2.1. Flowsheet Architecture

The process flowsheet tracks the circulation of peening media as a dynamic working mix composed of three characteristic modes: (1) as-manufactured, (2) conditioned, and (3) worn. As media are cycled through repeated impacts, they undergo morphological degradation via fracture, abrasion, and plastic deformation. When particles reach a state of excessive wear, they are removed from the system by a classifier and discarded as debris. To maintain system equilibrium, discarded media are replenished with fresh (as-manufactured) particles based on a mass-balance threshold, resulting in a continuous renewal process that stabilizes the working mix distribution over time.

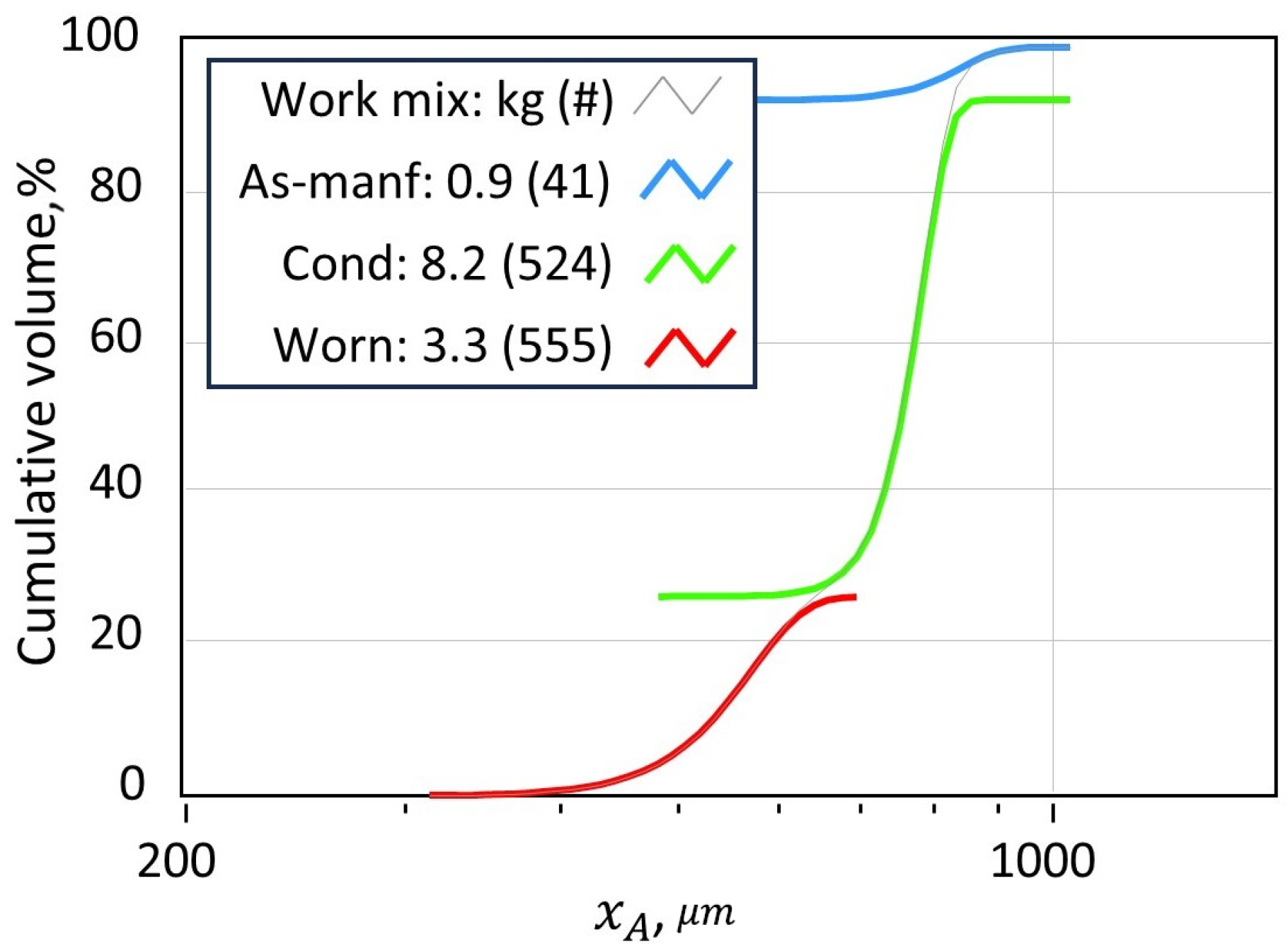

Each mode is further characterized by distinct size and shape distributions, quantified using DIA and parameterized using stretched exponential fits. As shown in

Figure 1 and summarized in

Table 1, the size of media decreases monotonically with wear, while the tightest distributions occur in the conditioned mode. Shape anisotropy, described by aspect ratio (AR), increases in uniformity during the transition from as-manufactured to conditioned media, but becomes broader again in the worn mode due to fracture and distortion.

The working mix model captures this evolving distribution as a three-mode mixture, with the relative contribution of each mode governed by the age of particles in the system. Transitions between modes are described using empirical wear parameters, which may be directly measured using a cyclical-impact apparatus (Ervin Tester, Ervin Inc., Adrian, MI, USA) or inferred through multimodal decomposition of dynamic image analysis (DIA) data from working-mix samples [

13]. Each mode is modeled using a Weibull lifecycle function, where the cumulative distribution of transfers,

, is given in terms of the characteristic number of impact cycles

and a stretching exponent

m:

This formulation enables probabilistic modeling of inter-mode transfer, where the likelihood of a particle transitioning out of its current mode increases with cumulative impact exposure.

