Acoustic Performance of Stone Mastic Asphalts with Crumb Rubber and Polymeric Additives in Warm, Dry Climates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Noise Generation and Traffic Noise Assessment

2.1. Noise Generation

- Air pumping: the air trapped in the cavities of the texture and between the tire tread and the pavement is compressed and expelled violently, generating very significant acoustic pulses between 1 and 4 kHz. Winroth, J. et al. [35] support the recommendation of “negative” textures and connected voids to reduce the aerodynamic component.

- Horn effect: The geometry formed by the sidewall and the wearing surface acts as an amplifier of the noise generated in the contact zone, with increases of several dB [36].

- Tire cavity noise: the internal volume of the tire acts as a resonator and a peak usually appears around 180–220 Hz, depending on size and pressure. It is excited by impacts and irregularities and modulates the total spectrum [19].

- Wet pavement. The noise level increases by approximately 15 dB due to the presence of water [36]. In another study conducted in Portugal, Freitas et al. [37] measured an increase of 6–7.5 dB in passenger cars and 3–5 dB in heavy vehicles on consecutive sections of porous and dense pavement. In Cai et al. [38], also on wet road surfaces, the increase was 10 dB, 5–6 dB, and 4 dB for light, medium, and heavy vehicles, respectively. Even with sound-absorbing, draining, or porous asphalt (PA) pavement, the presence of water increases the TPIN. According to [39], the pavements ranked from highest to lowest noise reduction are: a draining pavement in dry conditions, a dense pavement in dry conditions, a wet or damp draining pavement, and, lastly, a wet dense pavement.

- Vibration of the tread blocks: the tread blocks move in and out of the footprint, periodically loading and unloading and exciting vibrations that emit sound. The stiffness of the compound, the tread geometry and the macrotexture of the pavement determine the amplitude and frequency (typically 0.8–2 kHz for cars). Larsson et al. [40] model the dynamic behavior of tread blocks and their coupling with pavement roughness, enabling the design of textures that minimize block vibration.

- Stick-slip: at the microscale, rubber alternates between sticking to and slipping off the peaks of the texture. This phenomenon generates broadband vibrations, which increase with effective roughness and tangential force, for example during acceleration, braking and cornering [41].

- Roughness impact: when the pavement texture has megatexture (e.g., bumps or joints) or wavelengths comparable to the size of the studs, slower excitations (i.e., low frequencies) and spectrum modulations are created. Del Pizzo et al. [42] corroborate the idea that a well-designed macrotexture, together with moderate porosity, reduces mechanical and aerodynamic excitation.

- Tire structural resonances: [28] The tire rims, plies and sidewalls all have their own modes. When these are fed by texture excitation, specific bands of the sound spectrum increase.

2.2. Traffic Noise Assessment

3. Strategies for the Reduction in Traffic Noise Impact

- Careful planning and traffic management that separates traffic from noise-sensitive areas. According to Lay [13], noise problems can be avoided, mainly by planning strategies, zoning controls and building regulations, which means, respectively, adopting measures such as keeping traffic routes away from noise-sensitive land-uses; preventing noise-sensitive uses from being located near traffic routes, or requiring buildings in noise-sensitive uses to be appropriately located, designed and insulated. An alternative solution is introducing noise-tolerant land-uses, which may be expensive as it will usually involve purchasing noise-affected properties and selling them to new residents who are less concerned with the noise level. The at-source factor that can most reduce noise problems is traffic management since it can achieve less, slower and smoother traffic flow. Additionally, noise can be reduced with fewer noisy vehicles, particularly noisy trucks. For example, the objective of the EU Silence Project [46] is to advise city authorities on types and packages of traffic flow measures and driver assistance systems which can be used to reduce noise from road traffic.

- Attenuating the impact of noise that has already been generated, using noise barriers that are placed between the source of the noise and the perceiver of the noise. Once noise has been generated, it can be reduced (i.e., attenuated) by noise barriers, which may be earth mounds, the faces of cuttings, crib walls, rock walls, concrete walls, or timber fences, as detailed below.

- Reducing noise prior to its generation, i.e., minimizing noise generated at its source by acting on the vehicle’s propulsion system, aerodynamic noise, and TPIN.

3.1. Earthworks

3.2. Tree Belts

3.3. Noise Barriers

3.4. Actions on Vehicles

3.5. Low-Noise Pavements

4. SMA Mixtures

Description

5. Comparative Study of SMA Mixtures

5.1. Need of the Study

5.2. Data

5.2.1. Data Filtering

5.2.2. Data Used for the Study

- Scenario 1: A-8058 between Seville and Coria (Figure 5). SMA mixtures were modified with end-of-life tires (ELTs), laid in different proportions.

- Scenario 2: A-376 between Seville and Utrera (Figure 6). In this case, the mixtures were modified with plastic, nylon and ELTs in different proportions. The AC-16 surf mixture reference was also laid.

5.3. Analysis Methodology

- CPX response variable (dB (A)): level measured per campaign and lane. It is denoted as CPXij, where i is the campaign (0, 3, 6, 12, 18, or 24 months) and j is the section/lane.

- Predictors (all at section and campaign level):

- ○

- MPD [mm]: average depth of macrotexture.

- ○

- Voids [%]: in situ porosity assigned by mix family.

- ○

- Additives [%]: percentage of modification with ELT powder and/or plastic (0; 0.5; 1; 1.5). Modelled as a continuous variable to estimate the marginal effect per percentage point.

- ○

- Months [month]: age since in-service (0–24). Includes polishing/pore cleaning/early stabilization processes.

