Ensemble Modeling of Multiple Physical Indicators to Dynamically Phenotype Autism Spectrum Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Digital Phenotyping of Autism

2.2. Data Fusion for ASD Classification

3. Materials and Methods

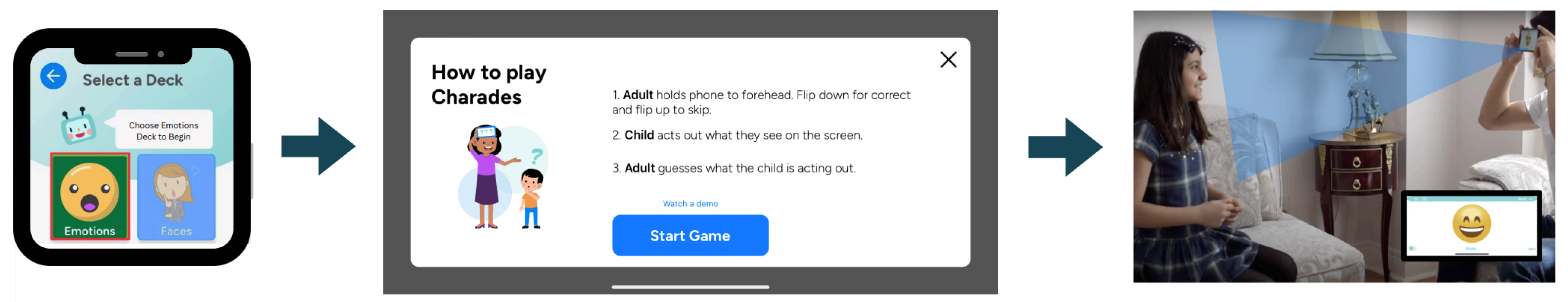

3.1. Dataset

3.1.1. Data Collection and Type

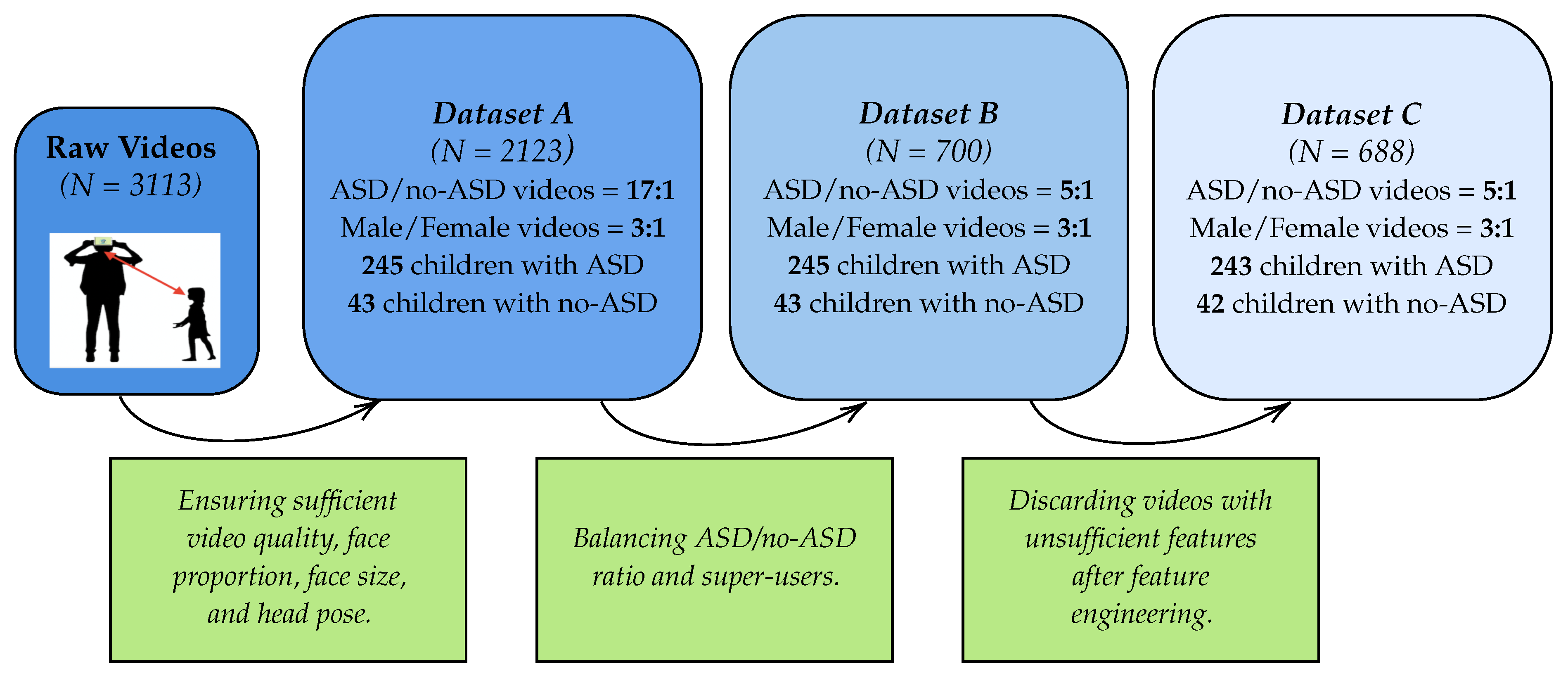

3.1.2. Filtering Pipeline

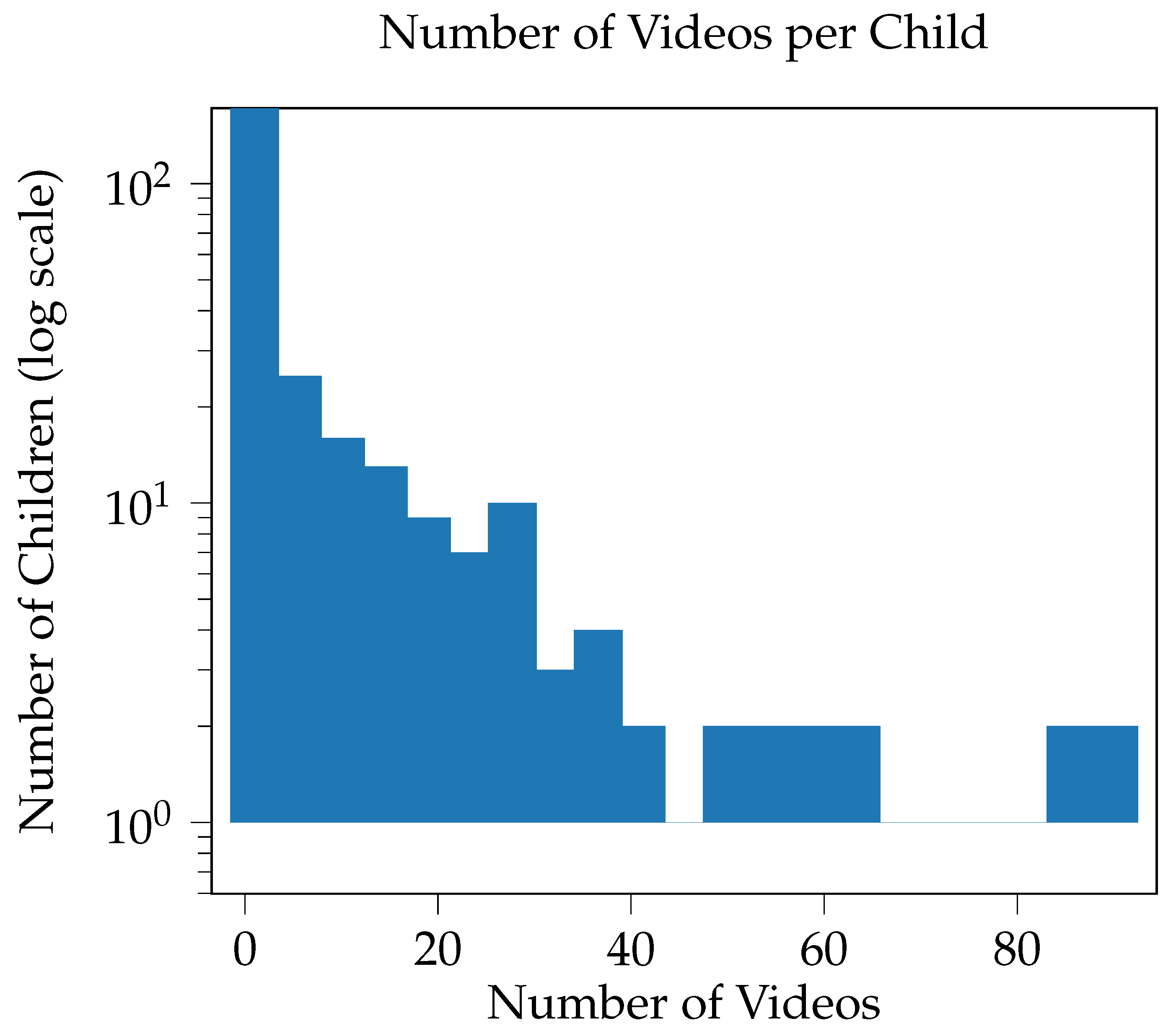

3.1.3. Bias and Imbalances

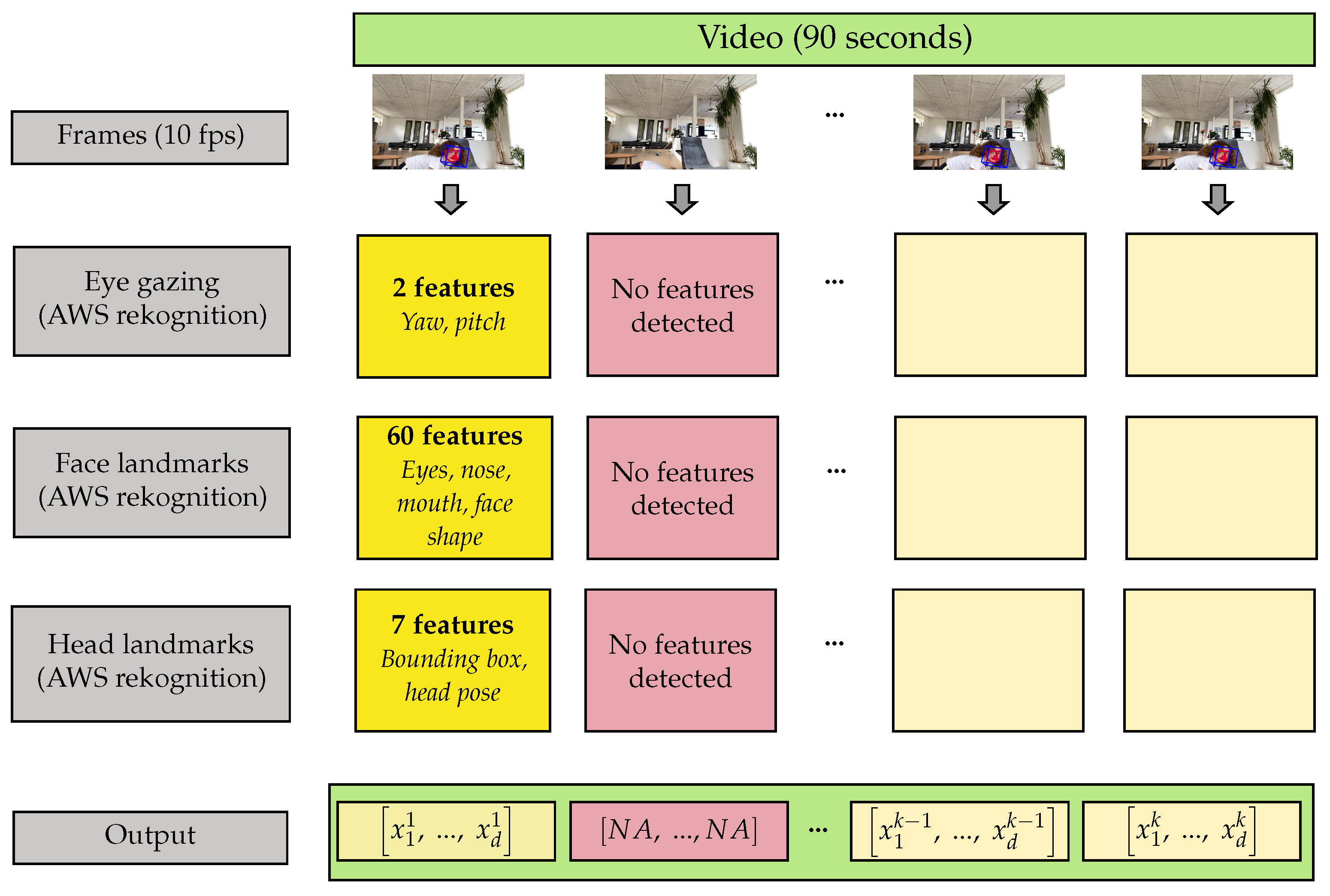

