Bifaciality Optimization of TBC Silicon Solar Cells Based on Quokka3 Simulation

Highlights

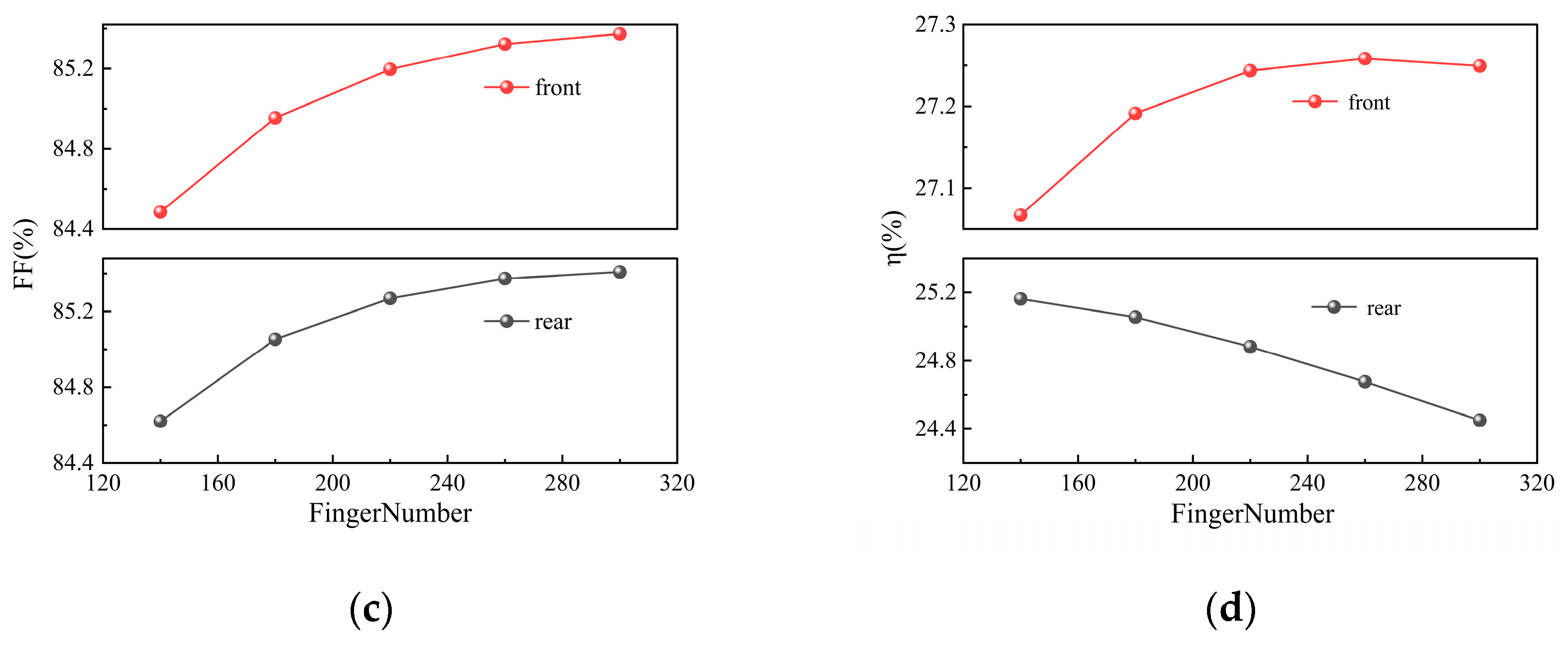

- A simulated conversion efficiency of 27.26% and a bifaciality ratio of 92.96% have been achieved for TBC solar cells.

- By considering the interaction between parameters, the optimal performance balance point was determined.

- An integrated opto-electrical analysis and design were specifically conducted.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cell Structure and Simulation Methodology

