1. Introduction

Aluminum alloys are extensively utilized in both research and development and industrial applications due to their low density, affordability, high ductility, and excellent corrosion resistance. Advancements in the industrial and technological sectors have resulted in increased demand for aluminium-based materials, which must exhibit enhanced physical, mechanical, tribological, thermal and corrosion properties to meet these demands. In comparison with aluminium alloys, aluminium matrix composites (AMCs) offer superior strength, creep resistance, wear resistance, corrosion resistance, and a lower coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) [

1,

2]. It is evident that these materials demonstrate broad application potential in a variety of sectors, including aerospace [

3] and automotive [

4]. This is particularly relevant in the current trend towards automotive lightweighting, where these materials can effectively reduce component weight and enhance fuel economy [

5,

6].

However, traditional ceramic particle-reinforced aluminium matrix composites (e.g., SiC or Al

2O

3 reinforcements) exhibit significant degradation of mechanical properties under high-temperature conditions and insufficient bonding strength at the interface between the reinforcement and matrix, limiting their further application [

7,

8,

9]. For instance, uncontrolled interfacial reactions at elevated temperatures readily lead to crack initiation, reducing the material’s service life. Consequently, the development of novel reinforcements to overcome these performance bottlenecks has become a major area of research in materials science [

10,

11].

In addition, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have attracted significant interest in this domain. Yan et al. successfully prepared a CNT-reinforced A356 aluminium alloy casting nanocomposite using a molten metal route [

12]. Zhou et al. fabricated a CNT-reinforced aluminium composite material via a pressureless infiltration process [

13]. However, it has been demonstrated that CNTs are unable to withstand elevated temperatures and are susceptible to oxidation at 500 °C [

14]. Furthermore, they have been observed to react readily at interfaces to form products (Al

4C

3), resulting in reduced wettability and affinity [

15].

In contrast, boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) offer a superior combination of high tensile strength, large elastic modulus, exceptional thermal stability (stable up to ~900 °C in air), and strong resistance to oxidation. BNNTs share a structural resemblance to CNTs but possess a wide band gap (~5.5 eV), excellent chemical inertness, and higher flexibility, making them highly suitable for metal-matrix reinforcement in extreme-environment applications [

16]. Recent reviews, such as Turhan et al. (2022), highlight BNNTs’ outstanding mechanical, thermal, and dielectric properties, as well as their growing potential in multifunctional composite systems [

17].

In addition to BN-based nanostructures, aluminum nitride (AlN) nanotubes represent another important class of III–V nitride nanomaterials that exhibit high thermal conductivity, good electrical insulation, and strong covalent bonding. Their structural and electronic characteristics make AlN nanotubes relevant to metal-matrix composites and interfacial reaction studies. Moreover, the presence of defects, such as vacancies or color centers (F-centers), in BN and AlN nanotubes can significantly alter their electronic structure, chemical reactivity, and interaction with metal matrices [

18]. Zhukovskii et al. (2007) reported that F-centers in AlN nanotubes induce notable variations in electronic states and bonding behavior [

19], which directly influence interfacial characteristics and stabilization mechanisms in composite systems. These defect-related effects are particularly important for understanding interfacial reactions and bonding with aluminum melts.

Despite these advantages, the interfacial bonding mechanism between BNNTs and aluminum remains insufficiently understood. Current studies have not systematically clarified how BNNTs disperse, react, or form interfacial phases (such as AlN or AlB2) under high-temperature casting conditions. Additionally, the roles of structural defects in BNNTs and related nitride nanotubes—particularly their influence on interfacial reactivity, wettability, and phase evolution—have not been comprehensively addressed. This lack of fundamental understanding limits the optimization of processing parameters and hinders the development of BNNT-reinforced aluminum composites with stable performance.

Moreover, while BNNTs/Al composites have shown great potential in mechanical and thermal enhancement, their application in specific engineering components, such as automotive connecting rods, remains largely unexplored. Existing studies rarely extend beyond material synthesis and characterization to industrial-level component fabrication, performance validation, and practical engineering evaluation.