3.2. Feature Extraction

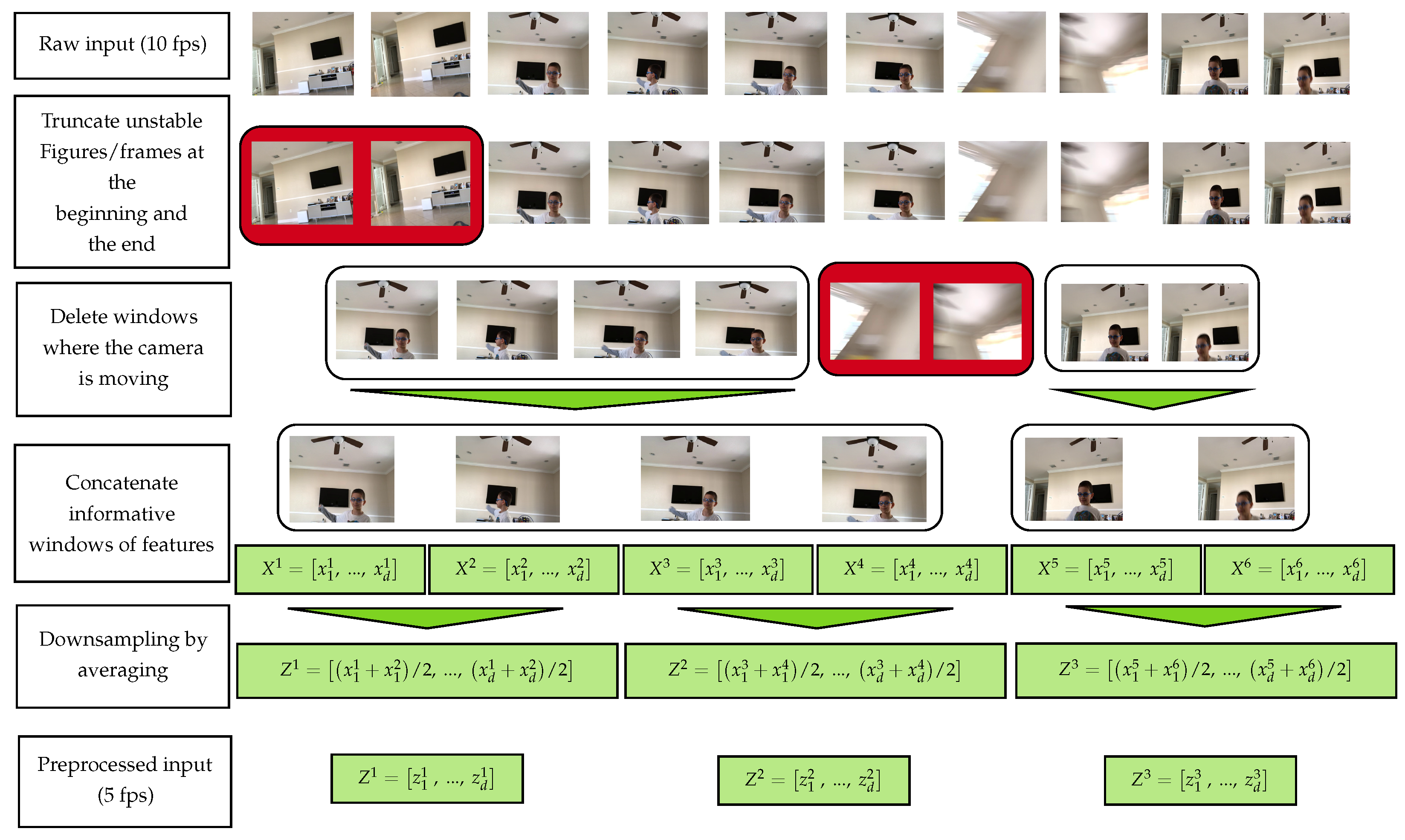

3.3. Data Preprocessing

3.4. Model Training

3.4.1. Data Splitting and Task Definition

3.4.2. Unimodal Deep Time-Series Models

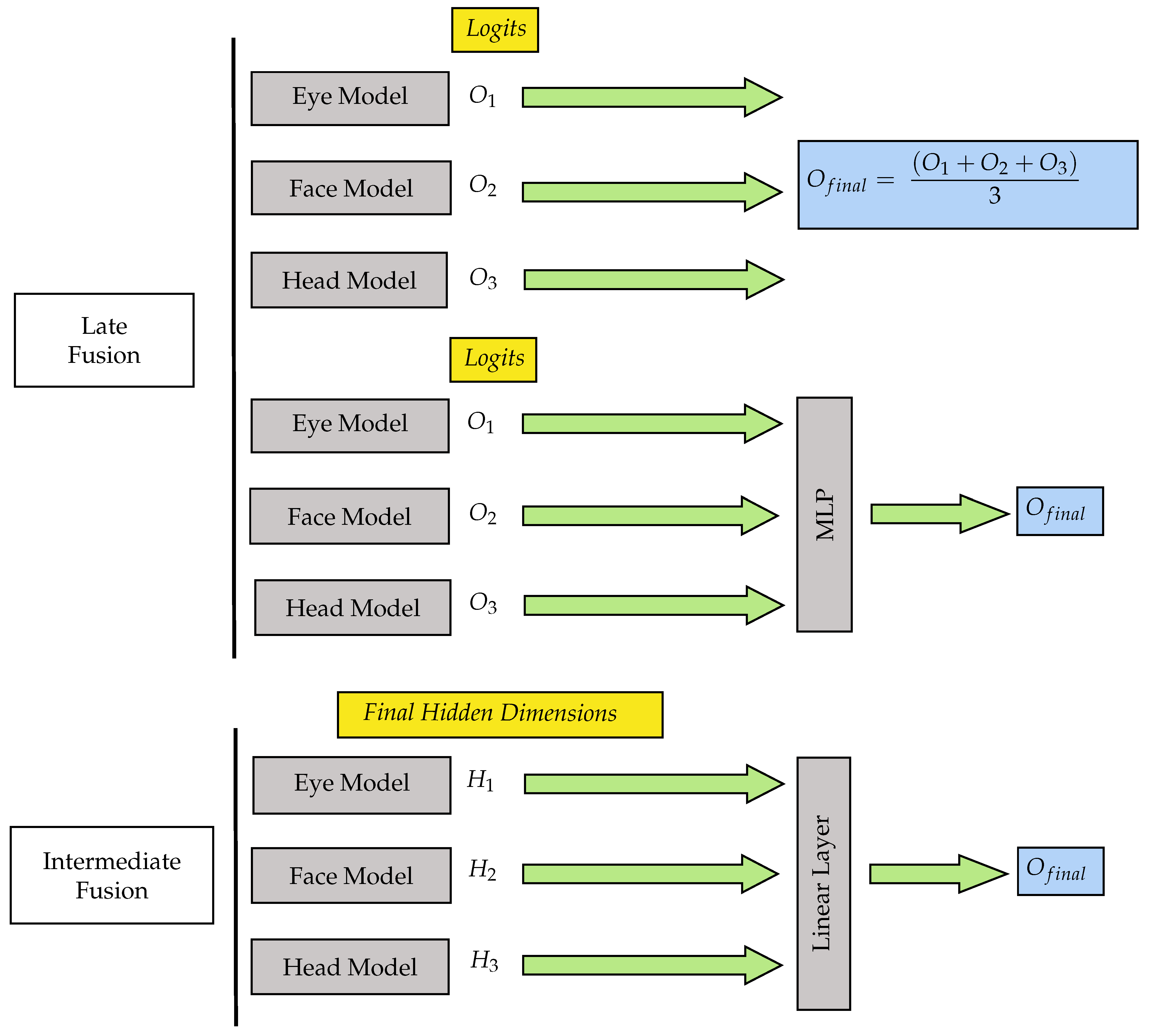

3.4.3. Fusion and Ensemble Techniques

3.4.4. Hyperparameter Optimization

4. Results

4.1. Effects of Feature Engineering

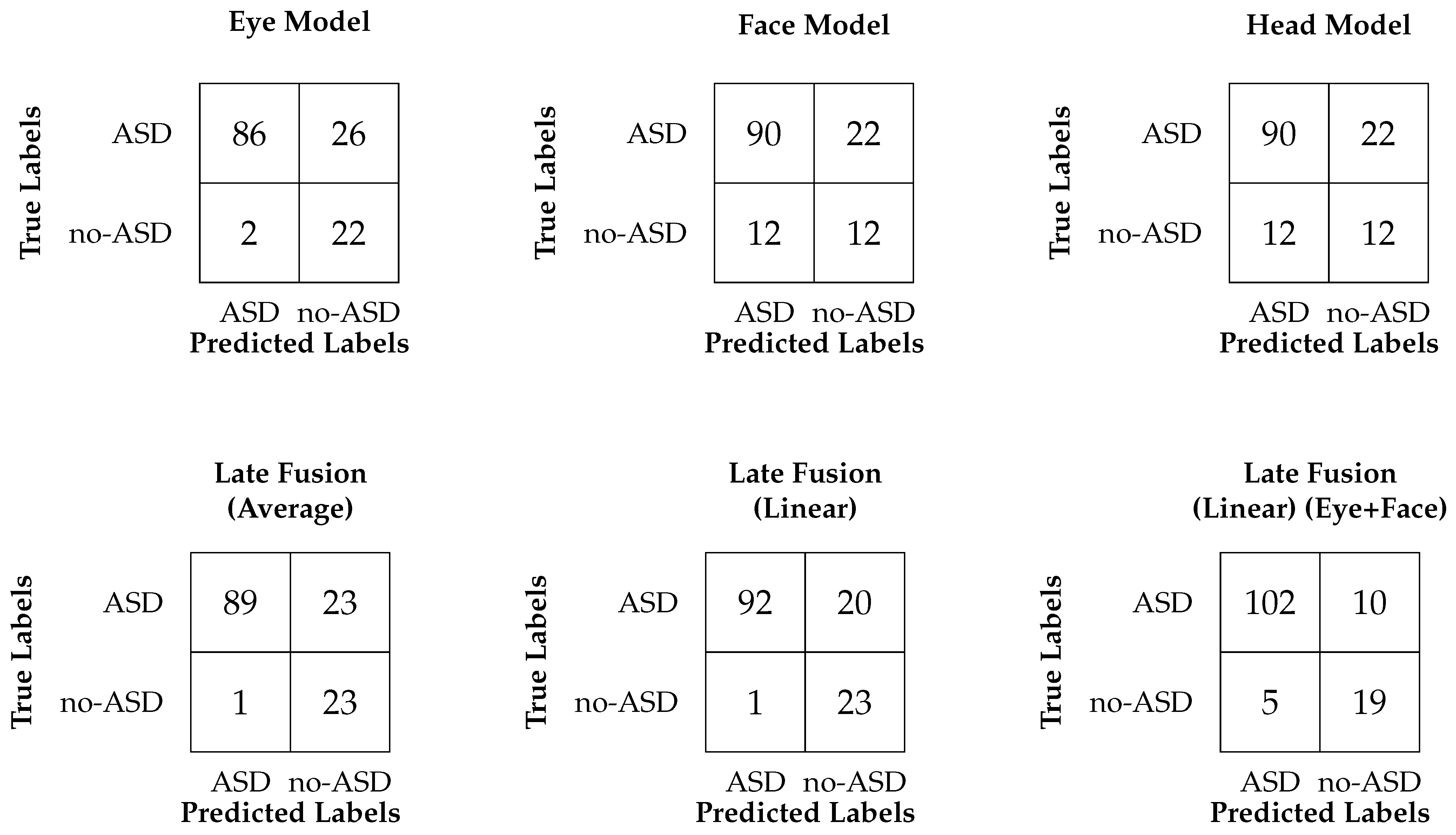

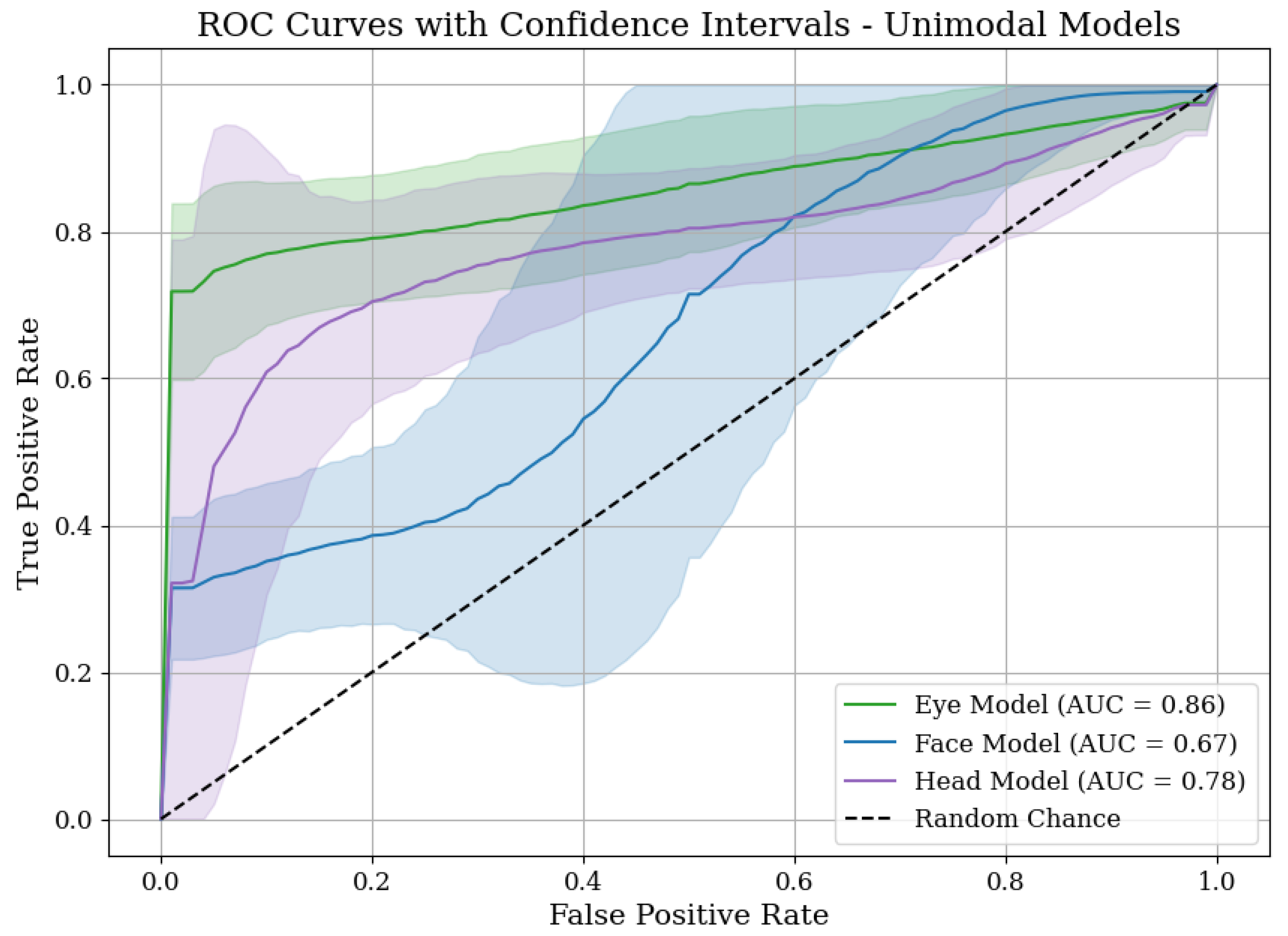

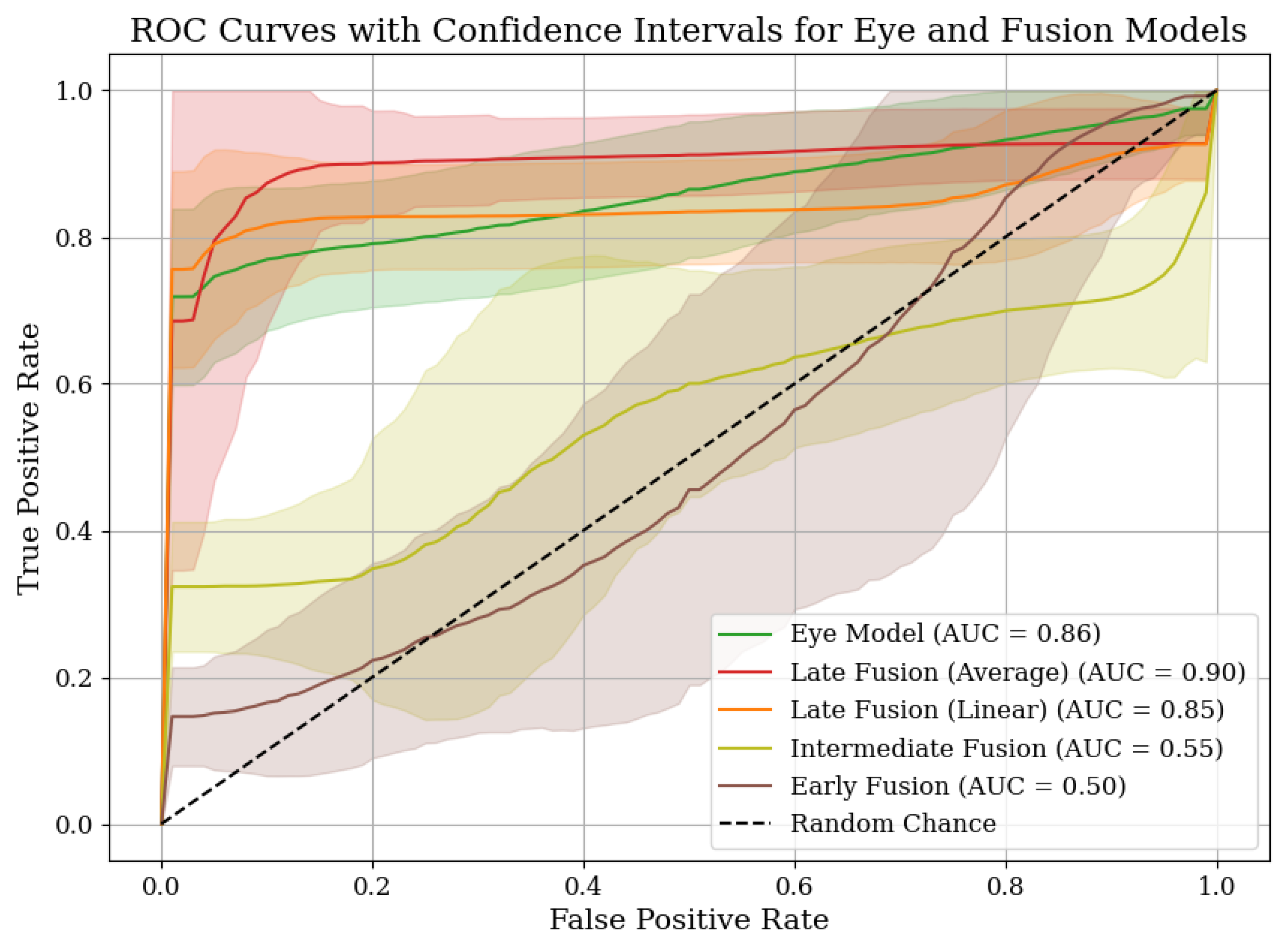

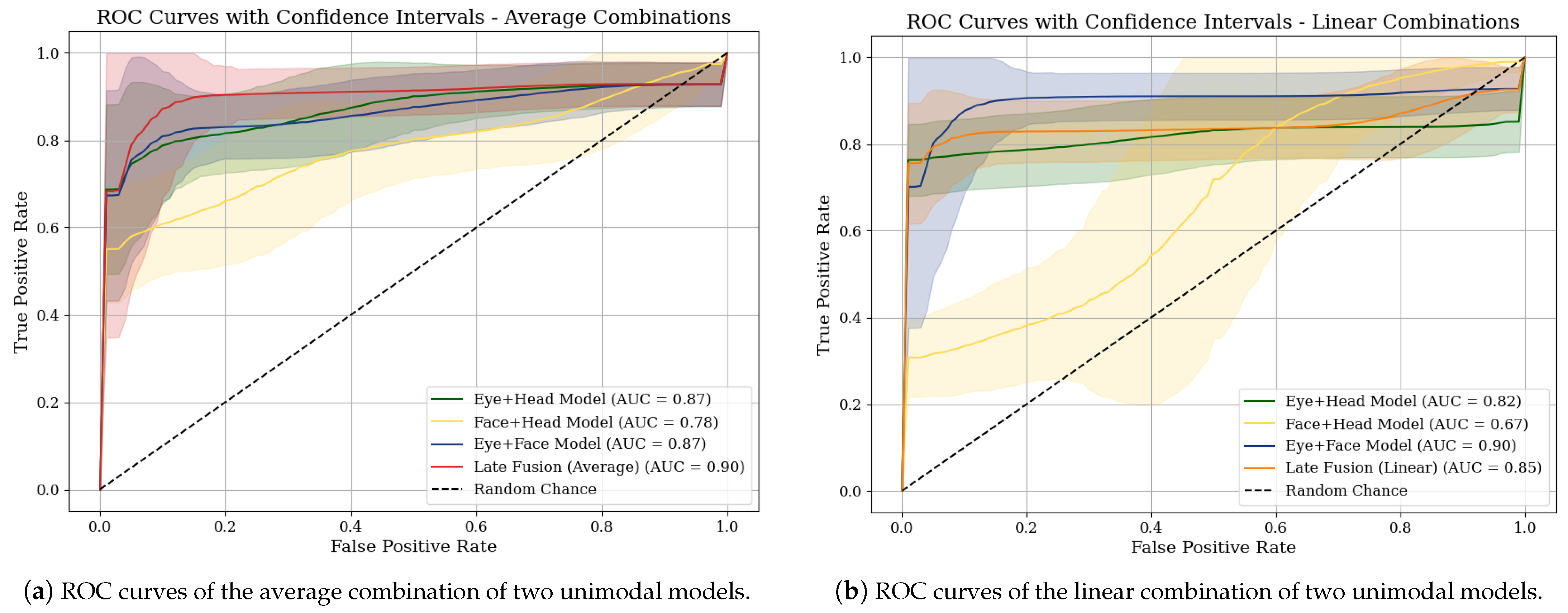