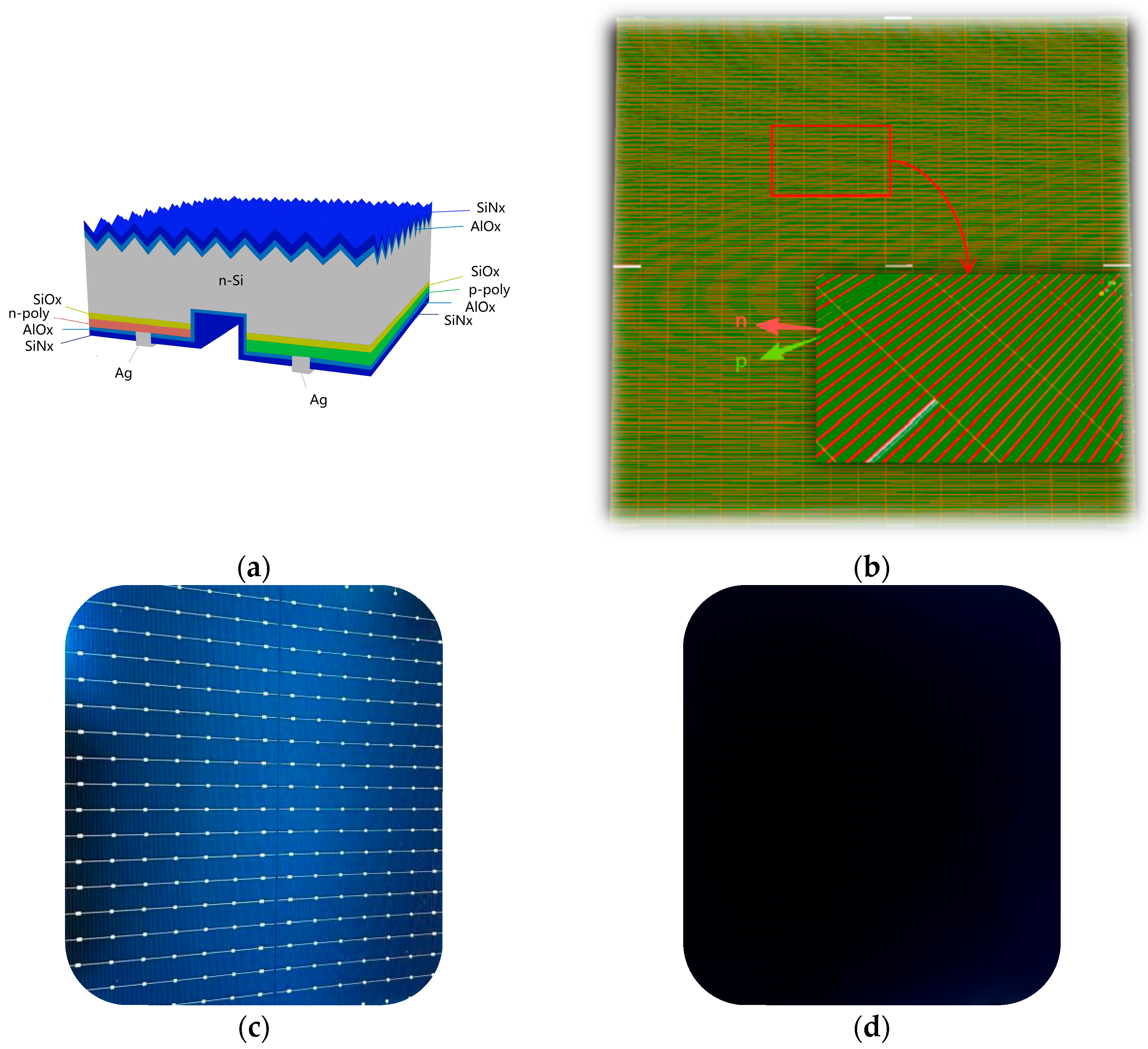

2.1. Cell Structure

2.2. Simulation Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

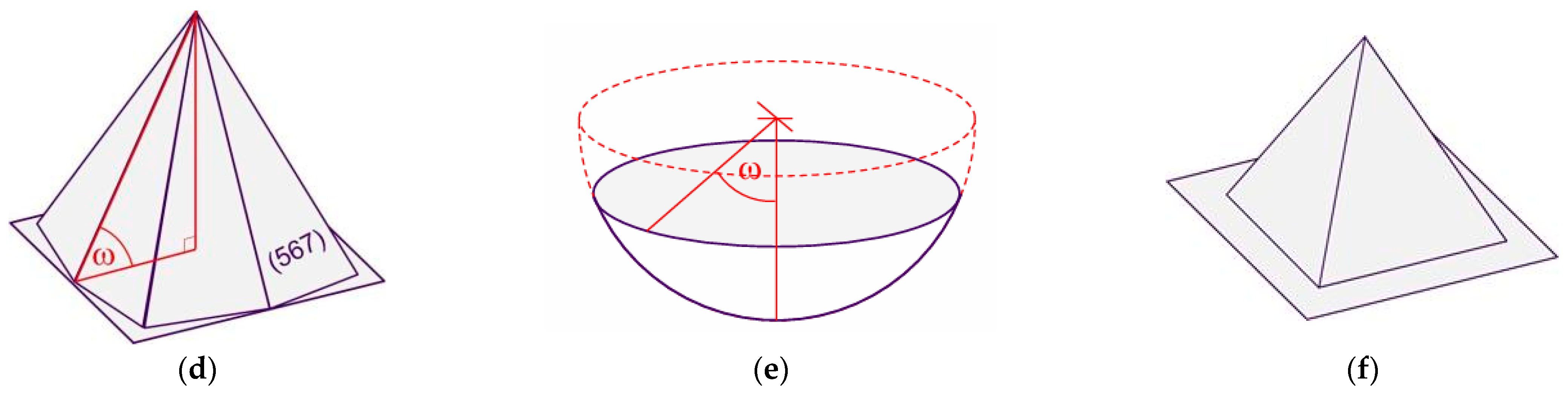

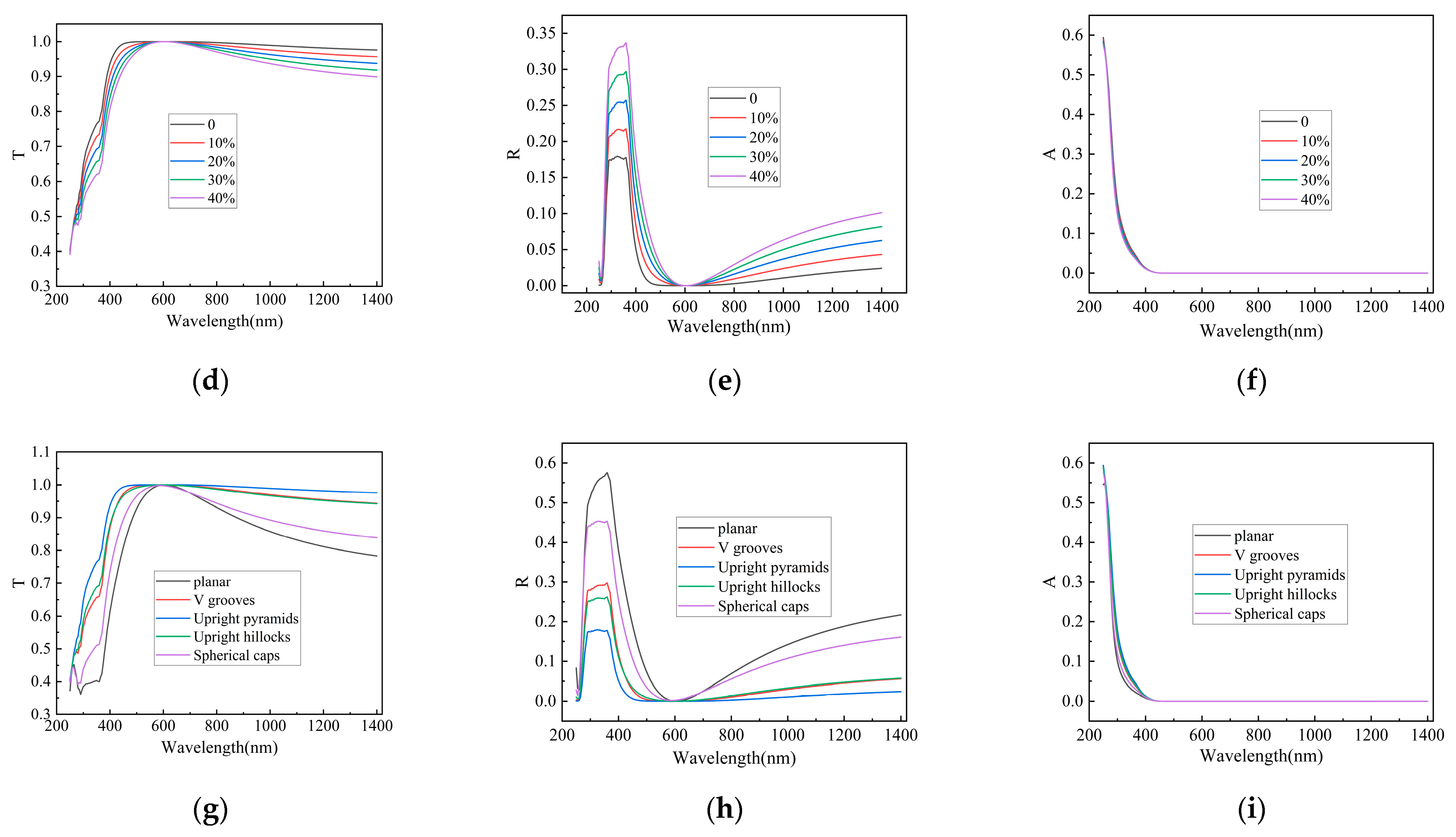

3.1. Optical Film Stack Structure

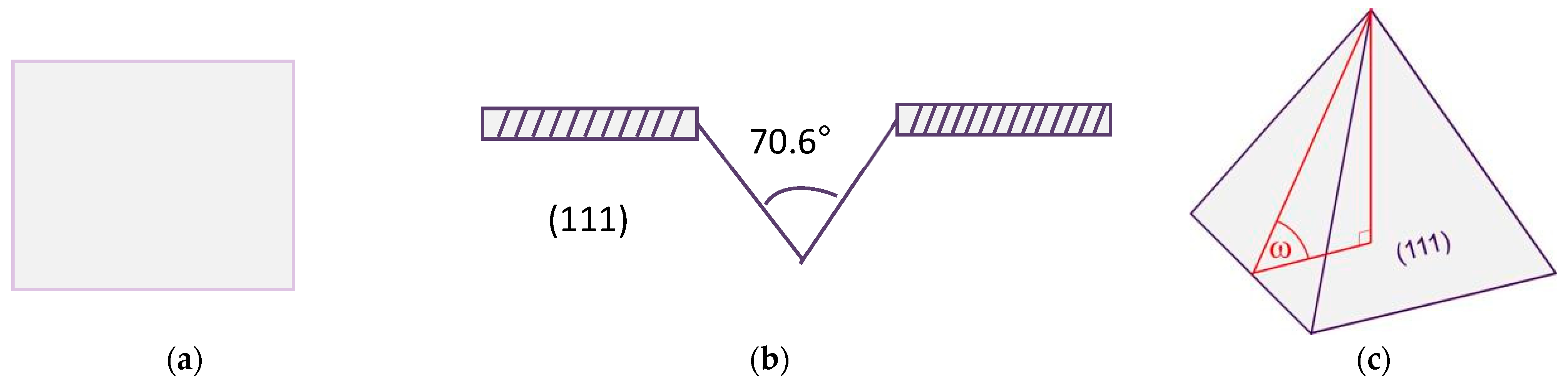

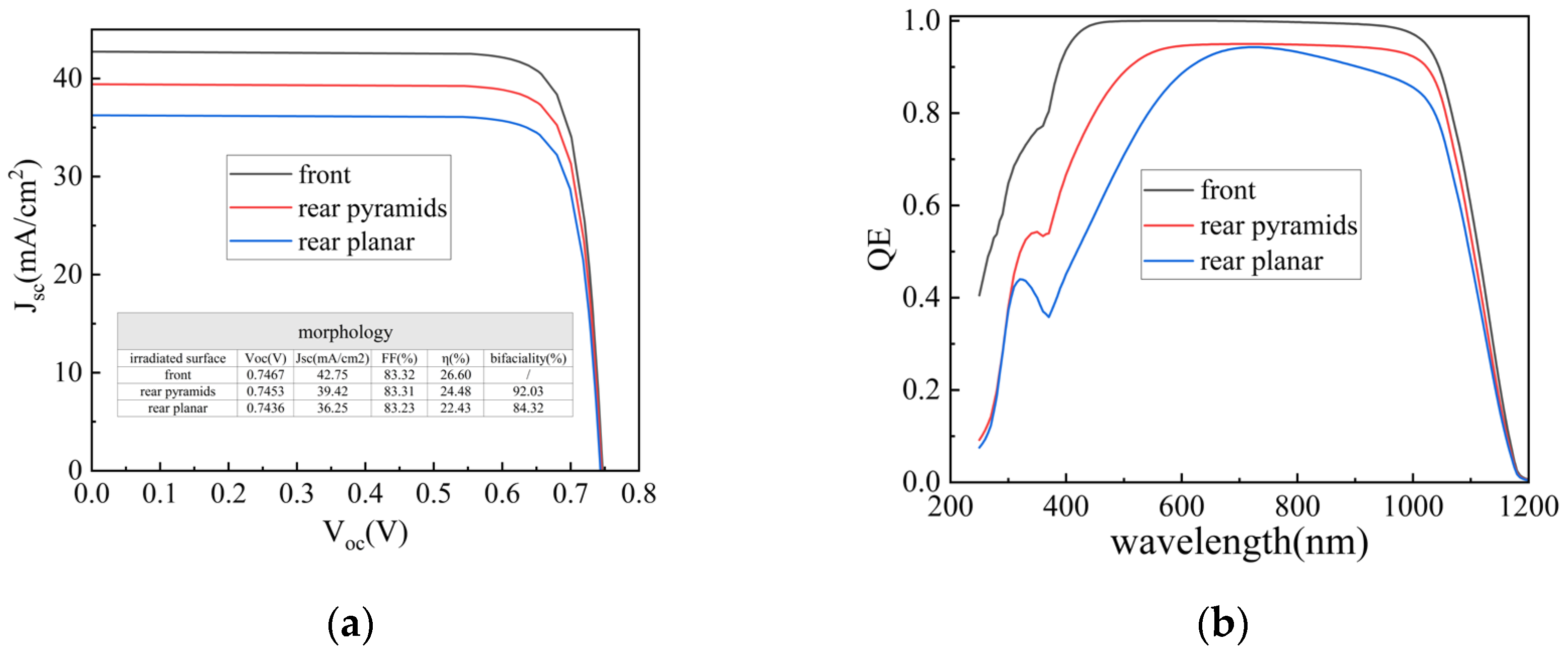

3.2. Different Rear-Side Morphologies

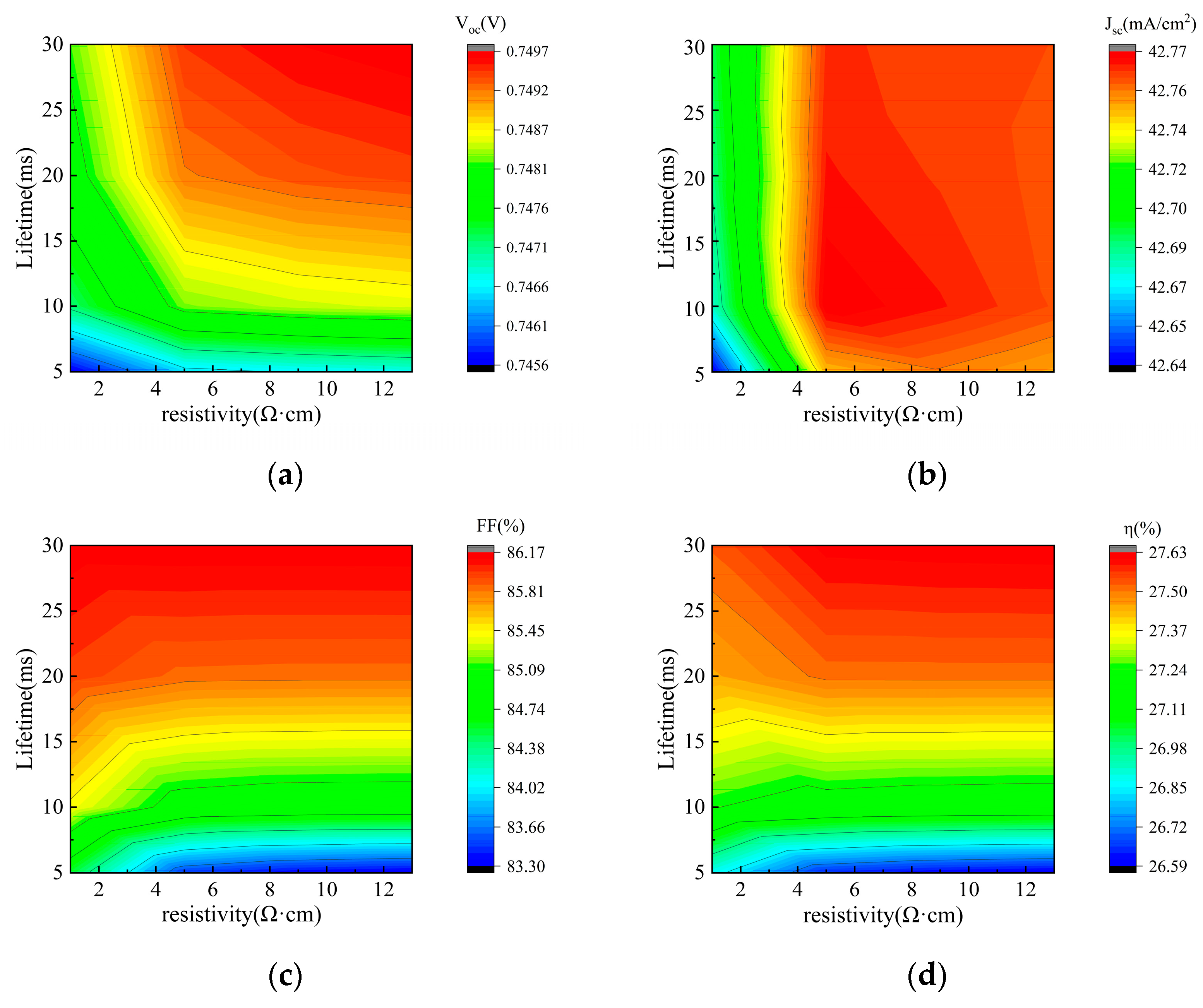

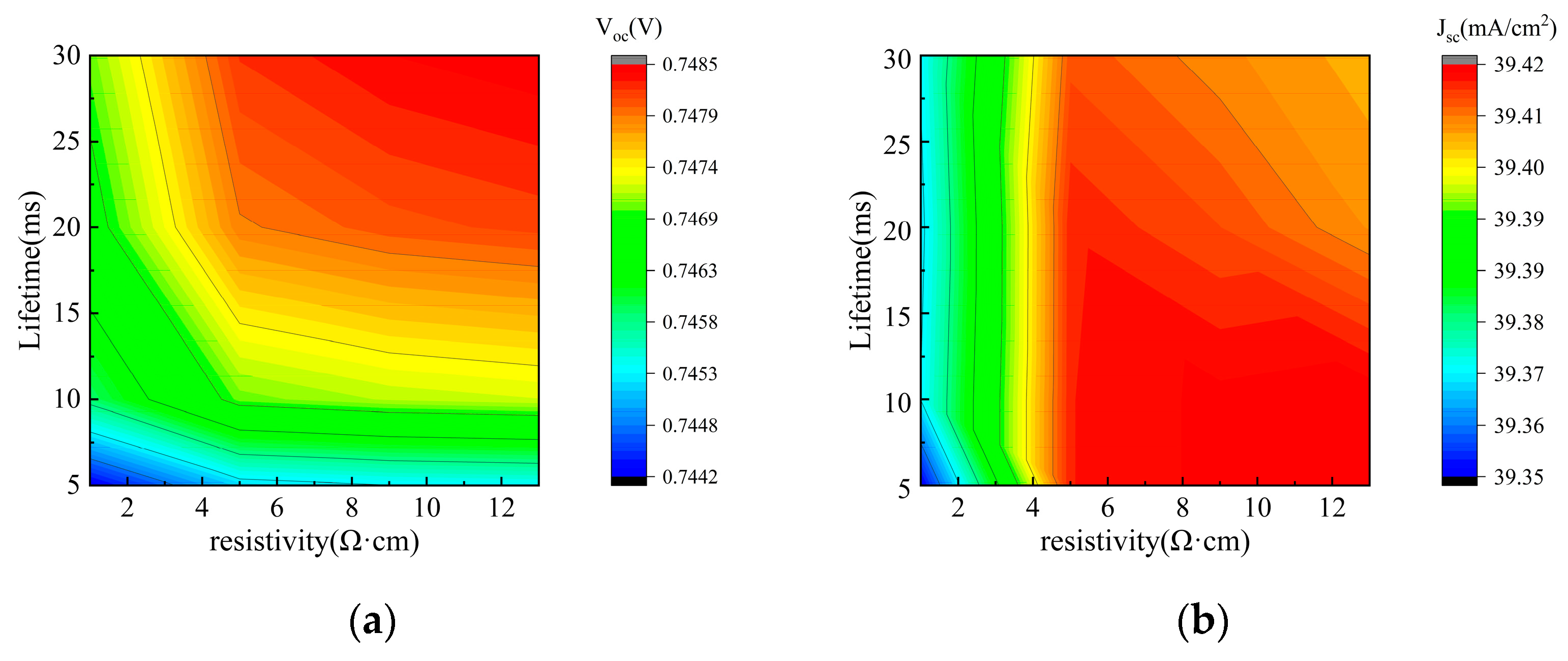

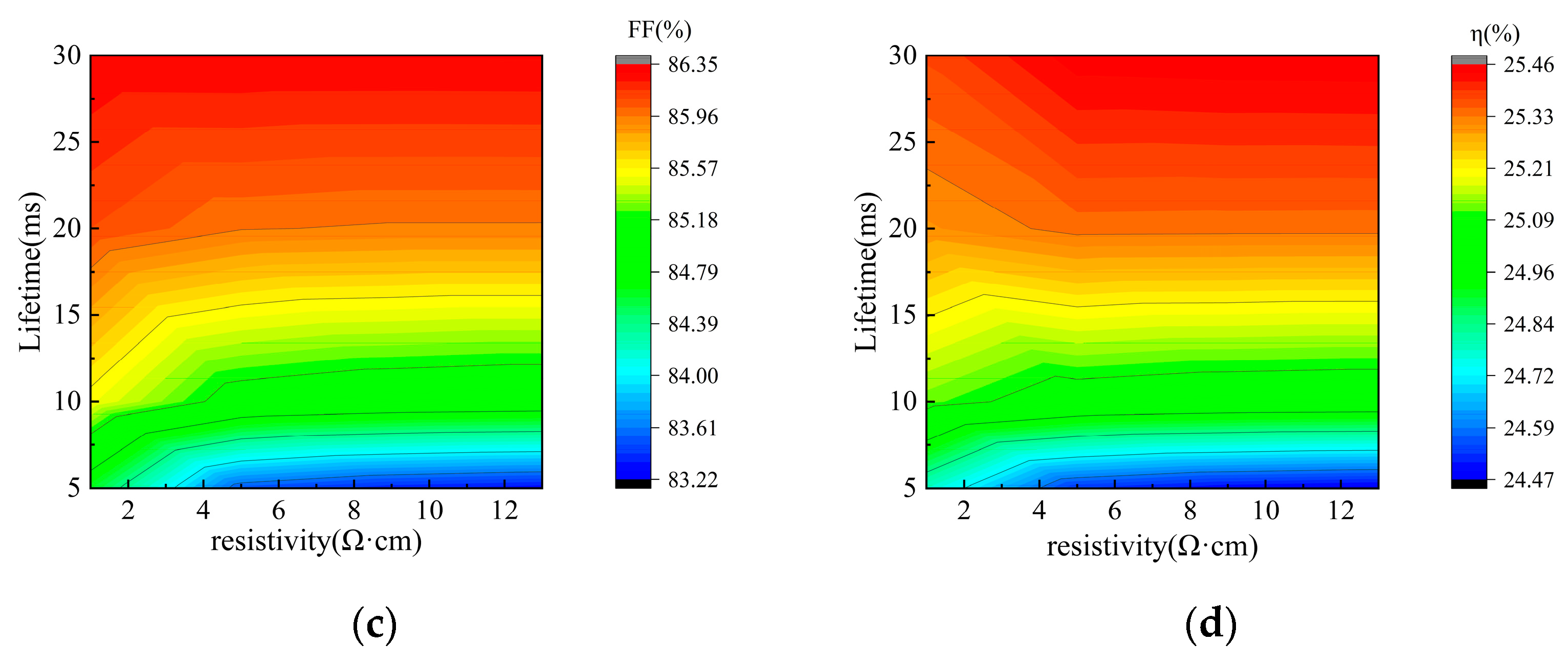

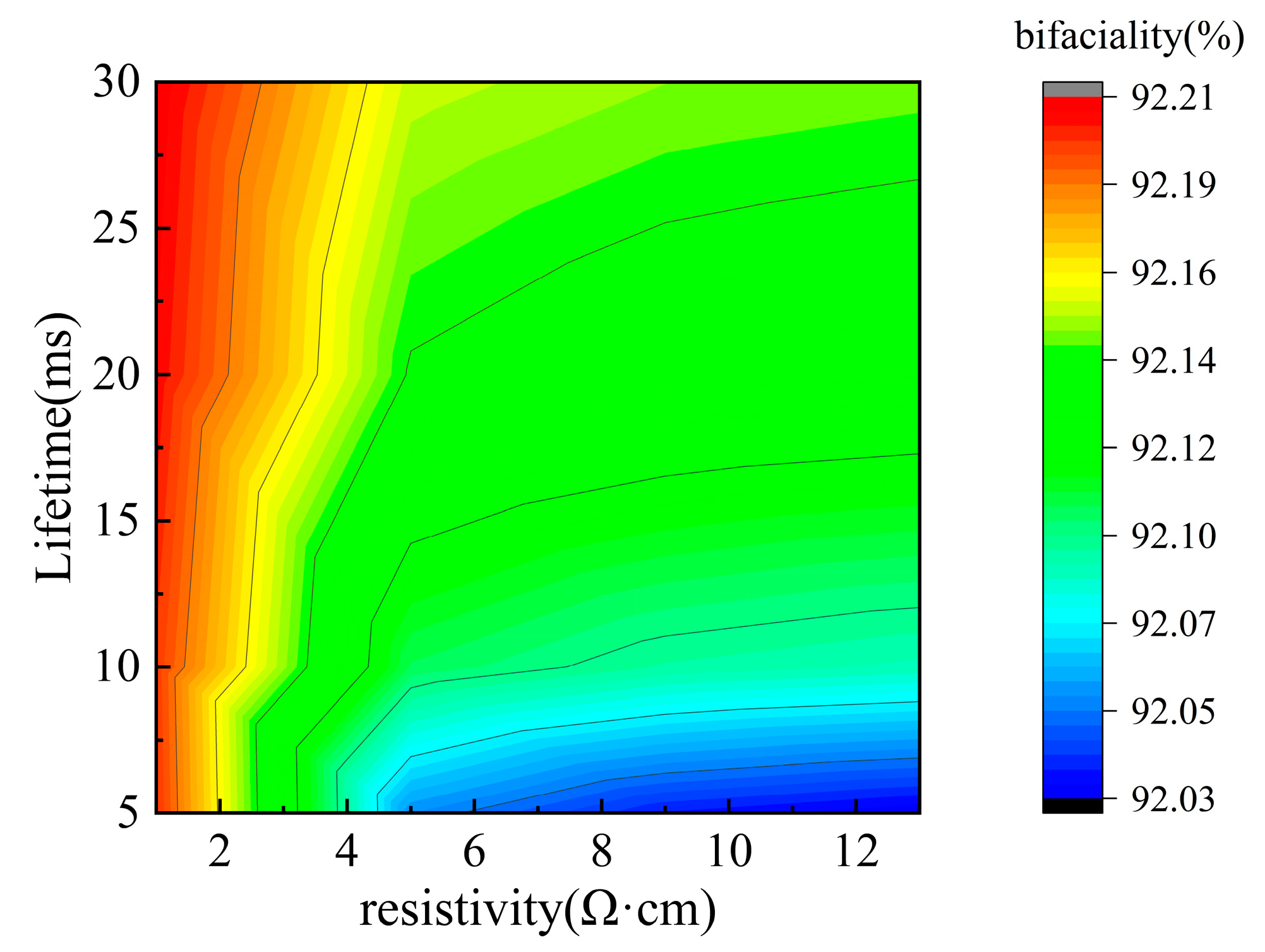

3.3. Bulk Resistivity and Minority-Carrier Lifetime

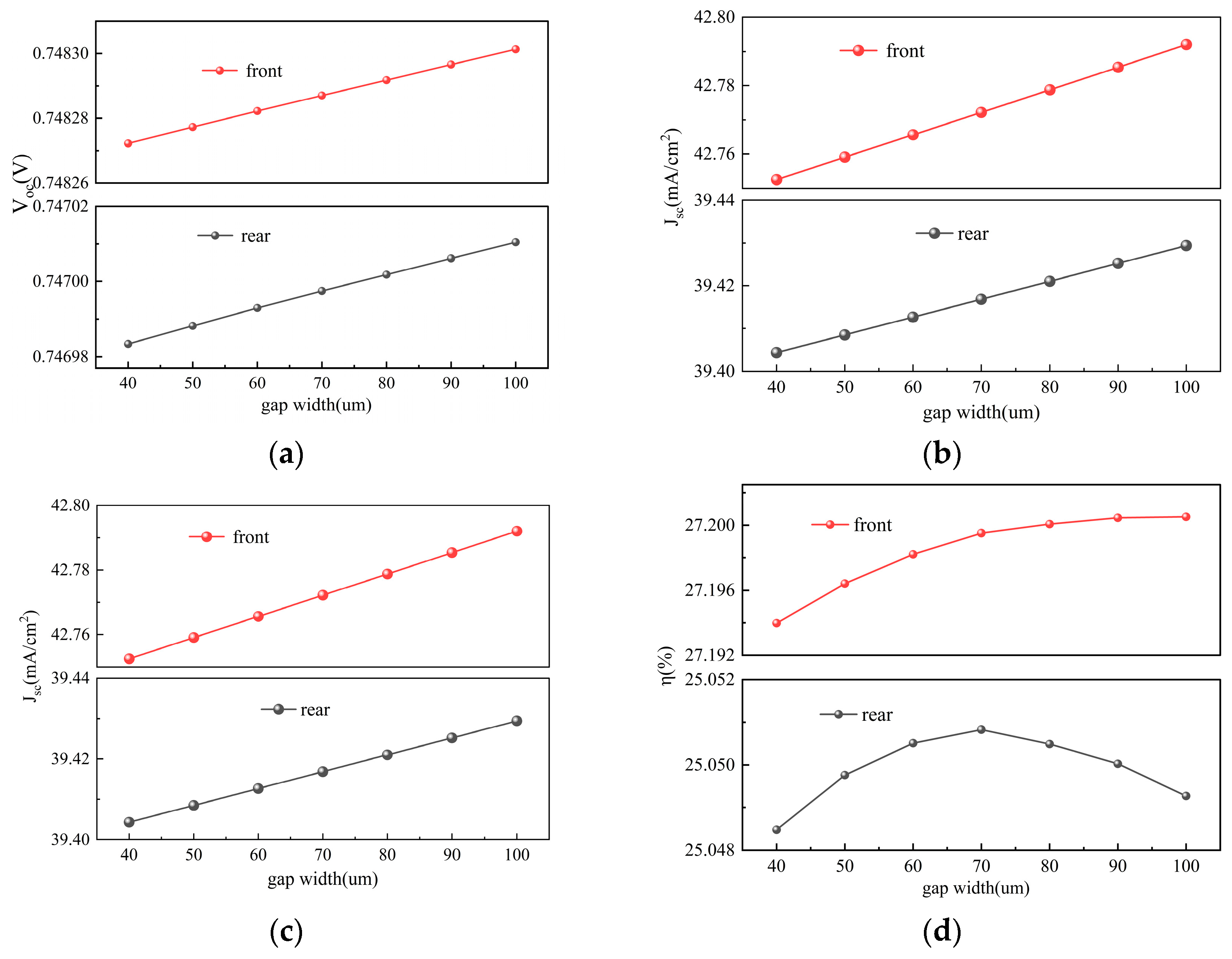

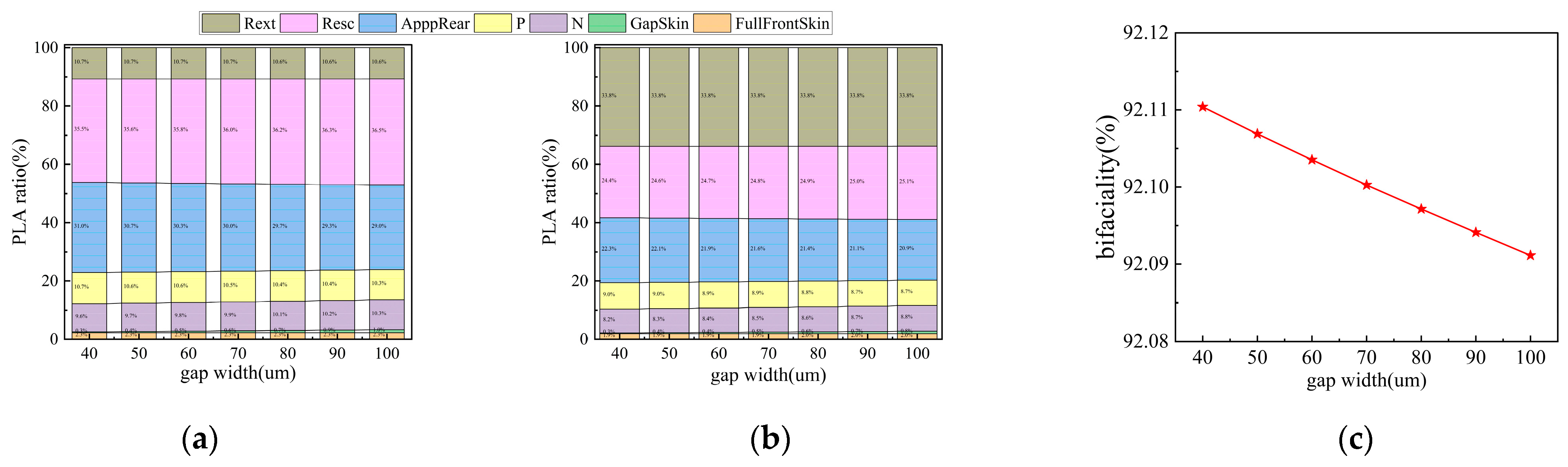

3.4. Gap Region Width

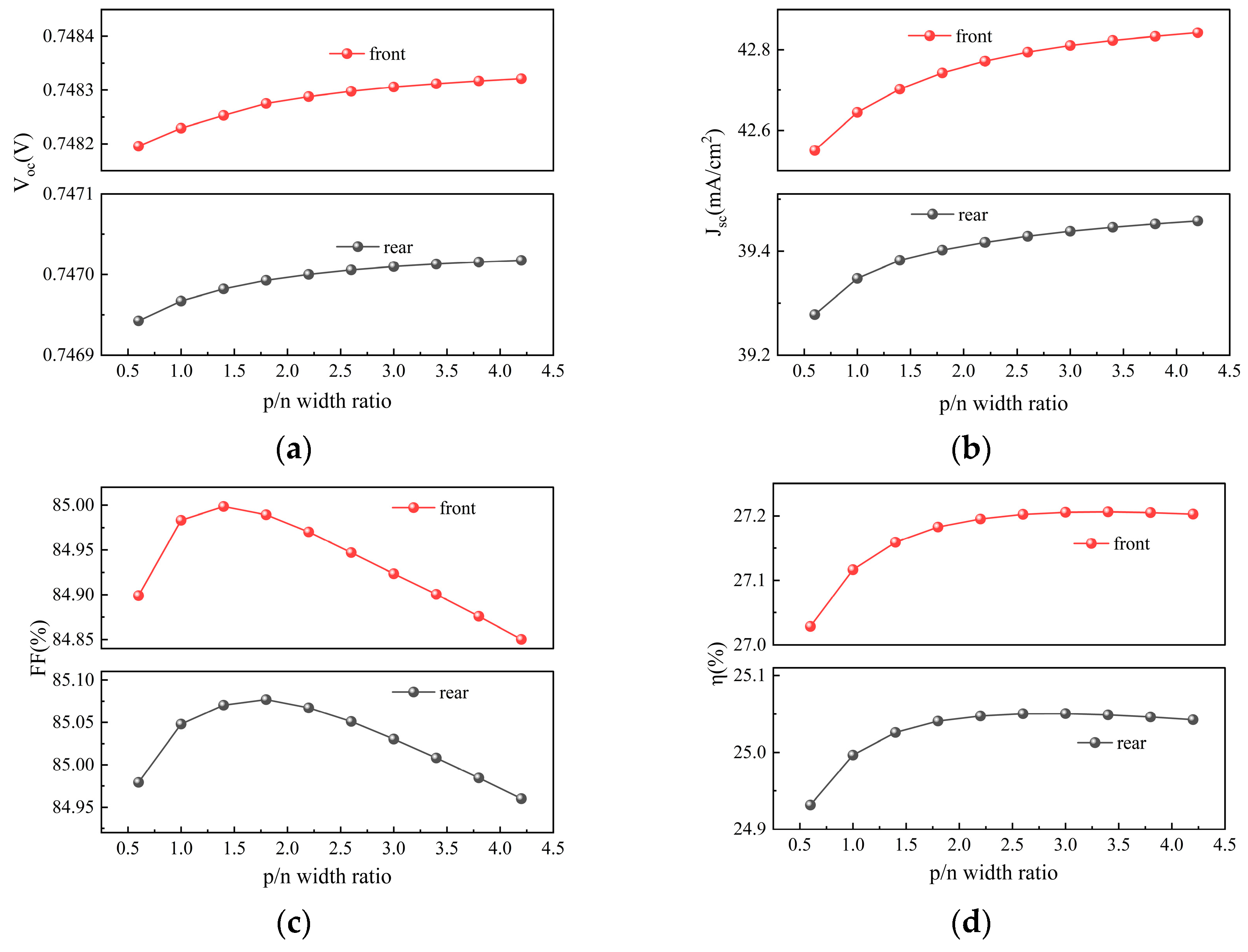

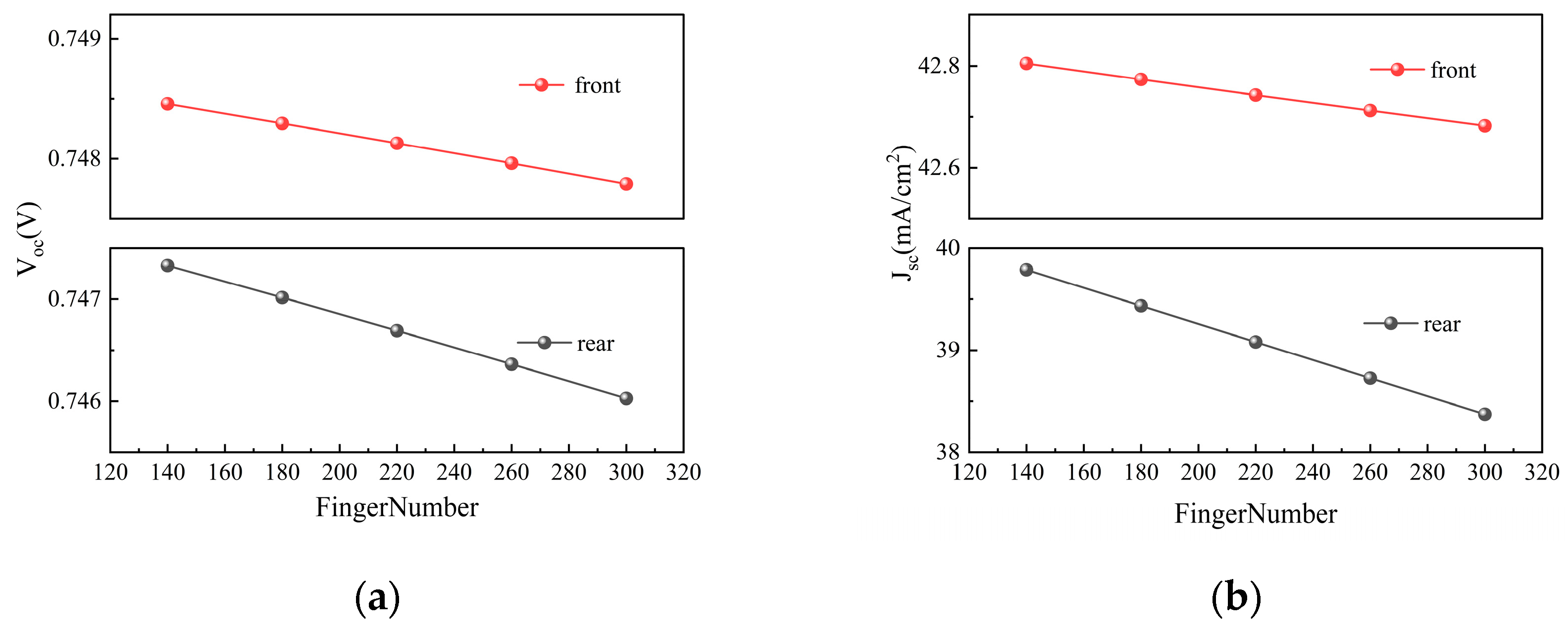

3.5. Emitter Ratio and Finger Pitch

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joseph, K.L.V.; Rosana, N.T.M.; Kumar, J.A.; Samrot, A.V. Commercial bifacial silicon solar cells—Characteristics, module topology and passivation techniques for high electrical output: An overview. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Influence of module types on theoretical efficiency and aesthetics of colored photovoltaic modules with luminescent down-shifting layers. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 279, 113254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Ingenito, A.; Isabella, O.; Zeman, M. IBC c-Si solar cells based on ion-implanted poly-silicon passivating contacts. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 158, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiri, H.; Karami, M.A.; Mohammadnejad, S. A new interdigitated back contact silicon solar cell with higher efficiency and lower sensitivity to the heterojunction defect states. Superlattices Microstruct. 