To address these challenges, the present study conducts an in-depth investigation into the interfacial bonding mechanism between BNNTs and the Al matrix. A systematic analysis of the interfacial characteristics of BNNTs/Al composites was conducted, thereby revealing the intrinsic relationship between interfacial bonding strength and preparation process parameters, thus elucidating the bonding mechanism. Concurrently, the preparation process for BNNTs/Al composites is being optimized. The fabrication of BNNTs/Al composite connecting rods is achieved through the implementation of a stirred casting method. The optimisation of process parameters is pivotal in ensuring the uniform dispersion of BNNTs within the Al matrix, thereby facilitating strong interfacial bonding. This, in turn, enhances the mechanical properties and operational reliability of the composite material. A comparative analysis is conducted with traditional 40Cr steel. The proposed BNNTs/Al composite connecting rod manufacturing process demonstrates promising potential for industrial translation, based on the use of conventional powder metallurgy routes and standard automotive component geometries.

4. Application of BNNTs/Al on Automotive Connecting Rods

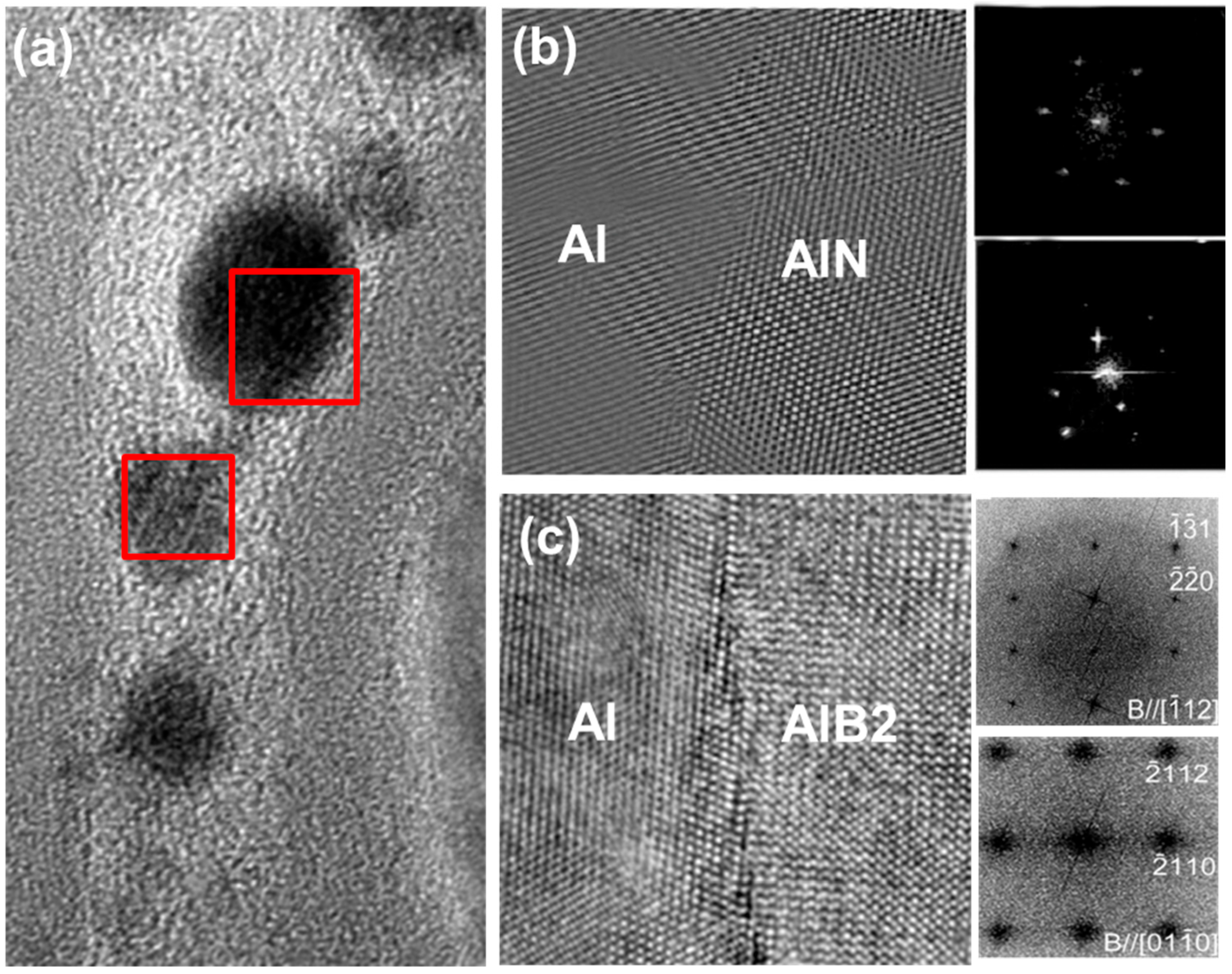

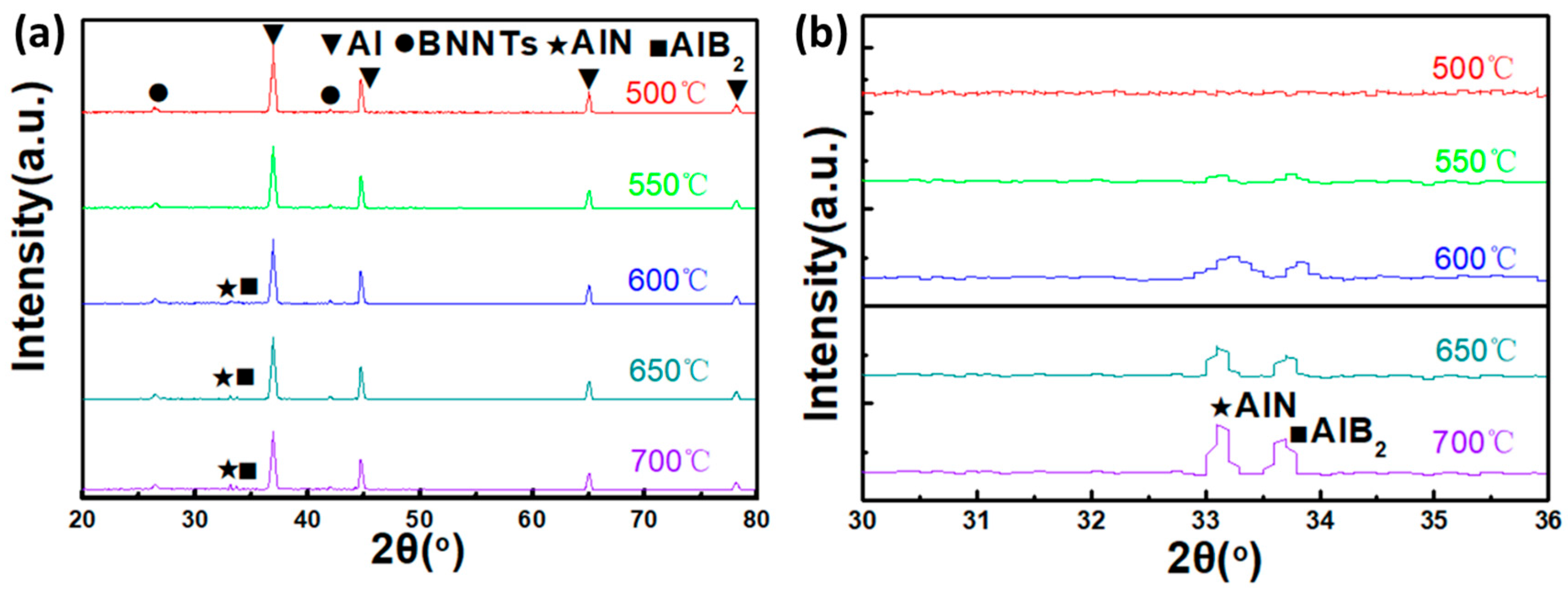

BNNTs/Al composites have been demonstrated to have broad application prospects in the lightweight design and manufacturing of automotive connecting rods. This is due to their outstanding mechanical properties, thermal conductivity and vibration damping capabilities. The present study aims to evaluate the microstructure and mechanical properties of BNNTs/Al composite connecting rods. In order to achieve this objective, the study systematically characterises different regions of the connecting rod using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and mechanical testing. The focal point of this study pertained to the dispersion state of BNNTs within the Al matrix, the interface bonding conditions, and their impact on connecting rod performance. The results indicate that an optimized stirred casting process can produce BNNTs/Al composite connecting rods with uniform microstructure and excellent mechanical properties, laying a solid foundation for their widespread application in the automotive industry. As illustrated in