- ○

- Tair [°C]: ambient temperature during auscultation (22–26 °C).

Statistical Model

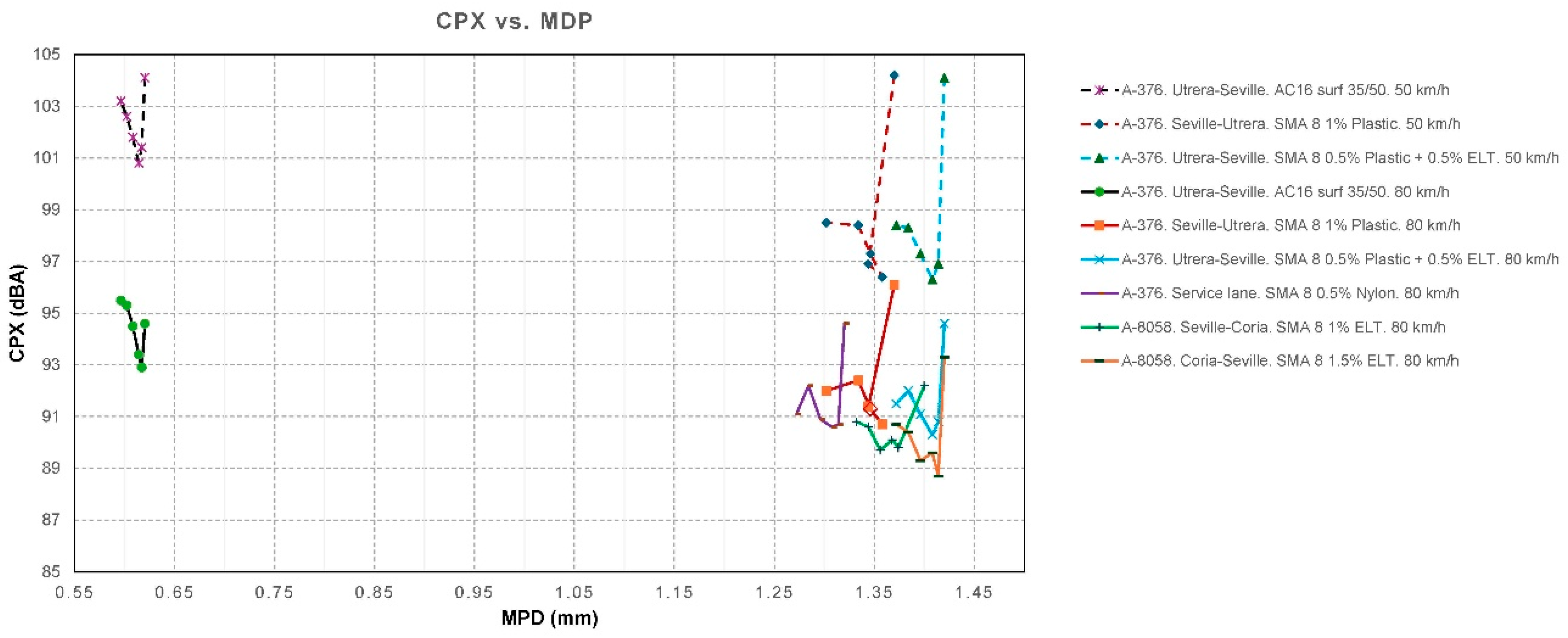

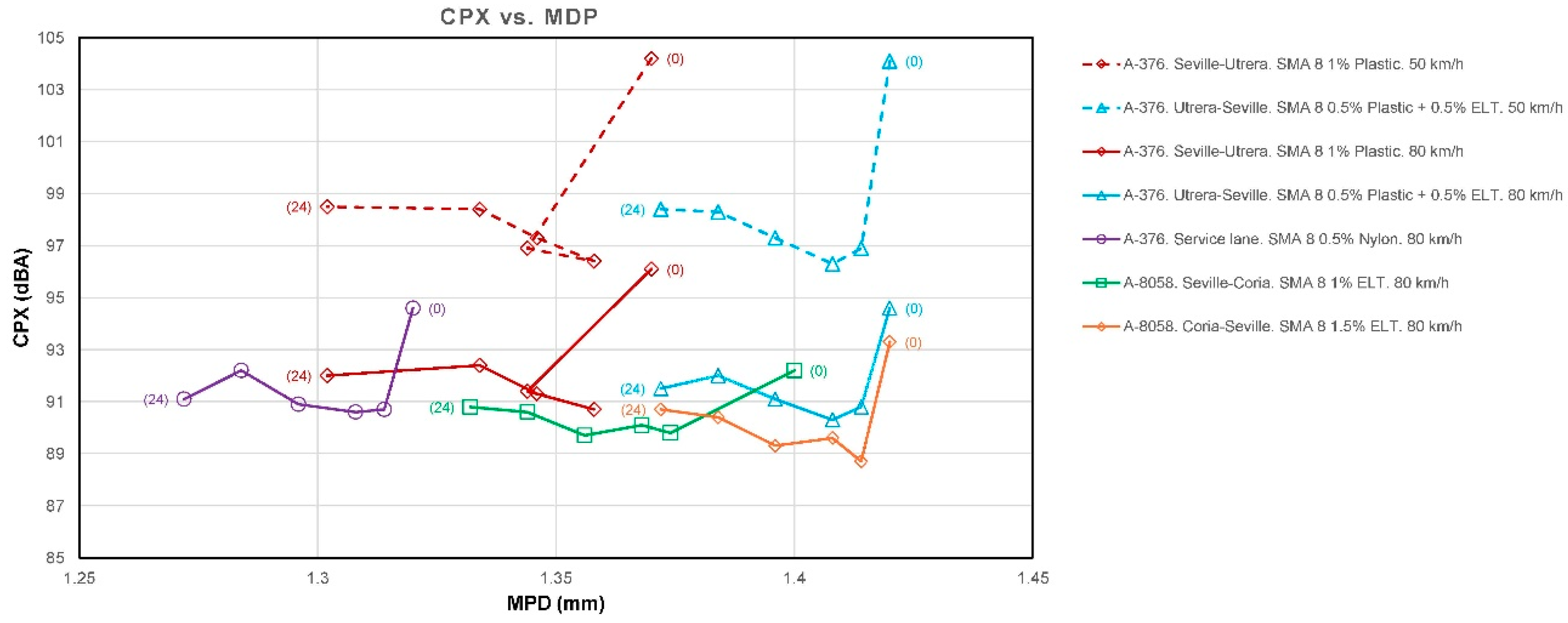

- The factor for MDP is β1 = −2.437 dB/mm. This means that, provided all other factors remain constant, a higher MPD indicates a lower CPX. In a typical range, macrotexture values are between 0.6 and 1.4 mm. Moving from the lower to the upper end of this range implies a difference of 0.8 mm, which, according to the model, represents a decrease of 0.8·(−2.437) =−1.95 dB. This is consistent with the physical hypothesis: an “optimal” macrotexture reduces air pumping and tire block excitation in the range where TPIN dominates.

- A high correlation between macrotexture values and the void index has been observed, and therefore, only one of them should be considered to draw more accurate