Sustainable Carbon Source from Almond Shell Waste: Synthesis, Characterization, and Electrochemical Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Carbon Material, Bi2O3, Bi2O3-Sm and Preparation of Working Electrode

2.2.1. Synthesis of Bi2O3

2.2.2. Synthesis of Bi2O3-Sm

2.2.3. Synthesis of Carbon Materials

2.2.4. Preparation of CPE Working Electrode

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Lignocellulose Composition of Almond Shells

2.3.2. Nitrogen Physisorption

2.3.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

2.3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Analysis (FTIR)

2.3.5. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopic Analysis (XPS)

2.3.6. Thermogravimetric and Differential Thermal Analysis (TG-DTA)

2.3.7. Electrochemical Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Lingocellulose Composition

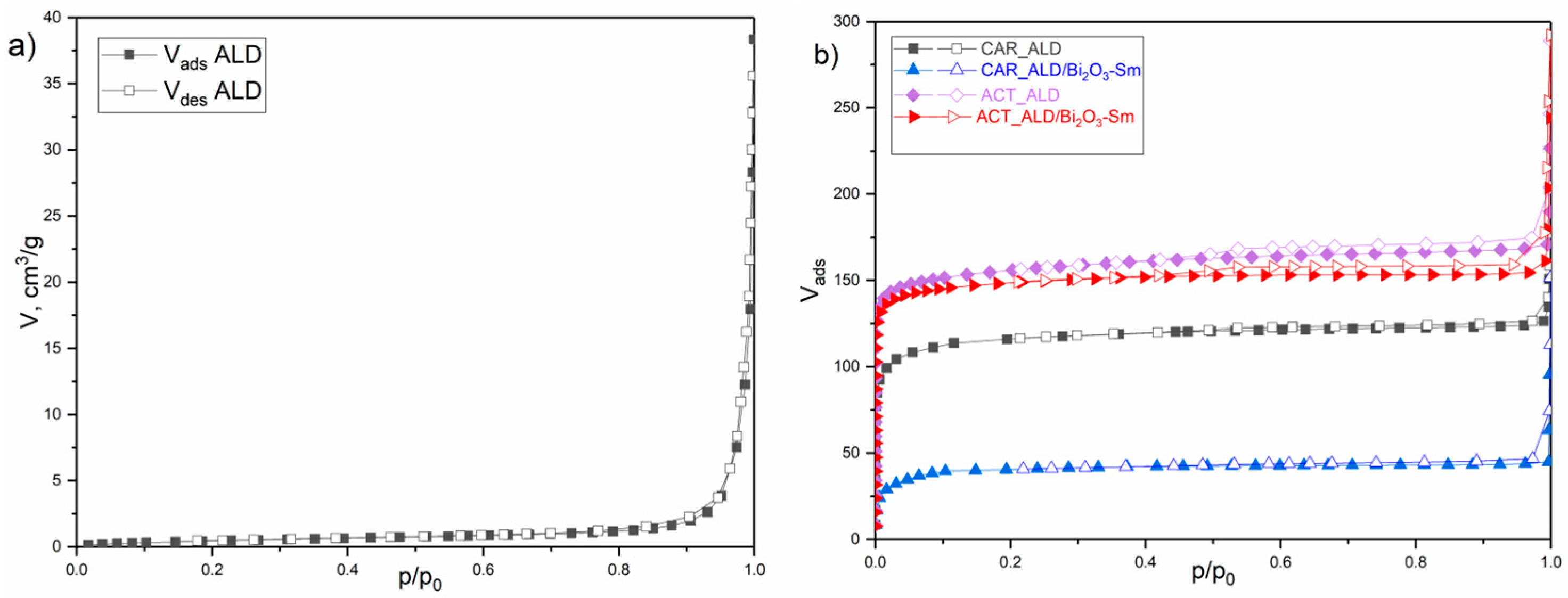

3.2. Nitrogen Physisorption

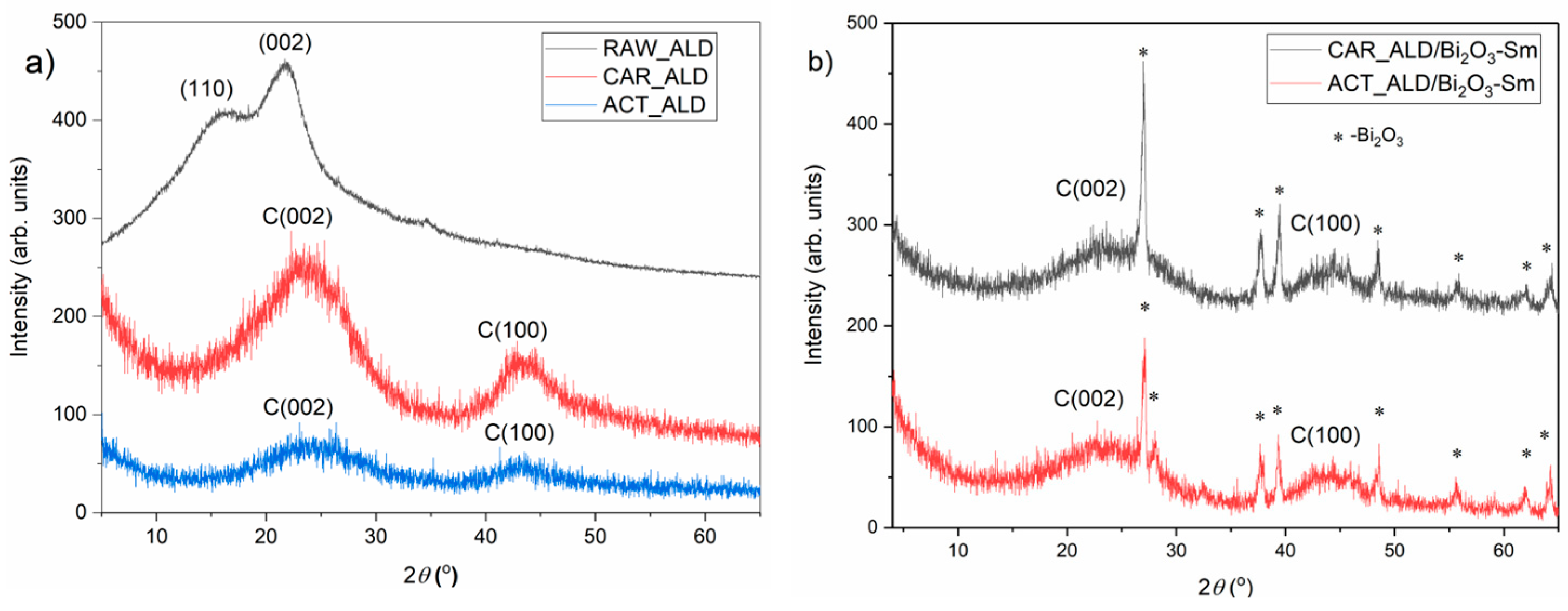

3.3. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Analysis (FTIR)