For example, fresh media introduced into the system begin in the as-manufactured mode. According to the wear parameters in

Table 2, these particles transition to the conditioned mode with a relatively low characteristic impact count (

) and a low stretching exponent (

), indicating rapid conditioning of most of the media with a diffuse tail. Once in the conditioned mode, media are more resilient, with a higher durability (

). The stretching exponent (

) delays the conditioned → worn transition, with the effect that conditioned particles tend to remain stable over many impacts before transitioning into the worn state. Worn particles degrade with an intermediate profile before exiting the system as debris, with

and

. Overall, the wear parameters define a cycle of degradation, where particles are continuously added, reshaped, and ultimately removed, with the recharge strategy maintaining a dynamic equilibrium across the three modes. This evolving distribution directly influences the impact energy spectrum delivered to the peened surface.

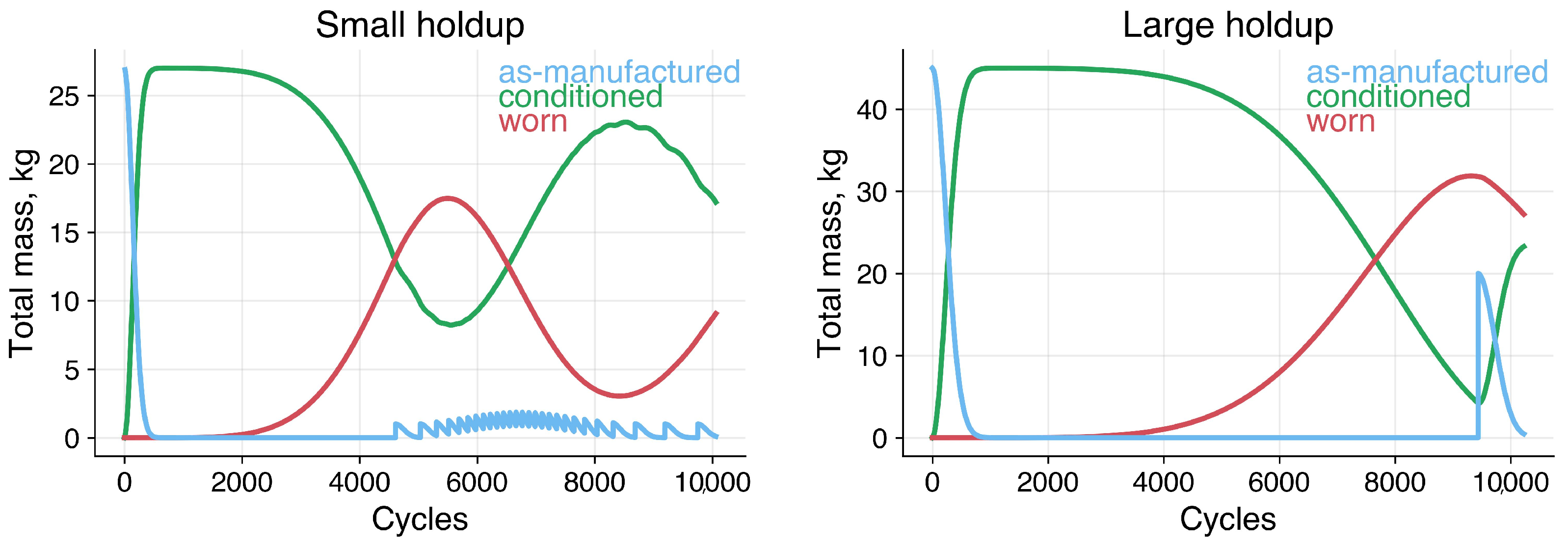

2.1.1. Work Mix Dynamics

The mix of modes is dynamic and depends on the media recharge criteria. The current version of the flowsheet must have a heel of media in a recycle bin. When the mass in that bin drops below a threshold value, a recharge of the as-manufactured media occurs. If the recharge mass is small relative to the total working mix, i.e., frequent and small recharges, the working mix is relatively stable with dampened fluctuations occurring primarily between the conditioned and worn modes. If the recharge is large and less frequent, the working mix will fluctuate substantially among all three modes. Note, the current flowsheet assumes stable operation of the classifier, i.e., there are no parameters for screening efficiency in the current model.