4.2. Performance Comparison of Our Models

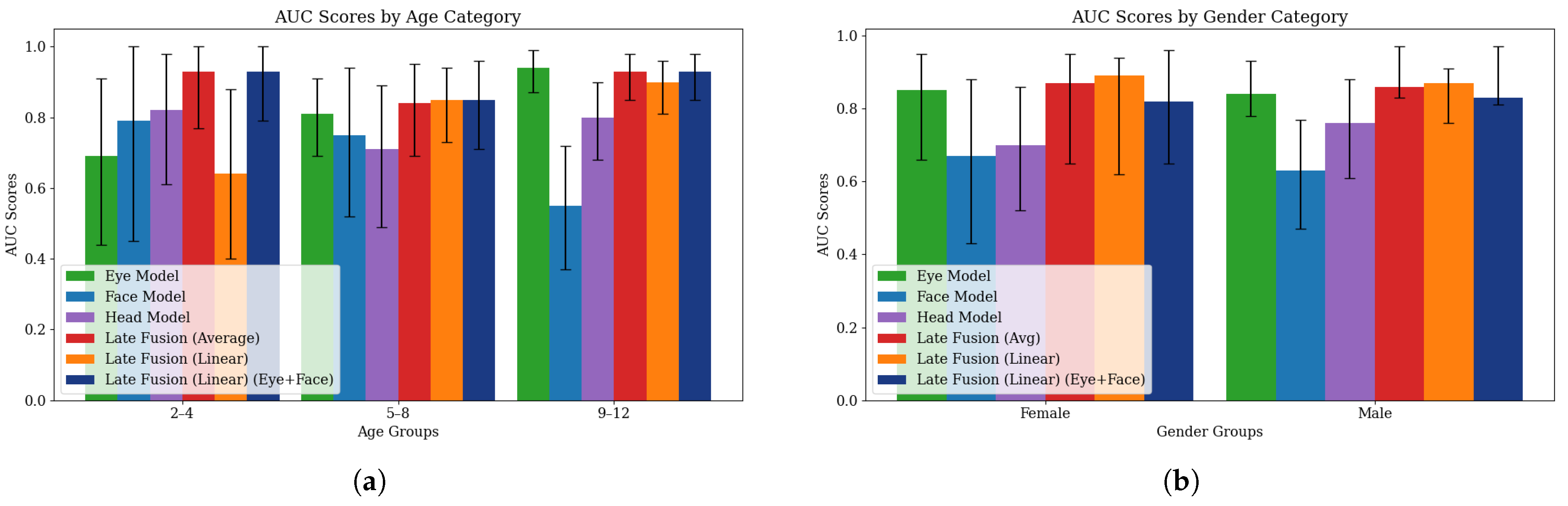

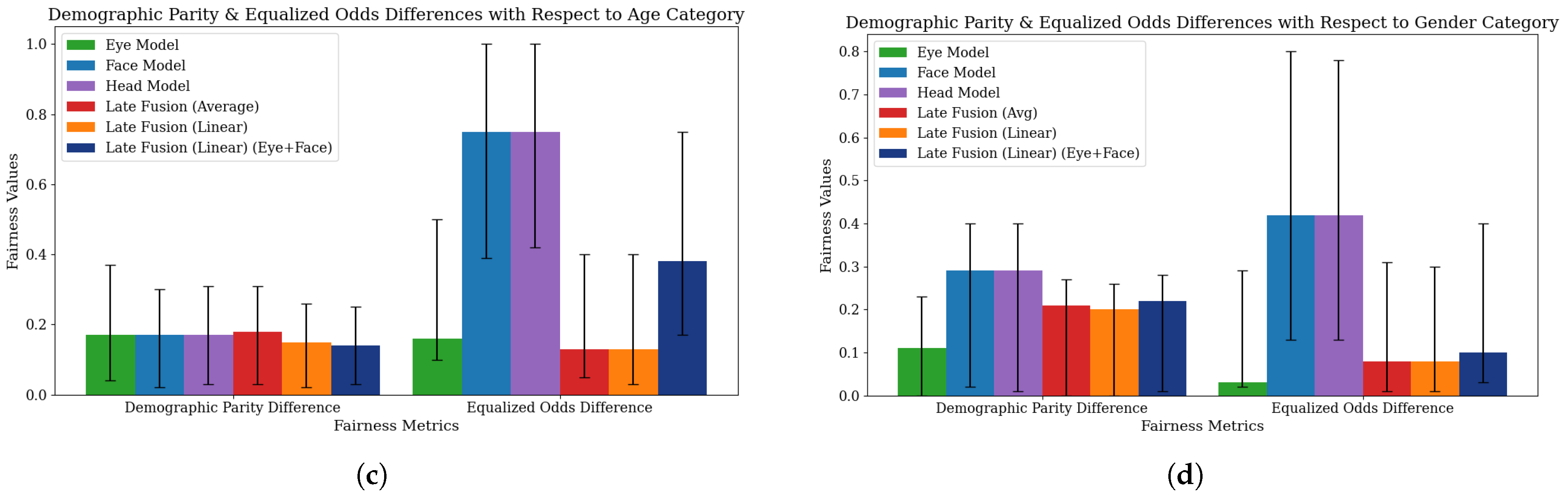

4.3. Fairness Evaluation

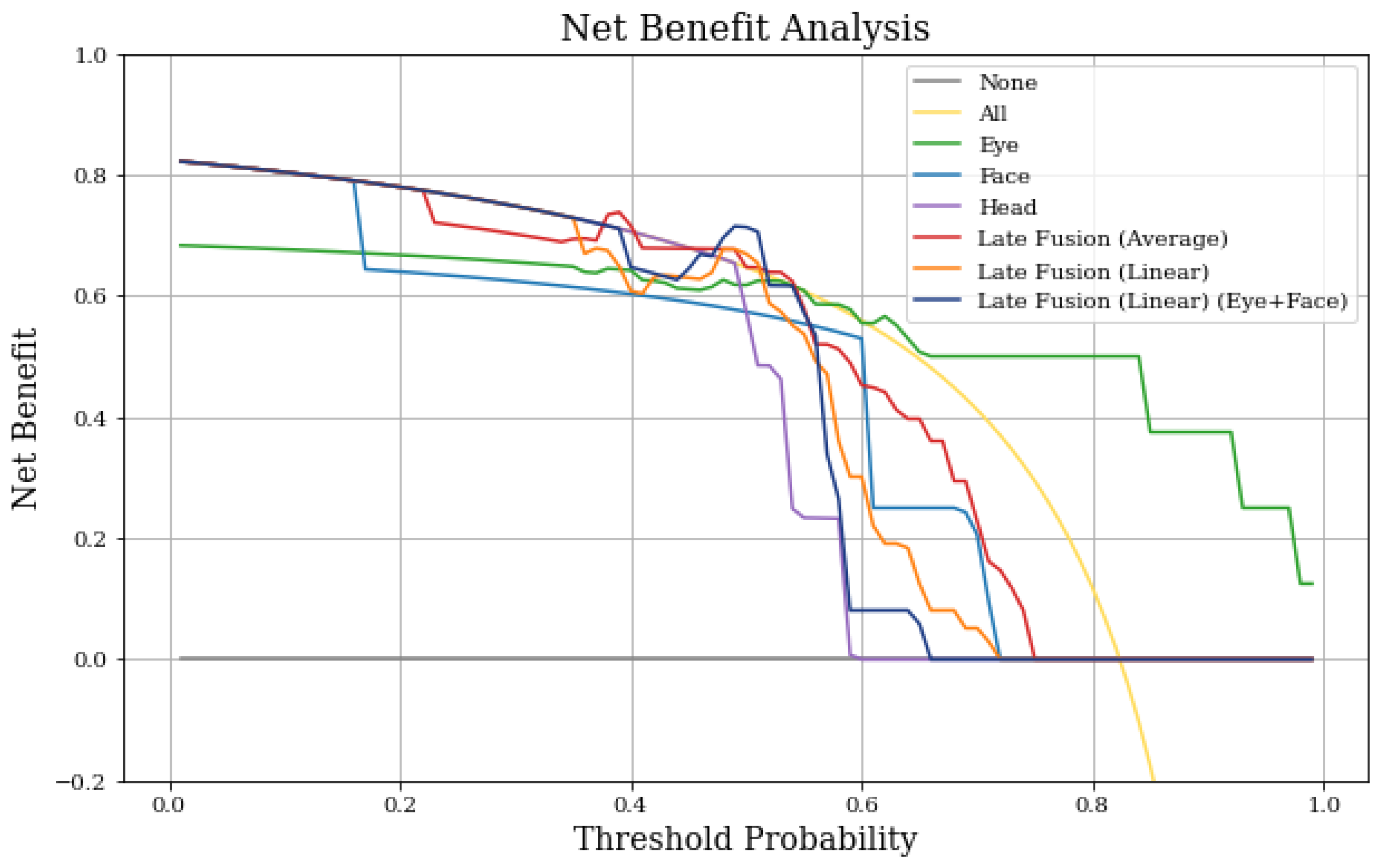

4.4. Net Benefit Analysis

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| MA | Macro-averaged |

| WA | Weighted-averaged |

Appendix A

| Filtering Criteria | Variables | Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

| Quality | Sharpness, brightness | Sharpness (0–100) > 4; Brightness (0–100) > 20 |

| Face Detection | No face proportion, Multi-face proportion, Face size | No face detection (0–1) < 0.6; Multi-face detection (0–1) < 0.3; Face size (0–100) > 0.01 |

| Eye Visibility | Head pose (pitch, roll, yaw), Eyes’ confidence | Pitch (–180) < 45; Roll (–180) < 45; Yaw (–180) < 45; Eyes’ confidence (0–100) > 75 |

| Hyperparameter | Range Searched |

|---|---|

| Model | LSTM, GRU, CNN+LSTM, CNN+GRU |

| Hidden Size (of LSTM/GRU) | {16, 32, 64} |

| Batch Size | {32, 48, 64, 100} |

| Number of Layers | [4, 8] |

| Dropout Probability | [0.1, 0.3] |

| Learning Rate | [, ] |

| Weight Decay | [, ] |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Loss Function | Cross-entropy, focal loss |

| Hyperparameter | Range Searched |

|---|---|

| Batch Size | {16, 32, 64} |

| Learning Rate | [, ] |

| First Hidden Size | {128, 192, 256} |

| Second Hidden Size | {32, 64, 128} |

| Third Hidden Size | {32, 64} |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Loss Function | Cross-entropy |