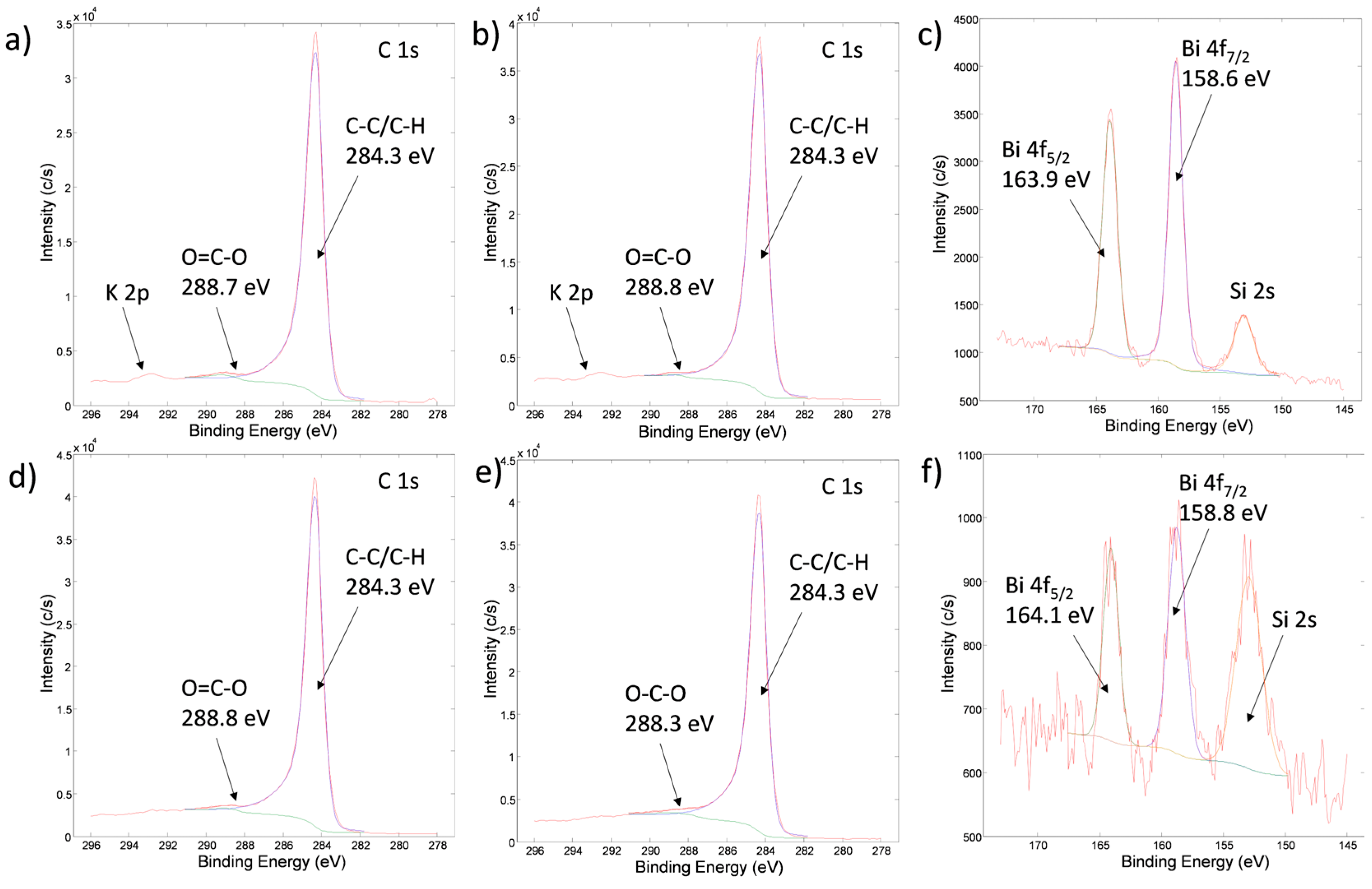

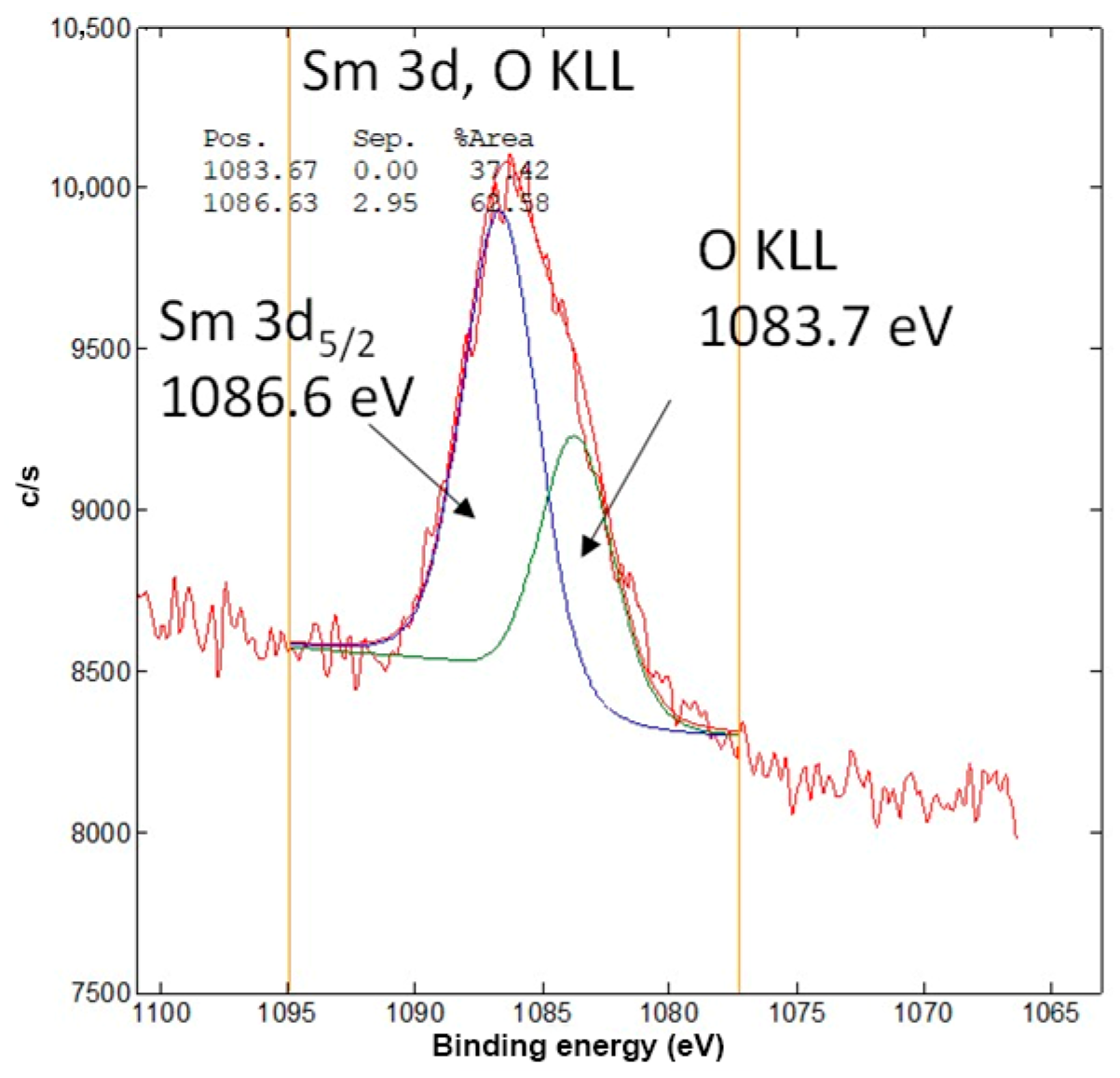

3.5. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopic Analysis (XPS)

