Effect of Sodium Sulfate on Fracture Properties and Microstructure of High-Volume Slag-Cement Mortar

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Mixture Design and Preparation Process

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Compressive Strength

2.3.2. Fracture Properties

2.3.3. XRD

2.3.4. FTIR

2.3.5. SEM-EDS

2.3.6. Environmental Impact Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Compressive Strength

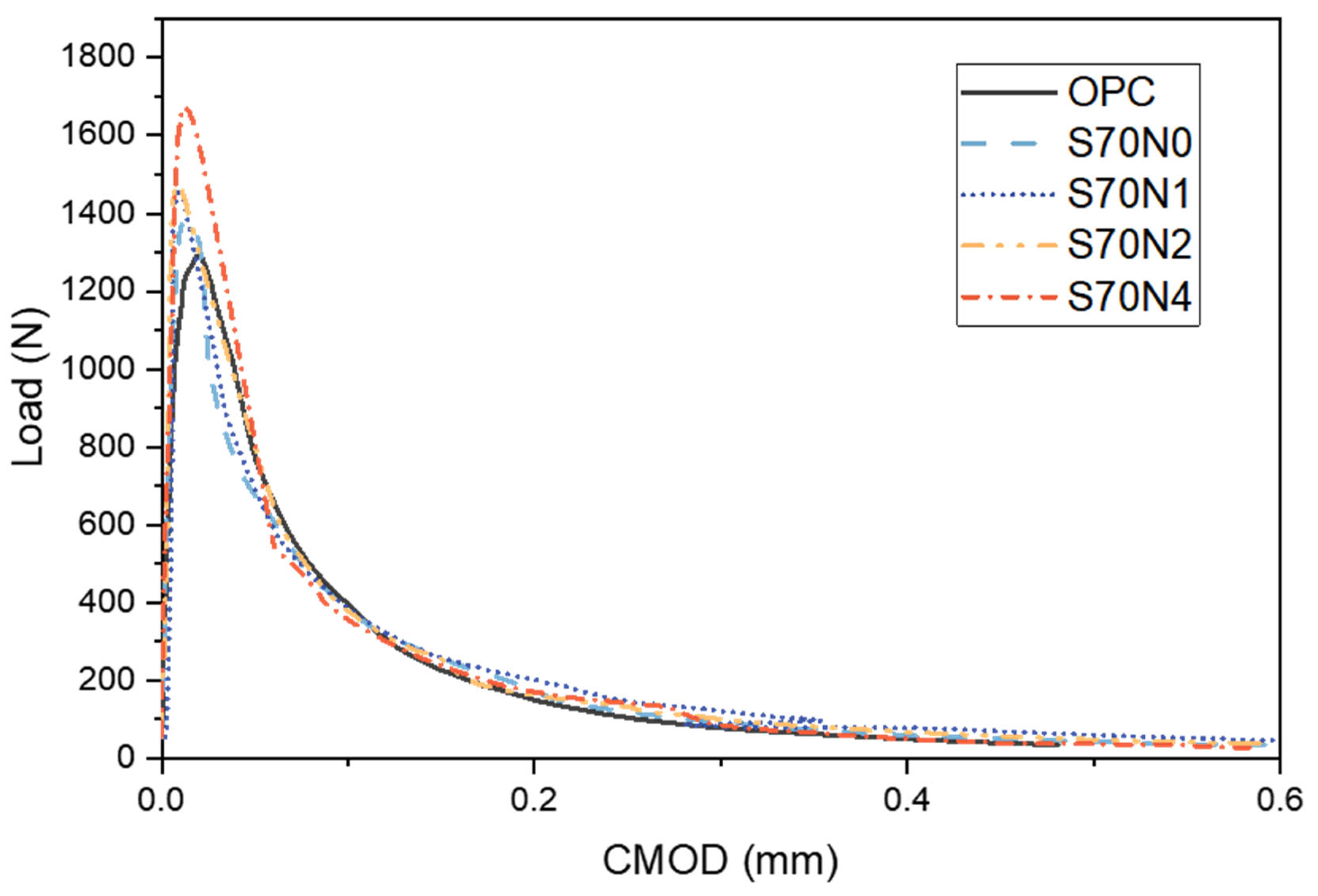

3.2. Fracture Properties

3.2.1. Fracture Toughness

3.2.2. Fracture Energy

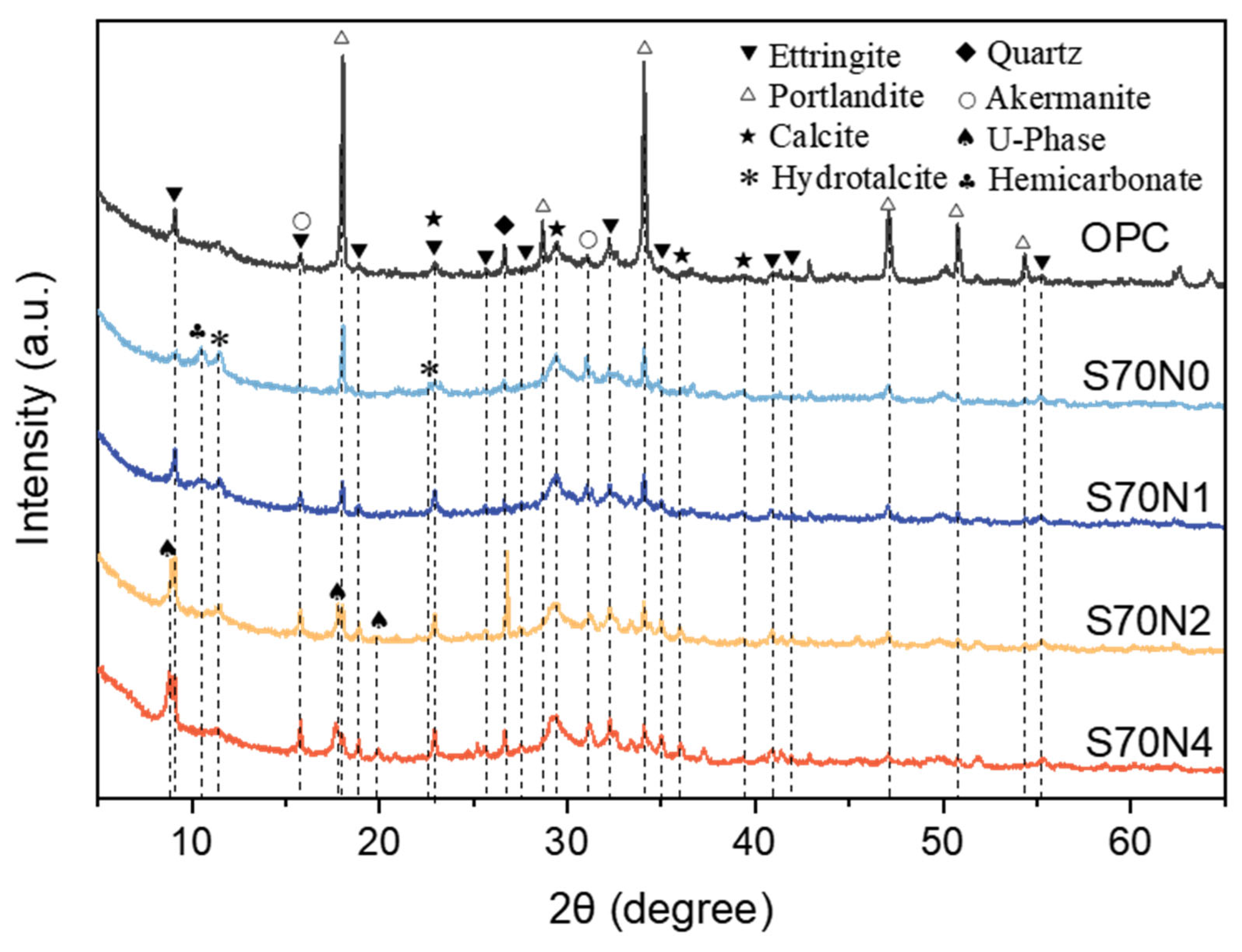

3.3. XRD Analysis

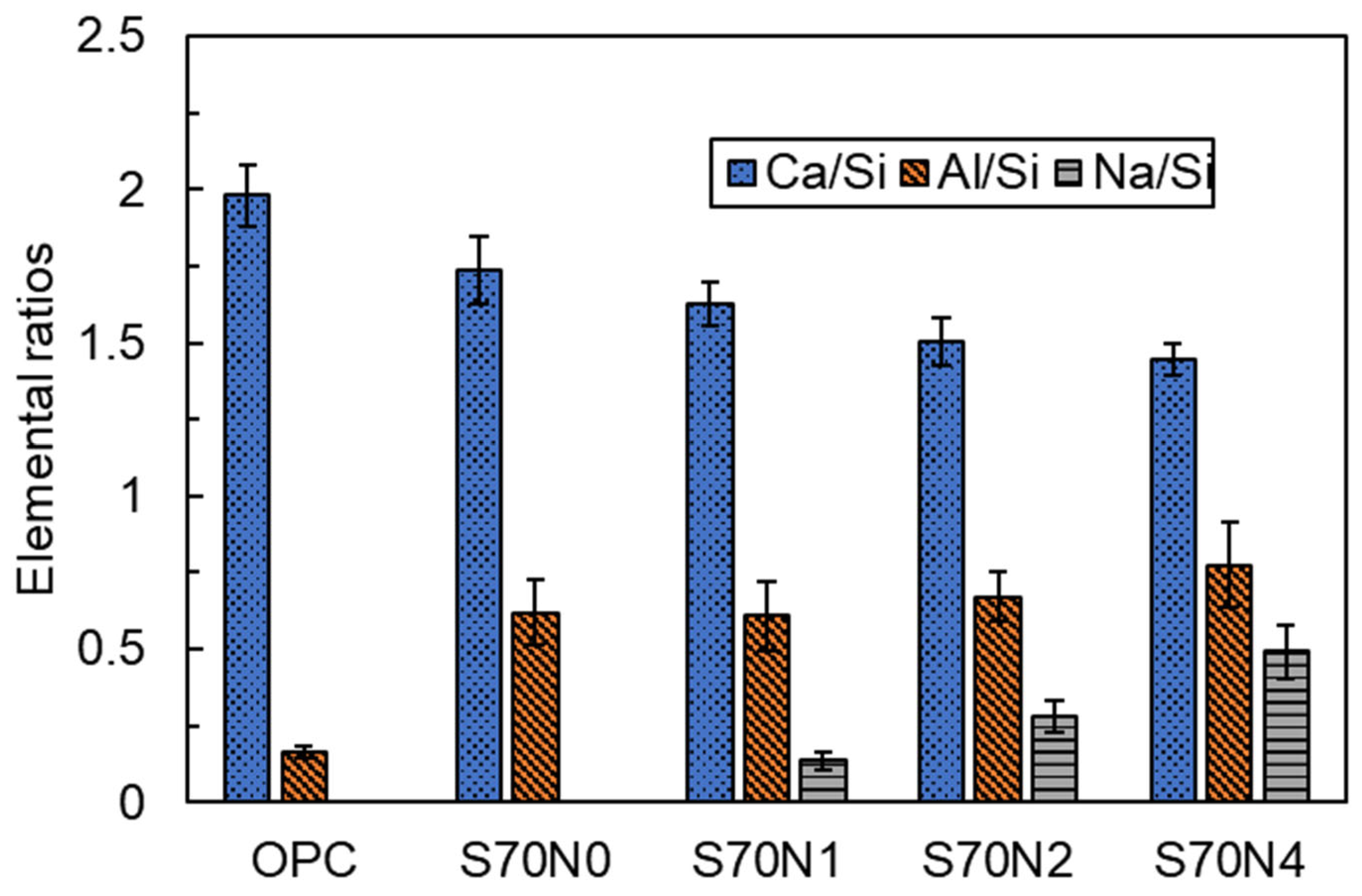

3.4. SEM and EDS Analysis

3.5. FTIR Analysis

3.6. Environmental Impact Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- 1.

- The compressive strength of the slag-cement blends was lower than that of OPC at early ages but eventually achieved comparable or higher strength by 28 days, owing to the formation of a denser binder phase. The Na2SO4 activation of HVSCM significantly boosted early-age strength. However, it resulted in a reduction in the 28 day compressive strength compared to the non-activated slag mixture, which is attributed to a decreased later-age hydration degree.