2.1.2. Archetypal Models for Peening Media

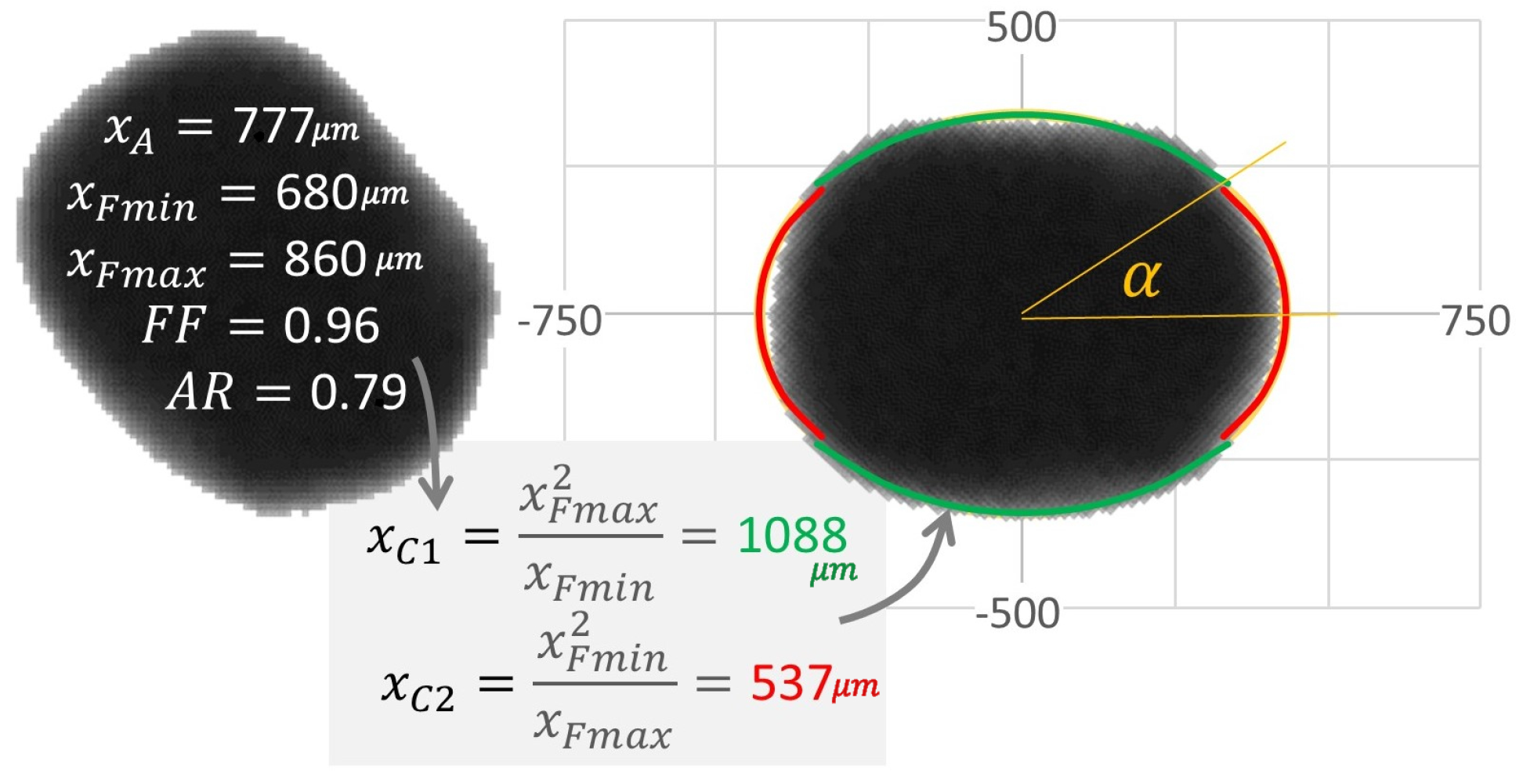

Shape archetypes were used to translate measured shape distributions into effective curvature of peening impacts. Archetypes describe the peening media in terms of their method of manufacture (e.g., cast versus cut wire steel) and level of conditioning. The current work employs an elliptical archetype model for conditioned cut wire, having effective curvature defined by major and minor axes, shown in

Figure 2. Note that unconditioned cut wire has sharper curvature at cut-corners, yet these features are relatively short-lived in a steady-state peening process. While quantitative descriptions of detailed curvature features have been enabled in image analysis [

16], the simpler elliptical archetype shape model was used for the purpose of flowsheet demonstration [

17].

Peening media size and shape effects are selected using a two-step process: (1) random selection of a peening media mass based on the number distribution of the measured area-equivalent size, , and (2) random selection of an elliptical curvature based on an archetypal shape model. In this example, the measured aspect ratio distribution, , is used to estimate the curvature of an elliptical archetype. Empirically, we found and to be uncorrelated within each mode, allowing independent sampling.

To estimate contact curvature, we approximate each particle as an ellipse with semi-major axis

a and semi-minor axis

b, related to the area-equivalent size and aspect ratio by:

The principal radii of curvature at the tips of the ellipse are given by:

which define the elliptical curvatures used in the model:

corresponding to the sharper (minor-axis tip) and flatter (major-axis tip) regions of the particle, respectively.

The relative probability of a peening contact occurring at

versus

depends on the ray length from the center of mass to the point of curvature:

The selection of

versus

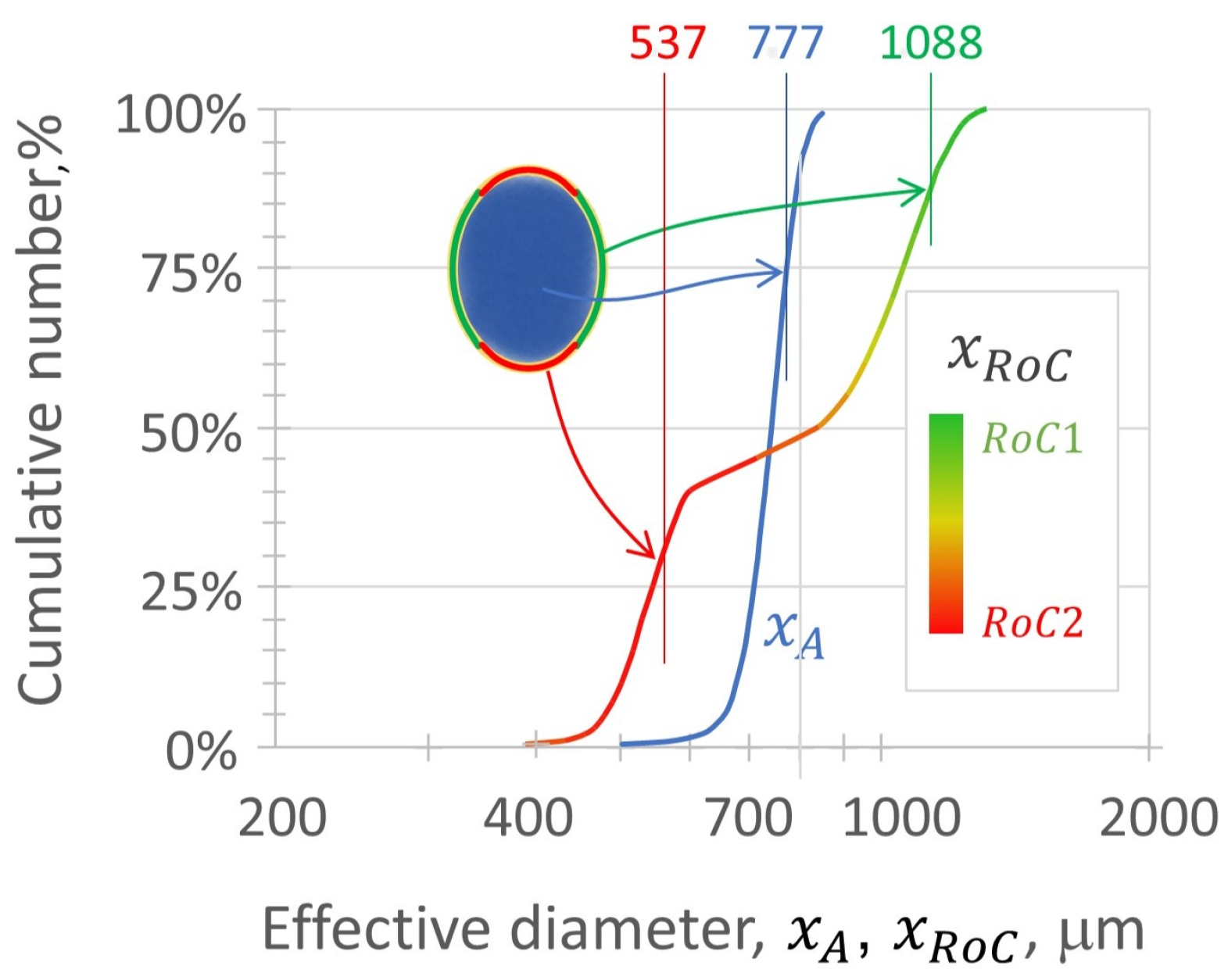

is made by an additional random number call based on these probabilities. Overall, the flowsheet integrates size and shape distributions using a Monte Carlo statistical approach involving three random choices: (1) selection of

, (2) selection of

, and (3) selection of

from the directional curvatures. This provides a distribution of discrete peening events, each having an impact energy and contact curvature. When considered as contacts, the curvature model has the effect of broadening the media distribution (

Figure 3).

