Recent Progress in Lectin-Based Biosensors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Glucose Sensors

3. Pathogenic Bacteria and Toxin Sensors

4. Cytosensors

5. Lectin Sensing

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scheldon, R.A.; Schoevaart, R.; van Langen, L.M. Cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs): A novel versatile method for enzyme immobilization (a review). Biocatal. Biotransform. 2005, 23, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, S.; Obubuafo, A.; Soper, S.A.; Spivak, D.A. Surface immobilization methods for aptamer diagnostic applications. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 390, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ates, M. A review study of (bio)sensor systems based on conducting polymers. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 1853–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, E.; Willner, I. Amperometric amplification of antigen-antibody association at monolayer interfaces: Design of immunosensor electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1996, 418, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, T.; Saiki, H.; Anzai, J. Preparation of spatially ordered multilayer thin films of antibody and their binding properties. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2000, 15, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilchek, M.; Bayer, E.A. The avidin-biotin complex in bioanalytical applications. Anal. Biochem. 1988, 171, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, D.; Yang, Y.; Chu, X. Synthesis of water-dispersed ferrocene/phenylboronic acid-modified bifunctional gold nanoparticles and the application in biosensing. Materials 2014, 7, 5554–5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Anzai, J. Stimuli-sensitive thin films prepared by a layer-by-layer deposition of 2-iminobiotin-labeled poly(ethyleneimine) and avidin. Langmuir 2005, 21, 8354–8359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzai, J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Takeshita, H.; Chen, Q.; Osa, T.; Hoshi, T.; Du, X. Enzyme sensors prepared by layer-by-layer deposition of enzymes on a platinum electrode through avidin-biotin interaction. Sens. Actuators B 1998, 52, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesta-Claver, J.; Ametis-Cabello, J.; Morales-Sanfrutos, J.; Megia-Fernandez, A.; Valencia-Miron, M.C.; Santoyo-Gonzalez, F.; Capitan-Vallvey, L.F. Electrochemiluminescent disposable cholesterol biosensor based on avidin-biotin assembling with the electroformed luminescent conducting polymer poly(luminol-biotinylated pyrrole). Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 754, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, Y.; Sato, K.; Sugimoto, K.; Anzai, J. Avidin/PSS membrane microcapsules with biotin-binding activity. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 360, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, G.; Ko, H.; Chang, Y.W.; Kang, M.; Ryun, J. Development of SPR biosensor for the detection of human hepatitis B virus using plasma-treated parylene-N film. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 56, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Park, S. Specific detection of avidin-biotin binding using liquid crystal droplets. Colloid Surf. B 2015, 127, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.F.; Palva, P.M.G.; Corella, M.T.S.; Cavalcanti, M.S.M.; Coelho, L.C.B.B. Lectins, versatile protein of recognition: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 1995, 26, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.W.; Reeke, G.N., Jr.; Cunninngham, B.A.; Edelman, G.M. New evidence on the location of the saccharide-binding site of concanavalin A. Nature 1976, 259, 406–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandel, D.K.; Kishore, N.; Brewer, C.F. Thermodynamics of lectin-carbohydrate interactions. Titration microcalorimetry measurements of the binding of N-linked carbohydrates and ovalbumin to concanavalin A. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Z.; Zhao, F.L.; Li, K.A.; Tong, S.Y. A study on the interaction between concanavalin A and glycogen by light scattering technique and its analytical application. Talanta 2001, 54, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

