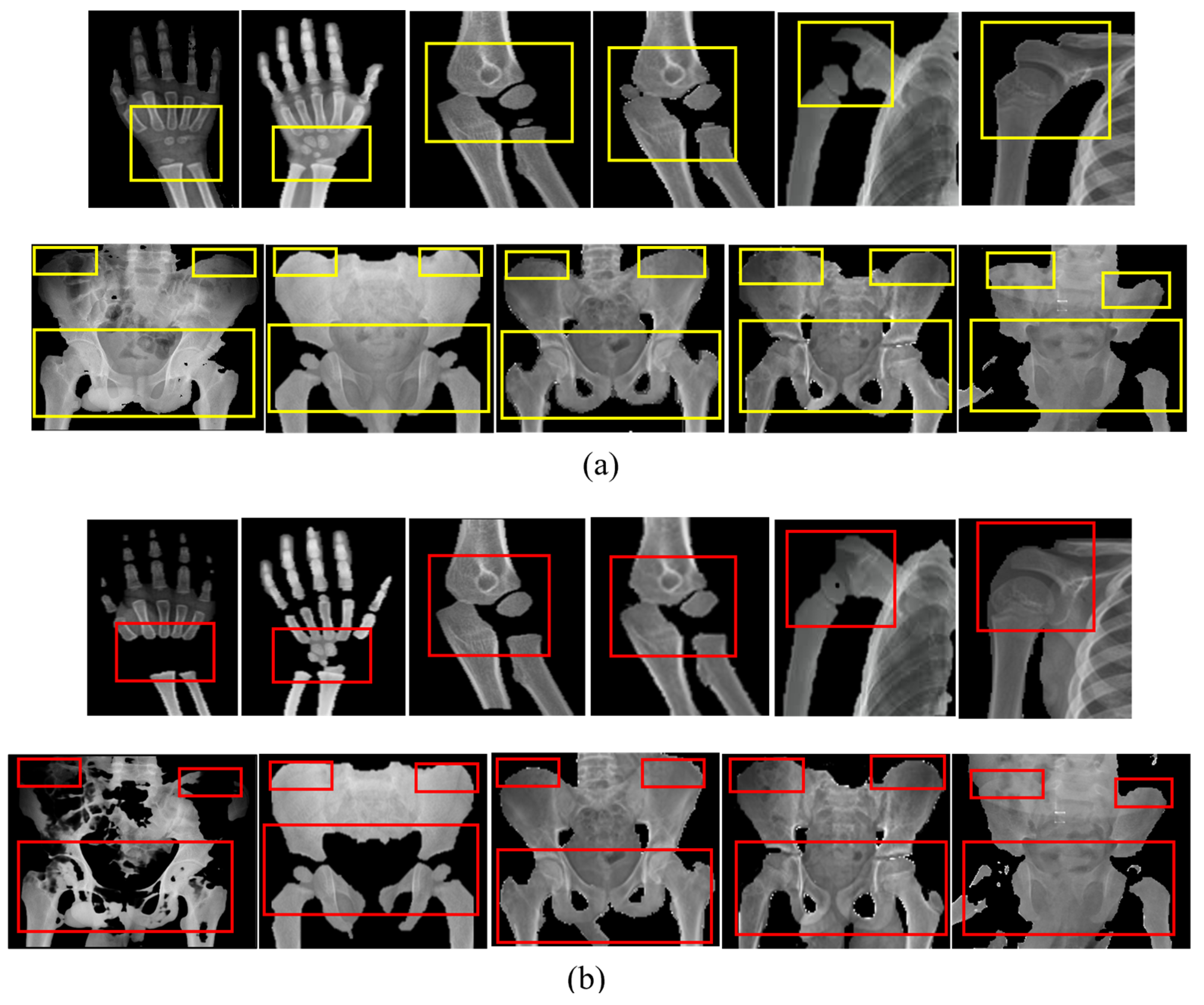

3.1. Preprocessing

3.2. Region-Based Symbolic Segmentation

4. Experimentation and Result

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Evaluation Metric

4.3. Experimental Setup

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RSSeg | region-based symbolic segmentation |

| ROI | region of interest |

| RSNA | Radiological Society of North America |

| DHA | Digital Hand Atlas |

| CLAHE | Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization |

| CDF | Cumulative Distribution Function |

| patch | |

| entropy | |

| sub-patch | |

| background | |

| foreground | |

| mean-intensity threshold | |

| standard deviation | |

| class representative | |

| acceptance count | |

| IMIT | Indian Medicolegal Infant-Toddler |

| IMC | Indian Medicolegal Child |

| IMPA | Indian Medicolegal Pre-Adolescent |

| IMPT | Indian Medicolegal Pre-Teen |

| IMT | Indian Medicolegal Teen |

| IMYA | Indian Medicolegal Young Adult |

| IMA | Indian Medicolegal Adult |

| CRITOE | capitellum, radius, internal epicondyle, trochlea, olecranon, external epicondyle |