- 2.

- Slag-cement blends exhibited higher peak loads and fracture toughness compared to OPC mortars. The generation of more polymerized C-(A)-S-H and denser microstructure contributed to the enhancement of the fracture toughness of the S70N0 samples. The fracture energy of slag-cement blends was also superior to that of OPC, but it remained largely unaffected by the addition of Na2SO4.

- 3.

- Na2SO4 activation increased Al/Si and Na/Si ratios in C-(A)-S-H gel and promoted the formation of ettringite in the slag-cement blends. The introduced sodium ions reduced the polymerization degree of C-(A)-S-H. Despite this depolymerization, the fracture toughness of Na2SO4-activated blends increased. This is attributed to the enhanced cohesion between C-(A)-S-H globules, resulting from stronger electrostatic attraction induced by the sodium ions, which improved the resistance to crack initiation and propagation.

- 4.

- Environmental analysis showed that both Na2SO4-activated and non-activated slag-cement blends can significantly reduce embodied energy and CO2 emissions compared to OPC, indicating superior sustainability. The addition of Na2SO4 led to a slight increase in the overall environmental impact.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, Z.; Zhu, X.; Wang, J.; Mu, M.; Wang, Y. Comparison of CO2 emissions from OPC and recycled cement production. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 211, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Zhou, J.; Yang, F.; Lan, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Xu, M.; Li, H.; Sanjayan, J.G. Analysis of theoretical carbon dioxide emissions from cement production: Methodology and application. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 334, 130270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibsted, J.; Snellings, R. Reactivity of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) in cement blends. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 124, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xiao, R.; Bai, Y.; Huang, B.; Ma, Y. Influence of waste glass powder as a supplementary cementitious material (SCM) on physical and mechanical properties of cement paste under high temperatures. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 340, 130778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Jones, A.M.; Bligh, M.W.; Holt, C.; Keyte, L.M.; Moghaddam, F.; Foster, S.J.; Waite, T.D. Mechanisms of enhancement in early hydration by sodium sulfate in a slag-cement blend—Insights from pore solution chemistry. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 135, 106110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, R.; Zhu, C.; Meng, Q. The effect of fly ash and silica fume on mechanical properties and durability of coral aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 185, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Bligh, M.W.; Shikhov, I.; Jones, A.M.; Holt, C.; Keyte, L.M.; Moghaddam, F.; Arns, C.H.; Foster, S.J.; Waite, T.D. A microstructural investigation of a Na2SO4 activated cement-slag blend. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 150, 106609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.H.P.; Nehring, V.; De paiva, F.F.G.; Tamashiro, J.R.; Galvín, A.P.; López-Uceda, A.; Kinoshita, A. Use of blast furnace slag in cementitious materials for pavements-Systematic literature review and eco-efficiency. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 33, 101030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbay, E.; Erdemir, M.; Durmuş, H.İ. Utilization and efficiency of ground granulated blast furnace slag on concrete properties—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 105, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Shen, Z.; Si, R.; Polaczyk, P.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; Huang, B. Alkali-activated slag (AAS) and OPC-based composites containing crumb rubber aggregate: Physico-mechanical properties, durability and oxidation of rubber upon NaOH treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 132896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneyisi, E.; Gesoğlu, M. A study on durability properties of high-performance concretes incorporating high replacement levels of slag. Mater. Struct. 2008, 41, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Qian, J. High performance cementing materials from industrial slags—A review, Resources. Conserv. Recycl. 2000, 29, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.; Sánchez, I.; Climent, M. Durability related transport properties of OPC and slag cement mortars hardened under different environmental conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 27, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Gao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Guo, Z.; Luo, X.; Chen, G. Promoting utilization rate of ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS): Incorporation of nanosilica to improve the properties of blended cement containing high volume GGBS. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 332, 130096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Martinez, E.; Gomez-Zamorano, L.; Escalante-Garcia, J. Portland cement-blast furnace slag mortars activated using waterglass:—Part 1: Effect of slag replacement and alkali concentration. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 37, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.; Bai, Y.; Basheer, P.; Milestone, N.; Collier, N. Hydration and properties of sodium sulfate activated slag. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 37, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tan, H.; Bao, M.; Liu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, P. Low carbon cementitious materials: Sodium sulfate activated ultra-fine slag/fly ash blends at ambient temperature. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Shi, C.; Li, N. Fracture properties of slag/fly ash-based geopolymer concrete cured in ambient temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 190, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yao, Y. Measurement and correlation of ductility and compressive strength for engineered cementitious composites (ECC) produced by binary and ternary systems of binder materials: Fly ash, slag, silica fume and cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 68, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbay, E.; Karahan, O.; Lachemi, M.; Hossain, K.M.; Atis, C.D. Dual effectiveness of freezing–thawing and sulfate attack on high-volume slag-incorporated ECC. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 45, 1384–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C109/C109M (2016); Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars (Using 2-in. or [50-mm] Cube Specimens). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.astm.org/ (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Xu, S.; Reinhardt, H.W. Determination of double-K criterion for crack propagation in quasi-brittle fracture, Part I: Experimental investigation of crack propagation. Int. J. Fract. 1999, 98, 111–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Reinhardt, H.W. Determination of double-K criterion for crack propagation in quasi-brittle fracture, Part II: Analytical evaluating and practical measuring methods for three-point bending notched beams. Int. J. Fract. 1999, 98, 151–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhu, H.; Lu, F. Fracture properties of slag-based alkali-activated seawater coral aggregate concrete. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2021, 115, 103071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, S.; He, Z. Mechanical and fracture properties of geopolymer concrete with basalt fiber using digital image correlation. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2021, 112, 102909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Ghiassi, B.; Yin, S.; Ye, G. Fracture properties and microstructure formation of hardened alkali-activated slag/fly ash pastes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 144, 106447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Wu, Z.; Khayat, K.H.; Wei, J.; Dong, B.; Xing, F.; Zhang, J. Design, dynamic performance and ecological efficiency of fiber-reinforced mortars with different binder systems: Ordinary Portland cement, limestone calcined clay cement and alkali-activated slag. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, X.; Zhou, J.; Shi, Y.; Umar, H.A.; Long, G.; Xie, Y. Development of an eco-friendly ultra-high performance concrete based on waste basalt powder for Sichuan-Tibet Railway. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, B.; He, Q. Strength, microstructure, efflorescence behavior and environmental impacts of waste glass geopolymers cured at ambient temperature. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Sarker, P.K.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Saha, A.K. Soundness and compressive strength of Portland cement blended with ground granulated ferronickel slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 140, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, H.; Yardımcı, M.Y.; Yiğiter, H.; Aydın, S.; Türkel, S. Mechanical properties of reactive powder concrete containing high volumes of ground granulated blast furnace slag. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, V.H.J.M.; Pontin, D.; Ponzi, G.G.D.; E Stepanha, A.S.D.G.; Martel, R.B.; Schütz, M.K.; Einloft, S.M.O.; Vecchia, F.D. Application of Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) coupled with multivariate regression for calcium carbonate (CaCO3) quantification in cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 313, 125413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.K.; Jeon, S.; Lee, B.Y.; Kim, H. Use of circulating fluidized bed combustion bottom ash as a secondary activator in high-volume slag cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 234, 117240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, O.M.; Fraj, A.B.; Bouasker, M.; Khouchaf, L.; Khelidj, A. Microstructural investigation of slag-blended UHPC: The effects of slag content and chemical/thermal activation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 292, 123455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Han, L.; Poon, C.S. Deep insight into mechanical behavior and microstructure mechanism of quicklime-activated ground granulated blast-furnace slag pastes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 134, 104767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; He, Y.; Lu, L.; Hu, S. The effect of activators on the dissolution characteristics and occurrence state of aluminum of alkali-activated metakaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 235, 117451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yao, X.; Wang, C.; Geng, C.; Yang, T. Properties and microstructure of eco-friendly alkali-activated slag cements under hydrothermal conditions relevant to well cementing applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 318, 125973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tan, H.; He, X.; Yang, W.; Deng, X. Utilization of carbide slag-granulated blast furnace slag system by wet grinding as low carbon cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 249, 118763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Geng, G.; Du, H.; Pang, S.D. The role of age on carbon sequestration and strength development in blended cement mixes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 133, 104644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y.; She, W.; Liu, G.; Yang, Y.; Rong, Z.; Sun, W. The influence of chemical admixtures on the strength and hydration behavior of lime-based composite cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 103, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Dai, J.; Shi, C. Fracture properties of alkali-activated slag and ordinary Portland cement concrete and mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 165, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Königsberger, M.; Carette, J. Validated hydration model for slag-blended cement based on calorimetry measurements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 128, 105950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallet, V.; Pedersen, M.T.; Lothenbach, B.; Winnefeld, F.; De Belie, N.; Pontikes, Y. Hydration of blended cement with high volume iron-rich slag from non-ferrous metallurgy. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 151, 106624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; White, C.E. Modeling of aqueous species interaction energies prior to nucleation in cement-based gel systems. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 139, 106266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodeiro, I.G.; Macphee, D.; Palomo, A.; Fernández-jiménez, A. Effect of alkalis on fresh C–S–H gels. FTIR analysis. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009, 39, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapeluszna, E.; Kotwica, Ł.; Różycka, A.; Gołek, Ł. Incorporation of Al in C-A-S-H gels with various Ca/Si and Al/Si ratio: Microstructural and structural characteristics with DTA/TG, XRD, FTIR and TEM analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 155, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, K.; Guan, X. Properties of sulfoaluminate cement-based grouting materials modified with LiAl-layered double hydroxides in the presence of PCE superplasticizer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 226, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trezza, M.; Rahhal, V.F. Self-activation of slag-cements with glass waste powder. Mater. Construcción 2019, 69, e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lee, Y.; Cho, H.; Lee, H.; Lim, S. Improvement in carbonation resistance of portland cement mortar incorporating γ-dicalcium silicate. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddei, P.; Tinti, A.; Gandolfi, M.G.; Rossi, P.; Prati, C. Vibrational study on the bioactivity of Portland cement-based materials for endodontic use. J. Mol. Struct. 2009, 924, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.R.; Qian, L.; Fang, Y.; Wang, A.; Dai, J. A multiscale study on gel composition of hybrid alkali-activated materials partially utilizing air pollution control residue as an activator. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 136, 104856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lothenbach, B.; Jansen, D.; Yan, Y.; Schreiner, J. Solubility and characterization of synthesized 11 Å Al-tobermorite. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 159, 106871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Meng, F.; Shi, H. Microstructure and characterization of hydrothermal synthesis of Al-substituted tobermorite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 133, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.; Yan, Y.; Lothenbach, B. Effective cation exchange capacity of calcium silicate hydrates (C-S-H). Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 143, 106393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Özçelik, V.O.; Skibsted, J.; White, C.E. Nanoscale Ordering and Depolymerization of Calcium Silicate Hydrates in the Presence of Alkalis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 24873–24883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yin, J.; Yuan, Q.; Huang, L.; Li, J. Greener strain-hardening cementitious composites (SHCC) with a novel alkali-activated cement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 134, 104735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Farzadnia, N.; Shi, C. Microstructural changes in alkali-activated slag mortars induced by accelerated carbonation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 100, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Z. Carbonation induced phase evolution in alkali-activated slag/fly ash cements: The effect of silicate modulus of activators. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 223, 566–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevová, E.; Vaculikova, L.; Kozusnikova, A.; Ritz, M.; Simha Martynková, G. Thermal expansion behaviour of granites. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 123, 1555–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Z. Effect of Na2O concentration and water/binder ratio on carbonation of alkali-activated slag/fly ash cements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senvaitiene, J.; Smirnova, J.; Beganskiene, A.; Kareiva, A. XRD and FTIR Characterisation of Lead Oxide-Based Pigments and Glazes. Acta Chim. Slov. 2007, 54, 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-döhl, F.M.; Schulenberg, D.; Tralow, F.; Neubauer, J.; Wolf, J.J.; Ectors, D. Quantitative analysis of the strength generating C-S-H-phase in concrete by IR-spectroscopy. Acta Polytech. CTU Proc. 2022, 33, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Thom, N. Effects of alkali dosage and silicate modulus on autogenous shrinkage of alkali-activated slag cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 141, 106322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Ding, Q.; Sun, D. Insight into the strengthening mechanism of the al-induced cross-linked calcium aluminosilicate hydrate gel: A molecular dynamics study. Front. Mater. 2021, 7, 611568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y.; She, W.; Liu, G.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sun, W. Effects of sodium sulfate on the hydration and properties of lime-based low carbon cementitious materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CKulasuriya; Vimonsatit, V.; Dias, W. Performance based energy, ecological and financial costs of a sustainable alternative cement. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, M.M.; Brooks, J.; Kabir, S.; Rivard, P. Influence of supplementary cementitious materials on engineering properties of high strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 2639–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, B.; Matschei, T.; Scrivener, K. Impact of NaOH and Na2SO4 on the kinetics and microstructural development of white cement hydration. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 108, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Wu, C.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Lu, Z.; Wang, P.; Li, J.; Ding, Q. Insights on the molecular structure evolution for tricalcium silicate and slag composite: From 29Si and 27Al NMR to molecular dynamics. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 202, 108401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García lodeiro, I.; Fernández-jimenez, A.; Palomo, A.; Macphee, D. Effect on fresh C-S-H gels of the simultaneous addition of alkali and aluminium. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zheng, K.; Chen, W.; Chen, L.; Zhou, J.; Mi, T. The correlation between Al incorporation and alkali fixation by calcium aluminosilicate hydrate: Observations from hydrated C3S blended with and without metakaolin. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 172, 107249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Yang, S. Mechanical properties of C-S-H globules and interfaces by molecular dynamics simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 176, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaphary, Y.L.; Lau, D.; Sanchez, F.; Poon, C.S. Effects of sodium/calcium cation exchange on the mechanical properties of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H). Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 243, 118283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPlassard; Lesniewska, E.; Pochard, I.; Nonat, A. Nanoscale experimental investigation of particle interactions at the origin of the cohesion of cement. Langmuir 2005, 21, 7263–7270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | MgO | SO3 | TiO2 | Na2O | MnO | K2O | Fe2O3 | LOI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPC | 52.88 | 22.71 | 8.43 | 4.12 | 3.85 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.93 | 3.01 | 3.16 |