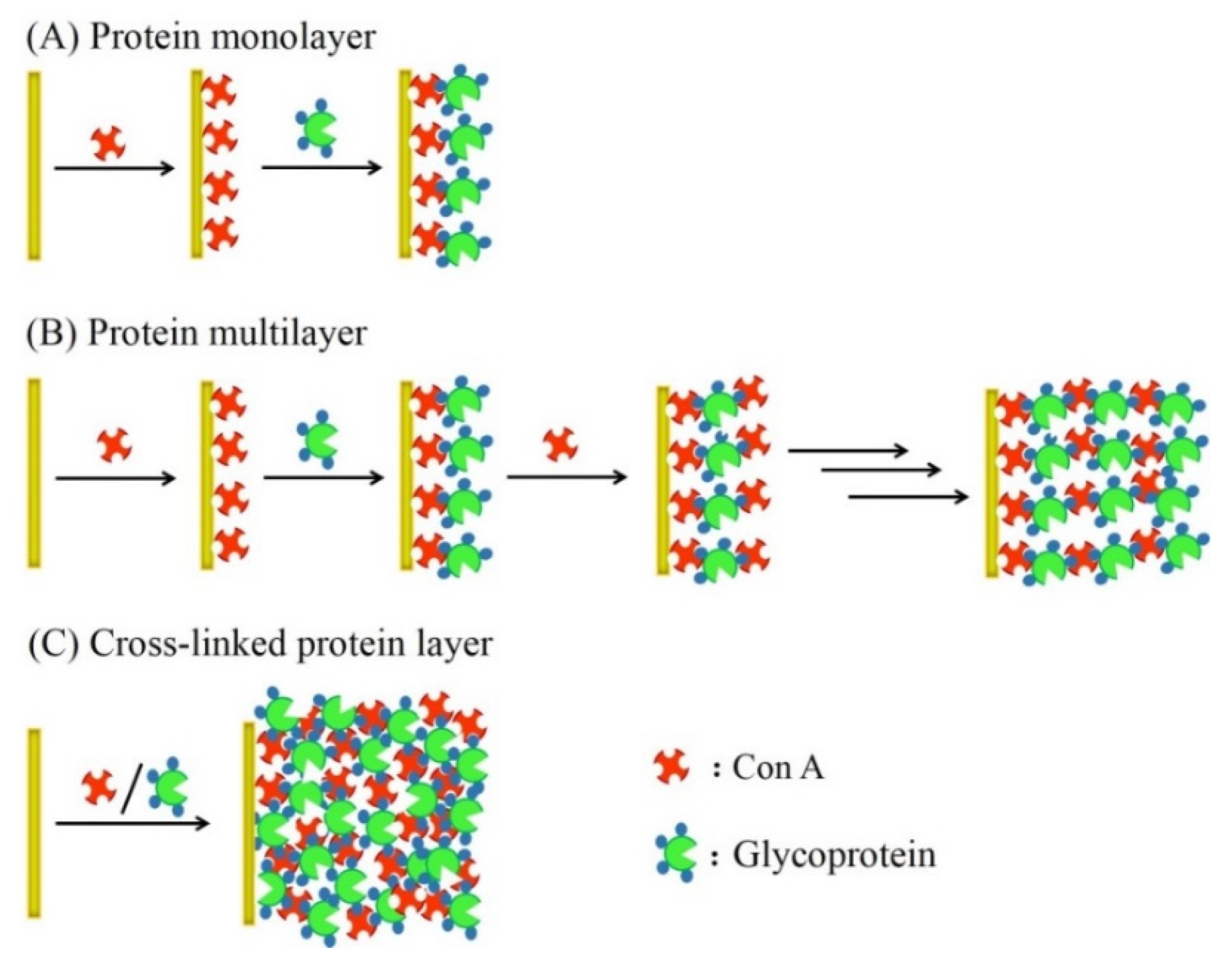

- Hoshi, T.; Akase, S.; Anzai, J. Preparation of multilayer thin films containing avidin through sugar-lectin interactions and their binding properties. Langmuir 2002, 18, 7024–7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Imoto, Y.; Sugama, J.; Seki, S.; Inoue, H.; Odagiri, T.; Hoshi, T.; Anzai, J. Sugar-induced disintegration of layer-by-layer assemblies composed of concanavalin A and glycogen. Langmuir 2005, 21, 797–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballerstadt, R.; Evans, C.; McNichols, R.; Gowda, A. Concanavalin A for in vivo glucose sensing: A biotoxicity review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006, 22, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzai, J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Hoshi, T.; Saiki, H. A layer-by-layer deposition of concanavalin A and native glucose oxidase to form multilayer thin films for biosensor applications. Chem. Lett. 1999, 28, 365–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzai, J.; Kobayashi, Y. Construction of multilayer thin films of enzymes by means of sugar-lectin interactions. Langmuir 2000, 16, 2851–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, T.; Saiki, H.; Kuwazawa, S.; Tsuchiya, C.; Chen, Q.; Anzai, J. Selective permeation of hydrogen peroxide through polyelectrolyte multilayer films and its use for amperometric biosensors. Anal. Chem. 2001, 73, 5310–5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Anzai, J. Preparation and optimization of bienzyme multilayer films using lectin and glyco-enzymes for biosensor applications. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2001, 507, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; Turner, A.P.F. Glucose oxidase: An ideal enzyme. Biosens. Bioelectron. 1992, 7, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, P.P.; Moraes, M.L.; Volpati, D.; Miranda, P.B.; Oliveira, O.N., Jr.; Ferreira, M. Amperometric detection of lactose using β-galactosidase immobilized in layer-by-layer films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 11657–11664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Yoshida, K.; Takahashi, S.; Anzai, J. pH- and sugar-sensitive layer-by-layer films and microcapsules for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Hasebe, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Sato, K.; Anzai, J. Layer-by-layer deposited nano- and micro-assemblies for insulin delivery: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 34, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolls, K.M.; Cheng, F.; Burk-Rafel, J.; Dubey, M.; Ratner, D.M. Imaging analysis of carbohydrate-modified surfaces using Tof-SIMS and SPRi. Materials 2010, 3, 3948–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díez-Pascual, A.M.; Shuttleworth, P.S. Layer-by-layer assembly of biopolyelectrolytes onto thermos/pH-responsive micro/nano-gels. Materials 2014, 7, 7472–7512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanakis, A.; Heise, A. Thermoresponsive glycopolypeptides with temperature controlled selective lectin binding properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 69, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Kodama, D.; Anzai, J. Electrochemical determination of sugars by use of multilayer thin films of ferrocene-appended glycogen and concanavalin A. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 6, 1899–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, M.; Duerkop, A.; Wolfbeis, O.S. Optical methods for sensing glucose. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 4805–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Takahashi, S.; Anzai, J. Layer-by-layer thin films and microcapsules for biosensors and controlled release. Anal. Sci. 2012, 28, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Andrade, C.A.S.; Oliveira, M.D.L.; Sun, X. Carbohydrate-protein interactions and their biosensing applications. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 3161–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Sato, K.; Anzai, J. Layer-by-layer construction of protein architectures through avidin-biotin and lectin-sugar interactions for biosensor applications. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 1749–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wei, L.; Fang, P.; Yang, P. Recent advances in the fabrication and detection of lectin microarrays and their application in glycobiology analysis. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xie, Q.; Yang, D.; Xiao, H.; Fu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Yao, S. Recent advances in electrochemical glucose biosensors: A review. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 4473–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Prestgard, M.; Tiwari, A. A review of recent advances in nonenzymatic glucose sensors. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 41, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Anzai, J. Phenylboronic acid monolayer-modified electrodes sensitive to sugars. Langmuir 2005, 21, 5102–5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palod, P.A.; Singh, V. Improvement in glucose biosensing response of electrochemically grown polypyrrole nanotubes by incorporating crosslinked glucose oxidase. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 55, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egawa, Y.; Seki, T.; Takahashi, S.; Anzai, J. Electrochemical and optical sugar sensors based on phenylboronic acid and its derivatives. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2011, 31, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ҫiftҫi, H.; Tamer, U. Functional gold nanorod particles on conducting polymer poly(3-octylthiophene) as non-enzymatic glucose sensor. React. Funct. Polym. 2012, 72, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Anzai, J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Nakamura, N.; Hoshi, T. Use of Con A and mannose-labeled enzymes for the preparation of enzyme films for biosensors. Sens. Actuators B 2000, 65, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, G.; Colafemmina, G.; Iudice, C.G.; Mallardi, A. Three immobilized enzymes acting in series in layer by layer assemblies: Exploiting the trehalase-glucose oxidase-horseradish peroxidase cascade reactions for the optical determination of trehalose. Sens. Actuators B 2014, 202, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ou, X.; Lu, Q.; Chen, S.; Wei, S. A biorecognition system for concanavalin a using a glassy carbon electrode modified with silver nanoparticles, dextran and glucose oxidase. Microchim. Acta 2015, 182, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B. A stable enzyme biosensor using concanavalin a complex of glucose oxidase for glucose determination. Anal. Lett. 1998, 31, 2349–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, R.; Pishko, M.V.; Gefrides, C.C.; McShane, M.J.; Coté, G.L. A fluorescence-based glucose biosensor using concanavalin A and dextran encapsulated in a poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogel. Anal. Chem. 1999, 71, 3126–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Hoshi, T.; Anzai, J. Glucose and lactate biosensors prepared by a layer-by-layer deposition of concanavalin A and mannose-labeled enzymes: Electrochemical response in the presence of electron mediators. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 49, 755–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnayelka, S.; McShene, M.J. Glucose-sensitive nanoassemblies comprising affinity-binding complexes trapped in fuzzy microshells. J. Fluoresc. 2004, 14, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickup, J.C.; Hussain, F.; Evans, N.D.; Rolinski, O.J.; Birch, D.J.S. Fluorescence-based glucose sensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2005, 20, 2555–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Wang, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhang, S. A simple strategy for one-step construction of bienzyme biosensor by in-situ formation of biocomposite film through electrodeposition. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 24, 3030–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Yuan, R.; Chai, Y. Determination of glucose using pseudobienzyme channeling based on sugar-lectin biospecific interactions in a novel organic-inorganic composite matrix. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 21397–21404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yuan, R.; Chai, Y.; Zhong, H.; Wang, Y. Study of the biosensor based on platinum nanoparticles supported on carbon nanotubes and sugar-lectin biospecific interactions for the determination of glucose. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 4203–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Yuan, R.; Chai, Y. Synthesis of chitosan-Prussian blue-graphene composite nanosheets for electrochemical detection of glucose based on pseudobienzyme channeling. Sens. Actuators B 2012, 162, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Yuan, D.; Zhong, X. Amperometric glucose biosensor based on glucose oxidase-lectin biospecific interaction. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2013, 52, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Xi, F.; Yang, S.; Wu, Q.; Lin, X. Development of a bienzyme system based on sugar-lectin biospecific interactions for amperometric determination of phenols and aromatic amines. Sens. Actuators B 2008, 130, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, Z.; Yang, S.; Jin, X.; Lin, X. A novel inhibition biosensor constructed by layer-by-layer technique based on biospecific affinity for the determination of sulfide. Sens. Actuators B 2008, 129, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