References

- Bhardwaj, V.; Kumar, I.; Aggarwal, P.; Singh, P.K.; Shukla, R.C.; Verma, A. Demystifying the Radiography of Age Estimation in Criminal Jurisprudence: A Pictorial Review. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 2024, 34, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.N. The Essentials of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, 34th ed.; Jaypee Brothers Medical Publisher (P), Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2017; p. 501. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, M.D.; Novotny, R.; Bilezikian, J.P.; Weaver, C.M. Race and Diet Interactions in the Acquisition, Maintenance, and Loss of Bone12. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 1256S–1260S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, A.; Prentice, A.; Ward, K.A. Ethnic differences in bone health. Front. Endocrinol. 2015, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, O.; Shevroja, E.; Dhamo, B.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Wolvius, E.B.; Rivadeneira, F.; Medina-Gomez, C. Skeletal maturation in relation to ethnic background in children of school age: The Generation R Study. Bone 2020, 132, 115180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.D.; Wit, J.M.; Hochberg, Z.E.; Sävendahl, L.; Van Rijn, R.R.; Fricke, O.; Cameron, N.; Caliebe, J.; Hertel, T.; Kiepe, D.; et al. The use of bone age in clinical practice—Part 1. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2011, 76, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Oh, Y.J.; Shin, J.Y.; Rhie, Y.J.; Lee, K.H. Comparison of the Greulich-Pyle and Tanner Whitehouse (TW3) Methods in Bone Age Assessment. J. Korean Soc. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2008, 13, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Wei, D.; Zhao, C.; Wei, Z. Fully Automated Bone Age Assessment on Large-Scale Hand X-Ray Dataset. Int. J. Biomed. Imaging 2020, 2020, 8460493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, A.; Mursanto, P. Multi region-based feature connected layer (RB-FCL) of deep learning models for bone age assessment. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liu, S. Automatic feature extraction in X-ray image based on deep learning approach for determination of bone age. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 110, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, Y.; Darshan, D.; Sahanashree, K.J.; Nagamani, P.N.; Satish, B.B. BoneSegNet: Enhanced 2D-TransUnet Model for Multiclass Semantic Segmentation of X-Ray Images of Human Hand Bone. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE North Karnataka Subsection Flagship International Conference (NKCon), Bagalkote, India, 21–22 September 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Tian, M.; Li, B. Accurate instance segmentation in Pediatric elbow radiographs. Sensors 2021, 21, 7966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Salhi, A.; Fadhel, M.A.; Bai, J.; Hollman, F.; Italia, K.; Pareyon, R.; Albahri, A.S.; Ouyang, C.; Santamaría, J.; et al. Trustworthy deep learning framework for the detection of abnormalities in X-ray shoulder images. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, S.; Bingol, O.; Coskuncay, A.; Aydin, T. The impact of implementing backbone architectures on fracture segmentation in X-ray images. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2024, 59, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinsoy, H.B.; Gurses, M.S.; Bogan, M.; Unlu, N.E. Applicability of 3.0 T MRI images in the estimation of full age based on shoulder joint ossification: Single-centre study. Leg. Med. 2020, 47, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.G.; Cao, Y.J.; Zhao, Y.H.; Zhou, X.J.; Huang, B.; Zhang, G.C.; Huang, P.; Wang, Y.H.; Ma, K.J.; Chen, F.; et al. Sex Estimation of Medial Aspect of the Ischiopubic Ramus in Adults Based on Deep Learning. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi 2023, 39, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Z.; Dong, X.; Liang, W.; Xue, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Z. Forensic age estimation for pelvic X-ray images using deep learning. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 29, 2322–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JLee, J.M.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, K.G. Deep-learning-based pelvic automatic segmentation in pelvic fractures. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhu, T.; Xu, X. Bone age assessment based on deep convolution neural network incorporated with segmentation. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2020, 15, 1951–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, M.; Bai, X.; Zhou, F. Bone age assessment based on rank-monotonicity enhanced ranking CNN. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 120976–120983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifley, M.A.; Abdani, S.R.; Zulkifley, N.H. Automated bone age assessment with image registration using hand X-ray images. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, G. Skeletal bone age prediction based on a deep residual network with spatial transformer. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 197, 105754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y. Bone age assessment with X-ray images based on contourlet motivated deep convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 20th International Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing (MMSP), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 29–31 August 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.; Khaparde, A. Faster region-convolutional neural network oriented feature learning with optimal trained recurrent neural network for bone age assessment for pediatrics. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2022, 71, 103016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.Y.; Wee, L.K.; Swee, T.T.; Salleh, S.H. Adaptive crossed reconstructed (acr) k-mean clustering segmentation for computer-aided bone age assessment system. Int. J. Math. Models Methods Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 628–635. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Qi, J.; Liu, Z.; Ning, Q.; Luo, X. Automatic bone age assessment based on intelligent algorithms and comparison with TW3 method. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2008, 32, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeshina, S.A.; Lindner, C.; Cootes, T.F. Automatic segmentation of carpal area bones with random forest regression voting for estimating skeletal maturity in infants. In Proceedings of the 2014 11th International Conference on Electronics, Computer and Computation (ICECCO), Abuja, Nigeria, 29 September 2014–1 October 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, P.; Moura, D.C.; Guevara López, M.A.; Guerra, C.; Pinto, D.; Ramos, I. Impact of ensemble learning in the assessment of skeletal maturity. J. Med. Syst. 2014, 38, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, D.; Spampinato, C.; Scarciofalo, G.; Leonardi, R. An automatic system for skeletal bone age measurement by robust processing of carpal and epiphysial/metaphysial bones. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2010, 59, 2539–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.; Khaparde, A. Multi-objective segmentation approach for bone age assessment using parameter tuning-based U-net architecture. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 6755–6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, I.; Hamza, A.B. Ridge regression neural network for pediatric bone age assessment. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 30461–30478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajitha, B.; Agarwal, S. Segmentation of Epiphysis Region-of-Interest (EROI) using texture analysis and clustering method for hand bone age assessment. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 1029–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Han, J.; Jia, Y.; Fan, L.; Gou, F. Versatile framework for medical image processing and analysis with application to automatic bone age assessment. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2018, 2018, 2187247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Men, P.; Guo, H.; An, J. Region-based two-stage MRI bone tissue segmentation of the knee joint. IET Image Process. 2022, 16, 3458–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guru, D.S.; Vinay Kumar, N. Symbolic representation and classification of logos. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision and Image Processing: CVIP 2016, Roorkee, India, 26–28 February 2016; Springer: Singapore, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, M.; Sreekumar, S.; Arsh, S. Detection of COVID-19 from the chest X-ray images: A comparison study between CNN and ResNet-50. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 2nd Mysore Sub Section International Conference (MysuruCon), Mysuru, India, 16–17 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, C.; Gedik, M.A.; Kaya, Y. Age Estimation from Left-Hand Radiographs with Deep Learning Methods. Trait. Du Signal 2021, 38, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Classes | Class Label | Class Interval (in Years) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | IMIT | >0.1 to ≤4 |