conclusions and avoid collinearity between variables. In the developed model, it is macrotexture (rather than void content) the variable that defines CPX.

- The factor for additives is β3 = −1177 dB per 1%. This result indicates that adding 1.0% additives reduces the noise level by approximately 1.18 dB compared to the absence of rubber. This data provides us with one of the first conclusions of the study: the clear acoustic benefit of adding rubber or plastic to this type of mixture.

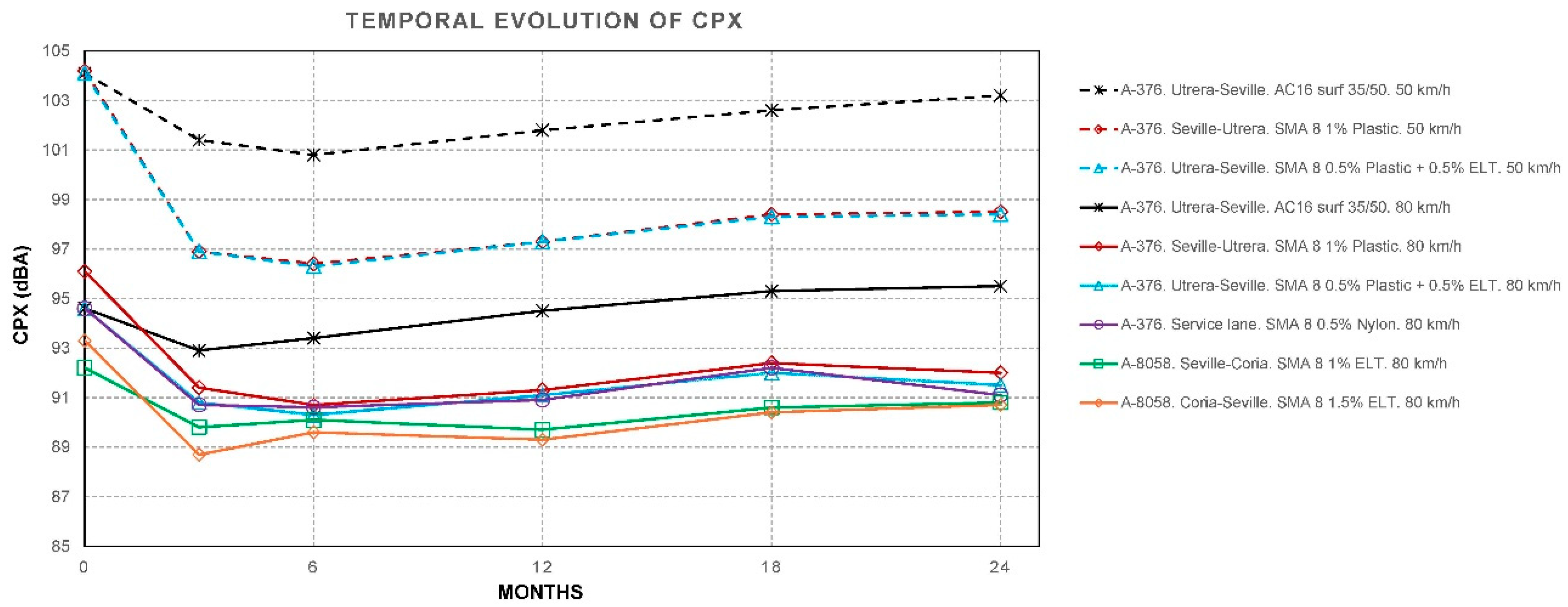

- β4 = −0.0329 dB/month. This value, approximately −0.40 dB per year, reflects the shape of the observed data graphs (Figure 7), which show a decline during the first few months, followed by stabilization. However, while this result is reasonable for these time intervals, extrapolating it to many years is not recommended.