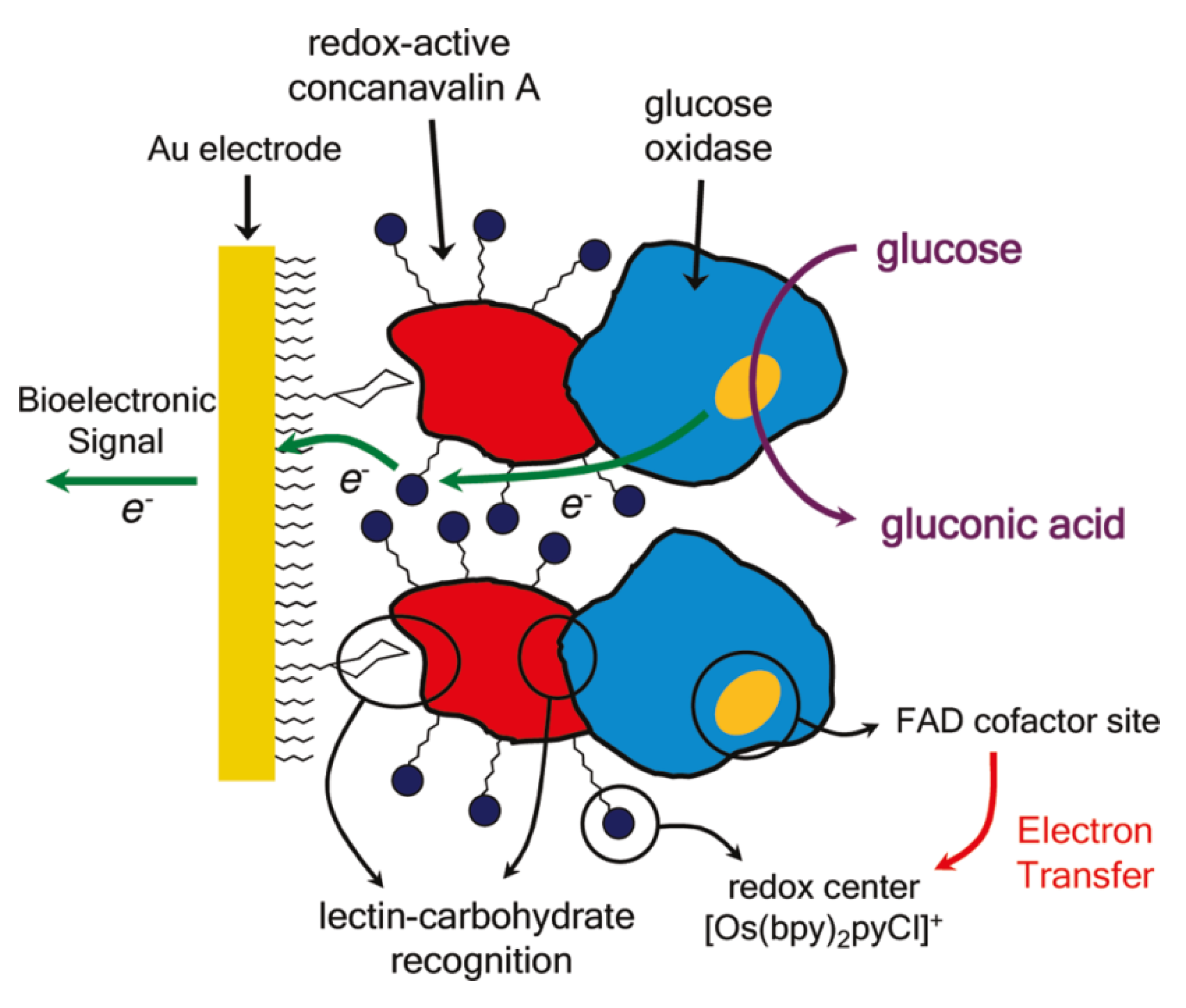

- Pallarola, D.; Queralto, N.; Knoll, W.; Ceolín, M.; Azzaroni, O.; Battaglini, F. Redox-active concanavalin A: Synthesis, characterization, and recognition-driven assembly of interfacial architectures for bioelectronics application. Langmuir 2010, 26, 13684–13696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortez, M.L.; Pallarola, D.; Ceolín, M.; Azzaroni, O.; Battaglini, F. Ionic self-assembly of electroactive biorecognizable units: Electrical contacting of redox glycoenzymes made easy. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 10868–10870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallarola, D.; von Bildering, C.; Pietrasanta, L.I.; Queralto, N.; Knoll, W.; Battaglini, F.; Azzaroni, O. Recognition-driven layer-by-layer construction of multiprotein assemblies on surfaces: A biomolecular toolkit for building up chemoresponsive bioelectrochemical interfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 11027–11039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortez, M.L.; Pallarola, D.; Ceolín, M.; Azzaroni, O.; Battaglini, F. Electron transfer properties of dual self-assembled architectures based on specific recognition and electrostatic driving forces: Its application to control substrate inhibition in horseradish peroxidase-based sensors. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 2414–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, K.; Yugami, A.; Kadoya, T.; Hosaka, K. Electrochemically monitoring the binding of cancanavalin A and ovalbumin. Talanta 2011, 85, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhao, X.; Ma, L.; Zhou, Q. Oriented immobilization of glucose oxidase on graphene oxide. Biochem. Eng. J. 2012, 69, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.A.; Husain, Q. Immobilization of Kluyveromyces lactis β galactosidase on concanavalin A layered aluminum oxide nanoparticles—Its future aspects in biosensor applications. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2011, 70, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Hu, N. pH-switchable bioelectrocatalysis of hydrogen peroxide on layer-by-layer films assembled by cancanavalin A and horseradish peroxidase with electroactive mediator in solution. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 3380–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Ramirez, P.; Tahir, M.N.; Made, S.; Siwy, Z.; Neumann, R.; Tremel, W.; Ensinger, W. Biomolecular conjugation inside synthetic polymer nanopores via glycoprotein-lectin interactions. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 1894–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, L. A novel tri-protein bio-interphase composed of cytochrome c, horseradish peroxides and concanavalin A: Electron transfer and electrocatalytics. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2012, 7, 11206–11218. [Google Scholar]