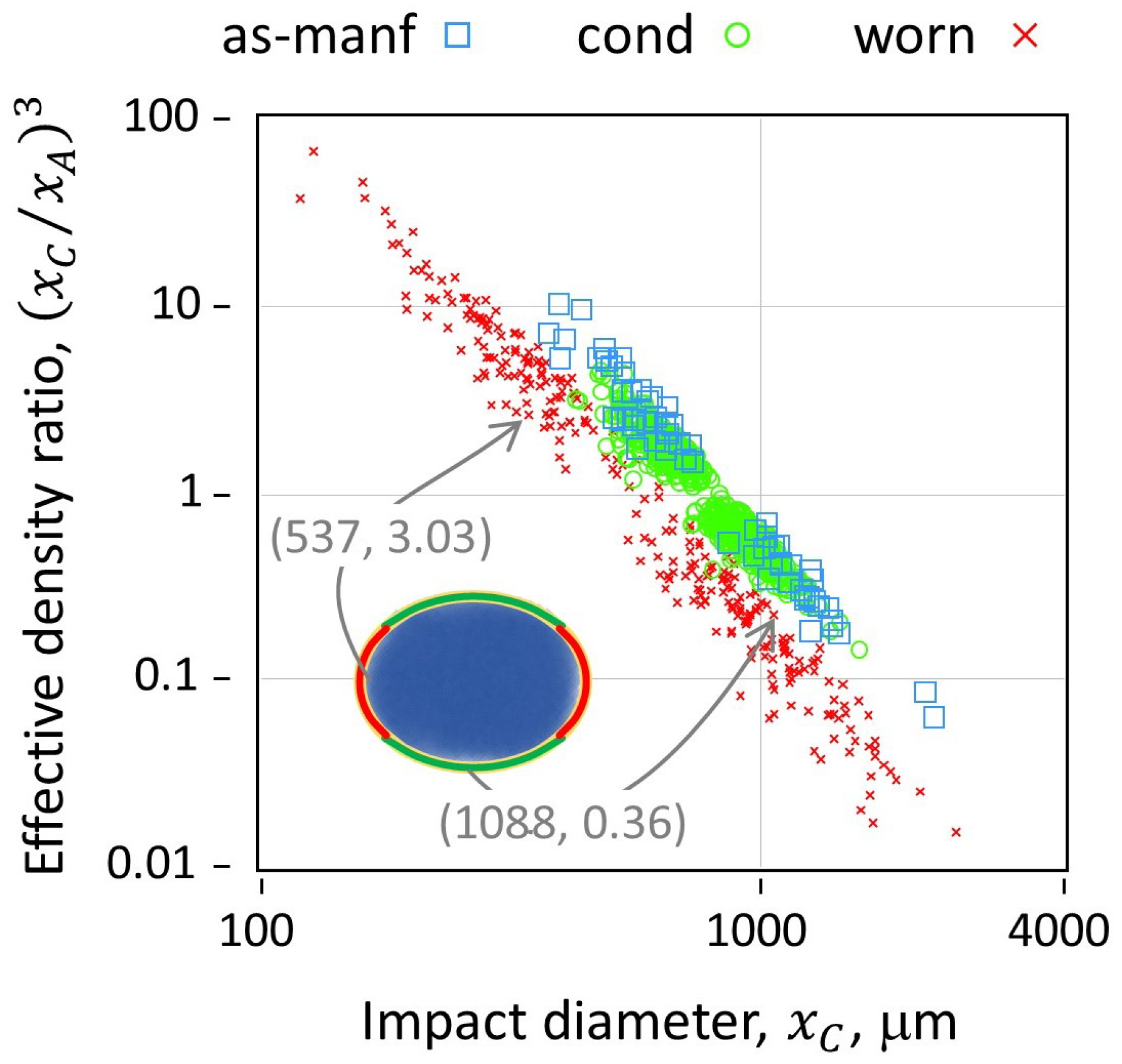

2.1.3. Effective Peening Impact

Each media-substrate impact is modeled as an effective impact between a spherical shot particle having a radius that is equal to the selected radius of curvature, yet having a mass that is consistent with the actual shot size. The actual mass is based on the material density, e.g., 7.8 g/mL for CW32 media, multiplied by the volume of the shot particle obtained from its projected area,

A, measured by DIA,

. To maintain this mass with a sphere that was adjusted to a different radius of curvature, an effective density ratio is applied,

. When

, the effective density ratio < 1; when

, the effective density ratio > 1 (

Figure 4). This suggests a broadening of the impact stress distribution, with large-curvature impacts having relatively broader contact area and lower impact stress compared to small-curvature impacts.