| 2 | IMC | >4 to ≤7 |

| 3 | IMPA | >7 to ≤12 |

| 4 | IMPT | >12 to ≤14 |

| 5 | IMT | >14 to ≤18 |

| 6 | IMYA | >18 to ≤21 |

| 7 | IMA | >21 |

| Ossification Joints | IMIT | IMC | IMPA | IMPT | IMT | IMYA | IMA | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wrist | 171 | 135 | 290 | 180 | 228 | 202 | 150 | 1356 |

| Elbow | 168 | 150 | 230 | 169 | 205 | 158 | 148 | 1228 |

| Shoulder | 284 | 241 | 198 | 256 | 193 | 169 | 165 | 1506 |

| Pelvis | 98 | 104 | 161 | 212 | 76 | 146 | 183 | 980 |

| Segmentation Models | Wrist (%) | Elbow (%) | Shoulder (%) | Pelvis (%) | Overall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net | 88.5 ± 0.50 | 85.5 ± 0.51 | 88.5 ± 0.12 | 80.3 ± 0.27 | 85.7 ± 0.35 |

| Attention U-Net | 89.4 ± 0.89 | 88.5 ± 0.54 | 89.9 ± 0.10 | 84.9 ± 0.25 | 88.2 ± 0.45 |

| TransU-Net | 91.3 ± 0.90 | 89.2 ± 0.51 | 90.9 ± 0.11 | 85.9 ± 0.56 | 89.3 ± 0.53 |

| DeepLabV3+ | 91.9 ± 0.06 | 89.6 ± 0.48 | 91.3 ± 0.15 | 86.9 ± 0.35 | 89.9 ± 0.26 |

| Adaptive Otsu | 86.5 | 77.8 | 91.6 | 77.4 | 83.3 |

| Watershed | 91.1 | 76.5 | 92.1 | 76.3 | 84.0 |

| Proposed RSSeg | 92.1 | 93.7 | 89.9 | 90.3 | 91.5 |

| Segmentation Method | Jaccard Similarity (%) | Dice Coefficient (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | Pixel Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net | 80.1 ± 0.42 | 79.2 ± 0.38 | 86.5 ± 0.35 | 86.0 ± 0.40 | 85.7 ± 0.35 |

