Fundamentals of Cubic Phase Synthesis in PbF2–EuF3 System

Highlights

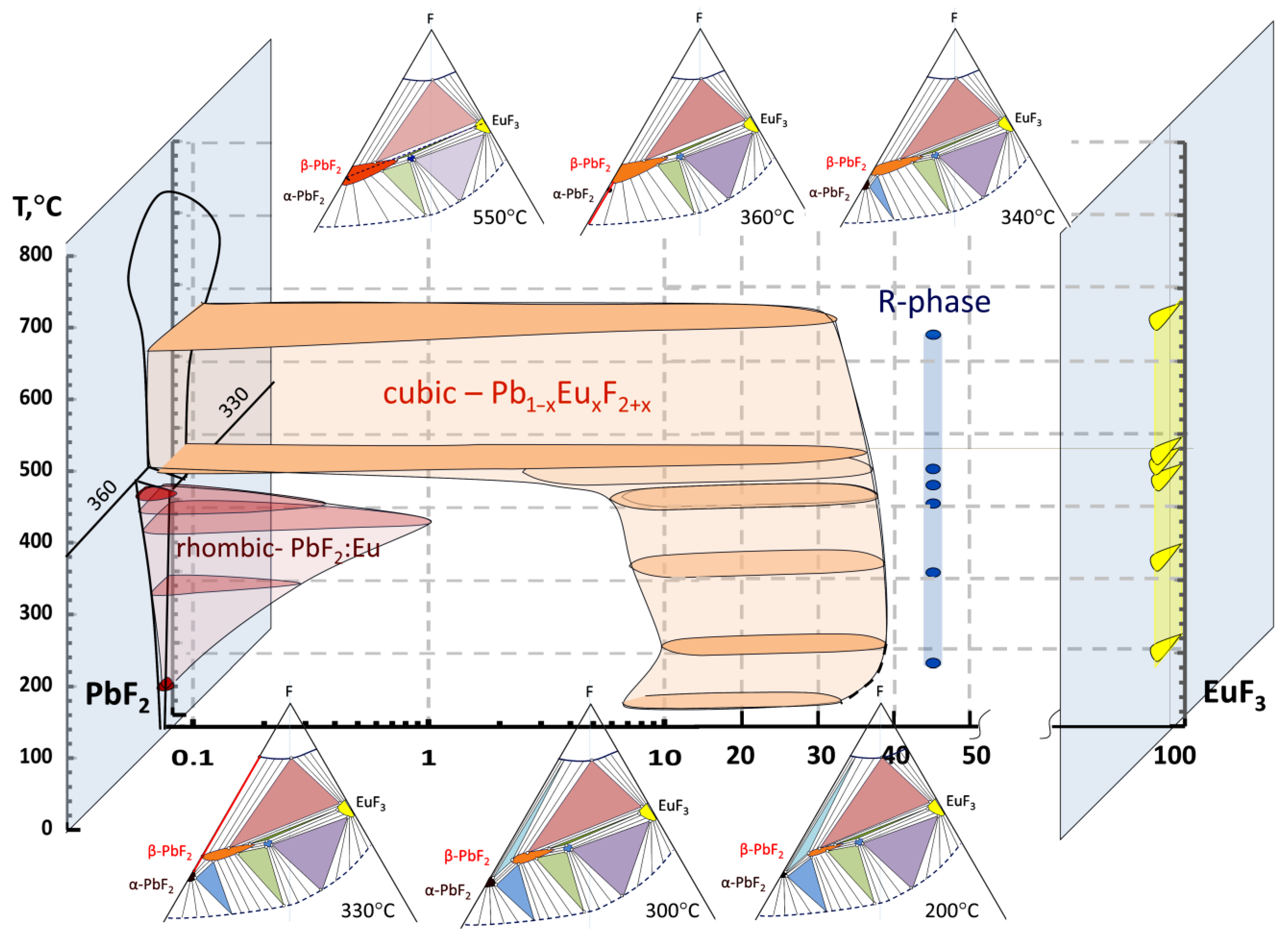

- A high-purity cubic phase could be synthesized in the 0–37 mol% EuF3 composition range in a quasi-binary PbF2-EuF3 system.

- The ordered rhombohedral R-phase exists in the concentration range from 37–39 to 43–44 mol% EuF3 in the quasi-binary PbF2-EuF3 system.

