Effects of SiC Particle Size on SiCp/Al Composite During Vacuum Hot Pressing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

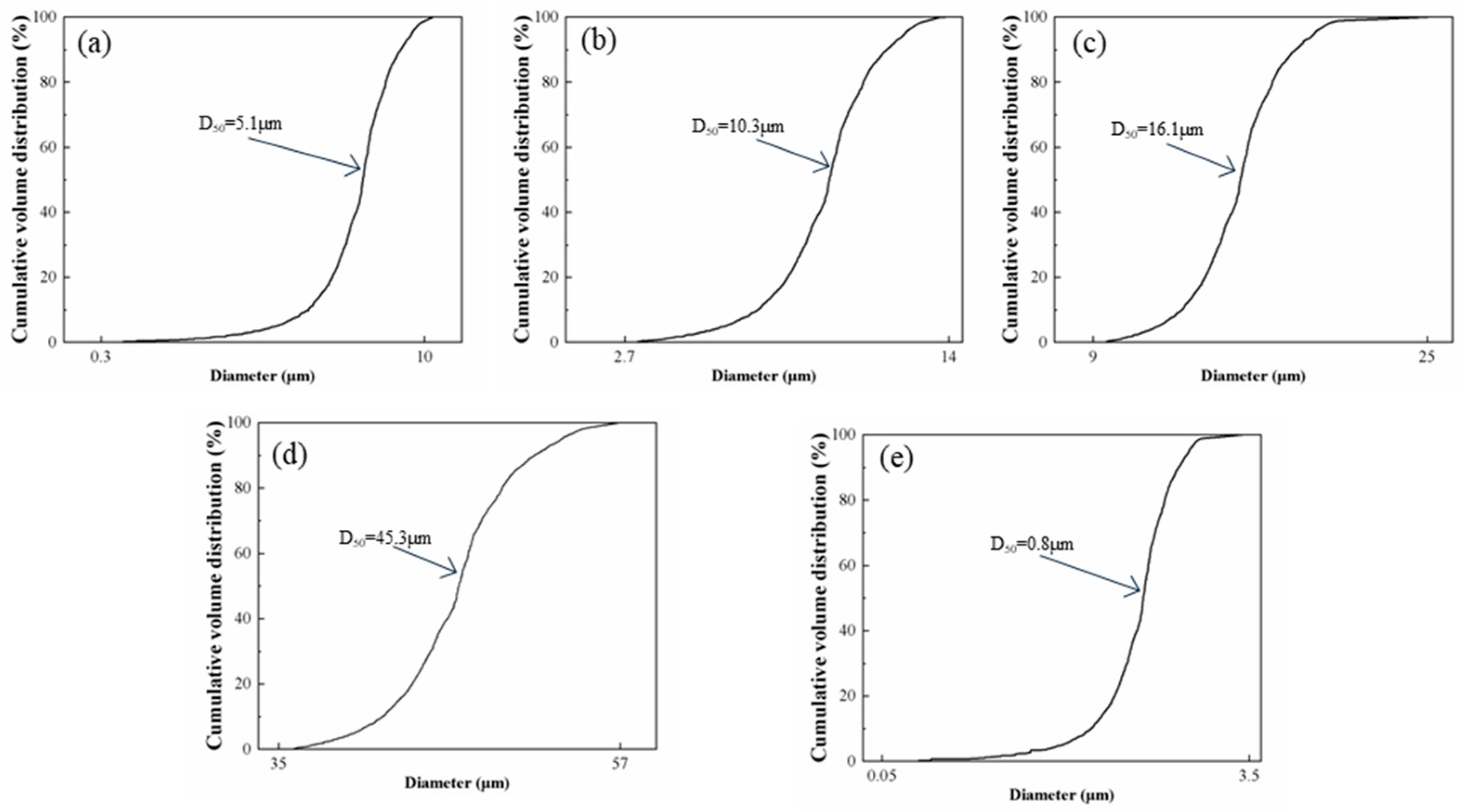

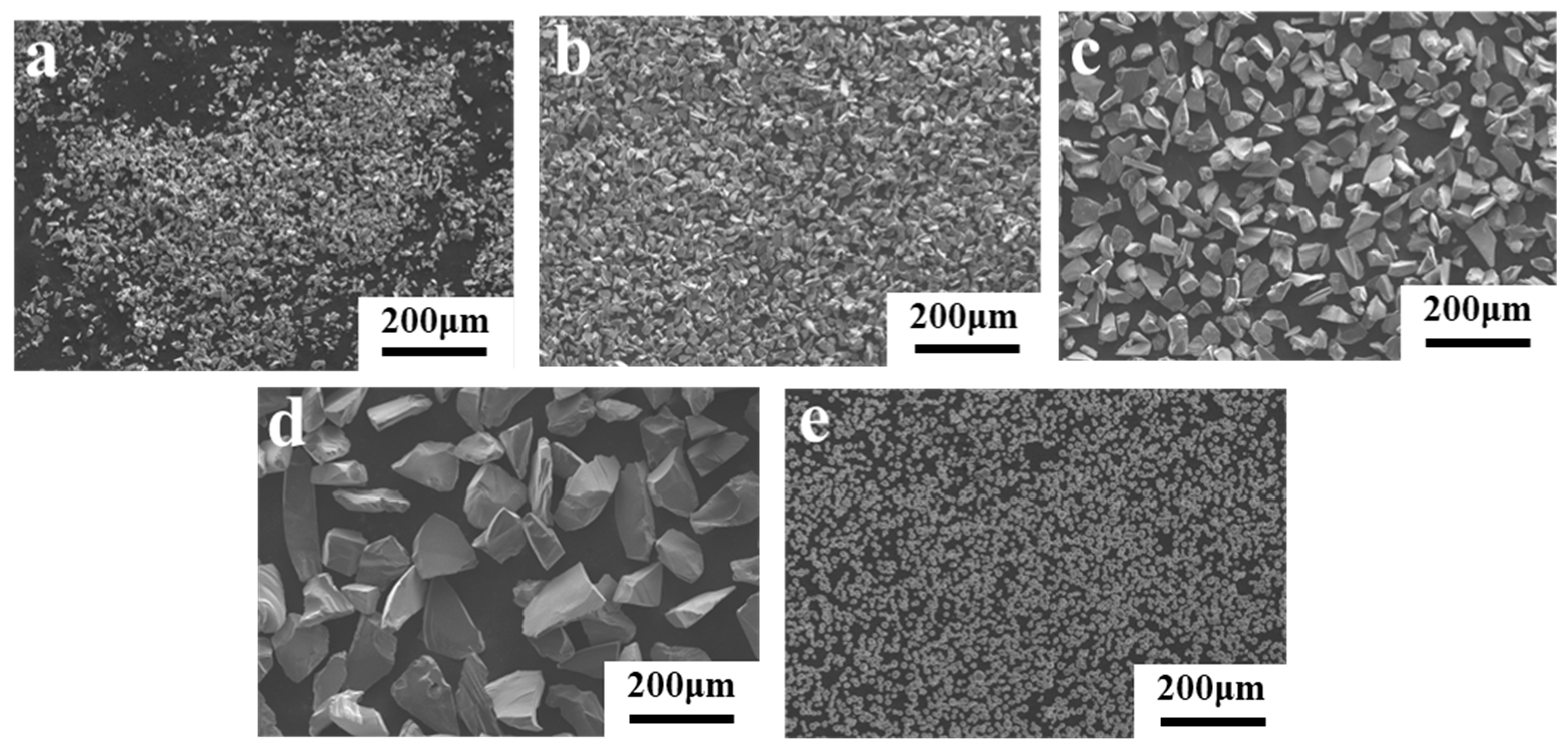

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Vacuum Hot-Pressing Process

