Effects of Rare Earth Metals on Steel Microstructures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

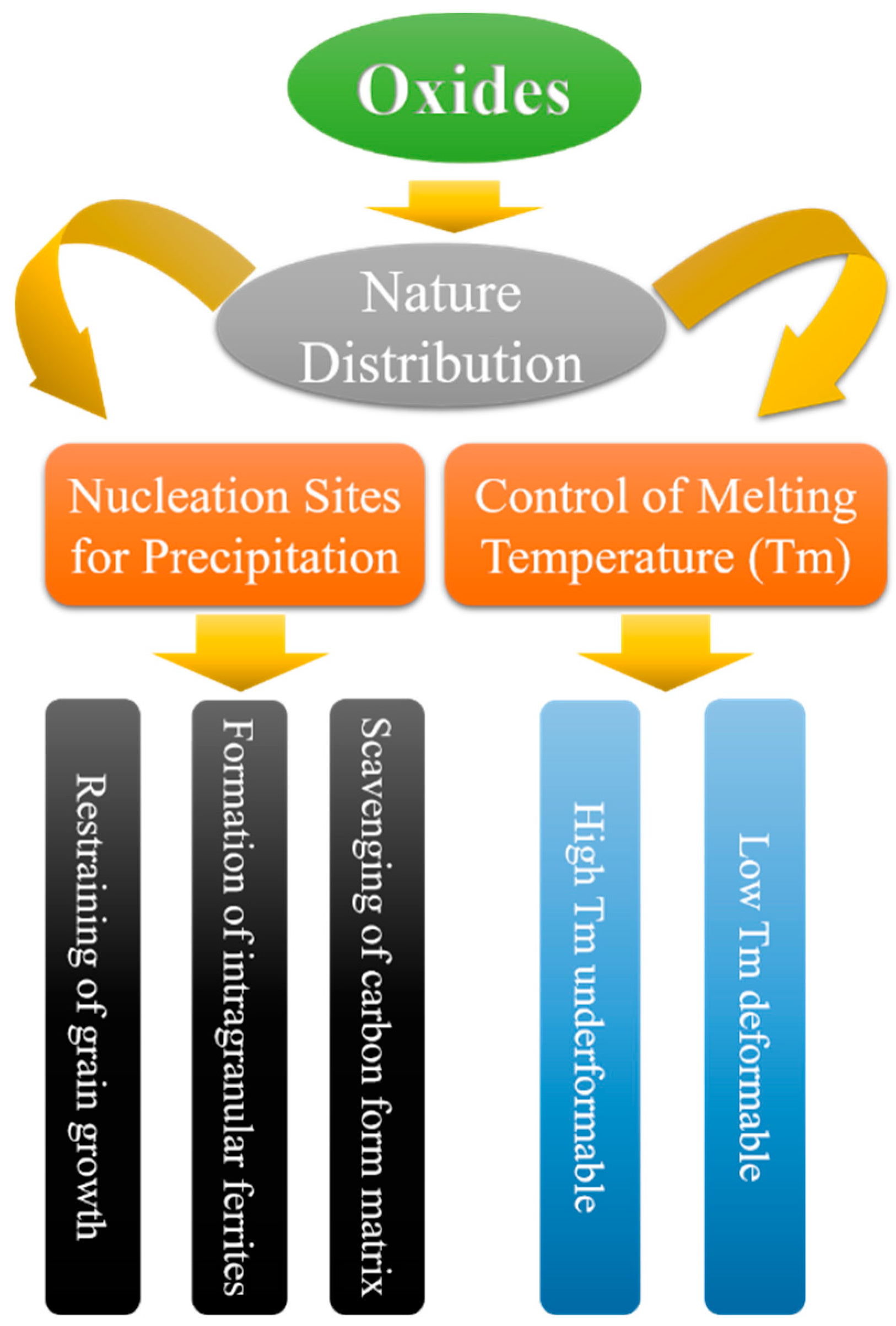

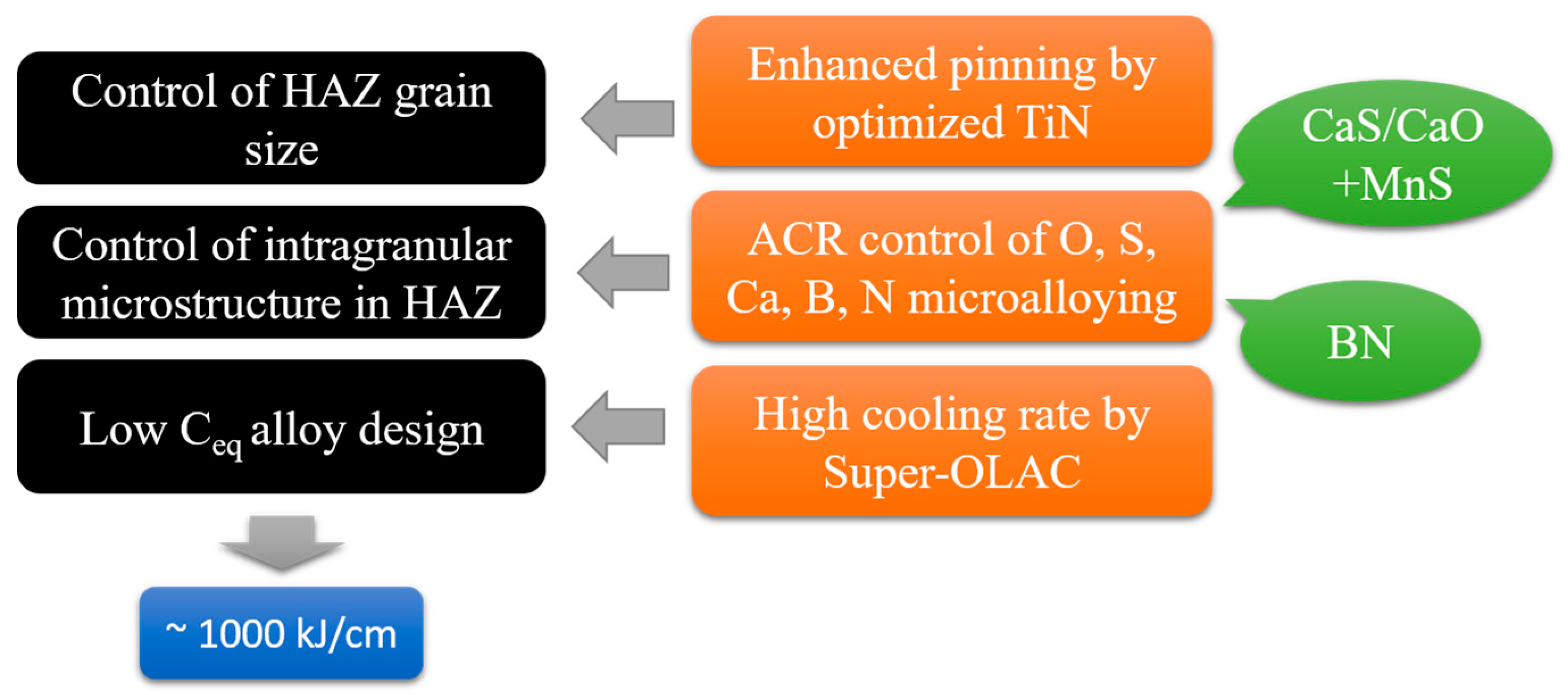

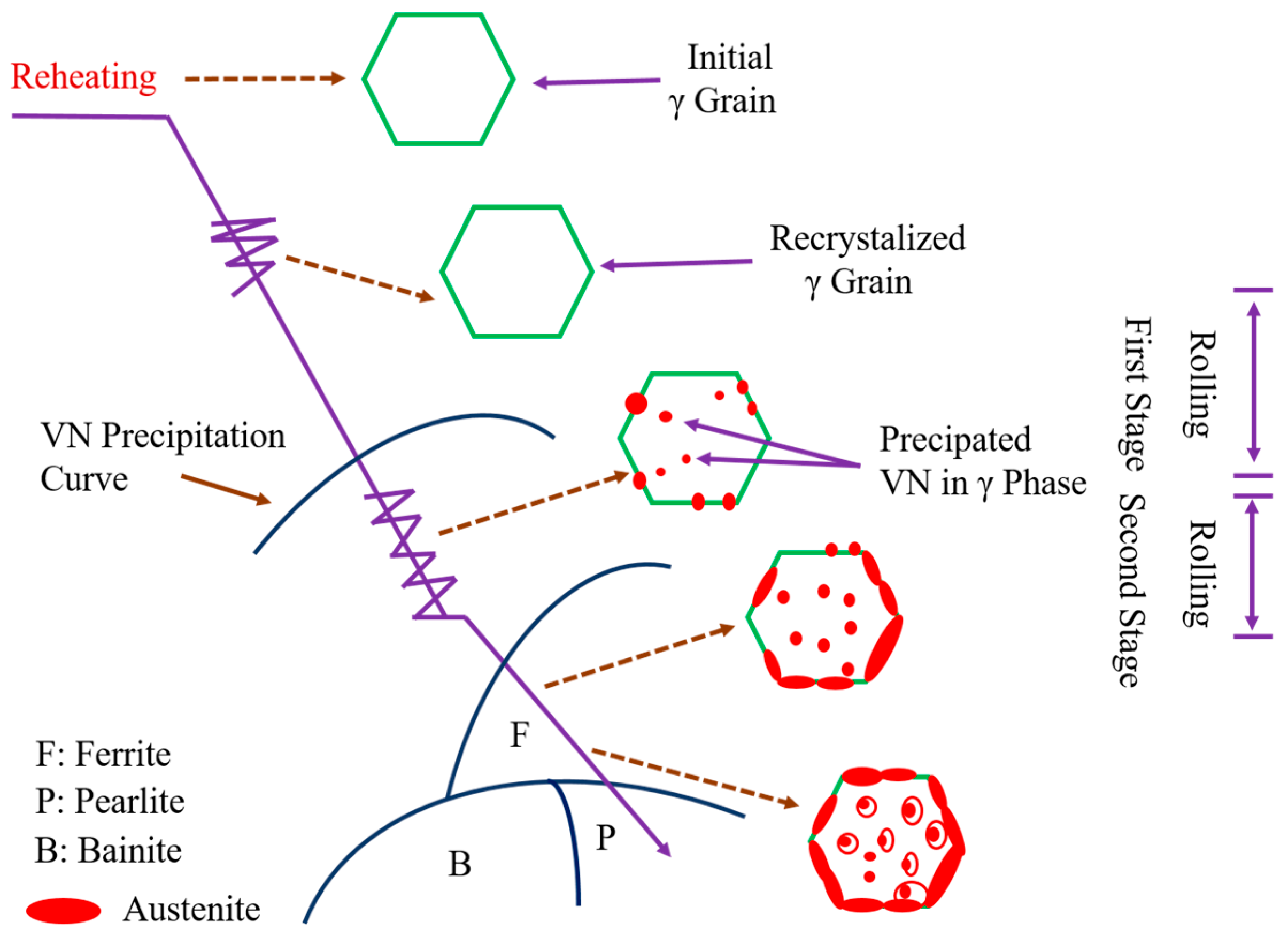

2. Research Background of Oxide Metallurgy

- Controlling the oxide distribution and properties in steel (chemical content, melting point, size, and size distribution).

- Utilizing oxides as the core for heterogeneous nucleation to refine grains and, at the same time, as the core for heterogeneous nucleation of sulfides, nitrides, and carbides to control the segregation distribution of sulfur, nitrogen, and carbon, respectively.

- Suppressing grain growth by pinning the austenitic grain boundary at high temperature with the help of oxides, sulfides, nitrides, and carbide; utilizing the inclusions dissolved in the austenite to affect the transformation from austenite to ferrite and induce intra-grain ferrite; improving the processing properties of steel by forming carbide in the steel substrate.