| Attention U-Net | 81.2 ± 0.12 | 79.9 ± 0.53 | 85.9 ± 0.22 | 87.1 ± 0.17 | 88.2 ± 0.45 |

| TransU-Net | 83.1 ± 0.13 | 78.2 ± 0.14 | 81.5 ± 0.27 | 88.8 ± 0.09 | 89.3 ± 0.53 |

| DeepLabV3+ | 83.4 ± 0.30 | 80.9 ± 0.28 | 87.0 ± 0.21 | 89.2 ± 0.40 | 89.9 ± 0.26 |

| Adaptive Otsu | 82.3 | 77.3 | 85.0 | 84.2 | 83.3 |

| Watershed | 81.9 | 79.5 | 83.2 | 86.0 | 84.0 |

| Proposed RSSeg | 84.5 | 81.4 | 88.3 | 90.0 | 91.5 |

| Metric | DeepLabV3+ (%) | Proposed RSSeg (%) | Mean Difference (%) | Paired Test Significance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jaccard Similarity | 83.4 ± 0.30 | 84.5 | 1.1 | p < 0.05 |

| Dice Coefficient | 80.9 ± 0.28 | 81.4 | 0.5 | p < 0.05 |

| Precision | 87.0 ± 0.21 | 88.3 | 1.3 | p < 0.05 |

| Recall | 89.2 ± 0.40 | 90.0 | 0.8 | p < 0.05 |

| Pixel Accuracy | 89.9 ± 0.26 | 91.5 | 1.6 | p < 0.05 |

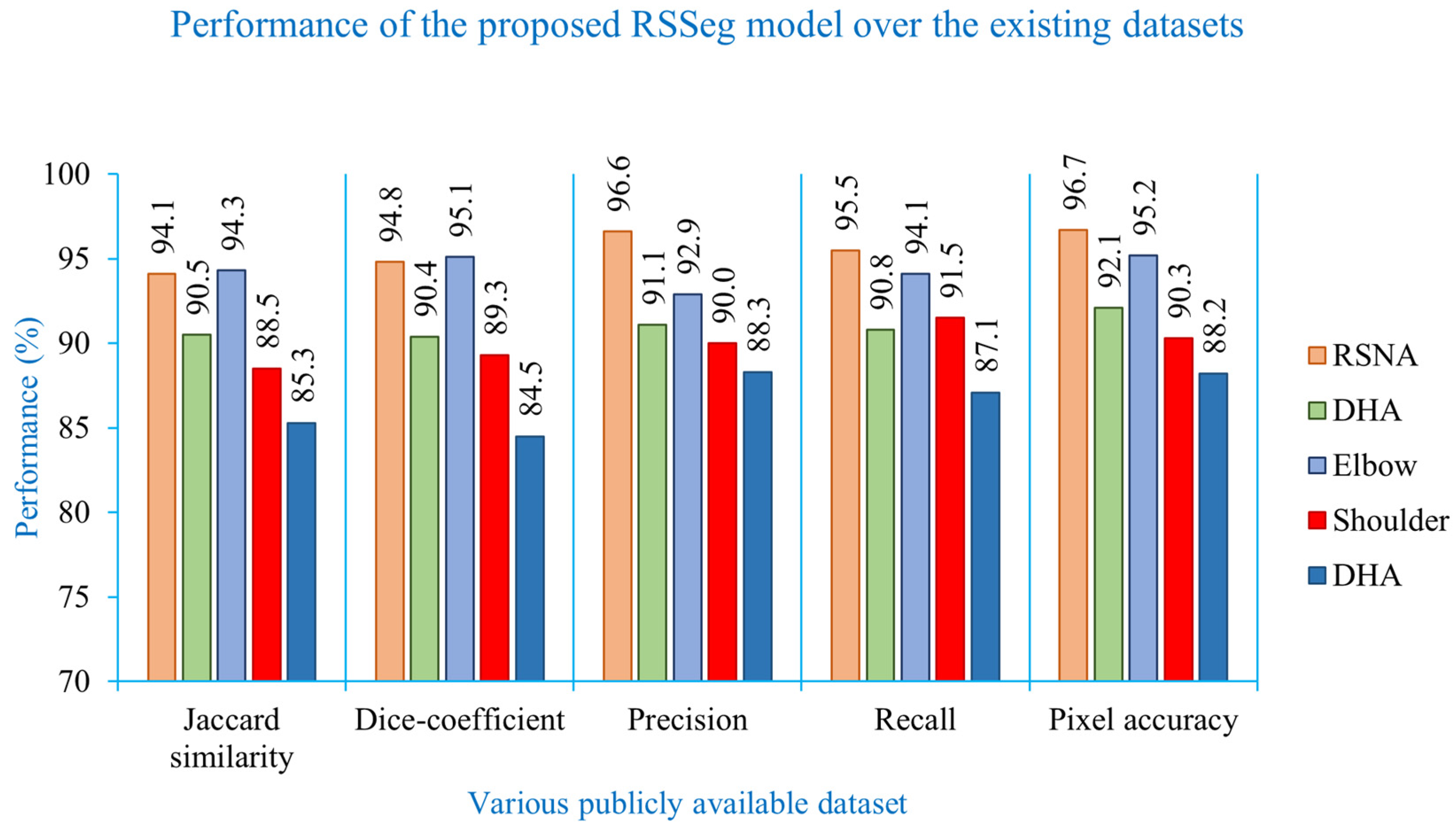

| Dataset | Jaccard Similarity (%) | Dice Coefficient (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | Pixel Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSNA [8] | 94.1 | 94.8 | 96.6 | 95.5 | 96.7 |

| DHA [9] | 90.5 | 90.4 | 91.1 | 90.8 | 92.1 |

| Elbow [12] | 94.3 | 95.1 | 92.9 | 94.1 | 95.2 |

| Shoulder [10] | 88.5 | 89.3 | 90.0 | 91.5 | 90.3 |

| Pelvis [15] | 85.3 | 84.5 | 88.3 | 87.1 | 88.2 |

| Ossification Joints | Total Samples | Training | Validation | Testing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 70 | 80 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 20 | 15 | 10 | ||