2.3. Material Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Densification Behavior of SiCp/Al Composites

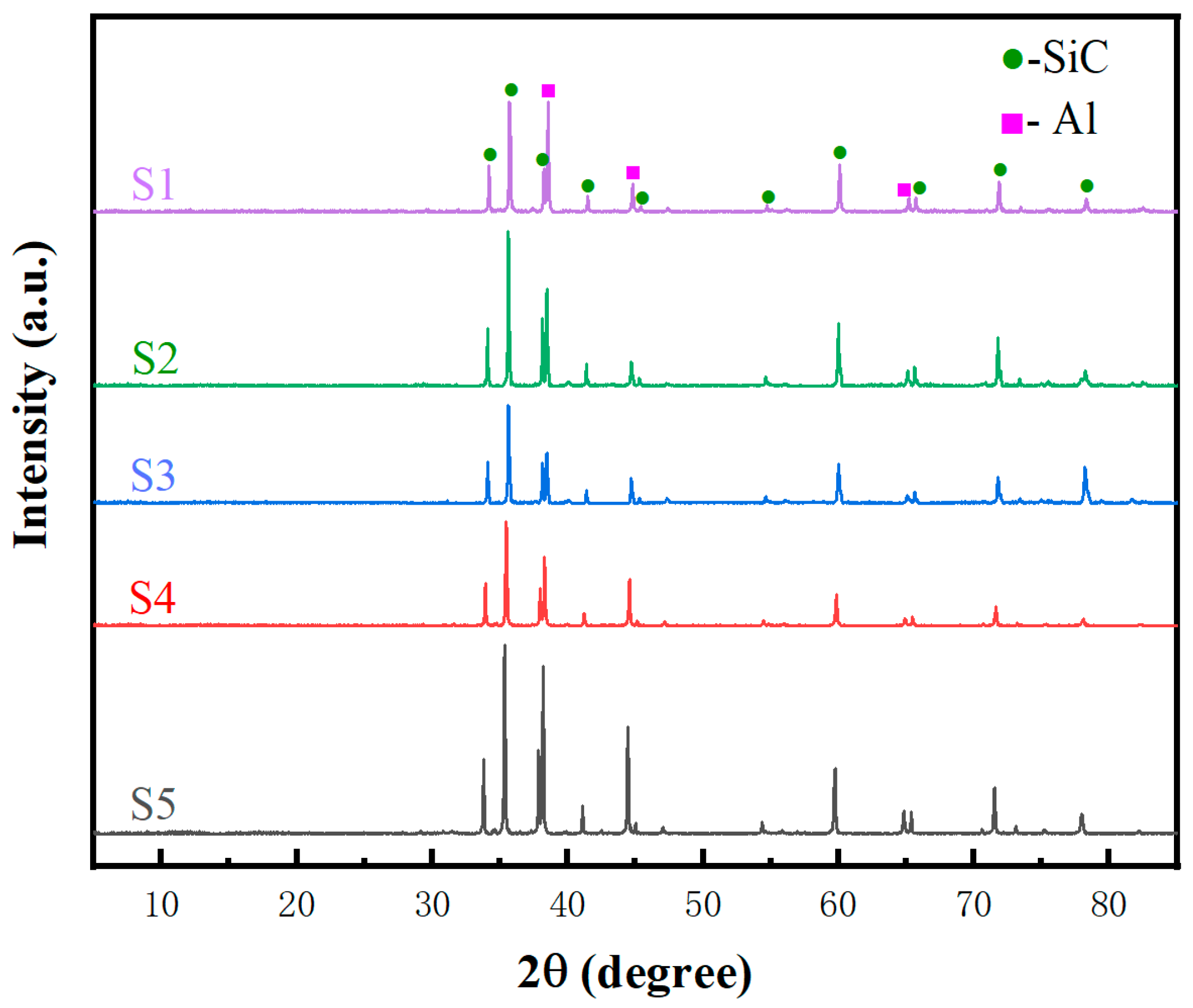

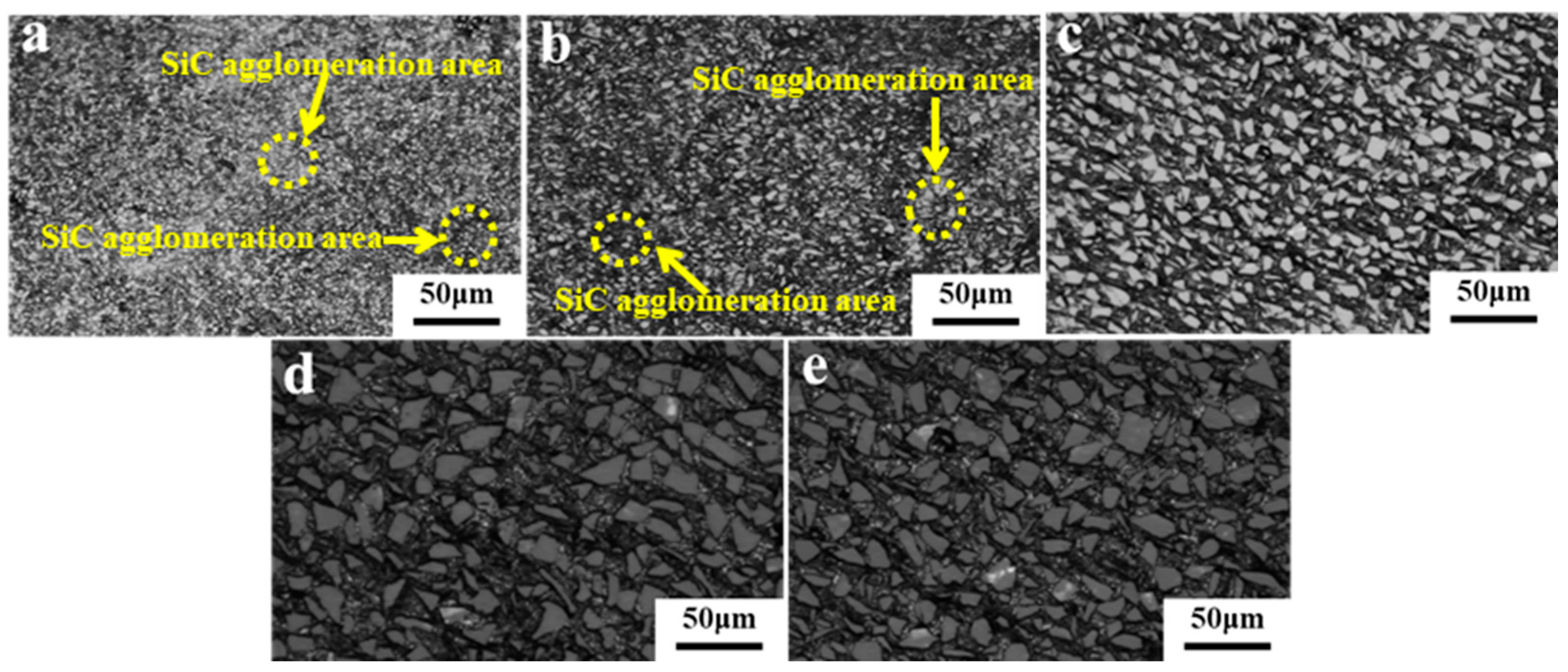

3.2. Phase Composition and Microstructure Evolution of SiCp/Al Composites