3. Function of Rare Earth Metals in Steel

3.1. Brief Introduction to Rare Earth Elements

3.2. Function of Cerium in Steel

3.3. Purification of Steel by Using Rare Earth Metals

3.4. Modification of Inclusions

3.5. Micro-Alloying

3.6. Grain Refinement

4. Influence of Rare Earth Metals and Cerium on the Microstructures of Steel

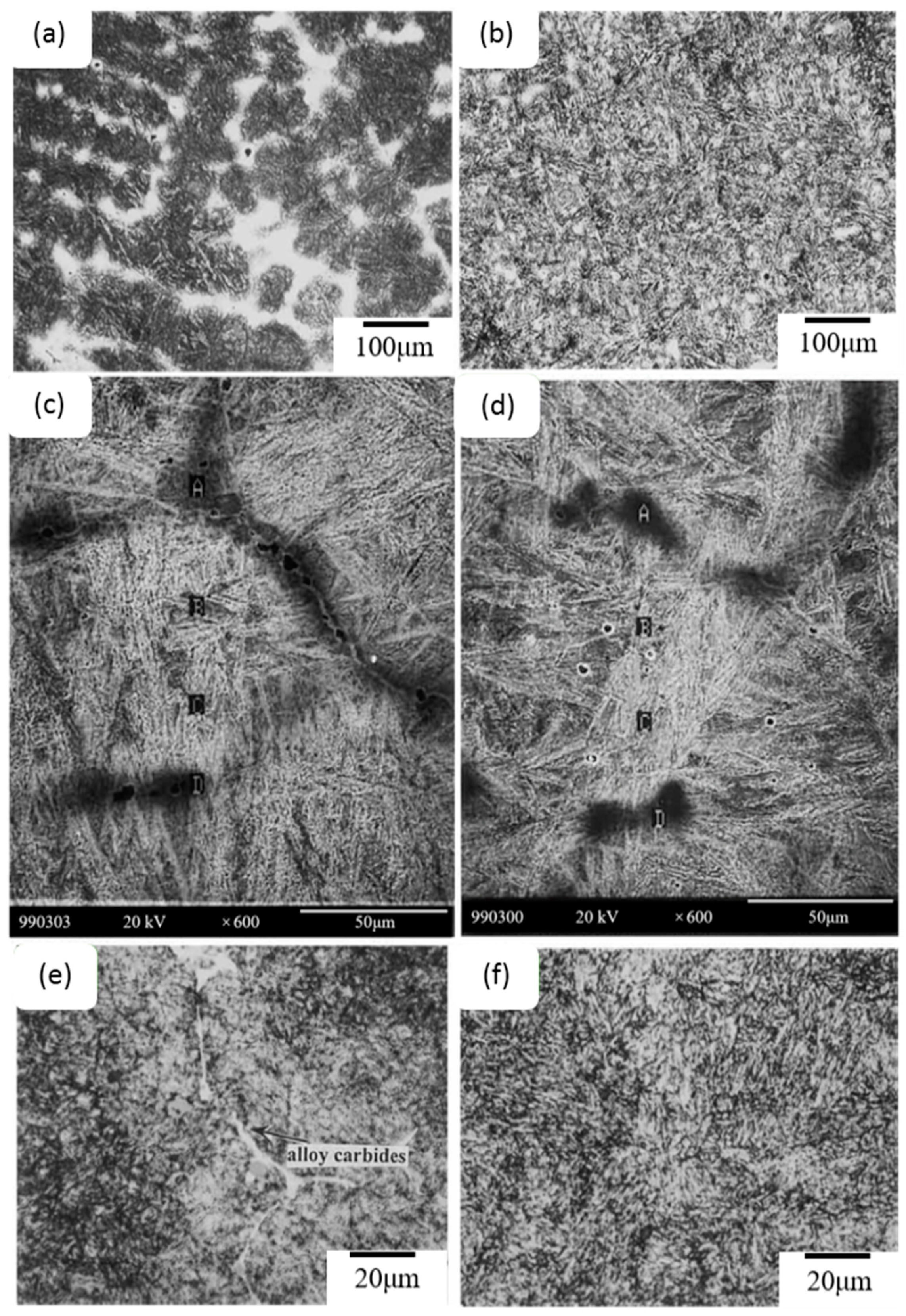

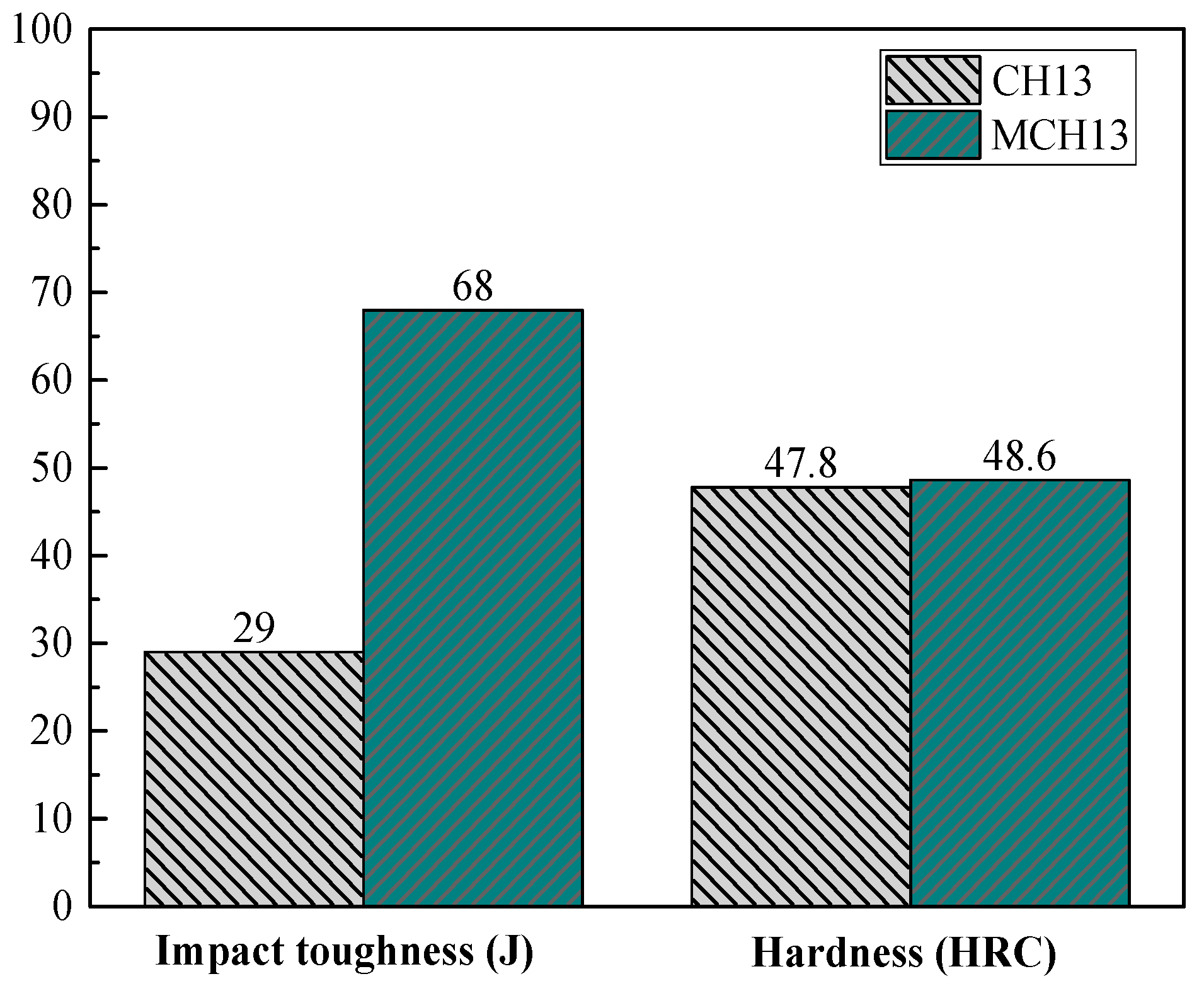

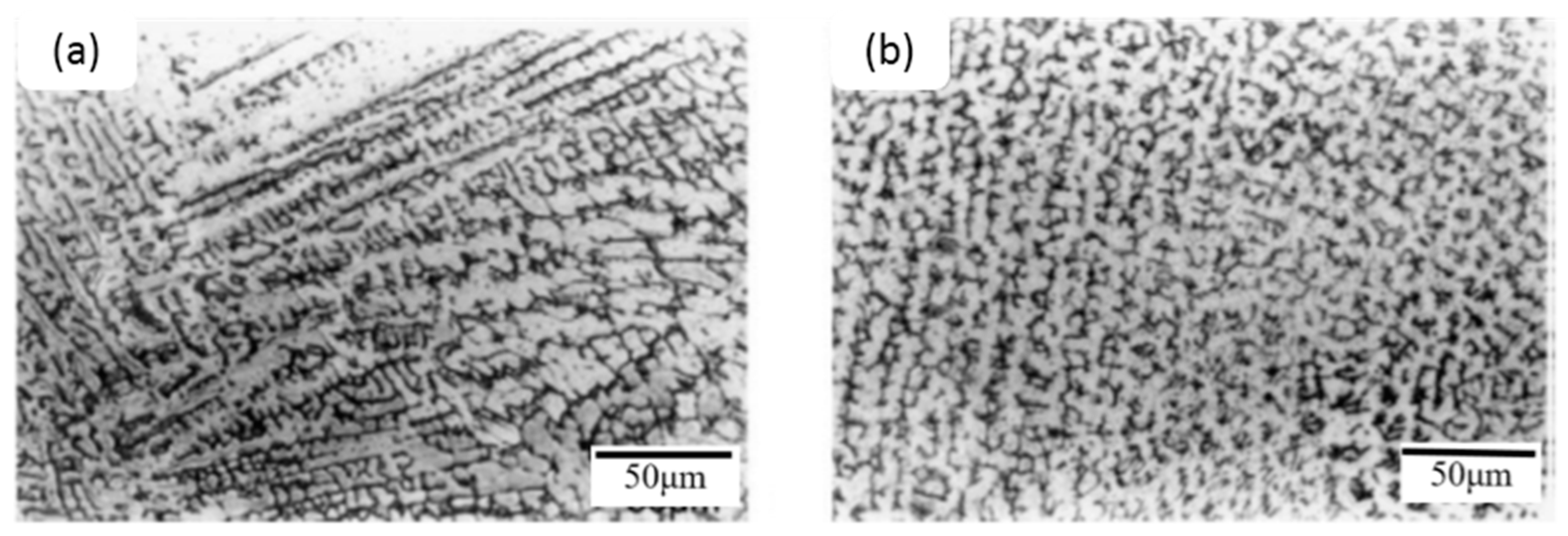

4.1. Effects of Rare Earth Metals on Microstructure of Cast 0.4C–5Cr–1.2Mo–1.0V Steel

4.2. Effects of Rare Earth Metal and Titanium Addition on the Microstructures of Low-Carbon Fe–B Cast Steel

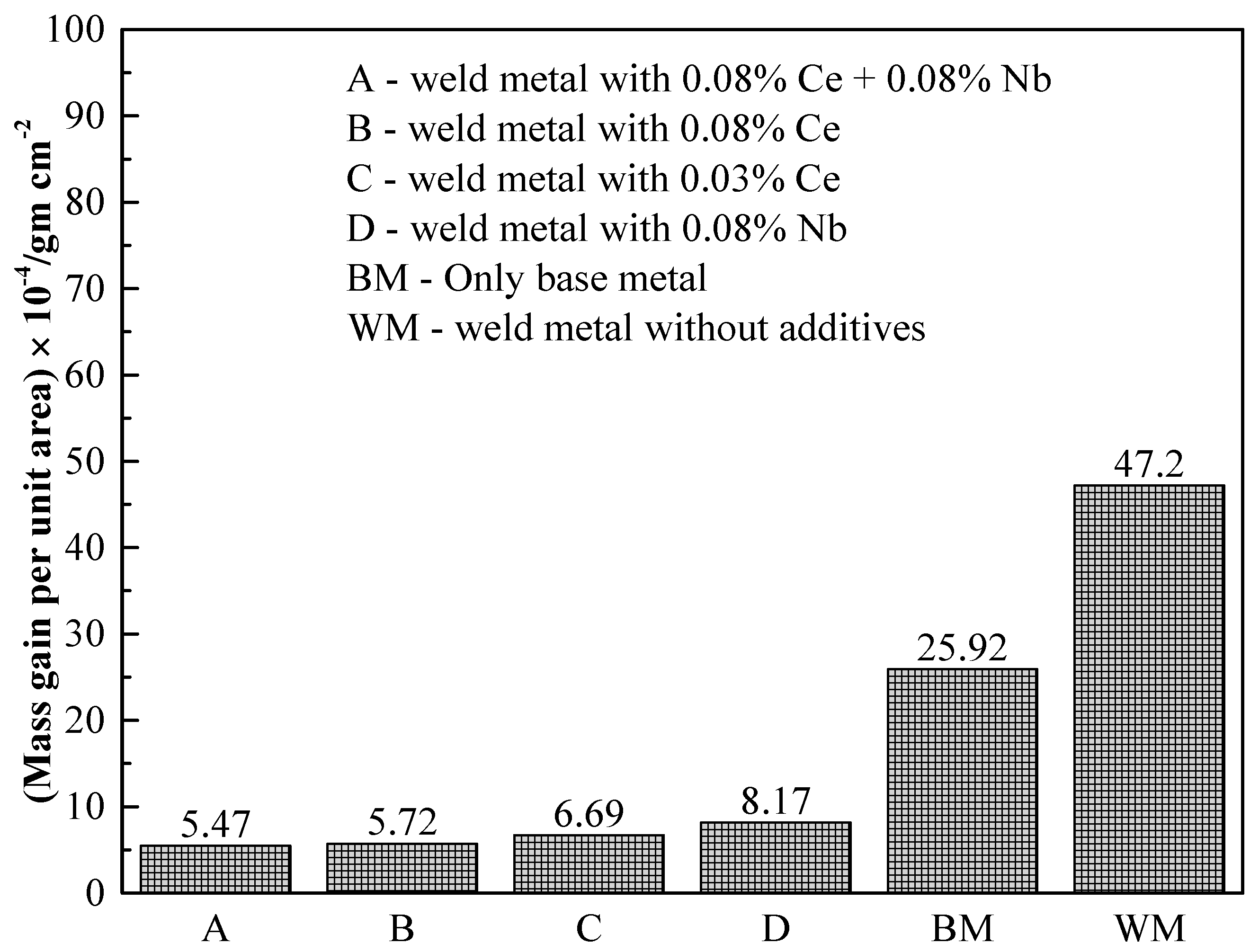