- Isothermal cross-sections of T-X-Y projection of ternary Pb-Eu-F diagram in the 50–550 °C temperature range are reconstructed.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

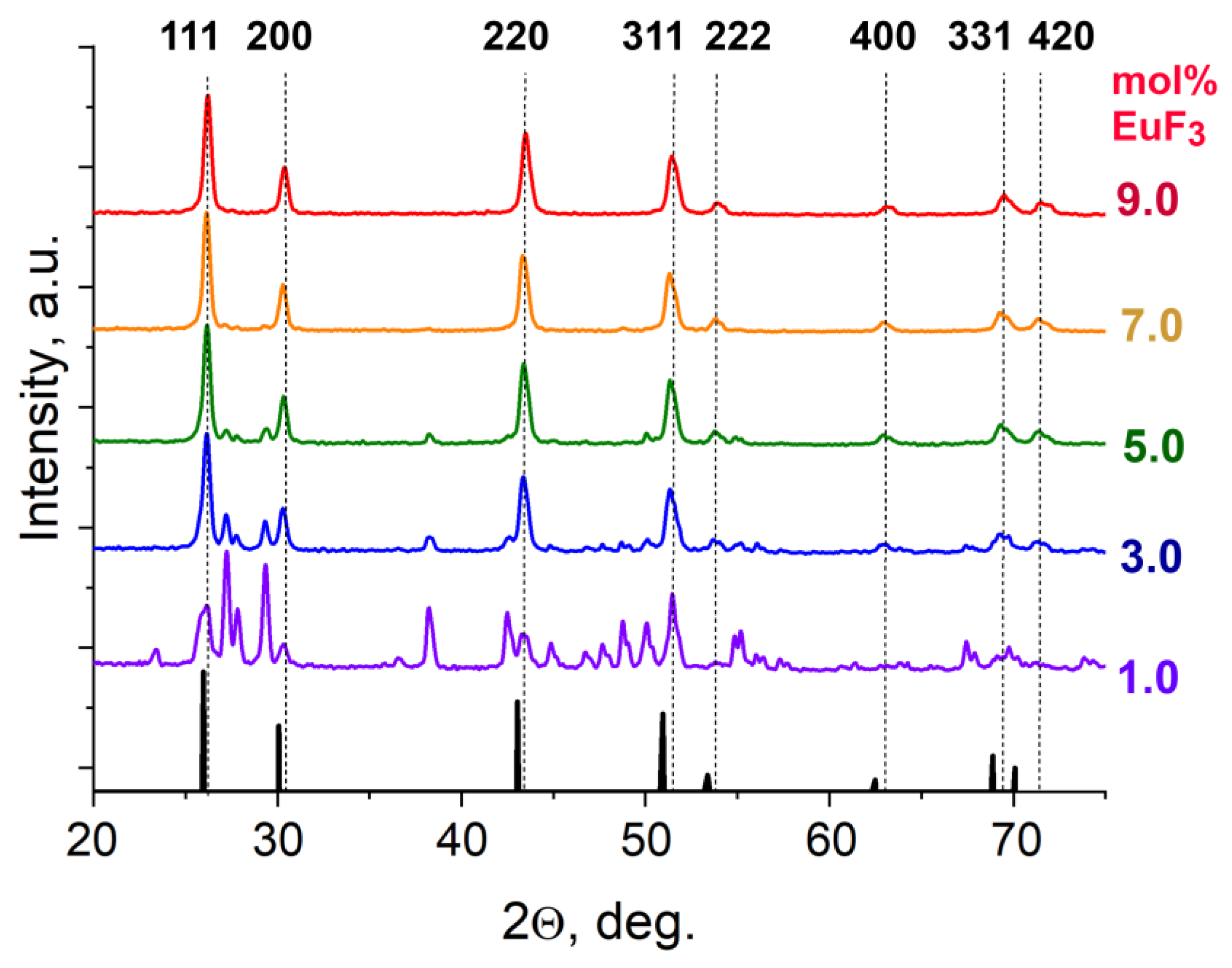

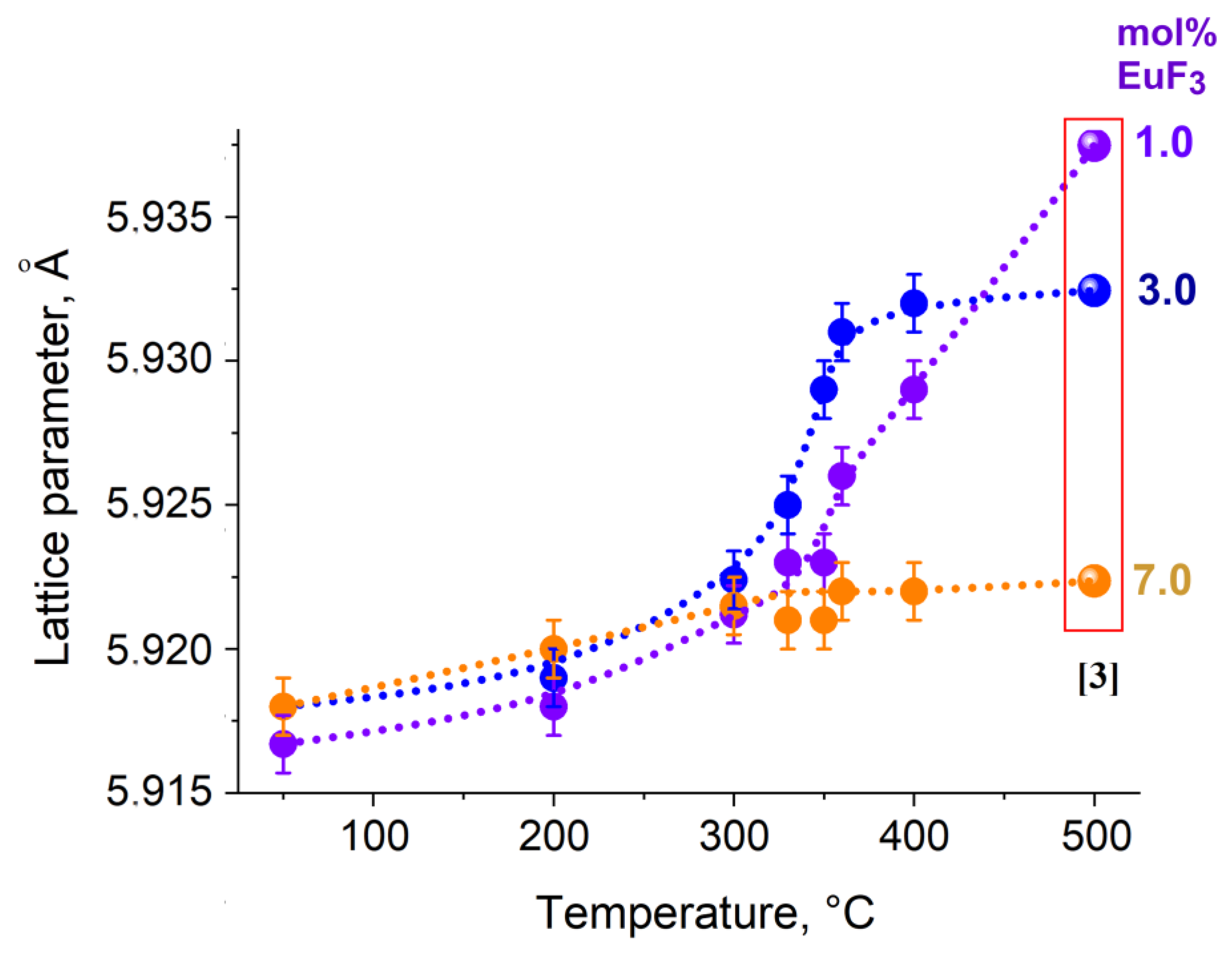

3.1. Position of the Solvus Line on the PbF2-EuF3 Diagram

3.2. Determining the Existence Region of the Rhombohedral R-Phase in the PbF2-EuF3 System

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ntoupis, V.; Linardatos, D.; Saatsakis, G.; Kalyvas, N.; Bakas, A.; Fountos, G.; Kandarakis, I.; Michail, C.; Valais, I. Response of Lead Fluoride (PbF2) Crystal under X-Ray and Gamma Ray Radiation. Photonics 2023, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PbF2—Lead Fluoride Scintillator Crystal|Advatech UK. Available online: https://www.advatech-uk.co.uk/pbf2.html (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- A Roadmap for Sole Cherenkov Radiators with SiPMs in TOF-PET—IOPscience. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1361-6560/ac212a (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Cantone, C.; Carsi, S.; Ceravolo, S.; Di Meco, E.; Diociaiuti, E.; Frank, I.; Kholodenko, S.; Martellotti, S.; Mirra, M.; Monti-Guarnieri, P.; et al. Beam Test, Simulation, and Performance Evaluation of PbF2 and PWO-UF Crystals with SiPM Readout for a Semi-Homogeneous Calorimeter Prototype with Longitudinal Segmentation. Front. Phys. 2023, 11, 1223183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Mo, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Ge, H.; Han, D.; Hao, A.; Chai, B.; She, J. Screen Printing of Upconversion NaYF4:Yb3+/Eu3+ with Li+ Doped for Anti-Counterfeiting Application. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2020, 18, 110501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Pun, E.Y.B.; Lin, H. Fluorescence Regulation Derived from Eu3+ in Miscible-Order Fluoride-Phosphate Blocky Phosphor. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 435705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasa, P.; Ran, F.; Basavapoornima, C.; Depuru, S.R.; Jayasankar, C.K. Optical Characteristics of (Eu3+,Nd3+) Co-Doped Leadfluorosilicate Glasses for Enhanced Photonic Device Applications. J. Lumin. 2020, 223, 117210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosawa, S.; Yokota, Y.; Yanagida, T.; Yoshikawa, A. Optical and Scintillation Property of Ce, Ho and Eu-Doped PbF2. Radiat. Meas. 2013, 55, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchinskaya, I.I.; Fedorov, P.P. Lead Difluoride and Related Systems. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2004, 73, 371–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.K.; Patwe, S.J.; Achary, S.N.; Mallia, M.B. Phase Relation Studies in Pb1−xM′xF2+x Systems (0.0 ≤ x ≤ 1.0; M′ = Nd3+, Eu3+ and Er3+). J. Solid State Chem. 2004, 177, 1746–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, O.B.; Mayakova, M.N.; Smirnov, V.A.; Runina, K.I.; Avetisov, R.I.; Avetissov, I.C. Luminescent Properties of Solid Solutions in the PbF2-EuF3 and PbF2–ErF3 Systems. J. Lumin. 2021, 238, 118262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevostjanova, T.S.; Khomyakov, A.V.; Mayakova, M.N.; Voronov, V.V.; Petrova, O.B. Luminescent Properties of Solid Solutions in the PbF2–Euf3 System and Lead Fluoroborate Glass Ceramics Doped with Eu3+ Ions. Opt. Spectrosc. 2017, 123, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savikin, A.P.; Egorov, A.S.; Budruev, A.V.; Perunin, I.Y.; Grishin, I.A. Visualization of 1.908-Μm Radiation of a Tm:YLF Laser Using PbF2-Based Ceramics Doped with Ho3+ Ions. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2016, 42, 1083–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Chen, Q.; Niu, X.; Zhang, P.; Tan, H.; Ma, F.; Li, Z.; Zhu, S.; Hang, Y.; Yang, Q.; et al. Energy Transfer and Cross-Relaxation Induced Efficient 2.78 Μm Emission in Er3+/Tm3+: PbF2 Mid-Infrared Laser Crystal. Crystals 2021, 11, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Su, Z.; Xu, J.; Xin, K.; Hang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yin, H.; Li, Z.; et al. Efficiently Strengthen and Broaden 3 Μm Fluorescence in PbF2 Crystal by Er3+/Ho3+ as Co-Luminescence Centers and Pr3+ Deactivation. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 811, 152027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Yin, H.; Zhu, S.; Li, Z.; Hang, Y.; Chen, Z. Sensitization and Deactivation Effects of Nd3+ on the Er3+: 27 Μm Emission in PbF2 Crystal. Opt. Mater. Express 2019, 9, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhang, P.; Niu, X.; Liao, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, S.; Hang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Yin, H.; Li, Z.; et al. Ultra-Broadband and Enhanced near-Infrared Emission in Bi/Er Co-Doped PbF2 Laser Crystal. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 895, 162704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, N.I.; Ivanovskaya, N.A.; Buchinskaya, I.I. Ionic Conductivity of Cold Pressed Nanoceramics Pr0.9Pb0.1F2.9 Obtained by Mechanosynthesis of Components. Phys. Solid State 2023, 65, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, B.P. The Rare Earth Trifluorides: The High Temperature Chemistry of the Rare Earth Trifluorides. Part 2. Introduction to Materials Science of Multicomponent Metal Fluoride Crystals; Arxius de les seccions de ciències; Institut d’Estudis Catalans: Barcelona, Spain, 2001; ISBN 84-7283-610-X. [Google Scholar]