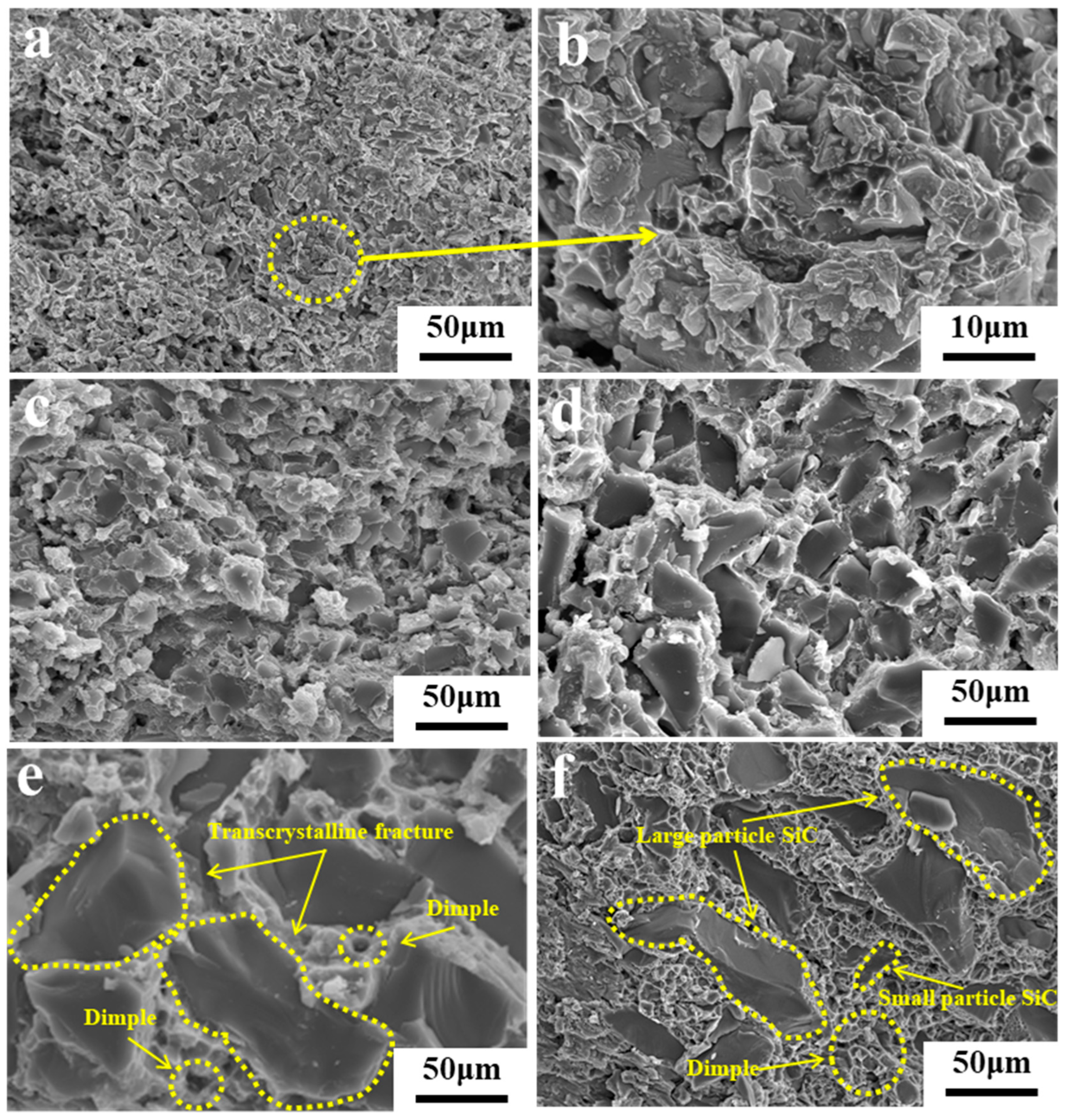

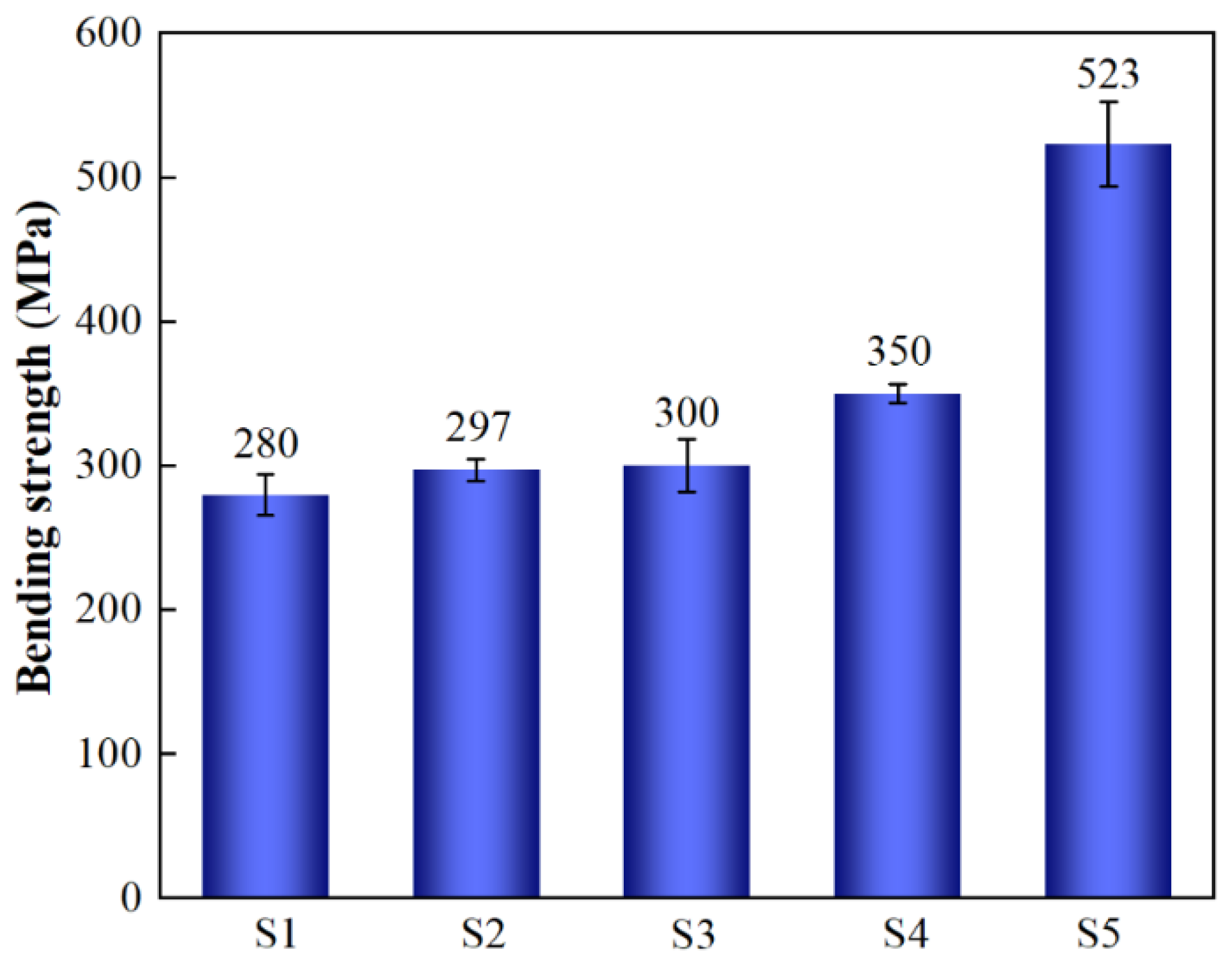

3.3. Mechanical Properties of SiCp/Al Composites