4.3. Effects of Rare Earth Elements on Microstructures in TIG Weldments of AISI 316L Stainless Steel

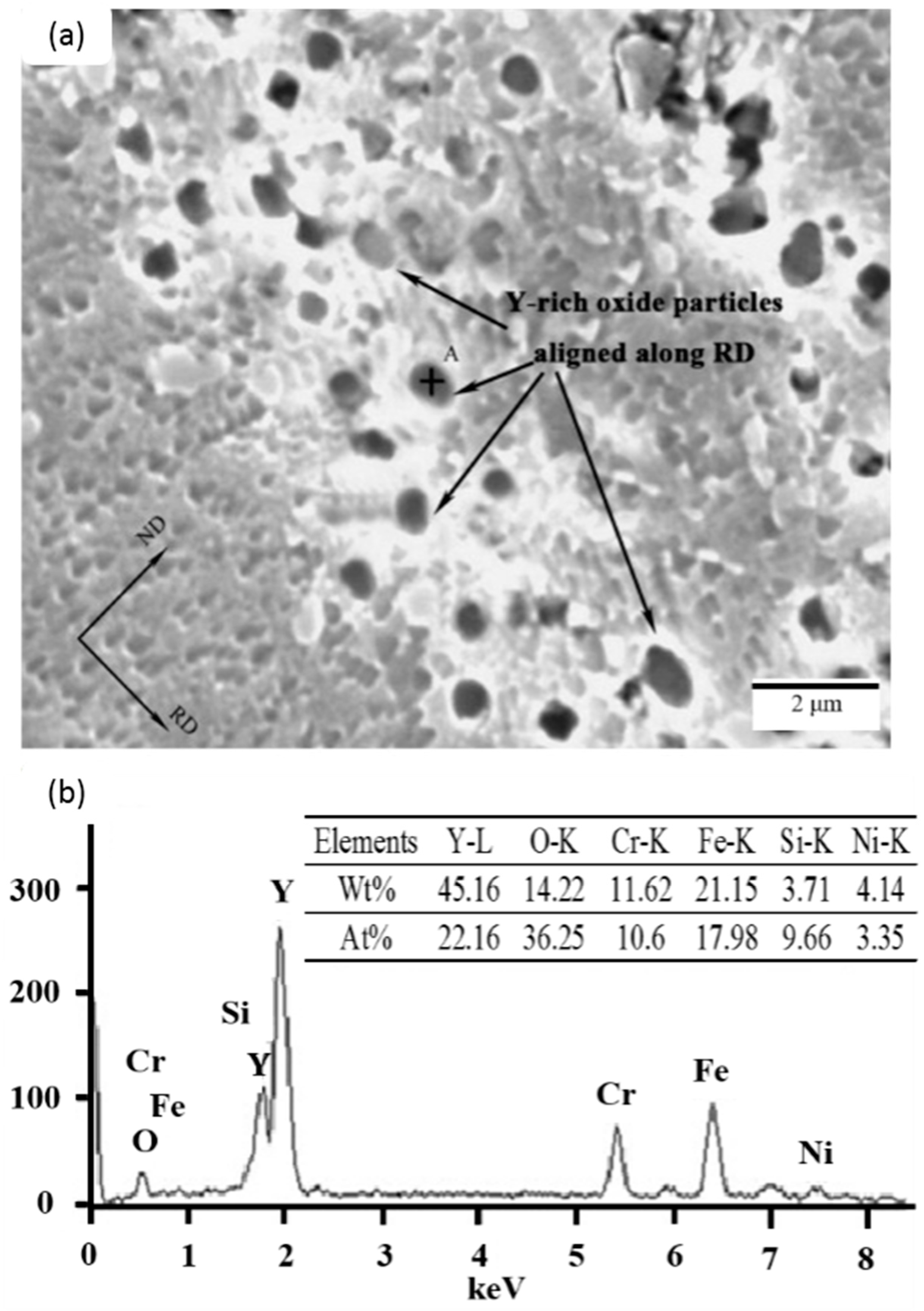

4.4. Effects of Rare Earth Element Yttrium on Microstructures of 21Cr–11Ni Austenitic Heat-Resistant Stainless Steel

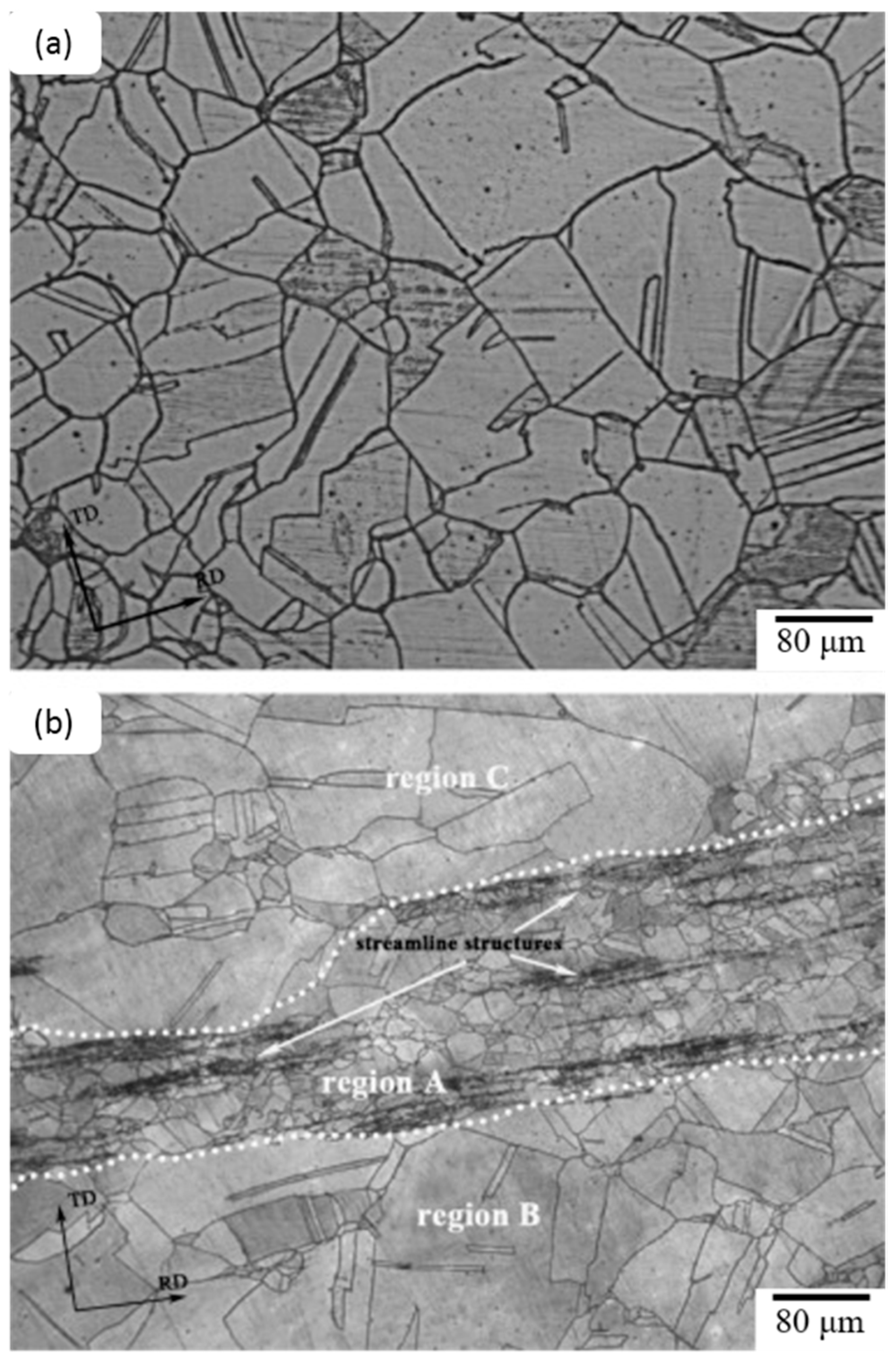

4.5. Effects of Rare Earth Metals on Microstructures of High Speed Steel with High Carbon Content

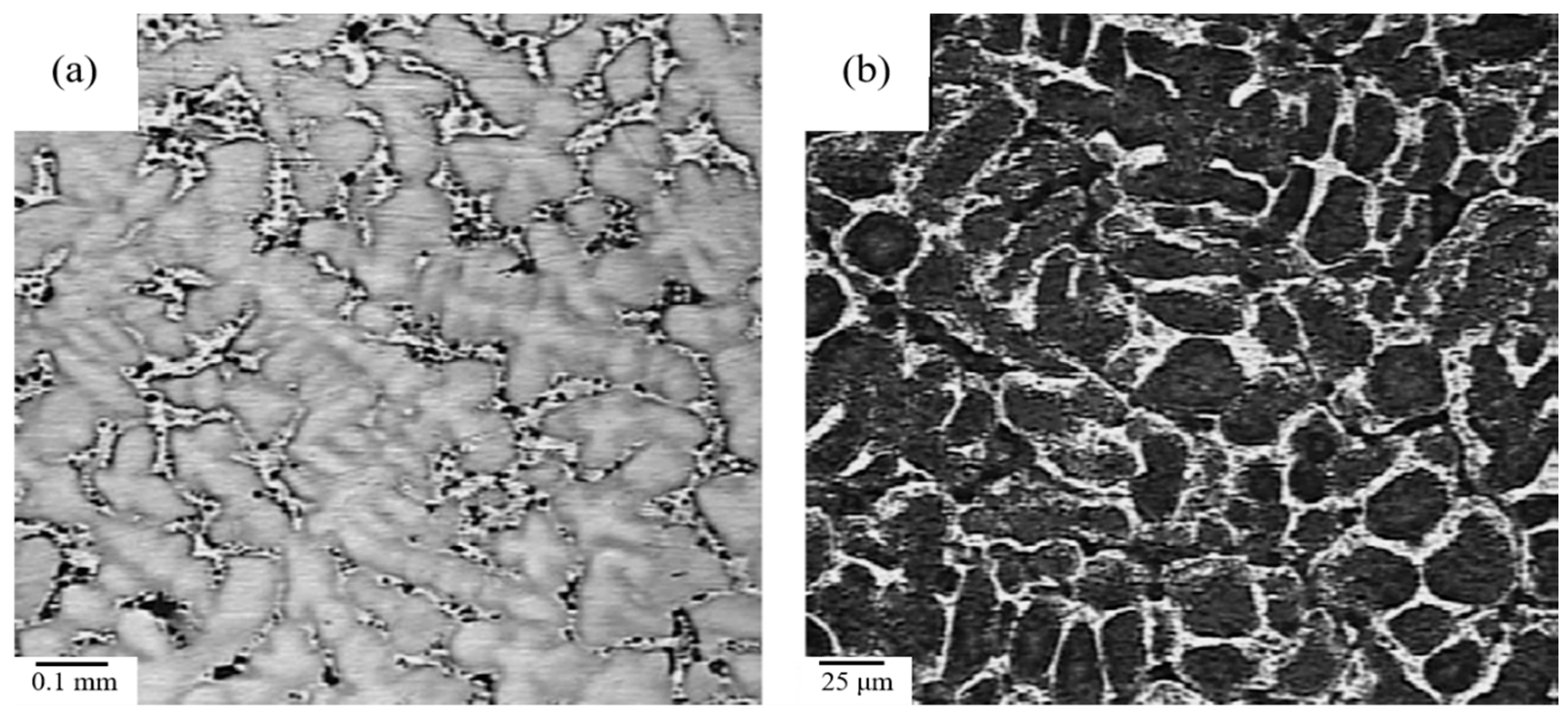

4.6. Effects of Rare Earth Metals on the Microstructures of High-Silicon Cast Steel

4.7. Effects of Rare Earth Metals on the Microstructures of Cast High-Speed Steel Rolls

4.8. Effect of Rare Earth Metals on Microstructures of 17-4PH Steel

5. Conclusions and Future Prospects

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L. Application prospects and behavior of RE in new generation high strength steels with superior toughness. J. Chin. Rare Earth Soc. 2004, 1, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; Peng, P.; Xu, S.; Liu, J. Reasearch and application of rare earth in steel. Res. Stud. Foundry Equip. 2004, 3, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Zi, Y. The application of rare earth in steel. Spec. Steel Technol. 2004, 1, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J. Addition of the rare earth element to steels-an important approach to developing steels in the 21st century. Chin. Rare Earths 2001, 22, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, W.; Fu, J. Steel Metallurgy: Secondary Refining of Oxide Metallurgy; Hop Kee: Taipei, Taiwan, 2012; pp. 217–247. [Google Scholar]

- Satoh, A. Research project on innovative steels in Japan (STX-21 Project). In Proceedings of the Ultra Steel 2000: International Workshop on the Innovative Structural Materials for Infrastructure in 21st Century, Tsukuba, Japan, 12–13 January 2000.

- Weng, Y. New generation of Iron and steel material in China. In Proceedings of the Ultra Steel 2000: International Workshop on the Innovative Structural Materials for Infrastructure in 21st Century, Tsukuba, Japan, 12–13 January 2000.