Figure 7, the microstructural morphology of the BNNTs/Al composite connecting rod varies according to the location. A preliminary investigation into the matrix structure of the three representative regions (big end, small end, and web) was conducted using low-magnification SEM images. As indicated by the arrows in

Figure 7, the BNNTs appear as fine fibrous features uniformly embedded in the aluminum matrix at all examined locations. The results indicate that the matrix structure is uniformly dense, with no apparent casting defects such as shrinkage porosity or shrinkage cavities. This finding suggests that the stirred casting process effectively regulates the solidification process and suppresses defect formation. It can be observed that BNNTs are uniformly dispersed throughout the Al matrix in all three regions—big end, small end, and web—with no significant agglomeration or precipitation phenomena. This uniformity is attributed to the shear forces and turbulent effects during the stirred casting process, which ensure thorough dispersion and mixing of BNNTs within the Al melt [

34]. Moreover, no significant interfacial voids or debonding were observed between BNNTs and the Al matrix, indicating excellent interfacial bonding between the two.

The mechanical properties of the material in automotive connecting rod applications were the focus of a study that simultaneously evaluated and compared them with those of conventional 40Cr steel. As illustrated in

Figure 8, a comparison is presented of performance test results under compressive loading for the BNNTs/Al composite and 40Cr steel. As demonstrated in

Figure 8a, the compressive strength of 40Cr steel is considerably higher than that of the BNNTs/Al composite. The compressive yield strength of 40Cr steel is approximately 717 MPa, while that of the BNNTs/Al composite is about 385 MPa, with the former being approximately 1.86 times that of the latter. This is primarily due to the quenching and tempering treatment of 40Cr steel, which results in the formation of a mixed microstructure comprising martensite and bainite. This process leads to the development of high strength and hardness [

35]. Despite the presence of high-strength BNNTs within the BNNTs/Al composite, the matrix of the composite consists of a soft aluminium alloy, thereby resulting in an overall strength level that is comparatively low. However, the shape of the compression deformation curve indicates that the BNNTs/Al composite exhibits superior plastic deformation capability. Upon attaining its yield strength, the BNNTs/Al composite exhibits a capacity to withstand substantial compressive strain without a discernible decline in stress, thereby demonstrating remarkable strain hardening effects and ductility. Conversely, 40Cr steel demonstrates a swift decline in stress with rising strain post-yield strength, signifying comparatively diminished plastic deformation capacity and heightened vulnerability to brittle fracture.

Figure 8a also presents the elongation data of both materials under compressive loading. The compressive elongation of the BNNTs/Al composite was found to be approximately 29.4%, which is significantly higher than the 11.2% observed for 40Cr steel. This finding suggests that the BNNTs/Al composite possesses an enhanced resistance to compressive deformation without fracture, demonstrating superior plasticity and toughness. The primary factor contributing to this performance is the exceptional mechanical properties of BNNTs, which exhibit a high interfacial bonding strength. BNNTs are uniformly dispersed within the aluminium matrix, forming a dense nanoscale network structure that effectively hinders dislocation movement and propagation. This, in turn, enhances the composite’s strength and toughness [

36,

37]. A robust interfacial bond between BNNTs and the aluminium matrix efficiently transfers loads and mitigates stress concentration, improving the composite’s deformation capacity and fracture toughness. Beyond compressive strength and elongation, material density exerts a substantial influence on the practical applications of the material. The density of 40Cr steel is approximately 7.85 g/cm

3, while the BNNTs/Al composite measures about 2.7 g/cm

3—the former being roughly 2.9 times denser than the latter. This indicates that for equivalent volumes, the density of 40Cr steel (7.85 g/cm

3) is approximately 2.9 times that of the BNNTs/Al composite (2.7 g/cm

3). Consequently, when assessing a material’s mechanical properties, it is imperative to introduce the concept of specific strength, defined as the ratio of a material’s strength to its density.