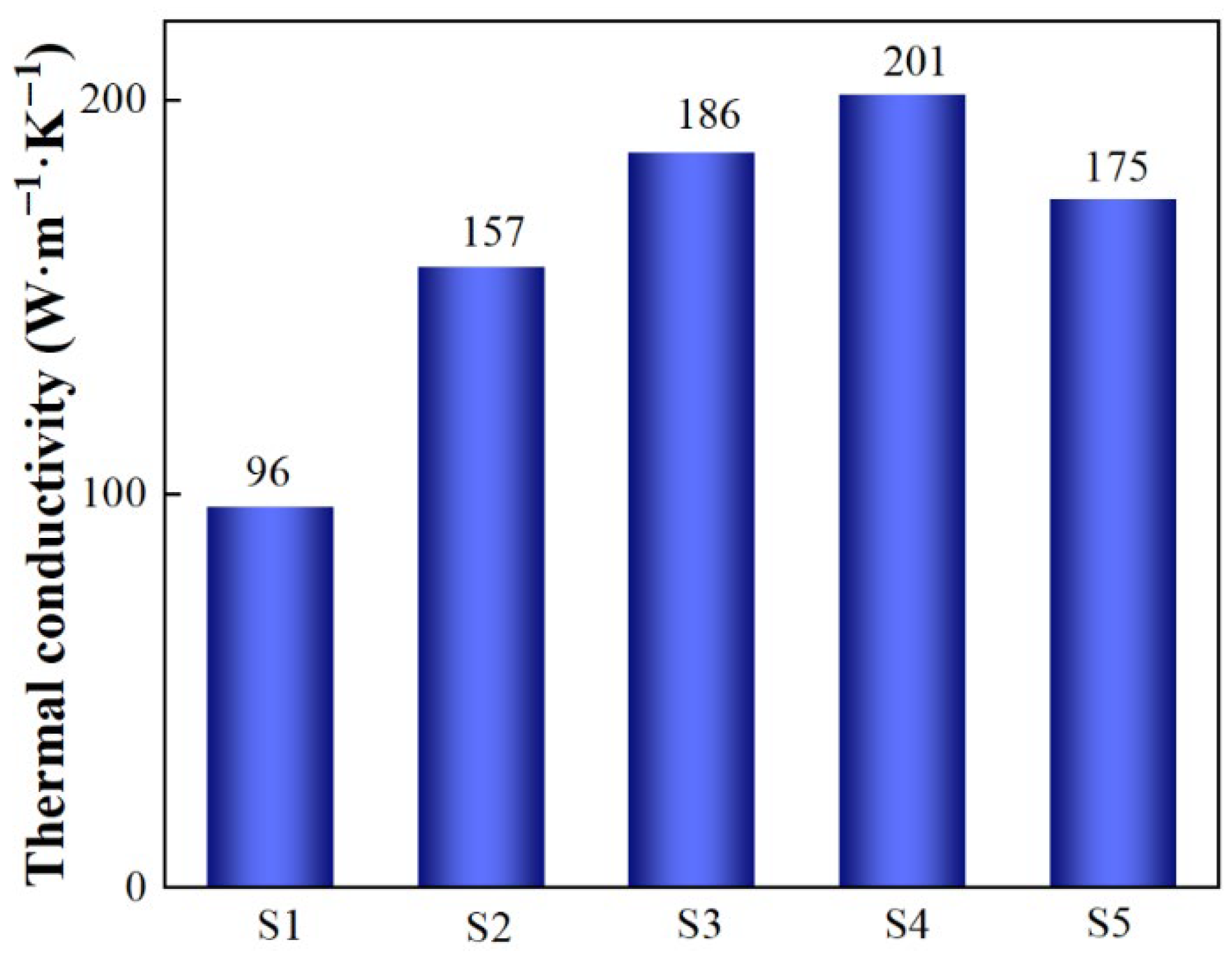

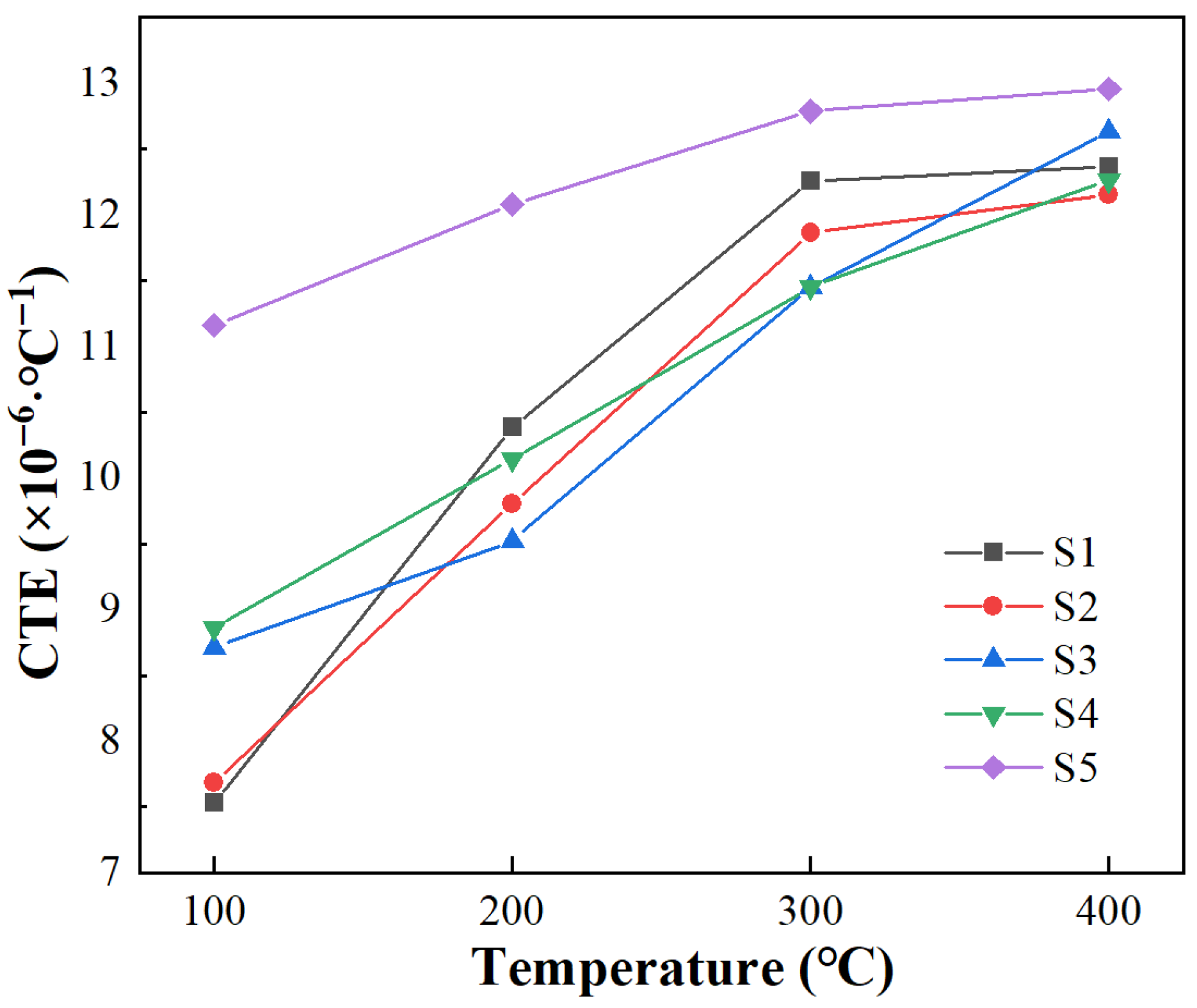

3.4. Thermal Properties of SiCp/Al Composites

4. Conclusions

- (1)