- Lee, W. Development of high performance structural steels for 21st century in Korea. In Proceedings of the Ultra Steel 2000: International Workshop on the Innovative Structural Materials for Infrastructure in 21st Century, Tsukuba, Japan, 12–13 January 2000.

- Salvatori, I. In European Project on Ultra Fine Grained Steels by Innovative Deformation Cycles. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Advanced Structural Steels, Shanghai, China, 14–16 April 2004.

- Sekine, H.; Maruyama, T.; Kageyama, H.; Kawashima, Y. Grain refinement through hot rolling and cooling after rolling. Thermom. Process. Microalloyed Austenite 1981, 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Y. Steel with Ultra-Fine Grain: Refinement Theory of Steel Structure and Control Technology; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2003; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ogibayashi, S. Advances in technology of oxide metallurgy. Nippon Steel Tech. Rep. 1994, 61, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, D.S.; Karasev, A.; Jönsson, P. On the role of non-metallic inclusions in the nucleation of acicular ferrite in steels. ISIJ Int. 2009, 49, 1063–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricks, R.; Howell, P.; Barritte, G. The nature of acicular ferrite in HSLA steel weld metals. J. Mater. Sci. 1982, 17, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Evaluation of the nucleation potential of intragranular acicular ferrite in steel weldments. Acta Metall. Mater. 1994, 42, 3291–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Farrar, R. Role of non-metallic inclusions in formation of acicular ferrite in low alloy weld metals. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1996, 12, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, H.; Miyazawa, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Ogibayashi, S.; Tanaka, K. Effect of Cooling Rate on Oxide Precipitation during Solidification of Low Carbon Steels. ISIJ Int. 1994, 34, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, H.; Miyazawa, K.; Yamada, W.; Tanaka, K. Effect of cooling rate on composition of oxides precipitated during solidification of steels. ISIJ Int. 1995, 35, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.; Song, B. Intragranular ferrite formation mechanism and mechanical properties of non-quenched-and-tempered medium carbon steels. Steel Res. Int. 2008, 79, 390–395. [Google Scholar]

- Bramfitt, B.L. The effect of carbide and nitride additions on the heterogeneous nucleation behavior of liquid iron. Metall. Trans. 1970, 1, 1987–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.; Shim, J.; Cho, Y.; Lee, D. Non-metallic inclusion and intragranular nucleation of ferrite in Ti-killed C–Mn steel. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 1593–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grong, O.; Matlock, D.K. Microstructural development in mild and low-alloy steel weld metals. Int. Met. Rev. 1986, 31, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkita, S.; Horii, Y. Recent Development in Controlling the Microstructure and Properties of Low Alloy Steel Weld Metals. ISIJ Int. 1995, 35, 1170–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, V.; Ramachandran, S. Rare Earths in Steel Technology. Sci. Technol. Rare Earth Mater. 1980, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Xie, C. Effect of rare earth elements on the erosion resistance of nitrided 40Cr steel. Wear 2003, 254, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Ichimiya, K.; Akita, T. High tensile strength steel plates with excellent HAZ toughness for shipbuilding: JFE EWEL technology for excellent quality in HAZ of high heat input welded joints. JFE Tech. Rep. 2005, 5, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, A.; Kiyose, A.; Uemori, R.; Minagawa, M.; Hoshino, M.; Nakashima, T.; Ishida, K.; Yasui, H. Super high HAZ toughness technology with fine microstructure imparted by fine particles. Shinnittetsu Giho 2004, 90, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Kuwabara, M. Up-to-date progress of technology of oxide metallurgy and its practice. Steelmaking 2007, 23, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Zi, Y. Vitamins in steel—Rare earth metals. Met. World 2004, 1, 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Promising application of rare earths in steel and non-ferrous metals. Rare Earth Inf. 2005, 5, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G. Rare Earths; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 1995; pp. 29–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X. Effect of Rare Earth Metal Cerium on the Texture and Properties of X80 Pipeline Steel. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia University of Science and Technology, Baotou, China, 2 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z. Application of Rare Earths in Steel; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 1984; pp. 23–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. Influence of Y-mg Alloy on Structure and Properties in SS400 Steel. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia University of Science and Technology, Baotou, China, 15 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Waudby, P. Rare earth additions to steel. Int. Met. Rev. 1978, 23, 74–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Ye, W.; Yu, Z. Behavior of rare earths in solid solution in steel. Chin. J. Met. Sci. Technol. 1990, 6, 415–420. [Google Scholar]