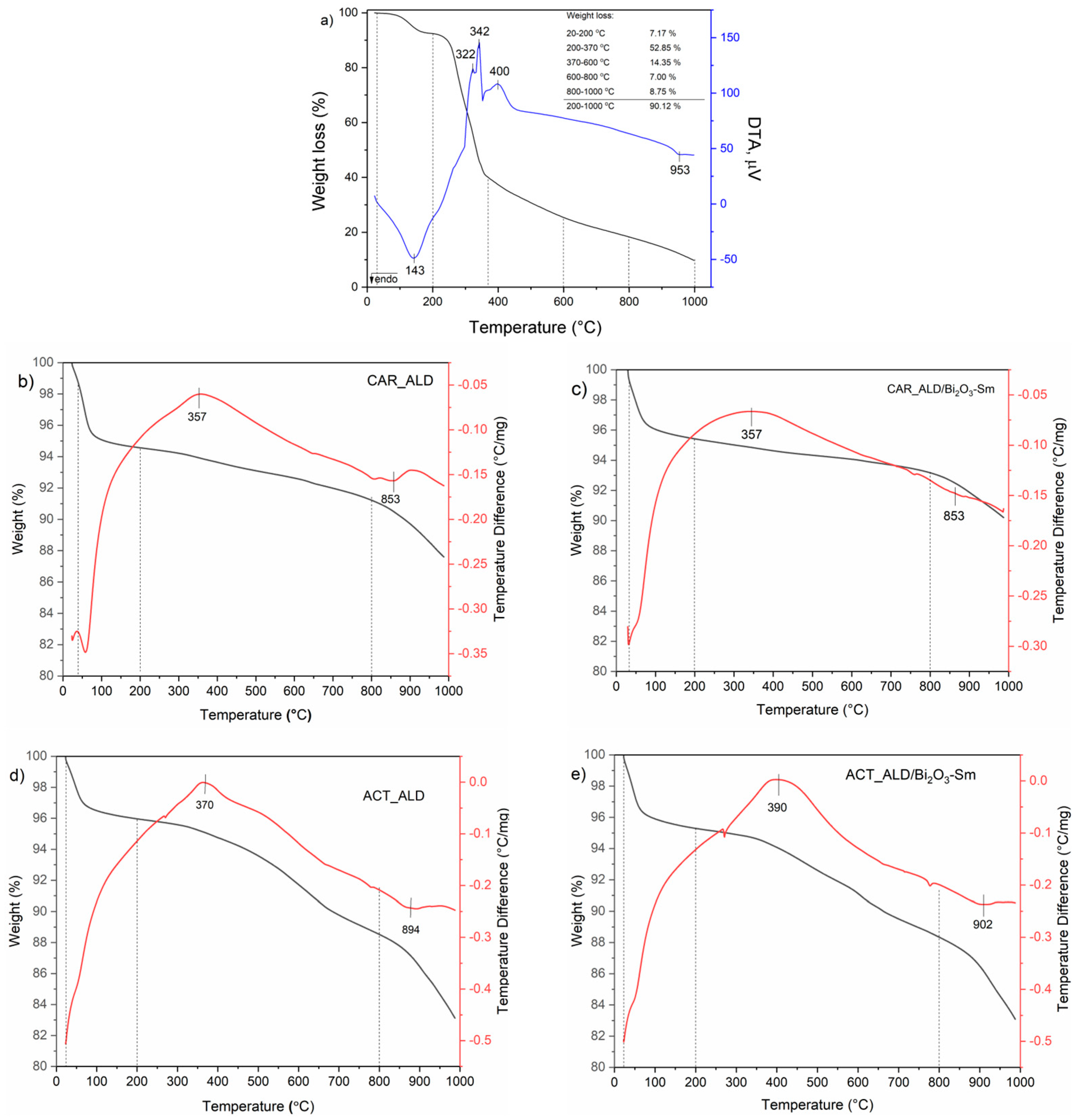

3.6. Thermogravimetric and Differential Thermal Analyses (TGA-DTA)

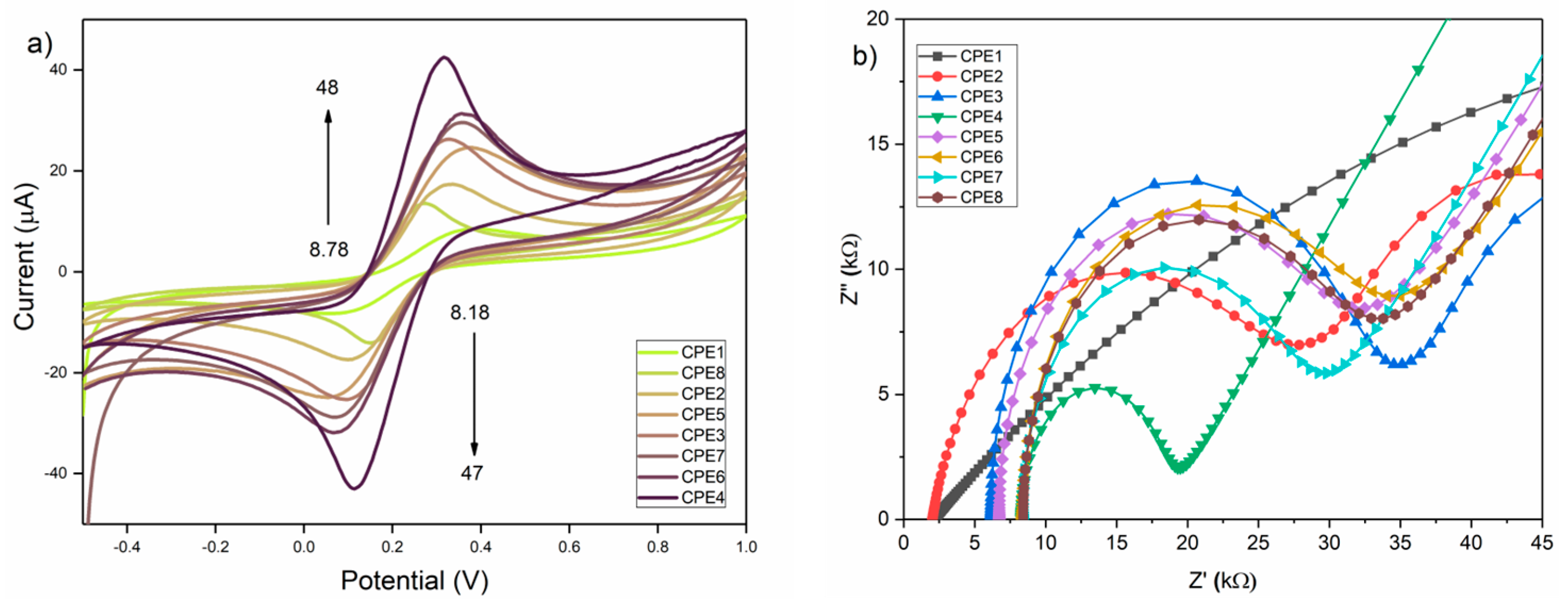

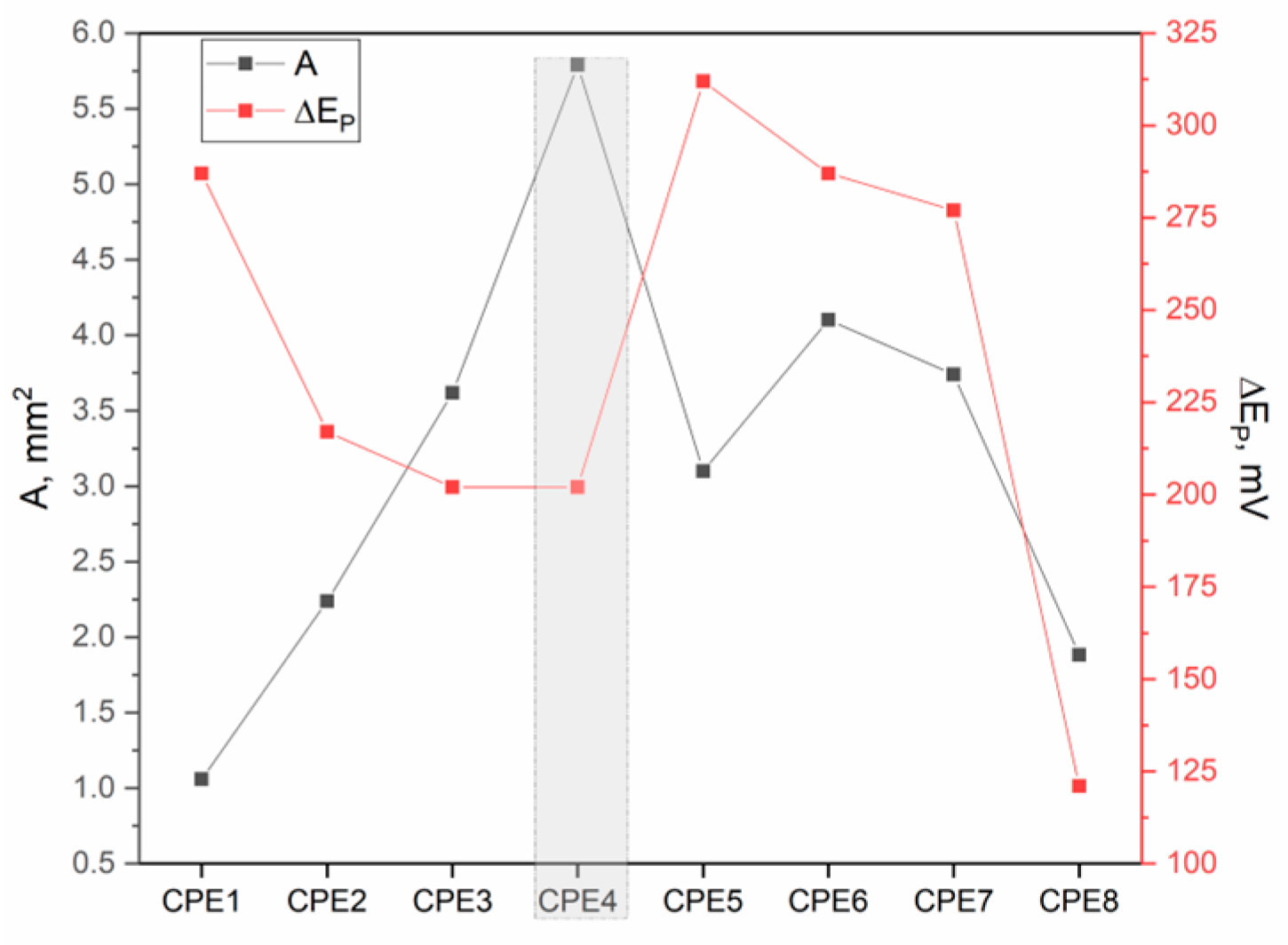

3.7. Electrochemical Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Queirós, C.S.; Cardoso, S.; Lourenço, A.; Ferreira, J.; Miranda, I.; Lourenço, M.J.V.; Pereira, H. Characterization of walnut, almond, and pine nut shells regarding chemical composition and extract composition. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2020, 10, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, M.; Okonkwo, J.O.; Agyei, N.M. Maize tassel-modified carbon paste electrode for voltammetric determination of Cu (II). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 4807–4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, W.; Pawłowska, M. Biomass as Raw Material for the Production of Biofuels and Chemicals, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, D.C.; Pal, A.K.; Nath, D.; Rodriguez-Uribe, A.; Mohanty, A.K.; Pilla, S.; Misra, M. Upcycling of ligno-cellulosic nutshells waste biomass in biodegradable plastic-based biocomposites uses-a comprehensive review. Compos. Part C Open Access 2024, 14, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visco, A.; Scolaro, C.; Facchin, M.; Brahimi, S.; Belhamdi, H.; Gatto, V.; Beghetto, V. Agri-food wastes for bioplastics: European prospective on possible applications in their second life for a circular economy. Polymers 2022, 14, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, R.; Vilya, K.; Pradhan, M.; Nayak, A.K. Recent advancement of biomass-derived porous carbon based materials for energy and environmental remediation applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 6965–7005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akubude, C.V.; Nwaigwe, N.K. Economic Importance of Edible and Non-edible Almond Fruit as Bioenergy Material: A Review. Am. J. Energy Sci. 2016, 3, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fadhil, A.B.; Kareem, B.A. Co-pyrolysis of mixed date pits and olive stones: Identification of bio-oil and the production of activated carbon from bio-char. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 158, 105249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Hao, J.; Wang, W. Study of almond shell characteristics. Materials 2018, 11, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albatrni, H.; Qiblawey, H.; Al-Marri, M.J. Walnut shell based adsorbents: A review study on preparation, mechanism, and application. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 45, 102527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.A.; Dar, B.A. Removal of heavy metal ions (Fe2+, Mn2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+) on to activated carbon prepared from kashmiri walnut shell (Juglans regia). Univers. J. Green Chem. 2024, 2, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazid, H.; Bouzid, T.; El Mouchtari, E.M.; Bahsis, L.; El Himri, M.; Rafqah, S.; El Haddad, M. Insights into the adsorption of Cr (VI) on activated carbon prepared from walnut shells: Combining response surface methodology with computational calculation. Clean Technol. 