- Labib, M.; Hedström, M.; Amin, M.; Mattiasson, B. A novel competitive capacitive glucose biosensor based on concanavalin A-labeled nanogold colloids assembled on a polytyramine-modified gold electrode. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 659, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Feng, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, L.; Tang, C.; Tang, B. A selective novel non-enzyme glucose amperometric biosensor based on lectin-sugar binding on thionine modified electrode. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 2489–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hou, T.; Li, W.; Chen, M.; Li, F. Highly sensitive and selective electrochemical identification of D-glucose based on specific concanavalin A combined with gold nanoparticles signal amplification. Sens. Actuators B 2013, 185, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

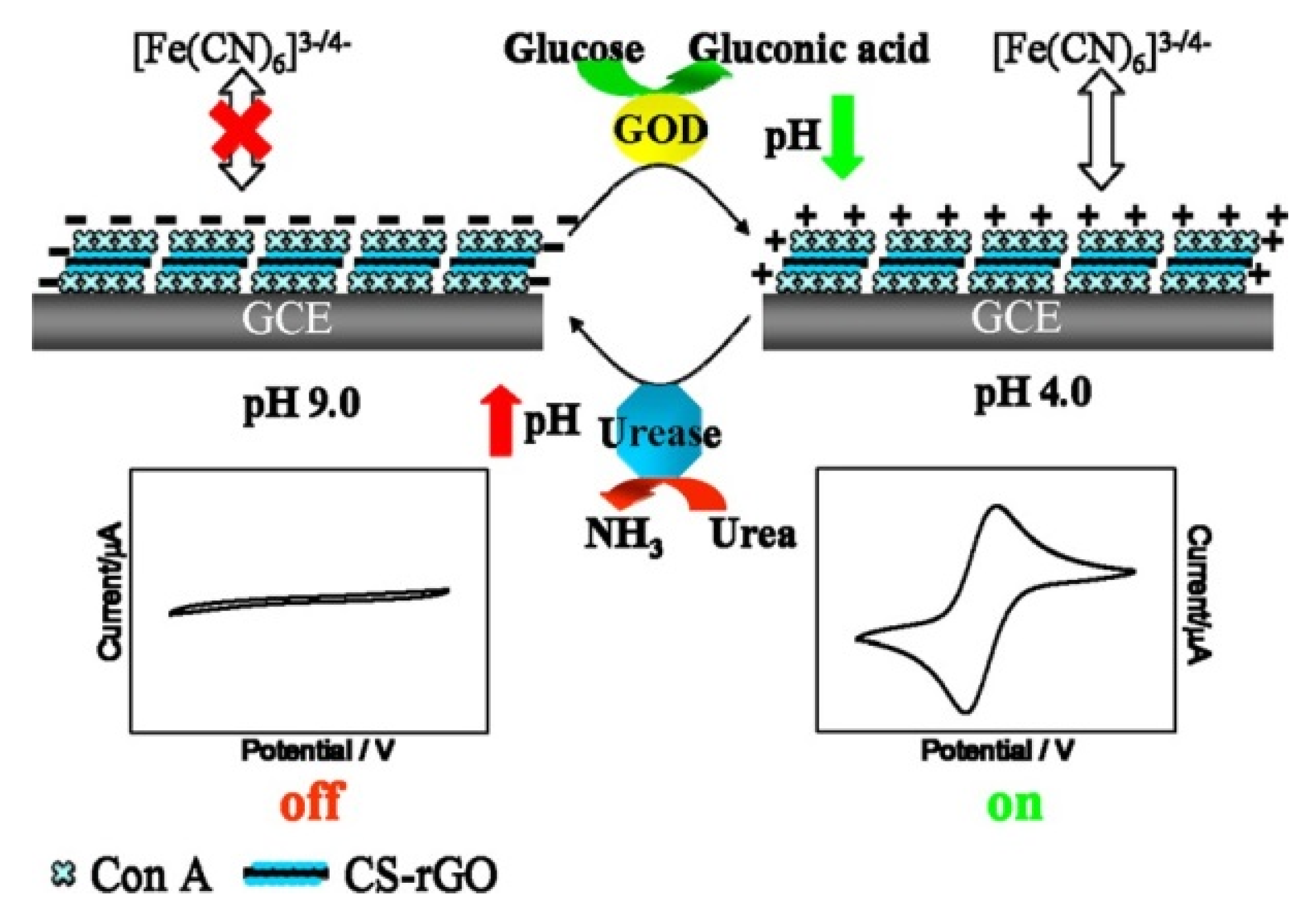

- Song, Y.; Liu, H.; Tan, H.; Xu, F.; Jia, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, L. pH-switchable electrochemical sensing platform based on chitosan-reduced graphene oxide/concanavalin A layer for assay of glucose and urea. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 1980–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, K.R.; Park, J.; Choi, H.N.; Lee, W. Gold glyconanoparticle-based colorimetric bioassay for the determination of glucose in human serum. Microchem. J. 2013, 106, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Chen, M.; Chen, M.; Wang, J. The inhibition of fluorescence resonance energy transfer between quantum dots for glucose assay. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 32, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paek, S.; Cho, I.; Kim, D.; Jeon, J.; Lim, G.; Paek, S. Label-free, needle-type biosensor for continuous glucose monitoring based on competitive binding. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 40, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Li, Q.; Tang, J.; Su, B.; Chen, G. An enzyme-free quartz crystal microbalance biosensor for sensitive glucose detection in biological fluids based on glucose/dextran displacement approach. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 686, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulibaly, F.S.; Youan, B.C. Concanavalin A—Polysaccharides binding affinity analysys using a quartz crystal microbalance. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 59, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Huang, M.J.; Ang, J.J.; Yao, Q.; Ning, Y. Label-free detection of carbohydrate—Protein interactions using nanoscale field effect transistor biosensors. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 4392–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, J.K.; Sharma, A.; Fujikawa, K.; Demchenko, A.V.; Stine, K.J. Electrochemical synthesis of nanostructured gold film for the study of carbohydrate—Lectin interactions using localized surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy. Carbohyd. Res. 2015, 405, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.M.; Domngues, L. On the track for an efficient detection of Escherichia coli in water: A review on PCR-based methods. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 113, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, K.G.; Falkenhorst, G.; Ceper, T.; Dalby, T.; Etchelberg, S.; Mølbak, K.; Krogfelt, K.A. Detection of antibodies to Campylobacter in humans using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay: A review of the literature. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 74, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamella, M.; Campuzano, S.; Parrado, C.; Reviejo, A.J.; Pingarrón, J.M. Microorganisms recognition and quantification by lectin adsorptive affinity impedance. Talanta 2009, 78, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.Y.; Ye, W.W.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, L.D.; Leung, P.H.M.; Li, Y.; Yang, M. Ultrasensitive detection of E. coli O157:H7 with biofunctional magnetic bead concentration via nanoporous membrane based electrochemical immunosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 41, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