2018, 120, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desa, M.M.; Sapeai, S.; Azhari, A.; Sopian, K.; Sulaiman, M.; Amin, N.; Zaidi, S. Silicon back contact solar cell configuration: A pathway towards higher efficiency. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 1516–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Asadpour, R.; Alam, M.A.; Bermel, P. Tailoring interdigitated back contacts for high-performance bifacial silicon solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 114, 103901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuku, S.A.; Bennadji, A.; Muhammad-Sukki, F.; Sellami, N. Myth or gold? The power of aesthetics in the adoption of building integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs). Energy Nexus 2021, 4, 10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukortt, N.E.I.; Patanè, S.; Bouhjar, F. Design, Optimization and Characterisation of IBC c-Si (n) Solar Cell. Silicon 2019, 12, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, N.C.; Biswas, S.; Acharya, S.; Panda, T.; Sadhukhan, S.; Sharma, J.R.; Nandi, A.; Bose, S.; Kole, A.; Das, G.; et al. Study of the properties of SiOx layers prepared by different techniques for rear side passivation in TOPCon solar cells. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2020, 119, 105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, W.; Yuan, N.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, J. Influence of SiOx film thickness on electrical performance and efficiency of TOPCon solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 208, 110423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Kang, Q.; Sun, Z.; He, Y.; Li, J.; Sun, C.; Xue, C.; Qu, M.; Chen, X.