| Hyperparameter | Eye Gazing | Head Pose | Facial Landmarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | LSTM | LSTM | LSTM |

| Hidden Size | 64 | 32 | 48 |

| Batch Size | 64 | 48 | 48 |

| Number of Layers | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Dropout Probability | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.18 |

| Learning Rate | 0.03 | 0.0003 | 0.05 |

| Weight Decay | |||

| Optimizer | Adam | Adam | Adam |

| Loss Function | Cross-Entropy | Cross-Entropy | Cross-Entropy |

| Model | AUC Score | F1 Score (MA) |

|---|---|---|

| Eye (No Upsampling) | 0.86 | 0.73 |

| Eye (Upsampling) | 0.76 | 0.62 |

| Head (No Upsampling) | 0.78 | 0.63 |

| Head (Upsampling) | 0.60 | 0.56 |

| Face (No Upsampling) | 0.67 | 0.63 |

| Face (Upsampling) | 0.76 | 0.61 |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Batch Size | 16 |

| Learning Rate | 0.07 |

| First Hidden Size | 256 |

| Second Hidden Size | 32 |

| Third Hidden Size | 64 |

| Number of Epochs | 15 |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Batch Size | 32 |

| Learning Rate | |

| Number of Epochs | 11 |

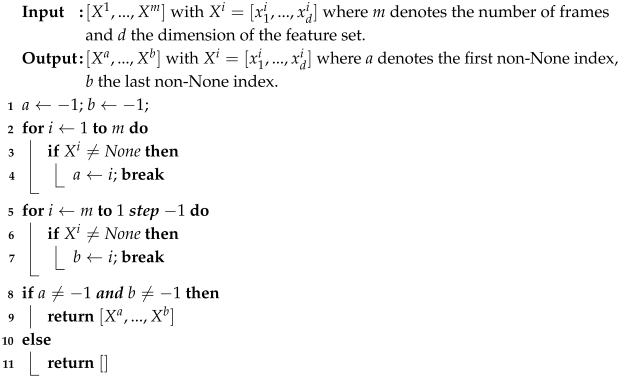

| Algorithm A1: Truncate Window |

|

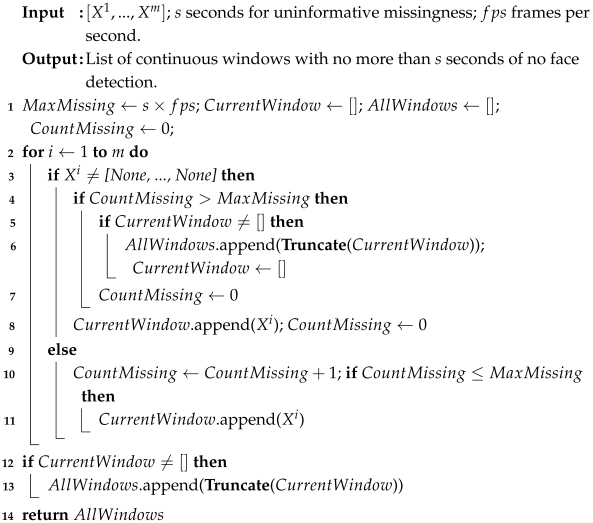

| Algorithm A2: Create Windows |

|

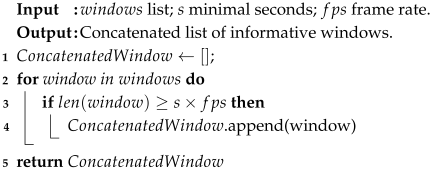

| Algorithm A3: Concatenate Windows |

|

References

- Maenner, M.J.; Warren, Z.; Williams, A.R.; Amoakohene, E.; Bakian, A.V.; Bilder, D.A.; Durkin, M.S.; Fitzgerald, R.T.; Furnier, S.M.; Hughes, M.M.; et al. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2023, 72, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.P.; Myers, S.M.; The Council on Children with Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2007, 120, 1183–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, J.; Frye, R.E.; Walker, S.J. The lifetime social cost of autism: 1990–2029. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2020, 72, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, G.; Zanolli, K. Early intervention and brain plasticity in autism. In Autism: Neural Basis and Treatment Possibilities: Novartis Foundation Symposium 251; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; Volume 251, pp. 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Risi, S.; DiLavore, P.S.; Shulman, C.; Thurm, A.; Pickles, A. Autism from 2 to 9 years of age. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Lin, J.; Feng, C.; Iqbal, J. Biomarkers in autism spectrum disorders: Current progress. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 502, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Lipkin, E.; Foster, J.; Peacock, G. Whittling down the wait time: Exploring models to minimize the delay from initial concern to diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Pediatr. Clin. 2016, 63, 851–859. [Google Scholar]

- First, M.B. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, and clinical utility. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2013, 201, 727–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazefsky, C.A.; Oswald, D.P. The discriminative ability and diagnostic utility of the ADOS-G, ADI-R, and GARS for children in a clinical setting. Autism 2006, 10, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.J.; Long, K.A.; Tommet, D.C.; Jones, R.N. Examining the role of race, ethnicity, and gender on social and behavioral ratings within the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 2770–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, M.R.; Childs, A.W.; Richards, M.; Robins, D.L. Race influences parent report of concerns about symptoms of autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2019, 23, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalb, L.G.; Singh, V.; Hong, J.S.; Holingue, C.; Ludwig, N.N.; Pfeiffer, D.; Reetzke, R.; Gross, A.L.; Landa, R. Analysis of race and sex bias in the autism diagnostic observation schedule (ADOS-2). JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e229498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantarian, H.; Washington, P.; Schwartz, J.; Daniels, J.; Haber, N.; Wall, D. A gamified mobile system for crowdsourcing video for autism research. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI), New York, NY, USA, 4–7 June 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 350–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantarian, H.; Jedoui, K.; Washington, P.; Tariq, Q.; Dunlap, K.; Schwartz, J.; Wall, D.P. Labeling images with facial emotion and the potential for pediatric healthcare. Artif. Intell. Med. 2019, 98, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penev, Y.; Dunlap, K.; Husic, A.; Hou, C.; Washington, P.; Leblanc, E.; Kline, A.; Kent, J.; Ng-Thow-Hing, A.; Liu, B.; et al. A mobile game platform for improving social communication in children with autism: A feasibility study. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2021, 12, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Tang, H.; Xing, J.; Hu, X.; Lu, J.; Qu, X. Identifying autism with head movement features by implementing machine learning algorithms. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 3038–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakkapragada, A.; Kline, A.; Mutlu, O.C.; Paskov, K.; Chrisman, B.; Stockham, N.; Washington, P.; Wall, D.P. The classification of abnormal hand movement to aid in autism detection: Machine learning study. JMIR Biomed. Eng. 2022, 7, e33771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapiro, G.; Hashemi, J.; Dawson, G. Computer vision and behavioral phenotyping: An autism case study. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 9, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, G.; Campbell, K.; Hashemi, J.; Lippmann, S.J.; Smith, V.; Carpenter, K.; Egger, H.; Espinosa, S.; Vermeer, S.; Baker, J.; et al. Atypical postural control can be detected via computer vision analysis in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Di Martino, J.M.; Aiello, R.; Baker, J.; Carpenter, K.; Compton, S.; Davis, N.; Eichner, B.; Espinosa, S.; Flowers, J.; et al. Computational methods to measure patterns of gaze in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülü, M.; Büyükbayraktar, F.; Köroğlu, Ç.; Gündoğdu, R.; Akan, A. Machine learning-based prediction of autism spectrum disorder from eye tracking data: A systematic review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 164, 113938. [Google Scholar]