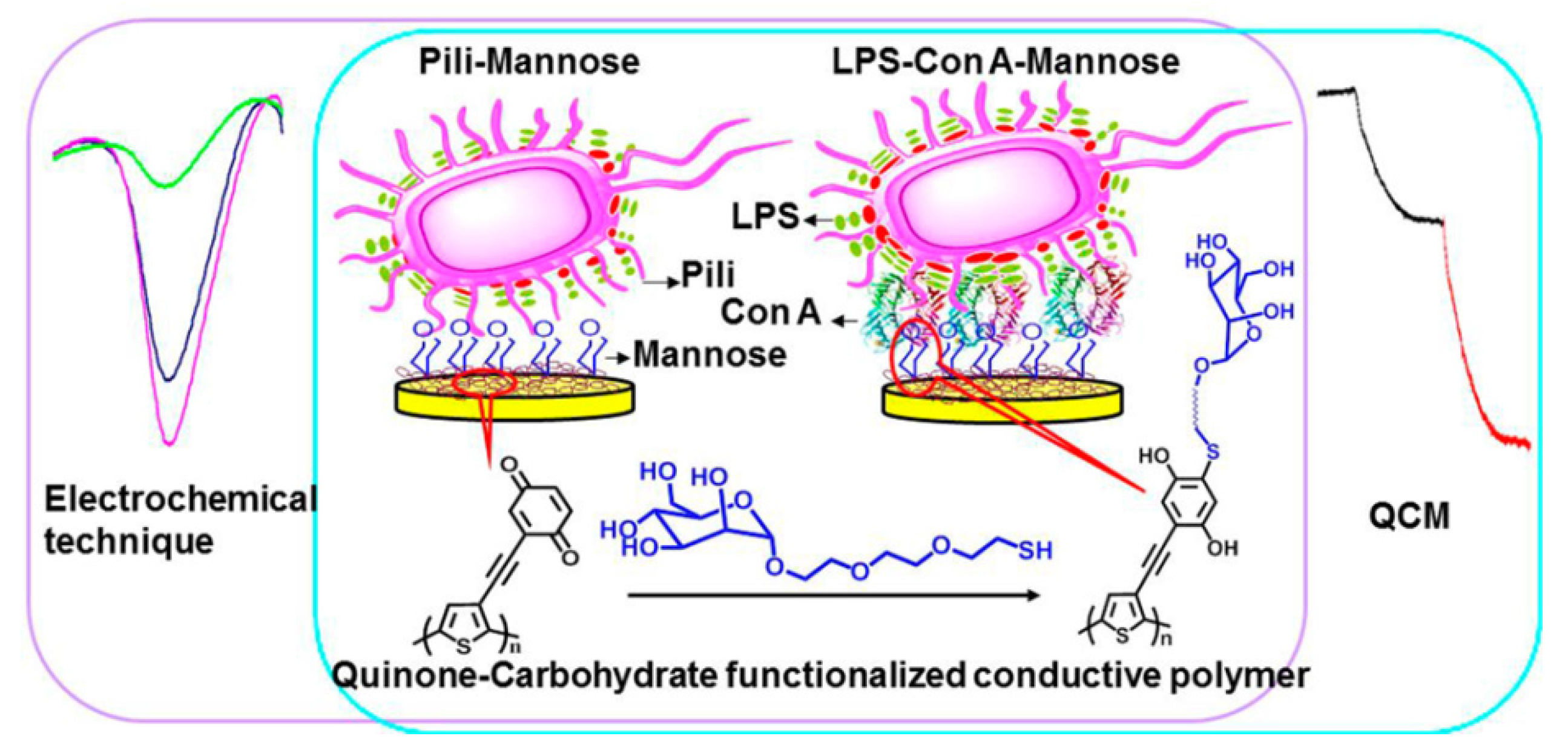

- Ma, F.; Rehman, A.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, S.; Zeng, X. Glycosylation on quinine-fused polythiophene for reagentless and label-free detection of E. coli. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 1560–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dechtrirat, D.; Gajovic-Eichelmann, N.; Wojcik, F.; Hartmenn, L.; Bier, F.F.; Scheller, F.W. Electrochemical displacement sensor based on ferrocene boronic acid tracer and immobilized glycan for saccharide binding proteins and E. coli. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 58, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springsteen, G.; Wang, B. A detailed examination of boronic acid-diol complexation. Tetrahedron 2001, 58, 5291–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalingam, A.; Geonnotti, A.R.; Balzarini, J.; Kiser, P.F. Activity and safety of synthetic lectins based on benzoboroxole-functionalized polymers for inhibition of HIV entry. Mol. Pharm. 2011, 8, 2465–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narla, S.N.; Pinnamaneni, P.; Nie, H.; Li, Y.; Sun, X. BSA-boronic acid conjugate as lectin mimetics. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 443, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, S.; Davidson, M.G.; van den Elsen, J.H.; Fossey, J.S.; Jenkins, A.T.A.; Jiang, Y.; Kubo, Y.; Marken, F.; Sakurai, K.; Zhao, J.; et al. Exploiting the reversible covalent bonding of boronic acids: Recognition, sensing, and assembly. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watahiki, R.; Sato, K.; Suwa, K.; Niina, S.; Egawa, Y.; Seki, T.; Anzai, J. Multilayer films composed of phenylboronic acid-modified dendrimers sensitive to glucose under physiological conditions. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 5809–5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Takahashi, M.; Ito, M.; Abe, E.; Anzai, J. H2O2-induced decomposition of layer-by-layer films consisting of phenylboronic acid-bearing poly(allylamine) and poly(vinyl alcohol). Langmuir 2014, 30, 9247–9250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Bie, Z.; Lü, C.; Liu, Z. Magnetic nanoparticles with dendrimer-assisted boronate avidity for the selective enrichment of trace glycoproteins. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 4298–4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, H.; Chen, B.; Mendes, P.M.; Fossey, J.S.; James, T.D.; Long, Y. A bis-boronic acid modified electrode for the sensitive and selective determination of glucose concentrations. Analyst 2013, 138, 7146–7151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwa, K.; Nagasaka, M.; Niina, S.; Egawa, Y.; Seki, T.; Anzai, J. Sugar response of layer-by-layer films composed of poly(vinyl alcohol) and poly(amidoamine) dendrimer bearing 4-carboxyphenylboronic acid. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2015, 293, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, M.; Otsuki, A.; Nishihara, M.; Okamoto, R.; Kajihara, Y. Chemical synthesis of a synthetic analogue of the sialic acid-binding lectin siglec-7. ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 2503–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Anzai, J. Recent progress in electrochemical HbA1c sensors: A review. Materials 2015, 8, 1187–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Takahashi, M.; Ito, M.; Abe, E.; Anzai, J. Glucose-induced decomposition of layer-by-layer films composed of phenylboronic acid-bearing poly(allylamine) and poly(vinyl alcohol) under physiological conditions. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 7796–7802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Lin, H.; Ge, S.; Luo, S.; Cai, Q.; Grimes, C.A. Wireless, remote-query, and high sensitivity Echerichia coli O157:H7 biosensor based on the recognition action of cocanavalin A. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 5846–5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Lu, Q.; Ge, S.; Cai, Q.; Grimes, C.A. Detection of pathogen Echerichia coli O157:H7 with a wireless magnetoelastic-sensing device amplified by using chitosan-modified magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Sens. Actuators B 2010, 147, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.; Liu, S.; Zeng, W.; Zou, H.; Wang, L.; Suresh, V.; Beuerman, R.; Cao, D. Electron donating group substituted and α-d-mannopyranoside directly functionalized polydiacetylene as a simplified bio-sensing system for detection of lectin and E. coli. Sens. Actuators B 2013, 178, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhou, L.; He, D.; Wang, K.; Cao, J. Rapid and ultrasensitive, E. coli O157:H7 quantitation by combination of ligandmagnetic nanoparticles enrichment with fluorescent nanoparticles based two-color flow cytometry. Analyst 2011, 136, 4183–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Lei, Z.; Liu, F.; Liu, D.; Wang, Z. Fabricating three-dimensional carbohydrate hydrogel microarray for lectin-mediated bacterium capturing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 58, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, J.S.L.; Oliveira, M.D.L.; de Melo, C.P.; Andrade, C.A.S. Impedimetric sensor of bacteria toxins based on mixed (concanavalin A)/polyaniline films. Colloid Surf. B 2014, 117, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, F.; Rehman, A.; Sims, M.; Zeng, X. Antimicrobial susceptibility assay based on the quantification of bacterial lipopolysaccharides via a label free lectin biosensors. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 4385–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandenius, C.; Wang, R.; Aldén, A.; Bergström, G.; Thebault, S.; Lutsch, C.; Ohlson, S. Monitoring of influenza virus hemagglutinin in process samples using weak affinity ligands and surface plasmon resonance. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 623, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Jin, S.I.; Kim, H.M.; Ahn, J.; Kim, Y.; Lee, E.G.; Kim, M.; Shin, Y. Monitoring change in refractive index of cytosol of animal cells on affinity surface under osmotic stimulus for label-free measurement of viability. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 64, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, P.; Zhang, D.; Wan, Y.; Lv, D. A facile approach to construct versatile signal amplification system for bacteria detection. Talanta 2014, 118, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Anzai, J. Recent progress in ferrocene-modified thin films and nanoparticles for biosensors. Materials 2013, 6, 5742–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.D.L.; Correia, M.T.S.; Diniz, F.B. A novel approach to classify serum glycoproteins from patients infected by dengue using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy analysis. Synth. Met. 2009, 159, 2162–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, K.Y.P.S.; Andrade, C.A.S.; de Melo, C.P.; Nogueira, M.L.; Correia, M.T.S.; Coelho, L.C.B.B.; Oliveira, M.D.L. Biosensor based on hybrid nanocomposite and CramoLL lectin for detection of dengue glycoproteins in real samples. Synth. Met. 2014, 194, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, D.M.; Oliveira, M.D.L.; Nogueria, M.L.; Andrade, C.A.S. Biosensor based on lectin and membranes for detection of serum glycoproteins in infected patients with dengue. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2014, 180, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

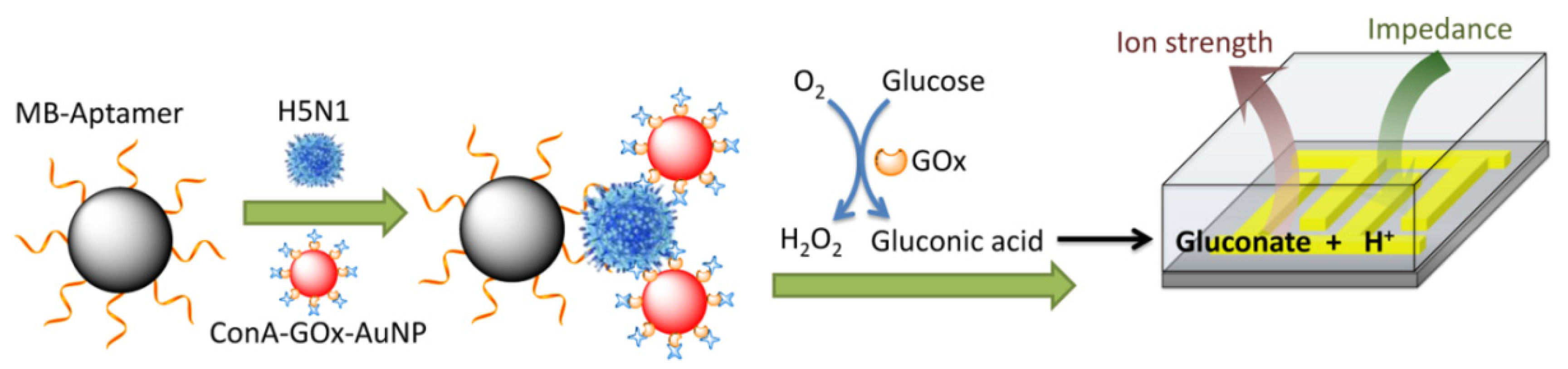

- Fu, Y.; Callaway, Z.; Lum, J.; Wang, R.; Lin, J.; Li, Y. Exploiting enzyme catalysis in ultra-low ion media for impedance biosensing of avian influenza virus using a bare interdigitated electrode. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 1965–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Gu, B. A displacement assay for the sensing of carbohydrate using zinc oxide biotracers. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 60, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandy, B.; Bhattarai, J.K.; Pornsuriyasak, P.; Fijikawa, K.; Catania, R.; Demchenko, A.V.; Stine, K.J. Square-wave voltammetry assays for glycoproteins on nanoporous gold. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2014, 717–718, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Li, D.; Xi, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, E. Three-dimensional electrochemical immunosensor for sensitive detection of carcinoembryonic antigen based on monolithic and macroporous graphene foam. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 65, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, K.; Fukase, Y.; Katagiri, T.; Ishikawa, N.; Irie, S.; Sato, T.; Ito, H.; Nakayama, H.; Miyagi, Y.; Tsuchiya, E.; et al. Targeted serum glycoproteomics for the discovery of lung cancer-associated glycosylation disorders using lectin-coupled protein chip assays. Proteomics 2009, 9, 2182–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, C.; Qian, S.; Wang, Z.; Qu, B. Electrochemical cytosensor based on gold nanoparticles for the determination of carbohydrate on cell surface. Anal. Biochem. 2011, 414, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zuo, P.; Ye, B. Label-free electrochemical impedance spectroscopy biosensor for direct detection of cancer cells based on the interaction between carbohydrate and lectin. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 43, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancino-Bernardi, J.; Marangoni, V.S.; Faria, H.A.M.; Zocolotto, V. Detection of leukemic cells by using jacalin as the biorecognition layer: A new strategy for the detection of circulating tumor cells. ChemElectroChem 2015, 2, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Saint-Guirons, J.; Käck, C.; Ingemarsson, B.; Aastrup, T. Real-time analysis of the carbohydrates on cell surfaces using a QCM biosensor: A lectin-based approach. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 35, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