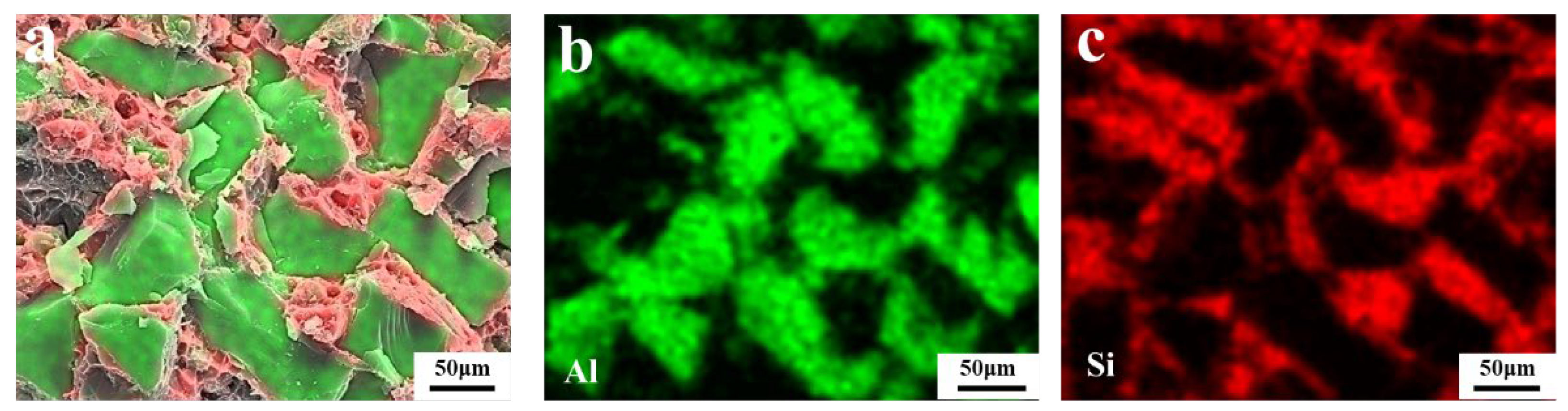

- With an increase in the SiC particle size, the fracture morphologies of the composites gradually transition from intergranular to transgranular. Owing to the presence of SiC particles with varying sizes, both transgranular and intergranular fracture characteristics are observed during particle grading. EDS images demonstrate that SiC and Al are uniformly distributed in the composite, with no Al4C3 formed at the interface and no noticeable porosity observed at the grain boundaries.

- (2)

- The bending strength of the composites increases with increasing SiC particle size, which can be attributed to the combined effects of RD and residual thermal stress. Notably, the particle-graded sample (S5=) exhibits the highest flexural strength because particle grading in SiCp/Al composites enables efficient load transfer under tight stacking conditions, with smaller SiC particles taking on higher loads. Additionally, larger SiC particles mitigate residual stress from thermal mismatch and enhance particle uniformity within the material matrix.

- (3)