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Optimizing strategy of bifacial TOPCon solar cells with front-side local passivation contact realized by numerical simulation. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 278, 113189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yu, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, P.; Ke, Y.; Liu, W.; Wan, Y.W. Influence of rear surface pyramid base microstructure on industrial n-TOPCon solar cell performances. Sol. Energy 2022, 247, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Gao, C.; Wang, X.; Du, D.; Ma, S.; Li, Z.; Shen, W.D. Optimization of rear surface morphology in n-type TOPCon c-Si solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 277, 113142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Yang, Z.; Wang, M.; Liang, Y.; Liu, J.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, L.; Cao, G.; Li, X.; et al. Physical mechanisms and design strategies for high-efficiency back contact tunnel oxide passivating contact solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 289, 113656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yan, L.; Chen, Z.; Liu, S.; Yao, Z.; Chen, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Huang, Y.; et al. Rapid phosphorus diffusion on the poly-silicon surface of tunnel back contact solar cells via silicon paste. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 085957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Yang, Z.; Feldmann, F.; Polzin, J.-I.; Steinhauser, B.; Phang, S.P.; Macdonald, D. Understanding the impurity gettering effect of polysilicon/oxide passivating contact structures through experiment and simulation. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2021, 230, 111254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peibst, R.; Haase, F.; Min, B.; Hollemann, C.; Brendemühl, T.; Bothe, K.; Brendel, R. On the chances and challenges of combining electron-collecting nPOLO and hole-collecting Al-p+ contacts in highly efficient p-type c-Si solar cells. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2022, 31, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yu, B.; He, Y.; Lv, A.; Fan, J.; Yang, L.; Xia, Z.; Li, Z.; Meng, X.; Jiang, F.; et al. Enabling 95% bifaciality of efficient TOPCon solar cells by rear-side selective sunken pyramid structure and zebra-crossing passivation contact. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 292, 113809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Wang, G.; Sun, Y.; Cai, H.; Su, X.; Cao, P.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; He, J.; Gao, P. Bifacial silicon heterojunction solar cells using transparent-conductive-oxide- and dopant-free electron-selective contacts. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2024, 32, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmüller, E.; Werner, S.L.N.; Norouzi, M.H.; Saint-Cast, P.; Weber, J.; Meier, S.; Wolf, A. Towards 90% bifaciality for p-type Cz-Si solar cells by adaption of industrial PERC processes. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 7th World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conversion (WCPEC) (A Joint Conference of 45th IEEE PVSC, 28th PVSEC & 34th EU PVSEC), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 10–15 June 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, H.; Tan, S.