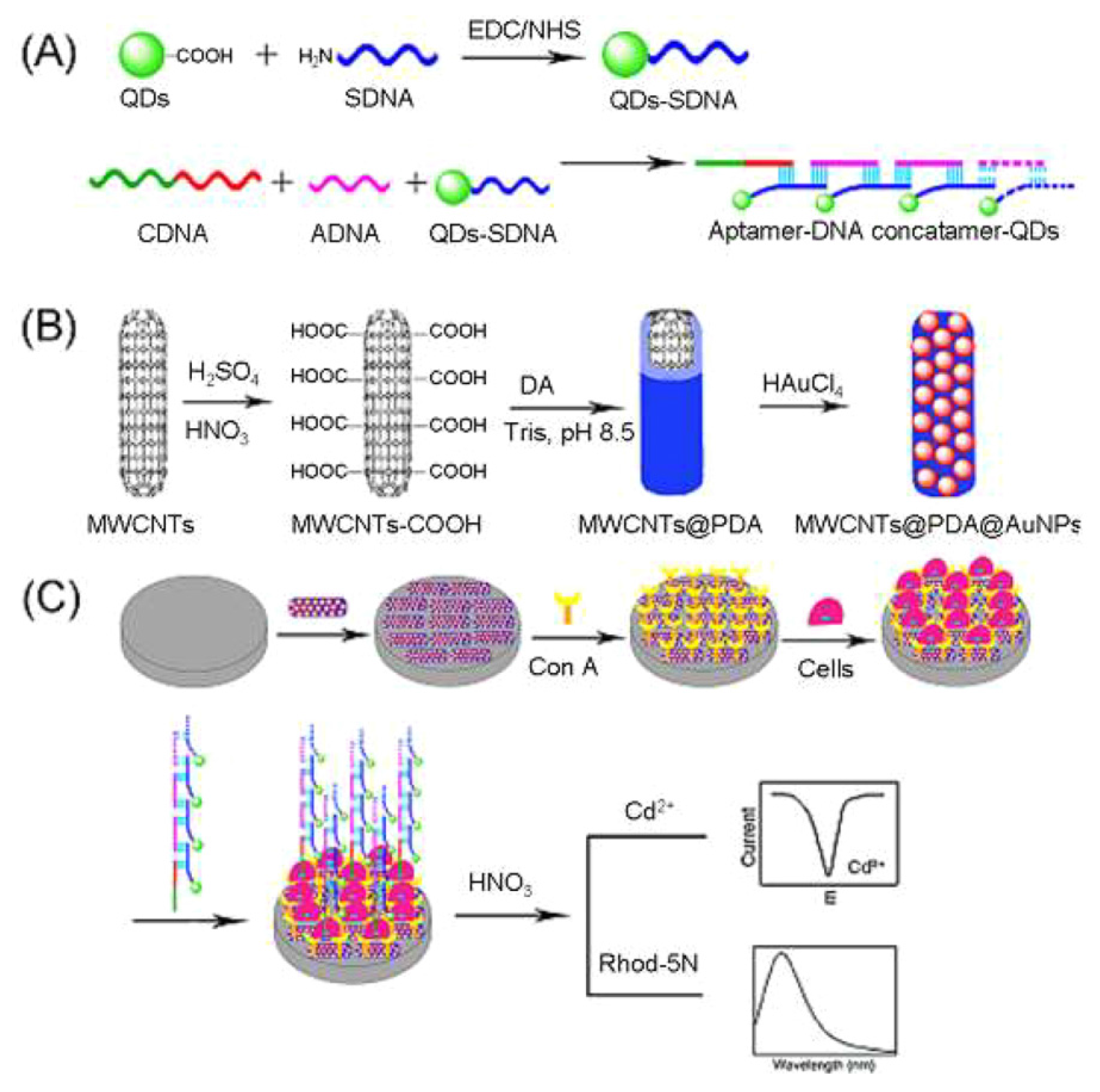

- Liu, H.; Xu, S.; He, Z.; Deng, A.; Zhu, J. Supersandwich cytosensor for selective and ultrasensitive detection of cancer cells using aptamer-DNA concatamer-quantum dots probes. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 3385–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Teng, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, T.; Wang, C.; Jin, L.; Zhang, W. Lectin-based electrochemical biosensor constructed by functionalized carbon nanotubes for the competitive assay of glycan expression on living cancer cells. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 2353–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Lu, D.; Lin, B.; Sun, Q.; Liu, K.; Xu, L.; Zhang, S.; Hu, C.; Wang, C.; Xu, Z.; et al. Fluorescence assay for glycan expression on living cancer cells based on competitive strategy coupled with dual-functionalized nanobiocomposites. Analyst 2013, 138, 7016–7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, J. Dynamic evaluation of cell surface N-glycan expression via an electrogenerated chemiluminescence biosensor based on concanavalin A-integrating gold-nanoparticle-modified Ru(bpy)32+-doped silica nanoprobe. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 4431–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, J. Sensitive electrochemical aptamer biosensors for dynamic cell surface N-glycan evaluation featuring multivalent recognition and signal amplification on a dendrimer-graphene electrode interface. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 4278–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Yang, D.; Ye, D.; Zhang, X.; Fang, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, B.; Kong, J. Protein-inorganic hybrid nanoflowers as ultrasensitive electrochemical cytosensing interfaces for evaluation of cell surface sialic acid. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 68, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, J. A functional glycoprotein competitive recognition and signal amplification strategy for carbohydrate-protein interaction profiling and cell surface carbohydrate expression evaluation. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 7349–7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