2.1.4. Peening Coverage

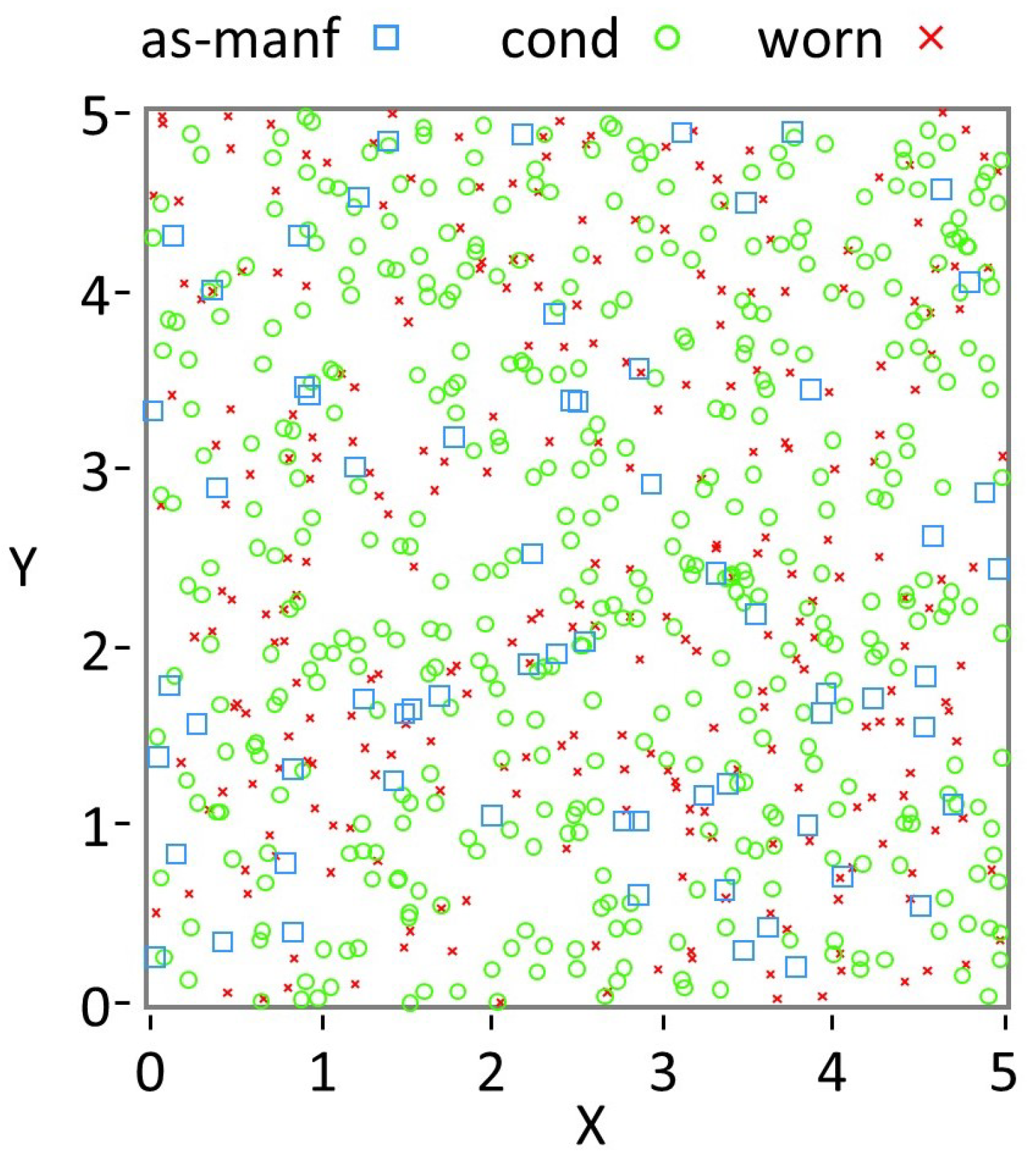

The flowsheet simulation generates periodic snapshots of peening coverage based on the prescribed media mass flow rate, treated surface area, and a defined coverage time interval. Impacts contributing to the average areal mass density are sampled over a representative surface element, with impact locations modeled using randomized coordinates.

The coverage map is displayed as point contacts by mode within the work mix distribution (

Figure 5). The data shown in

Figure 4 provide initial conditions for more detailed residual stress calculations via Finite Element Modeling (FEM) and reductions thereof, essentially correlating the distribution of paired input parameters (

) to a resultant stress field induced by the random coverage (

Figure 5) of said impacts.

2.2. FEM-Based Convolutional Neural Network

2.2.1. RVE Finite Element Analysis

Snapshots of peening coverage generated by the flowsheet (

Figure 5) were used as initial conditions for finite element simulations. These coverage maps, defined by sampled impact positions and media descriptors (

), provide the basis for correlating stochastic impact fields with resultant residual stress states and for constructing the training dataset for the ConvLSTM surrogate.

Each FEM simulation drew coverage maps from the flowsheet while varying mass flow rate and impact velocity within the ranges given in

Table 3, with fixed constants summarized in

Table 4. The full factorial design yielded 9 simulations. Radii of curvature were assigned from elliptical archetypes based on measured aspect ratios. Shots were treated as rigid, impacts were temporally staggered, and a node-to-surface contact model without friction was applied. For each simulation, residual stress fields were recorded after the series of impacts. These stored fields, paired with their corresponding impact histories from the flowsheet, form the basis for the patch-level dataset used to train and evaluate the ConvLSTM surrogate.

Johnson–Cook isotropic hardening was used to model the elasto-plastic response of the SAE 1070 Almen strip material, as described by Ghanbari et al. [

18] (

Table 5). Thermal effects were not simulated; peening was treated purely as a cold-working process.

ABAQUS Explicit 2019 [

19] was used to run the peening simulations. A rectilinear mesh of C3D8R elements made up the bulk of the RVE. The simulated RVE was 5 mm × 5 mm × 2 mm in size, with a layer of infinite (CIN3D8) elements at its boundary and base. Grid independence on the basis of total strain energy was observed across all combinations of impact kinetics with a surface element size of 20

m × 20

m × 20

m, in line with guidance by Wang et al. [

20], who observed grid independence with a surface element size of

-th the dimple diameter. For computational efficiency, a biased mesh was employed such that elements farther from the impact surface were larger, with a maximum element size of 20

m × 20

m × 100

m at the base of the substrate.

For this report, we focus on the mean in-plane residual stress, defined as

because it is translationally and rotationally invariant relative to the measurement plane and directly related to the pressure holding a surface crack closed. Future work may also consider the normal Cauchy stress in the

X or 11-direction (

), given its direct analogy to stresses measured with X-ray diffraction [

21,

22], which remains a common quality control metric in industrial shot peening practice. In this work we restrict attention to normal impacts, where the stress state is approximately isotropic within the surface plane; however, off-angle cases may introduce anisotropy into the residual stress field and necessitate directionally dependent descriptors.