- Liaqat, S.; Wu, C.; Duggirala, P.R.; Cheung, S.c.S.; Chuah, C.N.; Ozonoff, S.; Young, G. Predicting ASD diagnosis in children with synthetic and image-based eye gaze data. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2021, 94, 116198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, M.; Washington, P.; Chrisman, B.; Kline, A.; Leblanc, E.; Paskov, K.; Stockham, N.; Jung, J.Y.; Sun, M.W.; Wall, D.P. Identification of Social Engagement Indicators Associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder Using a Game-Based Mobile App: Comparative Study of Gaze Fixation and Visual Scanning Methods. J. Med Internet Res. 2022, 24, e31830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Hashiya, K. Advanced Variations in Eye-Tracking Methodologies for Autism Diagnostics. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 1234–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, K.B.; Hammal, Z.; Ren, G.; Cohn, J.F.; Cassell, J.; Ogihara, M.; Britton, J.C.; Gutierrez, A.; Messinger, D.S. Objective measurement of head movement differences in children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism 2018, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Pathak, A.; Ganai, U.J.; Bhushan, B.; Subramanian, V.K. Video Based Computational Coding of Movement Anomalies in ASD Children. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024; pp. 400–409. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnappababu, P.R.; Di Martino, M.; Chang, Z.; Perochon, S.P.; Carpenter, K.L.; Compton, S.; Espinosa, S.; Dawson, G.; Sapiro, G. Exploring complexity of facial dynamics in autism spectrum disorder. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2021, 14, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Francis, S.M.; Srishyla, D.; Conelea, C.; Zhao, Q.; Jacob, S. Classifying individuals with ASD through facial emotion recognition and eye-tracking. In Proceedings of the 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Berlin, Germany, 23–27 July 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 6063–6068. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A.; Mutlu, O.C.; Kline, A.; Surabhi, S.; Washington, P.; Wall, D.P. Training and profiling a pediatric facial expression classifier for children on mobile devices: Machine learning study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e39917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Li, J.; Ouyang, G. Early diagnosis of asd based on facial expression recognition and head pose estimation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Prague, Czech Republic, 9–12 October 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1248–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Simeoli, R.; Milano, N.; Rega, A.; Marocco, D. Using technology to identify children with autism through motor abnormalities. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 635696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, C.; Narzisi, A.; Milone, A.; Masi, G.; Pirrelli, V. Reading Behaviors through Patterns of Finger-Tracking in Italian Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vabalas, A.; Gowen, E.; Poliakoff, E.; Casson, A.J. Applying machine learning to kinematic and eye movement features of a movement imitation task to predict autism diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.A.; Washington, P.; Kline, A.; Husic, A.; Hou, C.; He, C.; Dunlap, K.; Wall, D.P. Classifying autism from crowdsourced semistructured speech recordings: Machine learning model comparison study. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2022, 5, e35406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, I.S.; Koehler, J.C.; Nelson, A.M.; Koutsouleris, N.; Falter-Wagner, C. Automated extraction of speech and turn-taking parameters in autism allows for diagnostic classification using a multivariable prediction model. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1257569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantarian, H.; Jedoui, K.; Dunlap, K.; Schwartz, J.; Washington, P.; Husic, A.; Tariq, Q.; Ning, M.; Kline, A.; Wall, D.P.; et al. The performance of emotion classifiers for children with parent-reported autism: Quantitative feasibility study. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e13174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, P.; Kalantarian, H.; Kent, J.; Husic, A.; Kline, A.; Leblanc, E.; Hou, C.; Mutlu, O.C.; Dunlap, K.; Penev, Y.; et al. Improved digital therapy for developmental pediatrics using domain-specific artificial intelligence: Machine learning study. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2022, 5, e26760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perochon, S.; Di Martino, J.M.; Carpenter, K.L.; Compton, S.; Davis, N.; Eichner, B.; Espinosa, S.; Franz, L.; Krishnappa Babu, P.R.; Sapiro, G.; et al. Early detection of autism using digital behavioral phenotyping. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2489–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnappa Babu, P.R.; Di Martino, J.M.; Aiello, R.; Eichner, B.; Espinosa, S.; Green, J.; Howard, J.; Perochon, S.; Spanos, M.; Vermeer, S.; et al. Validation of a Mobile App for Remote Autism Screening in Toddlers. NEJM AI 2024, 1, AIcs2400510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Jiang, G.; Ouyang, G.; Li, X. A multimodal approach for identifying autism spectrum disorders in children. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2022, 30, 2003–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhera, T. Multimodal Kernel-based discriminant correlation analysis data-fusion approach: An automated autism spectrum disorder diagnostic system. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2024, 47, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, P.; Park, N.; Srivastava, P.; Voss, C.; Kline, A.; Varma, M.; Tariq, Q.; Kalantarian, H.; Schwartz, J.; Patnaik, R.; et al. Data-driven diagnostics and the potential of mobile artificial intelligence for digital therapeutic phenotyping in computational psychiatry. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2020, 5, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, P.; Wall, D.P. A review of and roadmap for data science and machine learning for the neuropsychiatric phenotype of autism. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 2023, 6, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantarian, H.; Washington, P.; Schwartz, J.; Daniels, J.; Haber, N.; Wall, D.P. Guess What? Towards Understanding Autism from Structured Video Using Facial Affect. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2019, 3, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombonne, E.; Coppola, L.; Mastel, S.; O’Roak, B.J. Validation of autism diagnosis and clinical data in the SPARK cohort. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 3383–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, S.S. Vineland adaptive behavior scales. In Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 2618–2621. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino, J.N. Social responsiveness scale. In Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 2919–2929. [Google Scholar]

- Duda, M.; Daniels, J.; Wall, D.P. Clinical evaluation of a novel and mobile autism risk assessment. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 1953–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M.; Bailey, A.; Lord, C. The Social Communication Questionnaire; Western Psychological Services: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, T.W.; Dimitropoulos, A.; Abbeduto, L.; Armstrong-Brine, M.; Kralovic, S.; Shih, A.; Hardan, A.Y.; Youngstrom, E.A.; Uljarević, M.; Team, V.B.; et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Autism Symptom Dimensions Questionnaire. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2025, 67, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazon Rekognition Developer Guide. 2023. Available online: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/rekognition/latest/APIReference/Welcome.html (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Hou, C.; Kalantarian, H.; Washington, P.; Dunlap, K.; Wall, D.P. Leveraging video data from a digital smartphone autism therapy to train an emotion detection classifier. medRxiv 2021, 2021-07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantarian, H.; Jedoui, K.; Washington, P.; Wall, D.P. A mobile game for automatic emotion-labeling of images. IEEE Trans. Games 2018, 12, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Google. ML Kit: Machine Learning for Mobile Developers. Available online: https://developers.google.com/ml-kit (accessed on 11 November 2025).

| Demographic | Train | Test | Val | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD | No-ASD | ASD | No-ASD | ASD | No-ASD | |

| Age | ||||||

| 2–4 | 19 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 1 |

| 5–8 | 67 | 10 | 17 | 5 | 19 | 5 |

| 9–12 | 61 | 7 | 24 | 3 | 21 | 2 |

| 13–17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 114 | 11 | 35 | 5 | 39 | 5 |

| Female | 34 | 12 | 11 | 6 | 10 | 3 |

| Location | ||||||

| United States | 65 | 2 | 25 | 1 | 24 | 0 |

| Outside US | 16 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| Unknown | 67 | 21 | 21 | 5 | 21 | 6 |

| Demographic | Train | Test | Val | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD | No-ASD | ASD | No-ASD | ASD | No-ASD | |

| Age | ||||||

| 2–4 | 39 | 31 | 14 | 6 | 14 | 1 |

| 5–8 | 164 | 24 | 42 | 8 | 42 | 12 |

| 9–12 | 156 | 10 | 56 | 10 | 48 | 6 |

| 13–17 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 279 | 25 | 89 | 13 | 83 | 15 |

| Female | 84 | 40 | 23 | 11 | 22 | 4 |

| Location | ||||||

| United States | 163 | 3 | 59 | 1 | 55 | 0 |

| Outside US | 37 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| Unknown | 163 | 62 | 53 | 15 | 42 | 13 |

| Model | AUC Score | F1 Score (MA) |

|---|---|---|

| Eye (Raw) | 0.66 | 0.66 |

| Eye (After) | 0.86 | 0.73 |

| Head (Raw) | 0.66 | 0.66 |

| Head (After) | 0.78 | 0.63 |

| Face (Raw) | 0.63 | 0.69 |

| Face (After) | 0.67 | 0.63 |

| Metric | Eye | Face | Head |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC Score | 0.86 [0.79, 0.92] | 0.67 [0.55, 0.78] | 0.78 [0.69, 0.86] |

| Accuracy | 0.79 [0.72, 0.86] | 0.75 [0.68, 0.82] | 0.75 [0.68, 0.82] |

| Recall (MA) | 0.84 [0.76, 0.91] | 0.65 [0.55, 0.76] | 0.65 [0.55, 0.76] |

| Recall (WA) | 0.79 [0.72, 0.86] | 0.75 [0.68, 0.82] | 0.75 [0.68, 0.82] |

| Precision (MA) | 0.72 [0.65, 0.79] | 0.62 [0.53, 0.70] | 0.62 [0.53, 0.70] |

| Precision (WA) | 0.89 [0.84, 0.92] | 0.79 [0.71, 0.86] | 0.79 [0.71, 0.86] |

| F1 score (MA) | 0.73 [0.65, 0.81] | 0.63 [0.53, 0.71] | 0.63 [0.53, 0.71] |

| F1 score (WA) | 0.82 [0.75, 0.87] | 0.77 [0.69, 0.83] | 0.77 [0.69, 0.83] |

| Metric | Late Fusion (Eye, Head, Face) Averaging | Late Fusion (Eye, Head, Face) Linear | Late Fusion (Eye, Face) Linear |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC Score | 0.90 [0.84, 0.95] | 0.84 [0.77, 0.91] | 0.90 [0.83, 0.95] |

| Accuracy | 0.82 [0.75, 0.89] | 0.84 [0.78, 0.91] | 0.89 [0.83, 0.93] |

| Recall (MA) | 0.88 [0.81, 0.92] | 0.89 [0.82, 0.94] | 0.85 [0.76, 0.93] |

| Recall (WA) | 0.82 [0.75, 0.89] | 0.84 [0.78, 0.91] | 0.89 [0.84, 0.93] |

| Precision (MA) | 0.75 [0.67, 0.82] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.85] | 0.80 [0.72, 0.89] |