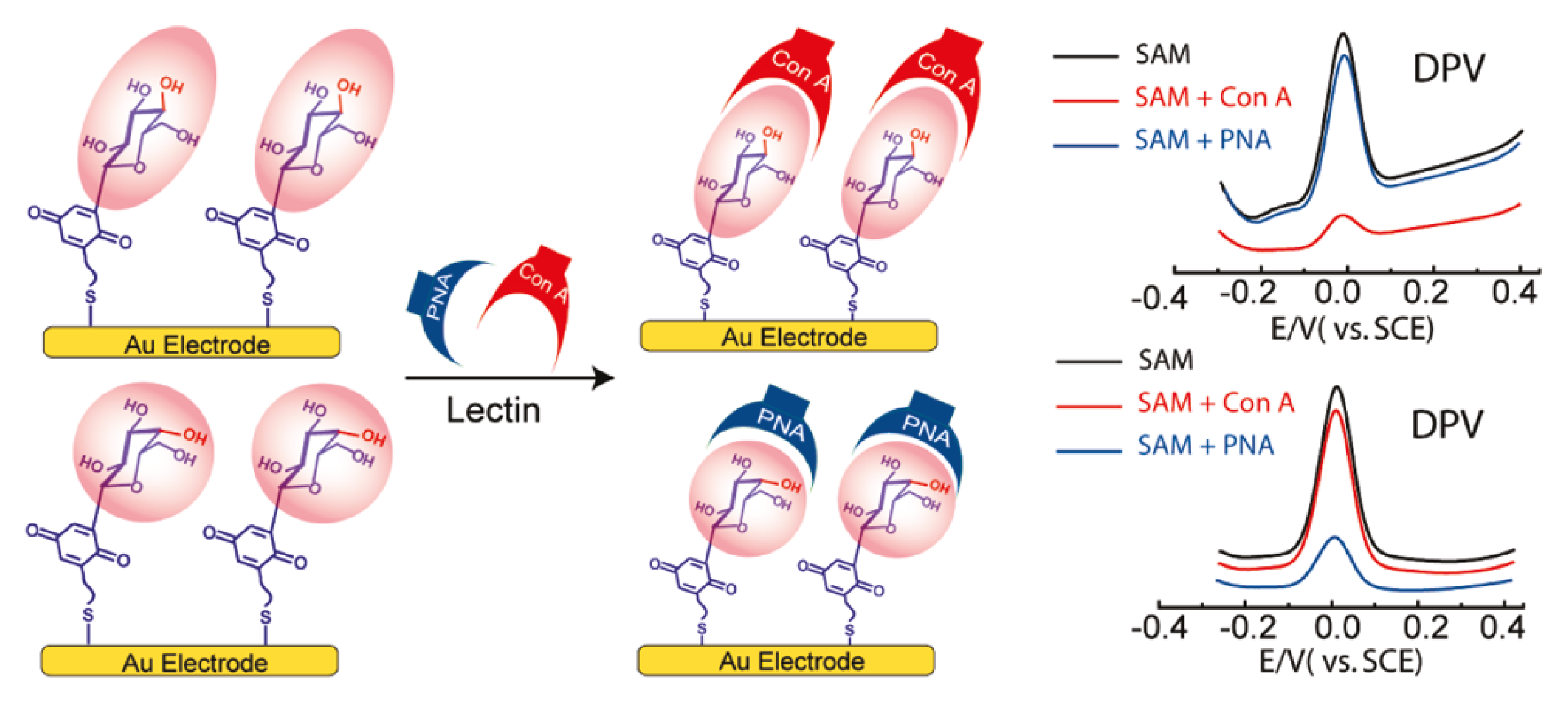

- He, X.; Wang, X.; Jn, X.; Zhou, H.; Shi, X.; Chen, G.; Long, Y. Epimeric monosaccharide-quinone hybrids on gold electrodes toward the electrochemical probing of specific carbohydrate-protein recognitions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 3649–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Yu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zeng, X. Complex thiolated mannose/quinone film modified on EQCM/Au electrode for recognizing specific carbohydrate-proteins. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 55, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, I.; Choi, L.; Ahn, K.; Kim, B.K.; Lee, B.Y.; Kim, K.S.; Choi, H.N.; Lee, W. Electrochemical determination of carbohydrate-binding proteins using carbohydrate-stabilized gold nanoparticles and silver enhancement. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 1326–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loaiza, O.A.; Lamas-Ardisana, P.J.; Jubete, E.; Ochoteco, E.; Loinaz, I.; Cabañero, G.; García, I.; Penadés, S. Nanostructured disposable impedimetric sensors as tools for specific biomolecular interactions: Sensitive recognition of concanavalin A. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 2987–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.; Chen, S.; Wang, C.; Yuan, R.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, C. Multi-wall carbon nanotube-polyaniline biosensor based on lectin-carbohydrate affinity for ultrasensitive detection of Con A. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 34, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, C.; Vegesna, G.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Zeng, X. Glycosylated aniline polymer sensor: Amine to imine conversion on protein-carbohydrate binding. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 46, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Boullanger, P.; Jiang, L.; Liu, T. One-step immobilization of alkanethiol/glycolipid vesicles onto gold electrode: Amperometric detection of concanavalin, A. Colloid Surf. B 2008, 62, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, K.; Kadoya, T.; Kuramiz, H. Electrochemical sensing of concanavalin A using a non-ionic surfactant with a maltose moiety. Anal. Chim. Acta 2014, 814, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ruo, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhong, X.; Wu, X. A sandwich-like electrochemiluminescent biosensor for the detection of concanavalin a based on a C60-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite and glucose oxidase functionalized hollow gold nanosheres. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 48465–48471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Ruo, Y.; Zhong, X.; Wu, X. An ultrasensitive electrochemiluminescent biosensor for the detection of concanavalin A based on poly(ethylenimine) reduced graphene oxide and hollow gold nanoparticles. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, X.; Tan, X.; Liu, X.; Lu, Q.; Chen, S.; Wei, S. A signal-on electrochemiluminescence biosensor for detecting Con A using phenoxy dextran-graphene-like carbon nitride as signal probe. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 70, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Cai, L.; Pu, K.; Liu, B. Synthesis and characterization of water-soluble conjugated glycopolymer for fluorescent sensing of concanavalin A. Chem. Asian J. 2010, 5, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, K.R.; Ahn, K.; Lee, W. Detection of concanavalin A based on attenuated fluorescence resonance energy transfer between quantum dots and mannose-stabilized gold nanoparticles. Anal. Methods 2013, 5, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Anzai, J.-i. Recent Progress in Lectin-Based Biosensors. Materials 2015, 8, 8590-8607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma8125478

Wang B, Anzai J-i. Recent Progress in Lectin-Based Biosensors. Materials. 2015; 8(12):8590-8607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma8125478

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Baozhen, and Jun-ichi Anzai. 2015. "Recent Progress in Lectin-Based Biosensors" Materials 8, no. 12: 8590-8607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma8125478

APA StyleWang, B., & Anzai, J.-i. (2015). Recent Progress in Lectin-Based Biosensors. Materials, 8(12), 8590-8607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma8125478