Figure 8b presents a comparison of the compressive strength-to-density ratio for BNNTs/Al composites and 40Cr steel. The compressive strength-to-density ratio of 40Cr steel is approximately 91.3 MPa·cm

3/g, while that of BNNTs/Al composites is about 142.6 MPa·cm

3/g, representing approximately 1.56 times that of the former. This finding suggests that, despite the composite’s lower absolute strength compared to 40Cr steel, its specific strength performance exceeds that of 40Cr steel when density is taken into account. This advantage is primarily attributable to the superior specific stiffness and specific strength of the BNNTs/Al composite. BNNTs possess inherently elevated strength and modulus, while maintaining a density comparable to carbon nanotubes. When dispersed uniformly in the aluminium matrix at a low volume fraction, BNNTs have been shown to significantly enhance the composite’s mechanical properties while preserving low density. This property endows BNNTs/Al composites with a distinct advantage in specific strength.

The tensile properties of the material in automotive connecting rod applications were the subject of further evaluation and comparison with conventional 40Cr steel. As illustrated in

Figure 9, a comparison is presented of performance test results under tensile loading for the BNNTs/Al composite and 40Cr steel. As demonstrated in

Figure 9a, the tensile strength of 40Cr steel is considerably higher than that of the BNNTs/Al composite, as evidenced by the tensile performance curve. The tensile yield strength of 40Cr steel is approximately 590 MPa, while that of the BNNTs/Al composite is about 212 MPa, with the former being approximately 1.36 times that of the latter. The fundamental reason for this discrepancy is attributable to the intrinsic composition and structural characteristics of the materials. Following quenching and tempering, 40Cr steel develops a composite microstructure of tempered martensite and carbides, thereby acquiring high strength and hardness. Despite the presence of high-strength BNNTs within the BNNTs/Al composite, the matrix of the composite is a soft aluminium alloy, thereby resulting in an overall strength level that is comparatively low. Despite the BNNTs/Al composite’s lower tensile strength in comparison to 40Cr steel, the shape of its tensile deformation curve indicates that it exhibits plastic deformation capabilities that are comparable to those of 40Cr steel. The tensile elongation data for both materials is comparable, with 40Cr steel exhibiting an approximate value of 11.2% and BNNTs/Al composites demonstrating a similar figure of around 11.4%. This finding suggests that BNNTs/Al composites possess the capacity to undergo substantial plastic deformation under tensile loading conditions without succumbing to premature fracture, thereby demonstrating exceptional ductility and toughness. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the uniform dispersion of BNNTs within the aluminium matrix and their effective load transfer function. A robust interfacial bond is formed between BNNTs and the aluminium matrix, which effectively suppresses dislocation movement and impedes crack propagation, thereby enhancing the composite’s plastic toughness [

38]. In addition to strength and ductility, the elastic modulus is an important parameter reflecting the stiffness of structural materials. The elastic modulus was experimentally determined from the initial linear region (strain < 0.2%) of the tensile stress–strain curves by linear fitting. The Young’s modulus of the BNNTs/Al composite is approximately 70 GPa (E = 105/0.0015 = 70 GPa), whereas that of 40Cr steel is about 213 GPa (E = 320/0.0015 = 213 GPa). This difference is mainly attributed to the intrinsic modulus of the aluminum matrix compared with steel.

In addition to tensile strength and elongation, the specific strength of a material is a crucial indicator of its lightweight performance.

Figure 9b presents a comparison of the tensile specific strength of BNNTs/Al composites and 40Cr steel. The material under consideration has a density of approximately 7.85 g/cm

3 and a tensile yield strength of about 590 MPa. This results in a tensile specific strength of approximately 75.2 MPa·cm

3/g. The BNNTs/Al composite has a density of approximately 2.7 g/cm

3 and a tensile yield strength of about 212 MPa, resulting in a tensile specific strength of approximately 78.5 MPa·cm

3/g. It has been demonstrated that, despite the composite’s lower absolute strength compared to 40Cr steel, its specific strength performance is marginally superior when density is considered. This finding suggests that the BNNTs/Al composite exhibits both high tensile strength and reduced material density, thereby demonstrating considerable potential for lightweighting applications.

In addition, a comparison

Table 1 summarizing density, yield strength, elongation, and specific strength has been added to provide a clearer overview of the mechanical performance of the two materials.