| GGBS | 39.74 | 27.88 | 17.42 | 8.39 | 2.38 | 1.38 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.3 | 1.4 |

| Mix ID | OPC (%) | Slag (%) | Na2SO4 (Weight% to Binder) | Water/Binder Ratio | Sand/Binder Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPC | 100 | - | - | 0.45 | 2.25 |

| S70N0 | 30 | 70 | - | 0.45 | 2.25 |

| S70N1 | 30 | 70 | 2.29 | 0.45 | 2.25 |

| S70N2 | 30 | 70 | 4.58 | 0.45 | 2.25 |

| S70N4 | 30 | 70 | 9.16 | 0.45 | 2.25 |

| Component | OPC | S70N0 | S70N1 | S70N2 | S70N4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative area of Q1 | 5.61 | 3.36 | 3.07 | 3.29 | 3.89 |

| Relative area of Q2 | 78.00 | 84.14 | 34.82 | 27.71 | 29.63 |

| Q2/Q1 area ratio | 13.90 | 25.07 | 11.32 | 8.43 | 7.62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Si, R.; Han, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H. Effect of Sodium Sulfate on Fracture Properties and Microstructure of High-Volume Slag-Cement Mortar. Materials 2026, 19, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010043

Si R, Han X, Zhang Y, Zeng H. Effect of Sodium Sulfate on Fracture Properties and Microstructure of High-Volume Slag-Cement Mortar. Materials. 2026; 19(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleSi, Ruizhe, Xiangyu Han, Yue Zhang, and Haonan Zeng. 2026. "Effect of Sodium Sulfate on Fracture Properties and Microstructure of High-Volume Slag-Cement Mortar" Materials 19, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010043

APA StyleSi, R., Han, X., Zhang, Y., & Zeng, H. (2026). Effect of Sodium Sulfate on Fracture Properties and Microstructure of High-Volume Slag-Cement Mortar. Materials, 19(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010043