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y.; Ding, C.; Zhang, H.; He, J.; Cao, J.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Total-area world-record efficiency of 27.03% for 350.0 cm2 commercial-sized single-junction silicon solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ye, F.; Yang, M.; Luo, F.; Tang, X.; Tang, Q.; Qiu, H.; Huang, Z.; Wang, G.; Sun, Z.; et al. Silicon heterojunction back-contact solar cells by laser patterning. Nature 2024, 635, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, K.R.; Baker-Finch, S.C. OPAL 2: Rapid optical simulation of silicon solar cells. In Proceedings of the 38th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 3–8 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Finch, S.C.; McIntosh, K.R. A freeware program for precise optical analysis of the front surface of a solar cell. In Proceedings of the 35th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 20–25 June 2010; pp. 2184–2187. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, H.; Bhattacharya, S.; Alam, S.; Manna, S.; Pandey, A.; Singh, S.P.; Komarala, V.K. Role of additive-assisted texturing on surface morphology and interface defect density in silicon heterojunction solar cells. Appl. Phys. A 2025, 131, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Pandey, A.; Alam, S.; Manna, S.; Sadhukhan, S.; Singh, S.P.; Komarala, V.K. Role of wafer resistivity in silicon heterojunction solar cells performance: Some insights on carrier dynamics. Sol. Energy 2025, 299, 113702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittmann, C.; Messmer, P.; Schindler, F.; Polzin, J.; Richter, A.; Weiss, C.; Schubert, M.C.; Janz, S.; Drießen, M. Effective