In order to comprehensively evaluate the potential of BNNTs/Al composites in automotive connecting rod applications, this study selected conventional 40Cr steel as the reference material. As illustrated in

Figure 10a, the surface morphology of a 40Cr steel connecting rod features mature production processes and reliable performance, thus making it a widely adopted component in the automotive industry. However, the high density of 40Cr steel (7.85 g/cm

3) poses challenges in the context of the prevailing trend of automotive lightweighting. BNNTs/Al composites, with their low density (2.7 g/cm

3) and excellent specific strength, hold considerable promise as a novel connecting rod material to replace 40Cr steel. As illustrated in

Figure 10b, the physical specimen of the BNNTs/Al composite connecting rod, innovatively fabricated in this study, is presented. It was possible to successfully obtain a composite connecting rod with good surface quality and high dimensional accuracy by means of optimized stir casting and precision forming processes. This outcome unequivocally substantiates the immense potential of BNNTs/Al composites in the fabrication of intricate components. In order to more accurately simulate real automotive operating conditions, a 40Cr steel connecting rod dismantled from a Toyota Carina engine was selected as a reference, as illustrated in

Figure 10c. The characterisation of the morphology and properties of the connecting rod under actual service conditions provides a crucial reference point for the design and preparation of composite connecting rods. Concurrently, the effects of material substitution were visually demonstrated by substituting the connecting rod material—replacing the 40Cr steel connecting rod with a BNNTs/Al composite connecting rod (

Figure 10d)—laying the foundation for subsequent performance evaluations.

The automotive performance of BNNTs/Al composite connecting rods, including braking force and fuel consumption characteristics, was evaluated using controlled bench-scale tests. Detailed descriptions of the test setup, measurement procedures, repetition protocol, and data processing methods are provided in the

Supplementary Materials (Text S4).

The braking performance of a vehicle has a direct impact on driving safety and serves as a key indicator for evaluating the reliability of its powertrain system. As a core component in the transmission of engine power, the material and structure of connecting rods have been demonstrated to have a significant influence on braking performance [

39]. This study investigates the impact of material lightweighting on automotive braking performance by comparing the braking force of 40Cr steel connecting rods and BNNTs/Al composite connecting rods under different operating conditions. As illustrated in

Figure 11a, the braking force variation curves for both connecting rods are presented within the 500–1300 rpm speed range. In general, the BNNTs/Al connecting rod displays a reduced braking force in comparison to its 40Cr steel counterpart, thus indicating an enhanced braking performance. At 1300 rpm, for instance, the 40Cr steel connecting rod generates 428 N of braking force, while the BNNTs/Al connecting rod produces only 400 N—a 6.5% reduction. This disparity is primarily attributable to the smaller moment of inertia and rotational resistance exhibited by the BNNTs/Al connecting rod. On the one hand, the density of BNNTs/Al (2.7 g/cm

3) is significantly lower than that of 40Cr steel (7.85 g/cm

3). It has been demonstrated that, at identical dimensions, the lighter mass results in a smaller moment of inertia, thereby facilitating rapid braking. Conversely, the BNNTs/Al composite demonstrates superior specific strength and specific stiffness in comparison to 40Cr steel. When subjected to equivalent loads, the material exhibits reduced deformation and maintains greater stability in the clearance between moving pairs, thereby decreasing rotational resistance. Furthermore, as demonstrated in

Figure 11a, the braking force of the connecting rod increases gradually with rising rotational speed, with the increase being less pronounced for the BNNTs/Al connecting rod compared to the 40Cr steel counterpart. This is primarily due to the fact that higher rotational speeds result in greater inertial forces on the connecting rod, which consequently exerts stronger impacts on the braking system. The BNNTs/Al linkage has been demonstrated to be effective in attenuating high-frequency vibrations, thereby ensuring stable braking force output. This effect is attributed to the linkage’s superior vibration damping properties. The exceptional strength, rigidity, and damping properties of BNNTs/Al composite materials effectively mitigate impact loads during emergency braking, enhance braking efficiency, and establish a material foundation for ensuring vehicle and occupant safety.