- β5 = −0.123 dB/°C. At higher air temperatures, slightly less noise is produced, with an approximate reduction of 1.23 dB for every 10 °C increase. This is because the rubber and binder become softer and reduce some of the vibration.

6. Discussion

- SMAs provide substantial initial noise reduction compared to dense mixes (AC),

- Surface parameters, such as macrotexture (MPD) and voids, are determining factors.

- Within two years, the CPX does not worsen. It even improves slightly in hot and dry climates. These trends are consistent with European experience: the initial advantage of low-noise pavements (3–6 dB) is well documented, although the magnitude and persistence depend on the type of mixture and the climate. In the Netherlands and Denmark, porous asphalt starts at –4 to –6 dB and shows annual losses of ~0.2–0.33 dB per year. Less porous materials, such as SMA, tend to stabilize their response provided there is no severe clogging [75,76].

6.1. Analysis Methodology MPD and Voids

6.2. Effect of Additives

6.3. Temporal Evolution of CPX

6.4. Temperature

6.5. Design Implications for Spain and Incorporation into PG-3

6.6. Future Works

7. Conclusions

- SMA mixtures containing rubber reduce CPX by 4–6 dB compared to dense AC16. This is consistent with the results from the Life Soundless project.

- Of all the analyzed variables, the percentage of rubber is one of the most significant. According to the analysis, increasing the rubber content by 1% reduces CPX by 1.18 decibels, approximately.

- In terms of construction time, none of the analyzed sections show increases greater than 3 dB in 24 months, so it can be stated that the minimum acoustic life exceeds three years.

- The authors recommend further studies to confirm that, upon completion of works in Mediterranean climates, the MPD value should exceed 1.25 mm and the void percentage should exceed 11%. These studies should be a part of more comprehensive research on SMA, with the aim of defining the parameters of these mixtures to be eventually included in Spanish regulations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADOT | Arizona Department of Transportation |

| AVAS | Acoustic Vehicle Alerting System |

| BBTM | Very Thin Bituminous Concrete (Béton Bitumineux Très Mince) |

| CEDEX | Centro de Estudios y Experimentación de Obras Públicas (Spain) Centre for Studies and Experimentation of Public Works (Spain) |

| CEDR | Conference of European Directors of Road |

| CPX | Close Proximity |

| EU | European Union |

| ELT | End-of-life tire |

| FHWA | Federal Highway Administration |

| MFOM | Ministerio de Transportes y Movilidad Sostenible (Spain) Spanish Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility |

| MPD | Mean Profile Depth |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PA | Porous Asphalt |