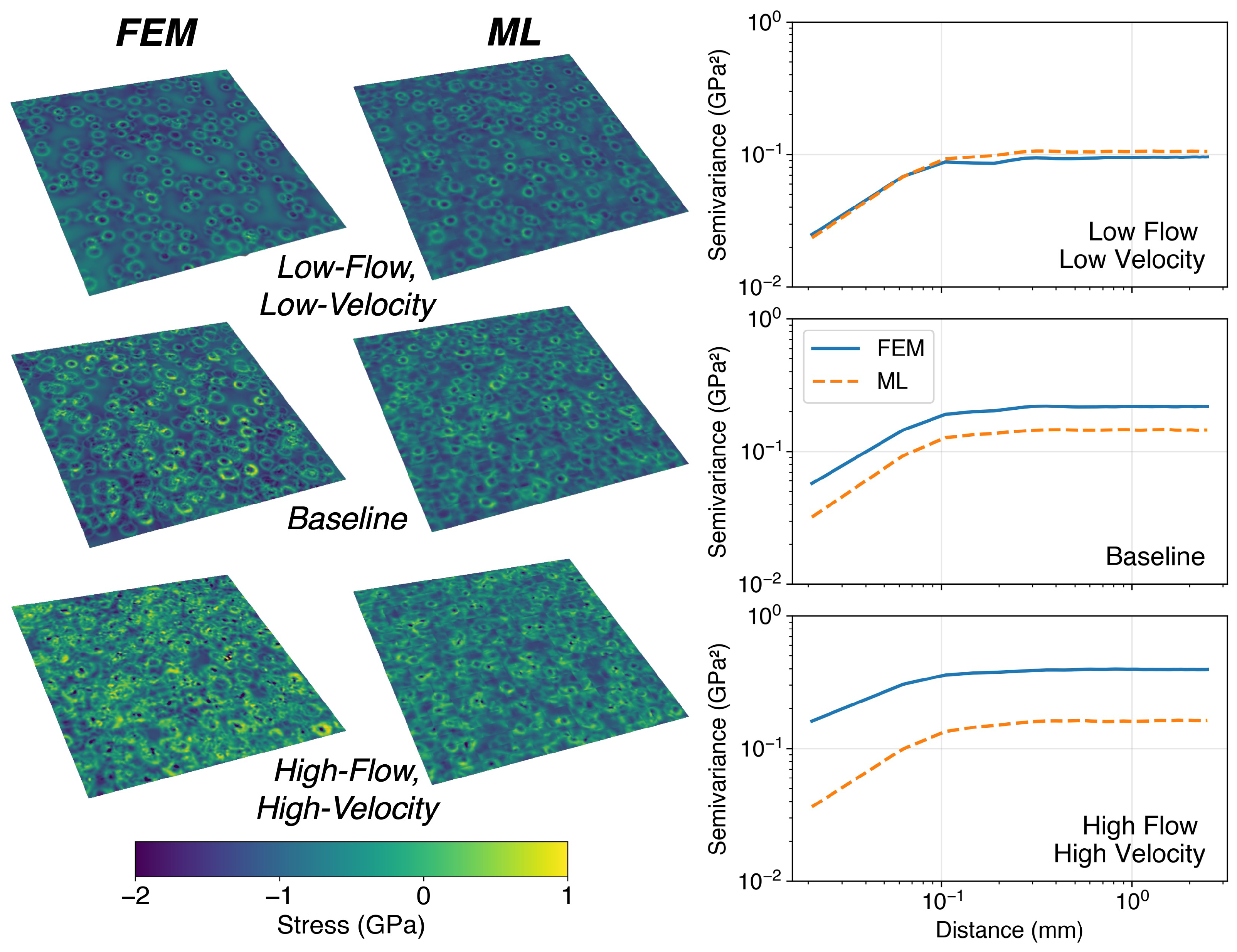

2.2.2. LSTM Convolutional Neural Network FEM Surrogate

In our previous work [

23], we used spectral correction methods to describe residual stress field structure based on reduced-order micromechanical solutions. That approach did not account for impact order, instead relying on linear superposition of impacts. At low impact densities, where overlaps are rare, the model successfully reproduced both the pointwise stress field and its spatial correlation structure. At high impact densities, however, the reduced-order model simplified to a stochastic field with the same mean, variance, and correlation structure as the FEM predictions, but without the ability to resolve pointwise details. To address this limitation, the present work treats the evolution of stresses and surface topography in the shot peening system as a history-dependent process.

We developed an impact-order–aware ConvLSTM surrogate model trained on a set of representative finite element simulations, enabling fast prediction of residual stress fields under arbitrary peening conditions. Training inputs were constructed as spatial energy maps using an Eshelby inclusion analogy, as explored in our recent work [

23]. Each impacting particle was represented by a 2D projection whose footprint was parameterized by the effective contact radius derived from the selected contact curvature rather than the full geometric projection. Within this footprint, the particle’s kinetic energy was distributed uniformly; points outside received zero contribution. Thus, each impact was encoded as a localized scalar energy inclusion capturing the combined effects of particle size, shape, and velocity:

where

and

are the mass and velocity of the

ith particle, and

is the effective contact radius used for input construction. For each stored FEM snapshot, we reconstructed the preceding impact history from the flowsheet and rasterized the corresponding sequence of energy inclusions onto a fixed grid. Each dataset sample consists of a temporally ordered impact sequence paired with the resulting local stress response.

FEM-predicted stress fields were decomposed into local prediction windows to provide training targets for the surrogate model. Each target was defined as a pixel patch of the in-plane residual stress field, corresponding to a neighborhood of approximately at the FEM mesh resolution. Predicting continuous patches simultaneously, rather than individual points, improved the model’s ability to reproduce coherent structures associated with surface plasticity and reduced the numerical model’s tendency to minimize variance across the field. This window size was chosen to balance spatial resolution with computational efficiency, while remaining large enough to capture the stress gradients and local interactions among multiple adjacent impacts. For each RVE and coverage snapshot, the full surface was tiled into overlapping patches using a fixed stride, and patches near free boundaries were excluded to avoid edge artifacts. Patches from all simulations and coverage levels were then pooled, randomly shuffled, and used to assemble the final dataset.

The corresponding model input was an ordered sequence of impact “frames,” each of size pixels, encoding the spatial distribution of particle energy deposition across successive timesteps. The larger input frame ensured that the receptive field encompassed the surrounding impact environment beyond the target window, allowing the network to capture influential impacts just outside the prediction region. Each input–output pair therefore consists of a sequence of T impact-energy frames of size and a corresponding residual stress patch, where T is the number of impacts that intersect the region of interest.