In Situ TOPC on Gettering of Epitaxially Grown Silicon Wafers during Bottom Solar Cell Fabrication. Sol. RRL 2025, 9, 2400908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chen, R.; Chan, C.; Sun, L.; Cheng, Y.; Song, N.; Okamoto, K.; et al. Silver-lean screen-printing metallisation for industrial TOPCon solar cells: Enabling an 80% reduction in silver consumption. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 288, 113654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejci, M.; Hurni, J.; Genç, E.; Čech, J.; Kuliček, J.; Ukraintsev, E.; Haušild, P.; Rezek, B.; Haug, F.-J. Influence of firing temperature and silver–aluminum paste intermixing on front contact quality and performance of TOPCon silicon solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2026, 296, 114085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CellThickness | 130 μm | Bulk Resistivity | 1–13 Ω·cm |

| Rseries | 0.001 Ω·cm2 | Lifetime | 5–30 ms |

| Rshunt | 106 Ω·cm2 | FSF Non-Contact J0 | 0.3 fA·cm−2 |

| P-poly Thickness | 340 nm | Emitter Contact J0 | 10 fA·cm−2 |

| P-poly DopingDensity | 5 × 1019 cm−3 | Emitter Non-Contact J0 | 0.3 fA·cm−2 |

| N-poly Thickness | 280 nm | BSF Contact J0 | 1 fA·cm−2 |

| N-poly DopingDensity | 3 × 1020 cm−3 | BSF Non-Contact J0 | 0.3 fA·cm−2 |

| Al2O3 Thickness | 5 nm | Emitter Width | 693–322 μm |

| SiNx Thickness | 70 nm | BSF Width | 165–537 μm |

| NFinger Width | 26 μm | FingerNumber | 140–300 |

| NFinger Width | 27 μm | BusbarNumber | 10 |

| Busbar Width | 114 μm | GapSkin Width | 40–100 μm |

| SiNx Thickness (nm) | JR (mA/cm2) | JA (mA/cm2) | JT (mA/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 55 | 0.46 | 0.07 | 43.22 |