| PG-3 | General Technical Specifications for Road and Bridge Works. (Spain) |

| RD | Royal Decree |

| SMA | Stone Mastic Asphalt, also known as Stone Matrix Asphalt |

| SPB | Statistical Pass By |

| TPIN | Tire-pavement interaction noise |

| WHO | World Health Organization. |

| ZOAB | Dutch acronym for porous asphalt |

References

- World Health Organization and European Commission. Burden of Disease from Environmental Noise: Quantification of Healthy Life Years Lost in Europe; Joint of Research Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kempen, E.; Casas, M.; Pershagen, G.; Foraster, M. WHO Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region: A Systematic Review on Environmental Noise and Cardiovascular and Metabolic Effects: A Summary. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basner, M.; Babisch, W.; Davis, A.; Brink, M.; Clark, C.; Janssen, S.; Stansfeld, S. Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health. Lancet 2014, 383, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Paunović, K. WHO Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region: A Systematic Review on Environmental Noise and Cognition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anne, O.H.; Knol, B.; Jantunen, M.; Lim, T.-A.; Conrad, A.; Rappolder, M.; Carrer, P.; Fanetti, A.-C.; Kim, R.; Buekers, J.; et al. Environmental Burden of Disease in Europe: Assessing Nine Risk Factors in Six Countries. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recio, A.; Linares, C.; Banegas, J.R.; Díaz, J. The short-term association of road traffic noise with cardiovascular, respiratory, and diabetes related mortality. Environ. Res. 2016, 150, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blickley, J.L.; Patricelli, G.L. Impacts of Anthropogenic Noise on Wildlife: Research Priorities for the Development of Standards and Mitigation. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 2010, 13, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 2002/49/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 June 2002 Relating to the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise–Declaration by the Commission in the Conciliation Committee on the Directive Relating to the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32002L0049 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- European Union. Commission Directive (EU) 2015/996 of 19 May 2015 Establishing Common Noise Assessment Methods According to Directive 2002/49/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2015/996/oj/eng (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Spain. Law 37/2003 of 17 November on Noise, Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), No. 276. 18 November 2003. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2003/11/17/37/con (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Spain. Royal Decree 1513/2005 of 16 December Implementing Law 37/2003 of 17 November on Noise, Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), No. 301. 17 December 2005. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2005/12/16/1513/con (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Spain. Royal Decree 1367/2007 of 19 October Implementing Law 37/2003 of 17 November on Noise, Regarding Acoustic Zoning, Quality Objectives and Acoustic Emissions, Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), No. 254. 20 October 2007. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2007/10/19/1367/con (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Lay, M.G. Handbook of Road Technology, 4th ed.; Spon Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Conference of European Directors of Roads (CEDR). Action Plan 2025–2027. CEDR. Available online: https://www.cedr.eu/action-plan-2025-2027 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Priede, T. Origins of automotive vehicle noise. J. Sound Vib. 1971, 15, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitkus, A.; Andriejauskas, T.; Vorobjovas, V.; Jagniatinskis, A.; Fiks, B.; Zofka, E. Asphalt wearing course optimization for road traffic noise reduction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 152, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, U.; Ejsmont, J.A. Tyre/Road Noise Reference Book; Informex: Kisa, Japen, 2002; ISBN 9163126109. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T. Literature review of tire-pavement interaction noise and reduction approaches. J. Vibroengineering 2018, 20, 2424–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckl, M. Tire noise generation. J. Sound Vib. 1986, 100, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Masaeid, H.R.; Al-Hadidi, M.; Gunaratne, M. Effect of Pavement Roughness on Arterial Noise Using Continuous Traffic Monitoring Data. Acoustics 2023, 5, 788–807. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando, S.E. Medidas preventivas y correctoras del ruido de tráfico. In Master en Ingeniería y Gestión Medioambiental 2007/2008; Escuela de Organización Industrial (EOI): Madrid, Spain, 2007/2008. 38p. Available online: https://www.eoi.es/sites/default/files/savia/documents/componente45712.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Reduction of Noise in the Vicinity of Roads (Spanish ed. Reducción del Ruido en el Entorno de las Carreteras), Road Transport Research Series (Madrid: Centro de Publicaciones, Secretaría General Técnica, Ministerio de Obras Públicas, Transportes y Medio Ambiente, 1995), NIPO 161-95-1367, Depósito Legal M-38805-1995, ISBN 84-498-0173-7. Available online: https://cdn.transportes.gob.es/portal-web-transportes/carreteras/normativa_tecnica/15_ruido/1410400_0.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- López-de Abajo, L.; Pérez-Fortes, A.P.; Alberti, M.G.; Gálvez, J.C.; Ripa, T. Sustainability analysis of the M-30 Madrid tunnels and Madrid Río after 14 years of service life. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragh, J. Road Traffic Noise Attenuation by Belts of Trees. J. Sound Vib. 1981, 74, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.-F.; Ling, D.-L. Investigation of the noise reduction provided by tree belts. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 63, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility. Secretariat-General for Land Transport, Guide for the Design and Construction of Acoustic Barriers on Roads; NIPO (Online) 196-24-068-1; NIPO (Print) 196-24-067-6; Legal Deposit M-9828-2024; Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility, Secretariat-General Technical, Publications Centre: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoi, K.H.; Loo, B.P.; Li, X.; Zhang, K. The co-benefits of electric mobility in reducing traffic noise and chemical air pollution: Insights from a transit-oriented city. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, P.; Sandberg, U.; Bendtsen, H.; Bergiers, A. Guidance Manual for the Implementation of Low-Noise Road Surfaces (SILVIA); FEHRL Report 2006/02; FEHRL: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.E. Updated Review of Stone Matrix Asphalt and Superpave® Projects. Transp. Res. Rec. 2003, 1832, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Asphalt Pavement Association (NAPA). Designing and Constructing SMA Mixtures—State-of-the-Practice; Quality Improvement Series 122; National Asphalt Pavement Association: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, G. Stone Mastic Asphalt–A Review of Its Noise-Reducing and Early-Life Skid-Resistance Properties. In Proceedings of the Acoustics 2006, Christchurch, New Zealand, 20–22 November 2006; pp. 319–323. [Google Scholar]