- Achary, S.N.; Patwe, S.J.; Tyagi, A.K. Powder XRD Study of Ba4Eu3F17: A New Anion Rich Fluorite Related Mixed Fluoride. Powder Diffr. 2002, 17, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombrovski, E.N.; Serov, T.V.; Abakumov, A.M.; Ardashnikova, E.I.; Dolgikh, V.A.; Van Tendeloo, G. The Structural Investigation of Ba4Bi3F17. J. Solid State Chem. 2004, 177, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwe, S.; Achary, S.; Tyagi, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Ba1−xErxF2+x (0.00 ≤ x ≤ 1.00). Mater. Res. Bull. 2002, 37, 2243–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwe, S.J.; Achary, S.N.; Tyagi, A.K. Synthesis and Characterization of Y1-XPb2+1.5xF7 (−1.33 ≤ x ≤ 1.0). Mater. Res. Bull. 2001, 36, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiko, P.; Rytz, D.; Schwung, S.; Pues, P.; Jüstel, T.; Doualan, J.-L.; Camy, P. Watt-Level Europium Laser at 703 Nm. Opt. Lett. 2021, 46, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.; Barnes, H. Sphalerite-Wurtzite Equilibria and Stoichiometry. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1972, 36, 1275–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayakova, M.N.; Voronov, V.V.; Iskhakova, L.D.; Kuznetsov, S.V.; Fedorov, P.P. Low-Temperature Phase Formation in the BaF2-CeF3 System. J. Fluor. Chem. 2016, 187, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, D.N.; Sorokin, N.I.; Chernov, S.P.; Sobolev, B.P. Growth of MgF2 Optical Crystals and Their Ionic Conductivity in the As-Grown State and after Partial Pyrohydrolysis. Crystallogr. Rep. 2014, 59, 928–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaguma, Y.; Ueda, K.; Katsumata, T.; Noda, Y. Low-Temperature Formation of Pb2OF2 with O/F Anion Ordering by Solid State Reaction. J. Solid State Chem. 2019, 277, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strekalov, P.V.; Mayakova, M.N.; Runina, K.I.; Petrova, O.B. Organic Phosphor and Lead Fluoride Based Luminescent Hybrids. Tsvetnye Met. 2021, 10, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borik, M.A.; Gerasimov, M.V.; Kulebyakin, A.V.; Larina, N.A.; Lomonova, E.E.; Milovich, F.O.; Myzina, V.A.; Ryabochkina, P.A.; Sidorova, N.V.; Tabachkova, N.Y. Structure and Phase Transformations in Scandia, Yttria, Ytterbia and Ceria-Doped Zirconia-Based Solid Solutions during Directional Melt Crystallization. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 844, 156040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystallography Open Database. Available online: https://www.crystallography.net/cod/1530196.html (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Sorokin, N.I. Molar Volume Correlation between Nonstoichiometric M1 − xRxF2 + x (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5) and Ordered MmRnF2m + 3n (m/n = 8/6, 9/5) Phases in Systems MF2–RF3 (M = Ca, Sr, Ba, Pb; and R = Rare-Earth Elements). Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 64, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A. The Raman Effect: Applications; M. Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Bazhenov, A.V.; Smirnova, I.S.; Fursova, T.N.; Maksimuk, M.Y.; Kulakov, A.B.; Bdikin, I.K. Optical Phonon Spectra of PbF2 Single Crystals. Phys. Solid State 2000, 42, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, K. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangadurai, P.; Ramasamy, S.; Kesavamoorthy, R. Raman Studies in Nanocrystalline Lead (II) Fluoride. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2005, 17, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, S.V.; Nizamutdinov, A.S.; Madirov, E.I.; Voronov, V.V.; Tsoy, K.S.; Khadiev, A.R.; Yapryntsev, A.D.; Ivanov, V.K.; Kharintsev, S.S.; Semashko, V.V. Near Infrared Down-Conversion Luminescence of Ba4Y3F17:Yb3+:Eu3+ Nanoparticles under Ultraviolet Excitation. Nanosyst. Phys. Chem. Math. 2020, 11, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishio, K.; Shimoyama, J.; Hasegawa, T.; Kitazawa, K.; Fueki, K. Determination of Oxygen Nonstoichiometry in a High-T c Superconductor Ba2YCu3O7-δ. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1987, 26, L1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zykova, S.; Runina, K.; Mayakova, M.; Berezina, M.; Petrova, O.; Avetisov, R.; Avetissov, I. Fundamentals of Cubic Phase Synthesis in PbF2–EuF3 System. Materials 2026, 19, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010195

Zykova S, Runina K, Mayakova M, Berezina M, Petrova O, Avetisov R, Avetissov I. Fundamentals of Cubic Phase Synthesis in PbF2–EuF3 System. Materials. 2026; 19(1):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010195

Chicago/Turabian StyleZykova, Sofia, Kristina Runina, Mariya Mayakova, Maria Berezina, Olga Petrova, Roman Avetisov, and Igor Avetissov. 2026. "Fundamentals of Cubic Phase Synthesis in PbF2–EuF3 System" Materials 19, no. 1: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010195

APA StyleZykova, S., Runina, K., Mayakova, M., Berezina, M., Petrova, O., Avetisov, R., & Avetissov, I. (2026). Fundamentals of Cubic Phase Synthesis in PbF2–EuF3 System. Materials, 19(1), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010195