| Wrist | 1356 | 814 | 949 | 1084 | 271 | 203 | 136 | 271 | 204 | 136 |

| Elbow | 1228 | 737 | 860 | 982 | 245 | 184 | 123 | 246 | 184 | 123 |

| Shoulder | 1506 | 904 | 1054 | 1204 | 301 | 226 | 151 | 301 | 226 | 151 |

| Pelvis | 980 | 588 | 686 | 784 | 196 | 147 | 98 | 196 | 147 | 98 |

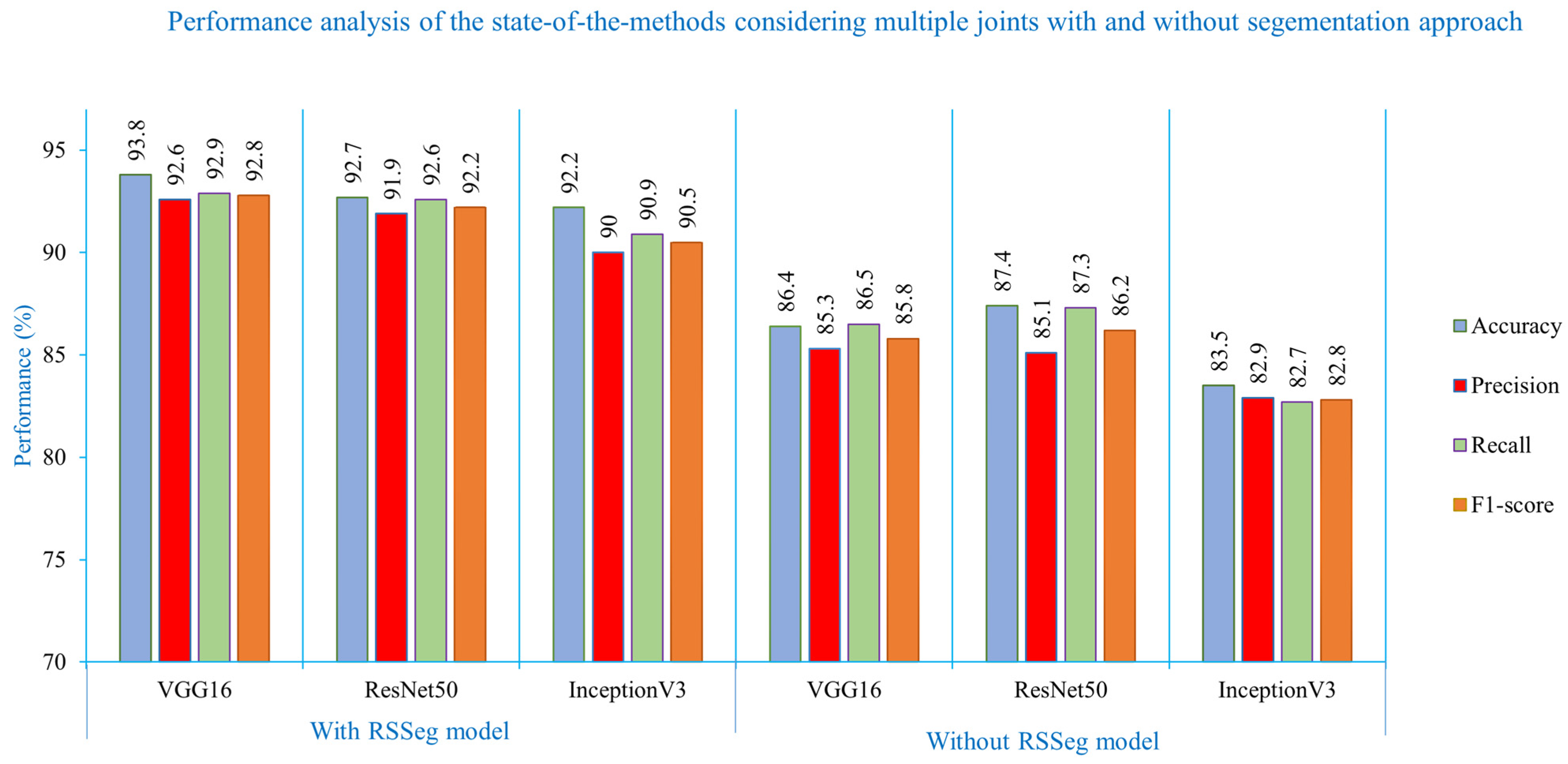

| Data Split | Evaluation Metrix | Models | With Segmentation | Without Segmentation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGG16 | ResNet50 | InceptionV3 | VGG16 | ResNet50 | InceptionV3 | |||