- Thermal conductivity increases with a rise in the SiC particle size because larger SiC particles form fewer interfaces than smaller SiC particles, and the existence of an interface significantly reduces thermal conductivity. CTE increases with a rise in SiC particle size because smaller SiC particles have a more restrictive effect on the thermal expansion of Al through the interface.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teng, F.; Yu, K.; Luo, J.; Fang, H.J.; Shi, C.L.; Dai, Y.L.; Xiong, H.Q. Microstructures and properties of Al-50%SiC composites for electronic packaging applications. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2016, 26, 2647−2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.M.; Yu, J.K.; Wang, X.Y. Microstructure and properties of Al/Si/SiC composites for electronic packaging. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2012, 22, 1686−1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.M.; Saravanan, R.A.; Arpón, R.; García-Cordovilla, C.; Louis, E.; Narciso, J. Pressure infiltration of liquid aluminum into packed SiC particulate with a bimodal size distribution. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 247−257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.M.; Narciso, J.; Weber, L.; Mortensen, A.; Louis, E. Thermal conductivity of Al-SiC composites with monomodal and bimodal particle size distribution. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 480, 483−488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, T.M.; Wang, Y.; Baig, M.M.A.B.; Zhou, Z.F.; Hussain, A.; Jamal, S.; Shehzadi, F. Influence of processing routes and SiC volume percentage on microstructure, thermophysical, and mechanical properties of SiCp/Al-6061 composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1041, 183797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Dávila, M.; Pech-Canul, M.A.; Pech-Canul, M.I. Effect of bi-and trimodal size distribution on the superficial hardness of Al/SiCp composites prepared by pressureless infiltration. Powder Technol. 2007, 176, 66−71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.; Jia, C.C.; Tian, W.H.; Liang, X.B.; Chen, H.; Guo, H. Thermal conductivity of spark plasma sintering consolidated SiCp/Al composites containing pores: Numerical study and experimental validation. Compos. A 2010, 41, 161−167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.Y.; Ge, X.L.; Xu, X.J.; Jiang, Z. Influences of SiC Particle Size and Content on the Mechanical Properties and Wear Resistance of the Composites with Al Matrix. Key Eng. Mater. 2008, 375–376, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.L.; Yang, L.X.; Chen, Z.F.; Yang, M.M.; Lu, L. Effects of SiC content on the microstructure and mechanical performance of stereolithography-based SiC ceramics. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 5184–5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, H. The Preparation of High-Volume Fraction SiC/Al Composites with High Thermal Conductivity by Vacuum Pressure Infiltration. Crystals 2021, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Wang, Y.; Ren, L.H.; Li, S.X.; Liu, Y.H.; Jiang, Q.C. Influence of SiC surface polarity on the wettability and reactivity in an Al/SiC system. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 355, 930−938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Li, N.Y.; Li, C.J.; Gao, P.; Guan, H.D.; Yang, C.M.Y.; Pu, C.J.; Yi, J.H. Effects of size and oxidation treatment for SiC particles on the microstructures and mechanical properties of SiCp/Al composites prepared by powder metallurgy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 851, 143664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.Q.; Li, Z.Q.; Fan, G.L.; Kai, X.Z.; Ji, G.; Zhang, L.T.; Zhang, D. Fabrication of diamond/aluminum composites by vacuum hot pressing: Process optimization and thermal properties. Compos. B 2013, 47, 173−180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuuchi, K.; Inoue, K.; Agari, Y.; Nagaoka, T.; Sugioka, M.; Tanaka, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Tani, J.-I.; Kawahara, M.; Makino, Y.; et al. Processing Al/SiC composites in continuous solid-liquid co-existent state by SPS and their thermal properties. Compos. B 2012, 43, 2012−2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.C. Effect of SiC particle content on the mechanical behavior and deformation mechanism of SiCp/Al composite under high-frequency dynamic loading. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 903, 146643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.H. Development Challenge and Opportunity of Metal Matrix Composites. Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2014, 31, 1228−1237. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 6569-2006; Fine Ceramics (Advanced Ceramics, Advanced Technical Ceramics)—Test Method for Flexural Strength of Monolithic Ceramics at Room Temperature. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- GB/T 22588-2008; Test Method for Thermal Diffusivity or Thermal Conductivity by the Flash Method. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Kong, Y.R.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, D. Review on Interfacial Properties of Particles-Reinforced Aluminum Matrix Composites. Mater. Rep. 2015, 29, 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y.Y.; Wu, H.B.; Liu, X.J.; Huang, Z.-R. Grain Composition on Solid-State-Sintered SiC Ceramics. J. Inorg. Mater. 2018, 33, 1167–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, F.; Tong, H.T.; Shen, P.; Cong, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Q. Overview: SiC/Al Interface Reaction and Interface Structure Evolution Mechanism. Acta Metall. Sin. 2019, 55, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Xiao, B. Effects of SiC Particle Size on Tensile Property and Fracture Behavior on Particle Reinforced Aluminum Metal Matrix Composites. Chin. J. Mater. Res. 2009, 23, 211–214. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.W. Effect of Particle Size on Properties of SiCp/Al Composites and Its Numerical Simulation; Harbin Institute of Technology: Harbin, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, B.L.; Bi, J.; Zhao, M.J.; Ma, Z.Y. Effects of SiCp size on tensile property of aluminum matrix composites fabricated by powder metallurgical method. Acta Metall. Sin. 2002, 38, 1006−1008. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.; Peng, C.Q.; Wang, R.C.; Wang, X.F. Research and development of metal matrix composites for electronic packaging. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2015, 15, 3255–3270. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | Particle Sizes of SiC (μm) | Bulk Density (g·cm−3) | Theoretical Density (g·cm−3) | Relative Density (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 5 | 2.65 | 2.93 | 90.4 |

| S2 | 10 | 2.77 | 2.93 | 94.5 |

| S3 | 20 | 2.81 | 2.93 | 95.9 |

| S4 | 50 | 2.92 | 2.93 | 99.7 |

| S5 | 5 + 50 | 2.92 | 2.93 | 99.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Feng, R.; Wu, H.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y.; Pei, B.; Han, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, X.; Huang, Z. Effects of SiC Particle Size on SiCp/Al Composite During Vacuum Hot Pressing. Materials 2026, 19, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010084

Feng R, Wu H, Liu H, Yang Y, Pei B, Han J, Liu Z, Wu X, Huang Z. Effects of SiC Particle Size on SiCp/Al Composite During Vacuum Hot Pressing. Materials. 2026; 19(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010084

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Ruijie, Haibo Wu, Huan Liu, Yitian Yang, Bingbing Pei, Jianshen Han, Zehua Liu, Xishi Wu, and Zhengren Huang. 2026. "Effects of SiC Particle Size on SiCp/Al Composite During Vacuum Hot Pressing" Materials 19, no. 1: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010084

APA StyleFeng, R., Wu, H., Liu, H., Yang, Y., Pei, B., Han, J., Liu, Z., Wu, X., & Huang, Z. (2026). Effects of SiC Particle Size on SiCp/Al Composite During Vacuum Hot Pressing. Materials, 19(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010084