| Precision (WA) | 0.90 [0.87, 0.93] | 0.91 [0.88, 0.94] | 0.90 [0.85, 0.94] |

| F1 score (MA) | 0.77 [0.69, 0.85] | 0.79 [0.71, 0.88] | 0.82 [0.74, 0.90] |

| F1 score (WA) | 0.84 [0.78, 0.90] | 0.86 [0.80, 0.92] | 0.89 [0.83, 0.93] |

| Model | Age | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | AUC Score | F1 Score | Demographic Parity Diff. | Equalized Odds Diff. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eye Model | 2–4 | 0.70 [0.50, 0.90] | 0.64 [0.38, 0.87] | 0.90 [0.67, 1.00] | 0.69 [0.44, 0.91] | 0.75 [0.52, 0.92] | 0.21 [0.05, 0.48] | 0.20 [0.10, 0.60] |

| 5–8 | 0.74 [0.62, 0.86] | 0.71 [0.58, 0.85] | 0.97 [0.89, 1.00] | 0.81 [0.69, 0.91] | 0.82 [0.72, 0.91] | |||

| 9–12 | 0.86 [0.77, 0.94] | 0.84 [0.74, 0.93] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 0.94 [0.87, 0.99] | 0.91 [0.85, 0.96] | |||

| Face Model | 2–4 | 0.80 [0.60, 0.95] | 0.79 [0.56, 1.00] | 0.92 [0.73, 1.00] | 0.79 [0.45, 1.00] | 0.85 [0.64, 0.97] | 0.23 [0.02, 0.32] | 0.63 [0.27, 1.00] |

| 5–8 | 0.74 [0.62, 0.86] | 0.76 [0.62, 0.88] | 0.91 [0.81, 1.00] | 0.75 [0.52, 0.94] | 0.83 [0.73, 0.91] | |||

| 9–12 | 0.74 [0.64, 0.83] | 0.84 [0.74, 0.93] | 0.85 [0.75, 0.94] | 0.55 [0.37, 0.72] | 0.85 [0.77, 0.91] | |||

| Head Model | 2–4 | 0.80 [0.60, 0.95] | 0.79 [0.54, 1.00] | 0.92 [0.75, 1.00] | 0.82 [0.61, 0.98] | 0.85 [0.67, 0.97] | 0.23 [0.03, 0.34] | 0.63 [0.27, 1.00] |

| 5–8 | 0.74 [0.60, 0.86] | 0.76 [0.63, 0.88] | 0.91 [0.81, 1.00] | 0.71 [0.49, 0.89] | 0.83 [0.73, 0.92] | |||

| 9–12 | 0.74 [0.64, 0.83] | 0.84 [0.74, 0.93] | 0.85 [0.75, 0.94] | 0.80 [0.68, 0.90] | 0.85 [0.76, 0.91] | |||

| Late Fusion (Average) | 2–4 | 0.75 [0.55, 0.90] | 0.64 [0.33, 0.87] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 0.93 [0.77, 1.00] | 0.78 [0.56, 0.93] | 0.26 [0.04, 0.50] | 0.20 [0.07, 0.53] |

| 5–8 | 0.80 [0.68, 0.90] | 0.79 [0.66, 0.90] | 0.97 [0.90, 1.00] | 0.84 [0.69, 0.95] | 0.87 [0.77, 0.94] | |||

| 9–12 | 0.86 [0.77, 0.94] | 0.84 [0.74, 0.93] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 0.93 [0.85, 0.98] | 0.91 [0.85, 0.96] | |||

| Late Fusion (Linear) | 2–4 | 0.75 [0.55, 0.90] | 0.64 [0.38, 0.89] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 0.64 [0.40, 0.88] | 0.78 [0.55, 0.94] | 0.27 [0.04, 0.51] | 0.21 [0.07, 0.53] |

| 5–8 | 0.84 [0.74, 0.94] | 0.83 [0.71, 0.95] | 0.97 [0.90, 1.00] | 0.85 [0.73, 0.94] | 0.90 [0.82, 0.96] | |||

| 9–12 | 0.88 [0.79, 0.95] | 0.86 [0.76, 0.95] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 0.90 [0.81, 0.96] | 0.92 [0.86, 0.97] | |||

| Late Fusion (Linear, Eye+Face) | 2–4 | 0.95 [0.85, 1.00] | 0.93 [0.77, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 0.93 [0.79, 1.00] | 0.96 [0.87, 1.00] | 0.17 [0.02, 0.22] | 0.38 [0.14, 0.75] |

| 5–8 | 0.84 [0.74, 0.94] | 0.88 [0.78, 0.98] | 0.93 [0.83, 1.00] | 0.85 [0.71, 0.96] | 0.90 [0.83, 0.96] | |||

| 9–12 | 0.91 [0.83, 0.97] | 0.93 [0.85, 0.98] | 0.96 [0.91, 1.00] | 0.93 [0.85, 0.98] | 0.95 [0.90, 0.98] |

| Model | Gender Group | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | AUC Score | F1 Score | Demographic Parity Diff. | Equalized Odds Diff. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eye Model | Female | 0.82 [0.68, 0.94] | 0.78 [0.60, 0.95] | 0.95 [0.83, 1.00] | 0.81 [0.65, 0.95] | 0.86 [0.72, 0.96] | 0.12 [0.00, 0.22] | 0.02 [0.01, 0.32] |

| Male | 0.78 [0.69, 0.86] | 0.76 [0.66, 0.84] | 0.99 [0.95, 1.00] | 0.87 [0.78, 0.93] | 0.86 [0.80, 0.91] | |||

| Face Model | Female | 0.68 [0.53, 0.82] | 0.65 [0.46, 0.84] | 0.83 [0.63, 1.00] | 0.67 [0.44, 0.88] | 0.73 [0.56, 0.86] | 0.29 [0.02, 0.41] | 0.42 [0.16, 0.75] |

| Male | 0.77 [0.69, 0.85] | 0.84 [0.76, 0.91] | 0.89 [0.83, 0.95] | 0.63 [0.48, 0.78] | 0.86 [0.81, 0.92] | |||

| Head Model | Female | 0.68 [0.53, 0.82] | 0.65 [0.45, 0.85] | 0.83 [0.65, 1.00] | 0.70 [0.52, 0.86] | 0.73 [0.57, 0.86] | 0.29 [0.02, 0.41] | 0.42 [0.14, 0.78] |

| Male | 0.77 [0.68, 0.85] | 0.84 [0.76, 0.91] | 0.89 [0.82, 0.95] | 0.76 [0.61, 0.88] | 0.86 [0.80, 0.91] | |||

| Late Fusion (Average) | Female | 0.82 [0.68, 0.94] | 0.74 [0.55, 0.90] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 0.83 [0.65, 0.95] | 0.85 [0.71, 0.96] | 0.21 [0.00, 0.27] | 0.08 [0.01, 0.30] |

| Male | 0.82 [0.74, 0.90] | 0.81 [0.72, 0.89] | 0.99 [0.96, 1.00] | 0.91 [0.83, 0.97] | 0.88 [0.83, 0.93] | |||

| Late Fusion (Linear) | Female | 0.85 [0.74, 0.97] | 0.78 [0.60, 0.93] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 0.79 [0.62, 0.94] | 0.88 [0.76, 0.97] | 0.22 [0.01, 0.25] | 0.08 [0.01, 0.30] |

| Male | 0.84 [0.77, 0.91] | 0.83 [0.74, 0.90] | 0.99 [0.96, 1.00] | 0.87 [0.76, 0.91] | 0.90 [0.85, 0.94] | |||

| Late Fusion (Linear, Eye+Face) | Female | 0.82 [0.68, 0.94] | 0.83 [0.65, 0.96] | 0.90 [0.76, 1.00] | 0.82 [0.65, 0.96] | 0.86 [0.73, 0.96] | 0.21 [0.01, 0.28] | 0.11 [0.04, 0.39] |

| Male | 0.91 [0.85, 0.96] | 0.93 [0.87, 0.98] | 0.96 [0.92, 1.00] | 0.85 [0.81, 0.97] | 0.95 [0.91, 0.98] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huynh, M.A.; Kline, A.; Surabhi, S.; Dunlap, K.; Mutlu, O.C.; Honarmand, M.; Azizian, P.; Washington, P.; Wall, D.P. Ensemble Modeling of Multiple Physical Indicators to Dynamically Phenotype Autism Spectrum Disorder. Algorithms 2025, 18, 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18120764

Huynh MA, Kline A, Surabhi S, Dunlap K, Mutlu OC, Honarmand M, Azizian P, Washington P, Wall DP. Ensemble Modeling of Multiple Physical Indicators to Dynamically Phenotype Autism Spectrum Disorder. Algorithms. 2025; 18(12):764. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18120764

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuynh, Marie Amale, Aaron Kline, Saimourya Surabhi, Kaitlyn Dunlap, Onur Cezmi Mutlu, Mohammadmahdi Honarmand, Parnian Azizian, Peter Washington, and Dennis P. Wall. 2025. "Ensemble Modeling of Multiple Physical Indicators to Dynamically Phenotype Autism Spectrum Disorder" Algorithms 18, no. 12: 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18120764

APA StyleHuynh, M. A., Kline, A., Surabhi, S., Dunlap, K., Mutlu, O. C., Honarmand, M., Azizian, P., Washington, P., & Wall, D. P. (2025). Ensemble Modeling of Multiple Physical Indicators to Dynamically Phenotype Autism Spectrum Disorder. Algorithms, 18(12), 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18120764