- Gardziejczyk, W.; Motylewicz, M. Noise level in the vicinity of signalized roundabouts. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 46, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Development, Infrastructure and Spatial Planning of the Regional Government of Andalusia. Recommendations on Noise-Reducing Pavements of the LIFE-Soundless Type: New Generation of Asphalt Mixtures with Recycled Materials with High Acoustic Performance and Durability (LIFE14 ENV/ES/000708); Regional Government of Andalusia, with the collaboration of the LIFE Financial Instrument of the European Union: Seville, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Junta de Andalucía, Ministry of Development, Infrastructure and Territory Planning. New Generation of Eco-Friendly Asphalt with Recycled Materials and High Durability and Acoustic Performance: Layman’s Report (LIFE-Soundless LIFE14 ENV/ES/000708); Junta de Andalucía: Seville, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/fomentoinfraestructurasyordenaciondelterritorio/areas/infraestructuras-viarias/proyecto-life-soundless.html (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Winroth, J.; Kropp, W.; Beaurain, J.; Arcos, R. Investigating generation mechanisms of tyre/road noise by separating air-pumping related sources. Appl. Acoust. 2017, 120, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kropp, W.; Larsson, K.; Wullens, F.; Andersson, P. Tyre/road noise generation–modelling and understanding. In Proceedings of the Institute of Acoustics, Southampton, UK, 29–30 March 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, E.; Pereira, P.; de Picado-Santos, L.; Santos, A. Traffic Noise Changes due to Water on Porous and Dense Asphalt Surfaces. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2009, 10, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Zhong, S.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, W. Study of the traffic noise source intensity emission model and the frequency characteristics for a wet asphalt road. Appl. Acoust. 2017, 123, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descornet, G. Vehicle Noise Emission on Wet Road Surfaces. In Proceedings of the INTER-NOISE 2000: 29th International Congress On Noise Control Engineering, Nice, France, 27–30 August 2000. paper no. 1040. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, K.; Kropp, W. The modelling of the dynamic behaviour of tyre tread blocks. Appl. Acoust. 2002, 63, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, B.N.J. Theory of rubber friction and contact mechanics. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 115, 3840–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pizzo, L.G.; Bianco, F.; Teti, L.; Moro, A.; Licitra, G. Influence of texture on tyre/road noise spectra in rubberised pavements. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 159, 107080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11819-2:2017; Acoustics—Measurement of the Influence of Road Surfaces on Traffic Noise—Part 2: The Close-Proximity (CPX) Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 11819-1:2017; Acoustics—Measurement of the Influence of Road Surfaces on Traffic Noise—Part 1: The Statistical Pass-By (SPB) Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ASTM E1845-23; Standard Practice for Calculating Pavement Macrotexture Mean Profile Depth. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- European Commission—CORDIS, SILENCE (FP6)—Quieter Surface Transport in Urban Areas (Project Factsheet), Project ID 516288. (Brussels: European Commission, 2005–2008). Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/516288 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Aylor, D. Noise Reduction by Vegetation and Ground. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1971, 51, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohatkiewicz, J.; Hałucha, M.; Dębiński, M.K.; Jukowski, M.; Tabor, Z. Investigation of acoustic properties of different types of low-noise road surfacers under in situ and laboratory conditions. Materials 2022, 15, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEDR. Noise Reducing Pavements: State of the Art and Practical Guidance; Conference of European Directors of Roads: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Licitra, G.; Cerchiai, M.; Teti, L.; Ascari, E.; Bianco, F.; Chetoni, M. Performance Assessment of Low-Noise Road Surfaces in the LEOPOLDO Project: Comparison and Validation of Different Measurement Methods. Coatings 2015, 5, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheijen, E.; Jabben, J. Effect of Electric Cars on Traffic Noise and Safety; RIVM Letter Report 680300009; National Institute for Public Health and the Environment: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Skov, R.S.H.; Iversen, L.M. Noise from Electric Vehicles–Measurements; Final Report 25 March 2015; Danish Road Directorate: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Laib, F. Acoustic vehicle alerting systems (AVAS) of electric cars and its possible influence on urban soundscapes. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Congress on Acoustics, Aachen, Germany, 9–13 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leupolz, M.; Gauterin, F. Vehicle Impact on Tire Road Noise and Validation of an Algorithm to Virtually Change Tires. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohiduzzaman, M.; Sirin, O.; Kassem, E.; Rochat, J.L. State-of-the-Art Review on Sustainable Design and Construction of Quieter Pavements—Part 1: Traffic Noise Measurement and Abatement Techniques. Sustainability 2016, 8, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühlmann, E.; Sandberg, U.; Berge, T.; Goubert, L.; Schlatter, F. Call 2018 Noise and Nuisance: STEER Final Report—STEER: Strengthening the Effect of Quieter Tyres on European Roads; CEDR Contractor Report 2022-07; Conference of European Directors of Roads: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; ISBN 979-10-93321-69-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, S.; Yu, F.; Sun, D.; Sun, G. A comprehensive review of tire–pavement noise: Generation mechanism, measurement methods, and quiet asphalt pavement. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish Road Directorate. Noise Reducing Pavements (Proceedings DRI–DWW Workshop, Rungstedgaard, 23–24 Nov 2006; Rehosted 2025). Available online: https://www.vejdirektoratet.dk/sites/default/files/2025-06/noise_reducing_pavements_0.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Veisten, K. Cost-Benefit Analysis of Low-Noise Pavements: Dust into the Calculations. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2011, 12, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, J.C. Caracterización cuantitativa de las mezclas SMA (Stone Asphalt Mastic). In Proceedings of the Actas del XXII Congreso Ibero-Latinoamericano del Asfalto (CILA), Granada, Spain, 22–26 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- National Asphalt Pavement Association (NAPA). Advances in the Design, Production, and Construction of Stone Matrix (Mastic) Asphalt; Special Report 223; National Asphalt Pavement Association: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, J.C. TRL Report 314: Road Trials of Stone Mastic Asphalt and Other Thin Surfacings; Transport Research Laboratory: Berkshire, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Serfass, J.-P.; Samanos, J. Stone mastic asphalt for very thin wearing courses. In Proceedings of the 71st Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC, USA, 12 January 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, V.F.; Terán, F.; Luong, J.; Paje, S.E. Functional Performance of Stone Mastic Asphalt Pavements in Spain: Acoustic Assessment. Coatings 2019, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardziejczyk, W.; Plewa, A.; Pakholak, R. Effect of Addition of Rubber Granulate and Type of Modified Binder on the Viscoelastic Properties of Stone Mastic Asphalt Reducing Tire/Road Noise (SMA LA). Materials 2020, 13, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, T.; Dravitzki, V.; Carpenter, P.; McIver, I.; Jackett, R. The Long-term Acoustic Performance of New Zealand Standard Porous Asphalt; NZ Transport Agency Research Report 626; NZTA: Wellington, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- EN 13108 5:2016; Bituminous Mixtures—Material Specifications—Part 5: Stone Mastic Asphalt. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- Costa, A.; Loma, J.; Hidalgo, M.E.; Hergueta, J.A.; Sánchez, F.; Lanchas, S.; Núñez, R.; Jiménez, R.; Pérez, F.E.; Botella, R.; et al. Sustainable and Eco-Friendly SMA(Stone Mastic Asphalt)‘ (Mezclas SMA (Stone Mastic Asphalt), Sostenibles y Medioambientalmente Amigables. IX Jornada Nacional de ASEFMA, Comunicación 08. 2014. Available online: https://asefma.es/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/08.-Mezclas-SMA-v1.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025). (In Spanish).

- Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility. PG-3: General Technical Specifications for Road and Bridge Works; Consolidated Edition; Technical General Secretariat, Publications Centre: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility. OC 3/2019 on SMA Mixtures; Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sirin, O.; Ohiduzzaman, M.; Kassem, E. Influence of temperature on tire-pavement noise in hot climates: Qatar case. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriejauskas, T.; Vaitkus, A.; Čygas, D. Tyre/road noise spectrum analysis of ageing low-noise pavements. In Proceedings of the Euronoise 2018, Creta, 2018; Available online: https://www.euronoise2018.eu/docs/papers/451_Euronoise2018.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Gardziejczyk, W. The effect of time on acoustic durability of low noise pavements–The case studies in Poland. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 44, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaberg, J.; Schmidt, B.; Bendtsen, H. Technical Performance and Long-Term Noise Reduction of Porous Asphalt Pavements; Report 112; Danish Road Institute: Roskilde, Denmark, 2001; ISBN 87-90145-90-9. [Google Scholar]

- Danish Road Directorate (Vejdirektoratet), Noise Reducing Pavements, Copenhagen, 2005 (Rev. Posteriores en Portal VD): “Porous Asphalt: Initial 4–6 dB Reduction … Gradual Clogging ⇒ Loss … Terminal Still 1–3 dB.” Vejdirektoratet.dk. Available online: https://www.vejdirektoratet.dk/api/drupal/sites/default/files/publications/noise_reducing_pavements.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Vuye, C.; Bergiers, A.; Vanhooreweder, B. The Acoustical Durability of Thin Noise Reducing Asphalt Layers. Coatings 2016, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/TS 13471-1:2017; Acoustics—Temperature Influence on Tyre/Road Noise Measurement—Part 1: Correction for Temperature when Testing with the CPX Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Asefma. Mezclas SMA (Stone Mastic Asphalt), Sostenibles y Durables. Madrid. 2014. Available online: https://www.itafec.com/descargas/monografia-17-de-asefma-mezclas-sma-stone-mastic-asphalt (accessed on 25 October 2025).

| Asphalt Mixture | Noise Level dB(A) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SMA11 (Spain) | 95.1 | [21] |

| SMA11S (Czechia) | 98.2 | [16] |

| EACC 8 mm (exposed aggregate concrete) | 98.0 | [16] |

| Double-layer porous asphalt (DPA) | ≈93.0 | [28] |

| Mixture | MPD0 (mm) | Air Voids (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SMA 8 1% ELT | 1.35 | 12.5 |

| SMA 8 1.5% ELT | 1.35 | 10.0 |

| SMA 8 0.5% Nylon | 1.20 | 8.0 |

| SMA 8 1% Plastic | 1.35 | 10.0 |

| SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 1.35 | 11.5 |

| AC16 surf 35/50 | 0.80 | 3.0 |

| Lane | Speed | Mixture | CPX | MPD | % Additive | Months | Air Temp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-376 Seville-Utrera | 50 | SMA 8 1% Plastic | 104.2 | 1.37 | 1 | 0 | 24 |

| A-376 Seville-Utrera | 50 | SMA 8 1% Plastic | 96.9 | 1.344 | 1 | 3 | 26 |

| A-376 Seville-Utrera | 50 | SMA 8 1% Plastic | 96.4 | 1.358 | 1 | 6 | 22 |

| A-376 Seville-Utrera | 50 | SMA 8 1% Plastic | 97.3 | 1.346 | 1 | 12 | 24 |

| A-376 Seville-Utrera | 50 | SMA 8 1% Plastic | 98.4 | 1.334 | 1 | 18 | 22 |

| A-376 Seville-Utrera | 50 | SMA 8 1% Plastic | 98.5 | 1.302 | 1 | 24 | 24 |

| Lane | Speed | Mixture | CPX | MPD | % Additive | Months | Air Temp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 50 | SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 104.1 | 1.42 | 1 | 0 | 24 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 50 | SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 96.9 | 1.414 | 1 | 3 | 26 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 50 | SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 96.3 | 1.408 | 1 | 6 | 22 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 50 | SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 97.3 | 1.396 | 1 | 12 | 24 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 50 | SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 98.3 | 1.384 | 1 | 18 | 22 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 50 | SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 98.4 | 1.372 | 1 | 24 | 24 |

| A-376 Utrera-Sevilla | 50 | AC16 surf 35/50 | 104.1 | 0.62 | 0 | 0 | 24 |

| A-376 Utrera-Sevilla | 50 | AC16 surf 35/50 | 101.4 | 0.617 | 0 | 3 | 26 |

| A-376 Utrera-Sevilla | 50 | AC16 surf 35/50 | 100.8 | 0.614 | 0 | 6 | 22 |

| A-376 Utrera-Sevilla | 50 | AC16 surf 35/50 | 101.8 | 0.608 | 0 | 12 | 24 |

| A-376 Utrera-Sevilla | 50 | AC16 surf 35/50 | 102.6 | 0.602 | 0 | 18 | 22 |

| A-376 Utrera-Sevilla | 50 | AC16 surf 35/50 | 103.2 | 0.596 | 0 | 24 | 24 |

| Lane | Speed | Mixture | CPX | MPD | % Additive | Months | Air Temp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-376 Seville-Utrera | 80 | SMA 8 1% Plastic | 96.1 | 1.37 | 1 | 0 | 24 |