2024, 6, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farma, R.; Tania, Y.; Apriyani, I. Conversion of hazelnut seed shell biomass into porous activated carbon with KOH and CO2 activation for supercapacitors. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 87, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozpinar, P.; Dogan, C.; Demiral, H.; Morali, U.; Erol, S.; Samdan, C.; Yildiz, D.; Demiral, I. Activated carbons prepared from hazelnut shell waste by phosphoric acid activation for supercapacitor electrode applications and comprehensive electrochemical analysis. Renew. Energy 2022, 189, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez Negro, A.; Martí, V.; Sánchez-Hervás, J.M.; Ortiz, I. Development of Pistachio Shell-Based Bioadsorbents Through Pyrolysis for CO2 Capture and H2S Removal. Molecules 2025, 30, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa, L.A.; Alvarez-Parrilla, E.; Shahidi, F. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of kernels and shells of Mexican pecan (Carya illinoinensis). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kureck, I.; Policarpi, P.D.B.; Toaldo, I.M.; Maciel, M.V.D.O.B.; Bordignon-Luiz, M.T.; Barreto, P.L.M.; Block, J.M. Chemical characterization and release of polyphenols from pecan nut shell [Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh) C. Koch] in zein microparticles for bioactive applications. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2018, 73, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, F.; Agustin-Salazar, S.; Berg, A.L.; Setaro, B.; Micillo, R.; Pizzo, E.; Weber, F.; Gamez-Meza, N.; Schieber, A.; Cerruti, P.; et al. Pecan (Carya illinoinensis (Wagenh.) K. Koch) nut shell as an accessible polyphenol source for active packaging and food colorant stabilization. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 6700–6712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Roque, M.; Del-Toro-Sánchez, C.; Chávez-Ayala, J.; González-Vega, R.; Pérez-Pérez, L.; Sánchez-Chávez, E.; Salas-Salazar, N.; Soto-Parra, J.; Hurralde-García, R.; Flores-Córdova, M. Digestibility, Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Pecan Nutshell. J. Renew. Mater. 2022, 10, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabais, J.M.V.; Laginhas, C.E.C.; Carrott, P.J.M.; Carrott, M.R. Production of activated carbons from almond shell. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraugi, S.S.; Routray, W. Advances in sustainable production and applications of nano-biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 176883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, A.; González-Tejero, M.; Caballero, Á.; Morales, J. Almond shell as a microporous carbon source for sustainable cathodes in lithium–sulfur batteries. Materials 2018, 11, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, Y.; Ji, B.; Cui, B.; Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, M.; Luo, S.; Guo, D. Almond shell-derived, biochar-supported, nano-zero-valent iron composite for aqueous hexavalent chromium removal: Performance and mechanisms. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Yuan, H.; Liu, B.; Peng, J.; Xu, L.; Yang, D. Review of the distribution and detection methods of heavy metals in the environment. Anal. Methods 2020, 12, 5747–5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudiono, T.; Bokov, D.O.; Jasim, S.A.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Khashirbaeva, D.M. State-of-the-art of convenient and low-cost electrochemical sensor for food contamination detection: Technical and analytical overview. Microchem. J. 2022, 179, 107460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletcher, D.; Greff, R.; Peat, R.; Peter, L.M.; Robinson, J. The design of electrochemical experiments. In Instrumental Methods in Electrochemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 356–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik, S.; Beitollahi, H.; Mohammadi, S.Z.; Azimzadeh, M.; Zhang, K.; Van Le, Q.; Yamauchi, Y.; Won Jang, H.; Shokouhimehr, M. Recent developments in electrochemical sensors for detecting hydrazine with different modified electrodes. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 30481–30498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibi, C.; Liu, C.H.; Barton, S.C.; Anandan, S.; Wu, J.J. Carbon materials for electrochemical sensing application—A mini review. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 154, 105071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangaraj, B.; Solomon, P.R.; Ranganathan, S. Synthesis of carbon quantum dots with special reference to biomass as a source—A review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 1455–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluđerović, M.; Savić, S.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Jovanović, A.Z.; Rakočević, L.; Vlahović, F.; Milikić, J.; Stanković, D. Samarium-Doped PbO2 Electrocatalysts for Environmental and Energy Applications: Theoretical Insight into the Mechanisms of Action Underlying Their Carbendazim Degradation and OER Properties. Processes 2025, 13, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijolat, C.; Tournier, G.; Viricelle, J.P. Detection of CO in H2-rich gases with a samarium doped ceria (SDC) sensor for fuel cell applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2009, 141, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutić, T.; Stanković, V.; Milikić, J.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Ortner, A.; Kalcher, K.; Manojlović, D.; Stankovic, D. Sustainable synthesis of samarium molybdate nanoparticles: A simple electrochemical tool for detection of environmental pollutant metol. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2024, 89, 1571–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, A.S.; Ejaz, Y.; Kumar, A.; Dahshan, A. Role of samarium doping in ZnSe electrode material with increased electrocapacitive properties for supercapacitor energy storage applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 172, 113681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Xie, X.; Zhou, S.; Li, W.; Ma, J.; Zhou, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhou, J.; Pan, A. Sm Doping-Enhanced Li3VO4/C Electrode Kinetics for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 3581–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hamdouni, Y.; El Hajjaji, S.; Szabo, T.; Trif, L.; Felhősi, I.; Abbi, K.; Najoua, L.; Harmouche, L.; Shaban, A. Biomass valorization of walnut shell into biochar as a resource for electrochemical simultaneous detection of heavy metal ions in water and soil samples: Preparation, characterization, and applications. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 104252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djemmoe, L.G.; Njanja, E.; Tchieno, F.M.; Ndinteh, D.T.; Ndungu, P.G.; Tonle, I.K. Activated Hordeum vulgare L. dust as carbon paste electrode modifier for the sensitive electrochemical detection of Cd2+, Pb2+ and Hg2+ ions. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2020, 100, 1429–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, B.; Chen, S.; Wu, L.; Yang, J.; Liang, S.; Xiao, K.; Hu, J.; Hou, H. Ultrasensitive and simultaneous electrochemical determination of Pb2+ and Cd2+ based on biomass derived lotus root-like hierarchical porous carbon/bismuth composite. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 087505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajawat, D.S.; Kumar, N.; Satsangee, S.P. Trace determination of cadmium in water using anodic stripping voltammetry at a carbon paste electrode modified with coconut shell powder. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajawat, D.S.; Kardam, A.; Srivastava, S.; Satsangee, S.P. Nanocellulosic fiber-modified carbon paste electrode for ultra trace determination of Cd (II) and Pb (II) in aqueous solution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 3068–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- María-Hormigos, R.; Gismera, M.J.; Sevilla, M.T. Straightforward ultrasound-assisted synthesis of bismuth oxide particles with enhanced performance for electrochemical sensors development. Mater. Lett. 2015, 158, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraz, M.; Naqvi, F.K.; Shakir, M.; Khare, N. Synthesis of samarium-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles with improved photocatalytic performance and recyclability under visible light irradiation. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 2295–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAPPI T 264 cm-97; Preparation of Wood for Chemical Analysis. TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1997.

- Browning, B.L. Methods of Wood Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1967; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- TAPPI T 222 0m-1; Standard Test Method for Acid-Insoluble Lignin in Wood. TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011.

- TAPPI T UM 250; Acid-Soluble Lignin in Wood and Pulp. TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1991.

- ASTM D1110-21; Standard Test Methods for Water Solubility of Wood. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- TAPPI T 413 om-22; Ash in Wood, Pulp, Paper and Paperboard: Combustion at 900 °C. TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022.