Fuel economy is a pivotal metric in evaluating the efficiency of automotive powertrains. In the context of dwindling fuel reserves, the enhancement of engine efficiency and the reduction of fuel consumption are of paramount importance for the conservation of resources and the protection of the environment. As a moving component within the engine, the weight and inertial forces of connecting rods directly impact fuel consumption. This section draws parallels between the fuel consumption of 40Cr steel connecting rods and BNNTs/Al connecting rods at varying power levels, thereby elucidating the energy-saving mechanism of material lightweighting. As demonstrated in

Figure 11b, the fuel consumption of both materials varies across the 5–25 kW power range. Evidence suggests that vehicles equipped with BNNTs/Al connecting rods exhibit significantly reduced fuel consumption in comparison to those with 40Cr steel connecting rods, thereby demonstrating a substantial reduction in energy expenditure. For instance, at 20 kW, under WLTC-equivalent operating conditions, the BNNTs/Al composite connecting rod exhibits approximately 5.8% lower fuel consumption than the conventional 40Cr steel connecting rod. The low fuel consumption of the BNNTs/Al connecting rod is primarily attributable to its superior specific strength and specific modulus. In the context of engine operation, the connecting rod is subjected to repetitive compressive stresses, with the inertia moment exerting a substantial influence on fuel consumption. BNNTs/Al possesses a density that is one-third that of 40Cr steel, thereby significantly reducing the weight of connecting rods while maintaining strength and stiffness. This reduction in weight decreases the inertia moment, thereby lowering the engine’s power loss. Furthermore, BNNTs provide multiscale reinforcement to the aluminium alloy, thereby enhancing the material’s adaptability to alternating loads. This enhancement contributes to enhanced combustion stability and thermal efficiency in the engine. It is noteworthy that as the power output increases, the discrepancy in fuel consumption between BNNTs/Al and 40Cr steel connecting rods becomes increasingly pronounced. This finding suggests that the energy-saving potential of the system is significant. This finding suggests that the energy-saving benefits of BNNTs/Al composites are more pronounced under high-power operating conditions. It has been demonstrated that, under conditions of elevated velocity and substantial load, there is a substantial augmentation in the inertial forces exerted by the connecting rod. The low density and high strength of BNNTs/Al material ensure effective reduction of vibration and impact, thus ensuring fuel economy.

The enhanced fuel economy not only contributes to a reduction in daily operating costs for vehicle owners but also signifies a substantial advancement in the implementation of energy conservation, emission reduction, and green development principles. To illustrate this point, consider the Toyota Carina model. Following the adoption of BNNTs/Al connecting rods, a 6.3% decrease in Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Cycle (WLTC) was observed in comparison to 40Cr steel connecting rods. Concurrently, there was a 5.8% reduction in carbon emissions per 100 km. The implementation of this technology across the entire model range has the potential to achieve significant environmental benefits, including the reduction of fuel consumption by tens of thousands of tons per year and a substantial decrease in carbon dioxide emissions by millions of tons. This contributes to the sustainable development of the automotive industry. The estimated fuel consumption and CO2 emission reductions represent potential savings under simplified assumptions, assuming widespread adoption of lightweight BNNTs/Al composite connecting rods and identical driving conditions. The calculations are based on average WLTC fuel consumption data, a simplified vehicle fleet model, and constant annual mileage, without considering variations in driving behavior, vehicle aging, or powertrain configuration.

In summary, BNNT-reinforced aluminium matrix composites, with their outstanding specific strength, specific stiffness, and damping properties, have the potential to significantly enhance the braking safety and fuel efficiency of automotive connecting rods. This provides new insights and material solutions for energy conservation, emission reduction, and lightweight design in automotive powertrain systems, driving the innovative development of green manufacturing technologies. However, the large-scale application of BNNTs/Al composites remains contingent on intensive research in cost control, process optimisation, and mass production. It is inevitable that, in the future, the collaborative innovation of industry, academia, research institutions, and end-users will accelerate the pace of BNNTs’ automotive applications. This will contribute to the development of a green, efficient, and sustainable automotive industrial system, by providing wisdom and strength.

In this study, fatigue testing (such as S–N curve measurement) was not conducted because the primary objective was to establish the feasibility of BNNT-reinforced aluminium composites for connecting rod applications and to evaluate their static mechanical behaviour. Future work will focus on fatigue performance, including high-cycle and low-cycle fatigue tests, to more comprehensively assess the long-term service reliability of BNNTs/Al components. Mechanical properties at elevated temperatures above room temperature were not included in the present investigation. The current work concentrated on the interfacial behaviour, wetting characteristics, and static mechanical properties as a preliminary assessment. In future studies, tensile and compressive tests at temperatures closer to practical engine operating conditions (150–350 °C) will be conducted to further validate the thermal-mechanical stability of BNNTs/Al composites during real service.