| 60 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 43.27 |

| 65 | 0.39 | 0.07 | 43.30 |

| 70 | 0.39 | 0.07 | 43.29 |

| 75 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 43.27 |

| 80 | 0.46 | 0.08 | 43.22 |

| Rear-Side Morphologies | SiNx Thickness (nm) | Bulk Resistivity (Ω·cm) | Minority-Carrier Lifetime (ms) | Gap Region Width (μm) | p/n Width Ratio | Figure Number | η (%) | Bifaciality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upright pyramids | 70 | 5 | 10 | 75 | 2.6 | 260 | 27.26 | 90.7 |

| Upright pyramids | 70 | 5 | 10 | 75 | 2.6 | 140 | 27.06 | 93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, F.; Jiang, Z.; Xie, Y.; Xie, T.; Zhang, J.; Hao, X.; Zeng, G.; Yuan, Z.; Wu, L. Bifaciality Optimization of TBC Silicon Solar Cells Based on Quokka3 Simulation. Materials 2026, 19, 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020405

Yang F, Jiang Z, Xie Y, Xie T, Zhang J, Hao X, Zeng G, Yuan Z, Wu L. Bifaciality Optimization of TBC Silicon Solar Cells Based on Quokka3 Simulation. Materials. 2026; 19(2):405. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020405

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Fen, Zhibin Jiang, Yi Xie, Taihong Xie, Jingquan Zhang, Xia Hao, Guanggen Zeng, Zhengguo Yuan, and Lili Wu. 2026. "Bifaciality Optimization of TBC Silicon Solar Cells Based on Quokka3 Simulation" Materials 19, no. 2: 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020405

APA StyleYang, F., Jiang, Z., Xie, Y., Xie, T., Zhang, J., Hao, X., Zeng, G., Yuan, Z., & Wu, L. (2026). Bifaciality Optimization of TBC Silicon Solar Cells Based on Quokka3 Simulation. Materials, 19(2), 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020405