- Du, T.; Wang, L. Thermodynamics of Fe-Y-S, Fe-Y-O and Fe-Y-S-O metallic solutions. J. Less Common Met. 1985, 110, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Du, T. Thermodynamics of rare earth elements in liquid iron. J. Less Common Met. 1985, 110, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, F.; Yin, S.; Li, J.; Wang, S. Study on deoxidization thermodynamics of trace rare earth element and formation mechanism of inclusions in LZ50 molten steel. J. Taiyuan Univ. Technol. 2011, 42, 646–649. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Chen, K.; Suo, J.; Chen, F. Effect of rare earth element on desulphurization of steel in continuous casting. Spec. Steel 2001, 22, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Liu, F. Application of rare earth element in steel and its influence on steel properties. Res. Iron Steel 2009, 3, 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Tang, L.; Miao, D.; Sun, W.; Huang, H. Rare earth alloying and its effect on law of precipitation of V and Nb precipitated phase. Res. Iron Steel 2001, 4, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J.; Che, Y.; Liu, A.; Lu, X.; You, M. Research and theory in internal friction of alloying of rare earth in iron and steel. J. Chin. Rare Earth Soc. 1996, 14, 350–359. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Z. A study on rare earth metal microalloying of alloy steel. Spec. Steel 1997, 18, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Hao, K.; Zhou, G.; Wu, H.; Wu, R. Effect of rare-earth on sulfides morphology and abrasive resistance of high sulfur steel. Mater. Mech. Eng. 2012, 36, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Wan, T.; Lou, D. Influence of RE modifier on as-cast grain refinement of super-low carbon cast steel. Spec. Cast. Nonferrous Alloy. 2002, 2, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Fang, L.; Huang, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, C.; Jiang, M. Microstructure of high -carbon RE steel. Chin. Rare Earths 2008, 29, 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, L.; Qin, X.; Sun, X. Effect of cerium on microstructure and hardness of 00Cr17Mo stainless steel. Chin. Rare Earths 2013, 34, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, J.; He, J.; Ding, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, Y. Effect of Rare Earth Metals on the Microstructure and Impact Toughness of a Cast 0.4 C–5Cr–1.2 Mo–1.0 V Steel. ISIJ Int. 2000, 40, 1275–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Xiao, Q.; Kuang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Xing, J.-D. Effect of rare earth and titanium additions on the microstructures and properties of low carbon Fe–B cast steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 466, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Mitra, S.; Pal, T. Effect of rare earth elements on microstructure and oxidation behaviour in TIG weldments of AISI 316L stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 430, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesri, R.; Durand-Charre, M. Phase equilibria, solidification and solid-state transformations of white cast irons containing niobium. J. Mater. Sci. 1987, 22, 2959–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramar, A.; Spätig, P.; Schäublin, R. Analysis of high temperature deformation mechanism in ODS EUROFER97 alloy. J. Nucl. Mater. 2008, 382, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capdevila, C.; Chen, Y.; Lassen, N.K.; Jones, A.; Bhadeshia, H. Heterogeneous deformation and recrystallisation of iron base oxide dispersion strengthened PM2000 alloy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2001, 17, 693–699. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, M.A.; Us Salam, I.; Muhammad, W.; Ejaz, N. Effect of microstructural anisotropy on mechanical behavior of a high-strength Al–Mg–Si Alloy. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2009, 9, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, F.; Ardakani, M. Grain boundary migration and Zener pinning in particle-containing copper crystals. Acta Mater. 1996, 44, 2717–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, P. The effect of deformation on grain growth in Zener pinned systems. Acta Mater. 2001, 49, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ma, X.; Wang, L.; Ye, X. Effect of rare earth element yttrium addition on microstructures and properties of a 21Cr–11Ni austenitic heat-resistant stainless steel. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, P.R.; Siciliano, F., Jr.; Sandim, H.R.Z.; Plaut, R.L.; Padilha, A.F. Nucleation and growth during recrystallization. Mater. Res. 2005, 8, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, I.; Grong, Ø.; Ryum, N. Analytical modelling of grain growth in metals and alloys in the presence of growing and dissolving precipitates—II. Abnormal grain growth. Acta Metall. Mater. 1995, 43, 2689–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, S.; Yamada, K.; Murakami, T.; Narushima, T.; Iguchi, Y.; Ouchi, C. β Grain Refinement due to Small Amounts of Yttrium Addition in. α + β Type Titanium Alloy, SP-700. ISIJ Int. 2006, 46, 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zou, D.; Li, X.; Du, Z. Effect of rare earth on microstructures and properties of high speed steel with high carbon content. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2007, 14, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. Influence of Ce and Al on nodularization of eutectic in austenite–bainite steel. Mater. Res. Bull. 2000, 35, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M. In situ observations of the dissolution of carbides in an Fe-Cr-C alloy. Scr. Mater. 1999, 41, 1301–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dai, T. Relaxational Internal Friction Peak of in a Co-base Superalloy. Acta Metall. Sin. 1986, 22, 441–444. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.-X.; Liao, B.; Liu, J.; Yao, M. Effect of rare earth elements on carbide morphology and phase transformation dynamics of high Ni-Cr alloy cast iron. J. Rare Earths 1998, 16, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y. Fracture toughness improvement of austempered high silicon steel by titanium, vanadium and rare earth elements modification. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 444, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, D.; Cochrane, R. Structure-property relationships in bainitic steels. Metall. Trans. A 1990, 21, 1527–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; He, J.; Ding, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, Y. Study on heterogeneous nuclei in cast H13 steel modified by rare earth. J. Rare Earths 2001, 4, 280–283. [Google Scholar]

- Bhadeshia, H.; Edmonds, D. Bainite in silicon steels: New composition–property approach Part 1. Met. Sci. 1983, 17, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadeshia, H.; Edmonds, D. Bainite in silicon steels: New composition–property approach Part 2. Met. Sci. 1983, 17, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miihkinen, V.; Edmonds, D. Fracture toughness of two experimental high-strength bainitic low-alloy steels containing silicon. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1987, 3, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miihkinen, V.; Edmonds, D. Tensile deformation of two experimental high-strength bainitic low-alloy steels containing silicon. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1987, 3, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miihkinen, V.; Edmonds, D. Microstructural examination of two experimental high-strength bainitic low-alloy steels containing silicon. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1987, 3, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Mu, S.; Sun, F.; Wang, Y. Influence of rare earth elements on microstructure and mechanical properties of cast high-speed steel rolls. J. Rare Earths 2007, 25, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yan, M.; Wu, D. Microstructure and mechanical properties of 17-4PH steel plasma nitrocarburized with and without rare earths addition. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2010, 210, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Sun, Y.; Bell, T.; Liu, Z.; Xia, L. Diffusion of La in plasma RE ion nitrided surface layer and its effect in nitrogen concentration profiles and phase structures. Acta Metall. Sin. 2000, 36, 487–491. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M. Effect of temperature and phase constitution on kinetics of La diffusion. J. Rare Earths 2002, 20, 329–332. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Jung, I.; Oh, K.; Lee, H. Effect of Al on the evolution of non-metallic inclusions in the Mn-Si-Ti-Mg deoxidized steel during solidification: Experiments and thermodynamic calculations. ISIJ Int. 2004, 44, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| State | Density (G/Cm3) | Atomic Diameter (Å) | Electroneg Ativity | Melting Point (°C) | Boiling Point (°C) | Fusion Heat (Kj/Mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gray metal | 8.24 | 1.824 | 1.12 | 798 | 3426 | 5.46 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, F.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.-L.; Su, Y.-H.; Kuo, C.-L.; Su, Y.-H.; Chen, S.-H.; Lin, K.-J.; Hsieh, P.-H.; Hwang, W.-S. Effects of Rare Earth Metals on Steel Microstructures. Materials 2016, 9, 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9060417

Pan F, Zhang J, Chen H-L, Su Y-H, Kuo C-L, Su Y-H, Chen S-H, Lin K-J, Hsieh P-H, Hwang W-S. Effects of Rare Earth Metals on Steel Microstructures. Materials. 2016; 9(6):417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9060417

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Fei, Jian Zhang, Hao-Long Chen, Yen-Hsun Su, Chia-Liang Kuo, Yen-Hao Su, Shin-Hau Chen, Kuan-Ju Lin, Ping-Hung Hsieh, and Weng-Sing Hwang. 2016. "Effects of Rare Earth Metals on Steel Microstructures" Materials 9, no. 6: 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9060417

APA StylePan, F., Zhang, J., Chen, H.-L., Su, Y.-H., Kuo, C.-L., Su, Y.-H., Chen, S.-H., Lin, K.-J., Hsieh, P.-H., & Hwang, W.-S. (2016). Effects of Rare Earth Metals on Steel Microstructures. Materials, 9(6), 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9060417