- Rouquerol, J.; Rouquerol, F.; Sing, K. Adsorption by Powders and Porous Solids: Principles, Methodology and Applications; Academic Press: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouquerol, J.; Llewellyn, P.; Rouquerol, F.J.S.S.S.C. Is the BET equation applicable to microporous adsorbents? In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 160, pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinin, M.I. Physical adsorption of gases and vapors in micropores. In Progress in Surface and Membrane Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1975; Volume 9, pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, G.; Kawazoe, K. Method for the calculation of effective pore size distribution in molecular sieve carbon. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 1983, 16, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollimore, D.; Heal, G.R. An improved method for the calculation of pore size distribution from adsorption data. J. Appl. Chem. 1964, 14, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulder, J.F.; Chastain, J. RC King in Handbook of X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy: A Reference Book of Standard Spectra for Identification and Interpretation of XPS Data; Physical Electronics: Eden Prairie, MN, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, J.A.; Prieto, M.A.; Ferreira, I.C.; Belgacem, M.N.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Barreiro, M.F. Analysis of the oxypropylation process of a lignocellulosic material, almond shell, using the response surface methodology (RSM). Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 153, 112542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, E.; Arce, C.; Callejón-Ferre, A.J.; Pérez-Falcón, J.M.; Sánchez-Soto, P.J. Thermal behaviour of the different parts of almond shells as waste biomass. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 5023–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Doherty, W.O.S.; Halley, P.J. Developing lignin-based resin coatings and composites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2008, 27, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhao, X.S. Biomass-derived carbon electrode materials for supercapacitors. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2017, 1, 1265–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, W.O.; Mousavioun, P.; Fellows, C.M. Value-adding to cellulosic ethanol: Lignin polymers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 33, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Activated Carbon; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Chapter 5; pp. 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Divya, J.; Shivaramu, N.J.; Roos, W.D.; Purcell, W.; Swart, H.C. Synthesis, surface and photoluminescence properties of Sm3+ doped α-Bi2O3. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 854, 157221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Baker, J.O.; Himmel, M.E.; Parilla, P.A.; Johnson, D.K. Cellulose crystallinity index: Measurement techniques and their impact on interpreting cellulase performance. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2010, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Tripathi, S.K. Almond shell-based activated nanoporous carbon electrode for EDLCs. Ionics 2015, 21, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Manickam, S.; Lester, E.; Wu, T.; Pang, C.H. Synthesis of graphene oxide and graphene quantum dots from miscanthus via ultrasound-assisted mechano-chemical cracking method. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2021, 73, 105519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, B.Z.; Zhou, Z.X. Morphology control and optical properties of Bi2O3 crystals prepared by low-temperature liquid phase method. Micro Nano Lett. 2018, 13, 1443–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; He, Z.; Xie, J.; Li, Y. IR and Raman spectra properties of Bi2O3-ZnO-B2O3-BaO quaternary glass system. Am. J. Anal. Chem. 2014, 5, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.A.; Sinha, S.; Nongthombam, S.; Swain, B.P. Structural, optical, electrochemical and electrical studies of Bi2O3@ rGO nanocomposite. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 137, 106212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuz’micheva, G.; Trigub, A.; Rogachev, A.; Dorokhov, A.; Domoroshchina, E. Physicochemical Characterization and Antimicrobial Properties of Lanthanide Nitrates in Dilute Aqueous Solutions. Molecules 2024, 29, 4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, B.; Udayabhaskar, R.; Kishore, A. Optical and phonon properties of Sm-doped α-Bi2O3 micro rods. Appl. Phys. A 2014, 117, 1409–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaif, N.A.; Alfryyan, N.; Al-Ghamdi, H.; Rammah, Y.S.; Mahdy, E.A.; Abo-Mosallam, H.A.; Talaat, S. Impact of Sm3+ ions on the structure, physical, FTIR spectroscopy and mechano-radiation shielding capabilities of high dense CdO–Bi2O3–SiO2 glasses. Appl. Phys. A 2025, 131, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, H.; Wei, M.; Dong, X.; Gao, L.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J. Effects of Bi2O3, Sm2O3 content on the structure, dielectric properties and dielectric tunability of BaTiO3 ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 19279–19288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkoglu, O.; Altiparmak, F.; Belenli, I. Stabilization of Bi2O3 Polymorphs with Sm2O3 Doping. Chem. Pap.—Slovac Acad. Sci. 2003, 57, 304–308. [Google Scholar]