| 60:40 | Accuracy (%) | Wrist | 94.1 | 92.4 | 89.8 | 85.6 | 89.3 | 82.8 |

| Elbow | 92.1 | 93.2 | 92.4 | 85.6 | 87.3 | 84.3 | ||

| Shoulder | 93.7 | 91.2 | 91.8 | 84.2 | 84.4 | 83.1 | ||

| Pelvis | 88.9 | 90.4 | 88.9 | 85.5 | 83.3 | 79.7 | ||

| Overall | 92.2 | 91.8 | 90.7 | 85.2 | 86.1 | 82.5 | ||

| Precision (%) | Wrist | 93.1 | 92.9 | 89.2 | 85.1 | 87.6 | 83.2 | |

| Elbow | 92.1 | 92.4 | 89.5 | 86.2 | 88.2 | 86.3 | ||

| Shoulder | 92.1 | 88.8 | 90.4 | 83.6 | 81.4 | 79.4 | ||

| Pelvis | 86.9 | 87.9 | 86.7 | 80.6 | 81.2 | 78.6 | ||

| Overall | 91.1 | 90.5 | 89.0 | 83.9 | 84.6 | 81.9 | ||

| Recall (%) | Wrist | 92.6 | 94.5 | 89.8 | 84.9 | 88.5 | 83.2 | |

| Elbow | 92.6 | 93.2 | 91.1 | 86.8 | 89.8 | 82.6 | ||

| Shoulder | 89.6 | 90.1 | 90.7 | 83.6 | 86.5 | 81.4 | ||

| Pelvis | 88.8 | 88.3 | 86.9 | 83.4 | 82.1 | 80.7 | ||

| Overall | 90.9 | 91.5 | 89.6 | 84.7 | 86.7 | 82.0 | ||

| F1-score (%) | Wrist | 92.8 | 93.7 | 89.5 | 85.00 | 88.05 | 83.2 | |

| Elbow | 92.3 | 92.8 | 90.3 | 86.5 | 88.99 | 84.4 | ||

| Shoulder | 90.8 | 89.4 | 90.5 | 83.6 | 83.9 | 80.4 | ||

| Pelvis | 87.8 | 88.1 | 86.8 | 81.98 | 81.6 | 79.6 | ||

| Overall | 90.9 | 91.0 | 89.3 | 84.3 | 85.6 | 81.9 | ||

| 70:30 | Accuracy (%) | Wrist | 94.9 | 93.9 | 91.1 | 86.1 | 87.7 | 84.3 |

| Elbow | 93.7 | 90.9 | 91.8 | 85.4 | 86.3 | 84.2 | ||

| Shoulder | 92.1 | 91.7 | 91.5 | 86.4 | 85.3 | 82.6 | ||

| Pelvis | 89.9 | 89.8 | 88.5 | 84.5 | 84 | 78.6 | ||

| Overall | 92.7 | 91.6 | 90.7 | 85.6 | 85.8 | 82.4 | ||

| Precision (%) | Wrist | 93.9 | 92.4 | 88.7 | 86.4 | 86.8 | 83.1 | |

| Elbow | 91.7 | 91.8 | 89.3 | 84.7 | 86.5 | 85.3 | ||

| Shoulder | 91.8 | 89.2 | 87.9 | 85.1 | 80.4 | 79.3 | ||