Our network was implemented in TensorFlow [

24]. The architecture, summarized in

Table 6, was designed to balance temporal–spatial modeling capacity with computational efficiency. A per-frame encoder reduced each

impact frame to progressively compressed feature maps (

and

), using

gelu activations to enhance convergence stability without explicit normalization. These encoded sequences were passed to stacked ConvLSTM layers, which captured both intra-frame spatial correlations and inter-frame temporal dependencies. The decoder then upsampled the

latent representation back to a

output window, using bilinear interpolation followed by convolutional refinement to reconstruct fine-scale detail. A final

convolution produced the predicted residual stress field. This encoder–ConvLSTM–decoder formulation enabled mappings from evolving impact fields to localized stress responses without the computational burden of full-field predictions.

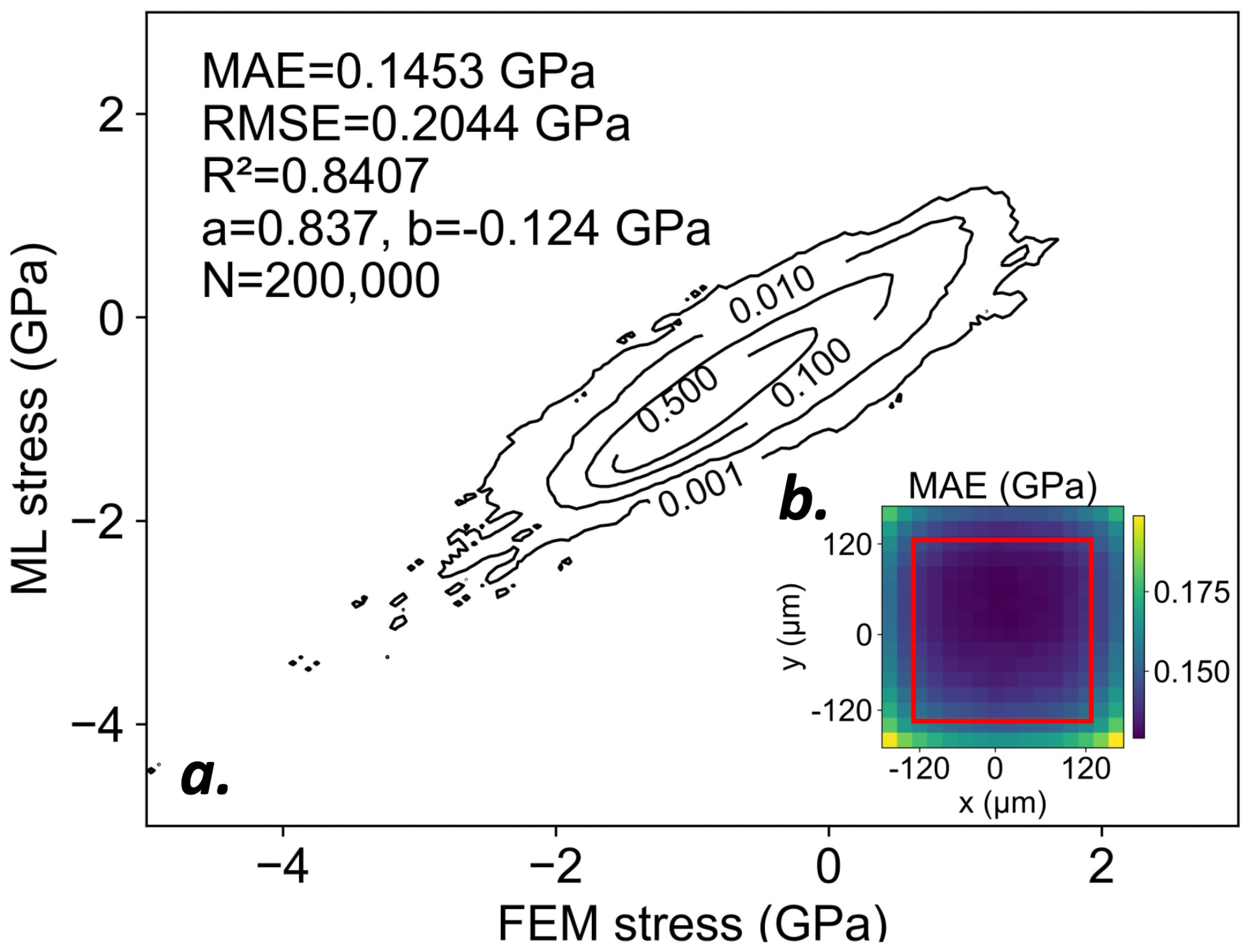

We employed a custom loss function that combined the mean squared error (MSE) of the stress patches with the difference in variance between the ML predictions and the FEM targets. This formulation rewarded point-wise accuracy while penalizing the model’s tendency to underestimate field-level variance. Both components of the loss are dimensionally consistent (). The dataset was partitioned into a 75:25 training–test split. Patches were assigned to the training or test set at the sample level, such that each input–output pair was used exclusively for training or evaluation. Training used the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of , progressively reduced to as losses plateaued. After 42 epochs, the model achieved a final MSE of and an average variance difference of on the test set.