| A-376 Seville-Utrera | 80 | SMA 8 1% Plastic | 91.4 | 1.344 | 1 | 3 | 26 |

| A-376 Seville-Utrera | 80 | SMA 8 1% Plastic | 90.7 | 1.358 | 1 | 6 | 22 |

| A-376 Seville-Utrera | 80 | SMA 8 1% Plastic | 91.3 | 1.346 | 1 | 12 | 24 |

| A-376 Seville-Utrera | 80 | SMA 8 1% Plastic | 92.4 | 1.334 | 1 | 18 | 22 |

| A-376 Seville-Utrera | 80 | SMA 8 1% Plastic | 92 | 1.302 | 1 | 24 | 24 |

| Lane | Speed | Mixture | CPX | MPD | % Additive | Months | Air Temp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 80 | SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 94.6 | 1.42 | 1 | 0 | 24 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 80 | SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 90.8 | 1.414 | 1 | 3 | 26 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 80 | SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 90.3 | 1.408 | 1 | 6 | 22 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 80 | SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 91.1 | 1.396 | 1 | 12 | 24 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 80 | SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 92 | 1.384 | 1 | 18 | 22 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 80 | SMA 8 0.5% Plastic + 0.5% ELT | 91.5 | 1.372 | 1 | 24 | 24 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 80 | AC16 surf 35/50 | 94.6 | 0.62 | 0 | 0 | 24 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 80 | AC16 surf 35/50 | 92.9 | 0.617 | 0 | 3 | 22 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 80 | AC16 surf 35/50 | 93.4 | 0.614 | 0 | 6 | 22 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 80 | AC16 surf 35/50 | 94.5 | 0.608 | 0 | 12 | 24 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 80 | AC16 surf 35/50 | 95.3 | 0.602 | 0 | 18 | 22 |

| A-376 Utrera-Seville | 80 | AC16 surf 35/50 | 95.5 | 0.596 | 0 | 24 | 24 |

| Lane | Speed | Mixture | CPX | MPD | % Additive | Months | Air Temp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-376 Service Lane | 80 | SMA 8 0.5% Nylon | 94.6 | 1.32 | 0.5 | 0 | 22 |

| A-376 Service Lane | 80 | SMA 8 0.5% Nylon | 90.7 | 1.314 | 0.5 | 3 | 26 |

| A-376 Service Lane | 80 | SMA 8 0.5% Nylon | 90.6 | 1.308 | 0.5 | 6 | 22 |

| A-376 Service Lane | 80 | SMA 8 0.5% Nylon | 92.2 | 1.284 | 0.5 | 18 | 22 |

| A-376 Service Lane | 80 | SMA 8 0.5% Nylon | 90.9 | 1.296 | 0.5 | 12 | 24 |

| A-376 Service Lane | 80 | SMA 8 0.5% Nylon | 91.1 | 1.272 | 0.5 | 24 | 24 |

| Lane | Speed | Mixture | CPX | MPD | % Aditive | Months | Air Temp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-8058 Seville-Coria | 80 | SMA 8 1% ELT | 92.2 | 1.4 | 1 | 0 | 22 |

| A-8058 Seville-Coria | 80 | SMA 8 1% ELT | 89.8 | 1.374 | 1 | 3 | 26 |

| A-8058 Seville-Coria | 80 | SMA 8 1% ELT | 90.1 | 1.368 | 1 | 6 | 22 |

| A-8058 Seville-Coria | 80 | SMA 8 1% ELT | 89.7 | 1.356 | 1 | 12 | 24 |

| A-8058 Seville-Coria | 80 | SMA 8 1% ELT | 90.6 | 1.344 | 1 | 18 | 22 |

| A-8058 Seville-Coria | 80 | SMA 8 1% ELT | 90.8 | 1.332 | 1 | 24 | 24 |

| Lane | Speed | Mixture | CPX | MPD | % Aditive | Months | Air Temp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-8058 Coria-Seville | 80 | SMA 8 1.5% ELT | 93.3 | 1.42 | 1.5 | 0 | 24 |

| A-8058 Coria-Seville | 80 | SMA 8 1.5% ELT | 88.7 | 1.414 | 1.5 | 3 | 26 |

| A-8058 Coria-Seville | 80 | SMA 8 1.5% ELT | 89.6 | 1.408 | 1.5 | 6 | 22 |

| A-8058 Coria-Seville | 80 | SMA 8 1.5% ELT | 89.3 | 1.396 | 1.5 | 12 | 24 |

| A-8058 Coria-Seville | 80 | SMA 8 1.5% ELT | 90.4 | 1.384 | 1.5 | 18 | 22 |

| A-8058 Coria-Seville | 80 | SMA 8 1.5% ELT | 90.7 | 1.372 | 1.5 | 24 | 24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Campuzano-Ríos, J.; Jorquera-Lucerga, J.J. Acoustic Performance of Stone Mastic Asphalts with Crumb Rubber and Polymeric Additives in Warm, Dry Climates. Materials 2026, 19, 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020260

Campuzano-Ríos J, Jorquera-Lucerga JJ. Acoustic Performance of Stone Mastic Asphalts with Crumb Rubber and Polymeric Additives in Warm, Dry Climates. Materials. 2026; 19(2):260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020260

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampuzano-Ríos, Jesús, and Juan José Jorquera-Lucerga. 2026. "Acoustic Performance of Stone Mastic Asphalts with Crumb Rubber and Polymeric Additives in Warm, Dry Climates" Materials 19, no. 2: 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020260

APA StyleCampuzano-Ríos, J., & Jorquera-Lucerga, J. J. (2026). Acoustic Performance of Stone Mastic Asphalts with Crumb Rubber and Polymeric Additives in Warm, Dry Climates. Materials, 19(2), 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020260