| Pelvis | 87.5 | 86.9 | 86.4 | 80.2 | 79.8 | 78.7 | ||

| Overall | 91.2 | 90.1 | 88.1 | 84.1 | 83.4 | 81.6 | ||

| Recall (%) | Wrist | 94.4 | 95.1 | 89.8 | 85.6 | 87.7 | 83.2 | |

| Elbow | 90.2 | 91.5 | 88.5 | 84.0 | 84.5 | 80.5 | ||

| Shoulder | 91.7 | 91.8 | 87.7 | 85.7 | 86.4 | 82.2 | ||

| Pelvis | 89.7 | 88.1 | 86.2 | 83.7 | 82.6 | 79.2 | ||

| Overall | 91.5 | 91.63 | 88.1 | 84.8 | 85.3 | 81.3 | ||

| F1-score (%) | Wrist | 94.1 | 93.7 | 89.2 | 86.0 | 87.2 | 83.1 | |

| Elbow | 90.9 | 91.6 | 88.9 | 84.3 | 85.5 | 82.8 | ||

| Shoulder | 91.7 | 90.5 | 87.8 | 85.4 | 83.3 | 80.7 | ||

| Pelvis | 88.6 | 87.5 | 86.3 | 81.9 | 81.2 | 78.9 | ||

| Overall | 91.4 | 90.8 | 88.1 | 84.4 | 84.3 | 81.4 | ||

| 80:20 | Accuracy (%) | Wrist | 95.9 | 94.2 | 92.5 | 87.8 | 89.5 | 84.5 |

| Elbow | 94.6 | 93.1 | 93.7 | 85.8 | 88.5 | 85.6 | ||

| Shoulder | 93.9 | 92.5 | 91.9 | 86.5 | 86.9 | 83.8 | ||

| Pelvis | 90.8 | 91.0 | 90.6 | 85.5 | 84.6 | 80.1 | ||

| Overall | 93.8 | 92.7 | 92.2 | 86.4 | 87.4 | 83.5 | ||

| Precision (%) | Wrist | 94.8 | 94.2 | 90.1 | 86.9 | 87.9 | 84.8 | |

| Elbow | 93.6 | 93.8 | 90.4 | 86.1 | 88.2 | 86.7 | ||

| Shoulder | 92.9 | 91.2 | 90.8 | 85.8 | 82.5 | 80.7 | ||

| Pelvis | 89.2 | 88.6 | 88.7 | 82.4 | 81.7 | 79.4 | ||

| Overall | 92.6 | 92.0 | 90.0 | 85.3 | 85.1 | 82.9 | ||

| Recall (%) | Wrist | 95.0 | 95.1 | 91.3 | 87.4 | 89.0 | 83.5 | |

| Elbow | 94.2 | 93.5 | 92.8 | 88.8 | 90.1 | 84.1 | ||

| Shoulder | 91.7 | 91.8 | 90.7 | 85.7 | 86.4 | 82.2 | ||

| Pelvis | 90.7 | 89.8 | 88.9 | 83.9 | 83.7 | 81.1 | ||

| Overall | 92.9 | 92.6 | 90.9 | 86.5 | 87.3 | 82.7 | ||

| F1-score (%) | Wrist | 94.9 | 94.6 | 90.7 | 87.1 | 88.4 | 84.1 | |

| Elbow | 93.9 | 93.6 | 91.6 | 87.4 | 89.1 | 85.4 | ||