- Debevc, S.; Weldekidan, H.; Snowdon, M.R.; Vivekanandhan, S.; Wood, D.F.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Valorization of almond shell biomass to biocarbon materials: Influence of pyrolysis temperature on their physicochemical properties and electrical conductivity. Carbon Trends 2022, 9, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurnansyah, Z.; Jayanti, P.D.; Mahardhika, L.J.; Kusumah, H.P.; Istiqomah, N.I.; Suharyadi, E. Microstructural and optical properties of green-synthesized rGO utilizing Amaranthus viridis extract. Mater. Sci. Forum 2024, 1113, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafizadeh, F. Pyrolysis and combustion of cellulosic materials. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. 1968, 23, 419–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhyani, V.; Bhaskar, T. Pyrolysis of biomass. In Biofuels: Alternative Feedstocks and Conversion Processes for the Production of Liquid and Gaseous Biofuels; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 217–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, S.D.; Kalogiannis, K.G.; Iliopoulou, E.F.; Michailof, C.M.; Pilavachi, P.A.; Lappas, A.A. A study of lignocellulosic biomass pyrolysis via the pyrolysis of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2014, 105, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Powdered Graphite for Lithium-Ion Batteries, TA Instruments. (n.d.). Thermal Analysis Application Note: 67. TA470. TA Instruments. Available online: https://www.tainstruments.com/pdf/literature/TA470.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Oliveira, G.F.D.; Andrade, R.C.D.; Trindade, M.A.G.; Andrade, H.M.C.; Carvalho, C.T.D. Thermogravimetric and spectroscopic study (TG–DTA/FT–IR) of activated carbon from the renewable biomass source babassu. Química Nova 2017, 40, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ognjanović, M.; Marković, M.; Girman, V.; Nikolić, V.; Vranješ-Đurić, S.; Stanković, D.M.; Petković, B.B. Metal–Organic Framework-Derived CeO2/Gold Nanospheres in a Highly Sensitive Electrochemical Sensor for Uric Acid Quantification in Milk. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andjelković, L.; Đurđić, S.; Stanković, D.; Kremenović, A.; Pavlović, V.B.; Jeremić, D.A.; Šuljagić, M. Electrochemical detection of acetaminophen in pharmaceuticals using rod-shaped α-Bi2O3 prepared via reverse co-precipitation. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.G.; Marra, M.C.; Silva, I.C.; Siqueira, G.P.; Crapnell, R.D.; Banks, C.E.; Richter, M.E.; Muñoz, R.A. Sustainable 3D-printing from coconut waste: Conductive PLA-biochar filaments for environmental electrochemical sensing. Microchim. Acta 2025, 192, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knežević, S.; Ognjanović, M.; Dojčinović, B.; Antić, B.; Vranješ-Đurić, S.; Manojlović, D.; Stanković, D.M. Sensing platform based on carbon paste electrode modified with bismuth oxide nanoparticles and SWCNT for submicromolar quantification of honokiol. Food Anal. Methods 2022, 15, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mass | CAR_ALD | CAR_ALD/Bi2O3-Sm | ACT_ALD | ACT_ALD/Bi2O3-Sm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m0 (g) | 42.16 | 42.85 | 11.00 | 8.01 |

| mf (g) | 11.82 | 13.40 | 9.82 | 6.24 |

| ω (%) | 28.03 | 31.27 | 89.27 | 77.90 |

| Mass% | CAR_ALD | CAR_ALD/Bi2O3-Sm | ACT_ALD | ACT_ALD/Bi2O3-Sm | Modifiers | Paraffine Oil | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi2O3 | Bi2O3-Sm | ||||||

| CPE1 | 80 | 20 | |||||

| CPE2 | 66.6 | 13.4 | 20 | ||||

| CPE3 | 66.6 | 13.4 | 20 | ||||

| CPE4 | 80 | 20 | |||||

| CPE5 | 80 | 20 | |||||

| CPE6 | 66.6 | 13.4 | 20 | ||||

| CPE7 | 66.6 | 13.4 | 20 | ||||

| CPE8 | 80 | 20 | |||||

| Cellulose, % | Hemicelluloses, % | Lignin, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAW_ALD [this study] | 34.25 | 13.48 | 48.09 |

| Almond shell [54] | 34.39 | 13.96 | 39.92 |

| Almond shell [9] | 38.47 | 28.82 | 29.54 |

| RAW_ALD | CAR_ALD | CAR_ALD/Bi2O3-Sm | ACT_ALD | ACT_ALD/Bi2O3-Sm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSABET, m2g−1 | 2 | 451 | 163 | 535 | 528 |

| CBET | 15 | 1240 | 159 | 58,270 | 42,790 |

| Vtot, cm3g−1 | 0.015 | 0.194 | 0.069 | 0.262 | 0.244 |

| Vmes-DH, cm3g−1 | - | 0.022 | 0.009 | 0.034 | 0.018 |

| Vmic-DR, cm3g−1 | - | 0.181 | 0.067 | 0.236 | 0.229 |

| Vmic-HK, cm3g−1 | - | 0.176 | 0.062 | 0.239 | 0.229 |

| Dmax-HK, nm | - | 0.53 | 1.09 | 0.46 | 0.49 |

| Electrode | Ia (µA) | Ic (µA) | Ia/Ic | ∆Ep (mV) | Rct (kΩ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPE1 | 8.78 ± 0.31 | −8.18 ± 0.29 | 1.07 | 287 | / |

| CPE2 | 18.60 ± 0.65 | −17.60 ± 0.62 | 1.05 | 217 | 25.61 ± 0.90 |

| CPE3 | 30.00 ± 1.05 | −26.00 ± 0.91 | 1.15 | 202 | 28.67 ± 1.00 |

| CPE4 | 48.00 ± 1.68 | −47.00 ± 1.64 | 1.02 | 202 | 11.18 ± 0.39 |

| CPE5 | 25.70 ± 0.90 | −24.45 ± 0.85 | 1.05 | 312 | 25.31 ± 0.88 |

| CPE6 | 34.00 ± 1.19 | −33.00 ± 1.15 | 1.03 | 287 | 26.30 ± 0.92 |

| CPE7 | 31.00 ± 1.08 | −30.00 ± 1.05 | 1.03 | 277 | 21.09 ± 0.74 |

| CPE8 | 15.62 ± 0.55 | −14.55 ± 0.51 | 1.07 | 121 | 25.02 ± 0.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nikolić, K.; Kragović, M.; Stojmenović, M.; Popović, J.; Krstić, J.; Kovač, J.; Gulicovski, J. Sustainable Carbon Source from Almond Shell Waste: Synthesis, Characterization, and Electrochemical Properties. Materials 2026, 19, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010008

Nikolić K, Kragović M, Stojmenović M, Popović J, Krstić J, Kovač J, Gulicovski J. Sustainable Carbon Source from Almond Shell Waste: Synthesis, Characterization, and Electrochemical Properties. Materials. 2026; 19(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleNikolić, Katarina, Milan Kragović, Marija Stojmenović, Jasmina Popović, Jugoslav Krstić, Janez Kovač, and Jelena Gulicovski. 2026. "Sustainable Carbon Source from Almond Shell Waste: Synthesis, Characterization, and Electrochemical Properties" Materials 19, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010008

APA StyleNikolić, K., Kragović, M., Stojmenović, M., Popović, J., Krstić, J., Kovač, J., & Gulicovski, J. (2026). Sustainable Carbon Source from Almond Shell Waste: Synthesis, Characterization, and Electrochemical Properties. Materials, 19(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010008