| Shoulder | 92.3 | 91.5 | 90.7 | 85.7 | 84.4 | 81.4 | ||

| Pelvis | 89.9 | 89.2 | 88.8 | 83.1 | 82.7 | 80.2 | ||

| Overall | 92.8 | 92.2 | 90.5 | 85.9 | 86.2 | 82.8 | ||

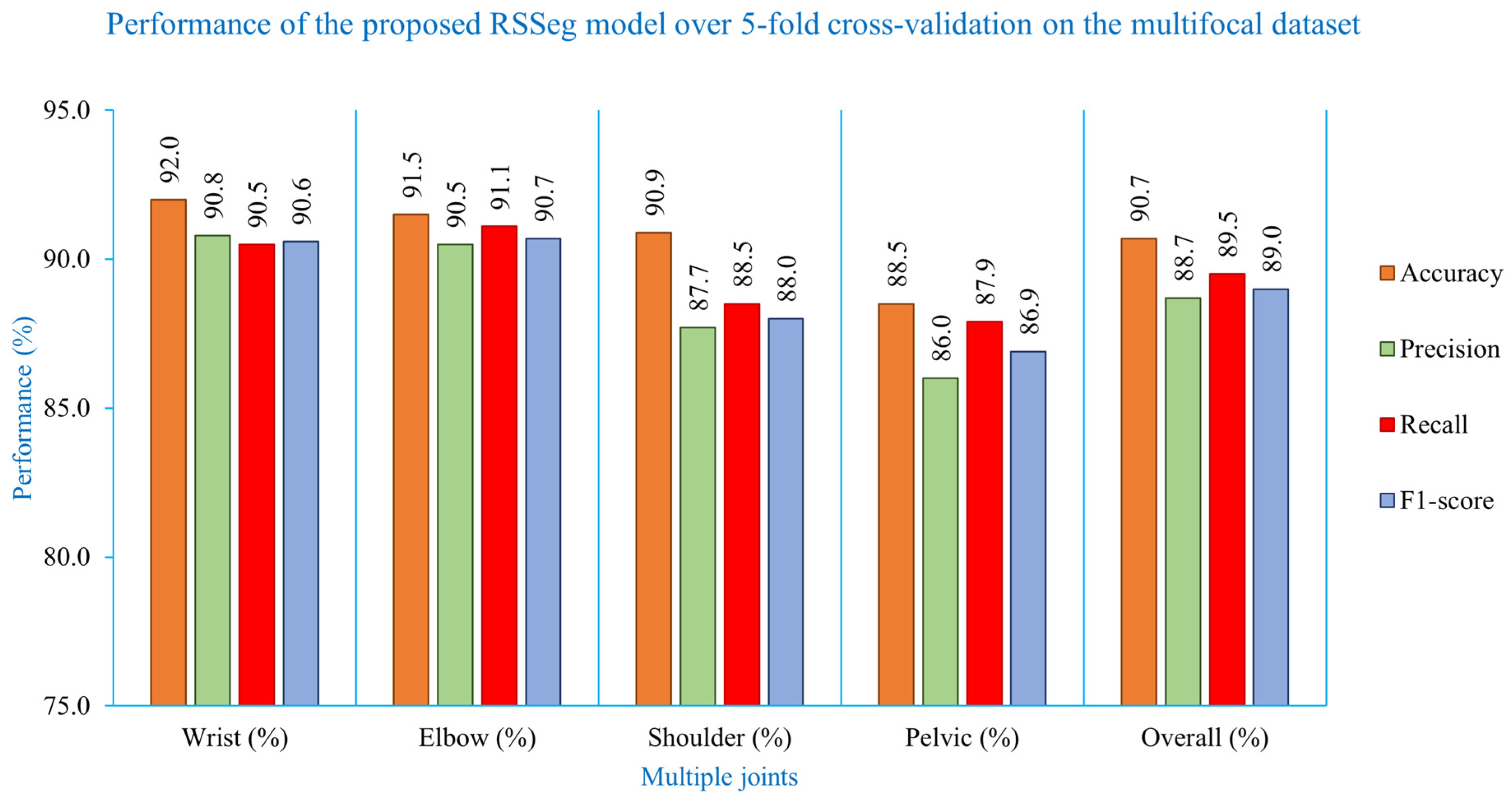

| Metric | Wrist (%) | Elbow (%) | Shoulder (%) | Pelvis (%) | Overall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 92.0 ± 3.30 | 91.5 ± 3.22 | 90.9 ± 3.10 | 88.5 ± 2.31 | 90.7 ± 2.98 |

| Precision | 90.8 ± 3.71 | 90.5 ± 3.29 | 87.7 ± 4.03 | 86.0 ± 3.68 | 88.7 ± 3.68 |

| Recall | 90.5 ± 4.50 | 91.1 ± 3.13 | 88.5 ± 3.61 | 87.9 ± 3.24 | 89.5 ± 3.62 |

| F1-score | 90.6 ± 3.98 | 90.7 ± 3.15 | 88.0 ± 3.73 | 86.9 ± 3.44 | 89.0 ± 3.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manchegowda, P.; Nageshmurthy, M.; Raju, S.; Rudrappa, D. A Multifocal RSSeg Approach for Skeletal Age Estimation in an Indian Medicolegal Perspective. Algorithms 2025, 18, 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18120765

Manchegowda P, Nageshmurthy M, Raju S, Rudrappa D. A Multifocal RSSeg Approach for Skeletal Age Estimation in an Indian Medicolegal Perspective. Algorithms. 2025; 18(12):765. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18120765

Chicago/Turabian StyleManchegowda, Priyanka, Manohar Nageshmurthy, Suresha Raju, and Dayananda Rudrappa. 2025. "A Multifocal RSSeg Approach for Skeletal Age Estimation in an Indian Medicolegal Perspective" Algorithms 18, no. 12: 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18120765

APA StyleManchegowda, P., Nageshmurthy, M., Raju, S., & Rudrappa, D. (2025). A Multifocal RSSeg Approach for Skeletal Age Estimation in an Indian Medicolegal Perspective. Algorithms, 18(12), 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18120765